Cities are turning to “trash skimmers” to rid their waterways of plastic waste. But environmentalists say the boats are more of a Band-Aid than a solution.via City of TampaAs plastics accumulate in rivers and bays, localities across the country are seeking creative, affordable solutions to keep their waterways clean. Many have turned to “trash skimmers,” boats that are designed to remove litter.Tampa, Fla., is one of the latest cities to invest in such a vessel, a $565,000 boat that it has named the “Litter Skimmer.” It skims single-use plastics and other trash — as well as organic materials such as branches and leaves — from the water and onto a conveyor belt that pulls it into a storage area, a city spokesman said.The boat debuted about a year ago and has since gathered about 13 tons of debris, said Alexis Black, an environmental specialist with Tampa’s Department of Solid Waste and Environmental Program Management.As far back as the 1950s, scientists have been warning that marine life was getting stuck in discarded fishing gear and other types of plastic waste. Since then, consumption of single-use plastics has risen to the point where tens of millions of tons of plastic enter Earth’s oceans each year. Over the years, plastics have harmed local ecosystems and disrupted storm water management, leading to flooding.The skimmer is only one method that Tampa is using to remove waste from its local waters. The city also organizes community cleanup events along its waterways and in its parks, and uses tools like baffle boxes and netting to keep debris from leaving storm drains and going into the river.“The introduction of Litter Skimmer was just to add an extra layer of the strategy to combat the litter that makes it into the water bodies,” Ms. Black said. “It’s a great step to capture a lot of the waste that in the past was just left to float down the river in the bay and beyond.”Trash skimmers have long been part of municipal efforts to clean up waterways. Washington, D.C., began using skimmer boats in 1992 and added two more to its fleet in 2017, for $484,000 each. The Passaic Valley Sewerage Commission in New Jersey unveiled its first trash-collecting vessel in 1998 and purchased a second in 2018 for about $653,000.D.C. Water, Washington’s water utility, said that its boats collect 300 to 500 tons of waste each year. The Passaic Valley Sewerage Commission said its boats gather 160 tons of waste annually.Carroll Muffett, president of the Center for International Environment Law, a nonprofit that focuses on environmental issues, said the skimmer boat programs are well-intentioned, but such efforts do little to address the overall problem of plastic pollution.While skimmers are designed to collect larger pieces of floating trash, many plastics are too small for the vessels to capture, Mr. Muffett said. A 2019 study from the University of South Florida St. Petersburg and Eckerd College estimated that four billion particles of microplastics — which are less than one-eighth of an inch long — are in the Tampa Bay.Most municipal skimmers also have limited hours of operation, Mr. Muffett said. The skimmer in Tampa, for instance, runs 10 hours a day, four days a week, typically operated by two people.“You begin to understand that this is only a tiny Band-Aid on what is a massive problem,” he said. “What it also represents is the massive investment that cities, counties and states are making in cleaning up this problem.”There isn’t just a policy responsibility; it’s a personal one as well, said John Atkinson, an associate professor of civil, structural and environmental engineering at the University at Buffalo.“We’re a culture that is reliant on plastic,” Professor Atkinson said, adding that “choosing to use a reusable water bottle, while small, can be substantial if everybody chooses it.”Policies that reduce the overall use of plastic, such as bans on single-use disposable plastics, would be more effective, he said.“We cannot scoop, we cannot shovel, we cannot net, we cannot recycle our way out of the plastics crisis,” Mr. Muffett said. “The only way we address the plastics crisis is by producing — and using and losing — fewer plastics.”

Category Archives: Land

Geoffrey Lean: Whisper it, but the boom in plastic production could be about to come to a juddering halt

Plastic production has soared some 30-fold since it came into widespread use in the 1960s. We now churn out about 430m tonnes a year, easily outweighing the combined mass of all 8 billion people alive. Left unabated, it continues to accelerate: plastic consumption is due to nearly double by 2050.Now there is a chance that this huge growth will stop, even go into reverse. This month in Paris, the world’s governments agreed to draft a new treaty to control plastics. The UN says it could cut production by a massive 80% by 2040.Such a treaty – scheduled for agreement next year – cannot come soon enough.The amount of plastic dumped in the oceans is due to more than double by 2040. Producing single-use plastic alone emits more greenhouse gases than the whole UK. And microplastics have been found in human blood, lungs, livers, kidneys and spleens – and have crossed the placenta. No one knows the full effects on the planet – or the impact of the 3,200 potentially harmful chemicals in plastics on our health.Governments finally began to call a halt in March last year, resolving to “end plastic pollution” at a meeting of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and calling for a series of negotiating meetings on a possible treaty. The recent meeting in Paris was the second such “plastic summit”. Three more are scheduled before the end of next year.Whisper it, but – with hard work, determination and a lot of good luck – the plastics treaty might join the Montreal protocol on substances that deplete the ozone layer as a landmark success in environmental diplomacy.It has several important advantages. It is backed by immense public concern – uniting a whole range of issues from litter to the oceans, human health to climate breakdown – which can be translated into political pressure. And no new technology is needed: UNEP says the 80% reduction can be achieved using proven practices.These include simply eliminating much unnecessary single-use plastic packaging, ensuring reuse, and replacing many instances of plastic use with more sustainable biodegradable materials. Governments could also discourage the production of new plastics by taxing it and removing industry subsidies.Crucially, like the negotiations over ozone, it has some strong business support. A 100-strong Business Coalition for a Global Plastics Treaty – which includes giant users of plastics such as Unilever and Coca-Cola – is pressing for tough regulatory measures.And, as in recent successful UN agreements, an alliance of governments committed to change is leading the charge. This High Ambition Coalition includes all G7 countries except Italy and the US. Importantly, Japan – which had opposed a strong treaty – recently switched sides to join it.UNEP also has a good record of cementing treaties. It has brokered a host of pacts, covering issues from wildlife to toxic wastes, and the historic Montreal protocol.That protocol – the first treaty to be ratified by every country on Earth – has phased out the use of nearly 100 substances that attack the planet’s protective ozone. As a byproduct, it has done more to slow climate breakdown than any other international agreement, since many of those substances also heat the atmosphere.None of this means it will be easy. When I was reporting the story, I was told that agreeing the Montreal protocol was so dicey that the text could not immediately be translated from English into the other five official UN languages for fear of upsetting its delicate verbal compromises.Weighty, determined opposition to radical measures comes from a powerful minority of plastic-producing countries including China, India and the US. And companies that have obstructed action on global heating are mobilising. Ninety-nine per cent of plastics are made with fossil fuels and the industry is determined to expand their production to offset what it is losing to clean sources of energy.There are three main sources of contention. The majority of countries want binding global rules, while their opponents insist on voluntary ones. Most countries want to limit plastics production and ban dangerous substances, while the manufacturers focus on recycling what is produced.And the majority want decisions to be made by vote, while many of those opposed want to keep a veto by demanding consensus. This issue held up substantive talks in Paris for two days, and is still unresolved. And beyond all this lies the ever-thorny question of who will pay for the change.All in all, some kind of treaty is likely to emerge. How strong and effective it is will depend on how these issues are settled.

