Share this articleMuzaffarnagar, a city about 80 miles north of New Delhi, is famous in India for two things: colonial-era freedom fighters who helped drive out the British and the production of jaggery, a cane sugar product boiled into goo at some 1,500 small sugar mills in the area. Less likely to feature in tourism guides is Muzaffarnagar’s new status as the final destination for tons of supposedly recycled American plastic.On a November afternoon, mosquitoes swarmed above plastic trash piled 6 feet high off one of the city’s main roads. A few children picked through the mounds, looking for discarded toys while unmasked waste pickers sifted for metal cans or intact plastic bottles that could be sold. Although much of it was sodden or shredded, labels hinted at how far these items had traveled: Kirkland-brand almonds from Costco, Nestlé’s Purina-brand dog food containers, the wrapping for Trader Joe’s mangoes. Most ubiquitous of all were Amazon.com shipping envelopes thrown out by US and Canadian consumers some 7,000 miles away. An up-close look at the piles also turned up countless examples of the three arrows that form the recycling logo, while some plastic packages had messages such as “Recycle Me” written across them.Waste pickers in Muzaffarnagar sift through mounds of plastic trash for metal cans or or intact plastic bottles that could be sold, while children look for discarded toys. Photographer: Prashanth Vishwanathan/BloombergPlastic that enters the recycling system in North America isn’t supposed to end up in India, which has since 2019 banned almost all imports of plastic waste. So how did Muzaffarnagar become a dumping ground for foreign plastic? To answer that question, Bloomberg Green retraced a trail back from the industrial belt of northern India, through the brokers who ship refuse around the world, to the municipal waste companies in the US that look for takers of their lowest-value recycling. Finally, the search arrived at the point of origin: American consumers who thought — wrongly, as it turns out — that they were recycling their trash. It’s a system that’s supposed to cut pollution, spare landfills and give valuable materials a second life. But in Muzaffarnagar the failures are hard to miss. The region’s other major industry is paper production, with more than 30 mills dotted among the furnaces for making jaggery. Paper factories in India often rely on imported waste paper, which is cheaper than wood pulp. The nation’s paper makers need to import around 6 million tons annually to meet demand, and most of it comes from North America. This could be a recycling success story — were it not for all the plastic that comes mixed into all the waste paper. Exported paper recycling typically includes loose sheets from offices, old magazines and junk mail. But the bales are frequently contaminated with all kinds of plastic that consumers have tossed into their recycling bins, including the flimsy wrapping that holds water bottles together in a pack, soft food packaging and shipping envelopes. Most ubiquitous of all discarded plastics at the illegal dump sites were Amazon.com shipping envelopes thrown out by US and Canadian consumers some 7,000 miles away. Photographer: Prashanth Vishwanathan/BloombergDemand for paper has created an unaccountably large loophole in the ban on plastic waste from overseas. India may be bringing in as much as 500,000 tons of plastic waste hidden within paper shipments annually, according to a government environmental body that estimated the level of contamination at 5%. While the government allows up to 2% contamination in recycled paper, lax enforcement at ports means no one’s checking. So there’s no way to measure how contaminated the bales really are. Plastic contamination also comes through in recycled paper shipments sent from North America to other Asian countries, where dirty diapers, hazardous waste and batteries have all turned up. The amount of plastic trash coming into India in waste paper now is almost double the 264,000 metric tons that was legally imported in 2019 to the country before it imposed the ban in August of that year, according to figures from the United Nations Comtrade database. Since the ban, the government has allowed a small number of companies to import recyclable water bottles. Under the Basel Convention, a UN treaty that regulates international flows of hazardous waste, exporters of plastic are also required to obtain explicit consent from importing countries before shipments are sent.Perhaps one reason why the system is failing in India is that there are end users for plastic that mostly can’t be recycled. “There’s value in all plastics,” says Pankaj Aggarwal, the managing director of a local paper mill and chairman of the Paper Manufacturers Association for the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh. “There are people who will buy it and have use for it.” Pankaj Aggarwal operates Bindlas Duplux Ltd., a paper mill that sends plastic that comes with imported waste paper to a cement plant for incineration Photographer: Prashanth Vishwanathan/BloombergStill, Aggarwal says, he isn’t in the recycling business. That’s why he sends the unwanted plastic that comes through with the imported waste paper by tractor to a cement factory more than 400 miles away, where it ends up incinerated for energy. It’s a legal method of disposal in India. Other countries allow it too, though typically impose strict environmental standards. Cement kilns are hot enough to completely consume plastic, though the process is hardly climate positive. The greenhouse gas emissions from burning plastic are about the same as burning oil.Most of Muzaffarnagar’s paper mills have workers do a first-pass sift for the most valuable plastics such as water bottles, which can be recycled. The rest is carted off by unlicensed contractors who dump it at illegal sites throughout the city. There, it will be further sorted by laborers who are paid about $3 a day for potentially recyclable materials and dried out. The bulk is resold to paper and sugar mills to burn as fuel. The heat in boilers and furnaces at paper and sugar mills do not generate enough heat, however, so microplastic ash from the unconsumed remnant perpetually falls across the city. The mills also aren’t equipped with sufficient filtration to capture toxic emissions, equipment that can cost millions of dollars. In October alone, the Uttar Pradesh Pollution Control Board fined nearly half of the mills in the city for burning plastic, improperly disposing of the waste and failing to manage the ash.“So much of the plastic waste from abroad has no saleable value, and it can’t be recycled,” says Ankit Singh, regional officer for the Uttar Pradesh Pollution Control Board. “It’s just being dumped here and then will get burnt.”The long journey taken by most of the plastic that reaches Muzaffarnagar is difficult to trace, even when branding indicates a North American origin. But every so often an identifying mark provides a clear starting location. One plastic envelope with a United States Postal Service label stood out from the piles at a local dump site because it still had a name and address printed directly on it. The parcel had been shipped to Laurie Smyla, a 73-year-old retiree from Sloatsburg, New York. There was no doubt in her mind: Smyla had put that envelope into her recycling bin. “That’s polyethelene, and I’d recycle that. If it’s got the recycling symbol on it, into the bin it goes,” she says. “I get a lot of Amazon packages, and they all go into the bin, too.” Smyla has a degree in environmental science and even served as coordinator for the local recycling program in the late 1980s, as she explains when reached by phone. She was able to quickly identify the envelope as polyethylene, the most common type of plastic. It arrived in September with prescription medication. Most consumers like Smyla have been lulled into thinking that the three-chasing arrows, a marketing symbol created by the petrochemical industry, found on many packages means it’s recyclable. In fact, it simply indicates which type of plastic it is. She was dismayed to learn that the plastic packaging she put into her recycling bin had traveled thousands of miles to pollute someone else’s backyard. “That is really a shame, considering that that stuff is not biodegradable and is going to last a millennium,” Smyla says. “I feel sorry for anyone who lives within a 5-mile radius of the site you’re standing on.”That would include Bobinder Kumar, a 35-year-old mechanic who lives with his wife and three kids in a bare two-room home. The plastic dump that had the envelope addressed to Smyla is just a few hundred feet from his home. Nearly every inch of the 3-acre site is strewn with trash. “We can’t escape the smell of the trash, even in our home,” he says. “It’s very terrible to live close to the site, but what can we do?”A paper mill’s smokestack in Muzaffarnagar spews black smoke, which experts say is the result of incomplete combustion that often leaves particles in the air. The area’s pollution control agency says black smoke is one indication that plastic may be burning. Photographer: Prashanth Vishwanathan/BloombergAnti-smog guns spray water on busy roads in Muzaffarnagar to settle pollution particles from the air. Photographer: Prashanth Vishwanathan/BloombergBy far the most common logo in the heaps just outside the Kumar home is the curved line and arrow of Amazon.com Inc. The blue-and-white plastic shipping envelopes favored for small parcels by the online retail giant were easy to spot on visits to six illegal dump sites in Muzaffarnagar. The logo was evident in piles of plastic waiting to be burned at several sugar mills. The charred, half-melted remains of an Amazon envelope could be picked out from fly ash at a dump used by a local paper mill.Amazon wouldn’t comment on the presence of its packaging in Muzaffarnagar. The company “is committed to minimizing waste and helping our customers recycle their packaging,” a spokesperson said in a statement. “Since 2015, we have invested in materials, processes, and technologies that have reduced per-shipment packaging weight by 38% and eliminated over 1.5 million tons of packaging material.”Amazon generated 709 million pounds of plastic packaging waste in 2021 from all sales through Amazon’s e-commerce platforms globally, according to a report by