Since the start of the 2020s, humanity has faced worldwide calamity after worldwide calamity, all of them raising questions about our survival as a species. The COVID-19 pandemic has already claimed millions of lives and not yet finished its rampage. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has raised the specter of nuclear holocaust, which many assumed has subsided with the end of the Cold War. Even as these problems worsen, climate change continues to quietly creep along in the background, overheating the planet for future generations.

Yet what if, on top of all these things, there is an even more dystopian crisis in the offing — one in which humans are no longer able to reproduce without artificial help because we have filled the environment with chemicals that have altered our bodies?

Scientists believe this is not only possible, it is likely to happen within our lifetimes.

Understanding why involves three statistics: First, that a human male who has fewer than 15 million sperm per milliliter is considered infertile; second, that in the 1970s sperm counts in Western countries (where there is available data) showed an average of 99 million sperm per milliliter; and third, that this number had dropped to 47 million sperm per milliliter by 2011. Scientists agree that plastic pollution is a likely culprit.

The trailblazer here has been Dr. Shanna Swan, a professor of environmental medicine and public health at Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York City, whose most famous book has a conveniently self-explanatory title: “Count Down: How Our Modern World Is Threatening Sperm Counts, Altering Male and Female Reproductive Development, and Imperiling the Future of the Human Race.”

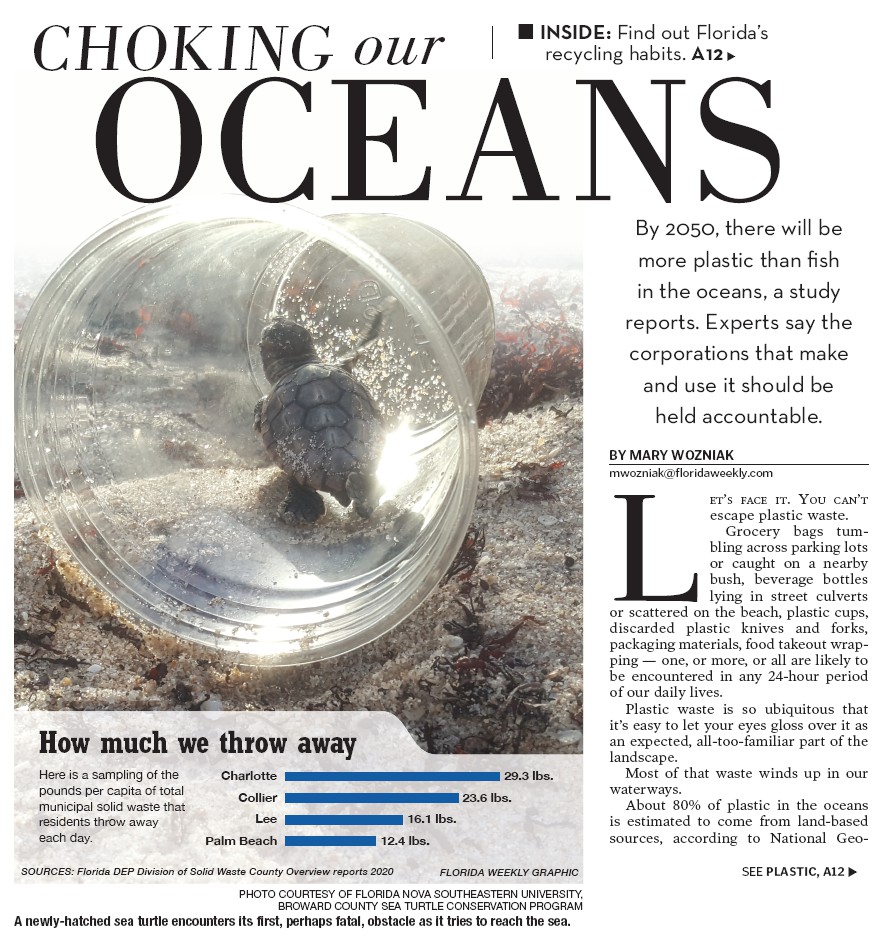

The main culprit is believed to be chemicals within everyday plastics known as endocrine disruptors. These chemicals, including a range of phthalates and bisphenols, are literally inescapable. They can be found in the dishware, food cans and containers from which you eat your food, and in the water bottles and other plastic receptacles from which you drink. They are in virtually all of your commonly used household electronics, your eyeglass lenses, your furniture and even on any commercial receipts that come from a thermal printer. Because endocrine disruptors are in pesticides, they have also entered the foods that we eat thanks to the agriculture industry. Even without pesticides, though, we would still wind up eating these endocrine disruptors. Microplastics — that is, plastic particles which are five millimeters or less across or in length — have entirely covered the planet. Animals accidentally eat microplastics all the time and plants regularly absorb them through their roots. Humans themselves ingest the rough equivalent of a credit card’s worth of plastic each week.

Want more health and science stories in your inbox? Subscribe to Salon’s weekly newsletter The Vulgar Scientist.

“First society needs to identify and agree we have a very serious problem; this takes time like climate change,” Bjorn Beeler, international coordination at IPEN — International Pollutants Elimination Network — told Salon by email. “Scientists knew in the 1970s/80s climate change was coming due to [greenhouse gas] emissions, and now we are discussing adaptation and climate crisis 40+ years later (late). So to curb the threat, we need to define the problem, then turn off the toxic chemical tap.”

Even if that happens, however, there is so much plastic everywhere that humanity simply cannot escape at least some of the consequences from this constant exposure. Swan told Salon by email that federally funded assisted reproduction technology — something currently provided in only one country, Israel — will help in making sure that people impacted by this pollution can still have children.

“Disadvantaged communities are more highly exposed to risky chemicals and they are more affected (on average) by the same level of exposure,” Swan wrote to Salon. “So, it’s a ‘triple whammy’ for these communities.”

John Hocevar, the Oceans Campaign Director for Greenpeace USA, explained to Salon by email that “reduced sperm counts and other reproductive ailments disproportionately impact low income communities and people of color. Poor communities are more likely to be located closest to incinerators and landfills, as well as refineries. Access to expensive treatments to compensate for reproductive health issues are not equitable today, and even with an optimistic view of the US political landscape it is clear that this problem is not going to go away any time soon.”

Not surprisingly, the plastic industry and others that rely on these chemicals dispute that the endocrine disruptors are responsible for the drop in sperm counts. As Beeler pointed out, they will provide alternate data just like industries do when they dispute the validity of climate science. Hocevar added that plastic companies also have an advantage because plastics are so pervasive that “it is difficult to design controls where plastic can be excluded as a factor. The plastic industry uses this terrible situation to try to claim that we don’t have enough evidence to be sure that these chemicals are dangerous.”

And, to be clear, there are other factors that no doubt contribute to fertility issues for both men and women: Obesity, smoking, binge drinking, stress. Still, the science about endocrine disruptors is clear.

“Chemicals in plastic (phthalates, bisphenols and others) as well as pesticides, lead and other environmental exposures are linked to impaired reproduction including sperm count and quality,” Swan told Salon. “Some, like phthalates and BPA, have a short half-life in the body (4-6 hours), so it is possible to reduce the body’s exposure if we can stop using products containing these.” At the same time, society will have to exercise collective will and make sure that the most vulnerable among us are not left behind.

“Low-income communities can’t afford to ‘buy their way out’ of the problem by purchasing organic, unprocessed foods, safer cosmetics etc. (which are more expensive),” Swan explained. “But the ‘mass infertility scenario’ is a threat to everyone (not just the disadvantaged).”

Read more on plastic pollution: