Plastics appear everywhere: from human placentas to chasms 36,000 feet beneath the ocean’s surface. Will we ever be rid of them? Elizabeth Kolbert writes for The New Yorker.In a nutshell:Born in 1865 out of a quest to eliminate elephant ivory from the billiard ball supply chain, plastics are now being spewed forth at an annual production volume of over 800 billion pounds. As plastics break down into microplastics and disperse, they make their way to the most distant parts of our planet and infiltrate the internal organs of species up and down the food chain with toxic chemicals. No amount of recycling, reusing or repurposing is going to solve the plastics problem.Key quote:Kolbert presents a reality check from Matt Simon, the author of a book about microplastics: “So long as we’re churning out single-use plastic . . . we’re trying to drain the tub without turning off the tap. We’ve got to cut it out.”Big picture:Reducing plastic pollution cannot be seriously entertained without a commitment to reducing, if not eliminating, plastic production. That in turn would involve a winding down of the petrochemical industry at precisely the point in time when Big Oil, faced with an energy transition to renewables, is looking to plastics as one of the mainstays of future profits. The oil and gas industry, protected by massive political might and bankrolled by decades of record profits and willing financiers will not go quietly.Read Elizabeth Kolbert’s astute analysis inThe New Yorker.

Category Archives: Ocean

Why you should stop using laundry pods right now

Doing right by the planet can make you happier, healthier, and—yes—wealthier. Outside’s head of sustainability, Kristin Hostetter, explores small lifestyle tweaks that can make a big impact. Write to her at climateneutral-ish@outsideinc.com.

Oh, the irony. In trying to wash my clothes the green way, I was greenwashed. You might even say I was taken to the cleaners. Or hung out to dry.

Let me explain: more than a year ago, I learned that laundry pods—encased in dissolvable plastic—were bad for the environment. In my quest to find more sustainable, plastic-free household products, I was thrilled to come across laundry “eco-strips,” as an easy swap-out. Instead of the typical plastic jug, the thin compressed sheets are packaged in a recyclable cardboard envelope and marketed as plastic-free. I promptly ordered a year’s supply and told everyone who would listen about my new discovery.

My latest preferred laundry kit, clockwise from top: lavender essential oil, soap nuts in a muslin sack, and wool dryer balls. (Photo: Kristin Hostetter)

Imagine my surprise when I discovered that what holds those innocuous little strips together is a sneaky type of plastic called polyvinyl alcohol, or PVA. It’s the same exact stuff that encases laundry (and dishwasher) pods, and though it’s designed to dissolve as soon as it hits water, it is indeed plastic. A very controversial type of plastic. To learn more about PVA and come up with sustainable alternatives, I connected with Dianna Cohen, co-founder and CEO of Plastic Pollution Coalition, a nonprofit working towards a world free of plastic pollution and its toxic impacts.

The PVA Controversy

PVA is a water-soluble synthetic polymer (a fancy word for plastic that readily binds itself to water molecules). You’ll find it on the ingredient list of virtually every laundry or dishwasher pod and every laundry sheet or strip. PVA has excellent barrier properties, so it’s good at holding together liquids and other squishy stuff, like soap. It’s also really good at dissolving. That’s why it vanishes in our washing machines and dishwashers. But does it really disappear? “When you stir a spoonful of sugar or salt into water, it dissolves, but is it gone?” Cohen asks. “Take a taste and you have your answer. It’s the same with PVA.”

The dissolved PVA slides right down the tubes and off it goes to the treatment plant with your dirt, suds, and wastewater. What happens next depends on who you ask.

According to the American Cleaning Institute, PVA polymers are “fully biodegraded by microorganisms in water treatment facilities and the environment.” But Cohen, a slew of other leading advocates for clean oceans, and this 2021 study in The International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health which looks at PVA degradation U.S. wastewater treatment plants, say that is simply not the case. “There is a serious lack of unbiased research on the human and environmental health effects of PVA,” says Cohen because existing research was funded by companies with biased interests. “We do, however, know that PVA has been found in human breast milk and in fish, which indicates that it does not simply vanish in wastewater treatment plants. It’s making its way into our bodies and our environment.”

Plastic Pollution Coalition, as well as many other advocacy groups like like Plastic Oceans, Beyond Plastics, and 5 Gyres, contend that we simply don’t know enough about the effects of PVA—which is why the groups have come together to call on the EPA to conduct an independent study to figure it out. “We need the EPA to take swift and urgent action to study the full ecological and health impacts of PVA in order to best protect people and our planet from potential harm,” says Cohen. The group has currently collected close to 23,000 signatures on a petition to get the EPA to conduct extensive tests on PVA biodegradability and its potential impact on the environment and human health. They want a few thousand more. You can add your name here.

Laundry Soaps That Are Truly Plastic-Free

So what’s an environmentalist to do? First, avoid buying detergent in plastic containers. Second, check the ingredient list and if you see a lot of long, chemical-ish words, be suspicious. These things are bad: optical brighteners, chlorine, formaldehyde, synthetic nonylphenol ethoxylates, phosphates, phthalates. Third, if you have a refill shop near you, BYO containers and support it. We need the concept of refill shops to catch on in U.S.

Cohen helped me come up with a few green detergent ideas, all of which are quite affordable.

DIY Laundry Soap

Combine 14 ounces of washing soda, 14 ounces of borax, or baking soda, with 4.5 ounces of natural castile soap flakes. Store the mixture in a sealed glass jar. Use one to three tablespoons per load, depending on size.Cost: about .10 per load.