Geoffrey Lean is a specialist environment correspondent and author

Satellites, drones join fight against air pollution in Pennsylvania

A cluster of colors indicates methane gas released from a coal mine vent in Pennsylvania. (Carbon Mapper)

In the summer of 2021, a twin-engine special research aircraft took off from State College, PA. Over three weeks, the plane flew 10,000–28,000 feet over oil and gas wells, landfills and coal mines in four regions of the state. The mission was to pinpoint sources of high levels of methane gas, or “super emitters,” for the nonprofit group Carbon Mapper and its funding partner, U.S. Climate Alliance.From a hole cut in the belly of the plane, they trained a camera-like device developed by NASA — an imaging spectrometer — that uses light wavelengths to pick up escaping plumes of methane. Methane emissions are the second-largest cause of global warming after carbon dioxide, and controlling them is increasingly considered a key to arresting climate change.

Methane is invisible to the naked eye. But spectrometers, and devices like them, detect and measure the infrared energy of objects. The cameras then convert that data into a three-dimensional electronic image.For the 2021 aerial probe, Carbon Mapper targeted areas of generally high methane levels that the organization had previously located using readings from space satellites operated by the European Space Agency.During the flights, the researchers found 63 super emitters. Most, they concluded, were the results of leaks and malfunctioning equipment.The Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection, which collaborated in the project, was thrilled by the reactions they received when they took the results to the sources of the highest emissions. The operators of six landfills and six oil and gas wells responded by voluntarily fixing equipment or taking other steps to reduce emissions.“That’s a really positive thing. This is existential proof that making methane visible can lead to voluntary action,” said Riley Duren, Carbon Mapper CEO and founder.In Pennsylvania, the use of this and other technology has energized a new breed of environmental activism aimed at detecting air pollution from the sky and from the ground. Their tools include satellites, airplanes with specially equipped air monitors and ground-based remote-sensing cameras like those used by government regulators and gas operators to find leaks.Sometimes, communities and groups use these devices to document problems. They also use them to document air quality before gas wells or petrochemical plants are built.“It’s not our parents’ or grandparents’ environmentalism. It’s definitely not just sitting in trees. It’s a different type of environmentalism and it’s much more sophisticated,” said Justin Wasser of Earthworks, a national environmental group that helps communities fight oil, gas and mining pollution.High tech eyesLater this year and in early 2024, Carbon Mapper and its partners, which include NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and Planet Labs, plan to launch two satellites to monitor methane emissions around the world. The first phase of the monitoring program has a $100 million budget, all funded by philanthropy.Also early next year, a satellite dubbed MethaneSAT, funded by such high-profile financial backers as Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos, is scheduled to begin orbiting the Earth to monitor methane emissions.“Methane satellites are going to dramatically change this work. This time next year, you and I are going to be talking about how astronomically large this problem is and why we haven’t been working on this for years,” Earthwork’s Wasser said.Since 2020, the Pennsylvania-based group, FracTracker Alliance, has used ground monitors in southwestern Pennsylvania to document the cumulative effect of air pollution from fracking wells and petrochemical plants.

Colored blobs from an imaging spectrometer operated from an airplane indicate methane gas releases from a natural gas well pad (top) and from vents in a coal mine (bottom) in Pennsylvania. (Courtesy of Carbon Mapper)

Now, armed with a $495,000 federal grant from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, the group has purchased a drone that will carry infrared cameras over wells and gas-related petrochemical plants, looking for methane releases as well as smog-forming chemicals and volatile organic compounds. The grant is part of a new federal initiative to enhance air quality monitoring in communities across the U.S.“This kind of camera never seemed possible before. It seemed like a wish list,” said Ted Auch, FracTracker’s primary drone operator. “We’ll be deploying drones in a lot of hard-to-reach spots like up a hill, in a hollow, around a corner. We can pinpoint smokestacks.”The group hopes that the data it yields will bolster the group’s stance that new gas well permits should be granted only after considering an area’s cumulative air quality, executive director Shannon Smith said.Christina Digiulio, a retired analytical chemist now working for the Pennsylvania chapter of Physicians for Social Responsibility, gets busy when she fields a health complaint from a resident living near a gas well, gas-based petrochemical plant or a landfill that’s accepting fracked-gas waste.A certified thermographer, she lugs a $100,000 gas-imaging forward-looking infrared (FLIR) camera to a gas well pad or the fence line of an industrial plant to look for plumes of methane and volatile organic compounds.“We are using technology now that the industries have kept to themselves. We are an extension of our own regulatory agencies,” she said.

This infrared camera was used to capture images of methane escaping a natural gas well in Lycoming County, PA. (Courtesy of Earthworks)

Getting resultsEnvironmental groups that share findings from their high-tech devices with regulators and gas operators report mixed results.After the 2021 flights departing from State College, Carbon Mapper found that 60% of the methane releases documented were coming from vents in active and old underground coal mines — more than from oil and gas sources combined. Although venting is allowed to prevent the buildup of gases for safety reasons, regulators and researchers alike were surprised at the volume.But the coal industry did not cooperate in measuring emissions from the mines and threatened criminal trespass charges for flying over them, DEP’s Sean Nolan told the agency’s Air Quality Technical Advisory Committee.For the past two years, Melissa Ostroff, a thermographer for Earthworks, has roamed Pennsylvania with a handheld FLIR camera looking for fugitive methane and other invisible pollutants leaking from hundreds of active and abandoned oil and gas well sites as part of the group’s Energy Fields Investigations team.Of 52 instances of methane leaks she has reported to DEP, the agency sent someone to inspect the sites 31 times. Often, she said, equipment malfunctions causing the emissions were fixed.

A camera that sees infrared lightwaves captured this daytime image of methane emissions (the orange “smoke”) from a gas-fired power plant in Pennsylvania. These emissions are not visible to the naked eye. (Physicians for Social Responsibility PA)

In one of her most visible investigations, Ostroff found a gas well leaking methane gas in a popular park in Allegheny County. She reported the pollution to both the gas company and DEP. Within days, the leak was repaired with new equipment installed.Digiulio once detected emissions coming from a compressor station on a liquid natural gas pipeline being built in the eastern part of the state. She notified her state senator, who determined that the company did not have a permit for releases. Work stopped until a permit was obtained.But some environmental groups said that their reports to regulators of unauthorized pollution go unchecked or that operators are allowed to fix problems without being cited for violations.On May 11, the Environmental Integrity Project and Clean Air Council filed a federal lawsuit to halt illegal releases of pollutants from a massive Shell plant using natural gas to produce plastics near Pittsburgh.The groups cite unpermitted releases of pollutants recorded, in part, by high-tech air monitors that Shell agreed to install as part of a previous settlement agreement.Funding boostsThe increased use of citizen science is getting support from the federal government.Under the EPA’s proposed new nationwide rules to regulate methane gas, oil and gas drillers would be required to act on potential leaks at super emitter sites found by third parties, such as environmental nonprofits, universities and others.In a separate initiative, the EPA has announced $53 million in grants in 37 states, including the Chesapeake Bay states of Pennsylvania, Virginia, Maryland, New York and West Virginia, to fund grassroots monitoring efforts in communities. The money will help pay for the purchase and deployment of various devices communities can use to detect air pollution, emissions and possible causes of health problems.

