A Scots Tory MSP has hit out after the SNP Government admitted it had no idea how many of Scotland’s 19,000 wind turbines may be releasing dangerous chemicals. There have been concerns for years about the environmental impact from the erosion of microplastics from the colossal turbine blades, which are made with fibreglass and epoxy …

Category Archives: News

2022’s top ocean news stories

Marine scientists from the University of California, Santa Barbara, share their list of the top 10 ocean news stories from 2022.Hopeful developments this past year include the launch of negotiations on the world’s first legally binding international treaty to curb plastic pollution, a multilateral agreement to ban harmful fisheries subsidies and a massive expansion of global shark protections.At the same time, the climate crises in the ocean continued to worsen, with a number of record-breaking marine heat waves and an accelerated thinning of ice sheets that could severely exacerbate sea level rise, underscoring the need for urgent ocean-climate actions.This post is a commentary. The views expressed are those of the authors, not necessarily Mongabay. 1. Negotiations for historic global plastics treaty break ground

Global leaders cheered to the strike of a recycled-plastic gavel in March, signifying a landmark decision by the United Nations Environment Assembly to create the first-ever legally binding international treaty to curb plastic pollution. With 8.3 billion metric tons of plastic having been produced to date, the decision marks a historic moment in addressing one of our blue planet’s greatest crises.

Negotiations for the global plastics treaty began in November in Uruguay, where representatives from more than 150 countries came together to start discussing details and goals. This International Negotiating Committee (INC) aims to finalize a formal treaty in a series of upcoming meetings by the end of 2024.

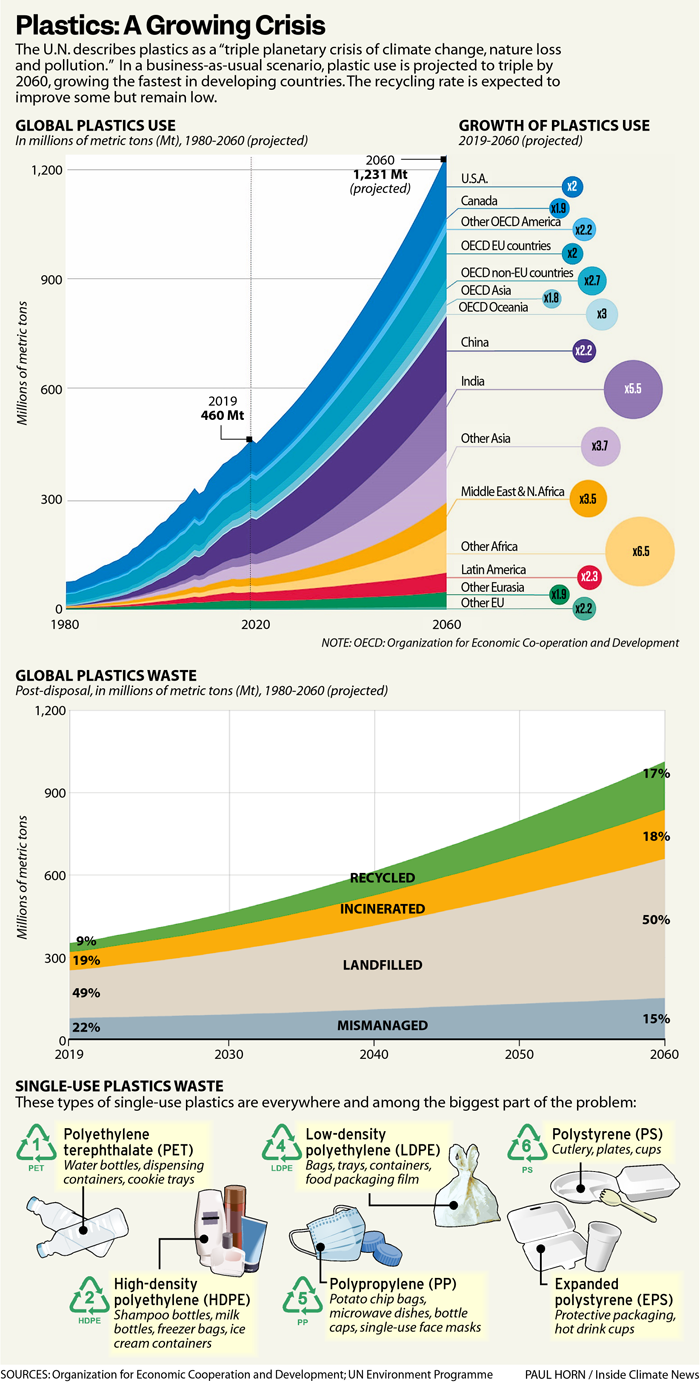

Without major efforts to reduce plastic pollution, projections show that 12 billion metric tons of plastic waste could end up in the natural environment or landfills by 2050. Plastic accounts for 85% of marine debris already, and the volume of plastic in the ocean may triple by 2040. Some groups are working to curb this pollution by capturing plastic waste in river mouths before it enters the sea. The Clean Currents Coalition, a global cleanup network facilitated by our team at the Benioff Ocean Science Laboratory at the University of California Santa Barbara, has collected nearly 1,000 metric tons of plastic from rivers in eight countries. However, it’s going to take more than a few trash wheels to solve the problem.

Recycling is also not the entire answer, at least as currently implemented. Of all the plastic ever produced, only 9% has been recycled. Ultimately, it seems we need to reduce our global dependence on this substance, and a legally binding international agreement that operates across the entire supply chain is an essential first step.

Without major efforts to reduce plastic pollution, projections show that 12 billion metric tons of plastic waste could end up in the natural environment or landfills by 2050. Image by Lucien Wanda via Pexels (Public domain).

2. Sea level rise

One of the primary drivers of sea level rise is the thawing of global ice. A study published in November provided some bleak news from Greenland’s largest ice sheet, suggesting that it is thawing at an accelerated rate and will add six times more water to the ocean than scientists previously thought. The calculations show that by the end of this century, it will add 0.5 inches to the global ocean level, an amount equal to Greenland’s overall contribution to sea level rise over the past 50 years.

Scientists are closely monitoring the Thwaites Glacier in Antarctica, also known as the “Doomsday” glacier, as a new study shows it is capable of shrinking faster than it has in recent years. The glacier is the size of Florida and accounts for about 5% of Antarctica’s contribution to changes in global sea level; if it were to collapse into the ocean, it could cause a rapid rise in sea levels. Focusing on just the United States, NASA released a study in October showing the average level of sea rise for the majority of coastlines in the contiguous United States could reach 30 centimeters (12 inches) by 2050.

The analysis draws on almost three decades of satellite data, and the results could help coastal communities prepare adaptation plans for the coming years, which may bring an increase in flooding. The estimated waterline increase will vary regionally: 25-36 cm (10-14 in) for the East Coast, 36-46 cm (14-18 in) for the Gulf Coast and 10-20 cm (4-8 in) for the West Coast. Experts cite climate change as a leading cause of the sea level rise, along with natural factors, such as El Niño and La Niña events and the moon’s orbit.

Calculations show that by the end of this century, Greenland’s melting ice will add 0.5 inches to the global ocean level. Image by Marek Okon via Unsplash (Public domain).

3. A major milestone in shark and ray protection

In November, governments from around the world came together at the 19th Conference of the Parties (CoP19) to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) in a massive showing of leadership to increase the protection of nearly 100 species of sharks & rays. CoP19 parties voted to list 54 species of requiem sharks, six species of hammerhead sharks and 37 species of guitarfish under CITES Appendix II.

