As we look to transition from fossil to bio-based materials, fungi are becoming the ultimate biodegradable building blocks for furniture, fashion, housing and beyond.

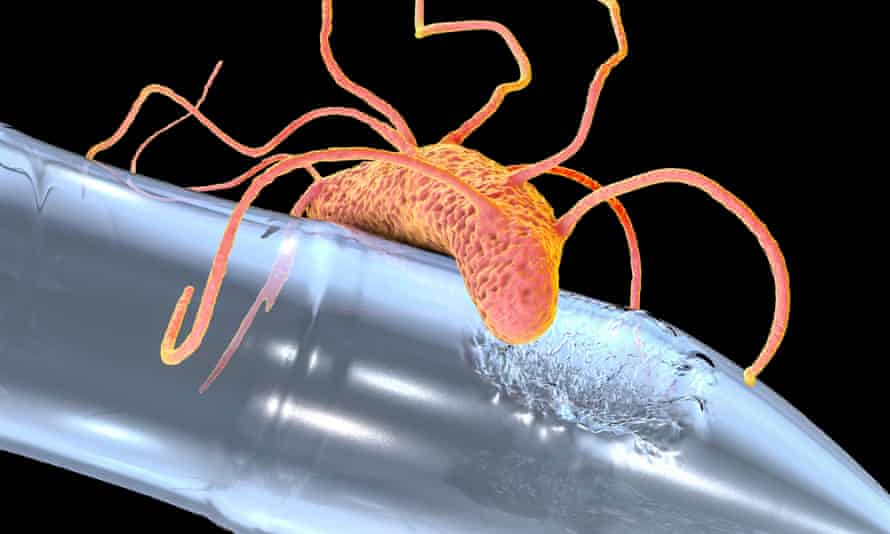

Mycelium, the silky thread that binds fungus, is being adapted to create everything from shoes to coffins to packaging and robust building materials. Best of all, it literally feeds on trash and agricultural byproducts, detoxifing them along the way.

The biodegradable material that is also grown vertically to save space and uses little water, has emerged as a low emission, circular economy solution in the bid to transition from extractive, carbon-based products.

There are up to five million types of fungus that constitute a “kingdom on their own,” says Maurizio Montalti, a Dutch-based designer and researcher who has been working with mycelium for a decade.

Fungi are the “fundamental agents that enable the transformation of not only nutrition but also information across living systems. We couldn’t live without it,” said Montalti of what has also been called natures’s internet.

Having experimented with mycelium furniture design, in 2018 Montalti founded Mogu, a company commercializing fungi-based bio-material products — including sound-absorbing tiles created from mycelium grown on corn crop refuse, rice straw, spent coffee grounds, discarded seaweed and even clam shells.

But fungi aren’t changing the world just yet.

“There is a lot of excitement these days when talking about mycelium,” Montalti said, adding that the challenge is in designing a “product that works and can compete in the market.”

And although shoe and apparel giant Adidas as well as fashion labels Stella McCartney and Gucci have all recently hopped on the fungi bandwagon to try and meet that challenge, mycelium is yet to go mass-scale.

Here are four products that could herald the start of a revolution.

1. Mycelium ‘living cocoon’ coffins

“Are you waste or compost?” That is the question according to Netherlands-based mycelium coffin manufacturer, Loop. The company is offering the dead a chance to birth new life via their “living cocoon” coffin, which it claims was the first of its kind.

As bodies decompose within a fully compostable mycelium cocoon, they can become part of the solution to reviving biodiversity that has depleted to the point where more than a million species are at risk of extinction.

“To be buried, we cut down a tree, work it intensively and try to shut ourselves off as well as possible from microorganisms,” Loop said in a statement in reference to conventional coffins. “And for those that don’t want to be buried, we waste our nutrient-rich body by burning it with cremation, polluting the air and ignoring the potential of our human body. It’s as if we see ourselves as waste, while we can be a valuable part of nature.”

2. Mushroom ‘leather’ shoes

Mycotech, based in Bandung, Indonesia, was growing gourmet mushrooms in 2012 before it shifted its business to use fungi to create a sustainable alternative to leather products, especially shoes.

Founder, Adi Reza Nugroho says it has great environmental advantages over traditional leather. “We consume less water, we don’t have to kill animals, we can do vertical farming so we can save some space,” he said, adding that it also produces fewer emissions and requires none of the chemicals used in plastic-based materials.

Feeding on agricultural waste such as sawdust, it only takes the mycelium a few days to grow to the point where it is ready to be harvested, tanned and further processed. The resulting material is breathable, flexible, robust and can last for years. While Mycotech is still creating limited runs of its fungi shoes, the company has orders up until 2027.

And this relatively small-scale start-up is not alone. While leather continues to dominate Adidas’ sneaker lines, the German company is now also marketing mycelium shoes. Released in April, the Stan Smith Mylo is made using the brand’s “Mylo” mycelium material.

