NEWPORT — Plastic pollution is a widespread problem throughout the world’s oceans and waterways, and environmentalists encourage people, businesses and governments to all take action.

The N.C. Coastal Federation, a Carteret County-based nonprofit dedicated to protecting the state’s coastal environment, hosted an online forum Thursday on microplastic pollution, and more than 300 attendees registered worldwide.

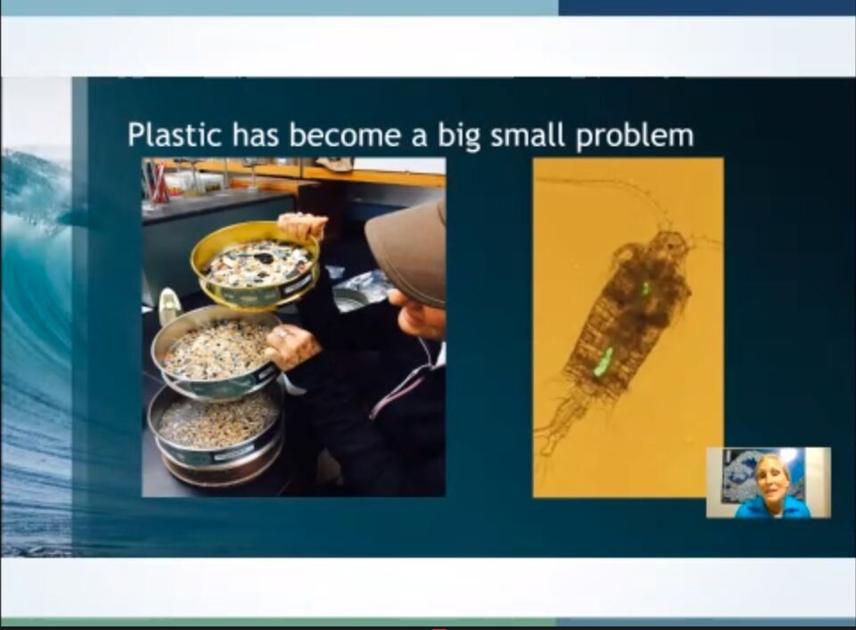

Microplastic is plastic that has broken down into pieces no bigger than 5 milimeters. Studies have found it polluting vast amounts of the oceans and inland water bodies, resulting in people and wildlife ingesting it, which can be hazardous to health.

NCCF Executive Director Todd Miller said a big part of the solution is raising public awareness of microplastic pollution.

“We’re still in the early stages of exposing this issue to the public,” he said. “We’re at the state where we know the issue is spreading.”

Mr. Miller also said microplastic pollution is tied to a lot of coastal issues the federation has been dealing with.

“Storm debris is a major issue,” he said. “As we’ve talked about coastal resiliency…in North Carolina, microplastics are just starting to come into the conversation. The important thing is going to be identifying where opportunities are to do something.”

NCCF assistant director of policy Ana Zivanovic-Nenadovic said microplastics have “permeated our lives” since the 1960s, when mass production of plastic products took off.

“It’s in the water, the air and the wildlife,” she said. “It’s a problem.”

Plastic Ocean Project Executive Director Bonnie Monteleone was one of several speakers who joined the forum. Ms. Monteleone said scientific study shows 11 million metric tons of microplastics go into the oceans annually from runoff alone, affecting 638 marine species.

“The plastics in the oceans aren’t creating an island,” she said, “it’s more creating a soup.”

Ms. Monteleno said plastics will break up into smaller and smaller pieces, but they never “break down,” that is they never lose the properties that make them plastics. Studies show microscopic plastics are being eaten by microorganisms, which are in turn eaten by larger and larger predators, causing these plastics to build up in their bodies.

“We used to intentionally dump plastic into the ocean,” Ms. Monteleno said. “An international law went into effect (in 1988). It took a good 20 years for a law to be made.”

One considerable source of microplastics are microfibers, tiny pieces of fiber that can be coated with plastic. N.C. State University graduate student Dr. Marielis Zambrano said microfibers can find their way into the water and the air through laundering synthetic fabrics, like polyester.

“You have microfibers coming off (synthetic fabrics) throughout the life cycle of a product,” NCSU Elis-Signe Olsson Professor of Pulp and Paper Science and Engineering Dr. Richard Venditti said.

Potential solutions include filters for washing machines and dryers, adding a finish to fabrics and replacing synthetic fabrics with natural, plant-based or biodegradable ones.

While all the effects of microplastics on human and animal health aren’t known, scientists have determined they are hazardous. California State Water Resources Control Board research scientist Dr. Scott Coffin said plastic additives can disrupt endocrines in humans.

He said a 2017 study showed 83% of worldwide tap water sources had microplastics in them.

“Currently there are no standardized methods to monitor (water sources) for microplastics,” he said.

As of Wednesday, a monitoring method is under development in California.

Water isn’t the only source of microplastics that get into people’s bodies.

“We find that air is likely our greatest exposure pathway,” Dr. Coffin said. “We find much of this (exposure) is indoors. We know microplastics don’t go away after you ingest them.”

Regulatory action is one part of the response to the issue of microplastics. Wake Forest University School of Law associate professor Sarah Morath said two things to consider when creating regulations to reduce microplastic pollution is what part of the lifecycle of plastics should be regulated and who should be responsible for doing the regulating.

“I think we’ve learned plastic is ubiquitous,” Ms. Morath said. “You can’t underestimate the importance of letting your elected representatives known you’re concerned about the issue.”

Mr. Miller agreed with Ms. Morath.

“I think people have to recognize this is an issue,” he said. “I think we’re on our way. I think we need to look at opportunities in North Carolinian to create role models through legislative action…We need to support the science.”

Contact Mike Shutak at 252-723-7353, email mike@thenewstimes.com; or follow on Twitter at @mikesccnt.