Researchers modeled the journey of microplastics released in wastewater treatment plant effluent into rivers of different sizes and flow speeds, focusing on the smallest microplastic fragments — less than 100 microns across, or the width of a single human hair.The study found that in slow-flowing stream headwaters — often located in remote, biodiverse regions — microplastics accumulated quicker and stayed longer than in faster flowing stretches of river.Microplastic accumulation in sediments could be the ‘missing plastic’ not found in comparisons of stream pollution levels with those found in oceans. Trapped particles may be released during storms and flood events, causing a lag between environmental contamination and release to the sea.A few hours in stream sediments can start to change plastics chemically, and microbes can grow on their surfaces. Most toxicity studies of microplastics use virgin plastics, so these environmentally transformed plastics pose an unknown risk to biodiversity and health. Tiny fragments of plastic can linger for years in slow flowing streams and rivers, according to the results of a computer modeling study published in Science Advances last month.

As tributaries and rivers flow from source to estuary, through rural, urban and industrial landscapes, they have lots of opportunities to pick up plastic fragments and carry them to the ocean, but we still know relatively little about what happens along the way, how long this turbulent journey might take, or what the environmental impacts may be.

“There are a lot of physical processes that take place in a stream,” said lead author Jennifer Drummond, a research fellow at the University of Birmingham, UK.

Plastic bags litter a river bank in Europe. Photo credit: Ivan Radic on VisualHunt.com

Models of microplastic transport that take into account gravitational forces alone predict that very small particles will stay afloat and be carried swiftly to the ocean. But small fragments can also be influenced by the dynamics of water movement at the interface between flowing water and sediment, called the ‘hyporheic’ zone. Plastic particles can be carried downwards from the surface by turbulence, while small variations in pressure can force water into the sediments, depositing microplastics there. These exchanges between flowing water and river sediments are “the piece that was missing,” from previous explanations of microplastic transport, Drummond explained.

The researchers modeled the journey of microplastics released from wastewater treatment into rivers of different sizes and flow rates, focusing on the smallest microplastic fragments — less than 100 microns across, or the width of a single human hair — which are most strongly influenced by pressure differences between the surface water and the hyporheic zone. They found that heretofore ignored hyporheic exchange processes can draw microplastics into the sediments at rate of 5% per kilometer (8% per mile) on average.

“This kind of exchange hadn’t been modeled and accounted for previously, and it seems to be an important one,” said Sherri Mason, Director of Sustainability at Penn State Erie in Pennsylvania, U.S., who was not involved in the study. A deeper understanding of hyporheic processes, “moves us closer to having better global accounting of where all of the plastic is,” she added.

Particles embedded in sediments will remain trapped as long as the river flow stays relatively low, and the model showed that for a 10 kilometer stretch of river, they could spend 30 hours on average, and up to 3 years in the sediments. Slower-moving streams and headwaters captured more microplastics and for longer: 8% of plastic particles entered these river sediments per kilometer and low-flow conditions could keep them there for up to 7 years. This suggests that storms and flood events, which are becoming more severe and more frequent as a result of climate change, could trigger the release of millions of accumulated fragments of microplastic from river sediments.

