This story is a collaboration between VICE World News and The Fuller Project.DANDORA, Kenya– As Winnie Wanjira rifles through mountains of waste at the Dandora dump in Nairobi, it’s not the discarded needles that most bother her. Nor the metal scraps that could shred her skin like paper. It’s not even the hot sun that beats down on the rancid rubbish, making the 36-year-old feel so dizzy she struggles to fill her sack with plastic bottles. Today, the mother of six is anxious about her period. It’s heavy, she says. So heavy she spent the last two days lying down in her windowless, single-bedroom home, unable to move. “The bleeding… is no joke,” she tells The Fuller Project and VICE World News. “I cannot come to work, I cannot go anywhere.” Joyce Wangari (left) and Winnie Wanjira are fighting to protect waste pickers’ rights. Now, on the third day, she’s back, hoping the jumper tied around her waist will cover any stains. “And it’s, like, black, not even the normal colour of periods,” she says. “That place… It kills. It really kills.”As far back as 2007, the United Nations Environment Program warned that Dandora posed a serious health threat to those working and living nearby. Yet while it is understood that exposure to the toxic chemicals found on dumpsites can result in cancer, respiratory problems and skin infections, scientists and environmental campaigners say relatively little attention has been paid to their impact on the reproductive health of waste pickers, who are often women. Materials such as plastic and e-waste contain a cocktail of chemicals that studies show can disturb the body’s hormone systems. As ever-higher volumes of trash continue to end up in landfills, informal workers like Wanjira will be on the front lines of what scientists are calling an emerging issue of global concern.Most waste pickers handle trash without gloves or masks and often live near or on the dumpsites, which intensifies their exposure to health risks.For years, acrid smoke has billowed across this sprawling dumpsite, which covers an area of the Kenyan capital the size of 22 football pitches. On windy days, clouds of smoke engulf the nearby neighbourhoods. “You can’t breathe,” a woman who works in a nearby pharmacy tells The Fuller Project and VICE World News. It’s not just an issue at Dandora. Across Kenya’s dumpsites, a potentially toxic mix of everything from empty milk cartons to old tyres are being destroyed through open burning, according to a 2017 report by the government and the United Nations. Around the world, many of the estimated 20 million waste pickers in countries such as India, Ghana and Vietnam likely face similar health concerns. Estimates vary, but studies show this informal workforce is often mostly women.“This is a global problem,” says Griffins Ochieng, executive director for the Centre for Environmental Justice and Development (CEJAD), a Nairobi-based nonprofit focusing on the problem of plastic waste. “Any dumpsite – anywhere there is plastic pollution – women will be impacted.” This is because many materials that end up as waste contain toxic substances. Plastics and e-waste are known to contain and leach hazardous chemicals into the environment, including endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs), which have been linked to reduced fertility, pregnancy loss and irregular menstrual cycles, among many other conditions. Burning them releases or generates a number of highly toxic chemicals and heavy metals, with reported similar effects. The toxins are not only in the air but also in the soil and water, and for the many waste pickers who eat from the landfills, in their food, too.While men frequently take on more supervisory roles, women often spend the entire day rummaging, says Ochieng. “They’re in the thick of things… but the environment is a threat to their human health.”For years, acrid smoke has billowed across Dandora, often engulfing the surrounding neighbourhood on windy days.Globally, the amount of trash we produce – and where to put it – is a growing problem. Each year, the world generates 2.01 billion tonnes of household waste, the equivalent of more than 6,000 Empire State Buildings being collectively chucked out every 12 months. By 2050, the number is set to rise by more than 70 percent. In low-income countries, over 90 percent of waste is either dumped in the open or burned. It’s why waste pickers, like Wanjira, are often described as the backbone of waste and recycling industries. They’ve stepped in, an informal, often invisible workforce relied upon by governments in parts of Latin America and Asia and across Africa. Spending long days bent over, picking up and sorting waste discarded in streets and dumpsites, they recover more recyclable materials than formal waste management systems yet represent some of society’s most marginalised populations. In Kenya, roughly 3,000 to 5,000 waste pickers scatter across Dandora’s hills every day. Around the country, local organisations estimate the numbers reach nearly 50,000, although there is no official total.If Wanjira’s heavy, painful period had been a one-off, she might have been a little less worried. But she’s faced the same issue – often twice a month – for roughly 20 years, she says. When Wanjira was about 13 and her family could no longer afford school fees, she dropped out and started working with her mother, Jane, who was also a waste picker. Within several years, Wanjira’s problems with her menstruation started, she says. She’s not alone. In interviews with 32 women across Dandora and Gioto, another vast dumpsite in Nakuru, a three-hour drive from Nairobi, 21 women said their periods are irregular. Many, like Wanjira, face very heavy, painful periods once or twice a month. Others wait eight months for theirs. One in three say they have suffered serious issues when pregnant, including miscarriage, stillbirth and premature birth. About 10 to 15 percent of pregnancies worldwide end in miscarriage, according to March of Dimes, an organisation that works on pregnancy and postpartum health, while stillbirth and premature birth are much rarer.One 59-year-old woman who has worked at Dandora for nearly three decades is being treated for uterine cancer. “We hear these issues all the time,” says Joyce Wangari, a 23-year-old waste picker who has worked at Dandora since she was 12. She only gets her periods every two to three months. “It’s so common.”