Melissa Ostroff, a licensed thermographer for the environmental group Earthworks, uses an infrared camera to detect methane leaks from a natural gas well in Pennsylvania.(Courtesy of Earthworks)

Pennsylvania will receive 11 grants under the program, with four supporting work by the Environmental Health Project to analyze air quality data as well as helping communities to understand it. A grant to the Maryland Department of the Environment will help reduce air pollution found by sensors in three environmental justice communities, and Virginia will receive two grants to enable the Upper Mattaponi Indian Tribe to set up an air quality program in their community.The aid for monitoring “will finally give communities, some who for years have been overburdened by polluted air and other environmental insults, the data and information needed to better understand their local air quality and have a voice for real change,” said Adam Ortiz, EPA administrator for Mid-Atlantic region.Though thrilled to access equipment that can help amass hard evidence of pollution, some environmental groups are wary that they may have an increased role in protecting public health when it is the responsibility of government agencies to do just that.“The data does not have the weight of EPA’s Clean Air Act’s requirements,” said Nathan Deron, the environmental data scientist for the Environmental Health Project. “At the end of the day, it’s up to DEP and other state regulators to listen to communities and act on the data that is being gathered.”“We have more advanced technology. The gas industry does, too. But that, in itself, is not enough to influence policy if the political will isn’t there,” FracTracker’s Smith added. “We want to influence regulators to put in more protections.”

World Ocean Day: How much plastic is in our oceans?

According to UNESCO, 8-10 million tonnes of plastic are released into the sea every year. On World Ocean Day, Al Jazeera visualises what that looks like.Every year, about 400 million tonnes of plastic products are produced around the world. About half are used to make single-use items such as shopping bags, cups and packaging material.

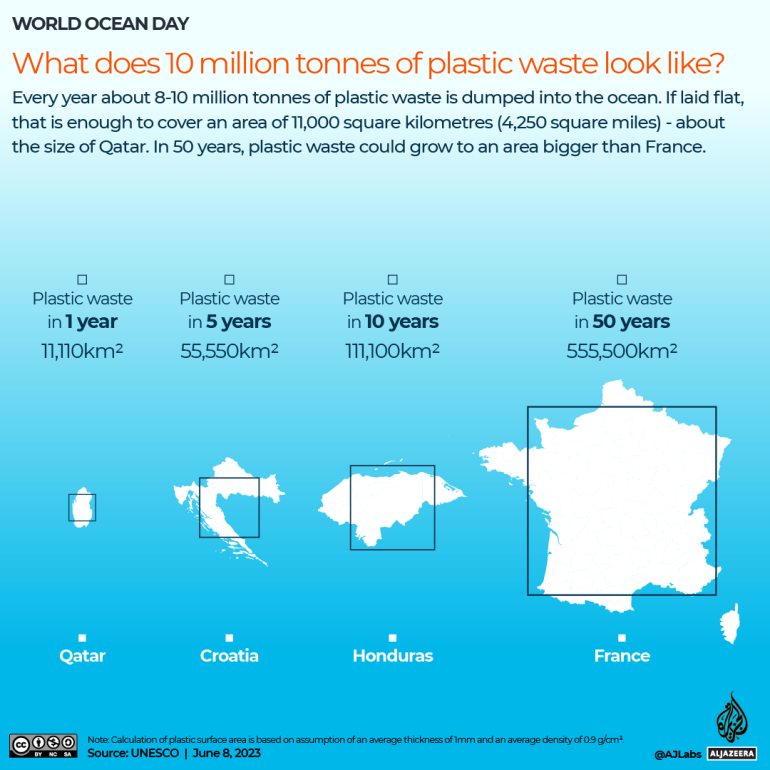

Of these plastics, an estimated 8 million to 10 million tonnes end up in the ocean each year. If flattened to the thickness of a plastic bag, that is enough to cover an area of 11,000sq km (4,250sq miles). That is about the size of small countries like Qatar, Jamaica or the Bahamas.

At this rate, over the course of 50 years, plastic waste could grow to an area bigger than 550,000sq km (212,000sq miles) – about the size of France, Thailand or Ukraine.

To raise awareness about the importance of the ocean and promote its sustainable use and protection, the United Nations designated every June 8 as World Ocean Day.

(Al Jazeera)

How does plastic end up in the ocean?

Plastics are the most common form of ocean litter, comprising 80 percent of all marine pollution. Most plastics that end up in the ocean come from improper waste disposal systems that dump rubbish in rivers and streams.

Plastics in the form of fishing nets and other marine equipment are also dumped into the ocean by ships and fishing boats.

Besides plastic bags and containers, tiny particles known as microplastics also make their way into the ocean. Microplastics, which are less than 5mm (one-fifth of an inch) in length, are a major environmental concern because they can be ingested by marine life and cause harm to both animals and humans.

An estimated 50 trillion to 75 trillion pieces of microplastics are in the ocean today.

(Al Jazeera)

While research on the health effects of human consumption of microplastics is limited, some studies have indicated that microplastics can accumulate in organs such as the liver, kidneys and intestines. There are concerns that microplastic particles could potentially lead to inflammation, oxidative stress and cellular damage.

“These little particles in the ocean were breaking into little pieces and being consumed by the wildlife living there at an almost unimaginable scale. The main problem is that pieces of plastic contain toxic chemicals and these chemicals are already known to interfere with human hormones and animal hormones. They may cause the accumulation of toxins in the body that may lead to ill effects over time,” science writer and author Erica Cirino told Al Jazeera’s The Stream programme.

Which countries are the source of the most plastic in the ocean?

According to a 2021 study published by Science Advances research, 80 percent of all plastics found in the ocean comes from Asia.

The Philippines is believed to be the source of more than a third (36.4 percent) of all plastic waste in the ocean followed by India (12.9 percent), Malaysia (7.5 percent), China (7.2 percent) and Indonesia (5.8 percent).

These amounts do not include waste that is exported overseas that may be at higher risk of entering the ocean.

(Al Jazeera)

What makes plastics so dangerous for the environment?

Plastics are synthetic materials made from polymers, which are long chains of molecules. These polymers are typically derived from petroleum or natural gas.

The main problem with plastics is that they do not easily biodegrade, which means they can persist in the environment for hundreds of years, causing serious pollution problems.

