- Marine scientists from the University of California, Santa Barbara, share their list of the top 10 ocean news stories from 2022.

- Hopeful developments this past year include the launch of negotiations on the world’s first legally binding international treaty to curb plastic pollution, a multilateral agreement to ban harmful fisheries subsidies and a massive expansion of global shark protections.

- At the same time, the climate crises in the ocean continued to worsen, with a number of record-breaking marine heat waves and an accelerated thinning of ice sheets that could severely exacerbate sea level rise, underscoring the need for urgent ocean-climate actions.

- This post is a commentary. The views expressed are those of the authors, not necessarily Mongabay.

1. Negotiations for historic global plastics treaty break ground

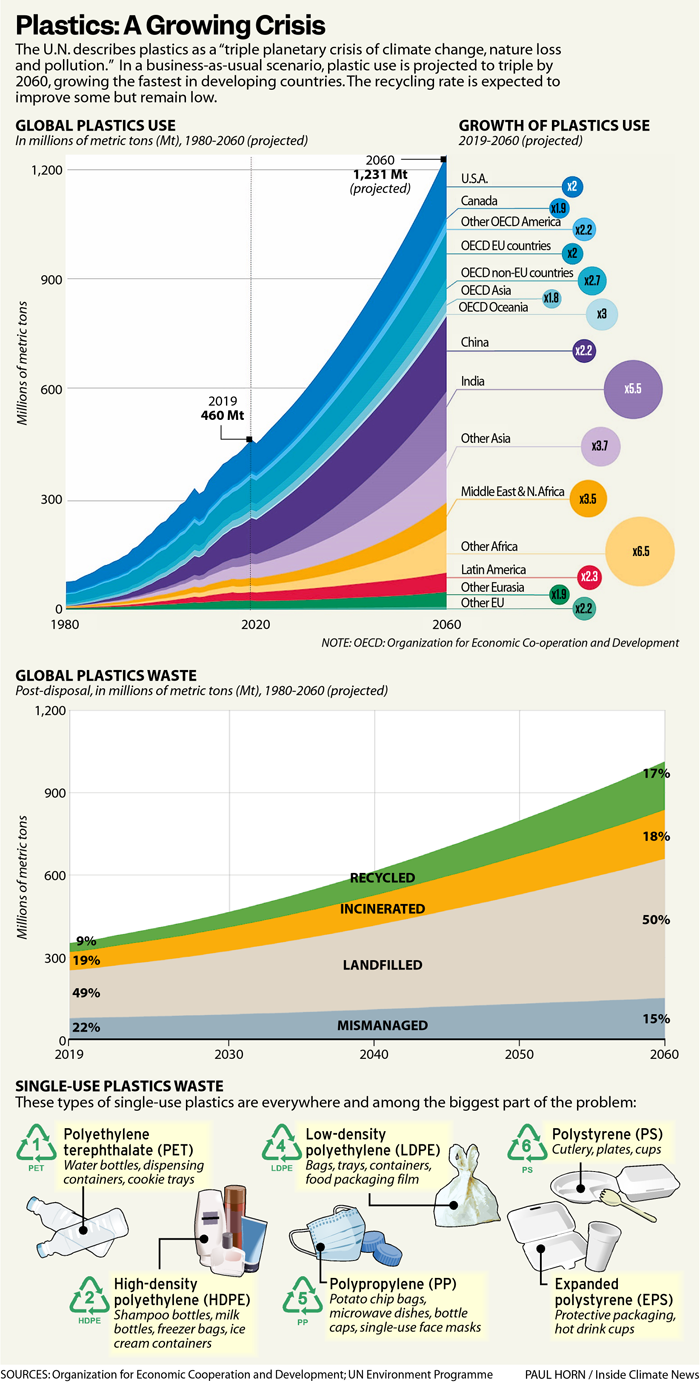

Global leaders cheered to the strike of a recycled-plastic gavel in March, signifying a landmark decision by the United Nations Environment Assembly to create the first-ever legally binding international treaty to curb plastic pollution. With 8.3 billion metric tons of plastic having been produced to date, the decision marks a historic moment in addressing one of our blue planet’s greatest crises.

Negotiations for the global plastics treaty began in November in Uruguay, where representatives from more than 150 countries came together to start discussing details and goals. This International Negotiating Committee (INC) aims to finalize a formal treaty in a series of upcoming meetings by the end of 2024.