Author Archives: David Evans

‘The smoke enters your body': A toxic trash site in Kenya is making women sick

This story is a collaboration between VICE World News and The Fuller Project.DANDORA, Kenya– As Winnie Wanjira rifles through mountains of waste at the Dandora dump in Nairobi, it’s not the discarded needles that most bother her. Nor the metal scraps that could shred her skin like paper. It’s not even the hot sun that beats down on the rancid rubbish, making the 36-year-old feel so dizzy she struggles to fill her sack with plastic bottles. Today, the mother of six is anxious about her period. It’s heavy, she says. So heavy she spent the last two days lying down in her windowless, single-bedroom home, unable to move. “The bleeding… is no joke,” she tells The Fuller Project and VICE World News. “I cannot come to work, I cannot go anywhere.” Joyce Wangari (left) and Winnie Wanjira are fighting to protect waste pickers’ rights. Now, on the third day, she’s back, hoping the jumper tied around her waist will cover any stains. “And it’s, like, black, not even the normal colour of periods,” she says. “That place… It kills. It really kills.”As far back as 2007, the United Nations Environment Program warned that Dandora posed a serious health threat to those working and living nearby. Yet while it is understood that exposure to the toxic chemicals found on dumpsites can result in cancer, respiratory problems and skin infections, scientists and environmental campaigners say relatively little attention has been paid to their impact on the reproductive health of waste pickers, who are often women. Materials such as plastic and e-waste contain a cocktail of chemicals that studies show can disturb the body’s hormone systems. As ever-higher volumes of trash continue to end up in landfills, informal workers like Wanjira will be on the front lines of what scientists are calling an emerging issue of global concern.Most waste pickers handle trash without gloves or masks and often live near or on the dumpsites, which intensifies their exposure to health risks.For years, acrid smoke has billowed across this sprawling dumpsite, which covers an area of the Kenyan capital the size of 22 football pitches. On windy days, clouds of smoke engulf the nearby neighbourhoods. “You can’t breathe,” a woman who works in a nearby pharmacy tells The Fuller Project and VICE World News. It’s not just an issue at Dandora. Across Kenya’s dumpsites, a potentially toxic mix of everything from empty milk cartons to old tyres are being destroyed through open burning, according to a 2017 report by the government and the United Nations. Around the world, many of the estimated 20 million waste pickers in countries such as India, Ghana and Vietnam likely face similar health concerns. Estimates vary, but studies show this informal workforce is often mostly women.“This is a global problem,” says Griffins Ochieng, executive director for the Centre for Environmental Justice and Development (CEJAD), a Nairobi-based nonprofit focusing on the problem of plastic waste. “Any dumpsite – anywhere there is plastic pollution – women will be impacted.” This is because many materials that end up as waste contain toxic substances. Plastics and e-waste are known to contain and leach hazardous chemicals into the environment, including endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs), which have been linked to reduced fertility, pregnancy loss and irregular menstrual cycles, among many other conditions. Burning them releases or generates a number of highly toxic chemicals and heavy metals, with reported similar effects. The toxins are not only in the air but also in the soil and water, and for the many waste pickers who eat from the landfills, in their food, too.While men frequently take on more supervisory roles, women often spend the entire day rummaging, says Ochieng. “They’re in the thick of things… but the environment is a threat to their human health.”For years, acrid smoke has billowed across Dandora, often engulfing the surrounding neighbourhood on windy days.Globally, the amount of trash we produce – and where to put it – is a growing problem. Each year, the world generates 2.01 billion tonnes of household waste, the equivalent of more than 6,000 Empire State Buildings being collectively chucked out every 12 months. By 2050, the number is set to rise by more than 70 percent. In low-income countries, over 90 percent of waste is either dumped in the open or burned. It’s why waste pickers, like Wanjira, are often described as the backbone of waste and recycling industries. They’ve stepped in, an informal, often invisible workforce relied upon by governments in parts of Latin America and Asia and across Africa. Spending long days bent over, picking up and sorting waste discarded in streets and dumpsites, they recover more recyclable materials than formal waste management systems yet represent some of society’s most marginalised populations. In Kenya, roughly 3,000 to 5,000 waste pickers scatter across Dandora’s hills every day. Around the country, local organisations estimate the numbers reach nearly 50,000, although there is no official total.If Wanjira’s heavy, painful period had been a one-off, she might have been a little less worried. But she’s faced the same issue – often twice a month – for roughly 20 years, she says. When Wanjira was about 13 and her family could no longer afford school fees, she dropped out and started working with her mother, Jane, who was also a waste picker. Within several years, Wanjira’s problems with her menstruation started, she says. She’s not alone. In interviews with 32 women across Dandora and Gioto, another vast dumpsite in Nakuru, a three-hour drive from Nairobi, 21 women said their periods are irregular. Many, like Wanjira, face very heavy, painful periods once or twice a month. Others wait eight months for theirs. One in three say they have suffered serious issues when pregnant, including miscarriage, stillbirth and premature birth. About 10 to 15 percent of pregnancies worldwide end in miscarriage, according to March of Dimes, an organisation that works on pregnancy and postpartum health, while stillbirth and premature birth are much rarer.One 59-year-old woman who has worked at Dandora for nearly three decades is being treated for uterine cancer. “We hear these issues all the time,” says Joyce Wangari, a 23-year-old waste picker who has worked at Dandora since she was 12. She only gets her periods every two to three months. “It’s so common.”