Plastics that find their way into the ocean end up floating on the surface for a long time. Eventually, they sink to the bottom and get buried in the seafloor.

Plastics on the surface of the ocean represent 1 percent of the total plastics in the ocean. The other 99 percent are microplastic fragments far below the surface.

Plastic bottles, wooden planks, rusty barrels and other rubbish clog the Drina river near the eastern Bosnian town of Visegrad on May 25, 2023 [Eldar Emric/AP]

Plastics treaty draft underway, but will the most impacted countries be included?

Negotiators at last week’s global plastics treaty talks in Paris agreed to create an initial treaty draft, but full inclusion of the countries and people most impacted by plastic pollution remains uncertain.

The burdens of plastic pollution land heavily on low- and middle-income countries. High-income countries generated

87% of exported plastic waste between 1998 and 2016. Much of that exported plastic goes to developing countries including Indonesia, Vietnam and the Philippines. In these countries with limited waste management infrastructure, plastic clogs waterways, putting 218 million people at risk of devastating floods; it pollutes air with toxic fumes when burned, with waste burning causing an estimated 740,000 deaths per year; and it leaches toxic chemicals into the environment.

But it wasn’t the most impacted countries that took center stage at the negotiations. Instead, many countries that profit from fossil fuel and plastics production, including China, India, Saudi Arabia and Iran, delayed progress with procedural debates.

“It was quite evident that it was a power play,” Giulia Carlini, senior attorney at the Center for International Environmental Law, told

Environmental Health News (EHN).

These countries questioned treaty voting rules, opposing a vote by a two-thirds majority of countries in the case that all efforts to reach consensus failed. After three days, a paragraph was added to a meeting report noting the lack of agreement — effectively meaning a vote will not be possible for major treaty decisions unless all countries later agree to one. The treaty is intended to be finalized in 2024.

With other treaties, “the threat of a vote is something that we’ve seen really moving situations that before were stuck in negotiations,” said Carlini. “If there’s no possibility to vote, that will basically give veto power to a few states.”

The delays led to long nights that particularly impacted representatives of low- and middle-income countries, which often have fewer negotiators present, Arpita Bhagat, plastics policy officer at the Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives Asia Pacific, told

EHN. Accommodations near the UNESCO building where negotiations were held were expensive, so some representatives were burdened by travel time. “The meat of the negotiations were happening in the late hours,” Bhagat said.

Despite this road block, many participants were relieved when negotiations moved to substantive matters on Wednesday night. “Many countries expressed their concerns and their interest not only at the downstream, but also at the upstream,” Yuyun Ismawati, co-founder and senior advisor of the Indonesia-based Nexus3 Foundation, told

EHN.

Plastics production is on track to triple by 2060, an unsafe level for human health and the environment,

according to an international panel of scientists. Focusing only on managing plastic waste and not curbing production would fail to address plastics’ harmful lifecycle, as the treaty mandate outlines, Ismawati said.

“People are not able to see beyond plastic as a waste problem versus it being a climate problem caused by the same polluters,” said Bhagat. At the negotiations in Paris, she wore a badge that said “plastics are fossil fuels.”

Bhagat doubts that the initial treaty draft will reflect this, but she’s glad that the week ended with negotiators taking steps to reach a final global plastics treaty.

The next meeting to discuss the initial treaty draft will take place in Nairobi in November. Before then, it’s crucial for the United Nations Environment Program to organize “intersessional work” talks and training sessions that can hammer out technical details before the next meeting, said Bhagat.

Most countries agreed work is needed to determine which plastics and chemical additives are most harmful, which plastics are essential and which pathways are feasible for phasing out unnecessary plastics. Despite that, an agreement on intersessional work wasn’t reached during the week, so it’s unclear if any will take place.

If these information-building meetings do take place, Ismawati is concerned about language accessibility. Intersessional meetings are often held only in English, which can be a barrier to full access for many countries, she explained.

These discussions are most important for countries with low technical and scientific capacity to develop their knowledge on plastic pollution, said Bhagat. “There are a lot of nuances that countries want to get into in order to sufficiently advocate for their own needs for this transition to happen.”

Displaced and distraught: East Palestine remains at risk and without answers

EAST PALESTINE, Ohio — Gary Chirico pulled up to the First Church of Christ in a dust-coated minivan. The grey-bearded building maintenance worker surveyed a wall of boxes, filled with bottles or cans of water.

“Any gallon jugs?” Chirico, 59, asked Mallory Aponick, the church’s disaster relief coordinator.

“I think the gallon jugs are done,” she said.

The choices on this day in late May were plastic bottles or canned water, packaged in cases by Molson Coors.

“I like the aluminum cans,” said Chirico with a grin. “It feels like I’m drinking a beer.”

Chirico spoke like a connoisseur of bottled water — and in the four months since a train derailment forever changed this village of 4,700, his family and many other residents rely on it. A steady stream of vehicles flowed through the church’s back lot. Aponick helped load boxes into them. She said the supply of water on hand — donated by various nonprofits, stacked six feet high and stretched along the back of the building — will probably last three days.

It felt like East Palestine’s rebuke of assurances from authorities that their water, and their town, is safe.

On Feb. 3, a Norfolk Southern train carrying a long list of toxic chemicals — including vinyl chloride and benzene— caught fire as it approached the town. The train derailed and the cars burned for three days.

Some testing done by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has shown levels of toxics that are higher than average and independent researchers insist they are collecting concerning samples around town.

Gov. Mike DeWine’s office, the EPA and the CEO of Norfolk Southern all said that air and water tests detected no signs of toxic chemicals in concentrations that would hurt human health.Boxes of donated bottled or canned water stand beside the First Church of Christ in East Palestine, Ohio.Credit: Nick Keppler for EHNYet residents got sick, they say, reporting headaches, rashes and respiratory problems.Some have not returned out of fear and are living indefinitely with friends, family or in hotels. The divide between how they feel (or how their neighbors feel) and what they’ve been told has deepened their distrust of Norfolk Southern, which is responsible for the cleanup, and the EPA, which is managing the environmental hazard.Months later, the constant movement of trucks and equipment and appearance of mysterious new devices around town still create frustration and confusion. As Norfolk Southern makes promises big and small — vowing to pay to make up for diminished home values and sponsoring the annual street fair — residents don’t know exactly what costs they can bill to the company.For many, the future seems as hazy as it was when plumes of black smoke loomed over their town.