Soap Nuts

I’ve been using these for several weeks with good results. Just put five to seven nuts (which are really berries) into the included muslin sack and toss in the wash. The shells contain saponin, a natural soap which releases into the water. Soap nuts don’t generate a lot of suds (because they lack the chemical foaming agents we’re used to) and they’re not for tough stains. But for regular use, they’re pretty cool. You can use soap nuts five to eight times before the saponin wears off. Compost the spent nuts and replace with new ones. I’ve been adding a few drops of lavender essential oil to the bag to give my laundry a light fragrance—the nuts alone are odorless.Cost: about .23 per load.

Meliora Laundry Powder Detergent

This powder also gets my thumbs up. Made with non-toxic ingredients and shipped in curbside recyclable packaging, it comes in several all-natural scents. Meliora also makes a Soap Stick Stain Remover, which I use to rub any tough spots before washing.Cost: about .23 per load

More Sustainable Laundry Tips

Choosing a non-toxic, plastic-free detergent isn’t the only way to green up your laundry process. Here are some other tips.

Wear Clothes Longer

Don’t mindlessly toss clothes into the hamper after a wear. Ask yourself if those jeans really need washing, or can you fold them up and wear them again?

Turn Clothes Inside Out Before Washing

This will make your clothes last longer by protecting colors from premature fading and preventing snags during laundering.

Fill the Machine

Say no to half loads; they waste water and energy.

Use Cold Water

Unless your clothes are really dirty, go for the cold wash. You’ll save money and energy, and your clothes will last longer and shed fewer microfibers, which is another environmental concern.

Air Dry

Like cold-washing, air drying will also save you money and energy, even if you partially air dry and then finish it off in the dryer to release wrinkles.

Skip the Dryer Sheets

Yep, they contain PVA, too. I’ve been using wool dryer balls for over a year and they do a fine job of releasing wrinkles, fluffing things up, and reducing (most, but not always all) static.

Avoid Dry Cleaning

You know that distinctive smell that hits you when you walk into a dry cleaner? Those are chemicals. Most dry cleaners use a host of toxic chemicals and petroleum-based solvents that can be harmful to humans and the environment.

Kristin Hostetter is the head of sustainability at Outside Interactive, Inc. and the resident sustainability columnist on Outside Online.

World Ocean Day: How much plastic is in our oceans?

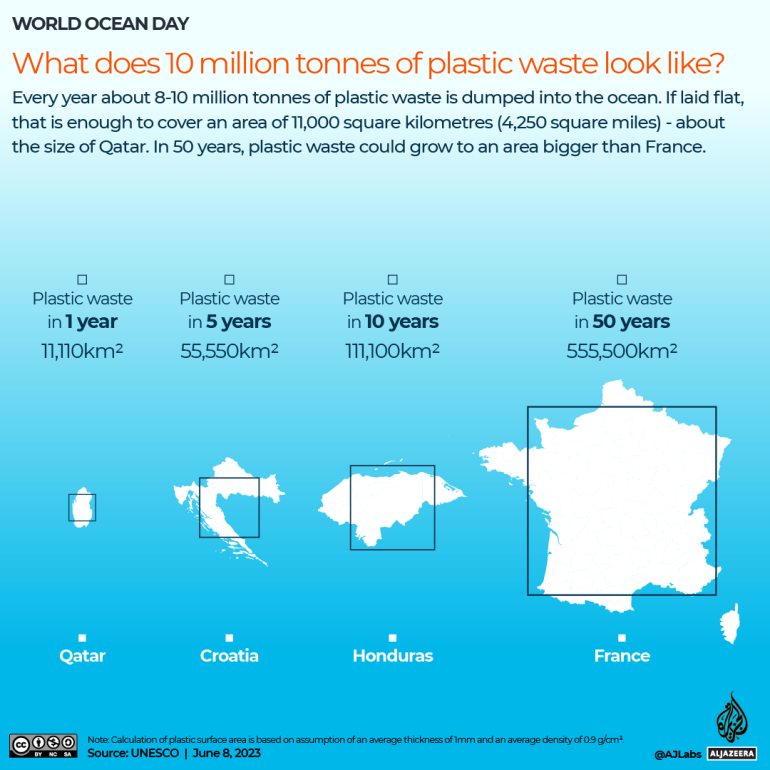

According to UNESCO, 8-10 million tonnes of plastic are released into the sea every year. On World Ocean Day, Al Jazeera visualises what that looks like.Every year, about 400 million tonnes of plastic products are produced around the world. About half are used to make single-use items such as shopping bags, cups and packaging material.

Of these plastics, an estimated 8 million to 10 million tonnes end up in the ocean each year. If flattened to the thickness of a plastic bag, that is enough to cover an area of 11,000sq km (4,250sq miles). That is about the size of small countries like Qatar, Jamaica or the Bahamas.

At this rate, over the course of 50 years, plastic waste could grow to an area bigger than 550,000sq km (212,000sq miles) – about the size of France, Thailand or Ukraine.

To raise awareness about the importance of the ocean and promote its sustainable use and protection, the United Nations designated every June 8 as World Ocean Day.

(Al Jazeera)

How does plastic end up in the ocean?

Plastics are the most common form of ocean litter, comprising 80 percent of all marine pollution. Most plastics that end up in the ocean come from improper waste disposal systems that dump rubbish in rivers and streams.

Plastics in the form of fishing nets and other marine equipment are also dumped into the ocean by ships and fishing boats.