The designation limits international trade and grants greater protection to these species, many of which are threatened with extinction by the unsustainable global trade in their fins and meat. This is a huge win for shark conservation as it brings 90% of the internationally traded shark species under CITES protection. Previously only 20% had been protected. International trade of these species will only be permitted if they are not endangered as a result, and will require an export permit to ensure that legal and sustainable trade is taking place.

The proposals were championed by Panama, the host country, and co-sponsored by more than 40 other CITES-party governments. It is one of 46 proposals that was adopted by the delegation at the conference and reaffirms international commitments to protect both terrestrial and marine species that are impacted by the global wildlife trade. In addition to the nearly 100 species of sharks and rays, the parties voted to increase the protection of 150 tree species, 160 amphibian species, 50 turtle and tortoise species and several species of songbirds.

In November, governments from around the world came together at the CITES COP19 to increase the protection of nearly 100 species of sharks and rays. Image by Matt Waters via Pexels (Public domain).

4. Momentum builds for a global moratorium on seabed mining

2022 marked a dramatic change in what previously appeared to be an almost inevitable march toward the start of the controversial emerging industry of deep-sea mining. Marine policy experts deemed that the “two-year rule” triggered by Nauru in 2021 had unclear legal footing and implementation, undercutting efforts to see seabed mining start as soon as July 2023 under whatever regulations are in place at the time.

Scientists this year also came together to highlight substantial scientific gaps in our understanding of the environmental impacts of seabed mining. Countries, businesses and scientists also united in strengthening a call for a global moratorium, or pause, on seabed mining. In a major shifting of political winds at the June-July UN Ocean Conference in Lisbon, Pacific states, including Palau, Fiji, Samoa and the Federated States of Micronesia, led an alliance calling for a moratorium. France later became the first nation to call for a complete ban on the activity. Twelve nations have now taken formal positions against deep-sea mining in international waters this year.

Amid this growing opposition, the International Seabed Authority approved its first mining trials since the 1970s. These commenced in September in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone, an area beyond national jurisdictions in the Pacific Ocean that contains rare-earth elements and metals. In November, a new report suggested that seabed minerals may not be necessary at all and that their demand could instead be met by recycling and existing terrestrial reserves.

The deep-sea mining vessel Hidden Gem moored in the Waalhaven port of Rotterdam in 2021. Twelve nations have now taken formal positions against deep-sea mining in international waters this year. Image © Marten van Dijl / Greenpeace.

5. Asia-Pacific ocean leadership

The Asia-Pacific region is home to the most biologically diverse and productive marine ecosystems. The countries in this region are also characterized by having a larger population and stronger economic growth than any other region. And yet many global conversations calling for increased ambition in ocean leadership have historically lacked Asia-Pacific representation. 2022 suggested a turning of that tide. The G20, hosted this year in Indonesia, included an entire summit, the O20, devoted to ocean health issues. There appears to be nascent interest in carrying this leadership tradition forward at the next G20 summit, to be hosted in September by India. Similarly, Japan will host the G7 summit in Hiroshima next May and has engaged in discussions to elevate the UN’s Sustainable Development Goal 14, which deals with the ocean, as a major topic.

With the rising threat of climate change, countries in the Asia-Pacific region have turned their attention this year to blue carbon. China, which lost more than half of its mangrove swamps between 1950 and 2001, is making some initial progress in protecting its marine ecosystem by creating an international mangrove center, national standards for coral reef restoration and its first comprehensive methodology for blue carbon accounting. At COP27, the UN climate conference that took place in November in Sharm El Sheikh, Egypt, the establishment of the International Blue Carbon Institute was announced. The institute will serve as a knowledge hub to develop and scale blue carbon projects. It will be housed in Singapore to focus on supporting Southeast Asia and the Pacific Islands.

Indonesia has taken action to slow the loss of its mangroves, the world’s largest collection, through multiple initiatives such as launching the Mangrove Alliance for Climate. This slow but steady emerging leadership in oceans by countries in the Asia-Pacific region is a promising sign.

The Asia-Pacific region is home to the most biologically diverse and productive marine ecosystems. Image by Kanenori via Pixabay (Public domain).

6. Outer space ocean

Oceans may not be as exclusive to Earth as we previously thought. A new study reveals that 4.5 billion years ago Mars had enough water to be covered in an ocean as deep as 300 meters (nearly 1,000 feet). The Mars that we know in the present day is a reddish color and averages temperatures of negative 62 degrees Celsius (negative 80 degrees Fahrenheit), making it unable to support water in any form other than ice. During the first 100 million years of Mars’ evolution, ice-filled asteroids that carried organic molecules crashed on the planet, allowing for conditions supportive of life to emerge long before they did on Earth.

Because Mars does not have plate tectonics, the surface preserves a historical record of the planet’s history; researchers were able to gain insight into the red planet’s wetter past, as well as into the formation of the solar system, from a meteorite found on Earth that was part of Mars’ original crust billions of years ago.

NASA’s Curiosity Mars rover. A new study reveals that 4.5 billion years ago Mars had enough water to be covered in an ocean. Image by NASA/JPL-Caltech/MSSS.

7. Ocean giants

This year brought both ups and downs for the world’s largest charismatic marine megafauna: whales. Scientists are looking into what is causing a 40% decline in birth rates of the Pacific gray whale (Eschrichtius robustus) population that travels along the U.S. West Coast on its migration from Baja, Mexico, back to the Arctic. This past year’s decline brings the birth rate to the lowest level since 1994. The scarcity of food sources in their Arctic feeding grounds due to climate change is one main factor scientists say they believe is contributing to the decline.

Another study showed that blue, fin and humpback whales feed at 50-250 meters (164-820 feet) below the surface, which coincides with the ocean’s highest concentrations of microplastics. The authors estimated that blues ingest 10 million pieces per day. Some progress was made on mitigating one of the largest threats to large whales: ship strikes.

The waters off the southern coast of Sri Lanka are important blue whale habitat for feeding and nursing, but also a busy shipping lane that creates a high risk for fatal collisions. The largest container line in the world has started ordering its ships to slow down in this region and travel outside the known whale habitat, helping to reduce the risk of collisions by 95%. The tech-driven platform Whale Safe (one of our projects at the Benioff Ocean Science Laboratory), designed to prevent whale-ship collisions and piloted in southern California, was replicated and deployed in the San Francisco region, helping to create a safer environment for whales off the U.S. West Coast.

A study showed that blue, fin and humpback whales feed at 50-250 meters (164-820 feet) below the surface, which coincides with the ocean’s highest concentrations of microplastics. Image by ArtTower via Pixabay (Public domain).

8. Explosive interest in blue carbon

Climate change continues to be the biggest threat facing our ocean and planet. 2022 brought a happy but belated influx of investment and attention to blue carbon, a term that refers to using mangroves, tidal marshes, seagrass beds, and other marine ecosystems to sequester carbon dioxide in the fight against climate change.

Mangroves have the potential to store up to 10 times as much carbon as tropical rainforests. In addition to the pivotal role they might have in preventing climate change, blue carbon ecosystems also protect coastal communities from flooding and storms and provide habitat for marine life. As a result, protecting these marine ecosystems was a key topic at COP27, a focus of research by academic institutes and an area of investment by companies such as Google and Salesforce (whose co-founder, Marc Benioff, also funds the Benioff Ocean Science Laboratory, where we work).

