German consumers religiously return their bottles under the bottle deposit scheme. But how exactly does it work? And is it a model other countries could follow?

It’s Saturday morning and people are queuing with bags full of bottles and cans at a supermarket in the German city of Cologne. But they’re not buying. Instead, they are returning them.

The process is easy. When they bought their drinks, the shoppers paid a deposit on top of the cost of the beverage itself — the so-called Pfand. When they return their bottles and cans to the store, they get their money back.

“Before 2003, some 3 billion disposable beverage containers were dumped in the environment every year,” Thomas Fischer, head of circular economy at NGO Environmental Action Germany (DUH), told DW.

These days, the country boasts a returns rate of above 98%. “It’s impossible to reach a higher rate,” Fischer said.

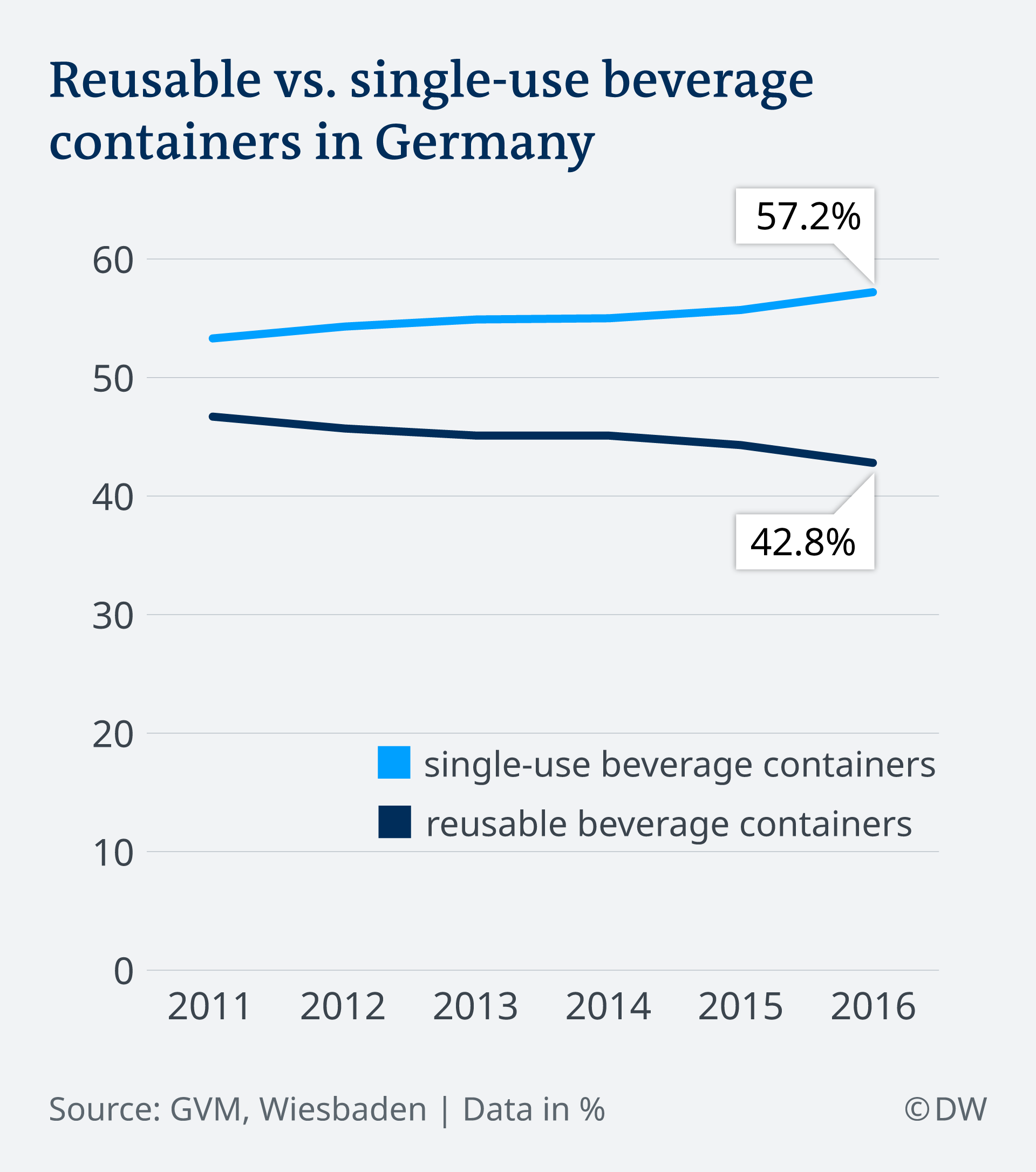

There are two types of bottles in Germany’s Pfand system. The first, which have producer-set deposit prices ranging from €0.08 to €0.25 ($0.29), can be reused multiple times and can be made from glass or PET plastic. The second are single-use containers, which as the name suggests, are only used once before they’re recycled. On these, the deposit price is fixed by the government at €0.25.

