The shoes from Blueview, a startup helmed by a molecular biology professor, use an algae-based polyurethane foam that can biodegrade in compost, soil, and even the ocean.

[Photo: courtesy Blueview]

By

Author Archives: David Evans

Blueview sneakers are fully biodegradable, including the soles

The shoes from Blueview, a startup helmed by a molecular biology professor, use an algae-based polyurethane foam that can biodegrade in compost, soil, and even the ocean.

[Photo: courtesy Blueview]

By

Pick up the pieces: the battle to clean up Cornwall’s beaches

Pick up the pieces: the battle to clean up Cornwall’s beaches Plastic pollution blights the Cornish coast, but local people are tackling the problemWhen eight-year-old Harriet Orme saw a dead hawksbill turtle in her Cornwall village’s harbour three years ago, the image haunted her. Not because the huge, critically endangered turtle had crossed the seas from the tropics to a defunct fishing harbour on the north coast of Cornwall, but because it had most probably died after ingesting thousands of tiny pieces of plastic.“Harriet is a womble,” her mother, Sophie Orme, says. “Now, wherever she goes, she automatically picks up litter and hands it to me.” The two are spending their morning, like countless mornings before, litter-picking on their nearest beach. In their home town of Portreath, with a population of around 1,400 permanent residents, environmental custodianship is catching on. “It’s becoming the culture of the whole village. From the village elders right down to the youngest kids. Even the local pub runs nightly beach cleans in the summer,” Orme says. The area’s social values, she believes, are changing, much like when smoking became taboo. “You become a pariah if you litter,” she says.Across Cornwall, community beach cleans have gathered momentum as a year-round activity appealing to all ages. Unlike surfing, dog-walking or cold-water swimming, beach cleans require little equipment or hardiness – just a common goal to keep treasured outdoor spaces litter-free.“Litter was always a part of my childhood in north Cornwall,” says 24-year-old Emily Stevenson. “We would build sandcastles out of plastic.” Although she and her father, Rob Stevenson, often carried out impromptu beach cleans, it was not until 2017 that they held their first community clean. But after a serendipitous moment made headlines – when Emily unearthed an empty packet of crisps from 1997, the same year she was born, it led to her wearing a graduation dress made from crisp packets that was widely reported – numbers of volunteers “exploded”. The duo formed the social enterprise Beach Guardian, and have since spent thousands of hours scouring various cliffs and coves in more than 200 beach cleans.Beach Guardian focuses its efforts on the seven bays between Newquay and Padstow, two of the county’s most well-trodden holiday destinations. This stretch of coastline is Rick Stein territory – the whimsical Cornwall of foraging in hedgerows, steaming mussels and stargazy pie – or at least as television would have you believe. But in the dead of winter, when country lanes are quiet and the long swathes of sand are no longer cluttered by windbreakers, beach towels and body boards, bands of locals come to the beach on the hunt for rubbish.On a winter morning around 50 people, armed with litter pickers and recycling sacks, have come out on a Sunday to offer a hand. Stormy weather and high spring tides have made rich pickings for them, as buried plastics, hidden for decades at the bottom of the sea bed, have churned up to the surface. Most volunteers crouch over tangles of seaweed, fishing plastic from burrows, but a small group leaves to remove a plastic pontoon wedged into a cliff before it breaks up into minuscule pieces of polystyrene.Around 5,000 items of marine plastic pollution exist for each mile of beach in the UK, according to the Marine Conservation Society. And, living in the county with the largest coastline (422 miles), it is no surprise that the Cornish are deeply invested in their surroundings. Fishermen’s kisses, nurdles and biobeads – special names for fragments of fishing nets and small plastic pellets – are part of the vernacular, recognised by locals as devastating to marine life. It can be an uphill battle when you realise the “unquantifiable” amount of microplastics in the ocean, Stevenson acknowledges. This doesn’t deter the most dedicated volunteers, who pass kitchen sieves over the sand, scouting for plastic flecks of colour.On the beach, a mother holds open a bag for her child, who runs back and forth, gleefully adding “juicy bits of plastic” to a bulging pile. “Once you start seeing it, you can’t not see it again,” Zoe Collis says. “By coming here you see the scale and complexity of the problem. It means when you go home you then start thinking, right, what do I not need? Do I need that plastic bottle of water? Probably not.”Beach cleans became a vital way for her family to integrate after they relocated from Staffordshire to Cornwall six years ago. “You start seeing the same faces. And you find out other things going on. It’s been a great way of finding a group of buddies and building a community,” she says. During the long days of the pandemic, regular cleans were a lifeline for families like hers. Especially at Christmas, as Omicron torpedoed festive plans, beach cleans provided a welcome escape. “We had hot chocolate and mince pies afterwards. It was something to do to get out of the house that felt safe,” Collis adds.After spending his childhood summers in north Cornwall and working on a nearby campsite as a student, Mark Pendlebury retired to the county late last year. At his first beach clean, he wants to give back to the beaches he has spent over five decades enjoying. Opening his palm, Pendlebury reveals four pieces of Lego, salvaged from a cargo spill. In 1997 more than 4.8m pieces of Lego bound for New York were lost at sea and are still washing up on Cornish beaches today. Among the pieces Pendlebury finds are a canary-yellow surfboard and a teal, thumb-sized figurine, which vaguely resembles an elephant, or perhaps a hippo. It’s tricky to tell as the bricks are slightly misshapen, their trademark bumps licked by waves until rounded. Such items are considered collectibles by avid beachcombers: the rare bits of junk that find their way to the shores from exotic places or decades past.