Australia’s national science agency, CSIRO, and Google announced a $2.7 million blue carbon AI research project that will help researchers understand blue carbon ecosystems in the Indo-Pacific and Australia. At COP27, Salesforce, the World Economic Forum’s Friends of Ocean Action and a global coalition of ocean leaders announced the High-Quality Blue Carbon Principles and Guidance, a blue carbon framework to guide the development and purchasing of high-quality blue carbon projects and credits. In the last decade alone, the oceans have absorbed about 23% of carbon dioxide emitted by human activities and investment in their protection and recovery will be vital to the overall fight against climate change.

Mangroves have the potential to store up to 10 times as much carbon as tropical rainforests. Image by Rhett A. Butler/Mongabay.

9. Marine heat waves and coral reefs

Record-breaking heat events took place across the globe this year, and not just on land. Rising ocean temperatures are a cause for concern because they increase stress on already vulnerable ecosystems like coral reefs. The sea surface temperatures over the northern part of the Great Barrier Reef were the warmest November temperatures on record, raising fears this may be the second summer in a row of a massive coral bleaching event that affected 91% of surveyed reefs last year.

The news isn’t all bad, though. Innovative finance mechanisms are being leveraged to protect coral reefs from these threats. In Hawai’i, The Nature Conservancy purchased an insurance policy to protect the state’s reefs from hurricanes and tropical storms. If wind speeds reach 50 knots (57.5 mph) or more, the policy will pay out, allowing for rapid reef repair. This is the first policy of its kind in the U.S., although similar approaches have been used in Mexico, Belize, Guatemala and Honduras. Creative finance solutions like this will continue to be a key component of protecting these vital ecosystems.

The sea surface temperatures over the northern part of the Great Barrier Reef were the warmest November temperatures on record. Image by Rhett A. Butler/Mongabay.

10. A decisive year for the ocean

2022 was a big year for ocean policies, marked by a number of breakthroughs by the international community, some of which had been long-awaited after pandemic-induced delays. Major themes addressed reducing plastic pollution, protecting marine biodiversity, supporting the blue economy, decarbonizing shipping and more. Key policy moments included a landmark deal to ban harmful fishing subsidies that was reached after 20 years of negotiations at the World Trade Organization. The historic agreement specifically prohibits subsidies to illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing and to fisheries targeting overexploited fish stocks. At the UN Ocean Conference, member states made more than 700 conservation commitments pledging to expand marine protected areas, end destructive fishing practices, increase investments and expand blue economies.

More than 100 nations have affirmed voluntary commitments to protect 30% of their oceans by 2030. At the conference, the Protecting Our Planet Challenge announced it will invest at least $1 billion to support this goal. Several countries also announced plans to create and expand marine protected areas, including Colombia, which, if it fully implements its plan, would become the first country to achieve the 30% goal ahead of the 2030 target.

In November, the Green Shipping Challenge launched at COP27, with more than 40 announcements by countries, ports, and companies detailing measures to decarbonize shipping, an industry that currently emits close to 3% of global greenhouse gas emissions. Many of the announcements were related to green shipping corridors and technological developments for climate-neutral ships, such as innovative propulsion systems, sailing cargo ships and the production of low- and zero-emission fuels.

Finally, to cap off 2022, after two years of delay from the pandemic, the UN conference on the Convention on Biological Diversity (COP15) took place in Montreal. Early on the morning of Dec. 19, delegates reached a historic new global biodiversity agreement that outlines 23 conservation targets to prevent biodiversity loss over the next decade, including protecting 30% of land, fresh water and the ocean by 2030. During negotiations, there were strong disagreements among delegates about how much funding was needed to reach these goals and who should pay for it. In the final agreement, nations collectively committed to spending $200 billion per year on biodiversity conservation.

Callie Leiphardt is a project scientist at the Benioff Ocean Initiative, where she works on projects to develop science- and technology-based solutions to ocean problems, such as the Whale Safe project to reduce fatal whale-ship collisions along the California coast. Her background is in conservation planning, particularly with marine mammals. Douglas McCauley is an associate professor at the University of California, Santa Barbara, and director of the Benioff Ocean Science Laboratory. Neil Nathan is a project scientist at Benioff Ocean Science Laboratory, where he works on issues such as deep-sea mining, marine protected areas in the high seas and shark monitoring using drones and artificial intelligence. Nathan has a background in natural capital approaches, which aim to incorporate the value of ecosystem services into decision-making and planning. Rachel Rhodes is a project scientist at the Benioff Ocean Science Laboratory, where she works on Whale Safe. Her background is in marine geospatial data and strategic environmental communications. Aaron Roan leads technology and engineering initiatives across projects at the Benioff Ocean Science Laboratory. He comes from Google and Slack and has spent more than a decade using technology, machine learning and data to help with ocean science and conservation.

Banner image: A whale shark swimming with remoras in Ras Mohammed National Park, Egypt. Image by Cinzia Osele Bismarck / Ocean Image Bank.

Citations:

Geyer, Roland, Jenna R. Jambeck, and Kara Lavender Law. “Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made.” Science Advances 3.7 (2017). doi:10.1126/sciadv.1700782.

Khan, S. A., Choi, Y., Morlighem, M., Rignot, E., Helm, V., Humbert, A., … Bjørk, A. A. (2022). Extensive inland thinning and speed-up of Northeast Greenland ice stream. Nature, 611(7937), 727-732. doi:10.1038/s41586-022-05301-z

Graham, A. G., Wåhlin, A., Hogan, K. A., Nitsche, F. O., Heywood, K. J., Totten, R. L., … Larter, R. D. (2022). Rapid retreat of thwaites glacier in the pre-satellite era. Nature Geoscience, 15(9), 706-713. doi:10.1038/s41561-022-01019-9.

Hamlington, Benjamin D., et al. “Observation-based trajectory of future sea level for the coastal United States tracks near high-end model projections.” Communications Earth & Environment 3.1 (2022). doi:s43247-022-00537-z.

Amon, Diva J., et al. “Assessment of scientific gaps related to the effective environmental management of deep-seabed mining.” Marine Policy 138 (2022). doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2022.105006.

Zhu, Ke, et al. “Late delivery of exotic chromium to the crust of Mars by water-rich carbonaceous asteroids.” Science Advances 8.46 (2022). doi:eabp8415.

Kahane-Rapport, S. R., Czapanskiy, M. F., Fahlbusch, J. A., Friedlaender, A. S., Calambokidis, J., Hazen, E. L., … Savoca, M. S. (2022). Field measurements reveal exposure risk to microplastic ingestion by filter-feeding megafauna. Nature Communications, 13(1). doi:10.1038/s41467-022-33334-5

Wylie, Lindsay, Ariana E. Sutton-Grier, and Amber Moore. “Keys to successful blue carbon projects: lessons learned from global case studies.” Marine Policy 65 (2016). doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2015.12.020

FEEDBACK: Use this form to send a message to the editor of this post. If you want to post a public comment, you can do that at the bottom of the page.

Adaptation To Climate Change, Biodiversity, Climate Change, Climate Change And Conservation, Climate Change And Coral Reefs, Climate Change Policy, Coastal Ecosystems, Commentary, Conservation, Endangered Species, Environment, Environmental Law, Environmental Policy, Environmental Politics, Fish, Fishing, Governance, Impact Of Climate Change, Mangroves, Marine, Marine Animals, Marine Biodiversity, Marine Conservation, Marine Crisis, Marine Ecosystems, Marine Protected Areas, Ocean Crisis, Ocean Warming, Oceans, Oceans And Climate Change, Saltwater Fish, Sea Levels, Wildlife, Wildlife Conservation

Print

These 'floating garbage bins' are mitigating ocean pollution by capturing tons of marine litter

Plastic pollution is among the most pressing environmental issues given the rapid increase of disposable plastic products over the past decade. Every year, about 8 million tons of plastic waste escapes into the oceans from coastal nations, and forecasts suggest this could double by 2025 if drastic action is not taken.

1. Seabin project

Seabin Project is a clean tech startup on an ambitious mission to help solve the global problem of ocean plastic pollution and ocean conservation. Andrew Turton and Pete Ceglinski launched Seabin Project in Australia, back in 2015, to extract plastic from the ocean. As part of the project, floating “seabins” were installed to skim plastics and other debris from harbour water before they can reach the ocean — a key preventive solution previously identified by scientists and conservationists, including the National Geographic Society.

Each bin can capture 90,000 plastic bags a year. Learn more: https://t.co/ZZX0Masf50@Seabin_project pic.twitter.com/o3xjEixIKQ— World Economic Forum (@wef) September 23, 2022

“We are now in the 6.0 (next generation technology), which includes smart technology, water sensors and a modem for cloud-based or IoT connectivity,” said CEO and co-founder Ceglinski, explaining how their commercial product acts as a floating garbage bin and intercepts trash, oil, fuel and detergents. Data estimates suggest their technology with each Seabin allows them to capture 90,000 plastic bags every year for less than $1 a day. The collected debris is then recycled or sent to a waste management facility.

2. Capturing marine litter

The Seabin Project is accelerating its global expansion with the “100 cities by 2050” campaign, selecting Marina Del Rey in Los Angeles as the second city after Sydney, Australia. From July 2020 to November 2022, the project captured 100 tons of marine litter in Sydney, while in Los Angeles, 2.1 tons were captured between July 2022 to November 2022. The city choices weren’t random as the team believes the world’s marinas and ports are the perfect places to start helping clean the oceans.

With no huge open ocean swells or storms inside the marinas, these relatively controlled environments provide the perfect locations for Seabin installations. The Seabin Project

3. A severe problem

Most of the plastic trash in the oceans flows from land. Trash is also carried to sea by major rivers, which act as conveyor belts, picking up more and more trash as they move downstream. The problem increases when plastics break down into microplastics moving freely through water and air. Plastics often contain additives making them stronger, more flexible, and durable. But many of these additives also extend the life of products when they become litter, with some estimates ranging to at least 400 years to break down.

© Seabin Project

Poonam Watine, Knowledge Specialist at the World Economic Forum’s Global Plastic Action Partnership, believes that innovative solutions like the Seabin can prove to be a significant step in the right direction to mitigate and prevent plastic pollution.

“High impact and inspiring trailblazers like Seabin provide a glimmer of hope on how to take action to the impending plastic crisis through alternative solutions,” said Watine.

New US lawsuit targets ‘forever chemicals’ in plastic food containers

New US lawsuit targets ‘forever chemicals’ in plastic food containers Suit alleges Inhance failed to follow EPA rules involving dangerous PFAS chemicals and asks a judge to halt production A new lawsuit says many plastic containers used in the US to hold food, cleaning supplies, personal care items and other consumer products are likely to …

Continue reading “New US lawsuit targets ‘forever chemicals’ in plastic food containers”

Five ways sequins add to plastic pollution

Getty ImagesBy Navin Singh KhadkaEnvironment correspondent, BBC World ServiceChristmas and New Year are party time – an occasion to buy a sparkling new outfit. But clothes with sequins are an environmental hazard, experts say, for more than one reason.1 Sequins fall off”I don’t know if you’ve ever worn anything with sequins, but I have, and those things are constantly falling off, especially if the clothes are from a fast-fashion or discount retailer,” says Jane Patton, campaigns manager for plastics and petrochemicals with the Centre for International Environmental Law.”They come off when you hug someone, or get in and out of the car, or even just as you walk or dance. They also come off in the wash.”The problem is the same as with glitter. Both are generally made of plastic with a metallic reflective coating. Once they go down the drain they will remain in the environment for centuries, possibly fragmenting into smaller pieces over time.”Because sequins are synthetic and made out of a material that almost certainly contains toxic chemicals, wherever they end up – air, water, soil – is potentially dangerous,” says Jane Patton.”Microplastics are a pervasive, monumental problem. Because they’re so small and move so easily, they’re impossible to just clean up or contain.”Researchers revealed this year that microplastics had even been found in fresh Antarctic snow.Biodegradable sequins have been invented but are not yet mass-produced.2 Party clothes – the ultimate throwaway fashionThe charity Oxfam surveyed 2,000 British women aged 18 to 55 in 2019, 40% of whom said they would buy a sequined piece of clothing for the festive season.Only a quarter were sure they would wear it again, and on average respondents said they would wear the clothing five times before casting it aside.Five per cent said they would put their clothes in the bin once they had finished with them, leading Oxfam to calculate that 1.7 million pieces of 2019’s festive partywear would end up in landfill.Once in landfill, plastic sequins will remain there indefinitely – but studies have found that the liquid waste that leaches out of landfill sites also contains microplastics.One group of researchers said their study provided evidence that “landfill isn’t the final sink of plastics, but a potential source of microplastics”.Getty Images3 Unsold clothes may be dumpedViola Wohlgemuth, circular economy and toxics manager for Greenpeace Germany, says 40% of items produced by the clothing industry are never sold. These may then be shipped to other countries and dumped, she says. Clothes decorated with sequins are, inevitably, among these shipments. Viola Wohlgemuth says she has seen them at second-hand markets and landfill sites in Kenya and Tanzania.”There’s no regulation for textile waste exports. Such exports are disguised as second-hand textiles and dumped in poor countries, where they end up in landfill sites or waterways, and they pollute,” she says.”It is not banned as a problem substance like other types of waste, such as electronic or plastic waste, under the Basel Convention.” 4 There is waste when sequins are madeSequins are punched out of plastic sheets, and what remains has to be disposed of.”A few years ago, some companies tried to burn the waste in their incinerators,” says Jignesh Jagani, a textile factory owner in the Indian state of Gujarat.”And that produced toxic smoke, and the state’s pollution control board came to know of it and made the companies stop doing that. Handling such waste is indeed a challenge.”One of the developers of compostable cellulose sequins, Elissa Brunato, has said she began by making sheets of material that the sequins were then cut out of. To avoid this problem, she moved to making sequins in individual moulds.High microplastic concentration found on ocean floorBiodegradable litter backed by Sir David AttenboroughWashed clothing’s synthetic mountain of ‘fluff’5 Sequins are attached to synthetic fibresThe problem is not only the sequins, but the synthetic materials they are usually sewn on to.According to the UN Environment Programme, about 60% of material made into clothing is plastic, such as polyester or acrylic, and every time the clothes are washed they shed tiny plastic microfibres.These fibres find their way into waterways, and from there into the food chain.According to one estimate from the International Union for Conservation of Nature, synthetic textiles are responsible for 35% of microfibres released into the oceans. George Harding of the Changing Markets Foundation, which aims to tackle sustainability problems using the power of the market, says the fashion industry’s use of plastic sequins and fibres (derived from oil or gas) also demonstrates a “deeply rooted reliance on the fossil fuel industry for raw materials”.He adds that clothing production is predicted to almost double by 2030, compared with 2015 levels, so “the problem is likely to only get worse without significant interventions”.

