One third of all second-hand clothing shipped to Kenya in 2021 was “plastic waste in disguise”, creating a slew of environmental and health problems for local communities, a new report said Thursday.Every year, tonnes of donated clothing is sent to developing countries, but an estimated 30 percent of it ends up in landfills — or flooding local markets where it can crowd out local production.A new report shows that the problem is having grave consequences in Kenya, where some 900 million pieces of used clothing are sent every year, according to the Netherlands-based Changing Markets Foundation.Much of the clothing shipped to the country is made from petroleum-based materials such as polyester, or are in such bad shape they cannot be donated.They may end up burning in landfills near Nairobi, exposing informal waste pickers to toxic fumes. Tonnes of textiles are also swept into waterways, eventually breaking down into microfibres ingested by aquatic animals.”More than one in three pieces of used clothing shipped to Kenya is a form of plastic waste in disguise and a substantial element of toxic plastic pollution in the country,” the report said.The research was based on customs data as well as fieldwork by non-profit organisation Wildlight and the activist group Clean Up Kenya, which conducted dozens of interviews.Some of the clothing items were stained with vomit or badly damaged, the report found, while others had no use in Kenya’s warmer climate.”I have seen people open bales with skiing gear and winter clothes, which are of no use to most Kenyans,” Betterman Simidi Musasia, Clean Up Kenya founder, told AFP.- ‘Enormous waste problem’ -Between 20 and 50 percent of all donated clothing was not of a sufficient quality to be sold on the local secondhand market, the report found.Unwearable items might be turned into industrial wipes or cheap fuel for peanut roasters, swept into the Nairobi river, scattered around the market or sent to immense plastic graveyards outside the capital, such as the Dandora landfill.Story continuesSeveral waste pickers working at Dandora said they contracted breathing and asthma issues by inhaling smoke from burning plastic at the site, according to the report.Musasia said items should be better sorted at the point of donation before being shipped to Kenya, instead of being blindly passed on, to try and prevent the problem at the source.Experts say the problem of clothing waste has been exacerbated by the fast fashion boom in wealthier nations, where items — many made from synthetic fibres — might be worn only a few times before being discarded.The report called for the use of non-toxic and sustainable materials in textile manufacturing, and the establishment of more robust extended producer responsibility schemes around the world. “The Global North is using the trade of used clothing as a pressure-release valve to deal with fast fashion’s enormous waste problem,” it said.lam/jv/klm/imm

Author Archives: David Evans

Call for urgent overhaul of Australia’s monitoring of ‘astronomical’ plastic pollution problem

Call for urgent overhaul of Australia’s monitoring of ‘astronomical’ plastic pollution problem Australian Academy of Science points to over-reliance on volunteers and says more regular surveys needed Get our morning and afternoon news emails, free app or daily news podcast The Australian Academy of Science has called for an overhaul of the nation’s approach to …

Are everyday chemicals contributing to global obesity?

Obesity is on the rise almost everywhere, with more overweight and obese than underweight people, globally. According to accepted wisdom, blame lies squarely with overeating and insufficient exercise. A small group of researchers is challenging such ingrained assumptions, however, and shining a spotlight on the role of chemicals in our expanding waistlines.‘There are at least 50 chemicals, probably many more, that literally make us fatter,’ says Leonardo Trasande, an environmental health scientist at New York University in the US. An obesogen is a chemical that makes a living organism gain fat. Notable examples include bisphenol A, certain phthalates and most organophosphate flame retardants. They can push organisms to make new fat cells and/or encourage them to store more fat. Almost all of us often encounter such chemicals every day.

Over the past 20 years, calorie consumption is flat – but obesity has gone up

This may even help explain some discrepancies in data. Obesity rates have tripled since the 1970s, ticking up in the US from 30.5% in 2000 to 42.4% in 2018. ‘Over the past 20 years, calorie consumption is flat, or gone down slightly [in the US],’ according to Bruce Blumberg, a cell biologist at the University of California Irvine in the US. ‘But obesity has gone up.’ And it is not just humans. Body weights of animals such as dogs, cats, rodents and non-human primates – in research colonies and living feral – are also reported to be increasing. Blumberg and others are on a mission to persuade clinicians and others to take contributions to obesity from chemicals more seriously.

Weight gain

The hypothesis that chemicals encourage weight gain is perhaps not surprising, given that an expanded waistline is a side effect of some medicines. Antidepressants such as selective serotonin receptor inhibitors are associated with weight gain, and anti-diabetic drugs such as rosiglitazone were long known to add a few pounds.

Blumberg coined the term obesogen in 2006, when his lab showed that tributyltin chloride promoted fat formation in mice. ‘Mice we expose to tributyltin don’t eat more, and they don’t exercise less than animals not exposed to it,’ says Blumberg. ‘But they use calories differently – they store more as fat. That’s very relevant to humans.’ Exposure in utero leads to ‘strikingly elevated lipid accumulation’ in fat deposits, liver and testis of in neonate mice. Another early study showed that an estrogen drug (diethylstilbestrol) in pregnant mice significantly increased body weight of their offspring – as adults.