international environmental group Oceana, up 18% from the prior year. At that volume the company’s air pillows to protect packages alone could circle the Earth more than 800 times. In a December blog post, Amazon said it reduced average plastic packaging weight per shipment by over 7% in 2021, resulting in 97,222 metric tons of single-use plastic being used across Amazon-owned and operated global fulfillment centers to ship orders to customers.Amazon delivery packages tout the company’s commitment to sustainability. Photographer: Prashanth Vishwanathan/BloombergAmazon’s bubble-lined plastic bags carry the recycling logo that’s often criticized for confusing consumers into thinking its packaging is easily recycled. Soft plastics used in bags and wrappers are some of the hardest and least economically viable materials to recycle. Most American recyclers can’t process them.Closer inspection of Amazon’s envelopes shows “Store Drop-off” printed with a link to How2Recycle, a third-party organization that offers educational material on recycling. Users who want a list of drop-off locations are directed to another website for locations that accept plastic items with the Store Drop-off logo, including big-box retailers such as Safeway, Target and Kohl’s. Amazon said it doesn’t control the management of plastics waste once it’s dropped-off by customers.By the time plastic parcels arrive in India, though, there’s no question of reusing the material for anything other than fuel. Jaggery is a cane sugar product boiled into goo at some 1,500 small sugar mills in the area. Photographer: Prashanth Vishwanathan/BloombergIt’s been routine practice for Mohammad Shahzad, a sugar mill owner in Muzaffarnagar, to burn bagasse — dry sugarcane pulp — mixed with plastic scrap to fuel his furnace. Next to Shahzad’s furnace sits a large pile of bagasse mixed in with bits of plastic packaging to go into the fire, including an Amazon package envelope, Capri Sun drink pouch and the outer layer of plastic that held together a 12-pack of bottles of Kirkland-brand juice drinks.The remnants of sugarcane aren’t quite combustible enough for the process, and wood is expensive. Mixing in plastic economizes the operation. “Plastic heats up the sugar well,” says Shazad, whose crew of six works while a group of children run about. “We make very little money.” He says other sugar mill owners use the same approach. Shahzad’s mill sits off a stretch of road lined with sugarcane fields and operations that are practically open-air except for a thatched roof. Such mills are rudimentary: sugarcane is fed by hand into a machine that squeezes juice from it, leaving behind pulpy remnants that will be dried and later on burned as fuel to boil the juice down to what will become raw sugar when cooled. Sugar mills in Muzaffarnagar burn bagasse — dry sugarcane pulp mixed with plastic scrap — to fuel their furnaces. The remnants of sugarcane aren’t quite combustible enough alone for the process, and wood is expensive. Photographer: Prashanth Vishwanathan/BloombergIn the villages around the sugar and paper mills, residents say they usually know when plastic has been burnt overnight because they wake up to a layer of ash that coats terraces, crops and anything left outdoors. Burning plastic releases a slew of toxins into the air, including dioxins, furans, mercury and other emissions that threaten the health of people, animals and vegetation, according to multiple studies. Exposure to burning plastic can disrupt neurodevelopment as well endocrine and reproductive functions, according to the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences in the US. Other chemicals emitted in burns, including benzopyrene and polyaromatic hydrocarbons, have been linked to cancer.The burns, along with other industrial pollution, leave a thick gray-yellow smog over Muzaffarnagar that rarely lifts. On most days the air-quality index in the city is above 175 — or “unhealthy” — and there are often warnings to limit exposure outside. Around Muzaffarnagar, respiratory problems such as asthma and bronchitis along with eye infections associated with air pollution and the burning of plastic are on the rise, up as much as 30% over the last few years, according to Muzaffarnagar’s chief medical officer. District officials have started visiting factories overnight to identify culprits and fine them. But it isn’t enough to clear the air. In the villages around the sugar and paper mills, residents say they usually know when plastic has been burnt overnight because they wake up to a layer of ash that coats terraces, crops and anything left outdoors. Photographer: Prashanth Vishwanathan/BloombergParmanand Jha makes surprise inspections of paper mills suspected of burning plastic and shuts them down on the spot. The subdivisional magistrate in charge of Muzaffarnagar city has disconnected conveyor belts and chutes that sent plastic into the boilers at several paper mills this year. He knows his interventions are not a real deterrent. “They can save money burning plastic,” he says, “even with the fines.”The furnace operators of Muzaffarnagar have found a way to profit from a waste stream that municipal collectors thousands of miles away see as valueless. The broken pathway that takes would-be recycled plastic from a town in New York to the furnaces of India first passes through a county recycling program that — understandably — doesn’t want to deal with plastic envelopes and packaging trash. District official Parmanand Jha has caught paper mills burning plastic in the middle of the night and shut them down. Photographer: Prashanth Vishwanathan/BloombergThe sorting center that took in Smyla’s envelope and other discarded materials for recycling from the homes in Sloatsburg doesn’t take soft plastics because it wraps around the sorting machines and snarls them up. Soft plastics “constitute contamination because of what it does to the equipment,” says Gerard M. Damiani Jr., executive director for Rockland County Solid Waste Management Authority, which handles waste for 332,000 residents, including Smyla. “They’re not acceptable items in our program.” Most recycling centers in the US won’t accept soft plastic.Damiani says consumer packaging and bags are the responsibility of retailers who sell the products. Under New York state law, retailers are required to offer store drop-off points for consumers to bring back and recycle soft plastics and shopping bags. He says the county isn’t responsible for handling the retailers’ recycling bins, and he has no idea what happens to those items once they’re dropped off.Just because most consumer packaging waste isn’t eligible doesn’t mean that it stays out of the system. It’s possible Smyla’s envelope got mixed up with a paper load collected by the county, which has a contract with a New Jersey-based company called Interstate Waste Services to handle recycling. It’s also likely the plastic pouch was sorted at the recycling facility and accidentally sent into the paper stream. According to Damiani, the Interstate representative who handles Rockland’s waste told him it does export some paper recycling overseas.Interstate’s facility in Airmont, New York, recycles commingled paper of all grades from Rockland County and lists N&V International and N&V Syracuse as the destination for most of its recycled paper waste in 2020, according to an annual report filed to New York’s Department of Environmental Conservation. It was not possible to confirm the chain of custody for Smyla’s shipping envelope, and N&V didn’t respond to requests for comment.Rockland’s contract with Interstate doesn’t preclude sending materials overseas, but Damiani is against it. “You should deal with your own waste within your own borders,” he says. Bloomberg Green contacted several Interstate executives to ask how plastic waste from suburban New York could have ended up dumped in a field in India. None responded. Officials have started visiting factories overnight to identify culprits and fine them. But it isn’t enough to clear the air. Photographer: Prashanth Vishwanathan/Bloomberg The movement of waste from rich countries to poorer ones with laxer enforcement tends to be facilitated by brokers, who either charge a fee to dispose of unwanted material or buy it cheaply and sell it overseas. The Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime has called brokers “key offenders” in the black-market waste trade, with links to major fraud and criminal gangs.The trade in residential waste paper is volatile, with aggregate prices for mixed paper dropping to zero in the last two months, compared to $80 a ton this time last year. Most brokers are giving it away, with importers paying just the shipping cost, says Bill Moore, president and owner of Moore & Associates, a paper industry consultant in Atlanta. That translates into meager incentives for recycling centers and brokers to make sure that plastic contamination in bales of recycled paper is low and meets India’s little-enforced legal threshold. At many older facilities in the US, residential recyclables that get mixed together at collection are sorted into glass, metal and plastic. Paper, magazines and mailers are weeded out for recycling. But flat plastic packaging and shipping envelopes can easily pass as paper.“Shipping envelopes and thinner plastic materials act like paper, and it floats into the paper stream,” says Moore. “It’s exactly the type of plastic that will be contamination in a paper bale and get shipped to India.”Residue ash containing semi-burnt plastic bags from a steam boiler of a paper mill arrives at a scrap yard in Muzaffarnagar. Photographer: Prashanth Vishwanathan/BloombergSmyla felt manipulated to find her carefully sorted waste had joined the mountains of trash at Muzaffarnagar. “I feel betrayed as a consumer,” she says. “That recycling symbol — it’s all a marketing feel-good message and very deceptive. It should not be harming other people in other parts of the world.”For Kumar, the mechanic living beside heaps of North American plastic waiting to burn, those good intentions can’t blunt the harm that’s an everyday fact of his life. “My kids and the neighbors all have allergies and breathing problems,” he says. “I worry about diseases.”—With assistance from Leslie Kaufman and Manoj KumarThe visual media in this project was produced in partnership with Outrider Foundation.More On Bloomberg