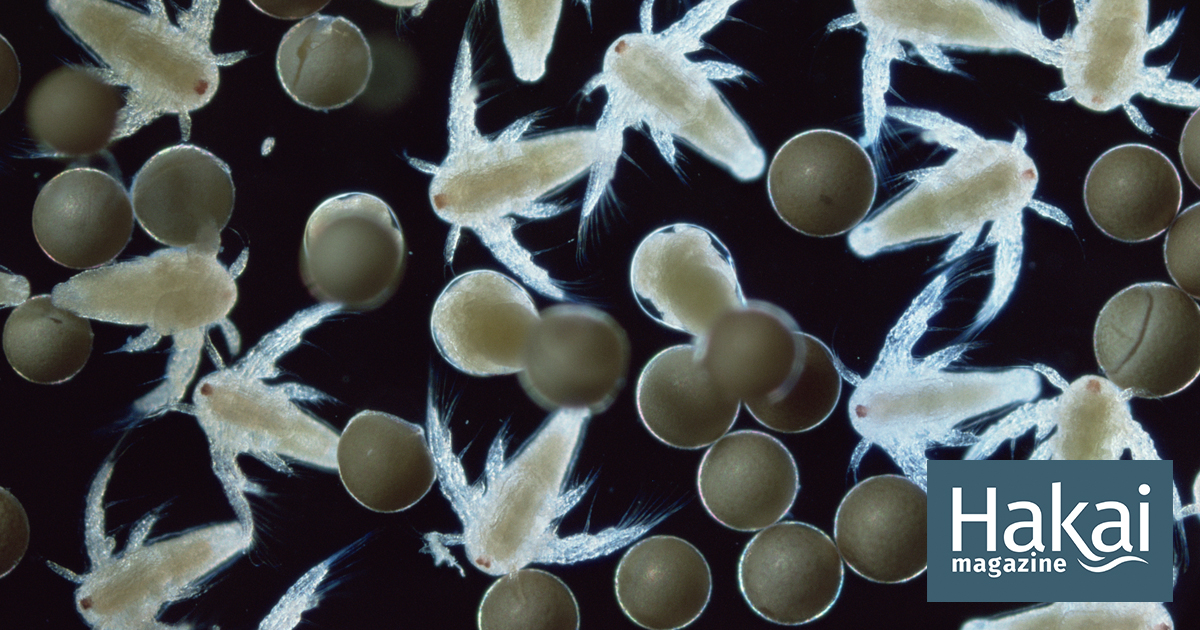

Microplastics range in size from 5mm to tens of microns across. The smallest fragments, less than 100 microns, were thought to pass along rivers quickly to the sea because of their buoyancy. But modeling shows that small scale water dynamics can drive these particles into sediments and trap them there for long periods of time. Image credit: Oregon State University on VisualHunt.

Remobilized microplastics might end up deposited on flood plains as storm waters retreat or be carried onwards downstream to the ocean. “The time in between [floods] will really determine how much [plastic] is remobilized versus how much can stay and accumulate,” explained Drummond.

The team noted that the rate of microplastic accumulation in the model agreed closely with a published dataset from the Roter Main River in Germany. Sediment cores collected downstream of a wastewater plant there contained between 4,500 and 30,000 plastic fragments smaller than 50 microns across for every kilogram of dried sediment, close to the model’s prediction of 10,000 – 50,000 particles per kilogram.

“This is an important and sophisticated piece of research that helps us understand the processes involved in the accumulation of microplastics on riverbeds,” said Jamie Woodward, professor of physical geography at the University of Manchester in the UK. He praised the study’s focus on microplastics smaller than 100 microns, explaining that “the finest microplastics may pose the most serious ecological risk.”

Microplastics originate in a variety of sources, including degrading plastic bottles and other packaging, fragments from synthetic clothing, as well as industrial effluent and agricultural waste that make their way through wastewater treatment plants or via runoff to tributaries, rivers, and eventually the ocean. Image credit: Ivan Radic on Visualhunt.com.

Finding the missing plastic

Sediment-bound microplastics could be the source of so-called ‘missing plastic’ identified in comparisons of the rate of plastic release from known sources with measurements of microplastic contamination in the oceans. “It’s been postulated that some of that missing plastic is probably in sediments,” said Mason, and this study confirms that hyporheic exchange is a mechanism that can pull very small microplastic fragments into the sediment and hold them there for hours or days.

Even a few hours in the sediment can fundamentally change a plastic particle: chemical processes can start to break them into smaller fragments or convert them into gases, and they can become food or territory for living organisms. “Many different chemicals and microbes can attach to these plastic particles,” explained Drummond, and the smaller the particle, the larger the surface area for microbes and chemicals to attach.

To insects and fishes living in and around the rivers, microbe- and chemical-laden plastic particles can look like an appetizing snack. “The channel bed is a critical part of the riverine ecosystem where many creatures live, feed and reproduce,” said Woodward. “If the riverbed is contaminated with microplastics, there is a high chance that some of those microplastic particles will enter the food chain.”