Starvation was a constant threat to our ancestors. ‘Weight gain is important to the survival of the species,’ says Robert Lustig, emeritus professor of endocrinology at the University of California, San Francisco, and campaigner against childhood obesity. ‘There are multiple paths to it.’ Some obesogenic chemicals flick biochemical switches to store fat for a rainy day.

Lusting and others described obesogen exposure as an underappreciated and understudied factor in the obesity pandemic, in a recent review of causal links.1 Dozens of animal studies are cited. Studies revealed, for example, that mice fed DEHP (bis(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate) consume more food, pile on weight and store more belly fat. We couldn’t ethically give people DEHP, but people are nonetheless exposed to it every day: it improves the flexibility of polyvinyl chloride (PVC) and is used in floor and wall coverings, food containers, toys and cosmetics.

While you can’t dose people, you can analyse blood for chemical contaminants. Those with high phthalate levels are more likely to gain weight over the next 10 years, research has shown. Perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) – so-called forever chemicals – are also obesogens. They are villains in a clinical trial in the US (POUNDS Lost) investigating weight loss in 600 overweight and obese adults on one of four diets. Plasma concentrations of PFASs did not influence weight loss during six months of dieting, but women with high levels at the start of the trial experienced significantly more weight regain.

Mechanisms

Fat tissue expands due to increased cell number and size during foetal development, childhood and adolescence, while fat cell (adipocytes) numbers remain stable during adulthood, so long as weight remains stable. The primary regulator of fat cell formation (adipogenesis) is considered to be peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma (PPAR-).

If you express this receptor on a mesenchymal stem cell, it becomes a pre-adipocyte, which are important cells that can become bone cells, immune cells or fat cells. If PPAR- then becomes activated by long-chained fatty acids, it becomes a fat cell. When triggered inside an existing fat cell, the cell accumulates more fat. ‘If you activate the receptor well, with full agonists, then the cells generally become healthy white fat cells,’ explains Blumberg.

This receptor has a large promiscuous pocket that is vulnerable to hacking by multiple obesogenic ligands. One of Blumberg’s early discoveries was that tributylin activated PPAR-He later found that it hits two parts of PPAR- at the same time, making white fat cells good at storing fat, but not good at releasing it. ‘The worst thing you could have – an unhealthy fat cell that stores but doesn’t give up its fat,’ Blumberg explains.

A long list of environmental contaminants bind to this fat receptor – plasticisers, phthalates and BPA and its analogues; flame retardants; and per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). All are obesogens. But this is not the only route. Obesogens can alter appetite control, impact the microbiome or change how much energy your body burns at rest (basal metabolic rate) via the thyroid hormone receptor, say researchers. Resting metabolic rate represents 70% of an average person’s energy expenditure, so lowering it has a major impact on weight. ‘People with the highest levels of perfluorinated chemicals have lower resting metabolic rates, a study has shown, and regain weight more quickly,’ notes Blumberg.

Phthalates can change how the body processes a meal and turn it into fat

Also susceptible to obesogenic chemicals are oestrogen and androgen receptors, glucocorticoid receptors and the retinoid X receptor, which promotes fat cell formation and the proliferation of precursor fat cells. Bisphenol A and its analogues, says Blumberg, ‘can target probably a dozen different pathways in the body’, for example. In vitro, BPA influenced PPAR-and lipid accumulation, while exposing unborn male mice to low dose – but not high dose – BPA stoked up body weight, food intake and number of fat cells, as well as insulin regulation, the enzyme needed to control blood sugar.

Binding fat cell receptors, fully or partially, can even shift a person’s metabolism. ‘Imagine you’ve had a good workout, you’ve eaten a good protein meal, and you are thinking you are going to gain some muscle,’ says Trasande. But chemicals such as phthalates can ‘change how the body processes a meal and ultimately turn it into fat or carbohydrate instead’, he warns. This turns on its head the simplistic story of overeating fat leading to a flabby girth.

Calorie counting

The obesogenic community is adamant that calorie counting has led clinicians and the public astray. And they are starting to spread their beliefs to the medical community. If you relegate weight gain to simple maths, energy in and energy out, then you gain weight if you eat too much and exercise too little. This is the energy balance model, and its major premise is that a calorie is a calorie, and you must not end up with too many. ‘It’s about two behaviours, gluttony and sloth, and therefore if you are fat, it is your fault,’ Lustig sums up. But he says there’s little evidential support.

Another proponent of the obesogen hypothesis is Jerrold Heindel, formerly involved in grant funding decisions for environmental chemicals and disease at the National Institutes of Health in the US. He became interested in the early 2000 . Now retired, he was pivotal in the recent publication of three review papers summarising evidence on obesogens.