Besides plastic bags and containers, tiny particles known as microplastics also make their way into the ocean. Microplastics, which are less than 5mm (one-fifth of an inch) in length, are a major environmental concern because they can be ingested by marine life and cause harm to both animals and humans.

An estimated 50 trillion to 75 trillion pieces of microplastics are in the ocean today.

(Al Jazeera)

While research on the health effects of human consumption of microplastics is limited, some studies have indicated that microplastics can accumulate in organs such as the liver, kidneys and intestines. There are concerns that microplastic particles could potentially lead to inflammation, oxidative stress and cellular damage.

“These little particles in the ocean were breaking into little pieces and being consumed by the wildlife living there at an almost unimaginable scale. The main problem is that pieces of plastic contain toxic chemicals and these chemicals are already known to interfere with human hormones and animal hormones. They may cause the accumulation of toxins in the body that may lead to ill effects over time,” science writer and author Erica Cirino told Al Jazeera’s The Stream programme.

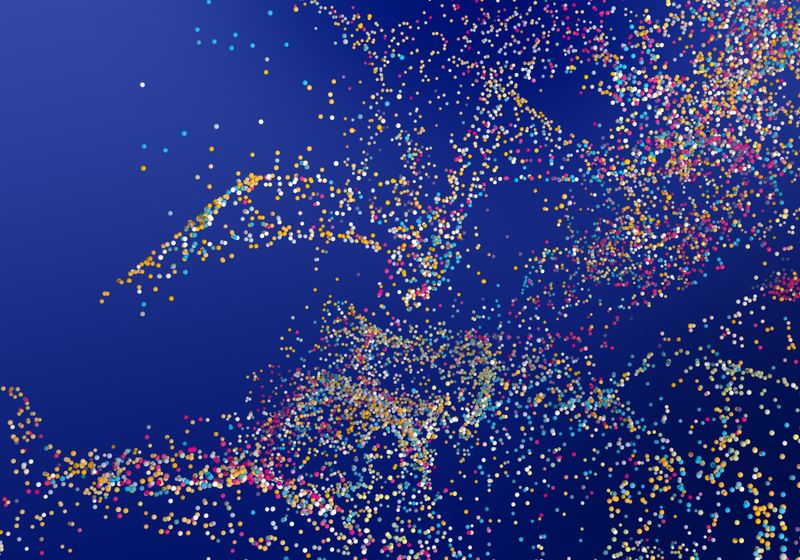

Which countries are the source of the most plastic in the ocean?

According to a 2021 study published by Science Advances research, 80 percent of all plastics found in the ocean comes from Asia.

The Philippines is believed to be the source of more than a third (36.4 percent) of all plastic waste in the ocean followed by India (12.9 percent), Malaysia (7.5 percent), China (7.2 percent) and Indonesia (5.8 percent).

These amounts do not include waste that is exported overseas that may be at higher risk of entering the ocean.

(Al Jazeera)

What makes plastics so dangerous for the environment?

Plastics are synthetic materials made from polymers, which are long chains of molecules. These polymers are typically derived from petroleum or natural gas.

The main problem with plastics is that they do not easily biodegrade, which means they can persist in the environment for hundreds of years, causing serious pollution problems.

Plastics that find their way into the ocean end up floating on the surface for a long time. Eventually, they sink to the bottom and get buried in the seafloor.

Plastics on the surface of the ocean represent 1 percent of the total plastics in the ocean. The other 99 percent are microplastic fragments far below the surface.

Plastic bottles, wooden planks, rusty barrels and other rubbish clog the Drina river near the eastern Bosnian town of Visegrad on May 25, 2023 [Eldar Emric/AP]