Category Archives: Land

Countries resolve to protect cetaceans from marine plastic pollution

Following the adoption of a Resolution on Marine Plastic Pollution at the 68th International Whaling Commission conference (IWC68) in October, member countries will have to report on the status, reduction, recycling, and reuse efforts on marine plastic pollution.At IWC68, member nations adopted a resolution to support international negotiations on a treaty to tackle plastic pollution. The body also recognised the transboundary nature of marine plastic pollution and the importance of international cooperation.The Resolution on Marine Plastic Pollution commended the UN Environment Assembly’s March 2022 decision to begin negotiations on an international legally binding instrument to tackle plastic pollution, including in the marine environment.For India, local communities will be crucial stakeholders in tackling ocean plastic, say biologists. At the 68th International Whaling Commission conference (IWC68) in Slovenia in October, member nations adopted a resolution to support international negotiations on a treaty to tackle plastic pollution. Countries will now aim to report on the status of marine plastic debris. For India, local communities will be crucial stakeholders in tackling ocean plastic.

The International Whaling Commission (IWC) is an inter-governmental body responsible for the management of whaling and the conservation of whales.

It has a current membership of 88 governments from all over the world, including India, which played a critical role in amending the text of the resolution to incorporate reporting commitments on the status of marine plastic by member countries.

Confirming that the impacts of marine plastic pollution on cetaceans is a “priority concern” for the IWC, the Resolution on Marine Plastic Pollution adopted at IWC68, commended the UN Environment Assembly’s March 2022 decision to begin negotiations on an international legally binding instrument to tackle plastic pollution, including in the marine environment.

Though the IWC’s main focus is to keep a check on whale stocks and ensure there is a balance in the whaling industry, it is also concerned with plastics and marine debris because they impact the survival of whales, dolphins, and porpoises, among other marine species.

Plastic ingestion and entanglement in nets are the other issues that lead to injury and death of such marine animals. Welcoming the IWC68 resolution, Sajan John, a marine biologist at Wildlife Trust of India, says, “Since whales and whale sharks are filter feeder animals, they clean the water. When they ingest plastic, it could get into their digestive system and create many issues.”

The International Whaling Commission conference (IWC68) was held in Slovenia in October 2022. Photo by Sharada Balasubramanian/Mongabay.

The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) estimates that almost 13 million tonnes of plastic enter the oceans yearly, affecting approximately 68% of cetacean species. Plastic ingestion cases are found in at least 57 out of the 90 known cetacean species (63.3%). Ingestion of plastic has been recorded in all marine turtle species and nearly half of all surveyed seabird and marine mammal species. Apart from this, those species that are not directly impacted by ingestion or entanglement could suffer from secondary impacts such as malnutrition, restricted mobility and reduced reproduction or growth, experts at the conference shared.

This resolution, with amendments from India, was one of the major successes at the IWC meeting. The draft Resolution on Marine Plastic Pollution was proposed by the Czech Republic on behalf of the European Union member states parties to the International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling; the resolution was co-sponsored by the United States of America, the United Kingdom, the Republic of Korea, Republic of Panama and India.

Following the adoption of the resolution, India, at the IWC68, shared that in 2019, “20.34 million tonnes of plastic was generated in India, and 60% of the same were recycled against the world average of 20%. So the solid waste management capacity in India, which was only 18% in 2014, increased to 70% in 2021. The Bureau of Indian standards classifies microbeads in cosmetics as unsafe and has banned microbeads in cosmetics. This was implemented in 2020 along with the ban on importing plastic waste.”

At the discussion on the resolution of the IWC meeting, Bivash Ranjan, Additional Director General of Forests at India’s Ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change (MoEFCC), who was with the country delegation at the meeting, said that one of the early threats India perceived for the marine aqua fauna was plastics.

Ranjan said, “Apart from banning single-use plastic and microbeads, India has also taken steps to clean the coasts and make them plastic-free.” He said that this move (removing all the plastic litter across coasts) will further strengthen the conservation plan of the dolphins.”

Actions post-resolution

In the follow-up to the IWC resolution, the next step is for countries to report on marine plastic waste.

India made an amendment to the resolution asking member countries to report on the status of marine debris around their country and the amount of plastic recycling and usage.

On the implications of the IWC68 resolution to the conservation of cetaceans and whales, Vishnupriya Kolipakkam, Scientist, Wildlife Institute of India (WII) said, “This will help us to identify where and what the problem is. Otherwise, it’s just a resolution that says, let us reduce the use of plastic. The member countries will take the route of sustainable use and reduce single-use plastic. It has a broad general resolution, and many countries are already doing this. But because of India’s intervention, we suggested that member countries have to report back on the status and recycling usage of plastic. Now, it would be more relevant because we can call on people and governments who are not actively doing anything,” she said.

Challenges and solutions for implementation

However, the success of implementing the IWC68 resolution will depend on many factors. In India, a tropical country, plastic pollution does not emerge from a single point source, points John. Many tributaries of rivers drain into the ocean. Many human activities are localised in the rivers’ upstream, and plastics dumped into the rivers eventually end up in the oceans.

John told Mongabay-India, “Most of the time when we talk about marine plastic pollution, it is about removal from the coastal beach and clean up activities. Everything is centered around the coastal area. We are trying to address the issue on the periphery, but we are not trying to address the issues from the upstream. Not much occurs upstream, and there is little awareness or action.”

He pointed out that complete tracking of plastic and collecting the data is beyond quantifiable. “One, we are on the tropical side of the oceans; two, we depend heavily on disposable plastic, so quantifying that would be challenging,” John added.

Disposable plastic has contributed to the marine debris in the ocean, which affects the marine organisms. Photo by Hajj0 ms/Wikimedia Commons.

Local communities will be crucial to the IWC68 resolution’s implementation.

At WTI, John has been looking at different approaches to tackling India’s marine plastic pollution problem. He works with the fisher community, telling them to bring back marine debris found in the ocean. Involving local fishing communities that go to the sea daily is one way to remove plastics from the ocean effectively.

“India has a coastline spanning 8,000 kilometres, and fisher families have almost tripled. If we mobilise them on the east coast, west coast, and the two of our island territories, we can recover plastic,” said John.

The major issues in Indian coasts are bottles, polythene bags, plastic wrappers, and covers. The nets contribute to a small part of the debris, he added.

Also, a complete ban on plastic will be tough. John says, “We have moved from biodegradable to plastics, so everything revolves around plastic now. Plastic use is high in the medical industry, especially during the pandemic. Polymer science has also advanced. If there is an alternative to single-use plastic, those could be given at a subsidised rate. But if the price of the alternative product is high, then people would opt for the cheaper plastic.”

IWC’s initiative on marine plastics

Almost two decades ago, the IWC recognised the significance of marine debris impacts on cetaceans. Plastic pollution spans five of the eight priority areas of environmental concern identified by the IWC’s scientific committee. This was endorsed by the commission in IWC Resolution 1997. In addition, Sustainable Development Goal 14 (SDG 14) aims to conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources, including preventing and reducing marine pollution of all kinds by 2025.

Within the framework of IWC, there was another crucial resolution in 2018 on ghost gear entanglement in cetaceans. The Commission has encouraged the conservation committee, scientific committee, and whale killing methods and welfare issues working group to consider engaging organisations on marking the gears used for fishing so that the net entanglement issues could be examined.

Marine debris like ghost nets continue to pose a threat to marine wildlife. Photo by Tim Sheerman/Wikimedia Commons.

In the IWC68 resolution, the body also recognised the transboundary nature of marine plastic pollution and the importance of international cooperation by IWC’s contracting governments and other international organisations, including the UN Environment Programme (UNEP), Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), Convention on Migratory Species (CMS), Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), Arctic Council and International Maritime Organisation (IMO).

As a result, the IWC secretariat was directed to look at ways in which they can engage as a stakeholder within the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC) process.