“My stomach hurts. My face hurts. It’s just constant pain”

A sign in East Palestine, Ohio, points towards the free water distribution at the First Church of Christ.Credit: Nick Keppler for EHNChirico grabbed cases of cans. He is staying with his sister-in-law miles away from East Palestine, but he isn’t taking any chances.On Feb. 3, he, his wife and their grandson fled the smoke blowing through their house. His wife developed skin rashes, he said, and he a sore throat. A doctor couldn’t diagnose them with anything but said there was “something bad” in the back of his throat.Before picking up water, Chirico checked on the house. It still has a gas smell, he said. He doesn’t know when they will live there again. “I can’t plant my garden,” he told Environmental Health News (EHN). “The first time in 30 years.” He’s not the only exile.Courtney Miller, a 35-year-old mother of two, told EHN that she left East Palestine in mid-March due to nausea and burning skin. With two bags of belongings, she is staying with a rotation of friends in neighboring counties.“My stomach hurts. My face hurts. It’s just constant pain,” Miller said. Miller immediately distrusted guarantees that the town was safe and rushed to help some independent researchers and right-wing social media figures who descended on the town. She appears in a viral video throwing a rock into a creek and unleashing an oily, rainbow-hued mass. She also collected water samples in the creek. She now thinks she’s paying for that exposure.Rose Tellus, 69, drove by the First Church of Church to pick up another item that’s being offered for free, an air purifier. She hopes it will help in her daughter’s home.Her daughter attempted to return to East Palestine a week after the derailment. “Her skin started burning,” Tellus told EHN, “I had to take her to urgent care. The doctor said, ‘You need to get out of there.’ She had gotten this big blotch on her skin.” She has been staying in a hotel since.

No answers on health concerns

A Norfolk Southern train passes through East Palestine, Ohio.Credit: Nick Keppler for EHNThe EPA can’t answer questions about personal health. A crowd came to a March town hall with questions about their symptoms. Supervisory engineer Mark Durno, the EPA’s representative to the town, told them, “I can’t answer all your questions. I certainly can’t answer your health questions.”The federal agency with that mandate, the Centers for Disease Control, is giving assistance to local health officials, but its presence in town has been less than reassuring. Seven members of its own 15-person team reported getting sick while investigating the derailment. In an email to EHN, DeWine’s press secretary, Dan Tierney, suggested residents take their concerns to the free health clinic opened in February.“While no levels are being detected that would cause short-term or long-term health problems, seeing a physician is the only way to determine if symptoms are related to derailment chemicals or are of health concern,” he wrote.For displaced residents, Norfolk Southern is paying some costs of hotel stays, travel and other expenses. Since February, the company has operated an “assistance center” in a church five miles outside of town, to which residents have frequently schlepped carrying receipts. But as the months pass, along with derailment-related costs, it’s not clear what bills the rail conglomerate will foot.Tellus said that Norfolk Southern has been paying for her daughter’s hotel stay and other expenses. She drained her own savings to pay for professional cleanings of her and her daughter’s homes, plus the removal of carpets and furniture she thinks were contaminated. She said she went to the assistance center to ask about reimbursement. “They said, ‘We’re not there yet.’”In an email to EHN, a company spokesperson wrote that Norfolk Southern “continues to reimburse residents for reasonable expenses related to the derailment through the Family Assistance Center.”He did not respond to a follow up asking what constitutes a “reasonable expense.”

Businesses suffer

Businesses are hurting too.Susan Reynolds, who owns the Dunes Tanning Salon and the Muscle Works Gym, said foot traffic has decreased by 50% at both since the derailment. “My numbers were just heading to where they were pre-Covid,” Reynolds, 58, told EHN while at the front desk of the tanning salon, surrounded by beach-themed decorations. She doesn’t blame customers. Trucks from the clean-up site go past “carrying who knows what,” she said.Rich Kaufman, a longtime employee of Doyle’s Fresh Meat & Deli, said business has been on the decline, particularly from customers who used to come from neighboring towns. “People call and ask if the meat is okay,” he said. “I tell them, ‘We don’t raise it out back.’”Norfolk Southern’s financial obligations will almost inevitably be decided in a class action lawsuit. Each Monday, the town library holds a “Norfolk Southern litigation Q&A.”Some residents struggle to keep up with the pace of changes. Dirt and train parts are hauled out of town. New hazards enter their mind; excavation on the tracks recently kicked up asbestos. New pieces of equipment suddenly show up on the streets and others vanish.“There have been a lot of changes since we first got back and it’s hard to keep up,” Angel Felger, 22, who works at the town’s McDonalds and lives with her mother, told EHN. Felger stopped by the church after her shift to pick up more bottled water.“There were a bunch of things over the drains, like, so water couldn’t get out,” she said. (An EPA representative confirmed that Norfolk Southern installed storm water drain mats to prevent dirt and gravel uprooted by the cleanup from clogging pipes.) “Some people just throw out all their belongings,” she added.