Plastic packaging might be biodegradable after all

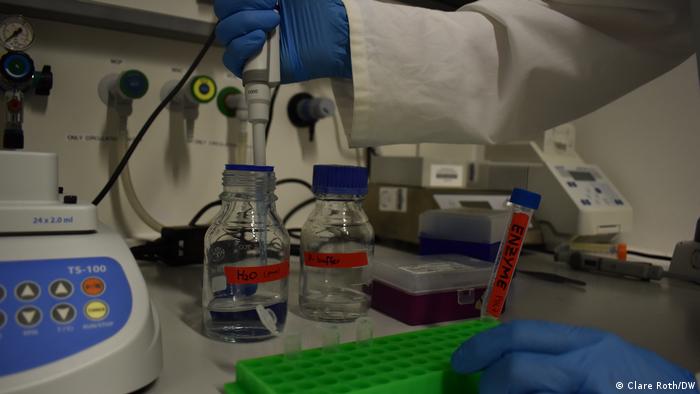

Leipzig researchers have found an enzyme that rapidly breaks down PET, the most widely produced plastic in the world. It might just eat your old tote bags.

While scavenging through a compost heap at a Leipzig cemetery, Christian Sonnendecker and his research team found seven enzymes they had never seen before. They were hunting for proteins that would eat PET plastic — the most highly produced plastic in the world. It is commonly used for bottled water and groceries like grapes. The scientists weren’t expecting much when they brought the samples back to the lab, said Sonnendecker when DW visited their Leipzig University laboratory. It was only the second dump they had rummaged through and they thought PET-eating enzymes were rare. But in one of the samples, they found an enzyme, or polyester hydrolase, called PHL7. And it shocked them. The PHL7 enzyme disintegrated an entire piece of plastic in less than a day. To test the rate at which the seven enzymes broke down PET, Sonnendecker and his team added a mixture of water, a phosphate buffer, which is often used to detect bacteria, for example, and the new enzyme to seven individual test tubes After adding the mixture to the test tubes, the team added tiny slivers of PET plastic to each container to see how quickly it took to degrade Two enzymes ‘eat’ plastic: PHL7 vs. LCC PHL7 appears to ‘eat’ PET plastic times faster than LCC, a standard enzyme used in PET plastic-eating experiments today. To ensure their discovery wasn’t a fluke, Sonnendecker’s team compared PHL7 to LCC, with both enzymes degrading multiple plastic containers. And they found it was true: PHL7 was faster. “I would have thought you’d need to sample from hundreds of different sites before you’d find one of these enzymes,” said Graham Howe, an enzymologist at Queens University in Ontario, Canada. Howe, who also studies PET degradation but was not involved in the Leipzig research, appeared to be amazed by the study published in Chemistry Europe. “Apparently, you go to nature and there are going to be enzymes that do this everywhere,” said Howe. PET plastic is everyone Although PET plastic can be recycled, it does not biodegrade. Like nuclear waste or a nasty comment to your partner, once PET plastic is created, it never really goes away. It can be refashioned into new products — it’s not hard to create a tote bag from recycled water bottles, for example. But the quality of the plastic weakens with each cycle. So, a lot of PET is eventually fashioned into products like carpets and — yes — an exorbitant number of tote bags that end up in landfill sites. There are two ways to look at solving this problem: The first is to stop production of all PET plastic. But the material is so common that even if companies stopped producing it immediately, there would still be millions of empty soft drink bottles — or tote bags fashioned from those bottles — lying around for thousands of years. This is what a grape container looks like after it’s been treated with the enzyme PHL7 — the white particles are leftover terephthalic acid and ethylene glycol, chemicals