Though for consumers, the Pfand system is a simple case of putting empties into a machine, what happens thereafter is a bit more complex.

Adventurous bottles

When a refillable bottle of, say, cola, is returned to the supermarket, it marks the start of a long journey.

A drinks wholesaler transports it to a sorting facility with a truckload of empties, where it is put with other bottles of the same shape before being taken to a producer that uses that particular type of bottle. There, it is cleaned, refilled and delivered back to a shop shelf for repurchase.

Such a glass bottle can be refilled up to 50 times without losing quality, the state-run German Environment Agency (UBA) says. For reusable plastic bottles, it puts the re-use rate at 25.

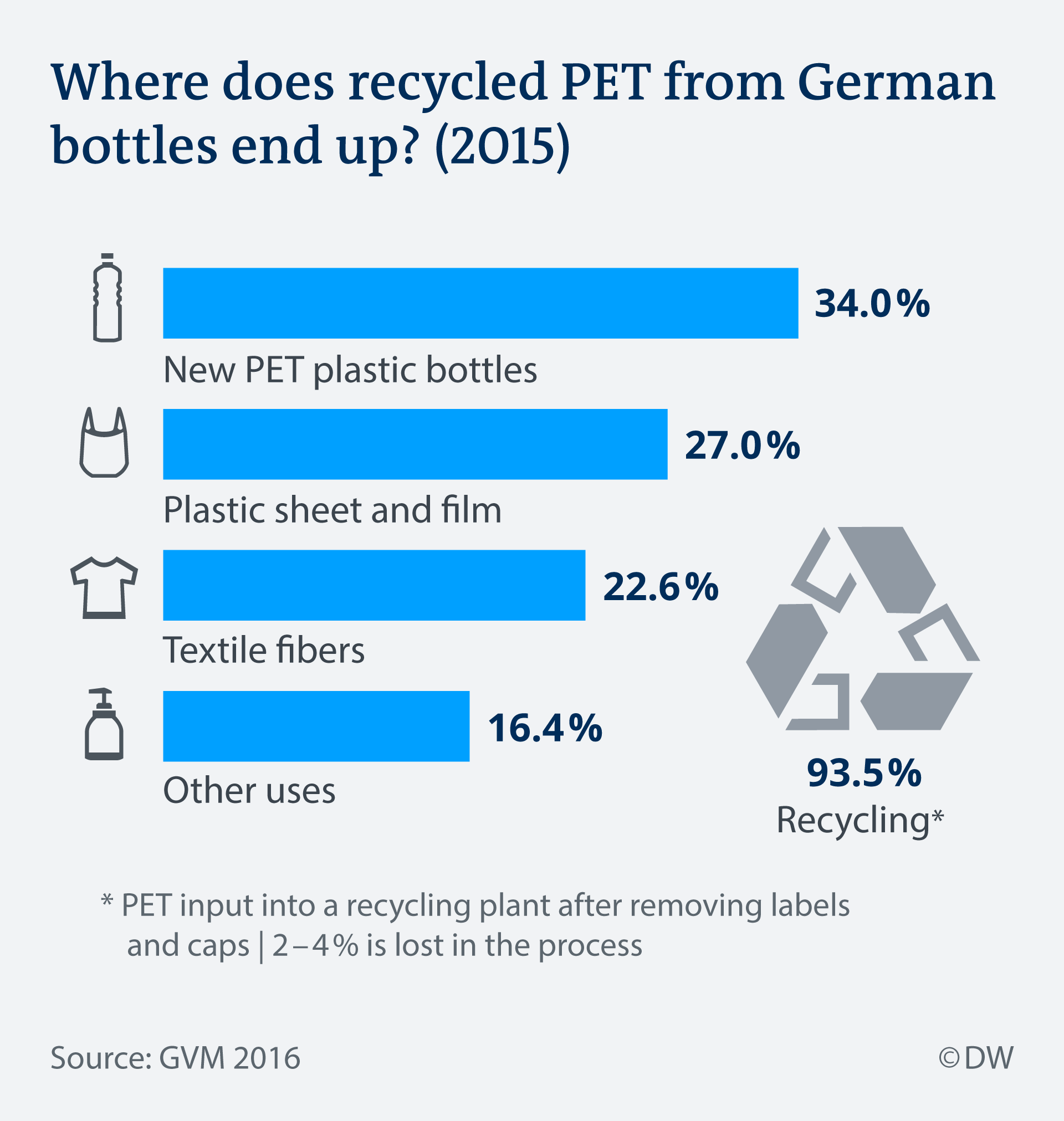

Single-use bottles follow a different path. Once they’ve been collected in-store, they’re packed off to a recycling plant, where they’re shredded and turned into pellets to be made into new plastic bottles, textiles or other plastic objects, such as detergent containers.