‘It’s like a death pit’: How Ghana became fast fashion’s dumping ground

It’s mid-morning on a sunny day and Yvette Yaa Konadu Tetteh’s arms and legs barely make a splash as she powers along the blue-green waters of the River Volta in Ghana. This is the last leg of a journey that has seen Tetteh cover 450km (280 miles) in 40 days to become the first person known to swim the length of the waterway.It’s an epic mission but with a purpose: to find out whatis in the water and raise awareness of pollution in Ghana.As the 30-year-old swims, a crew shadows her on a solar-powered boat, named The Woman Who Does Not Fear, taking air and water samples along the way that will be analysed to measure pollution.It is hoped that the swim will draw attention to some of the pristine environments in Ghana, in contrast with places such as Korle Lagoon in the capital city of Accra, one of the most polluted water bodies on Earth.“I want people to understand and appreciate the value we have here in Ghana,” says the British-Ghanaian agribusiness entrepreneur. “The only way I can swim is because the waters [of the Volta River] are hopefully clean. Korle Lagoon was once swimmable but now you wouldn’t want to touch any of it.”The swim is supported by the Or Foundation, of which Tetteh is a board member, that campaigns against textile waste in Ghana, one cause of increasing water pollution in the country.Ghana imports about 15m items of secondhand clothing each week, known locally as obroni wawu or “dead white man’s clothes”. In 2021, Ghana imported $214m (£171m) of used clothes, making it the world’s biggest importer.Donated clothes come from countries including the UK, US and China and are sold to exporters and importers who then sell them to vendors in places such as Kantamanto in Accra, one of the world’s largest secondhand clothing markets.Kantamanto is a sprawling complex of thousands of stalls crammed with clothes. You can find items from H&M, Levi Strauss, Tesco, Primark, New Look and more. On display at one stall is a River Island top with a creased cardboard price tag showing that, at one point, it was on sale for £6 in a UK Marie Curie charity shop.As fast fashion – cheap clothes bought and cast aside as trends change – has grown, the volume of clothing coming to the market has increased while the quality has gone down.Jacklyn Ofori Benson is one of about 30,000 people who depend on the market for their livelihood. When the Guardian visits, she is furious. Earlier that morning, when she cut open her bale, she found it full of stained denim shorts.“Today’s bale was very, very costly,” she says. “Most of the 230 items were rubbish; I noticed so many bloodstains. I’m really angry and have thrown all of them away.” To reinforce her point, she picks out other pairs of shorts with broken zips as well as stains that she has kept in the hope of someone buying them for a knockdown price.In another section of the market, people work to repurpose items of clothing that would otherwise be discarded. T-shirts are cut up and sewn together with other bits of material to create skirts, knickers, tops and boxer shorts.John Opoku Agyemang, the secretary of the Kantamanto Hard Workers’ Association, stands at his workstation cutting T-shirts into strips of material that he gives to seamstresses. He exports the resulting garments to other African countries, including Burkina Faso and Ivory Coast.When he first started working at the market 24 years ago, he remembers being able to sell all the clothing that came in a bale. Now, when he opens one, there are about 70 items he can’t use, he says. “The problem of waste is getting worse. For 12 years, the goods coming here have not been good, we can’t benefit from them. It’s my impression that countries abroad think Africa is very poor so they give us low-quality goods and their waste.”According to the Or Foundation, about 40% of the clothing in Kantamanto leaves as waste. Some of it is collected by waste management services, some is burned at the edges of the market, while the rest is dumped in informal landfills.About two miles from the market lies Old Fadama, a once vibrant and thriving community that now resembles an apocalyptic hellscape. It is the largest unsanctioned dump for clothing waste leaving Kantamanto, the Or Foundation believes. The area is home to at least 80,000 people – many have migrated from northern Ghana where the climate crisis is affecting farming; their houses are built on layers of rubbish.Animals graze on metres-high piles of clothes and plastic. A TV lies in the mud. Birds circle overhead while flies swarm close to the ground. Korle Lagoon is here; its waters are black and filled with excrement, its shores lined with litter. The air is hazy with smoke from fires burning waste. Rubbish collectors pick up plastic bottles, put them into sacks and carry them on their heads. No one smiles.It wasn’t always like this. Alhassan Fatawu, a 24-year-old photographer, moved to Old Fadama as a child with his mother and remembers swimming in the lagoon and playing on its shores. “As it is now, I can’t go near the lagoon. It’s like a death pit. People used to fish there, there were a lot of canoes with people depending on the lagoon for their livelihood.”He adds: “The last decade was mad [in terms of waste being dumped there] … It’s so upsetting.”Korle Lagoon leads to the ocean. Waste is washed out to sea before some of it ends up lining the beaches of Accra. In Jamestown, one beach, next to a huge port development financed by China, is hemmed in by cliffs, which have clothes hanging off them. You can’t walk out into the waves without stepping over mounds of clothes and plastic waste.At one end of the beach, Thomas Alotey sits on a boat mending fishing nets. He is resigned to his surroundings. “We want the situation to change but nothing will happen,” he says. “I know some of the clothes come from abroad but it is Ghana’s responsibility to dispose of the waste properly.”He adds: “We are suffering. When I go out to fish, I come back with more clothes in my nets than fish.”About 80 miles to the east, where Tetteh started the final leg of her swim, the scene could not be more different. The water is clean and enticing; the banks of the river are lined with palm trees and sandy beaches, and there’s only the odd canoe for company.“There are parts that have been just sublime,” says Tetteh of her journey. “We came across small, sandy islands surrounded by super-calm, still waters against brilliant blue skies. The vistas are incredible.”The crew’s journey has not been without challenges, however. There were nights spent on stormy waters in the middle of Lake Volta, the world’s largest artificial reservoir, because the boat ran out of power; tsetse flies, known to cause the potentially fatal sleeping sickness, hovered ominously round the crew; the boat got stuck in mud and it took the four-person crew along with a team of fishers three hours getting it afloat; and strong currents and lively waves made swimming almost impossible at times.But, just before 6pm on 17 May as the sun set and the sky took on hues of orange, yellow and red, Tetteh swam towards the shore in Ada, where the River Volta meets the Atlantic Ocean. A crowd gathered to cheer her on and welcome her. She walked out of the water to a soundtrack of traditional drumming, and was flanked by a pair of dancers who accompanied her as she was greeted by community elders. Ghanaian TV crews had come to capture her, and the crew’s, triumph.“It’s extremely satisfying to have finished,” says Tetteh. “I was very excited when I could taste salt in the water. Before that, I thought I wasn’t going to make it.”

US lead pipe replacements stoke concerns about plastic and environmental injustice

Roughly 9.2 million lead pipes deliver drinking water to homes, schools and other buildings in the U.S., according to an Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) estimate released last month.

The Biden administration has announced its intention to replace all lead service lines within 10 years; and in 2021, Congress made $15 billion available for lead service line replacement through the bipartisan infrastructure law that passed last year. The EPA estimates the average cost to replace a lead service line is $4,700, putting the total need at $43 billion.

Scientists and drinking-water advocates say this fund is only a starting-point. A 2020 EPA analysis failed to consider many health outcomes from lead exposure, causing some experts to fear there’s a lack of willingness at the agency to address the problem. This could change, with new regulations on lead exposure expected from the EPA in September 2023. Advocates say upcoming rules need to include a mandate and funding for utilities to fully replace lead service lines so everyone can benefit from the program, including low-income customers.

Complicating lead pipe replacement are alternatives that may carry health risks of their own. A new report from Beyond Plastics, the Plastic Pollution Coalition and Environmental Health Sciences highlights a growing body of research that has found toxic chemicals in PVC and CPVC pipes — commonly used to replace lead lines — that have the potential to leach into drinking water. Health advocates say that in replacing lead lines, cities and states need to select safe materials to avoid a regrettable substitution, and many say copper is the best option. (Environmental Health Sciences publishes Environmental Health News, which is editorially independent.)

The EPA has chosen not to regulate plastic pipes or look into their potential health effects, Judith Enck, president of Beyond Plastics and former EPA regional administrator, told Environmental Health News (EHN).

“We’ve had about a half a dozen meetings with EPA, and every office we meet with points to another office,” she said, “It’s a lot of buck passing.”