The Capitol Christmas tree provides a timely reminder on environmental stewardship this holiday season

WASHINGTON—A ceremony on the Capitol’s West Lawn to light a 78-foot red spruce from Pisgah National Forest earlier this month heralded the festive holiday season. The tree was one of nearly 5 million Christmas trees harvested in North Carolina this year.

“Our Capitol Christmas tree reminds us of the importance of working together to be good stewards of our environment, so that future generations can enjoy the bounties of forests and Christmases still to come,” said Republican Sen. Richard Burr of North Carolina.

The tree will light up the West Lawn until the first week of January, when its wood will be recycled to make musical instruments, according to the U.S. Forest Service. These instruments will be donated to local North Carolina communities.

The tree’s afterlife as newly crafted violins, guitars and mandolins demonstrates one of several sustainable ways to dispose of Christmas trees—a key issue for increasingly climate-conscious consumers weighing the choice between real and artificial trees.

A survey conducted by the National Christmas Tree Association estimated that almost 21 million trees were purchased in the U.S. in 2021. Around 10 million artificial trees are reported to be purchased each season.

The growth of the artificial tree market has had an acute impact on growers with consumer preferences shifting towards artificial trees over the past 30 years, said Jill Sidebottom of the National Christmas Tree Association.

The reason for the shift is likely multi-faceted. The Association’s survey found that the median price of a real tree in 2021 was $69.50. Higher costs of production and constrained supply means this will likely increase this year, according to a New York Times analysis. The shortage in supply can be partially attributed to planting decisions made a decade ago, the newspaper said. Trees must grow for five to 15 years before they are ready to be harvested.

Artificial trees, which also retailed at a median price of $70 in 2021, may also become more expensive as production and transport costs increase globally. However, these can be re-used for many years, making them more affordable in the long run.

A comparison between real and artificial trees has left some consumers concerned about the sustainability of purchasing real trees. The debate is a nuanced one. Real trees capture and store carbon during their lifetime. However, once cut down for Christmas, their potential to harm the environment depends on those who buy and dispose of them.

According to Ian Rotherham, emeritus professor at Sheffield Hallam University in England and a researcher on wildlife and environmental issues, the comparison must involve more than just the act of cutting down trees.

“If you’re cutting down a Christmas tree from a mixed-age plantation, where you take some of the trees out and you leave some in, that actually has no impact on the carbon capture of that plantation because the trees will compensate relative to the space that you’ve freed up,” he said.

Harvesting a large number of trees that are the same size and age at once will have some impact. However, “they will probably then replant another crop into that same space … So, to some extent that will balance, so long as you are then disposing of the tree when you have used it in a responsible way,” he said.

For every Christmas tree harvested in the U.S., one to three seedlings are planted the following spring, according to the National Christmas Tree Association.

The best option for the environment, in Rotherham’s view, “depends on what you do with it after you’ve used them.”

A real tree that is dumped in a landfill will produce methane as it decomposes. Methane is a greenhouse gas that has more than 80 times the warming power of carbon dioxide over the first 20 years after it reaches the atmosphere. While carbon dioxide has a longer-lasting effect on the climate, methane drives the speed of warming in the near term.

The methane produced by a two-meter tree as it decomposes is equivalent to emitting 16 kilograms of carbon dioxide, according to Carbon Trust, a U.K.-based nonprofit focused on climate change and carbon emissions. If all 21 million U.S. consumers who purchased a real Christmas tree last year disposed of it in landfill, the climate impacts would be the equivalent of 42,283 homes’ energy use for one year, according to an analysis using EPA data.

Keep Environmental Journalism AliveICN provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going.Donate Now

Is ‘chemical recycling’ a solution to the global scourge of plastic waste or an environmentally dirty ruse to keep production high?

Diplomats negotiating guidelines for an international convention on hazardous wastes this month in Switzerland debated a new section on the “chemical recycling” of plastic debris fouling the global environment.

The 1989 Basel Convention, which seeks to protect human health and the environment against the adverse effects of hazardous wastes, was updated in 2019 when 187 ratifying nations agreed to place new restrictions on the management and international movement of plastic wastes—and to update the treaty’s technical guidelines.

Since then, the plastics industry has tried to quell mounting anger over vast mountains of plastics filling landfills and polluting the oceans by advancing chemical recycling as a means of turning discarded plastic products into new plastic feedstocks and fossil fuels like diesel.

Scientists and environmentalists who have studied the largely unproven technology say it is essentially another form of incineration that requires vast stores of energy, has questionable climate benefits, and puts communities and the environment at risk from toxic pollution. Some of them even view the inclusion of the chemical recycling language in the implementing guidelines as a threat, although it remains to be seen what that language will ultimately say.

“The text is nowhere near settled,” said Sirine Rached, the global plastics policy coordinator for the Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives (GAIA), which with the Basel Action Network has called chemical recycling of plastics “a fantasy beast that has yet to establish its efficacy and economic viability, while already exhibiting serious environmental threats.”

Rached said the group’s “priority is for the guidance to focus on environmentally-sound management and to refer to technologies only on the basis of sound peer-reviewed references, and not on industry marketing claims, and this involves not speculating on how technologies may or may not evolve in future.”

“The solution is making less plastic,” Judith Enck, founder and president of the environmental group Beyond Plastics and a former EPA regional administrator, told a subcommittee of the Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works at a hearing on Dec. 15.

U.S. lawmakers are weighing their own ideas for addressing the plastics crisis. “We need to cut plastic production by 50 percent in the next 10 years, and we can do it,” she told them, adding that chemical recycling produces “more fossil fuel and the last thing we need is more fossil fuel.”

Such a dramatic cut in plastic would devastate the economy, said Matt Seaholm, chief executive officer of the Plastics Industry Association, which represents companies that produce, use and recycle plastic. “Our industry wants to recycle more,” and deploying more mechanical recycling and chemical recycling will help, he told lawmakers. “We love plastic,” he said. “We hate the waste. We need to collect, sort and ultimately reprocess more material.”

Wide agreement exists that the 11 million metric tons of plastic pollution that enters the oceans every year “is devastating,” Erin Simon, head of plastic waste and business for the World Wildlife Fund, a conservation group that operates in 100 countries, said in an interview. “It’s wreaking havoc on our species, our ecosystems and in the communities that depend on them.

“You really do need this coordinated global structure” that treaties can provide, she added. “Because it’s clear that it’s not going to happen just with voluntary initiatives alone.”

Writing Guidelines for Chemical Recycling

The world is making twice as much plastic waste as it did two decades ago, with most of the discarded materials buried in landfills, burned by incinerators or dumped into the environment, according to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, a group that represents developed nations. Production is expected to triple by 2060. Globally, only 9 percent of plastic waste is successfully recycled, according to OECD.

Nearly all of the plastic that gets recycled goes through a mechanical process involving sorting, grinding, cleaning, melting and remolding, often into other products. But mechanical recycling has its limits; it does not work for most kinds of plastic and what gets recycled, such as certain kinds of bottles and jugs, can only be recycled a few times.

Chemical recycling consists of new and old technologies, hailed by the industry but seen as an unproven marketing ruse by environmentalists, that governments must now study and regulate if they are to successfully confront a menacing problem that spans the Earth and has even invaded our bodies with microplastic particles.