Without major efforts to reduce plastic pollution, projections show that 12 billion metric tons of plastic waste could end up in the natural environment or landfills by 2050. Plastic accounts for 85% of marine debris already, and the volume of plastic in the ocean may triple by 2040. Some groups are working to curb this pollution by capturing plastic waste in river mouths before it enters the sea. The Clean Currents Coalition, a global cleanup network facilitated by our team at the Benioff Ocean Science Laboratory at the University of California Santa Barbara, has collected nearly 1,000 metric tons of plastic from rivers in eight countries. However, it’s going to take more than a few trash wheels to solve the problem.

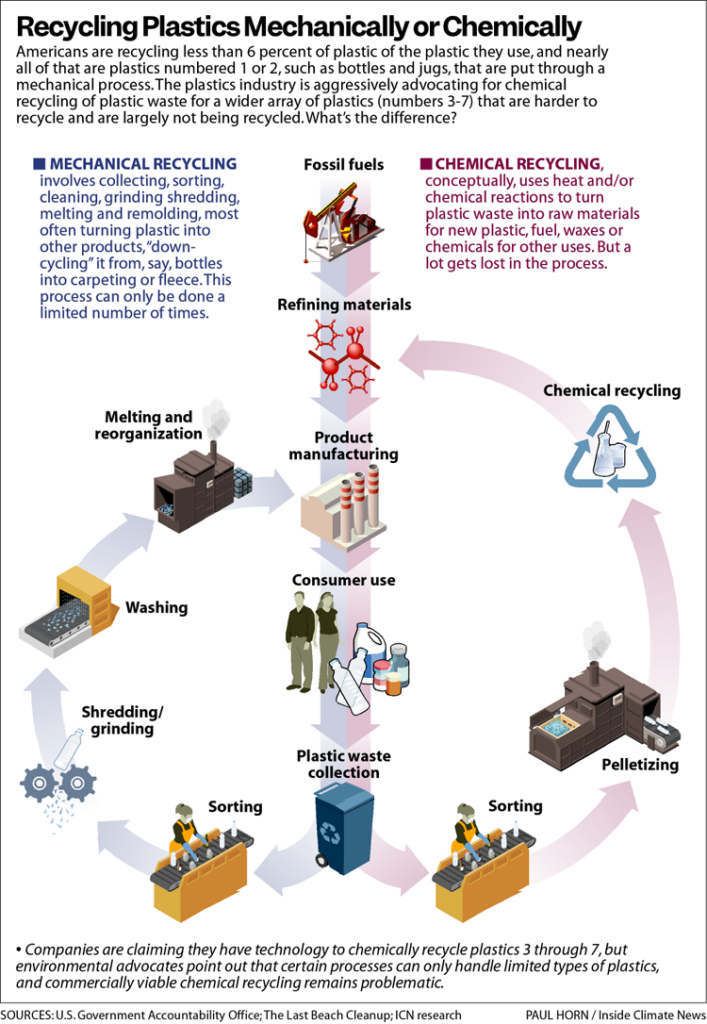

Recycling is also not the entire answer, at least as currently implemented. Of all the plastic ever produced, only 9% has been recycled. Ultimately, it seems we need to reduce our global dependence on this substance, and a legally binding international agreement that operates across the entire supply chain is an essential first step.

2. Sea level rise

One of the primary drivers of sea level rise is the thawing of global ice. A study published in November provided some bleak news from Greenland’s largest ice sheet, suggesting that it is thawing at an accelerated rate and will add six times more water to the ocean than scientists previously thought. The calculations show that by the end of this century, it will add 0.5 inches to the global ocean level, an amount equal to Greenland’s overall contribution to sea level rise over the past 50 years.

Scientists are closely monitoring the Thwaites Glacier in Antarctica, also known as the “Doomsday” glacier, as a new study shows it is capable of shrinking faster than it has in recent years. The glacier is the size of Florida and accounts for about 5% of Antarctica’s contribution to changes in global sea level; if it were to collapse into the ocean, it could cause a rapid rise in sea levels. Focusing on just the United States, NASA released a study in October showing the average level of sea rise for the majority of coastlines in the contiguous United States could reach 30 centimeters (12 inches) by 2050.

The analysis draws on almost three decades of satellite data, and the results could help coastal communities prepare adaptation plans for the coming years, which may bring an increase in flooding. The estimated waterline increase will vary regionally: 25-36 cm (10-14 in) for the East Coast, 36-46 cm (14-18 in) for the Gulf Coast and 10-20 cm (4-8 in) for the West Coast. Experts cite climate change as a leading cause of the sea level rise, along with natural factors, such as El Niño and La Niña events and the moon’s orbit.

