In March, the United Nations’ Environment Assembly adopted a landmark resolution, supported by 175 countries, to end plastic pollution with a legally binding treaty.

Negotiations, expected to take two years, began this week. As a group of nine international experts on plastic pollution from eight countries, we’ve recently argued in a letter to the journal Science that this treaty must cap plastic production and regulate the chemicals they contain.

Here’s why.

Plastic impacts on future generations

In the past 100 years, humanity has introduced an immense amount and variety of new chemicals and plastics to the planet. The current global plastic production is roughly 450 million tons per year. If we add up all the plastics produced so far, their weight would surpass the mass of all land and marine animals. Annual production is predicted to double by 2045, when today’s preschoolers are adults. They will likely live in a world of fragile ecosystems and a changing climate. If plastic pollution continues unabated, it will exacerbate these problems.

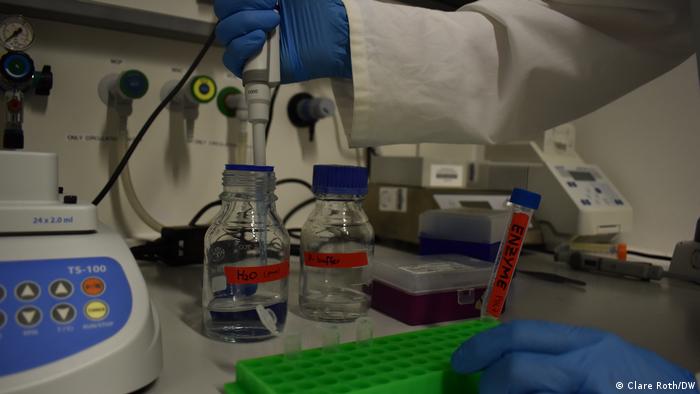

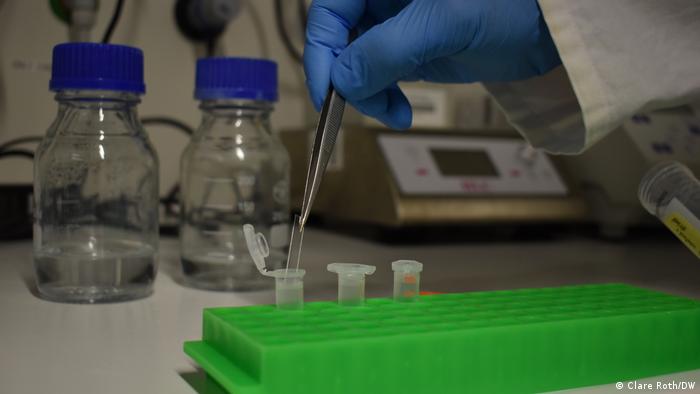

Plastics are now found in oceans, rivers, lakes, air, ice and soil. Scientists have identified tiny pieces of plastics in the human digestive system, blood stream, lungs and even the placenta. While we do not fully understand the impacts of this exposure, these findings are highly concerning. Chemical additives used in plastics include BPA, flame retardants, phthalates and thousands of other chemicals, many of which are toxic and have been linked to cancer, infertility, brain damage and other serious human health conditions.

Plastics and chemicals have already altered vital Earth’s system processes to an extent that exceeds the threshold under which humanity can safely develop and thrive in the future. Plastics contain tens of thousands of chemical additives, as well as non-intentionally added substances. It’s impossible to ensure the safety of this large variety of substances, mixed in a myriad of different ways.

Plastic’s climate change impacts

The life cycle of plastic also has serious climate impacts. It accounts for 4.5% of the annual greenhouse gas emissions and could consume 10% to 13% of our remaining carbon dioxide budget by 2050. This is in part because single-use plastics are heavily produced in countries dependent on coal.

As the world shifts to renewable energy sources, the fossil fuel industry is looking to increase plastics production. Plastic producers have been expanding their capacities by up to 40%, with $180 billion invested in fracking (which produces ethylene, a critical ingredient in various plastics), and in plastic production.