A Basel Convention committee met in the second week of December in Switzerland to debate whether the Basel treaty’s technical guidelines should be updated to include chemical recycling, which is also sometimes referred to as “advanced recycling,” and if so, under what terms.

The debate occurred within the framework of the Basel Convention and any language on chemical recycling that makes it into its technical guidelines will be seen as acceptable tools for managing plastic waste. The guidelines are likely to carry over into the negotiations over the next two years on an international treaty governing plastic pollution and ongoing plastics manufacturing.

Those treaty talks have barely begun, with a first negotiation session among delegates a few weeks ago in Uruguay.

The technical guidelines for the Basel Convention are supposed to represent the best available technology for protecting humans from various hazardous wastes, said Lee Bell, an Australia-based policy advisor for the International Pollutants Elimination Network (IPEN). He is also the co-author of a 2021 IPEN study that detailed how chemical recycling generates dangerous dioxin emissions, produces contaminated fuels and consumes large amounts of energy.

“Many parties and observers are of the view that there is no proof that chemical recycling is what you would call best available technology … or best environmental practice,” he said.

The concern, he said, is that chemical recycling’s inclusion in the technical guidance “becomes a sort of formal endorsement by the (Basel) convention, and therefore by the U.N.”

It then would be possible for advocates of chemical recycling to point to the Basel technical guidance and say, “‘let’s just adopt those wholesale as part of the new plastics treaty,’” Bell said. “And I think this is exactly what’s going on.”

Stewart Harris, senior director of global plastics policy for the American Chemistry Council, said it’s too soon to say what role chemical recycling might play in a global plastics agreement. But, he said, the Basel Convention technical guidance is important.

“The Basel Convention guidance on the environmentally sound management of plastic waste is a key resource for all countries looking to support the transition to a more circular economy for plastics,” Harris said. “Properly classifying chemical recycling will help governments assess how these technologies fit into national waste management plans.”

In a joint release with the International Council of Chemical Associations following the first round of plastics treaty talks, held Nov. 28 to Dec. 2 in Uruguay, the two industry groups favored an agreement that “moves nations closer to a future where plastics remain in the economy and not in the environment.”

Industry opposes caps on soaring plastic production, which Enck and other environmentalists say is the only way to ultimately solve the environmental crisis that is plastic waste and pollution.

Judith Enck, founder and president of the environmental group Beyond Plastics, speaking at a Bennington College seminar in August. Credit: James Bruggers

In the United States, the fight over chemical recycling has occurred in statehouses, local communities, in Congress and inside the Environmental Protection Agency. The American Chemistry Council, a leading industry advocate for chemical recycling, this year celebrated adoption of legislation by 20 states over the past five years aimed at easing regulatory pathways for chemical recycling.

“The appropriate regulation of this is really critical if you want to scale advanced recycling, and you want to use more recycled material in your products,” Joshua Baca, vice president of plastics for the chemistry council, told Inside Climate News.

But plastics were never designed to be recycled, and environmental advocates have been fighting back, trying to block new chemical recycling facilities that have been proposed in various states across the country.

In Pennsylvania, a Houston start-up called Encina has proposed a $1.1 billion chemical recycling plant for plastic waste in Point Township that has left local officials and professors at Pittsburgh universities perplexed about whether the company’s plans were at all feasible. Nearby residents, meanwhile, worried about impacts to air, water and quality of life.

In northeast Indiana, Inside Climate News found Brightmark Energy struggling to get its chemical recycling facility, using a technology called pyrolysis, up and running. The company could not precisely say what percentage of plastic waste it would actually turn into fuel or plastic feedstocks.

Jay Schabel, president of the plastics division at Brightmark, stood amid some of what he described as 900 tons of waste plastic at the company’s new plant in northeast Indiana at the end of July. The plant is designed to turn plastic waste into diesel fuel, naphtha and wax. Credit: James Bruggers

And while Fulcrum BioEnergy does not market its waste-to-jet fuel plant proposed for Gary, Indiana, as chemical recycling, it would employ a similar technical process, gasification. Inside Climate News found that the company’s plans to use municipal solid waste are complicated by an anticipated 30 percent plastic in its feedstock, which reduces carbon benefits and can gum up the production process. In Gary, an environmental justice community, residents have filed a Civil Rights Act complaint with the EPA against the state regulators who approved the Fulcrum air permit.

“Technologies that worsen the climate crisis, perpetuate a reliance on single-use plastics, and adversely impact vulnerable communities cannot be viewed as viable solutions moving forward,” a group of 35 members of Congress wrote in July, urging the EPA to fully regulate chemical recycling emissions and to stop working to promote the technology as a solution to the plastics crisis.

A Global Solution

Plastic waste is a global problem and the countries of the world are working on a global solution.

In March, against the backdrop of what U.N. officials described as a “triple planetary crisis of climate change, nature loss and pollution,” the United Nations Environmental Assembly voted to start two years of negotiations for a treaty to end global plastic waste.

Keep Environmental Journalism AliveICN provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going.Donate Now

Is ‘chemical recycling’ a solution to the global scourge of plastic waste or an environmentally dirty ruse to keep production high?

Diplomats negotiating guidelines for an international convention on hazardous wastes this month in Switzerland debated a new section on the “chemical recycling” of plastic debris fouling the global environment.

The 1989 Basel Convention, which seeks to protect human health and the environment against the adverse effects of hazardous wastes, was updated in 2019 when 187 ratifying nations agreed to place new restrictions on the management and international movement of plastic wastes—and to update the treaty’s technical guidelines.

Since then, the plastics industry has tried to quell mounting anger over vast mountains of plastics filling landfills and polluting the oceans by advancing chemical recycling as a means of turning discarded plastic products into new plastic feedstocks and fossil fuels like diesel.

Scientists and environmentalists who have studied the largely unproven technology say it is essentially another form of incineration that requires vast stores of energy, has questionable climate benefits, and puts communities and the environment at risk from toxic pollution. Some of them even view the inclusion of the chemical recycling language in the implementing guidelines as a threat, although it remains to be seen what that language will ultimately say.

“The text is nowhere near settled,” said Sirine Rached, the global plastics policy coordinator for the Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives (GAIA), which with the Basel Action Network has called chemical recycling of plastics “a fantasy beast that has yet to establish its efficacy and economic viability, while already exhibiting serious environmental threats.”

Rached said the group’s “priority is for the guidance to focus on environmentally-sound management and to refer to technologies only on the basis of sound peer-reviewed references, and not on industry marketing claims, and this involves not speculating on how technologies may or may not evolve in future.”

“The solution is making less plastic,” Judith Enck, founder and president of the environmental group Beyond Plastics and a former EPA regional administrator, told a subcommittee of the Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works at a hearing on Dec. 15.

U.S. lawmakers are weighing their own ideas for addressing the plastics crisis. “We need to cut plastic production by 50 percent in the next 10 years, and we can do it,” she told them, adding that chemical recycling produces “more fossil fuel and the last thing we need is more fossil fuel.”

Such a dramatic cut in plastic would devastate the economy, said Matt Seaholm, chief executive officer of the Plastics Industry Association, which represents companies that produce, use and recycle plastic. “Our industry wants to recycle more,” and deploying more mechanical recycling and chemical recycling will help, he told lawmakers. “We love plastic,” he said. “We hate the waste. We need to collect, sort and ultimately reprocess more material.”