that can be used to create brand new PET rather than a lower quality version The second way is to force the plastic to degrade. Scientists have been trying to find enzymes that will do that for decades and in 2012 they found LCC, or “leaf-branch compost cutinase.” LCC was a major breakthrough because it showed that PETase, a component of LCC, can be used to degrade PET plastic when it is combined with another enzyme known as an esterase. Esterase enzymes are used to break chemical bonds in a process called hydrolysis. Scientists working on LCC have found that the enzyme does not differentiate between natural polymers and synthetic polymers — the latter being plastic. Instead, LCC recognizes PET plastic as a naturally occurring substance and eats it like it would a natural polymer. Engineering the enzyme Since the discovery of LCC, researchers like Sonnendecker have been looking for new PET-eating enzymes in nature. LCC is good, they say, but it has limitations. It is fast for what it is, but it still takes days to break down PET and the reactions have to occur at very high temperatures. Other scientists and researchers have been trying to figure out how to engineer LCC to make it more efficient. A French company called Carbios is doing that. They are engineering LCC to create a faster, more efficient enzyme. Elsewhere, researchers at the University of Texas in Austin have created a PET-eating protein using a machine learning algorithm. They say their protein can degrade PET plastic in 24 hours. David Zechel, a professor of chemistry at Queen’s University said these approaches always start with something that is known — the researchers don’t necessarily find anything new, but work to improve what has already been discovered. The team are testing a “pre-treatment” that is applied to soft drink bottles, like this one in the jar, before it’s degraded by the enzyme PHL7 This type of engineering is important as researchers try to create the optimal enzyme to degrade PET, said Zechel. Sonnendecker’s work shows that “we haven’t even remotely scratched the surface” in terms of the potential of naturally occurring enzymes “with respect to PET,” he said. Bottles still don’t biodegrade Sonnendecker’s newly discovered enzyme has its limitations, too. It can break down the containers you buy your grapes in at the grocery store, but it can’t break down a soft drink bottle. Not yet. The PET plastic used in drink bottles is stretched and chemically altered, making it tougher to biodegrade than the PET used in grape containers. In tests, Sonnendecker’s team has developed a pre-treatment that is applied to PET bottles, making it easier for the enzyme to degrade the plastic. But that research has yet to be published. With industry help, said the researcher, technology using PHL7 to break down PET at a large scale could be ready in around four years. Edited by: Zulfikar Abbany

New York state is looking for a new solution to plastic waste

Enlarge this image

A worker carries used drink bottles and cans for recycling at a collection point in Brooklyn, New York. Three decades of recycling have so far failed to reduce what we throw away, especially plastics.