Like others, he is frustrated about current approaches to obesity. While exercise improves health, it does not cure obesity, and dieting results in weight loss that is rarely sustained. Yet clinicians remain focused on diets, drugs and surgery. ‘If all that worked, we should see a decline in obesity, but we are not seeing a decline at all. It’s going up, especially in children,’ says Heindel. What many nutritionists miss is a cause of increased eating, which is obesogenic chemicals that alter sensitivity to weight gain, he adds.

His colleague Lustig views energy storage as coming first and increased food intake following. ‘In this energy storage model,’ he says, ‘biochemistry comes first, then the behaviours.’ He arrived at this conclusion partly from a study of children cured of a brain tumour, but obese because a drug ramped up their insulin levels. This pushed energy into fat, leaving them lethargic and hungry.

Ubiquitous foes

Obesogens are ubiquitous in our environment. They are present in dust, water, processed foods, food packaging, cosmetics and personal care products, but also furniture and electronics, air pollutant, pesticides, plastics and plasticisers. Phthalates and organophosphates can be detected in around 90% of Americans, notes Chris Kassotis, a toxicologist at Wayne State University in Detroit, US. ‘They’re high-production chemicals, pretty ubiquitous, with high human exposure,’ he notes.

Kassotis has taken an interest in the finer things in life – specifically, house dust, a complex mixture of hundreds, sometimes thousands, of chemicals. In 2017, Kassotis reported that house dust impacted mouse fat cells. Ten of 11 extracts spurred triglyceride accumulation in preadipocyte mouse cells.

‘Really low levels of dust were able to drive the development of fat cells in our cell model,’ recalls Kassotis. Around 20μg of dust impacted the fat cells, a small amount considering the Environmental Protection Agency in the US estimates that a child consumes about 50mg of dust per day. A subsequent study found that about three-quarters of dust samples antagonised a thyroid receptor, and about one-fifth activated PPAR-Ultimately, the Karssotis lab tested over 350 samples and around 90% showed activity in mouse fat cells.

Environmental contaminants are not the only source. Many ingredients added to processed foods are sources too, say obesogen researchers. ‘When we add sugar to make a food taste better, we’re making it more obesogenic,’ says Blumberg. Table sugar, sucrose, consists of one glucose and one fructose unit, with fructose found naturally in fruit, honey, and root vegetables. Fructose is the most concerning, as far as Lustig is concerned. ‘It inhibits mitochondrial function, which is necessary to burn energy,’ he explains. ‘If you don’t burn it, then it gets turned into fat and stored.’

Fructose was traditionally consumed around harvest time, a natural signal for the body to store fat in the liver in preparation for the coming winter, says Lustig: ‘This makes evolutionary sense, but the problem is that it is now available all the time.’

Some foods advertised as low calorie or for weight loss may contain obesogens. ‘Diet sweeteners cause weight gain,’ asserts Lustig, ‘because they raise your insulin levels.’ Research in animals and humans show a positive link between insulin levels and obesity. The addition of artificial sweeteners such as aspartame, saccharin and sucralose to foods has successfully reduced sugar intake, but not obesity levels.

In one study, children born to mothers in Canada who regularly consumed non-nutritive sweetened drinks had a higher body mass index and more fat tissue by age three. The researchers then fed sucrose, aspartame or sucralose to pregnant mice. Male mice born to mothers on aspartame and sucralose showed body fat rises of 47% and 15%, respectively.

Also suspected to be obesogens are the flavour enhancer monosodium glutamate, food emulsifiers such as dioctyl sodium sulfosuccinate, and parabens used as preservatives in foods and in personal care products. Some food additives such as carboxymethylcellulose are believed to increase body weight – at least in mice – by altering the microbiota in the gut. The additive thickens foods and stabilises emulsions such as in ice cream products. Reducing exposures to such common substances will be challenging.

Although there is widespread evidence from animal models, some experts in other fields like toxicology are not fully convinced. They make the point that environmental obesogens like these are generally low potency, which when combined with low exposures to most people, means there is very low risk. And with controlled experiments difficult to carry out in humans, they may remain unconvinced. Obesogen researchers counter that many scientists don’t yet fully consider endocrine disruptors to be important factors.

Regarded safe

Regulation is also a struggle. ‘We operated under the assumption that only the dose makes the poison,’ says Trasande. This has allowed endocrine-disrupting chemicals – of which obesogens are a subset – to dodge regulations because their effects can be subtle and occur at low doses. Parts per billion of tributyltin influence snails and fish. The same is true of fat cells. ‘Tributyltin causes effects at doses which people are exposed to, such as 20ppb,’ says Blumberg. ‘You can make animals obese at those levels.’ This sets a high bar from those in the field who wish for policy action against these chemicals. ‘[Researchers] are findings effects below the doses that governments say is safe for many of these chemicals,’ warns Heindel.