It was recommended that the contracting countries submit reports, voluntarily, to the scientific progress committees on the status, reduction and recycling of plastic, and ingestion in stranded marine animals. The Commission, in the recent resolution, also recommended the IWC secretariat to add marine debris mapping along the Important Marine Mammal Areas (IMMAs). Further, there were also requests to reduce single-use plastics in the IWC day-to-day operations itself. All this will be discussed further in the next meeting, IWC 69.

[This story was produced with support from the Earth Journalism Network’s Biodiversity Media Initiative]

Read more: Unpacking the presence of microplastics in the Bay of Bengal

Banner Image: A humpback whale. Photo by Christopher Michel/Wikimedia Commons.

'There's no reason not to': More Nova Scotia lobster plants get on board with pollution control

If you walk along one of Nova Scotia’s many shorelines, you’ll see rocks, shells, and mounds of seaweed. But some of those beaches are also riddled with colourful rubber bands, ropes and fragments of plastic. According to Angela Riley, founder of Scotian Shores, a local business dedicated to cleaning the shorelines of the province, the province’s biggest industry is also behind much of the pollution found near the ocean. Many of the bands and plastics that end up on the beach are the byproducts of lobster fishing, storing and processing — the system that gets lobsters from the ocean onto people’s dinner plates around the world. “Yesterday we cleaned up 300 pounds of garbage, and today, in that exact same spot, there’s probably 10,000 bands in the seaweed,” Riley said. “Sometimes it feels like there’s millions. You pick up the seaweed and hundreds of them fall out. It’s insane.”Angela Riley holds bags full of lobster bands that she and her team collected during a beach cleanup.

Jennifer Jones: Why bother saving the planet?

It’s time to give up on saving the planet. Nature is screwed, so don’t bother caring about the environment. In the new year, put concern for clean air and water behind you and find other things to focus on.Or not. Maybe there are reasons to believe in caring for nature. Recently, leaders from more than 190 countries met in Montreal to safeguard biodiversity — the variety of life on this planet, from individual species to whole ecosystems. In the final hours of a two-week conference, they agreed to protect 30 percent of land and water by 2030. While the so-called 30×30 plan is not legally binding and the United States is famously not part of this, nor many other international environmental treaties, it’s an important step in the right direction.Global biodiversity is under immense threat as our impact on this planet grows. Our love of cheap burgers means we continue to chop down forests to farm more cows. Unsustainable fishing and pollution threaten our oceans. According to the World Economic Forum, for every pound of tuna we remove from the ocean we replace it with two pounds of plastic. And human-driven climate change has intensified droughts, floods and warmed ocean waters making it harder for plants, animals, and ecosystems to survive.While we used to think protecting nature was to save polar bears and pandas, we have come to understand that what’s good for wildlife is good for people. Conserving mangroves saves habitat for fish and manatees but also provides a storm buffer and job engine for our community.Only 17 percent of land and 8 percent of oceans is currently under some form of protection, so the 30×30 goal is ambitious, but not impossible.If you are a newcomer to Florida, it might be hard to fathom, but alligators almost went extinct just a few decades ago. Due to unregulated hunting and the trade in alligator hides, they were declared an endangered species in the 1960s. Through policy and enforcement, the alligator population recovered enough to be removed from endangered species status in the late 1980s. It was a similar story with Florida’s birds that were almost wiped out over a hundred years ago as their plumes were sought to adorn fashionable hats. The policies ultimately used to protect these birds served as a catalyst for Florida’s conservation movement. There was a time when Floridians did not know a future with Everglades National Park, Six Mile Cypress Slough Preserve or Lovers Key State Park. Now it’s impossible to imagine a future without them.These success stories illustrate that when confronted with the harsh reality of our behavior, we can choose to do better. This moment in time is different because the threats are bigger, necessitating a bigger and quicker response. It won’t be enough to simply remove hunting pressure on a few species when we are paving over entire ecosystems.To be sure, some will argue the needs of humans should always come before choices to benefit wetlands, wild grasses and coral reefs. But nature is our best insurance for the future. Biodiversity provides our air, food, water, medicines, jobs, recreation and so much more. It makes all of us safer in the face of climate change.A new year brings possibility and hope. Resolutions to do better. We can and should do more to protect all living things on this planet and ultimately ourselves.Jennifer Jones, Ph.D., is director of the Center for Environment & Society, part of The Water School at Florida Gulf Coast University.

Wind farm fears as SNP ministers admit they don't monitor 'toxic' leading edge erosion

A Scots Tory MSP has hit out after the SNP Government admitted it had no idea how many of Scotland’s 19,000 wind turbines may be releasing dangerous chemicals. There have been concerns for years about the environmental impact from the erosion of microplastics from the colossal turbine blades, which are made with fibreglass and epoxy …

2022’s top ocean news stories

Marine scientists from the University of California, Santa Barbara, share their list of the top 10 ocean news stories from 2022.Hopeful developments this past year include the launch of negotiations on the world’s first legally binding international treaty to curb plastic pollution, a multilateral agreement to ban harmful fisheries subsidies and a massive expansion of global shark protections.At the same time, the climate crises in the ocean continued to worsen, with a number of record-breaking marine heat waves and an accelerated thinning of ice sheets that could severely exacerbate sea level rise, underscoring the need for urgent ocean-climate actions.This post is a commentary. The views expressed are those of the authors, not necessarily Mongabay. 1. Negotiations for historic global plastics treaty break ground

Global leaders cheered to the strike of a recycled-plastic gavel in March, signifying a landmark decision by the United Nations Environment Assembly to create the first-ever legally binding international treaty to curb plastic pollution. With 8.3 billion metric tons of plastic having been produced to date, the decision marks a historic moment in addressing one of our blue planet’s greatest crises.

Negotiations for the global plastics treaty began in November in Uruguay, where representatives from more than 150 countries came together to start discussing details and goals. This International Negotiating Committee (INC) aims to finalize a formal treaty in a series of upcoming meetings by the end of 2024.

Without major efforts to reduce plastic pollution, projections show that 12 billion metric tons of plastic waste could end up in the natural environment or landfills by 2050. Plastic accounts for 85% of marine debris already, and the volume of plastic in the ocean may triple by 2040. Some groups are working to curb this pollution by capturing plastic waste in river mouths before it enters the sea. The Clean Currents Coalition, a global cleanup network facilitated by our team at the Benioff Ocean Science Laboratory at the University of California Santa Barbara, has collected nearly 1,000 metric tons of plastic from rivers in eight countries. However, it’s going to take more than a few trash wheels to solve the problem.

Recycling is also not the entire answer, at least as currently implemented. Of all the plastic ever produced, only 9% has been recycled. Ultimately, it seems we need to reduce our global dependence on this substance, and a legally binding international agreement that operates across the entire supply chain is an essential first step.

Without major efforts to reduce plastic pollution, projections show that 12 billion metric tons of plastic waste could end up in the natural environment or landfills by 2050. Image by Lucien Wanda via Pexels (Public domain).

2. Sea level rise

One of the primary drivers of sea level rise is the thawing of global ice. A study published in November provided some bleak news from Greenland’s largest ice sheet, suggesting that it is thawing at an accelerated rate and will add six times more water to the ocean than scientists previously thought. The calculations show that by the end of this century, it will add 0.5 inches to the global ocean level, an amount equal to Greenland’s overall contribution to sea level rise over the past 50 years.

Scientists are closely monitoring the Thwaites Glacier in Antarctica, also known as the “Doomsday” glacier, as a new study shows it is capable of shrinking faster than it has in recent years. The glacier is the size of Florida and accounts for about 5% of Antarctica’s contribution to changes in global sea level; if it were to collapse into the ocean, it could cause a rapid rise in sea levels. Focusing on just the United States, NASA released a study in October showing the average level of sea rise for the majority of coastlines in the contiguous United States could reach 30 centimeters (12 inches) by 2050.

The analysis draws on almost three decades of satellite data, and the results could help coastal communities prepare adaptation plans for the coming years, which may bring an increase in flooding. The estimated waterline increase will vary regionally: 25-36 cm (10-14 in) for the East Coast, 36-46 cm (14-18 in) for the Gulf Coast and 10-20 cm (4-8 in) for the West Coast. Experts cite climate change as a leading cause of the sea level rise, along with natural factors, such as El Niño and La Niña events and the moon’s orbit.

Calculations show that by the end of this century, Greenland’s melting ice will add 0.5 inches to the global ocean level. Image by Marek Okon via Unsplash (Public domain).