Ed Jones/AFP via Getty Images

Ed Jones/AFP via Getty Images

After recycling’s failure to appreciably reduce the amount of plastic the U.S. throws away, some states are taking a new approach, transferring the onus of recycling from consumers to product manufacturers. In the past 12 months, legislatures in Maine, Oregon and Colorado have passed “extended producer responsibility” laws on packaging. The legislation essentially forces producers of consumer goods — such as beverage-makers, shampoo companies and food corporations — to pay for the disposal of the packages and containers their products come in. The process is intended to nudge manufacturers to use more easily recyclable materials, compostable packaging or less packaging. Now, the New York legislature is deliberating two extended producer responsibility bills as its session nears its June 2 close. Lobbying by business and environmental groups has been particularly intense around details such as what recycling goals must be met and who sets them. Industry and environmentalists alike believe that when a state as big as New York adopts a law, it creates a template or standard that other states might adopt too.

“I’m exhausted,” said Judith Enck, founder and president of the advocacy group Beyond Plastics, who has been lobbying legislators on the issue. “If you have a state the size of New York get it wrong on extended producer responsibility, it would have a ripple effect on other states.” What would this approach look like? Extended producer responsibility — the ungainly name comes from a 1990 paper by Swedish academics Thomas Lindhqvist and Karl Lidgren — took root in Europe 30 years ago. Many U.S. states have such policies for e-waste and mattresses. But their adoption for packaging is fairly recent in the U.S., and those programs won’t be fully up and running for years. While each state’s legislation varies, the system generally works like this: Beverage companies, shampoo-makers, food manufacturers and other producers will keep track of how much of each sort of packaging they use. These producers will reimburse government recycling programs for handling the waste, either directly or through a consortium called a “producer responsibility organization.” Fees will be lower for companies that use easily recyclable, compostable or even reusable packaging, a mechanism that supporters say will provide incentives to adopt more sustainable practices. Recycling centers will use the money to cover their operating costs, expand outreach and education, and invest in new equipment.

“We think corporations will produce less virgin materials because they are charged by the amount they put out there, and certainly less eco-unfriendly materials,” said New York state Sen. Todd Kaminsky, a Democrat from Long Island who sponsored one of the bills pending in Albany.

NSW plastic bag ban: how will it work and what will be gained from it?

NSW plastic bag ban: how will it work and what will be gained from it? Lightweight plastic bags will be banned from Wednesday, with distributors being the initial targets Get our free news app; get our morning email briefing Single-use plastic bags will be banned in New South Wales this week. The decision follows similar …

Continue reading “NSW plastic bag ban: how will it work and what will be gained from it?”

Australian study finds microplastics in world's most remote oceans

An Australian man who has circumnavigated the world 11 times in a yacht has used his most recent voyage to collect seawater samples, which scientists now say are proof that microplastics have polluted even the world’s most remote oceans.Key points:Researchers used 177 samples collected by lone sailor Jon Sanders on his 11th circumnavigation voyageThe scientists say microplastics were detected in places that had never been tested, including remote parts of the oceanCurtin University says previous studies had not tested for microplastics in southern oceansResearchers from Curtin University used samples collected by lone sailor Jon Sanders to develop what they described as the first accurate measure of the presence of microplastics in far-flung ocean environments.”The aim of the study was to target areas of the world’s oceans not previously sampled for microplastics and to produce a complete global snapshot of microplastic distribution,” Professor Kliti Grice, the lead researcher on the study, said.”Our analysis found microplastics were present in the vast majority of the waters sampled by Jon, even in very remote ocean areas of the Southern Hemisphere.”Mr Sanders collected hundreds of samples during his expedition, which he completed in January last year, spanning 46,100 kilometres of ocean, including areas that have never been tested for microplastics before.Project initiated by sailor

George Monbiot: Microplastics in sewage: a toxic combination that is poisoning our land