“I have folders and folders of stuff that I refuse to give up,” says Emily Stevenson. “Each one tells you a story of a particular beach clean.” Her big thing is crisp packets. “I’ll remember this clean in 10 years’ time by this packet. Memories just seem to cling on to it.”Of course, front rooms and garden sheds can’t hold everything the cleaners find. Instead, Beach Guardian’s plastic bounty is used for educational purposes – as art activism. A statement from the group says: “Everything from our beach cleans is brought up to our Beach Guardian Lab. Volunteers sort through what we have. The large items like nets and rope are used for large art installations like our whale, giant puppets and our Plastic Age stone circle. The smaller items are used for school resources so that pupils can see first-hand what we are finding on our beach cleans and watch our Tune In Tuesday videos on YouTube.”Nets, ropes and large plastic items are shredded down and turned into kayaks to help recover more items at remote coves while other plastics are recycled into beach-cleaning stations. As a last resort, all waste in Cornwall is incinerated to generate electricity, so it’s very unlikely that anything will end up back in the ocean, the environment or in landfill.Beach Guardian is also pushing for policy change, starting with local authorities and businesses, through to politicians and multinational corporations. The team has met decision-makers from parliament and PepsiCo, to present the dangers of plastic in our ecosystem. Stevenson uses an analogy: “If you have a leaky sink in your bathroom, you wouldn’t spend year after year mopping up the floor; you’d fix the tap. Beach cleaning is mopping up the floor, but we’ll do that forever unless we turn off the plastic tap.”However, when the tourist season strikes, Cornwall tackles a very different litter crisis. Kevin Wood, who works in maintenance in Watergate Bay, is tasked with cleaning the beach every morning, mopping up the residue of picnics, barbecues and late-night beach parties.“It’s horrendous in the summer. We literally fill up black bags with barbecue rubbish, crisp packets, plastic spades, all sorts. When the bins are full, people just throw rubbish on the floor,” he says. According to Wood, fires cause some of the worst damage. Last year was particularly dire, with wooden chairs and tables stolen from the forecourt of a hotel used as fuel in the name of a good time. “I wish they could see it now when we’re picking mainly old stuff and fishing gear, so they could see the difference in the summer,” he says.One solution has been the rollout of individual beach-cleaning stations. The concept is amazingly simple – place a board, a litter picker and a bag at the entry point to each beach. In bright blue and yellow, the stations are hard to miss, serving as a constant reminder of environmental responsibility. The scheme, run by Cornish charity The 2 Minute Foundation, piloted in 2014 and now there are over 1,000 stations, one in every continent of the world.“The stations don’t discriminate. Lots of tourists will come along and take part, especially those who aren’t clued in about the organised beach cleans,” says Martin Dorey, the charity’s founder. He collaborates with tour operators that run summer beach cleans for holidaymakers, as well as artists selling jewellery and trinkets made from marine debris. “It appeals to people’s sense of giving back and feeling like they belong to the community by doing something positive,” Dorey says.Beach cleaners are encouraged to share photos under the hashtag 2minutebeachclean. After the first station was installed in Bude, Cornwall, Dorey measured a 68% drop in litter left on the beach that year. Fifteen years later, with hashtags registered as far as Antarctica, the scale of the charity’s work is harder to track. “It’s the key that unlocks laziness. Two minutes is nothing; everybody’s got two minutes,” says Dorey. By setting an achievable goal people are inspired to make incremental changes. “We don’t need 100 perfect people – we need everybody to be imperfect, but at least trying,” he adds.For Dorey, beach cleaning offered respite after a difficult divorce. But he has also heard testimonies from others who have used the ritual to silence anxious or even suicidal thoughts. Now, The 2 Minute Foundation has an employee trained as a mental-health first aider, in the hope of spotting signs of struggle early on.The benefits of beach cleaning on mental health are still relatively anecdotal, although recognition of nature’s restorative qualities is becoming more mainstream. In lockdown, savouring time spent in open spaces became a crutch for many of us, to such an extent that in July 2020, the Environment Secretary dedicated £4m to “green social prescribing”. GPs and other healthcare practitioners can refer patients with mental health concerns to nature-based activities, such as local walking schemes and community gardening projects.This opens the door to exploring our relationship to aquatic environments, ponds, lakes, rivers and oceans. At the forefront is BlueHealth, a pan-European research project led by a University of Exeter department based in Truro. In a 2019 study, experts found that people living less than 1km from the UK coast had “significantly lower” odds of being at a high risk of “common mental disorders”, such as anxiety or depression, compared to those living further than 50km away. The link was stronger within socioeconomically deprived communities, indicating that access to blue spaces could reduce health inequalities.“The doctors of yesteryear had the right idea when they would prescribe the coastline as a type of medicine,” says Jolyon Sharpe, a countryside officer at Cornwall Council. “Beach cleaning can be done beautifully in isolation; it can be very therapeutic, almost meditative,” says Sharpe. The melange of sounds – crashing waves, blustering wind and seagulls crooning – is pivotal. “Everything you hear is a sensory overload, and that’s incredibly good for your mental wellbeing.” And, when you add an altruistic element, such as cleaning, the satisfaction is twofold.“One thing that brings everyone together is that the coastline of Cornwall is beautiful,” says Sharpe. “The key thing is the beach is for everyone to enjoy, but we’ve got to protect it. Litter picking is one really simple way that everybody can give back to the environment that they love.”TopicsPollutionThe ObserverPlasticsCornwallCornwall holidaysfeaturesReuse this content