3. A major milestone in shark and ray protection

In November, governments from around the world came together at the 19th Conference of the Parties (CoP19) to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) in a massive showing of leadership to increase the protection of nearly 100 species of sharks & rays. CoP19 parties voted to list 54 species of requiem sharks, six species of hammerhead sharks and 37 species of guitarfish under CITES Appendix II.

The designation limits international trade and grants greater protection to these species, many of which are threatened with extinction by the unsustainable global trade in their fins and meat. This is a huge win for shark conservation as it brings 90% of the internationally traded shark species under CITES protection. Previously only 20% had been protected. International trade of these species will only be permitted if they are not endangered as a result, and will require an export permit to ensure that legal and sustainable trade is taking place.

The proposals were championed by Panama, the host country, and co-sponsored by more than 40 other CITES-party governments. It is one of 46 proposals that was adopted by the delegation at the conference and reaffirms international commitments to protect both terrestrial and marine species that are impacted by the global wildlife trade. In addition to the nearly 100 species of sharks and rays, the parties voted to increase the protection of 150 tree species, 160 amphibian species, 50 turtle and tortoise species and several species of songbirds.

4. Momentum builds for a global moratorium on seabed mining

2022 marked a dramatic change in what previously appeared to be an almost inevitable march toward the start of the controversial emerging industry of deep-sea mining. Marine policy experts deemed that the “two-year rule” triggered by Nauru in 2021 had unclear legal footing and implementation, undercutting efforts to see seabed mining start as soon as July 2023 under whatever regulations are in place at the time.

Scientists this year also came together to highlight substantial scientific gaps in our understanding of the environmental impacts of seabed mining. Countries, businesses and scientists also united in strengthening a call for a global moratorium, or pause, on seabed mining. In a major shifting of political winds at the June-July UN Ocean Conference in Lisbon, Pacific states, including Palau, Fiji, Samoa and the Federated States of Micronesia, led an alliance calling for a moratorium. France later became the first nation to call for a complete ban on the activity. Twelve nations have now taken formal positions against deep-sea mining in international waters this year.

Amid this growing opposition, the International Seabed Authority approved its first mining trials since the 1970s. These commenced in September in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone, an area beyond national jurisdictions in the Pacific Ocean that contains rare-earth elements and metals. In November, a new report suggested that seabed minerals may not be necessary at all and that their demand could instead be met by recycling and existing terrestrial reserves.

5. Asia-Pacific ocean leadership

The Asia-Pacific region is home to the most biologically diverse and productive marine ecosystems. The countries in this region are also characterized by having a larger population and stronger economic growth than any other region. And yet many global conversations calling for increased ambition in ocean leadership have historically lacked Asia-Pacific representation. 2022 suggested a turning of that tide. The G20, hosted this year in Indonesia, included an entire summit, the O20, devoted to ocean health issues. There appears to be nascent interest in carrying this leadership tradition forward at the next G20 summit, to be hosted in September by India. Similarly, Japan will host the G7 summit in Hiroshima next May and has engaged in discussions to elevate the UN’s Sustainable Development Goal 14, which deals with the ocean, as a major topic.

With the rising threat of climate change, countries in the Asia-Pacific region have turned their attention this year to blue carbon. China, which lost more than half of its mangrove swamps between 1950 and 2001, is making some initial progress in protecting its marine ecosystem by creating an international mangrove center, national standards for coral reef restoration and its first comprehensive methodology for blue carbon accounting. At COP27, the UN climate conference that took place in November in Sharm El Sheikh, Egypt, the establishment of the International Blue Carbon Institute was announced. The institute will serve as a knowledge hub to develop and scale blue carbon projects. It will be housed in Singapore to focus on supporting Southeast Asia and the Pacific Islands.

Indonesia has taken action to slow the loss of its mangroves, the world’s largest collection, through multiple initiatives such as launching the Mangrove Alliance for Climate. This slow but steady emerging leadership in oceans by countries in the Asia-Pacific region is a promising sign.

6. Outer space ocean

Oceans may not be as exclusive to Earth as we previously thought. A new study reveals that 4.5 billion years ago Mars had enough water to be covered in an ocean as deep as 300 meters (nearly 1,000 feet). The Mars that we know in the present day is a reddish color and averages temperatures of negative 62 degrees Celsius (negative 80 degrees Fahrenheit), making it unable to support water in any form other than ice. During the first 100 million years of Mars’ evolution, ice-filled asteroids that carried organic molecules crashed on the planet, allowing for conditions supportive of life to emerge long before they did on Earth.