Microplastics in sewage: a toxic combination that is poisoning our landGeorge MonbiotPolicy failure and lack of enforcement have left Britain’s waterways and farmland vulnerable to ‘forever chemicals’ We have recently woken up to a disgusting issue. Rather than investing properly in new sewage treatment works, water companies in the UK – since they were privatised in 1989 – have handed £72 bn in dividends to their shareholders. Our sewerage system is antiquated and undersized, and routinely bypassed altogether, as companies allow raw human excrement to pour directly into our rivers. They have reduced some of them to stinking, almost lifeless drains.This is what you get from years of policy failure and the near-collapse of monitoring and enforcement by successive governments. Untreated sewage not only loads our rivers with excessive nutrients, but it’s also the major source of the microplastics that now pollute them. It contains a wide range of other toxins, including PFASs: the “forever chemicals” that were the subject of the movie Dark Waters. This may explain the recent apparent decline in otter populations: after recovering from the organochlorine pesticides used in the 20th century, they are now being hit by new pollutants.Microplastics found deep in lungs of living people for first timeRead moreBut here’s a question scarcely anyone is asking: what happens when our sewerage system works as intended? What happens when the filth is filtered out and the water flowing out of sewage treatment plants is no longer hazardous to life? I stumbled across the answer while researching my book, Regenesis, and I’m still reeling from it. When the system works as it is meant to, it is likely to be just as harmful as it is when bypassed by unscrupulous water companies. It’s an astonishing and shocking story, but it has hardly been touched by the media.We are often told that the microplastics entering the sewage system, which come from tyre crumb washing off the roads, the synthetic clothes we wear and many other sources, are a wicked problem, almost impossible to solve. But a modern, well-run sewage treatment works removes 99% of these fibres from wastewater. So far, so good. But – and at this point you may wish to decide whether to laugh or cry – having screened them out of the water supply, the treatment companies then release them back into the wild. In the UK, of the sewage sludge screened out by treatment works, 87% is sent to farms. The microplastics so carefully removed from wastewater by the treatment process are then spread across the land in the sewage sludge the water companies sell to farmers as fertiliser.Then what happens to them? Some – perhaps most – wash off the soil and into the rivers: in other words, whether sewage is screened or not, the microplastics it contains end up in the same place. Others accumulate in the soil.It’s hard to decide which is worse. Experiments show how microplastics cascade through soil food webs, poisoning some of the animals that inhabit it. When they decompose into nanoparticles, they can be absorbed by soil fungi and accumulated by plants. We currently have no idea what the consequences of eating these contaminated crops might be.The testing of sewage sludge has not been updated since 1989, so there is no checking for plastic particles or most other synthetic chemicals. A study commissioned but then kept secret by the government found that the sewage sludge being spread on our farmland contains a remarkable cocktail of dangerous substances, including PFASs, benzo(a)pyrene (a group 1 carcinogen), dioxins, furans, PCBs and PAHs, all of which are persistent and potentially cumulative.Where did they come from? Because our waste streams are not separated and poorly regulated, anywhere and everywhere. The major source of PFASs in sewage is probably the building trade. “Forever chemicals” are found in paints, sealants and coatings, caulks, adhesives and roofing materials. Evidence sent to me by an industry insider suggests that regulators the world over turn a blind eye to liquid waste disposal on construction sites. Tools are washed and surfaces sprayed with water that’s then poured down the drain. Without regulation, contractors have no incentive to use technologies that ensure liquid waste is contained. Why go to this expense if your competitors don’t have to?Raw sewage ‘pumped into English bathing waters 25,000 times in 2021’Read moreCould this story get any worse? Oh yes. Microplastics are sometimes spread deliberately on the soil by farmers, to make it more friable. Across Europe, thousands of tonnes of plastic are also added to fertilisers, to prevent them from caking; or to delay the release of the nutrients they contain. Fertiliser pellets are coated with plastic films – polyurethane, polystyrene, PVC, polyacrylamide and other synthetic polymers– some of which are known to be toxic and all of which disintegrate into microplastics. It is almost unbelievable that the deliberate contamination of agricultural soils with persistent and cumulative pollutants is both widespread and legal.This practice, as well as the spreading of contaminated sewage sludge, urgently needs to be stopped, before large tracts of farmland become unusable, and the damage to ecosystems, from soil to sea, irreversible. It’s tragic that the nutrients in sewage sludge can’t safely be used, but it seems to me that there’s no immediate solution, in our dysfunctional system, but to incinerate it. Only when toxic, accumulating chemicals are banned, waste streams separated and proper tests conducted will sewage be safe to spread.Right now we are poisoning the land and, in all likelihood, poisoning ourselves. It could turn out to be one of the most deadly issues of all. And hardly anyone knows.