Pick up the pieces: the battle to clean up Cornwall’s beaches

Pick up the pieces: the battle to clean up Cornwall’s beaches Plastic pollution blights the Cornish coast, but local people are tackling the problemWhen eight-year-old Harriet Orme saw a dead hawksbill turtle in her Cornwall village’s harbour three years ago, the image haunted her. Not because the huge, critically endangered turtle had crossed the seas from the tropics to a defunct fishing harbour on the north coast of Cornwall, but because it had most probably died after ingesting thousands of tiny pieces of plastic.“Harriet is a womble,” her mother, Sophie Orme, says. “Now, wherever she goes, she automatically picks up litter and hands it to me.” The two are spending their morning, like countless mornings before, litter-picking on their nearest beach. In their home town of Portreath, with a population of around 1,400 permanent residents, environmental custodianship is catching on. “It’s becoming the culture of the whole village. From the village elders right down to the youngest kids. Even the local pub runs nightly beach cleans in the summer,” Orme says. The area’s social values, she believes, are changing, much like when smoking became taboo. “You become a pariah if you litter,” she says.Across Cornwall, community beach cleans have gathered momentum as a year-round activity appealing to all ages. Unlike surfing, dog-walking or cold-water swimming, beach cleans require little equipment or hardiness – just a common goal to keep treasured outdoor spaces litter-free.“Litter was always a part of my childhood in north Cornwall,” says 24-year-old Emily Stevenson. “We would build sandcastles out of plastic.” Although she and her father, Rob Stevenson, often carried out impromptu beach cleans, it was not until 2017 that they held their first community clean. But after a serendipitous moment made headlines – when Emily unearthed an empty packet of crisps from 1997, the same year she was born, it led to her wearing a graduation dress made from crisp packets that was widely reported – numbers of volunteers “exploded”. The duo formed the social enterprise Beach Guardian, and have since spent thousands of hours scouring various cliffs and coves in more than 200 beach cleans.Beach Guardian focuses its efforts on the seven bays between Newquay and Padstow, two of the county’s most well-trodden holiday destinations. This stretch of coastline is Rick Stein territory – the whimsical Cornwall of foraging in hedgerows, steaming mussels and stargazy pie – or at least as television would have you believe. But in the dead of winter, when country lanes are quiet and the long swathes of sand are no longer cluttered by windbreakers, beach towels and body boards, bands of locals come to the beach on the hunt for rubbish.On a winter morning around 50 people, armed with litter pickers and recycling sacks, have come out on a Sunday to offer a hand. Stormy weather and high spring tides have made rich pickings for them, as buried plastics, hidden for decades at the bottom of the sea bed, have churned up to the surface. Most volunteers crouch over tangles of seaweed, fishing plastic from burrows, but a small group leaves to remove a plastic pontoon wedged into a cliff before it breaks up into minuscule pieces of polystyrene.Around 5,000 items of marine plastic pollution exist for each mile of beach in the UK, according to the Marine Conservation Society. And, living in the county with the largest coastline (422 miles), it is no surprise that the Cornish are deeply invested in their surroundings. Fishermen’s kisses, nurdles and biobeads – special names for fragments of fishing nets and small plastic pellets – are part of the vernacular, recognised by locals as devastating to marine life. It can be an uphill battle when you realise the “unquantifiable” amount of microplastics in the ocean, Stevenson acknowledges. This doesn’t deter the most dedicated volunteers, who pass kitchen sieves over the sand, scouting for plastic flecks of colour.On the beach, a mother holds open a bag for her child, who runs back and forth, gleefully adding “juicy bits of plastic” to a bulging pile. “Once you start seeing it, you can’t not see it again,” Zoe Collis says. “By coming here you see the scale and complexity of the problem. It means when you go home you then start thinking, right, what do I not need? Do I need that plastic bottle of water? Probably not.”Beach cleans became a vital way for her family to integrate after they relocated from Staffordshire to Cornwall six years ago. “You start seeing the same faces. And you find out other things going on. It’s been a great way of finding a group of buddies and building a community,” she says. During the long days of the pandemic, regular cleans were a lifeline for families like hers. Especially at Christmas, as Omicron torpedoed festive plans, beach cleans provided a welcome escape. “We had hot chocolate and mince pies afterwards. It was something to do to get out of the house that felt safe,” Collis adds.After spending his childhood summers in north Cornwall and working on a nearby campsite as a student, Mark Pendlebury retired to the county late last year. At his first beach clean, he wants to give back to the beaches he has spent over five decades enjoying. Opening his palm, Pendlebury reveals four pieces of Lego, salvaged from a cargo spill. In 1997 more than 4.8m pieces of Lego bound for New York were lost at sea and are still washing up on Cornish beaches today. Among the pieces Pendlebury finds are a canary-yellow surfboard and a teal, thumb-sized figurine, which vaguely resembles an elephant, or perhaps a hippo. It’s tricky to tell as the bricks are slightly misshapen, their trademark bumps licked by waves until rounded. Such items are considered collectibles by avid beachcombers: the rare bits of junk that find their way to the shores from exotic places or decades past.