3. A major milestone in shark and ray protection

In November, governments from around the world came together at the 19th Conference of the Parties (CoP19) to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) in a massive showing of leadership to increase the protection of nearly 100 species of sharks & rays. CoP19 parties voted to list 54 species of requiem sharks, six species of hammerhead sharks and 37 species of guitarfish under CITES Appendix II.

The designation limits international trade and grants greater protection to these species, many of which are threatened with extinction by the unsustainable global trade in their fins and meat. This is a huge win for shark conservation as it brings 90% of the internationally traded shark species under CITES protection. Previously only 20% had been protected. International trade of these species will only be permitted if they are not endangered as a result, and will require an export permit to ensure that legal and sustainable trade is taking place.

The proposals were championed by Panama, the host country, and co-sponsored by more than 40 other CITES-party governments. It is one of 46 proposals that was adopted by the delegation at the conference and reaffirms international commitments to protect both terrestrial and marine species that are impacted by the global wildlife trade. In addition to the nearly 100 species of sharks and rays, the parties voted to increase the protection of 150 tree species, 160 amphibian species, 50 turtle and tortoise species and several species of songbirds.

In November, governments from around the world came together at the CITES COP19 to increase the protection of nearly 100 species of sharks and rays. Image by Matt Waters via Pexels (Public domain).

4. Momentum builds for a global moratorium on seabed mining

2022 marked a dramatic change in what previously appeared to be an almost inevitable march toward the start of the controversial emerging industry of deep-sea mining. Marine policy experts deemed that the “two-year rule” triggered by Nauru in 2021 had unclear legal footing and implementation, undercutting efforts to see seabed mining start as soon as July 2023 under whatever regulations are in place at the time.

Scientists this year also came together to highlight substantial scientific gaps in our understanding of the environmental impacts of seabed mining. Countries, businesses and scientists also united in strengthening a call for a global moratorium, or pause, on seabed mining. In a major shifting of political winds at the June-July UN Ocean Conference in Lisbon, Pacific states, including Palau, Fiji, Samoa and the Federated States of Micronesia, led an alliance calling for a moratorium. France later became the first nation to call for a complete ban on the activity. Twelve nations have now taken formal positions against deep-sea mining in international waters this year.

Amid this growing opposition, the International Seabed Authority approved its first mining trials since the 1970s. These commenced in September in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone, an area beyond national jurisdictions in the Pacific Ocean that contains rare-earth elements and metals. In November, a new report suggested that seabed minerals may not be necessary at all and that their demand could instead be met by recycling and existing terrestrial reserves.

The deep-sea mining vessel Hidden Gem moored in the Waalhaven port of Rotterdam in 2021. Twelve nations have now taken formal positions against deep-sea mining in international waters this year. Image © Marten van Dijl / Greenpeace.

5. Asia-Pacific ocean leadership

The Asia-Pacific region is home to the most biologically diverse and productive marine ecosystems. The countries in this region are also characterized by having a larger population and stronger economic growth than any other region. And yet many global conversations calling for increased ambition in ocean leadership have historically lacked Asia-Pacific representation. 2022 suggested a turning of that tide. The G20, hosted this year in Indonesia, included an entire summit, the O20, devoted to ocean health issues. There appears to be nascent interest in carrying this leadership tradition forward at the next G20 summit, to be hosted in September by India. Similarly, Japan will host the G7 summit in Hiroshima next May and has engaged in discussions to elevate the UN’s Sustainable Development Goal 14, which deals with the ocean, as a major topic.

With the rising threat of climate change, countries in the Asia-Pacific region have turned their attention this year to blue carbon. China, which lost more than half of its mangrove swamps between 1950 and 2001, is making some initial progress in protecting its marine ecosystem by creating an international mangrove center, national standards for coral reef restoration and its first comprehensive methodology for blue carbon accounting. At COP27, the UN climate conference that took place in November in Sharm El Sheikh, Egypt, the establishment of the International Blue Carbon Institute was announced. The institute will serve as a knowledge hub to develop and scale blue carbon projects. It will be housed in Singapore to focus on supporting Southeast Asia and the Pacific Islands.

Indonesia has taken action to slow the loss of its mangroves, the world’s largest collection, through multiple initiatives such as launching the Mangrove Alliance for Climate. This slow but steady emerging leadership in oceans by countries in the Asia-Pacific region is a promising sign.

The Asia-Pacific region is home to the most biologically diverse and productive marine ecosystems. Image by Kanenori via Pixabay (Public domain).

6. Outer space ocean

Oceans may not be as exclusive to Earth as we previously thought. A new study reveals that 4.5 billion years ago Mars had enough water to be covered in an ocean as deep as 300 meters (nearly 1,000 feet). The Mars that we know in the present day is a reddish color and averages temperatures of negative 62 degrees Celsius (negative 80 degrees Fahrenheit), making it unable to support water in any form other than ice. During the first 100 million years of Mars’ evolution, ice-filled asteroids that carried organic molecules crashed on the planet, allowing for conditions supportive of life to emerge long before they did on Earth.

Because Mars does not have plate tectonics, the surface preserves a historical record of the planet’s history; researchers were able to gain insight into the red planet’s wetter past, as well as into the formation of the solar system, from a meteorite found on Earth that was part of Mars’ original crust billions of years ago.

NASA’s Curiosity Mars rover. A new study reveals that 4.5 billion years ago Mars had enough water to be covered in an ocean. Image by NASA/JPL-Caltech/MSSS.

7. Ocean giants

This year brought both ups and downs for the world’s largest charismatic marine megafauna: whales. Scientists are looking into what is causing a 40% decline in birth rates of the Pacific gray whale (Eschrichtius robustus) population that travels along the U.S. West Coast on its migration from Baja, Mexico, back to the Arctic. This past year’s decline brings the birth rate to the lowest level since 1994. The scarcity of food sources in their Arctic feeding grounds due to climate change is one main factor scientists say they believe is contributing to the decline.

Another study showed that blue, fin and humpback whales feed at 50-250 meters (164-820 feet) below the surface, which coincides with the ocean’s highest concentrations of microplastics. The authors estimated that blues ingest 10 million pieces per day. Some progress was made on mitigating one of the largest threats to large whales: ship strikes.

The waters off the southern coast of Sri Lanka are important blue whale habitat for feeding and nursing, but also a busy shipping lane that creates a high risk for fatal collisions. The largest container line in the world has started ordering its ships to slow down in this region and travel outside the known whale habitat, helping to reduce the risk of collisions by 95%. The tech-driven platform Whale Safe (one of our projects at the Benioff Ocean Science Laboratory), designed to prevent whale-ship collisions and piloted in southern California, was replicated and deployed in the San Francisco region, helping to create a safer environment for whales off the U.S. West Coast.

A study showed that blue, fin and humpback whales feed at 50-250 meters (164-820 feet) below the surface, which coincides with the ocean’s highest concentrations of microplastics. Image by ArtTower via Pixabay (Public domain).

8. Explosive interest in blue carbon

Climate change continues to be the biggest threat facing our ocean and planet. 2022 brought a happy but belated influx of investment and attention to blue carbon, a term that refers to using mangroves, tidal marshes, seagrass beds, and other marine ecosystems to sequester carbon dioxide in the fight against climate change.

Mangroves have the potential to store up to 10 times as much carbon as tropical rainforests. In addition to the pivotal role they might have in preventing climate change, blue carbon ecosystems also protect coastal communities from flooding and storms and provide habitat for marine life. As a result, protecting these marine ecosystems was a key topic at COP27, a focus of research by academic institutes and an area of investment by companies such as Google and Salesforce (whose co-founder, Marc Benioff, also funds the Benioff Ocean Science Laboratory, where we work).

Australia’s national science agency, CSIRO, and Google announced a $2.7 million blue carbon AI research project that will help researchers understand blue carbon ecosystems in the Indo-Pacific and Australia. At COP27, Salesforce, the World Economic Forum’s Friends of Ocean Action and a global coalition of ocean leaders announced the High-Quality Blue Carbon Principles and Guidance, a blue carbon framework to guide the development and purchasing of high-quality blue carbon projects and credits. In the last decade alone, the oceans have absorbed about 23% of carbon dioxide emitted by human activities and investment in their protection and recovery will be vital to the overall fight against climate change.

Mangroves have the potential to store up to 10 times as much carbon as tropical rainforests. Image by Rhett A. Butler/Mongabay.