George Monbiot will discuss his book Regenesis at a Guardian Live event on Monday 30 May. Book tickets in-person or online here

George Monbiot is a Guardian columnist

TopicsEnvironmentOpinionWaterPollutionWasteAgriculturecommentReuse this content

Millions of Amazon mailers at heart of anti-plastic vote today

Amazon is facing vote from its shareholders and environmentalists this week over its use of plastic packaging.

Seattleites may have caught wind of the campaign around Amazon already, through billboards and yard signs featuring turtles caught in plastic. The message: stop using its flimsy plastic packaging that too easily ends up in marine ecosystems.Amazon began its annual investors meeting at 9 a.m. Wednesday. It was expected to advise shareholders to vote “no” on a resolution that would require the corporation to cut down plastic pollution. The resolution would require the company to take two steps it never has before on plastics. Those are: disclose how much plastic packaging it uses, and strategize how to move away from the thin, landfill bound packaging it uses now. The backers say there is hope for this to pass.

“In India, legislation was passed that required Amazon to move away from plastic packaging, and they’ve since done so,” says Sara Holzknecht with the group Oceana.Oceana has researched Amazon’s use of plastic packaging worldwide and is backing this resolution. They also helped run the public campaign that had Seattle homeowners placing yard signs with a plea to Amazon.Holzknecht says Amazon is one of the largest corporate users of flimsy plastics, which are hard (if not impossible) to recycle curbside. She says its partly a business case for the corporation. “Amazon, with its resources, is certainly an industry leader in a lot of ways and could be innovating away from plastics and away from paper mailers.” Again, she says, it has already made innovations in India when it was legally bound to.A report from Oceana estimates that up to 22 million pounds of Amazon’s plastic packaging ended up in marine ecosystems in 2019. Another way of putting it, says Holzknecht, is that in 2020 alone “the company used enough plastic to encircle our globe nearly 600 times in the form of plastic air pillows.”

Amazon executives argue the company is already committed to addressing plastic pollution. But, Amazon is lobbying shareholders to vote no.Amazon executives say, in a letter to investors, they share the concerns outlined in the resolution and are engaged in efforts to develop recycling infrastructure. In addition, the company says it plans to replace its mailing envelopes with a recyclable padded mailer by the end of this year in the U.S.The resolution, if passed, would require the company to strategize how it could reduce plastic use by at least one-third.

Millions of Amazon mailers at heart of anti-plastic vote today

Amazon is facing vote from its shareholders and environmentalists this week over its use of plastic packaging.

Seattleites may have caught wind of the campaign around Amazon already, through billboards and yard signs featuring turtles caught in plastic. The message: stop using its flimsy plastic packaging that too easily ends up in marine ecosystems.Amazon began its annual investors meeting at 9 a.m. Wednesday. It was expected to advise shareholders to vote “no” on a resolution that would require the corporation to cut down plastic pollution. The resolution would require the company to take two steps it never has before on plastics. Those are: disclose how much plastic packaging it uses, and strategize how to move away from the thin, landfill bound packaging it uses now. The backers say there is hope for this to pass.

“In India, legislation was passed that required Amazon to move away from plastic packaging, and they’ve since done so,” says Sara Holzknecht with the group Oceana.Oceana has researched Amazon’s use of plastic packaging worldwide and is backing this resolution. They also helped run the public campaign that had Seattle homeowners placing yard signs with a plea to Amazon.Holzknecht says Amazon is one of the largest corporate users of flimsy plastics, which are hard (if not impossible) to recycle curbside. She says its partly a business case for the corporation. “Amazon, with its resources, is certainly an industry leader in a lot of ways and could be innovating away from plastics and away from paper mailers.” Again, she says, it has already made innovations in India when it was legally bound to.A report from Oceana estimates that up to 22 million pounds of Amazon’s plastic packaging ended up in marine ecosystems in 2019. Another way of putting it, says Holzknecht, is that in 2020 alone “the company used enough plastic to encircle our globe nearly 600 times in the form of plastic air pillows.”