“I have folders and folders of stuff that I refuse to give up,” says Emily Stevenson. “Each one tells you a story of a particular beach clean.” Her big thing is crisp packets. “I’ll remember this clean in 10 years’ time by this packet. Memories just seem to cling on to it.”Of course, front rooms and garden sheds can’t hold everything the cleaners find. Instead, Beach Guardian’s plastic bounty is used for educational purposes – as art activism. A statement from the group says: “Everything from our beach cleans is brought up to our Beach Guardian Lab. Volunteers sort through what we have. The large items like nets and rope are used for large art installations like our whale, giant puppets and our Plastic Age stone circle. The smaller items are used for school resources so that pupils can see first-hand what we are finding on our beach cleans and watch our Tune In Tuesday videos on YouTube.”Nets, ropes and large plastic items are shredded down and turned into kayaks to help recover more items at remote coves while other plastics are recycled into beach-cleaning stations. As a last resort, all waste in Cornwall is incinerated to generate electricity, so it’s very unlikely that anything will end up back in the ocean, the environment or in landfill.Beach Guardian is also pushing for policy change, starting with local authorities and businesses, through to politicians and multinational corporations. The team has met decision-makers from parliament and PepsiCo, to present the dangers of plastic in our ecosystem. Stevenson uses an analogy: “If you have a leaky sink in your bathroom, you wouldn’t spend year after year mopping up the floor; you’d fix the tap. Beach cleaning is mopping up the floor, but we’ll do that forever unless we turn off the plastic tap.”However, when the tourist season strikes, Cornwall tackles a very different litter crisis. Kevin Wood, who works in maintenance in Watergate Bay, is tasked with cleaning the beach every morning, mopping up the residue of picnics, barbecues and late-night beach parties.“It’s horrendous in the summer. We literally fill up black bags with barbecue rubbish, crisp packets, plastic spades, all sorts. When the bins are full, people just throw rubbish on the floor,” he says. According to Wood, fires cause some of the worst damage. Last year was particularly dire, with wooden chairs and tables stolen from the forecourt of a hotel used as fuel in the name of a good time. “I wish they could see it now when we’re picking mainly old stuff and fishing gear, so they could see the difference in the summer,” he says.One solution has been the rollout of individual beach-cleaning stations. The concept is amazingly simple – place a board, a litter picker and a bag at the entry point to each beach. In bright blue and yellow, the stations are hard to miss, serving as a constant reminder of environmental responsibility. The scheme, run by Cornish charity The 2 Minute Foundation, piloted in 2014 and now there are over 1,000 stations, one in every continent of the world.“The stations don’t discriminate. Lots of tourists will come along and take part, especially those who aren’t clued in about the organised beach cleans,” says Martin Dorey, the charity’s founder. He collaborates with tour operators that run summer beach cleans for holidaymakers, as well as artists selling jewellery and trinkets made from marine debris. “It appeals to people’s sense of giving back and feeling like they belong to the community by doing something positive,” Dorey says.Beach cleaners are encouraged to share photos under the hashtag 2minutebeachclean. After the first station was installed in Bude, Cornwall, Dorey measured a 68% drop in litter left on the beach that year. Fifteen years later, with hashtags registered as far as Antarctica, the scale of the charity’s work is harder to track. “It’s the key that unlocks laziness. Two minutes is nothing; everybody’s got two minutes,” says Dorey. By setting an achievable goal people are inspired to make incremental changes. “We don’t need 100 perfect people – we need everybody to be imperfect, but at least trying,” he adds.For Dorey, beach cleaning offered respite after a difficult divorce. But he has also heard testimonies from others who have used the ritual to silence anxious or even suicidal thoughts. Now, The 2 Minute Foundation has an employee trained as a mental-health first aider, in the hope of spotting signs of struggle early on.The benefits of beach cleaning on mental health are still relatively anecdotal, although recognition of nature’s restorative qualities is becoming more mainstream. In lockdown, savouring time spent in open spaces became a crutch for many of us, to such an extent that in July 2020, the Environment Secretary dedicated £4m to “green social prescribing”. GPs and other healthcare practitioners can refer patients with mental health concerns to nature-based activities, such as local walking schemes and community gardening projects.This opens the door to exploring our relationship to aquatic environments, ponds, lakes, rivers and oceans. At the forefront is BlueHealth, a pan-European research project led by a University of Exeter department based in Truro. In a 2019 study, experts found that people living less than 1km from the UK coast had “significantly lower” odds of being at a high risk of “common mental disorders”, such as anxiety or depression, compared to those living further than 50km away. The link was stronger within socioeconomically deprived communities, indicating that access to blue spaces could reduce health inequalities.“The doctors of yesteryear had the right idea when they would prescribe the coastline as a type of medicine,” says Jolyon Sharpe, a countryside officer at Cornwall Council. “Beach cleaning can be done beautifully in isolation; it can be very therapeutic, almost meditative,” says Sharpe. The melange of sounds – crashing waves, blustering wind and seagulls crooning – is pivotal. “Everything you hear is a sensory overload, and that’s incredibly good for your mental wellbeing.” And, when you add an altruistic element, such as cleaning, the satisfaction is twofold.“One thing that brings everyone together is that the coastline of Cornwall is beautiful,” says Sharpe. “The key thing is the beach is for everyone to enjoy, but we’ve got to protect it. Litter picking is one really simple way that everybody can give back to the environment that they love.”TopicsPollutionThe ObserverPlasticsCornwallCornwall holidaysfeaturesReuse this content