There are hundreds of endocrine-active chemicals in plastics

Also, many food additives that are obesogens or suspected obesogens are designated ‘generally regarded as safe’ by the Food and Drug Administration in the US. This applies to a substance used in food prior to 1958 or with a substantial history of consumption. ‘They were never tested,’ says Blumberg, ‘but regulators should go back and test them.’ The recent proposal by the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) to lower the reference dose of BPA 100,000-fold is a case in point, according to Blumberg – ‘it brings it into line with what the endocrine disrupting community has been saying for years’. Such ‘innocent until proven guilty chemicals’ are a problem, warns Trasande.

Consumers, nevertheless, can reduce their exposures. Among suggestions are to reduce use of plastic containers and packaging, and never microwave with plastic. ‘Do not eat packaged processed food. It’s full of obesogens. Buy fresh ingredients and make a meal,’ advises Blumberg. A Norwegian study found that one-third of the chemicals in 34 plastic consumer products disrupted the development of fat precursor cells in vitro. Analyses revealed a motley assortment of additives, breakdown products and manufacturing residues. ‘There are hundreds of endocrine-active chemicals in plastics,’ says Blumberg. Glass is a healthier alternative, he adds. According to Trasande, studies show that reducing canned food consumption reduces blood bisphenol levels. Cast iron and stainless steel are alternatives to nonstick cookware, which is made using PFOA.

Assessing how much chemicals may be contributing to the obesity epidemic is difficult. ‘There’s a tip of the iceberg phenomenon. There’s what we know, and what we don’t know, but the evidence is evolving,’ says Trasande. It is not that obesogens are the cause of the obesity pandemic, but a contributing factor. There is little monitoring of chemical levels within people, and government action is needed here. ‘We need to know who is exposed and what the critical times of life are,’ says Blumberg. Once programmed to have a certain number of fat cells, you will never have less.

Unfortunately, there are worrying signs of possible impacts running down generations. Mice whose grandparents were exposed to tributyltin in utero are affect. One study showed mother mice exposure to low doses of tributyltin during pregnancy predisposes (unexposed) male mice in the fourth generation to obesity via a so-called ‘thrifty phenotype,’ meaning a propensity to store fat and hold onto it during fasting. ‘We don’t have human data for transgenerational effects yet, but you can see how scary that would be,’ says Heindel. ‘Increased obesity in children is still due to poor diet and exposure during pregnancy and childhood, but maybe some of that exposure was through their grandmother.’

While obesogens are not the sole cause of the obesity problem, these chemicals deserve more attention and potentially stricter regulation. And those advocating action say that the obesogen hypothesis offers a preventive approach, so that reducing exposures should reduce the incidence or severity of obesity.

Anthony King is a science writer based in Dublin, Ireland

From lab to market: Bio-based products are gaining momentum

In the 1930s, the DuPont company created the world’s first nylon, a synthetic polymer made from petroleum. The product first appeared in bristles for toothbrushes, but eventually it would be used for a broad range of products, from stockings to blouses, carpets, food packaging, and even dental floss.

Nylon is still widely used, but, like other plastics, it has environmental downsides: it is made from a nonrenewable resource; its production generates nitrous oxide, a potent greenhouse gas; it doesn’t biodegrade; and it sheds microfibers that end up in food, water, plants, animals, and even the clouds.

Now, however, a San Diego-based company called Genomatica is offering an alternative: a so-called plant-based nylon made through biosynthesis, in which a genetically engineered microorganism ferments plant sugars to create a chemical intermediate that can be turned into nylon-6 polymer chips, and then textiles. The company has partnered with Lululemon, Unilever, and others to manufacture this and other bio-based products that safely decompose.

“We are at the start of a sustainable materials transition that will reinvent the products we use every day and where they come from,” says Christophe Schilling, Genomatica’s CEO.

In September, President Biden launched a $2 billion biotechnology and biomanufacturing initiative.

Using living organisms to create safe materials that break down completely in the environment — where they can act as nutrients or feedstock for new growth — is just one example of a burgeoning global movement working toward a so-called bioeconomy. Its goal isn’t limited to replacing plastics but takes aim at all conventional synthetic products — including chemicals, concrete, and steel — that are toxic to make or use, difficult to recycle, and have outsize carbon footprints. In their place will come products made from plants, trees, or fungi — materials that, at their end of life, can be safely returned to the Earth or recycled again and again. The bioeconomy is still small, in the global scheme of things, but the push to turn successful research into manufactured products is growing, propelled by several factors.

Subscribe to the E360 Newsletter for weekly updates delivered to your inbox. Sign Up.

Seafloor plastic pollution is not going anywhere

The world produces about 380 million metric tons of plastic annually. A huge share of plastic debris ends up in the world’s oceans, rivers, and lakes in the form of microplastics, contaminating countless ecosystems and threatening animals and humans.

A new study conducted in the Mediterranean Sea hints at the scale of the problem. Researchers found that the mass of particles that have settled to the seafloor mimics global plastic production over the past 5 decades. Once buried in sediment, the study found, microplastics remain intact.

