The dense black smoke from a fire at a plastics recycler in Richmond, Indiana, that began Tuesday afternoon and continued burning on Wednesday, forcing the evacuation of 2,000 nearby residents, was dramatic, but far from an isolated incident in the world of facilities that store or recycle vast quantities of plastic waste.

There are hundreds of such fires in the United States and Canada every year and most of them never make the news, said Richard Meier, a private fire investigator in Florida who worked 24 years as a mechanical engineer in manufacturing, including in plastics companies.

“These plastics, most of them are derived from oil. They are petrochemicals and they have the same propensity for burning once ignited,” Meier said.

So far, in Richmond, in eastern Indiana between Indianapolis and Dayton, Ohio, local health officials say the biggest threat to the public is from breathing particulates in the smoke.

But as firefighters and residents there are now experiencing, the toxic chemicals plastic fires can release also pose significant threats.

“There can be a lot of nasty things that come along with burning plastics. Polyurethane can release hydrogen cyanide,” Meier said, referring to the chemical warfare agent.

“Dioxins come from burning plastics,” he said, referring to a group of highly toxic chemicals that can cause cancer, reproductive and developmental problems, damage to the immune system and interfere with hormones.

“That’s why firefighters wear full respiratory gear when fighting a plastic fire, with an air tank on their back,” Meier said.

On Wednesday, Richmond Mayor Dave Snow told reporters the fire occurred at a plastic waste collection business that city officials have been trying to clean up for several years.

“We were aware what was operating (there) was a fire hazard,” Snow said. “The business owner is responsible for all this.”

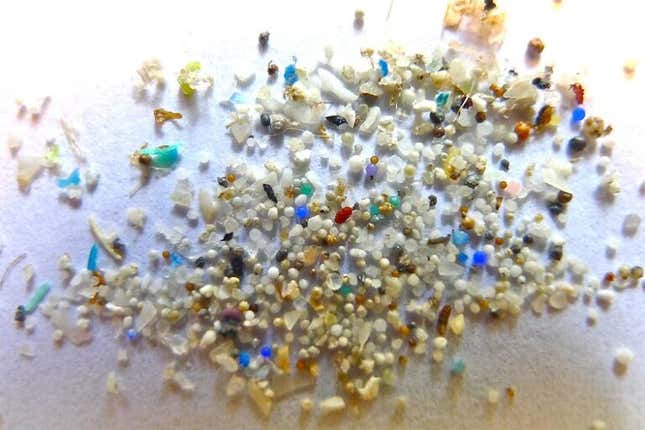

The fire raised new and old concerns about the global plastics crisis that is overwhelming landfills and collection sites, choking the oceans and depositing microplastics inside the bodies and bloodstreams of wild animals and humans alike. Although plastics are ubiquitous in much of modern life, the United Nations and many of its member countries now view them as posing a health and climate threat thoughout their lifecycle, and are working on a plastics treaty in an effort to stop their proliferation and clean them up.

In Richmond, City Councilman Ron Oler said as much as 70 million pounds of waste plastic was stored inside and outside several buildings on the burning property, which is near a residential area.

He said the plastics there were the hardest types to recycle and had been piling up ever since China stopped accepting most plastic waste —including from Richmond—under a policy called National Sword.

“This guy was buying up scrap plastic and selling it to China,” Oler said. When the China market dried up, so did his business prospects, he added.

But the plant’s owner kept receiving it and storing it, Oler said.

“Our biggest fear has been there would be a fire because there is so much plastic,” he said. Cleanup efforts, however, have been tied up in the courts, he said.

Oler said the fire itself has been terribly disruptive, requiring an evacuation zone of one-half mile, which affected at least 2,000 residents. It could burn for days, officials said.

“This is Richmond’s East Palestine moment,” he said, referring to the Feb. 3 train derailment in eastern Ohio and the controlled release and burning of five railcars of vinyl chloride, a cancer-causing chemical used to make PVC plastic.

At a Wednesday press conference, Christine Stinson, the executive director of the Wayne County Health Department, said air monitoring has revealed the biggest concern to be particulates in the smoke.

“Just standing here, you can see how close we are to the fire, my throat is starting to get a little sore,” she told reporters, several blocks from the charred and burning remains of the recycling business, with smoke still rising as a backdrop.

EPA officials said they will continue air monitoring for particulates and several types of chemicals, including volatile organic compounds, benzene, chlorine and hydrogen cyanide.

China’s National Sword policy rocked global recycling markets, including across the United States.

“I will bet there are almost a hundred of these facilities laying around the United States with giant stockpiles of plastics,” said Jane Williams, executive director of the environmental group California Communities Against Toxics. “There is no way to recycle it because it’s not recyclable.”

Since China adopted National Sword, a lot of plastic waste has been sent to landfills or burned in incinerators, said Jan Dell, a chemical engineer who has worked as a consultant to the oil and gas industry and now runs The Last Beach Cleanup, a nonprofit that fights plastics pollution and waste.

She’s been so concerned about fire threats from old and new stockpiles that she’s been tracking most of those plastic fires that actually do make the news.

She has counted 70 and mapped their locations in several countries since 2019.

“This is a horrific problem because plastic waste is highly flammable and at these operations, not all of them have proper health and safety management,” she said. “They are sketchy operators.”

With the chemical and plastics industry promoting more recycling, and selling recycling to the public as “clean and green,” plastic fires at recycling plants illustrate a contradictory and, she said, more realistic image of the industry.

She and other environmentalists say that fires at plastic recycling operations also highlight a threat from the American Chemistry Council’s national push to persuade state legislatures to regulate so-called “advanced recycling” operations as manufacturing and not solid waste management, limiting the need for waste management permits and regulations.

The industry uses the term “advanced’’ to include recycling processes that convert plastic waste into chemical ingredients for new plastic products or fuel, using high heat and other chemicals. But these advanced recycling plants, which many environmentalists describe as essentially plastics incinerators, also typically stockpile waste plastics onsite.

In fact, a Brightmark advanced, or chemical, recycling plant in northeast Indiana experienced a fire in 2021 that also sent a large plume of black smoke into the air, according to a local television station report.

Kansas on Monday became the 23rd state to pass such legislation categorizing advanced recycling as a manufacturing process, subject to far less regulation than waste disposal or incineration, according to the American Chemistry Council. Indiana lawmakers passed their own version of such a law, Senate Bill 472, in March, and on Wednesday the Indiana chapter of the Sierra Club urged Indiana Gov. Eric Holcomb to veto it.

Keep Environmental Journalism Alive

ICN provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going.

The Richmond facility is not an advanced recycling plant. But Oler, the city councilman, said he believes its owner has been waiting on something like chemical or advanced recycling to buy its mountain of plastic waste. He said the stockpile included those plastics numbered 3-7, the hardest types of plastics to recycle through more conventional means.

The Richmond fire, and others at plastic recycling facilities, show that any increase in plastic recycling will need to be accompanied by an increase in fire prevention efforts, said Meier, the private fire inspector. Facilities that hold highly flammable materials like plastic will need, for example, more robust fire suppression systems, he said.

But Dell said she believes legislative efforts in mostly Republican states to classify advanced recycling facilities as manufacturing also have the potential to reduce safety requirements regarding fire prevention when officials should be taking steps to increase them.

“The fact that they are trying to (redefine) these as safe assembly plants is illegitimate,” Dell said. “It leaves communities holding the bag.”

EPA Administrator Michael Regan.

EPA Administrator Michael Regan.