Wide agreement exists that the 11 million metric tons of plastic pollution that enters the oceans every year “is devastating,” Erin Simon, head of plastic waste and business for the World Wildlife Fund, a conservation group that operates in 100 countries, said in an interview. “It’s wreaking havoc on our species, our ecosystems and in the communities that depend on them.

“You really do need this coordinated global structure” that treaties can provide, she added. “Because it’s clear that it’s not going to happen just with voluntary initiatives alone.”

Writing Guidelines for Chemical Recycling

The world is making twice as much plastic waste as it did two decades ago, with most of the discarded materials buried in landfills, burned by incinerators or dumped into the environment, according to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, a group that represents developed nations. Production is expected to triple by 2060. Globally, only 9 percent of plastic waste is successfully recycled, according to OECD.

Nearly all of the plastic that gets recycled goes through a mechanical process involving sorting, grinding, cleaning, melting and remolding, often into other products. But mechanical recycling has its limits; it does not work for most kinds of plastic and what gets recycled, such as certain kinds of bottles and jugs, can only be recycled a few times.

Chemical recycling consists of new and old technologies, hailed by the industry but seen as an unproven marketing ruse by environmentalists, that governments must now study and regulate if they are to successfully confront a menacing problem that spans the Earth and has even invaded our bodies with microplastic particles.

A Basel Convention committee met in the second week of December in Switzerland to debate whether the Basel treaty’s technical guidelines should be updated to include chemical recycling, which is also sometimes referred to as “advanced recycling,” and if so, under what terms.

The debate occurred within the framework of the Basel Convention and any language on chemical recycling that makes it into its technical guidelines will be seen as acceptable tools for managing plastic waste. The guidelines are likely to carry over into the negotiations over the next two years on an international treaty governing plastic pollution and ongoing plastics manufacturing.

Those treaty talks have barely begun, with a first negotiation session among delegates a few weeks ago in Uruguay.

The technical guidelines for the Basel Convention are supposed to represent the best available technology for protecting humans from various hazardous wastes, said Lee Bell, an Australia-based policy advisor for the International Pollutants Elimination Network (IPEN). He is also the co-author of a 2021 IPEN study that detailed how chemical recycling generates dangerous dioxin emissions, produces contaminated fuels and consumes large amounts of energy.

“Many parties and observers are of the view that there is no proof that chemical recycling is what you would call best available technology … or best environmental practice,” he said.

The concern, he said, is that chemical recycling’s inclusion in the technical guidance “becomes a sort of formal endorsement by the (Basel) convention, and therefore by the U.N.”

It then would be possible for advocates of chemical recycling to point to the Basel technical guidance and say, “‘let’s just adopt those wholesale as part of the new plastics treaty,’” Bell said. “And I think this is exactly what’s going on.”

Stewart Harris, senior director of global plastics policy for the American Chemistry Council, said it’s too soon to say what role chemical recycling might play in a global plastics agreement. But, he said, the Basel Convention technical guidance is important.

“The Basel Convention guidance on the environmentally sound management of plastic waste is a key resource for all countries looking to support the transition to a more circular economy for plastics,” Harris said. “Properly classifying chemical recycling will help governments assess how these technologies fit into national waste management plans.”

In a joint release with the International Council of Chemical Associations following the first round of plastics treaty talks, held Nov. 28 to Dec. 2 in Uruguay, the two industry groups favored an agreement that “moves nations closer to a future where plastics remain in the economy and not in the environment.”

Industry opposes caps on soaring plastic production, which Enck and other environmentalists say is the only way to ultimately solve the environmental crisis that is plastic waste and pollution.

Judith Enck, founder and president of the environmental group Beyond Plastics, speaking at a Bennington College seminar in August. Credit: James Bruggers

In the United States, the fight over chemical recycling has occurred in statehouses, local communities, in Congress and inside the Environmental Protection Agency. The American Chemistry Council, a leading industry advocate for chemical recycling, this year celebrated adoption of legislation by 20 states over the past five years aimed at easing regulatory pathways for chemical recycling.

“The appropriate regulation of this is really critical if you want to scale advanced recycling, and you want to use more recycled material in your products,” Joshua Baca, vice president of plastics for the chemistry council, told Inside Climate News.

But plastics were never designed to be recycled, and environmental advocates have been fighting back, trying to block new chemical recycling facilities that have been proposed in various states across the country.

In Pennsylvania, a Houston start-up called Encina has proposed a $1.1 billion chemical recycling plant for plastic waste in Point Township that has left local officials and professors at Pittsburgh universities perplexed about whether the company’s plans were at all feasible. Nearby residents, meanwhile, worried about impacts to air, water and quality of life.

In northeast Indiana, Inside Climate News found Brightmark Energy struggling to get its chemical recycling facility, using a technology called pyrolysis, up and running. The company could not precisely say what percentage of plastic waste it would actually turn into fuel or plastic feedstocks.

Jay Schabel, president of the plastics division at Brightmark, stood amid some of what he described as 900 tons of waste plastic at the company’s new plant in northeast Indiana at the end of July. The plant is designed to turn plastic waste into diesel fuel, naphtha and wax. Credit: James Bruggers

And while Fulcrum BioEnergy does not market its waste-to-jet fuel plant proposed for Gary, Indiana, as chemical recycling, it would employ a similar technical process, gasification. Inside Climate News found that the company’s plans to use municipal solid waste are complicated by an anticipated 30 percent plastic in its feedstock, which reduces carbon benefits and can gum up the production process. In Gary, an environmental justice community, residents have filed a Civil Rights Act complaint with the EPA against the state regulators who approved the Fulcrum air permit.

“Technologies that worsen the climate crisis, perpetuate a reliance on single-use plastics, and adversely impact vulnerable communities cannot be viewed as viable solutions moving forward,” a group of 35 members of Congress wrote in July, urging the EPA to fully regulate chemical recycling emissions and to stop working to promote the technology as a solution to the plastics crisis.

A Global Solution

Plastic waste is a global problem and the countries of the world are working on a global solution.

In March, against the backdrop of what U.N. officials described as a “triple planetary crisis of climate change, nature loss and pollution,” the United Nations Environmental Assembly voted to start two years of negotiations for a treaty to end global plastic waste.

Keep Environmental Journalism AliveICN provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going.Donate Now

Guatemala landfill feeds ‘trash islands’ hundreds of miles away in Honduras

An estimated 20,000 metric tons of trash from the Guatemala City landfill flows down the Motagua River into the Caribbean each year, where it washes ashore on Honduran beaches and forces residents to form cleanup efforts.While cleanup efforts are a good temporary solution, the root cause of the problem is poor waste management infrastructure at the landfill, something that has proven extremely difficult to address due to complex social issues and the cost of relocating waste disposal sites to other parts of the country.The trash also comes from illegal dumping along the river.As a stopgap, some stakeholders are focused on catching the trash in the rivers before it can reach the ocean. GUATEMALA CITY — After heavy rains, hotel workers and other residents in Honduras walk up and down beaches picking up everything from plastic bottles to toys to medical waste. They’ve become experts at garbage cleanup. It piles up in the sand if they don’t move quickly, and then tourists might complain or even stop coming, which could be disastrous for the many residents who rely on work in local hotels and shops.

Some towns on Honduras’s Caribbean coast have banned single-use plastics and implemented more rigorous recycling plans. But the trash keeps coming. A lot of it, it turns out, doesn’t come from the locals, but rather from landfills and illegal dumping sites hundreds of miles away, in inland Honduras and neighboring Guatemala.