Amazon executives argue the company is already committed to addressing plastic pollution. But, Amazon is lobbying shareholders to vote no.Amazon executives say, in a letter to investors, they share the concerns outlined in the resolution and are engaged in efforts to develop recycling infrastructure. In addition, the company says it plans to replace its mailing envelopes with a recyclable padded mailer by the end of this year in the U.S.The resolution, if passed, would require the company to strategize how it could reduce plastic use by at least one-third.

Some elephants are getting too much plastic in their diets

In India, the large mammals see trash in village dumps as a buffet, but researchers found they are inadvertently consuming packaging and utensils.Some Asian elephants are a little shy about their eating habits. They sneak into dumps near human settlements at the edges of their forest habitats and quickly gobble up garbage — plastic utensils, packaging and all. But their guilty pleasure for fast food is traveling with them — elephants are transporting plastic and other human garbage deep into forests in parts of India.“When they defecate, the plastic comes out of the dung and gets deposited in the forest,” said Gitanjali Katlam, an ecological researcher in India.While a lot of research has been conducted on the spread of plastics from human pollution into the world’s oceans and seas, considerably less is known about how such waste moves with wildlife on land. But elephants are important seed dispersers, and research published this month in the Journal for Nature Conservation shows that the same process that keeps ecosystems functioning might carry human-made pollutants into national parks and other wild areas. This plastic could have negative effects on the health of elephants and other species that have consumed the material once it has passed through the large mammals’ digestive systems.Dr. Katlam first noticed elephants feeding on garbage on trail cameras during her Ph.D. work at Jawaharlal Nehru University. She was studying which animals visited garbage dumps at the edge of villages in northern India. At the time, she and her colleagues also noticed plastic in the elephants’ dung. With the Nature Science Initiative, a nonprofit focused on ecological research in northern India, Dr. Katlam and her colleagues collected elephant dung in Uttarakhand state.The researchers found plastic in all of the dung near village dumps and in the forest near the town of Kotdwar. They walked only a mile or two into the forest in their search for dung, but the elephants probably carried the plastic much farther, Dr. Katlam said. Asian elephants take about 50 hours to pass food and can walk six miles to 12 miles in a day. In the case of Kotdwar, this is concerning because the town is only a few miles from a national park.“This adds evidence to the fact that plastic pollution is ubiquitous,” said Agustina Malizia, an independent researcher with the National Scientific and Technical Research Council of Argentina who was not involved in this research but studied the effects of plastic on land ecosystems. She says the study is “extremely necessary,” as it might be one of the first reports of a very large land animal ingesting plastic.Plastic comprised 85 percent of the waste found in the elephant dung from Kotdwar. The bulk of this came from food containers and cutlery, followed by plastic bags and packaging. But the researchers also found glass, rubber, fabric and other waste. Dr. Katlam said the elephants were likely to have been seeking out containers and plastic bags because they still had leftover food inside. The utensils probably were eaten in the process.While trash passes through their digestive systems, the elephants may be ingesting chemicals like polystyrene, polyethylene, bisphenol A and phthalates. It is uncertain what damage these substances can cause, but Dr. Katlam worries that they may contribute to declines in elephant population numbers and survival rates.“It is known from other animals that their stomachs may get filled with plastics, causing mechanical damage,” said Carolina Monmany Garzia, who works with Dr. Malizia in Argentina and was not involved in Dr. Katlam’s study.Other animals may consume the plastic again once it is transported into the forest through the elephants’ dung. “It has a cascading effect,” Dr. Katlam said.Dr. Katlam said that governments in India should take steps to manage their solid waste to avoid these kinds of issues. But individuals can help, too, by separating their food waste from the containers so that plastic does not end up getting eaten so much by accident.“This is a very simple step, but a very important step,” she said.“We need to realize and understand how the overuse of plastics is affecting the environment and the organisms that inhabit them,” Dr. Mealizia said.