Glass, aluminum, paper? What to know about alternatives to plastic

The list of plastic substitutes seems to be growing longer by the day as companies come up with novel products such as cling wrap made from potato waste, seaweed-based food wrappers, and cassava starch bags.That’s in addition to efforts to package more products in everyday alternative materials, such as glass, metal and paper.Yet, the world’s plastic pollution problem has continued to worsen.Work is underway to create the first global treaty to reduce plastic pollution. But experts say achieving that goal will probably involve, in part, developing better substitutes — a challenge that has appeared to vex many environmentalists and sustainability researchers.That’s because it hasn’t been easy to replace plastic, a ubiquitous material that’s inexpensive, robust and versatile.“Plastics need to get fixed,” said Michael Shaver, director of the Sustainable Materials Innovation Hub at the University of Manchester. “But doing that by simply switching to another material without considering the consequences of that is where that’s dangerous.”There are 21,000 pieces of plastic in the ocean for each person on EarthUnderstanding the plastics problemConventional plastics are made from fossil fuels. But the problem with plastics, Shaver said, is less about the material and more about what is done with them at end of life.“We haven’t treated them with care,” he said. “The lack of waste management of those materials is what creates the problem.”The little-known unintended consequence of recycling plasticsMuch of the plastic that is produced does not get recycled. “That’s not because people aren’t putting the right thing in their bins,” said Melissa Valliant, communications director for the Beyond Plastics advocacy organization. “It’s because so much of our plastic products just cannot be recycled.”In the United States, recycling facilities typically can only effectively process No. 1 and 2 plastic. One peer-reviewed study of a recycling facility in the United Kingdom also found that 6 to 13 percent of the plastic processed there could end up being released into water or the air as microplastics.The search for plastic alternativesHowever, other packaging materials can also come with recycling challenges, and some have disadvantages when compared to plastic.“It’s not that any of those solutions is bad, but there’s not a panacea,” Shaver said. “There’s not a single solution which works for everywhere.”Here’s a look at how some common plastic alternatives measure up:Glass is made of natural materials such as sand, soda ash and limestone that are melted at high temperatures. Unlike plastic, experts say, glass is often easily reused and can be recycled many times without degrading in quality.But glass is heavy, so moving it over long distances can drive up transportation costs, said Muhammad Rabnawaz, an associate professor in the School of Packaging at Michigan State University. The material can also be more prone to breaking than plastic, aluminum and paper.And making and recycling glass are both energy-intensive processes, experts say. “Until we can couple that glass recycling to renewable energy, we’re at a risk of trading a waste problem for an energy problem,” Shaver said.Glass could, however, be the preferred choice in refill systems where transportation distances are short, he added.Making virgin aluminum, which involves mining minerals such as bauxite, can be environmentally destructive and energy-intensive. But it has the benefit of being lightweight and recyclable.“Aluminum is very difficult to make from the raw materials, so you must recycle it; otherwise there is no benefit,” Rabnawaz said. Recycling of aluminum cans, for example, is estimated to save 95 percent of the energy required to make the same amount of aluminum from its virgin source.But aluminum recycling, which involves melting down the material, can have its complications. Like glass, it can be recycled many times and still maintain its integrity, but aluminum cans are typically manufactured with a thin plastic coating on the inside that acts as a protective lining, Shaver said.“What happens to that is that when you melt the aluminum down, it gets burned, so we’re actually burning the plastic bit and then we’re recycling the container,” he said.Paper, which is recyclable, is generally thought of as one of the most environmentally sustainable materials, said Laszlo Horvath, an associate professor and director of the Center for Packaging and Unit Load Design at Virginia Tech.But recycling paper is an extremely environmentally damaging process, Horvath said. “It requires a lot of chemicals, it requires a lot of energy, a lot of water,” he added. Similar to plastic, it can be challenging to maintain the quality of paper after it’s been recycled, Shaver said.Though a growing number of companies are finding more ways to use paper to package their products, experts say the material can fall short in some areas compared to plastic or aluminum. When it comes to packaging liquids, in particular, paper often isn’t a good alternative material, Horvath said.It’s also difficult to recycle paper-based beverage containers, Rabnawaz added.Bioplastics, biodegradables and compostablesFirst, experts say, it’s critical to understand what these terms mean. Using the label “bioplastic” or “biopolymer” typically indicates a material’s source is something biological, which can include food products, food waste or agricultural waste, Shaver said.“Bioplastics do not necessarily mean biodegradable or compostable,” he said.For consumers, it can also be hard to tell whether products marketed as biodegradable or compostable really are, he said.“Many things are industrially biodegradable or industrially compostable, not biodegradable in the environment or in the ocean or home composting,” he said. And because there can be different accreditations for products, that increases the risk of greenwashing, he added.Regardless of the material, the key, Shaver said, is to think about what happens to packaging after people are done with it.“It does not matter if something is recyclable, if it’s not recycled,” he said. “It does not matter if something is biodegradable, if it is not biodegraded. It does not matter if something is reusable, if it is not reused.”