Because Mars does not have plate tectonics, the surface preserves a historical record of the planet’s history; researchers were able to gain insight into the red planet’s wetter past, as well as into the formation of the solar system, from a meteorite found on Earth that was part of Mars’ original crust billions of years ago.

7. Ocean giants

This year brought both ups and downs for the world’s largest charismatic marine megafauna: whales. Scientists are looking into what is causing a 40% decline in birth rates of the Pacific gray whale (Eschrichtius robustus) population that travels along the U.S. West Coast on its migration from Baja, Mexico, back to the Arctic. This past year’s decline brings the birth rate to the lowest level since 1994. The scarcity of food sources in their Arctic feeding grounds due to climate change is one main factor scientists say they believe is contributing to the decline.

Another study showed that blue, fin and humpback whales feed at 50-250 meters (164-820 feet) below the surface, which coincides with the ocean’s highest concentrations of microplastics. The authors estimated that blues ingest 10 million pieces per day. Some progress was made on mitigating one of the largest threats to large whales: ship strikes.

The waters off the southern coast of Sri Lanka are important blue whale habitat for feeding and nursing, but also a busy shipping lane that creates a high risk for fatal collisions. The largest container line in the world has started ordering its ships to slow down in this region and travel outside the known whale habitat, helping to reduce the risk of collisions by 95%. The tech-driven platform Whale Safe (one of our projects at the Benioff Ocean Science Laboratory), designed to prevent whale-ship collisions and piloted in southern California, was replicated and deployed in the San Francisco region, helping to create a safer environment for whales off the U.S. West Coast.

8. Explosive interest in blue carbon

Climate change continues to be the biggest threat facing our ocean and planet. 2022 brought a happy but belated influx of investment and attention to blue carbon, a term that refers to using mangroves, tidal marshes, seagrass beds, and other marine ecosystems to sequester carbon dioxide in the fight against climate change.

Mangroves have the potential to store up to 10 times as much carbon as tropical rainforests. In addition to the pivotal role they might have in preventing climate change, blue carbon ecosystems also protect coastal communities from flooding and storms and provide habitat for marine life. As a result, protecting these marine ecosystems was a key topic at COP27, a focus of research by academic institutes and an area of investment by companies such as Google and Salesforce (whose co-founder, Marc Benioff, also funds the Benioff Ocean Science Laboratory, where we work).

Australia’s national science agency, CSIRO, and Google announced a $2.7 million blue carbon AI research project that will help researchers understand blue carbon ecosystems in the Indo-Pacific and Australia. At COP27, Salesforce, the World Economic Forum’s Friends of Ocean Action and a global coalition of ocean leaders announced the High-Quality Blue Carbon Principles and Guidance, a blue carbon framework to guide the development and purchasing of high-quality blue carbon projects and credits. In the last decade alone, the oceans have absorbed about 23% of carbon dioxide emitted by human activities and investment in their protection and recovery will be vital to the overall fight against climate change.

9. Marine heat waves and coral reefs

Record-breaking heat events took place across the globe this year, and not just on land. Rising ocean temperatures are a cause for concern because they increase stress on already vulnerable ecosystems like coral reefs. The sea surface temperatures over the northern part of the Great Barrier Reef were the warmest November temperatures on record, raising fears this may be the second summer in a row of a massive coral bleaching event that affected 91% of surveyed reefs last year.

The news isn’t all bad, though. Innovative finance mechanisms are being leveraged to protect coral reefs from these threats. In Hawai’i, The Nature Conservancy purchased an insurance policy to protect the state’s reefs from hurricanes and tropical storms. If wind speeds reach 50 knots (57.5 mph) or more, the policy will pay out, allowing for rapid reef repair. This is the first policy of its kind in the U.S., although similar approaches have been used in Mexico, Belize, Guatemala and Honduras. Creative finance solutions like this will continue to be a key component of protecting these vital ecosystems.

10. A decisive year for the ocean

2022 was a big year for ocean policies, marked by a number of breakthroughs by the international community, some of which had been long-awaited after pandemic-induced delays. Major themes addressed reducing plastic pollution, protecting marine biodiversity, supporting the blue economy, decarbonizing shipping and more. Key policy moments included a landmark deal to ban harmful fishing subsidies that was reached after 20 years of negotiations at the World Trade Organization. The historic agreement specifically prohibits subsidies to illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing and to fisheries targeting overexploited fish stocks. At the UN Ocean Conference, member states made more than 700 conservation commitments pledging to expand marine protected areas, end destructive fishing practices, increase investments and expand blue economies.