9. Marine heat waves and coral reefs

Record-breaking heat events took place across the globe this year, and not just on land. Rising ocean temperatures are a cause for concern because they increase stress on already vulnerable ecosystems like coral reefs. The sea surface temperatures over the northern part of the Great Barrier Reef were the warmest November temperatures on record, raising fears this may be the second summer in a row of a massive coral bleaching event that affected 91% of surveyed reefs last year.

The news isn’t all bad, though. Innovative finance mechanisms are being leveraged to protect coral reefs from these threats. In Hawai’i, The Nature Conservancy purchased an insurance policy to protect the state’s reefs from hurricanes and tropical storms. If wind speeds reach 50 knots (57.5 mph) or more, the policy will pay out, allowing for rapid reef repair. This is the first policy of its kind in the U.S., although similar approaches have been used in Mexico, Belize, Guatemala and Honduras. Creative finance solutions like this will continue to be a key component of protecting these vital ecosystems.

The sea surface temperatures over the northern part of the Great Barrier Reef were the warmest November temperatures on record. Image by Rhett A. Butler/Mongabay.

10. A decisive year for the ocean

2022 was a big year for ocean policies, marked by a number of breakthroughs by the international community, some of which had been long-awaited after pandemic-induced delays. Major themes addressed reducing plastic pollution, protecting marine biodiversity, supporting the blue economy, decarbonizing shipping and more. Key policy moments included a landmark deal to ban harmful fishing subsidies that was reached after 20 years of negotiations at the World Trade Organization. The historic agreement specifically prohibits subsidies to illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing and to fisheries targeting overexploited fish stocks. At the UN Ocean Conference, member states made more than 700 conservation commitments pledging to expand marine protected areas, end destructive fishing practices, increase investments and expand blue economies.

More than 100 nations have affirmed voluntary commitments to protect 30% of their oceans by 2030. At the conference, the Protecting Our Planet Challenge announced it will invest at least $1 billion to support this goal. Several countries also announced plans to create and expand marine protected areas, including Colombia, which, if it fully implements its plan, would become the first country to achieve the 30% goal ahead of the 2030 target.

In November, the Green Shipping Challenge launched at COP27, with more than 40 announcements by countries, ports, and companies detailing measures to decarbonize shipping, an industry that currently emits close to 3% of global greenhouse gas emissions. Many of the announcements were related to green shipping corridors and technological developments for climate-neutral ships, such as innovative propulsion systems, sailing cargo ships and the production of low- and zero-emission fuels.

Finally, to cap off 2022, after two years of delay from the pandemic, the UN conference on the Convention on Biological Diversity (COP15) took place in Montreal. Early on the morning of Dec. 19, delegates reached a historic new global biodiversity agreement that outlines 23 conservation targets to prevent biodiversity loss over the next decade, including protecting 30% of land, fresh water and the ocean by 2030. During negotiations, there were strong disagreements among delegates about how much funding was needed to reach these goals and who should pay for it. In the final agreement, nations collectively committed to spending $200 billion per year on biodiversity conservation.

Callie Leiphardt is a project scientist at the Benioff Ocean Initiative, where she works on projects to develop science- and technology-based solutions to ocean problems, such as the Whale Safe project to reduce fatal whale-ship collisions along the California coast. Her background is in conservation planning, particularly with marine mammals. Douglas McCauley is an associate professor at the University of California, Santa Barbara, and director of the Benioff Ocean Science Laboratory. Neil Nathan is a project scientist at Benioff Ocean Science Laboratory, where he works on issues such as deep-sea mining, marine protected areas in the high seas and shark monitoring using drones and artificial intelligence. Nathan has a background in natural capital approaches, which aim to incorporate the value of ecosystem services into decision-making and planning. Rachel Rhodes is a project scientist at the Benioff Ocean Science Laboratory, where she works on Whale Safe. Her background is in marine geospatial data and strategic environmental communications. Aaron Roan leads technology and engineering initiatives across projects at the Benioff Ocean Science Laboratory. He comes from Google and Slack and has spent more than a decade using technology, machine learning and data to help with ocean science and conservation.

Banner image: A whale shark swimming with remoras in Ras Mohammed National Park, Egypt. Image by Cinzia Osele Bismarck / Ocean Image Bank.

Citations:

Geyer, Roland, Jenna R. Jambeck, and Kara Lavender Law. “Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made.” Science Advances 3.7 (2017). doi:10.1126/sciadv.1700782.

Khan, S. A., Choi, Y., Morlighem, M., Rignot, E., Helm, V., Humbert, A., … Bjørk, A. A. (2022). Extensive inland thinning and speed-up of Northeast Greenland ice stream. Nature, 611(7937), 727-732. doi:10.1038/s41586-022-05301-z

Graham, A. G., Wåhlin, A., Hogan, K. A., Nitsche, F. O., Heywood, K. J., Totten, R. L., … Larter, R. D. (2022). Rapid retreat of thwaites glacier in the pre-satellite era. Nature Geoscience, 15(9), 706-713. doi:10.1038/s41561-022-01019-9.

Hamlington, Benjamin D., et al. “Observation-based trajectory of future sea level for the coastal United States tracks near high-end model projections.” Communications Earth & Environment 3.1 (2022). doi:s43247-022-00537-z.

Amon, Diva J., et al. “Assessment of scientific gaps related to the effective environmental management of deep-seabed mining.” Marine Policy 138 (2022). doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2022.105006.

Zhu, Ke, et al. “Late delivery of exotic chromium to the crust of Mars by water-rich carbonaceous asteroids.” Science Advances 8.46 (2022). doi:eabp8415.

Kahane-Rapport, S. R., Czapanskiy, M. F., Fahlbusch, J. A., Friedlaender, A. S., Calambokidis, J., Hazen, E. L., … Savoca, M. S. (2022). Field measurements reveal exposure risk to microplastic ingestion by filter-feeding megafauna. Nature Communications, 13(1). doi:10.1038/s41467-022-33334-5

Wylie, Lindsay, Ariana E. Sutton-Grier, and Amber Moore. “Keys to successful blue carbon projects: lessons learned from global case studies.” Marine Policy 65 (2016). doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2015.12.020

FEEDBACK: Use this form to send a message to the editor of this post. If you want to post a public comment, you can do that at the bottom of the page.

Adaptation To Climate Change, Biodiversity, Climate Change, Climate Change And Conservation, Climate Change And Coral Reefs, Climate Change Policy, Coastal Ecosystems, Commentary, Conservation, Endangered Species, Environment, Environmental Law, Environmental Policy, Environmental Politics, Fish, Fishing, Governance, Impact Of Climate Change, Mangroves, Marine, Marine Animals, Marine Biodiversity, Marine Conservation, Marine Crisis, Marine Ecosystems, Marine Protected Areas, Ocean Crisis, Ocean Warming, Oceans, Oceans And Climate Change, Saltwater Fish, Sea Levels, Wildlife, Wildlife Conservation

Print

These 'floating garbage bins' are mitigating ocean pollution by capturing tons of marine litter

Plastic pollution is among the most pressing environmental issues given the rapid increase of disposable plastic products over the past decade. Every year, about 8 million tons of plastic waste escapes into the oceans from coastal nations, and forecasts suggest this could double by 2025 if drastic action is not taken.

1. Seabin project

Seabin Project is a clean tech startup on an ambitious mission to help solve the global problem of ocean plastic pollution and ocean conservation. Andrew Turton and Pete Ceglinski launched Seabin Project in Australia, back in 2015, to extract plastic from the ocean. As part of the project, floating “seabins” were installed to skim plastics and other debris from harbour water before they can reach the ocean — a key preventive solution previously identified by scientists and conservationists, including the National Geographic Society.

Each bin can capture 90,000 plastic bags a year. Learn more: https://t.co/ZZX0Masf50@Seabin_project pic.twitter.com/o3xjEixIKQ— World Economic Forum (@wef) September 23, 2022

“We are now in the 6.0 (next generation technology), which includes smart technology, water sensors and a modem for cloud-based or IoT connectivity,” said CEO and co-founder Ceglinski, explaining how their commercial product acts as a floating garbage bin and intercepts trash, oil, fuel and detergents. Data estimates suggest their technology with each Seabin allows them to capture 90,000 plastic bags every year for less than $1 a day. The collected debris is then recycled or sent to a waste management facility.