Scientists have long scoured sediment cores—cylinders of mud drilled belowground and brought to the surface—for evidence of microplastic pollution in oceans, lakes, and other aquatic environments. The cores, they found, provide a timeline of the “plastic age,” the period starting in the 1950s when humans started producing the material on an industrial scale.

This newsletter rocks.

Get the most fascinating science news stories of the week in your inbox every Friday.

Plastic Fills Half a Century of Mediterranean Sediments

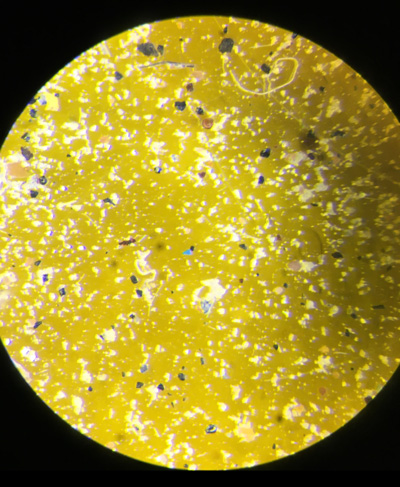

In the new study, researchers collected more than 10 cores from the seafloor of the Balearic Sea, a part of the Mediterranean near the Ebro delta, where one of Spain’s longest rivers enters the sea. The spot where the cores were collected, 100 meters (330 feet) below the surface, concentrates pollution discharged by the river, including plastic debris from bags, vessel paint, clothes, cosmetics, and other sources.

The researchers sliced the cores into 1-centimeter-thick (0.4-inch-thick) disks and used isotopic dating of lead naturally present in the sediments to estimate the age of five cores. Each slice encapsulated about 10 years of history.

Tanya Plibersek urged to intervene to stop stockpiled soft plastics from being dumped

Tanya Plibersek urged to intervene to stop stockpiled soft plastics from being dumped Environmentalist alliance says plastic waste from failed supermarket-backed recycling scheme can be safely warehoused until it can be recycled Follow our Australia news live blog for the latest updates Get our morning and afternoon news emails, free app or daily news podcast …