Fungi-based footwear is also being touted by eco-conscious grassroots designers because the shoes can literally biodegrade — as illustrated by these Mycoflex-based slippers designed by Charlotta Aman.

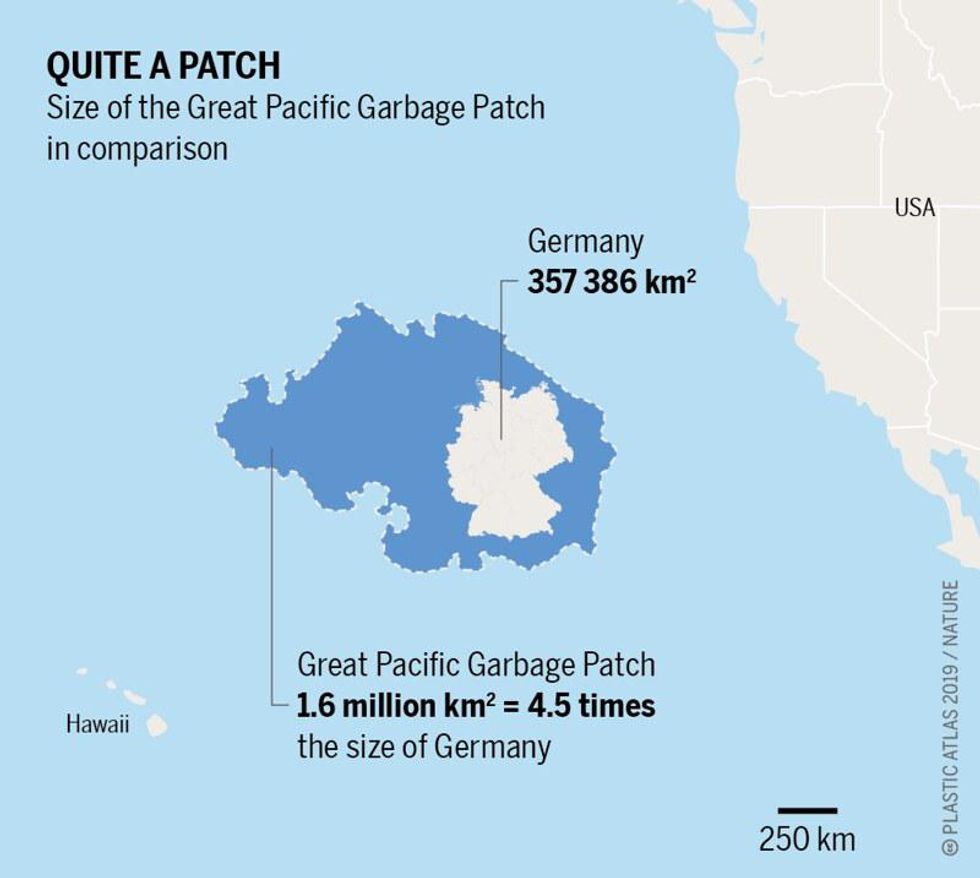

3. Transforming plastic and toxic waste

Since they feed on trash, mushrooms can also detoxify our waste and transform it into usable materials that are non-extractive, offering a neat solution for closing the loop on unrecylable plastic, for example.

Established in 2018, US-based Mycocycle uses fungi to remove toxins from building materials like asphalt or petrochemical-based waste.

“We are actually using mushrooms to cycle these toxins, make them non-toxic and available for reuse in a closed loop economy,” said company founder, Joanne Rodriguez.

A response to the fact that 85% of landfill space in the US has already been used up, Mycocycle aims to help in the shift to zero waste by decontaminating toxic building materials like asphalt that previously could not be reused.

Mycocycle claims that its trash-fed mycelium is fire and water-resistant and can be manufactured into a host of new products such as styrofoam, insulation, packaging and building materials.

“We take trash and make treasure, decarbonizing waste and creating a new value stream in the circular economy,” said Rodriguez.

4. A biodegradable building block

A fully compostable, zero-emissions mushroom tower called the Hy-Fy was constructed with 10,000 mycelium bricks in New York back in 2014. Numerous prototypes have been built since but mushroom-building largely remains in the conceptual stage.

“Co-create with fungi,” is the mantra for the My-Co Space, a mycelium tiny house currently being exhibited in Frankfurt’s Metzlerpark.

The compostable mushroom My-Co Space is currently on display in Frankfurt. It can also be booked for overnight stays

Designed for two occupants, the facade of the 20-square-meter structure has a plywood frame thatched in honeycomb-shaped mycelium blocks grown with a mushroom straw substrate. The intimate, organic shape plays on the fundamental interrelation between humans and fungi.

“We want to transform dead plant matter, which comes from agriculture or from forestry, and we want to transform this into composite materials. And we do this with fungi,” explains Vera Meyer, a biotechnology professor at the Technical University of Berlin and founder of the MY-CO-X collective that created My-Co Space.

For Meyer, fungi are the “most important microorganisms” that can help make the transition from fossil to bio-based resources.