2. Capturing marine litter

The Seabin Project is accelerating its global expansion with the “100 cities by 2050” campaign, selecting Marina Del Rey in Los Angeles as the second city after Sydney, Australia. From July 2020 to November 2022, the project captured 100 tons of marine litter in Sydney, while in Los Angeles, 2.1 tons were captured between July 2022 to November 2022. The city choices weren’t random as the team believes the world’s marinas and ports are the perfect places to start helping clean the oceans.

With no huge open ocean swells or storms inside the marinas, these relatively controlled environments provide the perfect locations for Seabin installations. The Seabin Project

3. A severe problem

Most of the plastic trash in the oceans flows from land. Trash is also carried to sea by major rivers, which act as conveyor belts, picking up more and more trash as they move downstream. The problem increases when plastics break down into microplastics moving freely through water and air. Plastics often contain additives making them stronger, more flexible, and durable. But many of these additives also extend the life of products when they become litter, with some estimates ranging to at least 400 years to break down.

© Seabin Project

Poonam Watine, Knowledge Specialist at the World Economic Forum’s Global Plastic Action Partnership, believes that innovative solutions like the Seabin can prove to be a significant step in the right direction to mitigate and prevent plastic pollution.

“High impact and inspiring trailblazers like Seabin provide a glimmer of hope on how to take action to the impending plastic crisis through alternative solutions,” said Watine.

Five ways sequins add to plastic pollution

Getty ImagesBy Navin Singh KhadkaEnvironment correspondent, BBC World ServiceChristmas and New Year are party time – an occasion to buy a sparkling new outfit. But clothes with sequins are an environmental hazard, experts say, for more than one reason.1 Sequins fall off”I don’t know if you’ve ever worn anything with sequins, but I have, and those things are constantly falling off, especially if the clothes are from a fast-fashion or discount retailer,” says Jane Patton, campaigns manager for plastics and petrochemicals with the Centre for International Environmental Law.”They come off when you hug someone, or get in and out of the car, or even just as you walk or dance. They also come off in the wash.”The problem is the same as with glitter. Both are generally made of plastic with a metallic reflective coating. Once they go down the drain they will remain in the environment for centuries, possibly fragmenting into smaller pieces over time.”Because sequins are synthetic and made out of a material that almost certainly contains toxic chemicals, wherever they end up – air, water, soil – is potentially dangerous,” says Jane Patton.”Microplastics are a pervasive, monumental problem. Because they’re so small and move so easily, they’re impossible to just clean up or contain.”Researchers revealed this year that microplastics had even been found in fresh Antarctic snow.Biodegradable sequins have been invented but are not yet mass-produced.2 Party clothes – the ultimate throwaway fashionThe charity Oxfam surveyed 2,000 British women aged 18 to 55 in 2019, 40% of whom said they would buy a sequined piece of clothing for the festive season.Only a quarter were sure they would wear it again, and on average respondents said they would wear the clothing five times before casting it aside.Five per cent said they would put their clothes in the bin once they had finished with them, leading Oxfam to calculate that 1.7 million pieces of 2019’s festive partywear would end up in landfill.Once in landfill, plastic sequins will remain there indefinitely – but studies have found that the liquid waste that leaches out of landfill sites also contains microplastics.One group of researchers said their study provided evidence that “landfill isn’t the final sink of plastics, but a potential source of microplastics”.Getty Images3 Unsold clothes may be dumpedViola Wohlgemuth, circular economy and toxics manager for Greenpeace Germany, says 40% of items produced by the clothing industry are never sold. These may then be shipped to other countries and dumped, she says. Clothes decorated with sequins are, inevitably, among these shipments. Viola Wohlgemuth says she has seen them at second-hand markets and landfill sites in Kenya and Tanzania.”There’s no regulation for textile waste exports. Such exports are disguised as second-hand textiles and dumped in poor countries, where they end up in landfill sites or waterways, and they pollute,” she says.”It is not banned as a problem substance like other types of waste, such as electronic or plastic waste, under the Basel Convention.” 4 There is waste when sequins are madeSequins are punched out of plastic sheets, and what remains has to be disposed of.”A few years ago, some companies tried to burn the waste in their incinerators,” says Jignesh Jagani, a textile factory owner in the Indian state of Gujarat.”And that produced toxic smoke, and the state’s pollution control board came to know of it and made the companies stop doing that. Handling such waste is indeed a challenge.”One of the developers of compostable cellulose sequins, Elissa Brunato, has said she began by making sheets of material that the sequins were then cut out of. To avoid this problem, she moved to making sequins in individual moulds.High microplastic concentration found on ocean floorBiodegradable litter backed by Sir David AttenboroughWashed clothing’s synthetic mountain of ‘fluff’5 Sequins are attached to synthetic fibresThe problem is not only the sequins, but the synthetic materials they are usually sewn on to.According to the UN Environment Programme, about 60% of material made into clothing is plastic, such as polyester or acrylic, and every time the clothes are washed they shed tiny plastic microfibres.These fibres find their way into waterways, and from there into the food chain.According to one estimate from the International Union for Conservation of Nature, synthetic textiles are responsible for 35% of microfibres released into the oceans. George Harding of the Changing Markets Foundation, which aims to tackle sustainability problems using the power of the market, says the fashion industry’s use of plastic sequins and fibres (derived from oil or gas) also demonstrates a “deeply rooted reliance on the fossil fuel industry for raw materials”.He adds that clothing production is predicted to almost double by 2030, compared with 2015 levels, so “the problem is likely to only get worse without significant interventions”.

The Capitol Christmas tree provides a timely reminder on environmental stewardship this holiday season

WASHINGTON—A ceremony on the Capitol’s West Lawn to light a 78-foot red spruce from Pisgah National Forest earlier this month heralded the festive holiday season. The tree was one of nearly 5 million Christmas trees harvested in North Carolina this year.

“Our Capitol Christmas tree reminds us of the importance of working together to be good stewards of our environment, so that future generations can enjoy the bounties of forests and Christmases still to come,” said Republican Sen. Richard Burr of North Carolina.

The tree will light up the West Lawn until the first week of January, when its wood will be recycled to make musical instruments, according to the U.S. Forest Service. These instruments will be donated to local North Carolina communities.

The tree’s afterlife as newly crafted violins, guitars and mandolins demonstrates one of several sustainable ways to dispose of Christmas trees—a key issue for increasingly climate-conscious consumers weighing the choice between real and artificial trees.

A survey conducted by the National Christmas Tree Association estimated that almost 21 million trees were purchased in the U.S. in 2021. Around 10 million artificial trees are reported to be purchased each season.

The growth of the artificial tree market has had an acute impact on growers with consumer preferences shifting towards artificial trees over the past 30 years, said Jill Sidebottom of the National Christmas Tree Association.

The reason for the shift is likely multi-faceted. The Association’s survey found that the median price of a real tree in 2021 was $69.50. Higher costs of production and constrained supply means this will likely increase this year, according to a New York Times analysis. The shortage in supply can be partially attributed to planting decisions made a decade ago, the newspaper said. Trees must grow for five to 15 years before they are ready to be harvested.

Artificial trees, which also retailed at a median price of $70 in 2021, may also become more expensive as production and transport costs increase globally. However, these can be re-used for many years, making them more affordable in the long run.

A comparison between real and artificial trees has left some consumers concerned about the sustainability of purchasing real trees. The debate is a nuanced one. Real trees capture and store carbon during their lifetime. However, once cut down for Christmas, their potential to harm the environment depends on those who buy and dispose of them.

According to Ian Rotherham, emeritus professor at Sheffield Hallam University in England and a researcher on wildlife and environmental issues, the comparison must involve more than just the act of cutting down trees.

“If you’re cutting down a Christmas tree from a mixed-age plantation, where you take some of the trees out and you leave some in, that actually has no impact on the carbon capture of that plantation because the trees will compensate relative to the space that you’ve freed up,” he said.

Harvesting a large number of trees that are the same size and age at once will have some impact. However, “they will probably then replant another crop into that same space … So, to some extent that will balance, so long as you are then disposing of the tree when you have used it in a responsible way,” he said.

For every Christmas tree harvested in the U.S., one to three seedlings are planted the following spring, according to the National Christmas Tree Association.

The best option for the environment, in Rotherham’s view, “depends on what you do with it after you’ve used them.”

A real tree that is dumped in a landfill will produce methane as it decomposes. Methane is a greenhouse gas that has more than 80 times the warming power of carbon dioxide over the first 20 years after it reaches the atmosphere. While carbon dioxide has a longer-lasting effect on the climate, methane drives the speed of warming in the near term.