The Roter Main River in southern Germany is a major Rhine tributary. Sediment cores collected downstream of a wastewater plant contain 4,500 – 30,000 microplastic fragments per kilogram, agreeing closely with the present study’s modeled predictions. Image credit: Public domain by GertGrer on Wikimedia.

Wastewater treatment plants, like this one in Moscow, Russia, are a major source of microplastic pollution flowing into rivers because many particles are too small to be filtered out. The researchers modeled the journey of microplastic particles from these consistent sources to understand how small scale water dynamics affected microparticle movement. Image credit: A.Savin on Wikimedia Commons.

But how much that might impact wildlife or people is uncertain. Much of our understanding of how microplastics affect living organisms comes from laboratory studies of virgin plastic that hasn’t undergone these chemical and biological changes. “By the time they reach the ocean, [the plastic particles] are different,” said Drummond, and “it’s these environmentally transformed plastics,” that are lingering in freshwater ecosystems and eventually being carried to the ocean, posing an unknown risk to freshwater and marine biodiversity.

Headwaters are often in more remote, high biodiversity regions, but their slow-flowing waters are more likely to drive microplastics into the sediment and keep them there for longer. This means “there’s more time for these particles to really incorporate into the environmental matrix,” said Drummond, with potential knock-on effects for the entire food chain.

“The quality of the riverbed environment affects the whole riverine ecosystem,” remarked Woodward. “The longer these particles are stored in this environment, the greater the risk.”

Plastics can take hundreds of years to fully decompose. The United Nations is meeting this month to begin developing a global plastics waste treaty. Ivan Radic on Visualhunt.com.

Plastic pollution has helped push us over a planetary boundary

Globally, our indulgent use and disposal of plastics has now exceeded safe levels, helping to push us past a planetary boundary for chemical pollution and potentially setting the Earth life support system on a path towards a new, less habitable state.

In addition, it’s believed that overshooting one planetary boundary can destabilize another, like a line of falling dominoes: Escalating climate change — an already infringed planetary boundary — is bringing with it more severe and frequent extreme weather events, which could have complex effects on microplastic transport and retention in rivers. More intense and frequent droughts will reduce stream flows, depositing more microplastic fragments into sediments where they can make their way into the food chain, with potentially unforeseen consequences for the biodiversity planetary boundary. Conversely, increasingly common and severe storms and floods can remobilize those trapped fragments — and any microbes or chemicals attached to their surface — allowing them to be carried to the ocean, where they may impact marine life.

Sediment-trapped microplastics will continue to extend the lag between environmental contamination in rivers and release of pollutants into the ocean, which could slow clean-up efforts. “If we were to stop all plastic production today, how much longer are we going to be seeing this stuff leaching into the environment?” Mason questioned. “There’s always a delayed reaction when it comes to the environment.”

“It really makes you think,” said Drummond, “Every time you’re using plastic, it very likely ends up in your rivers and it’ll be there for a very, very long time.”

Citation:

Drummond, J. D., Schneidewind, U., Li, A., Hoellein, T. J., Krause, S., & Packman, A. I. (2022). Microplastic accumulation in riverbed sediment via hyporheic exchange from headwaters to mainstems. Science advances, 8(2), eabi9305. DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.abi9305.

Banner image: Plastic waste has become ubiquitous in the global environment since the years following World War II. Photo credit: Ivan Radic on VisualHunt.com

FEEDBACK: Use this form to send a message to the author of this post. If you want to post a public comment, you can do that at the bottom of the page.

Headwaters of Pennsylvania’s Lehigh River in the U.S. Headwaters are often found in remote and biodiverse regions, but the study’s model suggests they are particularly vulnerable to accumulating microplastics because of their low flow conditions — with unknown impacts on life there. Image credit: Nicholas_T on Flickr.

Chemicals, Environment, Green, Health, Microplastics, Nature And Health, Ocean Crisis, Oceans, Plastic, Poisoning, Pollution, Research, Rivers, Toxicology, Waste, Water, Water Crisis, Water Pollution

Print