Lack of federal motivation on lead replacement

The EPA enforces the Lead and Copper Rule, which requires utilities to address contamination when more than 10% of customer taps have high levels of lead or copper. Credit: Enoch Appiah Jr./UnsplashLead was a common material for service lines, the pipes that connect a building to a water main, until Congress banned them in 1986 due to health risks. There is no safe level of lead exposure, the EPA says. In children, lead affects growth, behavior, IQ and more. Lead can impact pregnancies, causing early births and damage to a baby’s brain, kidneys and nervous system. In adults, lead can impact cardiovascular health, kidney function and fertility. Research has found that minority and low-income households are more likely to face lead exposure, often because their homes were built during the decades when lead service lines were most prevalent.The EPA enforces the Lead and Copper Rule, which requires utilities to address contamination when more than 10% of customer taps have high levels of lead or copper. The Trump administration revised the rule, adding new testing requirements and protocols intended to require more action from utilities to reduce lead exposure. When the agency released their economic analysis of the rule revisions, “I was appalled,” Ronnie Levin, instructor at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and former EPA senior scientist, told EHN. The EPA recognizes eight health outcomes caused by lead, and eight that are likely caused by lead. “They only monetized one,” Levin said. Related: Check out Beyond Plastics’ “The Perils of PVC Plastic Pipes” reportThat means they didn’t quantify many health outcomes the rule revisions would improve by lowering lead exposure. With the single health outcome monetized, the EPA analysis found roughly $160 to $330 million in costs from the revisions, and $230 to $800 million in benefits. “EPA considered both the quantifiable and the nonquantifiable health risk reduction benefits in promulgating the final Lead and Copper Rule…EPA exercised discretion to determine the approaches used to quantify benefits,” a spokesperson for the EPA told EHN in an email. Levin ran the numbers herself, including as many EPA acknowledged health outcomes from lead as she could. In a non-peer-reviewed preprint study, she and a coauthor estimate $9 billion in health benefits and an additional $2 to $8 billion in savings on plumbing materials thanks to corrosion control required by the Lead and Copper Rule revisions. The EPA’s underestimation of benefits demonstrates a lack of investment to address lead in drinking water, Levin said. “EPA, when it really wants to do something, loads on all the benefits it can marshal.” She’s concerned the incomplete health benefits analysis means the agency isn’t committed to solving this problem.

Environmental injustice and lead replacement

A young girl at the “Poor People’s Campaign” in Washington DC in 2018. A study in Washington D.C. found that low-income neighborhoods were far less likely to receive full service lead line replacements. Credit: Susan Melkisethian/flickrUnder the Biden administration, the Lead and Copper Rule will see another set of changes, which the EPA plans to announce in September 2023. The agency told an appeals court in December 2022 that it expects to require replacement of all lead service lines in that rulemaking.Some utilities are ahead of the curve, and have used funds from last year’s infrastructure act and other sources to jump start lead service line replacement. “But until we actually get a requirement that those lead pipes are pulled out, we’re concerned that a lot of communities are just going to shrug their shoulders,” Erik Olson, attorney and senior strategic director of the NRDC’s Health and Food, People & Communities Program, told EHN. To access state funds, utilities have to hire consulting firms to put together proposals for lead service line replacement, Olson explained. Low-income communities with fewer resources might not have the capacity to access the programs available now, but could be motivated with better funding and a mandate to replace service lines. Currently, the EPA is rolling out a technical assistance program in four states — Connecticut, New Jersey, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin — to help disadvantaged communities access funds. “We’re hoping that EPA will require the full replacement and at the expense of the utility, because otherwise we’re just not going to see a solution to this problem and it really will be an environmental injustice,” Olson said. When lead service lines are replaced by utilities, the Lead and Copper Rule requires them to address the portion they own. But that ownership is up for debate: many utilities say the property owner owns part of the service line, and that the utility is only responsible for a portion of it. Olson said utilities have been unable to provide documentation to back up this claim when asked by NRDC. Still some cities, including Washington D.C., have required customers to pay for a portion of a lead service line replacement, generally costing a few thousand dollars. A study of this program in Washington D.C. found that low-income neighborhoods were far less likely to receive full service line replacements. Neighborhoods with more Black residents were also less likely to receive full replacements. Instead, in many places the utility performed partial replacements, leaving some lead pipe intact. These partial replacements “may be worse than doing nothing,” the study said. The partial replacement process can disturb pipe coatings and speed up corrosion, leading to higher lead contamination of water. For example, research on partial lead service line replacements in Halifax, Canada,, found that a partial replacement more than doubled lead release in the short term, and had no beneficial effects on lead contamination after six months. In 2019, Washington D.C.’s council changed their program to better fund full replacements and address past partial replacements. “EPA strongly discourages water systems from conducting partial lead service line replacement,” said the EPA spokesperson.

PVC piping health impacts

[embedded content]The material that goes in to replace lead pipes can also create health concerns. Common replacements for lead service lines include pipes made from copper and plastics such as high-density polyethylene, polyvinyl chloride (PVC) and chlorinated polyvinyl chloride (CPVC). Plastic pipes tend to be the cheapest option, but a report last month highlights serious health risks from plastic PVC and CPVC pipes. Scientists have identified 59 chemicals that can leach from PVC pipes, but there’s a dearth of research on exactly what concentrations could be found in home tap water and what health risks they pose. The report shows that some toxics leach from plastic pipes, including vinyl chloride, a known carcinogen, and phthalates and organotins, endocrine-disruptors that impact the body’s hormone system.Plastic pipes, particularly PVC and CPVC, could represent a regrettable substitution for lead pipes, said Enck in a press conference about the report. “EPA does not have requirements for plumbing materials beyond the requirements for lead-free,” Senior Communications Advisor for EPA, Dominique Joseph, told EHN in an email. “EPA has supported the development of independent, third-party testing standards for plumbing materials under NSF/ANSI 61, which has been incorporated into many state and local plumbing codes.” The report raises concerns about the rigor of the NSF/ANSI 61 standard, which was developed by NSF International, an industry-funded organization. Beyond concerns for chemical leaching into drinking water, “Plastic pipes are an environmental justice issue,” Enck said. The vinyl chloride that makes the pipes is largely produced in the Gulf Coast and Appalachia, where surrounding communities face exposure to the carcinogen. Vinyl chloride was the principal chemical released in the February train derailment in East Palestine, Ohio. The train was also carrying PVC pellets on their way to a PVC pipe manufacturer, said Mike Schade, director of Mind the Store at Toxic-Free Future, at a press conference for the report.Copper can also corrode from pipes and cause health issues in high concentrations, but this is less common than high lead levels, and can be managed with corrosion control, said NRDC’s Olson. Recycled copper is the best choice for service lines to protect public health, the report concludes.

Cities take action on lead pipes

Plastic pipes, particularly PVC and CPVC, could represent a regrettable substitution for lead pipes. Credit: Unsplash+Some cities have made drinking water exposures a priority, and set an example for others to follow, Olson said. He points to Newark, New Jersey, which replaced more than 20,000 lead service lines with copper at no expense to property owners within a few years.Somerville, Massachusetts, is replacing all of its non-copper service lines with copper, prioritizing lead pipe removals first. “Copper tubing is the preferred water service material as it is sturdier and has a longer life span,” Karla Cuarezma, project manager for Somerville, said in an email to EHN. Troy, New York, also plans to replace lead pipes with copper. This pipe material preference has been in the city’s code for many decades, and they’re planning to stick with it, Chris Wheland, Troy’s superintendent of public utilities, told EHN. He added that at high water pressures plastic pipes don’t last as long. After facing criticisms for a slow start to the lead service line replacement program, Troy is putting a $500,000 fund to work to identify lead service line locations and begin some replacements. But Wheland said this is only a start, Troy will need $30 million to finish the job and replace all of its lead service lines. “We also have many other programs that we have to fund,” he said, “I still have to maintain the water plant, I still have to maintain pipes to the water plant and out of the water plant, because if I don’t have a water plant to give you water, there’s no sense in worrying about the lead pipe.”