Nanoplastic ingestion causes neurological deficits

Microplastics, or plastic particulates measuring less than five micrometers, are a growing environmental concern. These particulates disrupt reproduction, immune cell and microbiome composition in the gut, and neural and endocrine function in aquatic species and laboratory animals.1-4 Now, a new study published in Cell Reports suggests that the smaller the plastic, the greater the problem.5According to Chao Wang, an immunologist at Soochow University and coauthor of the study, feeding mice nanoplastics induced a greater overall immune response in their guts than feeding mice larger microplastics. This supports previous research showing size-dependent differences in how nanoparticles interact with cells and instigate responses from them.6Wang and his team found that nanoplastics, defined as being less than 500 nanometers in size, are more readily phagocytosed by macrophages compared to microplastics, which measure up to five micrometers. The smaller sized particulates induced a greater degree of lysosomal damage in these cells and resulted in production of the proinflammatory cytokine interleukin 1 beta (IL-1β) both in vitro and in the intestines of mice following one week of daily oral administration of the plastic. Using single-cell sequencing, Wang and his colleagues identified a population of IL-1β-producing macrophages in the intestines of nanoplastic-fed mice.Recent studies have shown that inflammatory responses in the intestines affect the brain, so Wang and his team next assessed the gut-brain axis. After two months of daily ingestion of nanoplastics at the estimated human consumption dose, nanoplastic-exposed mice exhibited reduced cognition and short-term memory as assessed by standard neurological assessments such as the open-field test, novel object recognition assay, and the Morris water maze. These plastic-fed mice also had more activated microglia and astrocytes as well as Th17-differentiated T cells than nontreated mice.Wang and his colleagues also observed elevated IL-1β in the brains of plastic-fed mice, but did not find IL-1β-producing cells in the brain, which suggested that these effects resulted from IL-1β-producing macrophages in the gut. “All these changes associated with brain function damage,” Wang said.Neurological effects from the ingestion of microplastics have been abundantly documented in marine species2,7,8 as plastic pollution in water ways is an outstanding problem. “I didn’t know the enormity—how big this problem was—until I started working on it about three years ago,” said Ebenezer Nyadjro, an oceanographer at Mississippi State University and data manager at the National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI), who was not involved with the study. “The long-term effect is if this is not controlled—if we keep dumping plastics into the water bodies, they break down into microplastics; they have an impact on those fisheries; and as studies have shown, they bioaccumulate up to higher organisms and humans—there will be impacts on us as well.”This observation has been echoed with recent reports of microplastics in human tissues,9 underscoring the importance of Wang’s findings.However, even after two months of daily nanoplastic ingestion, cognitive function and short-term memory impairments were mitigated by blocking IL-1β using either a monoclonal antibody or chemical inhibitor, and more promisingly, by cessation of nanoplastic exposure. One month after Wang and his team stopped feeding mice nanoplastics, they performed as well as nontreated mice in neurological assessments. “It’s showing this effect is not permanent but can be rescued. So, it’s showing one more reason to fix the plastic pollution worldwide,” Wang said.ReferencesHarusato A, Seo W, Abo H, Nakanishi Y, Nishikawa H, Itoh Y. Impact of particulate microplastics generated from polyethylene terephthalate on gut pathology and immune microenvironments. iScience. 2023;26(4):106474. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2023.106474.Torres-Ruiz M, de Alba González M, Morales M, et al. Neurotoxicity and endocrine disruption caused by polystyrene nanoparticles in zebrafish embryo. Science of the Total Environment. 2023;874:162406. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.162406.Mattioda V, Benedetti V, Tessarolo C, et al. Pro-inflammatory and cytotoxic effects of polystyrene microplastics on human and murine intestinal cell lines. Biomolecules. 2023;13(1):140. doi: 10.3390/biom13010140Merkley SD, Moss HC, Goodfellow SM, et al. Polystyrene microplastics induce an immunometabolic active state in macrophages. Cell Biology and Toxicology. 2022;38(1):31-41. doi:10.1007/s10565-021-09616-xYang Q, Dai H, Cheng Y, et al. Oral feeding of nanoplastics affects brain function of mice by inducing macrophage IL-1 signal in the intestine. Cell Reports. 2023;42(4). doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2023.112346Jiang W, Kim BYS, Rutka JT. Chan WCW. Nanoparticle-mediated cellular response is size-dependent. Nature Nanotechnology. 2008;3 https://doi.org/10.1038/nnano.2008.30Hamed M, Martyniuk CJ, Naguib M, Lee JS, Sayed AEH. Neurotoxic effects of different sizes of plastics (nano, micro, and macro) on juvenile common carp (Cyprinus carpio). Frontiers in Molecular Neuroscience. 2022;15:1028364. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2022.1028364.Aliakbarzadeh F, Rafiee M, Khodagholi F, Khorramizadeh MR, Manouchehri H, Eslami A, et al. Adverse effects of polystyrene nanoplastic and its binary mixtures with nonylphenol on zebrafish nervous system: From oxidative stress to impaired neurotransmitter system. Environmental Pollution. 2023;317:120587. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2022.120587.Amato-Lourenço LF, Carvalho-Oliveira R, Júnior GR, dos Santos Galvão L, Ando RA, Mauad T. Presence of airborne microplastics in human lung tissue. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2021;416:126124. Doi:10.1016/j.jhaxmat.2021.126124

Boyan Slat: Humanity is addicted to plastic, but we can still keep it out of our oceans

The world is finally getting serious about plastic pollution.Next week, delegates from U.N. member states will gather in Paris to debate the shape of what some hope will become the plastic-pollution equivalent of the Paris Climate Agreement.There is no time to waste. Plastic is one of the biggest threats our oceans face today, causing untold harm to ecosystems, tremendous economic damage to coastal communities and posing a potential health threat to more than three billion people dependent on seafood.The U.N. Environment Program has put forward a proposal to keep plastics in circulation as long as possible through reuse and recycling. Some activists and scientists advocate capping and reducing plastic production and use.Plastic pollution in Las Vacas River, Guatemala.The Ocean CleanupA barrier guards a river from plastic in Guatemala.The Ocean CleanupI share the desire for real long-term change, and all proposals should be considered. But if we are to halt the flow of plastic into our oceans in the near future, then we must focus our actions on the polluting rivers that carry most of it there.In 2011, when I was 16, I went scuba diving during a family holiday in Greece, excited to experience the eternal beauty of our ocean and its wildlife.I saw more plastic bags than fish. It was a crushing disappointment. I asked myself, “Why can’t we just clean this up?”Naïve? Perhaps. But I set out to try. By 2013 I had founded The Ocean Cleanup, a nonprofit funded by donations and a range of philanthropic partners with the mission to rid the oceans of plastic.An Interceptor machine collecting plastic in a river in Los Angeles County.The Ocean CleanupIt made sense to target what is perhaps the most glaring symbol of our oceanic plastic problem, the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, an expanse in the North Pacific Ocean more than twice the size of Texas where bottles, buoys and other plastic refuse accumulates because of converging currents.Working in harsh oceanic conditions is a challenge, and we have encountered our share of setbacks. What kept us going were the scenes our crews encountered at sea: dissected fish whose guts were full of sharp plastic fragments, sea turtles entangled in abandoned fishing nets.Eventually, in 2021, we managed to get our system to work. Two boats pull a U-shaped barrier — our latest version is almost a mile long — through the water at slow speed, which funnels plastic into a collection area. The waste is pulled out, taken to shore and recycled. We take great care to ensure that our cleanup efforts don’t harm the marine ecosystem. Images of heaps of plastic being pulled from the ocean have led to accusations — never substantiated — that they were staged. But the tons of plastic that we gather are all too real.We are still at the pilot stage, but by our estimates we’ve removed more than 0.2 percent of the plastic in the patch so far and our systems are only getting better. We have a long way to go, but we are making progress.Cleaning up ocean garbage patches is critical. But if we don’t also stop more plastic from flowing into the oceans, we will never be able to get the job done.