More than 100 nations have affirmed voluntary commitments to protect 30% of their oceans by 2030. At the conference, the Protecting Our Planet Challenge announced it will invest at least $1 billion to support this goal. Several countries also announced plans to create and expand marine protected areas, including Colombia, which, if it fully implements its plan, would become the first country to achieve the 30% goal ahead of the 2030 target.

In November, the Green Shipping Challenge launched at COP27, with more than 40 announcements by countries, ports, and companies detailing measures to decarbonize shipping, an industry that currently emits close to 3% of global greenhouse gas emissions. Many of the announcements were related to green shipping corridors and technological developments for climate-neutral ships, such as innovative propulsion systems, sailing cargo ships and the production of low- and zero-emission fuels.

Finally, to cap off 2022, after two years of delay from the pandemic, the UN conference on the Convention on Biological Diversity (COP15) took place in Montreal. Early on the morning of Dec. 19, delegates reached a historic new global biodiversity agreement that outlines 23 conservation targets to prevent biodiversity loss over the next decade, including protecting 30% of land, fresh water and the ocean by 2030. During negotiations, there were strong disagreements among delegates about how much funding was needed to reach these goals and who should pay for it. In the final agreement, nations collectively committed to spending $200 billion per year on biodiversity conservation.

Callie Leiphardt is a project scientist at the Benioff Ocean Initiative, where she works on projects to develop science- and technology-based solutions to ocean problems, such as the Whale Safe project to reduce fatal whale-ship collisions along the California coast. Her background is in conservation planning, particularly with marine mammals. Douglas McCauley is an associate professor at the University of California, Santa Barbara, and director of the Benioff Ocean Science Laboratory. Neil Nathan is a project scientist at Benioff Ocean Science Laboratory, where he works on issues such as deep-sea mining, marine protected areas in the high seas and shark monitoring using drones and artificial intelligence. Nathan has a background in natural capital approaches, which aim to incorporate the value of ecosystem services into decision-making and planning. Rachel Rhodes is a project scientist at the Benioff Ocean Science Laboratory, where she works on Whale Safe. Her background is in marine geospatial data and strategic environmental communications. Aaron Roan leads technology and engineering initiatives across projects at the Benioff Ocean Science Laboratory. He comes from Google and Slack and has spent more than a decade using technology, machine learning and data to help with ocean science and conservation.

Banner image: A whale shark swimming with remoras in Ras Mohammed National Park, Egypt. Image by Cinzia Osele Bismarck / Ocean Image Bank.

Citations:

Geyer, Roland, Jenna R. Jambeck, and Kara Lavender Law. “Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made.” Science Advances 3.7 (2017). doi:10.1126/sciadv.1700782.

Khan, S. A., Choi, Y., Morlighem, M., Rignot, E., Helm, V., Humbert, A., … Bjørk, A. A. (2022). Extensive inland thinning and speed-up of Northeast Greenland ice stream. Nature, 611(7937), 727-732. doi:10.1038/s41586-022-05301-z

Graham, A. G., Wåhlin, A., Hogan, K. A., Nitsche, F. O., Heywood, K. J., Totten, R. L., … Larter, R. D. (2022). Rapid retreat of thwaites glacier in the pre-satellite era. Nature Geoscience, 15(9), 706-713. doi:10.1038/s41561-022-01019-9.

Hamlington, Benjamin D., et al. “Observation-based trajectory of future sea level for the coastal United States tracks near high-end model projections.” Communications Earth & Environment 3.1 (2022). doi:s43247-022-00537-z.

Amon, Diva J., et al. “Assessment of scientific gaps related to the effective environmental management of deep-seabed mining.” Marine Policy 138 (2022). doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2022.105006.

Zhu, Ke, et al. “Late delivery of exotic chromium to the crust of Mars by water-rich carbonaceous asteroids.” Science Advances 8.46 (2022). doi:eabp8415.

Kahane-Rapport, S. R., Czapanskiy, M. F., Fahlbusch, J. A., Friedlaender, A. S., Calambokidis, J., Hazen, E. L., … Savoca, M. S. (2022). Field measurements reveal exposure risk to microplastic ingestion by filter-feeding megafauna. Nature Communications, 13(1). doi:10.1038/s41467-022-33334-5

Wylie, Lindsay, Ariana E. Sutton-Grier, and Amber Moore. “Keys to successful blue carbon projects: lessons learned from global case studies.” Marine Policy 65 (2016). doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2015.12.020

FEEDBACK: Use this form to send a message to the editor of this post. If you want to post a public comment, you can do that at the bottom of the page.