Plastic pollution could make much of humanity infertile, experts fear

Since the start of the 2020s, humanity has faced worldwide calamity after worldwide calamity, all of them raising questions about our survival as a species. The COVID-19 pandemic has already claimed millions of lives and not yet finished its rampage. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has raised the specter of nuclear holocaust, which many assumed has subsided with the end of the Cold War. Even as these problems worsen, climate change continues to quietly creep along in the background, overheating the planet for future generations.

Yet what if, on top of all these things, there is an even more dystopian crisis in the offing — one in which humans are no longer able to reproduce without artificial help because we have filled the environment with chemicals that have altered our bodies?

Scientists believe this is not only possible, it is likely to happen within our lifetimes.

Understanding why involves three statistics: First, that a human male who has fewer than 15 million sperm per milliliter is considered infertile; second, that in the 1970s sperm counts in Western countries (where there is available data) showed an average of 99 million sperm per milliliter; and third, that this number had dropped to 47 million sperm per milliliter by 2011. Scientists agree that plastic pollution is a likely culprit.

The trailblazer here has been Dr. Shanna Swan, a professor of environmental medicine and public health at Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York City, whose most famous book has a conveniently self-explanatory title: “Count Down: How Our Modern World Is Threatening Sperm Counts, Altering Male and Female Reproductive Development, and Imperiling the Future of the Human Race.”