Powerful art installation at Chennai beach reflects grim reality of marine pollution

The plastic waste was retrieved from the ocean at Chennai’s Besant Nagar Beach. (Credits : Twitter)It was revealed to mark the Mega Beach Clean-Up programme on May 21.The sad reality of marine pollution not only shows the extent of the problem in our environment but also serves as a stark reminder of the grave threat to our biodiversity. In an effort to promote awareness about the importance of keeping beaches clean and mitigating the influx of plastic into the ocean, authorities in Chennai took a proactive step. They established an art installation at Besant Nagar beach, constructed entirely from ocean plastic, resembling a colossal fish.IAS officer Supriya Sahu posted a video on Twitter and wrote: “We have put up this installation made with plastic waste retrieved from the ocean at Besant Nagar Beach in Chennai to mark the Mega Beach Clean-up programme organised today. It not only portrays the sad reality of pollution in our oceans but also raises an alarm about the serious threat to marine biodiversity.”We have put up this installation made with plastic waste retrieved from the ocean at Besant Nagar Beach in Chennai to mark the Mega Beach Clean up programme organised today. It not only portrays the sad reality of pollution in our oceans but also raises an alarm about the serious… pic.twitter.com/Vn0a7jhuGj— Supriya Sahu IAS (@supriyasahuias) May 21, 2023The art installation acted as a compelling symbol, shedding light on the critical importance of environmental conservation. It was established ahead of a countrywide beach clean-up campaign on May 21, coinciding with the first day of the third G20 Environment and Climate Sustainability Working Group Meeting. This synchronized endeavor aimed to tackle the urgent problem of plastic pollution.Since the day the video was posted, it has amassed around 70 thousand views. Commenting on the video, a user from Nilgiris raised the concern about the place saying, “Dear Ma’am, can something similar be done in Nilgiris as well? Plastic waste strewn on the roadside, garbage bins lying overturned everywhere – certainly not a pleasant sight to see. I believe the authorities need to renew their vigour to keep Nilgiris plastic free.”Dear Ma’am, can something similar be done in Nilgiris as well? Plastic waste strewn on the road side, garbage bins lying overturned everywhere – certainly not a pleasant sight to see. I believe the authorities need to renew their vigour to keep Nilgiris plastic free!#Nilgiris— vivek (@hvivekw) May 21, 2023Another user agreed and commented: “Yes. We have beaches, mountains, rivers, lakes, waterfalls but nothing is clean everything is polluted. Only government cannot prevent this. People come forward to clean our environmental. Only public+private+people make this happen.”Yes.we have beaches, mountains, rivers,lakes, waterfalls but nothing is clean everything is polluted. Only government cannot prevent this.people come forward to clean our environmental.Only public+private+people make this happen.— Rahul (@rahul_space6) May 21, 2023“An Ocean Emergency has already been declared by the UN. It is about time India seriously invested in Inland fishery-with the multiple benefits of saving wetlands/ponds/lakes etc, increasing nutrition incomes ++. As a proactive bureaucrat, please take the lead Ms Sahu,” wrote another.top videosAn “Ocean Emergency “ has already been declared by the UN. It is about time India seriously invested in Inland fishery-with the multiple benefits of saving wetlands/ponds/lakes etc, increasing nutrition+incomes ++. As a proactive bureaucrat, please take the lead Ms Sahu.— Lalitha Kumaramangalam (@kumaramangalaml) May 21, 2023What do you think about this initiative?

About the AuthorBuzz StaffA team of writers at News18.com bring you stories on what’s creating the buzz on the Internet while exploring science, cricket, tech, gender, Bollywoo

Recycling plants release microplastics into wastewater

An unsettling report released barely a year ago painted a grim picture of the plastics industry—only about 5 percent of the 46 million annual tons of plastic waste in the US makes it to recycling facilities. The number is even more depressing after realizing that is roughly half of experts’ previous estimates. But if all that wasn’t enough, new information throws a heaping handful of salt on the wound: of the plastic that does make it to recycling, a lot of it is still released into the world as potentially toxic microplastics.

According to the pilot study recently published in the Journal of Hazardous Materials Advances focused on a single, modern facility, recycling plants’ wastewater contains a staggering number of microplastic particles. And as Wired explained on Friday, all those possibly toxic particulates have to go somewhere, i.e. potentially city water systems, or the larger environment.

The survey focusing on one new, unnamed facility examined its entire recycling process. This involves sorting, shredding, and melting plastics down into pellets. During those phases of recycling, however, the plastic waste is washed multiple times, which subsequently sheds particles smaller than 5 millimeters along the way. Despite factoring in the plant’s state-of-the-art filtration system designed to capture particulates as tiny as 50 microns, the facility still produced as many as 75 billion particles per cubic meter of wastewater.

[Related: How companies greenwash their plastic pollution.]

The silver lining here is that without the filtration systems, it could be much worse. Researchers estimated facilities that utilized filters cut down their microplastic residuals from 6.5 million pounds to around 3 million pounds per year. Unfortunately, many recycling locations aren’t as equipped as the modern plant used within the study. On top of that, the team only focused on microplastics as small as 1.6 microns; particles can get so small they actually enter organisms’ individual cells. This implies much more plastic escapes these facilities than previously anticipated.

