As delegates prepare to meet for a second negotiation on a global treaty to curtail plastic pollution, a pair of new reports from the United Nations Environment Program offers a roadmap of potential solutions to cut plastic waste by 80 percent—but also reveal the complexity of the problem.

Another recent United Nations action blocked what the chemical and plastic industries sometimes call “chemical recycling” from being fully incorporated into important global technical guidelines for managing plastic waste, potentially minimizing the role of such processes in any future global plastics treaty.

Together, this flurry of activity precedes the next round of U.N. plastics treaty talks to be held in Paris May 29 to June 2 as part of fast-tracked negotiations scheduled to wrap up by the end of next year. Last year, 175 nations agreed to find a way to stop future plastic production from choking ocean and land ecosystems and to clean up legacy plastic pollution.

“The way societies produce, use and dispose of plastic is polluting our ecosystems, creating risks for human health and destabilizing our climate,” said Inger Andersen, United Nations Environment Program executive director, in a news conference on Tuesday held to release one of the two new reports, “Turning off the Tap: How the world can end plastic pollution and create a circular economy.”

And, she said, “we know that people in the poorest nations and communities are those that suffer the most.”

The UNEP’s recommendations for achieving an 80 percent reduction globally in plastic pollution by 2040 included:

Promoting more options for re-using plastic, including refillable bottles, bulk dispensers, deposit-return schemes and packaging take-back programs.

Financially incentivize and stabilize commercial markets to promote more recycling of plastic now, while also removing fossil fuels subsidies and enforcing new design guidelines to make plastic more easily recyclable.

Replace certain types of plastic packaging with other materials, including paper.

“We’re talking about a systemic change, a systems change,” said Sheila Aggarwal-Khan, director of the Industry and Economy Division at UNEP. “That means that you cannot solve just one part of the problem. You cannot simply say, ‘Well, let’s just recycle our way out of the plastic pollution crisis.’ Or you cannot simply say, ‘Let’s just simply do away with single-use plastics.’”

Economic costs of plastic pollution “are running in the hundreds of billions of dollars annually,” Andersen said at the briefing from UNEP headquarters in Nairobi. Plastic waste, she added, is “destroying infrastructure, impacting energy production and tourism revenue, clogging our drains and flooding our cities and potentially impacting human health through exposure to hazardous chemicals.”

The starting point for change, she added, “is to eliminate unnecessary and problematic plastics,” and then to “systemically” change how plastics are made, used and recycled.

UN Officials: Solutions are Within Reach

As the U.N. delegates pack their bags for Paris, countries, industries and environmental groups have already been staking out their positions. The Biden administration’s opening position, dubbed “low ambition” by its critics, calls for individual national action plans as opposed to strong global mandates and does not seek enforceable cuts in plastics manufacturing, even though reducing plastic production was a key recommendation of the landmark 2021 National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine report on the devastating impacts of plastic pollution.

Instead, the U.S. proposal touts the benefits of plastics and calls for improved management of plastic waste such as re-use, recycling and redesigning plastics.

The European Union and a “high ambition” coalition of countries led by Norway and Rwanda are seeking global targets to reduce the production of plastics and phasing out risky chemical additives, such as endocrine disruptors like phthalates, which are used to make plastics pliable and are a threat to human health. They are seeking to end all plastic pollution by 2040.

In its Turning off the Tap report, the U.N. advocated for a circular plastics economy.

“Circularity” has become something of a buzzword touted by industry, governments and some environmental groups, but with no widely accepted definition, to suggest products are repeatedly made from waste without tapping new natural resources. The U.N. report described circularity as a “zero-pollution plastics economy” that “eliminates unnecessary production and consumption, avoids negative impacts on ecosystems and human health, keeps products and materials in the economy and safely collects and disposes of waste that cannot be economically processed.”

UNEP noted that the world produces 430 million metric tons of plastics each year, of which over two-thirds are short-lived products that soon become waste, and a growing amount, or 139 million metric tons in 2021, after a single use. Plastic production is set to triple by 2060 under a “business-as-usual” scenario.

Solutions are within reach, but they will require nations to agree to work together to “transform the plastics economy,” according to the report. Even with such transformation, “a significant volume of plastics cannot be made circular in the next 10 to 20 years and will require disposal solutions to prevent pollution.”

But tackling the problem could save trillions of dollars in costs from the damage plastics cause to health, climate and marine ecosystems, the report found, while creating a net increase of 700,000 jobs by 2040, mostly in low-income countries.