The main culprit is believed to be chemicals within everyday plastics known as endocrine disruptors. These chemicals, including a range of phthalates and bisphenols, are literally inescapable. They can be found in the dishware, food cans and containers from which you eat your food, and in the water bottles and other plastic receptacles from which you drink. They are in virtually all of your commonly used household electronics, your eyeglass lenses, your furniture and even on any commercial receipts that come from a thermal printer. Because endocrine disruptors are in pesticides, they have also entered the foods that we eat thanks to the agriculture industry. Even without pesticides, though, we would still wind up eating these endocrine disruptors. Microplastics — that is, plastic particles which are five millimeters or less across or in length — have entirely covered the planet. Animals accidentally eat microplastics all the time and plants regularly absorb them through their roots. Humans themselves ingest the rough equivalent of a credit card’s worth of plastic each week.

Want more health and science stories in your inbox? Subscribe to Salon’s weekly newsletter The Vulgar Scientist.

“First society needs to identify and agree we have a very serious problem; this takes time like climate change,” Bjorn Beeler, international coordination at IPEN — International Pollutants Elimination Network — told Salon by email. “Scientists knew in the 1970s/80s climate change was coming due to [greenhouse gas] emissions, and now we are discussing adaptation and climate crisis 40+ years later (late). So to curb the threat, we need to define the problem, then turn off the toxic chemical tap.”

Even if that happens, however, there is so much plastic everywhere that humanity simply cannot escape at least some of the consequences from this constant exposure. Swan told Salon by email that federally funded assisted reproduction technology — something currently provided in only one country, Israel — will help in making sure that people impacted by this pollution can still have children.

“Disadvantaged communities are more highly exposed to risky chemicals and they are more affected (on average) by the same level of exposure,” Swan wrote to Salon. “So, it’s a ‘triple whammy’ for these communities.”

John Hocevar, the Oceans Campaign Director for Greenpeace USA, explained to Salon by email that “reduced sperm counts and other reproductive ailments disproportionately impact low income communities and people of color. Poor communities are more likely to be located closest to incinerators and landfills, as well as refineries. Access to expensive treatments to compensate for reproductive health issues are not equitable today, and even with an optimistic view of the US political landscape it is clear that this problem is not going to go away any time soon.”

Not surprisingly, the plastic industry and others that rely on these chemicals dispute that the endocrine disruptors are responsible for the drop in sperm counts. As Beeler pointed out, they will provide alternate data just like industries do when they dispute the validity of climate science. Hocevar added that plastic companies also have an advantage because plastics are so pervasive that “it is difficult to design controls where plastic can be excluded as a factor. The plastic industry uses this terrible situation to try to claim that we don’t have enough evidence to be sure that these chemicals are dangerous.”

And, to be clear, there are other factors that no doubt contribute to fertility issues for both men and women: Obesity, smoking, binge drinking, stress. Still, the science about endocrine disruptors is clear.

“Chemicals in plastic (phthalates, bisphenols and others) as well as pesticides, lead and other environmental exposures are linked to impaired reproduction including sperm count and quality,” Swan told Salon. “Some, like phthalates and BPA, have a short half-life in the body (4-6 hours), so it is possible to reduce the body’s exposure if we can stop using products containing these.” At the same time, society will have to exercise collective will and make sure that the most vulnerable among us are not left behind.

“Low-income communities can’t afford to ‘buy their way out’ of the problem by purchasing organic, unprocessed foods, safer cosmetics etc. (which are more expensive),” Swan explained. “But the ‘mass infertility scenario’ is a threat to everyone (not just the disadvantaged).”

Read more on plastic pollution:

Plastic pollution could make much of humanity infertile, experts fear

Since the start of the 2020s, humanity has faced worldwide calamity after worldwide calamity, all of them raising questions about our survival as a species. The COVID-19 pandemic has already claimed millions of lives and not yet finished its rampage. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has raised the specter of nuclear holocaust, which many assumed has subsided with the end of the Cold War. Even as these problems worsen, climate change continues to quietly creep along in the background, overheating the planet for future generations.

Yet what if, on top of all these things, there is an even more dystopian crisis in the offing — one in which humans are no longer able to reproduce without artificial help because we have filled the environment with chemicals that have altered our bodies?

Scientists believe this is not only possible, it is likely to happen within our lifetimes.

Understanding why involves three statistics: First, that a human male who has fewer than 15 million sperm per milliliter is considered infertile; second, that in the 1970s sperm counts in Western countries (where there is available data) showed an average of 99 million sperm per milliliter; and third, that this number had dropped to 47 million sperm per milliliter by 2011. Scientists agree that plastic pollution is a likely culprit.

The trailblazer here has been Dr. Shanna Swan, a professor of environmental medicine and public health at Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York City, whose most famous book has a conveniently self-explanatory title: “Count Down: How Our Modern World Is Threatening Sperm Counts, Altering Male and Female Reproductive Development, and Imperiling the Future of the Human Race.”