“I really don’t want it to suggest to people that we shouldn’t recycle, and to give it a completely negative reputation,” Erina Brown, a plastics scientist at the University of Strathclyde, told Wired. “What it really highlights is that we just really need to consider the impacts of the solutions.”

Most experts agree that the most important way to minimize coating the entire planet in microplastics is to focus on the larger issue—reducing society’s reliance on plastics in general, and pursuing alternative materials. In the meantime, recycling remains an important part of sustainability, as long as both facilities do everything they can to minimize microscopic waste.

Wanted: Lost crab traps. Reward: $5

Article body copy

Crab traps work a bit like Roach Motels: crabs crawl in, but they don’t crawl out. That’s good news for crab fishers’ chances of pulling in a good catch, but when traps get lost at sea, they become a menace to all sorts of animals.

With no one there to retrieve them, the traps continue to fish, says Ryan Bradley, head of the Mississippi Commercial Fisheries United, a nonprofit fishermen’s organization. “Marine life gets into the trap. Eventually, they can’t eat so they die, and then other marine life becomes attracted to it. They get into the trap, and they die. It just becomes this awful cycle of death.”

Derelict crab traps harm wildlife and disrupt other fishers, especially shrimpers. Bulky crab traps get caught in shrimping nets, tearing them open or blocking them from catching shrimp. Frustrated shrimpers, with nowhere to put the smelly traps, generally just throw them back, continuing the cycle.

But a group in Mississippi has found a solution: paying shrimpers a US $5 bounty to collect and recycle derelict crab traps. In just three years, the program has removed almost 3,000 crab traps from Mississippi waters. Crab traps are tagged, and those that are still in good condition are returned to their owners, while traps that are too broken down are recycled.

It’s a real win-win. Wildlife is safer, the water is cleaner and, says Bradley, who cofounded the program, there’s been a clear trend that shrimpers are encountering fewer traps.

The group, which includes the fishers’ association, Mississippi State University, the Mississippi-Alabama Sea Grant Consortium, and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Marine Debris Program, recently published a paper expanding on the project’s accomplishments.

Alyssa Rodolfich, a graduate student with Mississippi State University, knows the central-northern Gulf of Mexico well. She grew up in the area fishing with her dad, a charter boat captain. But she hadn’t thought much about derelict crab traps until she started working with the incentive program as an intern.

“I didn’t realize how big of a problem it was until I was on the cleaning-up end of it, after a few months of removing, like, 200 crab traps at a time,” she says. “It was heavy and gross, and the amount of by-catch in the traps was a lot.”

At the same time, she was talking with shrimpers, learning about the problems derelict traps pose for them. Now working as the program’s manager, Rodolfich says it’s gratifying to see the results. “It feels like a big accomplishment, not just to see the amount of debris that’s been removed but also to see the change in attitude and behavior,” she says.

The incentive works like a bottle-redemption program. Participating shrimpers register for the program, document the traps they collect, and tag them before turning them in to a redemption site and documenting the drop-off to claim the reward.

“It’s not uncommon for our guys to turn in five, 10, 15 of these traps from one multiday shrimping trip,” Bradley says.

Chloé Dubois, the cofounder and head of the British Columbia–based Ocean Legacy Foundation, a nonprofit focused on marine debris, calls it “a great success story.” Her organization was not involved with the project but is advocating for a similar program to be piloted in British Columbia.

Dubois says redemption programs have historically been very successful at diverting waste products at the end of their life cycle. But in the ghost fishing and marine debris sphere, she says, the Mississippi program is a pioneer. “There aren’t many examples of programs like this,” she says.

Partnering with the fishing industry on the incentives and using the program to gather data on the numbers and locations of traps while also removing marine debris further sets the program apart, she says.

Bradley says his group has fielded calls from other communities hoping to develop similar programs, though he notes that some states have legal issues that make it difficult for fishers to collect traps that aren’t their own.

In the meantime, the Mississippi program is growing and expanding. With a recent grant from NOAA, they’re starting a new pilot project—paying shrimpers to collect all the other stuff they find littering the Gulf.

“We’ve seen everything from washing machines to toilets to tires to plastic bags,” says Bradley. “The other day, one guy told me he pulled up a shopping cart. So these are the types of things we want to get out of our marine environment.”

Lobbyists kill Virginia climate change bills

Luca Powell

The proposal was simple.Wary of mounting plastic in Virginia’s bays and waterways, a state senator from Roanoke wanted to allow localities to ban plastic bags. For years, the Environmental Protection Agency has known that fewer than 10% of plastic bags get recycled and that most wind up in the ocean, slowly becoming decomposing plastic that finds its way into fish and drinking water.The senator, John Edwards, did not expect the pushback. In a committee meeting during the legislative session, five lobbyists came up to speak against the bill.One, Mike Carlin, implored the committee to give recycling a chance.“I believe that SB933 (Edwards’ bill) sends the wrong message to this industry, and is a deterrent to investment in our state, by banning plastic which can be recycled,” said Carlin, a lobbyist with the national Coalition for Consumer Choice.