The methane produced by a two-meter tree as it decomposes is equivalent to emitting 16 kilograms of carbon dioxide, according to Carbon Trust, a U.K.-based nonprofit focused on climate change and carbon emissions. If all 21 million U.S. consumers who purchased a real Christmas tree last year disposed of it in landfill, the climate impacts would be the equivalent of 42,283 homes’ energy use for one year, according to an analysis using EPA data.

Keep Environmental Journalism AliveICN provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going.Donate Now

Is ‘chemical recycling’ a solution to the global scourge of plastic waste or an environmentally dirty ruse to keep production high?

Diplomats negotiating guidelines for an international convention on hazardous wastes this month in Switzerland debated a new section on the “chemical recycling” of plastic debris fouling the global environment.

The 1989 Basel Convention, which seeks to protect human health and the environment against the adverse effects of hazardous wastes, was updated in 2019 when 187 ratifying nations agreed to place new restrictions on the management and international movement of plastic wastes—and to update the treaty’s technical guidelines.

Since then, the plastics industry has tried to quell mounting anger over vast mountains of plastics filling landfills and polluting the oceans by advancing chemical recycling as a means of turning discarded plastic products into new plastic feedstocks and fossil fuels like diesel.

Scientists and environmentalists who have studied the largely unproven technology say it is essentially another form of incineration that requires vast stores of energy, has questionable climate benefits, and puts communities and the environment at risk from toxic pollution. Some of them even view the inclusion of the chemical recycling language in the implementing guidelines as a threat, although it remains to be seen what that language will ultimately say.

“The text is nowhere near settled,” said Sirine Rached, the global plastics policy coordinator for the Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives (GAIA), which with the Basel Action Network has called chemical recycling of plastics “a fantasy beast that has yet to establish its efficacy and economic viability, while already exhibiting serious environmental threats.”

Rached said the group’s “priority is for the guidance to focus on environmentally-sound management and to refer to technologies only on the basis of sound peer-reviewed references, and not on industry marketing claims, and this involves not speculating on how technologies may or may not evolve in future.”

“The solution is making less plastic,” Judith Enck, founder and president of the environmental group Beyond Plastics and a former EPA regional administrator, told a subcommittee of the Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works at a hearing on Dec. 15.

U.S. lawmakers are weighing their own ideas for addressing the plastics crisis. “We need to cut plastic production by 50 percent in the next 10 years, and we can do it,” she told them, adding that chemical recycling produces “more fossil fuel and the last thing we need is more fossil fuel.”

Such a dramatic cut in plastic would devastate the economy, said Matt Seaholm, chief executive officer of the Plastics Industry Association, which represents companies that produce, use and recycle plastic. “Our industry wants to recycle more,” and deploying more mechanical recycling and chemical recycling will help, he told lawmakers. “We love plastic,” he said. “We hate the waste. We need to collect, sort and ultimately reprocess more material.”

Wide agreement exists that the 11 million metric tons of plastic pollution that enters the oceans every year “is devastating,” Erin Simon, head of plastic waste and business for the World Wildlife Fund, a conservation group that operates in 100 countries, said in an interview. “It’s wreaking havoc on our species, our ecosystems and in the communities that depend on them.

“You really do need this coordinated global structure” that treaties can provide, she added. “Because it’s clear that it’s not going to happen just with voluntary initiatives alone.”

Writing Guidelines for Chemical Recycling

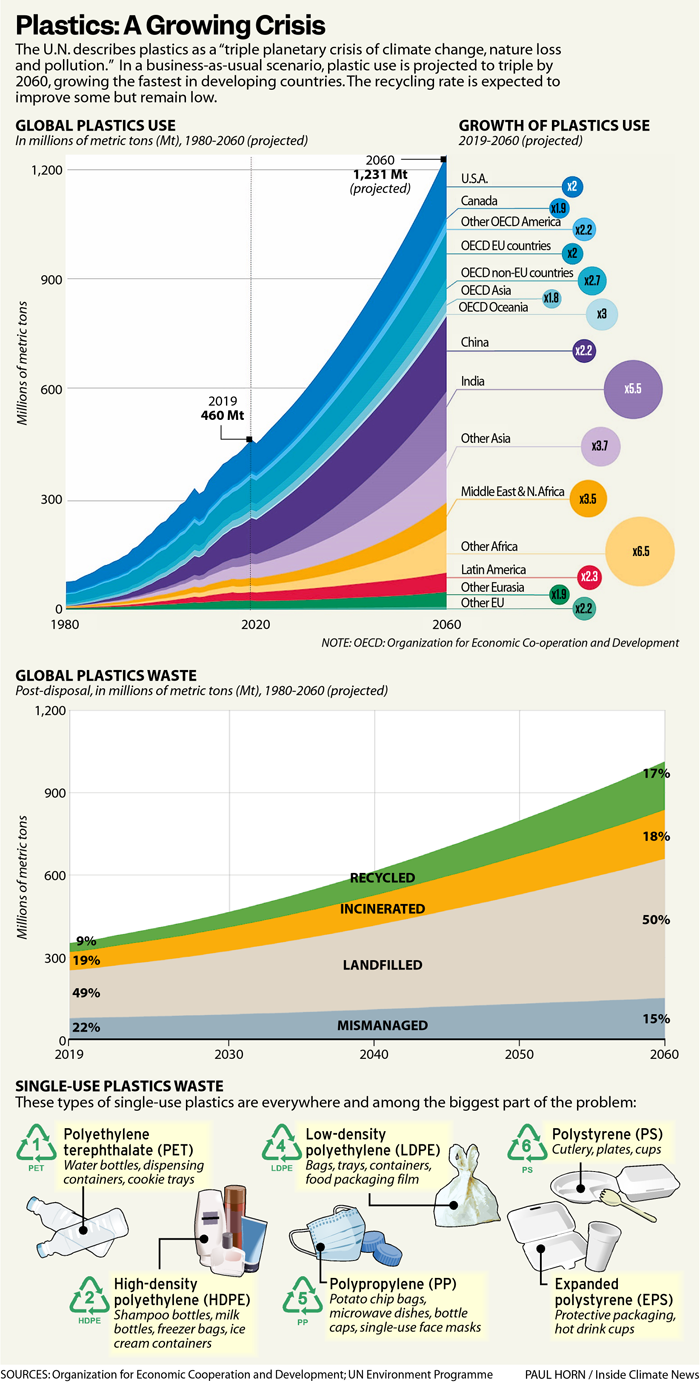

The world is making twice as much plastic waste as it did two decades ago, with most of the discarded materials buried in landfills, burned by incinerators or dumped into the environment, according to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, a group that represents developed nations. Production is expected to triple by 2060. Globally, only 9 percent of plastic waste is successfully recycled, according to OECD.

Nearly all of the plastic that gets recycled goes through a mechanical process involving sorting, grinding, cleaning, melting and remolding, often into other products. But mechanical recycling has its limits; it does not work for most kinds of plastic and what gets recycled, such as certain kinds of bottles and jugs, can only be recycled a few times.

Chemical recycling consists of new and old technologies, hailed by the industry but seen as an unproven marketing ruse by environmentalists, that governments must now study and regulate if they are to successfully confront a menacing problem that spans the Earth and has even invaded our bodies with microplastic particles.

A Basel Convention committee met in the second week of December in Switzerland to debate whether the Basel treaty’s technical guidelines should be updated to include chemical recycling, which is also sometimes referred to as “advanced recycling,” and if so, under what terms.

The debate occurred within the framework of the Basel Convention and any language on chemical recycling that makes it into its technical guidelines will be seen as acceptable tools for managing plastic waste. The guidelines are likely to carry over into the negotiations over the next two years on an international treaty governing plastic pollution and ongoing plastics manufacturing.

Those treaty talks have barely begun, with a first negotiation session among delegates a few weeks ago in Uruguay.

The technical guidelines for the Basel Convention are supposed to represent the best available technology for protecting humans from various hazardous wastes, said Lee Bell, an Australia-based policy advisor for the International Pollutants Elimination Network (IPEN). He is also the co-author of a 2021 IPEN study that detailed how chemical recycling generates dangerous dioxin emissions, produces contaminated fuels and consumes large amounts of energy.

“Many parties and observers are of the view that there is no proof that chemical recycling is what you would call best available technology … or best environmental practice,” he said.