The main culprit is believed to be chemicals within everyday plastics known as endocrine disruptors. These chemicals, including a range of phthalates and bisphenols, are literally inescapable. They can be found in the dishware, food cans and containers from which you eat your food, and in the water bottles and other plastic receptacles from which you drink. They are in virtually all of your commonly used household electronics, your eyeglass lenses, your furniture and even on any commercial receipts that come from a thermal printer. Because endocrine disruptors are in pesticides, they have also entered the foods that we eat thanks to the agriculture industry. Even without pesticides, though, we would still wind up eating these endocrine disruptors. Microplastics — that is, plastic particles which are five millimeters or less across or in length — have entirely covered the planet. Animals accidentally eat microplastics all the time and plants regularly absorb them through their roots. Humans themselves ingest the rough equivalent of a credit card’s worth of plastic each week.

Want more health and science stories in your inbox? Subscribe to Salon’s weekly newsletter The Vulgar Scientist.

“First society needs to identify and agree we have a very serious problem; this takes time like climate change,” Bjorn Beeler, international coordination at IPEN — International Pollutants Elimination Network — told Salon by email. “Scientists knew in the 1970s/80s climate change was coming due to [greenhouse gas] emissions, and now we are discussing adaptation and climate crisis 40+ years later (late). So to curb the threat, we need to define the problem, then turn off the toxic chemical tap.”

Even if that happens, however, there is so much plastic everywhere that humanity simply cannot escape at least some of the consequences from this constant exposure. Swan told Salon by email that federally funded assisted reproduction technology — something currently provided in only one country, Israel — will help in making sure that people impacted by this pollution can still have children.

“Disadvantaged communities are more highly exposed to risky chemicals and they are more affected (on average) by the same level of exposure,” Swan wrote to Salon. “So, it’s a ‘triple whammy’ for these communities.”

John Hocevar, the Oceans Campaign Director for Greenpeace USA, explained to Salon by email that “reduced sperm counts and other reproductive ailments disproportionately impact low income communities and people of color. Poor communities are more likely to be located closest to incinerators and landfills, as well as refineries. Access to expensive treatments to compensate for reproductive health issues are not equitable today, and even with an optimistic view of the US political landscape it is clear that this problem is not going to go away any time soon.”

Not surprisingly, the plastic industry and others that rely on these chemicals dispute that the endocrine disruptors are responsible for the drop in sperm counts. As Beeler pointed out, they will provide alternate data just like industries do when they dispute the validity of climate science. Hocevar added that plastic companies also have an advantage because plastics are so pervasive that “it is difficult to design controls where plastic can be excluded as a factor. The plastic industry uses this terrible situation to try to claim that we don’t have enough evidence to be sure that these chemicals are dangerous.”

And, to be clear, there are other factors that no doubt contribute to fertility issues for both men and women: Obesity, smoking, binge drinking, stress. Still, the science about endocrine disruptors is clear.

“Chemicals in plastic (phthalates, bisphenols and others) as well as pesticides, lead and other environmental exposures are linked to impaired reproduction including sperm count and quality,” Swan told Salon. “Some, like phthalates and BPA, have a short half-life in the body (4-6 hours), so it is possible to reduce the body’s exposure if we can stop using products containing these.” At the same time, society will have to exercise collective will and make sure that the most vulnerable among us are not left behind.

“Low-income communities can’t afford to ‘buy their way out’ of the problem by purchasing organic, unprocessed foods, safer cosmetics etc. (which are more expensive),” Swan explained. “But the ‘mass infertility scenario’ is a threat to everyone (not just the disadvantaged).”

Read more on plastic pollution:

A world changing idea: Capturing methane to reduce plastic use

Carbon dioxide gets a lot of attention. But we also need to talk about methane.

[Photo: courtesy AirCarbon]