EPA spurns Trump-era effort to drop clean-air protections for plastic waste recycling

Reversing its own Trump-era proposal, the Environmental Protection Agency has spurned a lobbying effort by the chemical industry to relax clean-air regulations on two types of chemical or “advanced” recycling of plastics.

The decision, announced by the EPA on May 24, covers pyrolysis and gasification, two processes that use chemical methods to break down plastic waste. Both have largely been regulated as incineration for nearly three decades and have therefore had to meet stringent emission requirements for burning solid waste under the federal Clean Air Act.

But in the final months of the Trump administration, the EPA proposed an industry-friendly rule change in August 2020 stating that pyrolysis does not involve enough oxygen to constitute combustion, and that emissions from the process should therefore not be regulated as incineration.

Pyrolysis, or the process of decomposing materials at high temperatures in an oxygen-free environment, has been around for centuries. Traditional uses have ranged from making tar from timber for wooden ships to transforming coal into coke for steelmaking.

Today, the chemical industry is looking to pyrolysis as a way to convert plastic waste into synthetic gases, char residue, and a type of oil that can then be turned into fuel or chemical feedstocks. (Gasification is similar to pyrolysis but uses some oxygen.)

Proponents argue that pyrolysis works with plastics that are otherwise difficult to recycle, providing an alternative to typical mechanical methods like shredding, melting and remolding the waste into new products. The industry has marshaled such arguments in lobbying state legislatures across the country to pass laws that incentivize the development of a chemical recycling industry for plastics.

The world is making twice as much plastic waste as it did two decades ago, with most of the discarded material buried in landfills, burned in incinerators or dumped into the environment, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, a forum for developed nations.

Annual production of plastic is expected to triple by 2060 to 1.23 billion metric tons yearly, with OECD countries like the U.S. producing far more per person than their counterparts in Africa and Asia. Only 9 percent of plastic waste is successfully recycled, the organization reports.

Responding to growing concern, the chemical industry has championed what it calls advanced recycling. But government scientists have questioned the supposed environmental benefits of the chemical recycling of plastic waste as well as the technology’s commercial viability, at least in the short term.

Democratic Lawmakers Prevailed

The EPA’s 2020 proposal to ease its rules, which was related to how the agency regulates municipal waste combustion units, drew sharp criticism from environmentalists and Democrats in Congress. They argued that pyrolysis and gasification were indeed a form of combustion—and that abandoning strict regulation of those processes in chemical recycling would present health risks while failing to address the plastic waste crisis.

“Instead of leading to the recovery of plastic and supporting the transition to a circular economy, pyrolysis and gasification lead to the release of more harmful pollutants and greenhouse gases,” 35 lawmakers wrote the EPA last summer. They urged the agency to fully regulate the emissions from chemical recycling as waste combustion and to cease efforts to promote the technology as a solution to the global plastics crisis.

Among those signing the letter were the House Democrats Jamie Raskin of Maryland and Jared Huffman of California, the Democratic senators Edward Markey of Massachusetts and Cory Booker of New Jersey, and Sen. Bernie Sanders of Vermont, an independent. “Chemical recycling contributes to our growing climate crisis and leads to toxic air emissions that disproportionately impact vulnerable communities,” the legislators wrote.

In a new fact sheet posted on the EPA’s website, the agency noted that it had “received significant adverse comments” on the provision it had put forward during the Trump administration. In taking final action to withdraw the proposal, the agency said it would “prevent any regulatory gaps and ensure that public health protections are maintained.”

In a notice to be published in the Federal Register, the EPA left the door open to changing its mind later. It said it has received 170 comments on the 2020 proposal and that it was “evident that pyrolysis is a complex process that is starting to be used in many and varied industries.” The agency said it would need significant time and personnel to analyze the comments and other information to gain a full understanding of pyrolysis.

The American Chemistry Council, a lobbying group that is working to advance policies that promote chemical recycling, did not immediately respond to a request for comment. But last summer, Joshua Baca, vice president for plastics at the council, said that the regulatory changes were necessary.

“The appropriate regulation of this is really critical if you want to scale advanced recycling, and you want to use more recycled material in your products,” Baca said.

The lobbying group has also helped persuade 24 states, most recently Indiana in April, to pass legislation recognizing advanced recycling as manufacturing rather than waste management, another path toward easing regulation of the fledgling industry.

Environmental advocates celebrated the EPA’s decision, saying it would help their groups and local communities fight for cleaner air amid the expansion of chemical recycling.

Keep Environmental Journalism AliveICN provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going.Donate Now

As plastics keep piling up, can ‘advanced’ recycling cut the waste?

Bob Powell had spent more than a decade in the energy industry when he turned his attention to the problem of plastic waste. “I’m very passionate about the environment,” he says. To him, the accumulating scourge of irresponsibly discarded plastic ranks high on the list of environmental issues, “right behind global warming and drought.” In 2014, he found what he considers a solution: a suite of technologies that uses chemicals and heat to turn plastic into oil to manufacture more plastic.

In the years since, Powell founded a “plastics renewal” company, Brightmark, Inc., whose first plant, currently in its start-up phase, has processed 2,000 tons of waste plastic at its Circularity Center in Ashley, Indiana. Using an “advanced plastics recycling” technique called pyrolysis, post-consumer plastics delivered to the Brightmark plant are subjected to intense heat in an oxygen-starved environment until their molecules shake apart, yielding a type of oil similar to plastic’s petroleum feedstock, along with some waste byproducts. Ideally, Powell says, Brightmark will sell the oil to produce new plastic, promoting true circularity in the manufacturing supply chain.

Around the world, companies are drawing up plans for pyrolysis plants, promising relief from the crushing problem of plastic pollution. Small startups and demonstration projects are joining with larger companies, including petroleum and chemical giants. Chevron Phillips was recently awarded a patent for its proprietary pyrolysis process, and ExxonMobil announced in March it was considering opening pyrolysis plants in Baton Rouge, Louisiana; Beaumont, Texas; and Joliet, Illinois. ExxonMobil already operates a pyrolysis facility in Baytown, Texas, which the company claims will recycle 500,000 tons of plastic waste annually by 2026.

“There’s a lack of transparency about how much plastic they’re recycling” and what the end product will be used for, a critic says.

Globally, the market for advanced recycling technologies is projected to exceed $9 billion by 2031, up from $270 million in 2022, according to a report from Research and Markets, an industry analysis firm. That’s a 32 percent increase every one of those nine years.

Proponents of pyrolysis say it will keep plastic out of landfills, incinerators, and waterways, prevent it from choking marine life, and keep its toxic components from leaching into soil and contaminating water and air. The American Chemistry Council says that “advanced recycling reduces greenhouse gas emissions 43 percent relative to waste-to-energy incineration of plastic films made from virgin resources.”

Subscribe to the E360 Newsletter for weekly updates delivered to your inbox. Sign Up.