There are many other, yet largely unexplored ways in which plastics could impact the Earth’s system. They could affect the amount of sunlight reflected back to space in the Arctic. Or they could change the carbon dioxide sequestration by phytoplankton and the marine carbon pump, which is part of the ocean carbon cycle responsible for cycling of organic matter formed by phytoplankton during photosynthesis. Plastics could also alter essential nutrient cycling functions of soils on land.

“Wish cycling”

It is clear that we need to reduce plastics now. We cannot afford to become yet more dependent on historically flawed and insufficient strategies of downstream waste management.

Even high-income countries are ill-equipped to keep pace with the growing amount of waste. Recycling is often just “wish-cycling,” as environmental sociologist Rebecca Altman puts it. Recycling rates are as low as 5% in the United States and average only 9% globally.

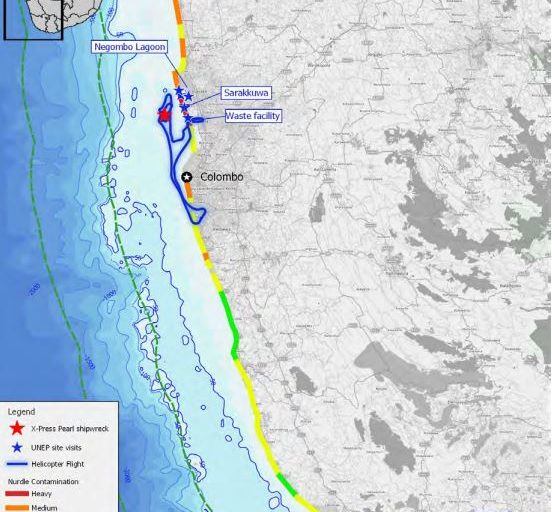

Sometimes recycling is simply a global redistribution of waste. Millions of tons of plastic waste are still exported from the Global North to the Global South. The toxic waste of these exports frequently ends up disposed of by vulnerable communities, who carry the burden of pollution. Scholars have identified this as a form of colonialism.

The idea of a circular economy hasn’t worked in practice and would be difficult to implement on the large scale needed. Yet the steep increase in plastic production isn’t challenged enough. As a result, more and more plastics and toxic compounds are leaking into all corners of the environment and into our bodies.

Unfortunately, this isn’t a mess we can clean up later. Breaking down into micro and nanoparticles, it’s a form of pollution that is irretrievable and irreversible. Trying to sift it up is a Sisyphean task that might endanger crucial ecosystems, such as the neuston – tiny organisms floating with ocean currents to areas where plastic waste accumulates.

Phasing out virgin plastics

Recycling rates are as low as 5% in the United States and average only 9% globally. (Credit: Lisa Risager/flickr)

Even when applying all political and technological solutions available today — including substitution, improved recycling, waste management and circularity — annual plastic emissions to the environment can only be cut by 79% over 20 years, a study of scenarios in the journal Science found. It also suggests that, even with these actions, after 2040 17.3 million tons of plastic waste will still be released to the environment yearly. The path forward must include a phase-out of virgin plastic production by 2040.

In calling for a production cap, we do not discount the benefits that plastics present in healthcare or transportation. We are mindful of the possibilities that plastics engender in low-income countries or for disability communities. We do not envision a future without plastics, but one with much less of it, just for the applications that are necessary or vital for vulnerable populations. For all remaining plastics we need a robust circular economy that regulates toxic plastic chemicals as well, keeping them out of the loop to ensure human and environmental safety. A reduced production of new plastics would likely boost the value of recycled feedstock, incentivizing recycling. If justly regulated, this would secure socioeconomic benefits and operational safety for millions of workers across the world, who draw a living removing and renewing plastic waste.

The new plastic treaty could create opportunities for innovation in technology, society, science and policy-making — bringing together citizens, scientists, industry and governments alike. We hope that it will be strong, binding and creative, bravely tackling the true roots of the issue.

This article is a collaborative work of the authors together, find their bios here.

Banner photo: Celebrating the UN resolution on plastic, which passed in March 2022. (Credit: UNEP)

From Your Site Articles

Related Articles Around the Web