By

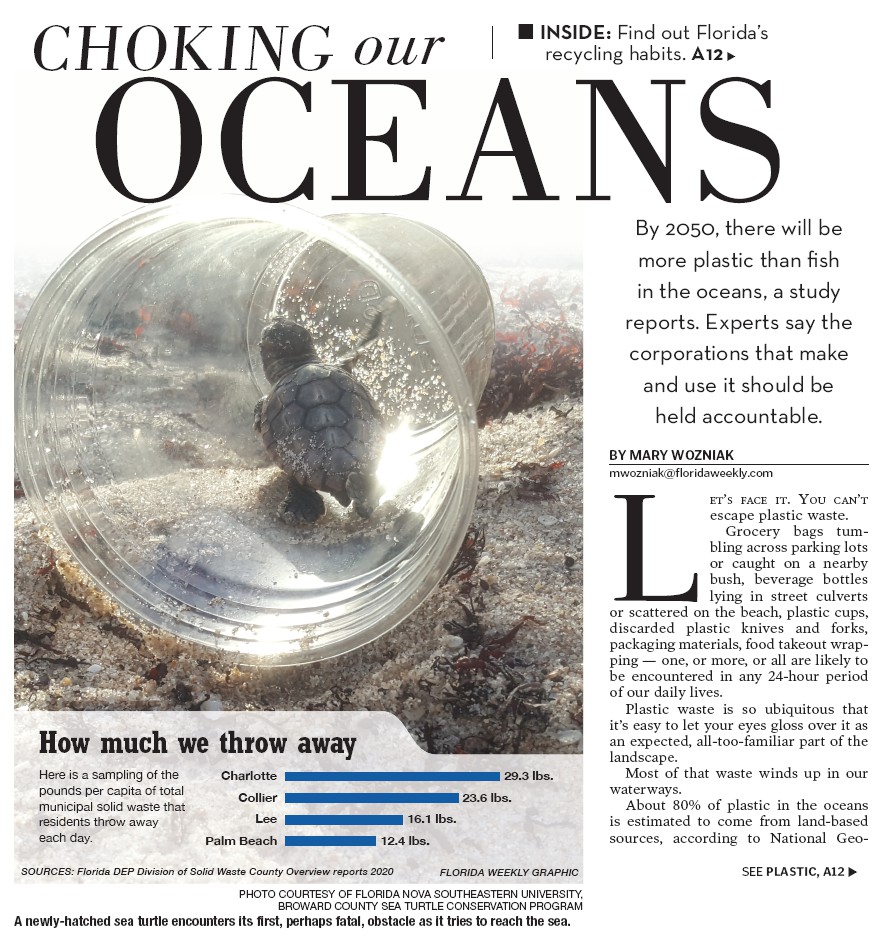

Choking our oceans

A newly-hatched sea turtle encounters its first, perhaps fatal, obstacle as it tries to reach the sea. PHOTO COURTESY OF FLORIDA NOVA SOUTHEASTERN UNIVERSITY, BROWARD COUNTY SEA TURTLE CONSERVATION PROGRAM

LET’S FACE IT. YOU CAN’T escape plastic waste. Grocery bags tumbling across parking lots or caught on a nearby bush, beverage bottles lying in street culverts or scattered on the beach, plastic cups, discarded plastic knives and forks, packaging materials, food takeout wrapping — one, or more, or all are likely to be encountered in any 24-hour period of our daily lives.

Plastic waste is so ubiquitous that it’s easy to let your eyes gloss over it as an expected, all-too-familiar part of the landscape.

Choking our oceans

A newly-hatched sea turtle encounters its first, perhaps fatal, obstacle as it tries to reach the sea. PHOTO COURTESY OF FLORIDA NOVA SOUTHEASTERN UNIVERSITY, BROWARD COUNTY SEA TURTLE CONSERVATION PROGRAM

LET’S FACE IT. YOU CAN’T escape plastic waste. Grocery bags tumbling across parking lots or caught on a nearby bush, beverage bottles lying in street culverts or scattered on the beach, plastic cups, discarded plastic knives and forks, packaging materials, food takeout wrapping — one, or more, or all are likely to be encountered in any 24-hour period of our daily lives.

Plastic waste is so ubiquitous that it’s easy to let your eyes gloss over it as an expected, all-too-familiar part of the landscape.

Striking images of plastic pollution in the Mediterranean

As part of Monaco Ocean Week, the Ramoge Agreement presented an awareness-raising video on the impact of marine litter, entitled “Frisson dans les abysses” (Chills in the depths) »The images are startling. Plastic waste, as far as the eye can see, in the heart of the Monaco canyon, 30km off the Principality’s coast. The images were shot in 2018, but are practically unchanged, four years later.

[embedded content]

The Ramoge Agreement is an intergovernmental cooperation agreement between the French, Italian and Monegasque States for the preservation of the marine environment signed in 1976. The organisation wanted to highlight once again the seriousness of plastic pollution for our oceans by unveiling this shocking video, which shows exploration campaigns carried out in the underwater canyons.

Images captured by a remote-controlled robot more than 2,000 metres down.

The images, captured by a remote-controlled robot (ROV) off Monaco, show the impressive amount of plastic waste accumulated at depths of over 2,000 metres. Waste from the land, dumped in the countryside, carried by rivers to the sea, then by the current to the Monaco canyon.

SEE ALSO: COP26: Prince Albert II calls for a real commitment to the protection of the oceans

As Monaco Ocean Week, a unifying event about ocean preservation, is being held in the Principality since Monday, this video could well feature in the different conferences planned throughout the week.