We break down your plastic-bag alternatives

Canada’s prohibition on the sale of single-use plastic bags doesn’t come into effect until the end of this year, but it’s already getting harder to find them when you’re shopping.Numerous grocery chains in Ontario have been removing traditional plastic bags as an option for shoppers who don’t bring their own.It’s part of the federal government’s ambitious zero plastic waste strategy. Canada is aiming to remove millions of tonnes of difficult-to-recycle plastic waste, as well as plastic pollution, and mandate a minimum of 50 per cent recycled content in plastic packaging.It’s a major change to the retail landscape in this country. But there are questions about the options being used to replace the ubiquitous plastic bag — and about the impact the ban will have.Many of the bags that grocery stores are selling appear to be fabric — they too are also made of plastic, are themselves unrecyclable and many are manufactured in China. The cheaper ones have no recycled content.“They use different types of plastic resins that are much stronger and have more tensile strength, and that allows the bag to be reused multiple times,” says Cal Lakhan, a York University research scientist. “But the drawback is that it requires a significant amount of resources to make that bag.“So, unless you’re using it hundreds of times, you might not actually get a positive environmental return.”The bags will also be more expensive, anywhere from $0.15 cents and up for a paper bag — which can also be difficult to recycle because of food contamination and paper quality — to $5 for a reusable plastic fabric bag or more for other materials.Single-use plastic bags are just one of the items being banned in Canada. The others include single-use food service ware, stir sticks, straws and ring carriers.The government says the regulations are meant to “prevent plastic pollution by eliminating or restricting the six categories of SUPs (single-use plastic) that pose a threat to the environment,” and to “make it easier for Canadians to enjoy the benefits of clean natural areas, and help foster the transition to a circular economy.”There are those like Lakhan who describe it as a “feel-good policy” that won’t do much to reduce our overall plastic waste.“Almost all the emphasis is placed on consumers and the residential sector,” says Lakhan. “But we’re a drop in the bucket of the larger problem. “In terms of all the waste generated, 90 per cent of it comes from the industrial sector, not from the residential sector,” says Lakhan, referring to plastic waste that enters the environment through manufacturing and industrial processes.Bans on single-use plastics, such as the one in Canada, are becoming more common around the world as jurisdictions look for ways to reduce the highly visible consumer waste that is littering shore lines. That plastic makes its way into waterways where it endangers marine life and ecosystems. It can also become brittle and breakdown into harmful microplastics, which not only contain harmful chemicals but attract others already in the environment.In the E.U., more than two-thirds of ocean litter is comprised of the 10 most common single-use plastic items found on European beaches. The union is banning the sale of those items, including cutlery, plates, straws, stir sticks, cotton bud sticks and balloons, but not bags. On other items, it will require labelling to inform consumers about the harm done to nature if the item becomes litter. The EU is also introducing waste management and cleanup obligations for producers.“Plastic bags and other single use plastics are the top items we find in the environment,” says Britta Baechler, associate director of ocean plastics research for Ocean Conservancy, a non-profit based in Washington, D.C.“They’ve been detected in the stomachs of all kinds of marine animals around the world. So they’re extremely problematic. And again, they will break up into what we call microfilm, small flexible pieces of plastic which can be ingested by any number of living organisms.”Since the 1950s, about 40 per cent of plastic produced every year is designed to be thrown away after one use, according to an article published in nature.com last year.In Canada, about 90 per cent of plastic ends up in landfills.Items like single-use plastic bags, which are made of a low-density polyethylene, are cheap to make but difficult and cost-prohibitive to recycle. And the bags, as well as other plastic film can easily be contaminated by any food it’s in contact with.“When we talk about sustainability, it’s important to remember that there is an environmental, economic and social dimension,” says Lakhan. “And we tend to just fixate on the environment.“The economic aspect of trying to recycle plastic film is once again thousands of dollars a ton,” he says. “And you have to ask yourself, is that money well spent given that the end product is still low grade and will still ultimately end up in landfills.”California has tried to create a viable system to recycle plastic grocery bags.The state banned single-use plastic bags in 2016, but allowed grocery stores to sell thicker plastic film bags, manufactured by companies in California, made of polyethylene, including 40 per cent recycled content.Grocery stores were made responsible for creating a closed-loop system, installing bins in the front of stores to collect the bags and ensuring they are recycled. The cost is born by consumers who are charged $0.10 a bag.The bags, along with more pristine shrink wrap from pallets of packaged food deliveries, were supposed to be collected and sent to distribution centres and processed into a plastic flake used for agricultural ground cover and drip tape for irrigation.But the front-of-the-store collection bins were removed during COVID and haven’t been replaced.Mark Murray, executive director of Californians Against Waste, says the companies reclaiming the bags have figured out that it’s cheaper not to have to separate the pallet wrap from the bins of potentially contaminated, used grocery bags.“It’s an economic barrier. It’s a pain-in-the-ass barrier,” says Murray. “It is, you know, folks whose job is not really recycling, but minimizing cost, who are not supporting the objectives that the retailers agreed to as part of this legislation.”The state’s attorney general is now investigating whether the reusable plastic bags are actually being recycled. Although the legislation says the bags must stand up to 125 reuses, it’s thought most are reused once — to line a garbage bin. Murray’s organization hopes the investigation will result in the bins being returned as well as proof that the bags are being recycled.So far, the Canadian ban on single-use plastic bags doesn’t have the same teeth.The regulation stipulates that reusable bags can be made of plastic fabric “as long as they will not break or tear if used to carry 10 kg over a distance of 53 m 100 times.”“The Single-use Plastics Prohibition Regulations do not contain specific testing methods, nor do they require regulated parties to provide proof of testing for single-use plastic items placed on the Canadian market,” said Environment Canada in an email. “Retailers are encouraged to discuss the requirements of the Regulations with their suppliers.”RELATED STORIESThe Canadian regulations also say the bags must stand up to a “single domestic wash.” Reusable bags should be wiped down or washed often, a recommendation because meat and dairy can contaminate the bags.But that recommendation also has the potential to add more microplastics to the environment, as washing is one of the major ways that fibres from plastic materials are released into wastewater.“There’s a possibility that laundering reusable bags at high temperatures and agitating them and everything can release microplastics because they’re created from synthetics,” says Baechler, of Ocean Conservancy.Guidelines that stipulate fewer washes between use, washing on cold temperatures, on a gentle setting, with mild detergent, could help reduce the release of microplastics, says Baechler.The good news is that some grocery chains are also pursuing solutions to reduce plastic waste.Walmart Canada eliminated single-use plastic shopping bags in April of last year and says that move has prevented more than 527 million single-use plastic shopping bags from entering circulation.The chain is trying to create a circular economy for its reusable bags, running a pilot at its Guelph store where it has installed a “GOATOTE” kiosk. Customers can check out clean reusable bags for a fee, and return them within a month, after which they are cleaned, sanitized and put back into circulation in the kiosk.Walmart says it is also reviewing opportunities to take back bags used for home delivery.And Sobeys, which held a contest last year in Atlantic Canada to find a sustainable alternative to plastic wrap on its in-store meat and seafood packaging, is working with the winner of that contest to develop a potential fibre replacement.More of those “upstream” innovations are needed to reduce our reliance on plastic, says Baechler. “We drastically need to reduce the amount of single use plastics and packaging that we produce. We need to create better. We need to find alternatives. We need more sustainable materials, and we need different delivery methods like refillable or reusable bags,” as well as recycle.“And the problem with plastic bags is they are not recyclable,” says Baechler. “They gum up the recycling equipment. So they’re hugely problematic. They’re not circular and banning these items makes people change behaviour. And that’s ultimately a piece of the solution puzzle.”SHARE:JOIN THE CONVERSATION Anyone can read Conversations, but to contribute, you should be a registered Torstar account holder. If you do not yet have a Torstar account, you can create one now (it is free)Sign InRegisterConversations are opinions of our readers and are subject to the

Jeremy Pare: Can the EPA strategically buy its way to waste reduction and increased recycling?