“It goes into the food chain and even disrupts coral,” says Jenny Myton, the conservation program director at the Coral Reef Alliance. “This affects everything — animal life and health, but also the economy and tourism.”

Guatemala’s 485-kilometrer (300-mile) Motagua River is one of the biggest conduits of this torrent of waste. An estimated 20,000 metric tons of trash from the Guatemala City landfill and illegal dumping sites flows into the river on its way to the Caribbean each year. Ocean currents push it northeast, where it washes up on the beaches of Tela and other Honduran towns. The rest of it can stay floating out at sea for as long as six months before sinking to the bottom.

The problem has elicited cleanup efforts, recycling programs and garbage divergence plans by everyone from local communities to international NGOs. But many of them also admit that these are only temporary solutions. The root cause of the problem — garbage collection and storage at landfills across the region — will be much harder to make right.

“A new waste management plan must be set up for Guatemala and Honduras, including both citizens and industries,” a 2020 study on waste management in the region said. “Recycling and integrated waste management systems should be implemented everywhere within a country (including smaller towns and villages in the mainland).”

Fixing the landfill

The Guatemala City landfill is located in the Zone 3 neighborhood in the city’s north, and takes in everything from food waste to plastic to medical equipment — and not just from the city proper. Thirteen surrounding municipalities also rely on the landfill as their principal disposal site, which then feeds into the local watershed and ultimately pollutes the Caribbean hundreds of miles away.

Landfills may just look like simple holes in the ground where waste piles up. But they’re actually complex operations with sophisticated technology, intended to prevent waste from creating public health issues and environmental harm. Modern landfills usually include multiple “cells” for controlled dumping, a drainage and rainwater collection system, and a network of pipes and vents to prevent the buildup of methane gas, which is emitted as organic waste breaks down over time.

But the landfill in Guatemala City is decades behind technologically. Garbage piles up dozens of meters high, so unstable that it can shift like an ocean current, swallowing up garbage pickers unexpectedly. The lack of methane vents can lead to gas buildup, fires and toxic smoke.

And the lack of a formal water drainage system has led to a naturally flowing river of contaminated liquids moving out of the dump.

“I’ve rarely seen such a blatant and concrete example of unintended consequences,” said Trae Holland, executive director of Safe Passage, an NGO working in the area. “From a sanitation and waste management standpoint, the medieval approach in Guatemala City is transcending its physical location to become an international problem.”

Trash floating in the Caribbean. (Photo courtesy of Caroline Power)

Guatemala City municipal authorities didn’t respond to Mongabay’s request for comment about what it’s doing to actively address waste management at the landfill. Some organizations tell Mongabay they’ve worked closely with officials to improve the situation, saying they want this problem gone as much as anyone else does. Others say there’s little evidence that the government is taking any environmental action whatsoever.

In recent years, the government pushed back the landfill so it wasn’t encroaching on residential buildings. It decorated the entrance gate with flowers. But the prevailing waste management strategies appear to have gone unchanged.

“It’s this Arcadian paradise,” Holland says. “The front looks like the entrance to a university now that the garbage has been pushed away from the front. This is obviously not solving any problems, right? It’s just a PR move.”

But problems at the dump aren’t just technological. They’re also wrapped up in the political and social struggles of the country. It’s expensive and controversial, for example, to create a new landfill somewhere else. Zoning can be complicated, not only because the area must be strategically located to mitigate environmental hazards, but also because nearby residents and businesses would fight back against the plans.

Unregulated dumping has given rise to an entire informal economy for the impoverished residents of Zone 3, with families entering the landfill each day to pick out plastics and other items that can be sold to middlemen recyclers. Children used to pick trash out of the river, a practice that’s now banned. Gangs oversee a lot of what’s bought and sold there, complicating efforts by groups looking to help struggling families.

During the pandemic, the landfill shut down several times, putting so much stress on trash pickers that several households reported suicides by family members, Holland says. Gangs couldn’t collect extortion fees, which led to kidnappings of children and retaliatory violence.

As difficult as the last several years have been, Holland says, the pandemic may have gotten city officials’ attention for the better and may, in the long run, lead to improved waste management.

“The municipality, I can tell you right now, woke up to some of the issues in that community and in that zone that they were ignoring before,” he says. “And I feel very strongly, in fact, that that’s going to be a net positive.”

Temporary solutions

With systematic changes to the Guatemala City landfill slow to come, some stakeholders have shifted their focus downriver, where the trash is freer from the same complex social and political issues.

The Ocean Cleanup, an international organization engineering creative ways to remove plastic from the oceans, came to Guatemala in 2018 in hopes of developing a method for intercepting the trash on the Motagua River.

“If something is done about the source, that would be ideal, but I think we have to recognize that the brunt of this is more complicated than that,” CEO Boyan Slat tells Mongabay. He adds, “We asked ourselves, what is the fastest, most cost-effective way to stop this plastic from going into the ocean?”

Slat, a Dutch entrepreneur, founded The Ocean Cleanup when he was just 18, after having gone viral for a TEDx talk about what innovative technologies can bring to conservation efforts. His organization has raised millions of dollars since then, but has also been criticized for its flawed technology and lack of results.

In Guatemala, its pilot project involved installing “Interceptor 006,” a fence 50 meters (164 feet) wide and 8 m (26 ft) high that’s designed to catch plastic in its mesh while letting the water through.

The Interceptor 006 catching garbage during its trial this year. (Photo courtesy of The Ocean Cleanup)

In a video released by The Ocean Cleanup, the trash fence starts out looking like it’s going to succeed. The trash stops at the fence and starts to build up, with the water passing through free of plastic. But after a while, the sheer magnitude of trash gets to be too much and the infrastructure starts to bend. Then holes form and the plastic pushes through.

“We thought we truly cracked the nut,” Slat says, “that we collected what’s roughly a million kilos [2.2 million pounds] of plastic … and then seeing a big chunk of that disappear again, almost literally slipping through our fingers. In the matter of two hours, we went from the highest high to a substantial low.”

The Ocean Cleanup is working on a new type of interceptor that hasn’t operated anywhere else, and which will look “evolutionary rather than revolutionary” when compared to the previous one, Slat says. However, he doesn’t divulge any details about its design.

He also says the organization is working with local partners to develop recycling and incineration programs as well as methods of waste fraction (the sorting of waste into biodegradables, glass, batteries and other categories).

The Guatemala 2.0 solution, as Slat calls it, should be ready by the end of the first quarter of 2023. And while it won’t solve the waste management issues at the landfill or stop illegal dumping at different points along the Motagua River, it should help slow the amount of trash entering the Caribbean.

Banner image: Trash floats near a boat in the Caribbean. Photo courtesy of Caroline Power.

Citation: Kikaki, A., Karantzalos, K., Power, C. A., & Raitsos, D. E. (2020). Remotely sensing the source and transport of marine plastic debris in Bay Islands of Honduras (Caribbean Sea). Remote Sensing, 12(11), 1727. doi:10.3390/rs12111727

FEEDBACK: Use this form to send a message to the author of this post. If you want to post a public comment, you can do that at the bottom of the page.

Environmental watchdog charges REDcycle operators over secret soft plastics stockpiles

Environmental watchdog charges REDcycle operators over secret soft plastics stockpiles Environment Protection Authority Victoria charges RG Programs and Services, which faces a possible fine in excess of $165,000 Get our morning and afternoon news emails, free app or daily news podcast The operators behind REDcycle may face a possible fine of more than $165,000 after …