Chemicals in Plastics Threaten Health, Environment

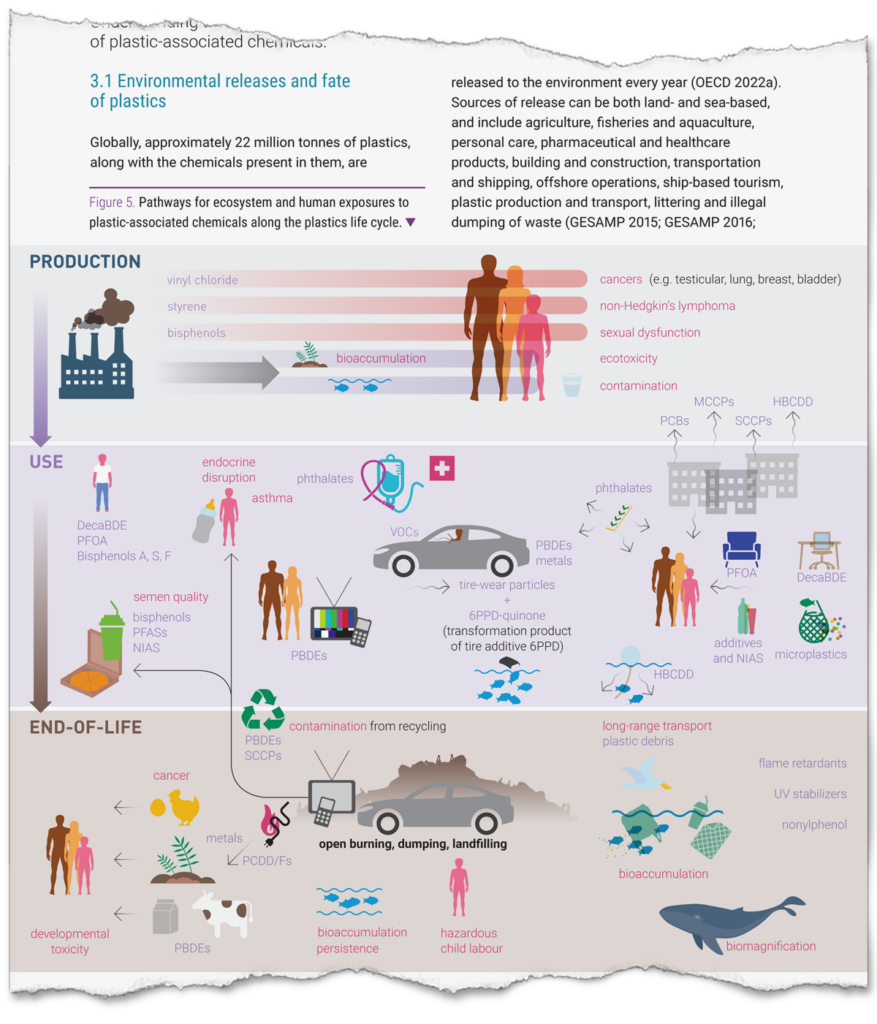

In a report dated May 3, “Chemicals in Plastics,” UNEP focused on the more than 13,000 chemicals associated with plastic products and manufacturing, noting that only about half of them have been screened for properties that would make them hazardous to people or the environment. At least 3,200 of the 7,000 screened chemicals have been identified as potentially of concern, according to the report.

Those chemicals include some that persist for extended lengths of time and accumulate in the environment, where they can wreak havoc on wildlife or people. They include polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs), polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), and some, like per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), which have been dubbed “forever chemicals.”

Many are used, emitted and released throughout the plastic lifecycle, from the extraction of oil and gas and the production of polymers and chemicals to the manufacturing, use and end-of-life management of plastics, according to the U.N. report.

This graphic shows the pathways for human and ecosystem exposure to chemicals that are in plastics. It’s from “Chemicals in Plastics,” a May 2023 report by the United Nations Environment Program. Credit: UNEP and Secretariat of the Basel, Rotterdam and Stockholm Conventions.

“These chemicals have been found to be associated with a wide range of acute, chronic, or multi-generational toxic effects, including specific target organ toxicity, various types of cancer, genetic mutations, reproductive toxicity, developmental toxicity, endocrine disruption and ecotoxicity,” the report concluded.

The varied chemical nature of plastic also makes it harder to recycle; less than 10 percent is now recycled worldwide.

Among that report’s recommendations were to “reduce plastic production and consumption, starting with non-essential plastics,” and “design and manufacture plastics that are free of chemicals of concern.”

UN Officials See Need to Boost Recycling, But Problems Persist

The American Chemistry Council, a leading lobbying group for plastics manufacturers, declined to comment on the U.N. reports.

But the chemical and plastics industries have, through marketing, advertising and lobbying campaigns, promoted the concept of advanced or chemical recycling and what they call “a more circular economy,” that reduces the need to tap virgin fossil fuels to make its products.

The U.N. report released Tuesday puts an emphasis on mechanical recycling, where waste plastics are typically collected, sorted, chopped, heated and molded into new plastic products. That’s even though mechanical recycling carries certain environmental risks, including, according to new research, the production of microplastics.

Inside Climate News on Tuesday reported on new research in the United Kingdom published in the Journal of Hazardous Material Advances. It found that all the chopping, shredding and washing of plastic at a recycling facility turned as much as six to 13 percent of the incoming waste into microplastics—tiny, toxic particles that are an emerging and ubiquitous environmental health concern for the planet and people.

“Mechanical recycling is probably the best that we have,” said Steven Stone, deputy director of the Industry and Economy Division for UNEP. “Even if it’s not perfect, we can certainly improve the technology on mechanical recycling. And importantly, by improving the design of plastic products and improving what goes into the products in the first place, that can also help increase the efficiency of mechanical recycling.”

He said that standards for both the design of plastics and the operations of recycling facilities will be needed.

In the press conference, U.N. officials also described chemical recycling, a type of “advanced” recycling, as not really ready for prime time, and a less desirable option than mechanical recycling.

In January, U.S. government researchers found two prominent “advanced” technologies—pyrolysis and gasification—should not even be considered technologies that are “closed-loop,” another term for the circular economy. Pyrolysis and gasification require large amounts of energy and emit significant pollutants and greenhouse gases to turn discarded plastics into oil or fuel, or other chemical feedstocks, synthetic gases and a carbon char waste product.

“There is a huge carbon footprint on chemical recycling,” Andersen said, adding that “a good number of the chemical recycling (operations) today actually don’t recycle.” Instead, she said, companies are turning waste plastic into “very dirty fuels that can be burned off. And that is obviously not the way we want to go with climate change.”

She also said “there is a justice dimension” with chemical recycling; the plants tend to be located near the poorest people “and those who have the least voice in society.”

Keep Environmental Journalism AliveICN provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going.Donate Now