Can the EPA strategically buy its way to waste reduction and increased recycling? | The Hill Skip to content Getty Images The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) published a report last year finding that plastic pollution is quickly increasing as waste management and recycling efforts are falling short. The organization found that the …

Marcus Strom: Think plastic pollution is your own fault? That’s rubbish

February 13, 2023 — 7.00pm February 13, 2023 — 7.00pmNormal text sizeLarger text sizeVery large text sizeThe fallout from the collapse of the soft-plastics recycling programs in Australian supermarkets continues with news that millions of plastic bags kept aside for recycling are destined for landfill.And despite plastics recycling programs being common for many years, production of single-use plastics continues to surge.A stockpile of plastic bags in a Sydney warehouse. Nearly 12,400 tonnes of soft plastics have now been found in 32 locations across three states.These revelations expose more than just a failure of intent from the recyclers and the supermarkets. They show that they are more useful for greenwashing than dealing with the growing global mountain of plastics.Australians want to do the right thing to deal with plastics pollution. But the recycling schemes that have been on offer have barely touched the surface. The result? While people feel they are “doing their bit” for the environment, behind the scenes, recycling schemes make handy profits while the real global polluters are let off the hook.Central to the thinking of these schemes is that you, personally, are responsible for pollution and global warming. Yes, it’s all your fault. The same with being worried about your individual “carbon footprint” or being guilt-tripped for taking holidays.This has the outcome of demobilisation: sidetracking people from action to demand real change, while making individuals feel guilty and responsible for a planet-wide trashing of our environment.In fact, it’s not “your fault” but is a design feature of an economic system that accumulates more and more wealth for its own sake; that churns through more and more resources to feed that gluttony.Options for individuals to take their plastics and paper for recycling have been around for many years. Yet these “acts of consumer power” haven’t stopped masses of plastics forming in our oceans; a crisis so bad that the World Economic Forum in 2016 warned that plastics could outweigh fish in our oceans by 2050.Stockpiles of soft plastics found in Sydney warehouses.Credit:EPA NSWAdvertisementWhen single-use plastics were removed, supermarkets adopted “environmentally conscious” multi-use bags at 15¢ a pop.Many of these bags – worse for the environment than the bags they replaced – are used once and end up in landfill. Further, they become a revenue source for the supermarket chains. Queensland University of Technology academic Professor Gary Mortimer predicted the change to “reusable” plastic bags could deliver an extra $71 million a year in profits to retail giants Coles and Woolworths.Again, it is part of an ideology that tells people they are individually responsible for environmental degradation when in fact it is a global profits system and a few hundred companies worldwide that are trashing the planet.While the exact data are contested, a 2017 study argued that just 100 fossil fuel and cement companies contributed to 71 per cent of greenhouse pollution since 1988. Rather than tackle these polluting giants, individuals are asked to “do their bit”.Individual recycling schemes, like carbon offset schemes, have more in common with religious penance than urgent action to deal with plastics pollution or greenhouse gas emissions.As pointed out some years ago by Carbon Trade Watch and UK research outfit The Corner House, the push to make individual consumers feel guilty and responsible and pay a “little bit more” has more in common with medieval indulgences than real action on the environment.During Europe’s Dark Ages, the church told the benighted and sinning masses that the priesthood and assorted clergy had an abundance of holiness, while the individual believer was a sinner and damned to hell. But by purchasing indulgences from the church, they could transfer some of that holiness to their rotten lives, offsetting their sinful practices.Sound familiar?REDcycle does face prosecution in Victoria for failing to disclose its mountains of plastics. But the maximum fine is $165,000. Chicken feed.In NSW, the Environment Protection Authority has told Woolworths and Coles to clear the REDcycle warehouses at a potential cost of $3.5 million. Together, both companies made about $2.5 billion in profit last year.These companies will get away with a slap on the wrist. Meanwhile, oil companies continue to pump plastics into the environment, governments greenwash and climate protestors are threatened with prison.This tells us something about how seriously we are taking the climate crisis: punish the annoying Cassandras, let the real sinners off the hook.The Opinion newsletter is a weekly wrap of views that will challenge, champion and inform your own. Sign up here.Marcus Strom is a journalist. He worked as a press secretary in the Albanese government.Connect via Twitter.Most Viewed in Environment

Derailed train in Ohio carried chemical used to make PVC, ‘the worst’ of the plastics

The flames and deadly black smoke that billowed high over a small town on the Ohio and Pennsylvania border Monday were an acute reminder of a type of commonly used plastic with a particularly troublesome environmental and health record.