Which option is better for the environment?

The deposit system for both reusable and single-use bottles saves raw materials, energy and CO2 emissions — mainly because it reduces the fossil fuels used to produce new bottles, Gerhard Kotschik, packaging expert with UBA, told DW.

And recycling single-use bottles — as opposed to a sack of mixed plastics — results in food-grade material. On this basis, discount supermarkets, such as Aldi and Lidl, mostly sell single-use containers, claiming their recycling activities are good for the environment.

“Compared to the situation a few years ago, we use up to 70% less virgin PET material,” a Lidl spokesperson told DW.

This, however, has led to the growing popularity of single-use items. “If we want to be competitive, we have to offer our drinks in discount stores,” Uwe Kleinert, head of sustainability at Coca-Cola Germany, told DW.

Coca-Cola’s use of reusable bottles slipped from 56% to 42% in 2015, according to figures from the DUH. The company joins PepsiCo as one of the world’s biggest plastic polluters, found Break Free from Plastic, a coalition of NGOs working to reduce plastic waste. In Germany, however, many of Coca-Cola’s beverages do appear in reusable plastic bottles, and some in glass.

The Schwarz Group, to which the discounter Lidl belongs, now produces single-use bottles for its own products. According to the company, it uses recycled PET. Only the labels and the lid are not made of 100% recycled plastic, they say.

Nevertheless, environmentalists say that reusable bottles are generally more environmentally friendly than single-use packaging. According to the DUH, single-use plastic bottles made from 100% recycled material still only make up a small share of the market. In addition, material is lost in every recycling process, according to the DUH. There is no closed loop whereby material can be converted into a new product indefinitely without losing any of its properties.

Production of most of these bottles also still requires raw materials derived from fossil fuels. “On average, single-use PET bottles in Germany contain 26% of recycled material,” Fischer said.

In addition, reusable plastic bottles are also shredded into reusable PET granules, said Gerhard Kotschik of the UBA. This happens when a bottle has reached its refill quota, i.e. when it can no longer be reused in its original form.

“We always recommend buying reusable beverage containers from the region,” Kotschik told DW, adding that recycling only becomes the best option once a bottle has reached its refill quota. “Even better, however, is to avoid waste altogether.”

Confusion over labeling

Unlike for single-use bottles, there is no mandatory uniform symbol for reusable bottles and labeling may vary to include terms like “returnable bottle,” “deposit bottle,” “returnable” or “reusable bottle.”

Retailers must mark whether bottles are single or multi-use on their store shelves, but for a shop or supermarket selling only single-use bottles, one sign in-store is enough. Environmental organizations such as the German NGO Nature and Biodiversity Conservation Union (NABU) criticize this as insufficient.

Deposit systems’ infrastructure, particularly for reusable bottles, makes its introduction challenging

While most consumers in Germany now recognize whether a bottle is single or multi-use, 42% of people still think that all deposit bottles — including single-use bottles — are refilled, according to a recent survey.

Who benefits from the deposit-return system?

Stores that only sell single-use bottles avoid the logistic costs connected to reusables and they also benefit from the recycling and onward sale of high-grade PET.

“You have to pay more for recycled PET than for virgin PET made from oil,” Kleinert said, but it’s key to achieving environmental targets.

The business is becoming so lucrative that Lidl has even set up its own recycling group. Fischer said “every bottle is a gift” for discount stores.

Even unreturned empties — both refillable and single-use — spell profits for the stores that sold them. With 16.4 billion single-use bottles flooding the German drinks market every year, the 1.5% that are never taken back can translate into profits of as much as €180 million for retailers.

A model for other countries?

German state environment agency UBA said there is no silver bullet for all countries and that each context has to be closely evaluated to decide what works best. But big companies that have long opposed the introduction of deposit systems are beginning to change their position.

“We support well-designed, industry-owned deposit return schemes across Europe where no proven successful alternatives exist,” Wouter Vermeulen, senior director of Coca-Cola public policy center for Europe, told DW in an email.

Cesar Sanchez, a spokesperson for Retorna, a Spanish NGO pushing for bottle deposit schemes, believes this is a response to social pressure and stricter European legislation on single-use plastic — by 2029, 90% of plastic bottles must be collected separately for recycling.

“Society is demanding solutions and I think deposit return schemes will soon arrive in Spain and all other countries,” he said.

Even in Germany, environmental groups are pushing for the deposit scheme to be rolled out to include all kinds of glass and carton packaging, such as Tetra Paks.

“It would also be possible to develop these containers for jam or honey,” Fischer said. “All products can be reusable, and that’s what we want.”

Edited by: Tamsin Walker and Jennifer Collins