People are also reading…

Similar showdowns take place several times a day during Virginia’s legislative session. Despite the developing climate crisis, bills designed to curb pollution and emissions find fierce opposition in the growing, well-financed lobbies that have put down deep roots in the commonwealth.Sometimes, the lobbyists represent companies that outwardly market themselves to customers as environmentally friendly.This session, legislators proposed a number of ideas to make Virginia more green and to make it safer from harmful chemicals.Del. Kathy Tran, D-Fairfax, proposed a bill to ban the use of coal tar sealants — the thick, black goop used to coat asphalt on driveways and parking lots.The sealants contain toxic compounds — polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, or PAHs — that leak into the environment over time and have been found in Virginia’s waterways, according to reporting from Virginia Commonwealth University’s Capital News Service.Del. Nadarius Clark, D-Portsmouth, proposed a bill to study whether Virginia’s highly active plastics industry was shedding “microplastics” into the state’s drinking water.Another bill proposed by Edwards would have required water companies to tell the public when their drinking water was found to have problematic levels of per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS, the “forever chemicals” that have been shown to harm humans and especially children.The bill was supported and presented by Chris Pomeroy, legal counsel for the Virginia Municipal Drinking Water Association.One lobbyist spoke in support. “This is just asking for a community’s right to know if their water’s safe,” said Pat Calvert with the Virginia Conservation Network.Carlin spoke against the bill, this time on behalf of the Virginia Manufacturers Association, another prominent industry lobby.He was joined by a representative from the American Chemistry Council, who said that telling Virginians when “forever chemicals” were found in their drinking water would cause “undue alarm.”The bill was tabled by the committee, which means it was killed. The votes to squelch the bill came from Dels. Michael Webert, R-Fauquier; Chris Runion, R-Rockingham; Rob Bloxom, R-Accomack; Tony Wilt, R-Rockingham; and Buddy Fowler, R-Hanover. All received A ratings from Carlin’s organization.Tran’s sealant legislation also failed, as did Clark’s bill to study plastics.Carlin did not reply to several requests for comment, nor did Brett Vassey, president of the Virginia Manufacturers Association.Unsurprisingly, money is the big differentiator between the environmental and industrial lobbies. Most of the former are nonprofits, for which it is illegal to make political donations.Trade groups, law firms and big Virginia companies like Dominion Energy have no such restrictions. All give freely to Democrats and Republicans alike, although donation data from the Virginia Public Access Project shows that Republicans benefit far more from industry-aligned lobbying groups.For example, the Virginia Retail Federation, a lobby that represents Virginia small businesses, moved over $50,000 in campaign donations in 2022. The group gave mostly to Republicans.“They’re lobbying year-round for their priorities, which is frustrating because we in the environmental space don’t have those kinds of resources,” said Connor Kish, legislative director with the Virginia chapter of the Sierra Club.

Plastic breaking down into tiny particles that float like dust in the airA short legislative session sharpens the point. Industries can simply hire more lobbyists than environmental groups, outgunning them in a game defined by time and access.In the most recent legislative session, 1,030 lobbyists had registered with the state’s ethics board. The number ticks higher every year.

Virginia Public Access Project

Meanwhile, lobbyists are also writing their own legislation to beat back bans from environmentalists.In 2022, Washington Gas pushed a bill that would ban Virginia localities from zoning buildings without natural gas hookups. Natural gas primarily is composed of methane, which accounts for about 12% of all greenhouse gas emissions.The bill came through Terry Kilgore, a Republican in the House of Delegates whose campaign has received $22,000 from Washington Gas across his 30-year political career. VPAP data shows the largest donation — a $6,000 check — came the year he put the bill forward.In a statement shared by his office, Kilgore said, “The impetus for filing House Bill 1257 was to preserve fuel choice and ensure a family’s gas stove cannot be taken away.”

A1 Extra! Luca Powell discusses the plastic polluting local waterways – A1 Extra is presented by 8@4 | A1 ExtraA version of Kilgore’s bill ultimately passed after it was reworked last August in a special session.“Lobbyists have a tremendous influence in this place,” said Edwards, the Roanoke senator who sponsored the plastics and PFAS bills. “The General Assembly is free to make their own decision, but they’re heavily influenced.”Edwards’ plastics bill was nixed by lobbyists from the Virginia Retail Federation. The lobby represents small and large businesses across the state, including Dominion, Home Depot and Target — companies that market their environmental responsibility to their customers.It was also opposed by the Virginia Food Industry Association, which is funded by donations from such grocers as Publix and Wegmans. Publix actively tracks the number of plastic bags it saves on its website. Wegmans committed to eliminating plastic bags in its Virginia stores last summer. Melissa Assalone, director of the Virginia Food Industry Association, did not return a request for comment on the lobby’s position against the bill.Ultimately, Edwards’ bill did not pass either, as it apparently failed to persuade key Democrats on the committee, including Lynwood Lewis, the committee chair.Lewis represents Accomack and Northampton counties on the state’s Eastern Shore. In his 18-year legislative career, he has received $10,000 in campaign donations from Troutman Pepper, another of the five lobbying firms that initially pushed against the plastics legislation. He also received $6,250 in campaign donations from the Virginia Retail Federation.Lewis voted “nay” on the bill.

Luca Powell (804) 649-6103lpowell@timesdispatch.com@luca_a_powell on Twitter

0 Comments

#lee-rev-content { margin:0 -5px; }

#lee-rev-content h3 {

font-family: inherit!important;

font-weight: 700!important;

border-left: 8px solid var(–lee-blox-link-color);

text-indent: 7px;

font-size: 24px!important;

line-height: 24px;

}

#lee-rev-content .rc-provider {

font-family: inherit!important;

}

#lee-rev-content h4 {

line-height: 24px!important;

font-family: “serif-ds”,Times,”Times New Roman”,serif!important;

margin-top: 10px!important;

}

@media (max-width: 991px) {

#lee-rev-content h3 {

font-size: 18px!important;

line-height: 18px;

}

}