To prevent exploding rail cars, flying shrapnel and the uncontrolled release of killer gases, authorities vented vinyl chloride, a precursor of polyvinyl chloride, or PVC, and then burned the vinyl chloride in what officials described as a controlled manner, following Friday’s 50-car Norfolk Southern Railroad train derailment near East Palestine, Ohio, about 55 miles northwest of Pittsburgh. Local media showed dramatic video of an explosion and fire after Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine and Pennsylvania Gov. Josh Shapiro ordered evacuations.

On Tuesday, Ohio Director of Public Safety Andy Wilson said at a press conference that the fire was out and there had been no serious injuries, CBS Pittsburgh reported.

While the drama played out in Northern Appalachia, the story actually begins with an insatiable global demand for plastic and what United Nations officials describe as a “triple planetary crisis of climate change, nature loss and pollution.”

Vinyl chloride has been used to make polyvinyl chloride, used commercially to make such products as floor tiles, roofing and tents, for nearly 100 years. And there have been battles between industry and environmentalists over PVC for decades.

The versatile form of plastic that can be made to be rigid and durable for pipes, or soft and flexible for products such as intravenous bags and tubing, is no longer used as much as in the past in food packaging due to environmental health concerns. But it’s still a major building material for the construction industry, including siding and windows.

But one national environmental group, the Center for Biological Diversity, has been pressing the Environmental Protection Agency since 2014 to regulate PVC waste as hazardous. And health experts have also talked about having PVC declared a “persistent organic pollutant” under the 2001 United Nations Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants, a treaty that seeks to protect human health from chemicals that remain intact in the environment for long periods.

Those chemicals now litter the planet, accumulate in the fatty tissue of humans and wildlife, and have harmful impacts on human health and the environment. The U.S. has not ratified the treaty but participates as an observer.

“This derailment and explosion, while it’s not discharging PVC, it is indicative of the hazardous nature of this material,” said Emily Jeffers, an attorney at the Center for Biological Diversity. “As long as we continue to use PVC, we will continue to have accidents like this and it is entirely preventable.

“If we regulate PVC as the hazardous waste that it is, that could potentially force producers to develop materials with less toxic properties,” Jeffers added. “We lived without PVC before and I am pretty sure we can live without it again.”

Petrochemical facilities that make or use vinyl chloride or PVC are often found in communities of color in states like Louisiana, Texas and Kentucky that shoulder the health burdens from their polluting emissions.

EPA last May agreed to look into a 2014 petition from the Center for Biological Diversity to designate PVC a hazardous material, following a 2021 lawsuit seeking the same designation.

In January, the agency made a tentative decision denying the request, arguing that regulations would not have a meaningful impact while adding that the agency didn’t have the time or resources to create new PVC regulations. A public comment period closes Monday.

Like other chemicals, PVC has its own lobbying group in Washington. Called the Vinyl Institute, it touts the benefits of vinyl and the vinyl industry, which it said encompasses nearly 3,000 vinyl manufacturing facilities, more than 350,000 employees and an economic value of $54 billion.

PVC and vinyl are the third most used plastics in the world, according to the institute, which says on its website: “We are fiercely committed to achieving the policy agenda that helps the U.S. vinyl industry grow and create jobs.”

PVC has been used a lot, said Dr. Philip Landrigan, a pediatrician, epidemiologist and director of Boston College’s Global Public Health Program and Global Observatory on Planetary Health. But, he added, “it has problems at every stage” of its lifecycle, beginning with potential dangers to workers who make it.

Vinyl chloride is classified as a known human carcinogen. Researchers in the 1970s first linked its occupational exposure to a rare form of cancer—angiosarcoma of the liver—to rubber workers at a factory in the Rubbertown complex of chemical plants in Louisville, Kentucky. “There’s also some evidence it causes brain cancers,” he said.

PVC also contains a variety of chemical additives, such as phthalate plasticizers, some of which are blamed for disrupting the human endocrine system.

“There is good evidence” that toxic ingredients in PVC “can leach out of plastics products and get into drinking water or blood products,” said Landrigan, whose research has helped drive U.S. public health policies on childhood lead exposure, pesticide exposure and the response to health impacts of 9/11 rescue workers in New York.

The industry has disputed such assertions. A 2017 report, for example, from the PVC Pipe Association maintains that PVC piping meets the “highest standards for quality and safety.”

Vinyl Institute spokeswoman Susan Wade said that PVC can and is being recycled, and according to the institute’s website, the industry has a goal of boosting the recycling of vinyl materials. “We know we have a good story to tell,” she said, pointing to a lifecycle carbon emissions study from McKinsey & Company that shows using PVC sewer pipes has less impact on the climate than using pipes made from concrete or iron.

Keep Environmental Journalism AliveICN provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going.Donate Now