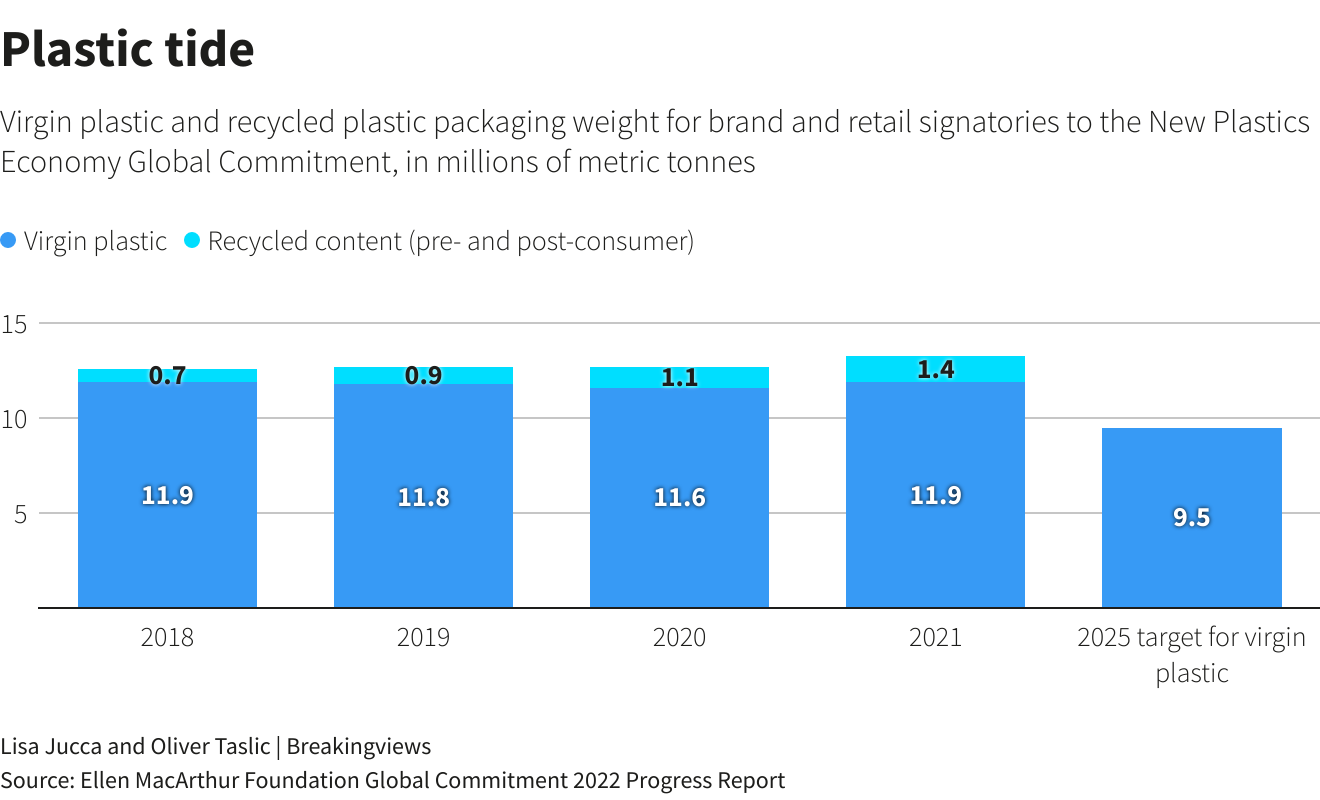

MILAN, Jan 13 (Reuters Breakingviews) – Investors should worry about a rising plastic tide. The pandemic and a war in Ukraine have focused money managers’ attention on supply chain disruption and energy security risks. Yet as the world continues to drown in packaging waste, the public and private sectors may come after big users like PepsiCo (PEP.O), Coca-Cola (KO.N) and Mars.Four years after the consumer goods giants signed up to voluntary reduction targets under the New Plastics Economy Global Commitment, progress is disappointing. Ellen MacArthur Foundation data shows that the packaging employed by companies like PepsiCo, Mars and Coca-Cola increased its usage of virgin plastic, made from fossil fuels rather than recycled materials, by 5%, 3% and 11% respectively between 2019 and 2021. That makes it unlikely they can meet their commitments to curb its use by 5%, 20% and 25% by 2025.Big plastic users are also making insufficient progress in using recycled material. The latter amounts to just 10% of plastic packaging used by pact signatories. Reusable containers, the most environmentally friendly form of packaging, amounted to only 1.2% of the total in 2021, and that figure is decreasing.Despite citizens’ effort to sort out used plastic for collection, especially in Europe, only 9% actually gets recycled each year, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development says. In the United States 73% of plastic waste ends up in landfills, where it takes up to 500 years to decompose. The rest gets incinerated or washes up on developing countries’ shores. That will only worsen as annual demand of about 450 million tonnes a year is expected to treble by 2060.Solving the plastic challenge is complex and expensive. Plastic comes in different types that cannot be bundled together. Certain materials or additives make it difficult to recycle. Substituting plastic with biodegradable material can be expensive. Using recycled plastic, while less energy-intensive than creating virgin plastic, can cost more overall.Yet, having pledged to act, big corporates are in a vulnerable position. Danone (DANO.PA) is facing a legal challenge over its plastic use. In March, 175 governments agreed to work out binding laws to end plastic pollution by end-2024. Around 70% of citizens surveyed last year in 34 countries want new anti-plastic rules.European investors’ greater focus on sustainability means they are more likely to hassle domestic laggards. But if governments decide to implement mandatory recycling quotas, rival U.S. late-starters would suffer the most. In a worst-case scenario, companies could face a collective $100 billion annual bill if lawmakers ask them to cover waste management costs in full, the PEW Charitable Trusts says.For investors, plastic inaction could become toxic.Reuters GraphicsFollow @LJucca on Twitter(The author is a Reuters Breakingviews columnist. The opinions expressed are her own. Updates to add graphic.)CONTEXT NEWSRepresentatives of 175 countries endorsed in March a landmark resolution to develop international legally binding instruments to end plastic pollution. Negotiations on the new legal instruments kicked off on Nov. 28 with the aim of finalising a binding agreement by 2024.Germany will ask makers of products containing single-use plastic to contribute to the cost of collecting litter in streets and parks from 2025 by paying into a central fund managed by the government. In 2008 the Netherlands introduced a packaging waste management levy.Corporate signatories of the New Plastics Economy Global Commitment launched by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation and the U.N. Environment Programme in 2018, which include PepsiCo, the Coca-Cola Company, Nestlé, Danone and Unilever, are likely to miss several if not all of their targets for tackling plastic pollution. That’s according to progress report by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation published in November.Collective use of virgin plastic by the signatories of the anti-plastic pact has risen 2.5% year-on-year to 11.9 million metric tonnes in 2021, bringing it to the same level it stood at in 2018. Meanwhile, the share of reusable plastic in packaging has fallen to an average 1.2% of total, the report showed.Editing by George Hay, Streisand Neto and Oliver TaslicOur Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles.Opinions expressed are those of the author. They do not reflect the views of Reuters News, which, under the Trust Principles, is committed to integrity, independence, and freedom from bias.

Category Archives: Land

‘Forever chemicals’ expose need for systemic changes

Going back in time can reveal how far we still have to progress. In researching per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) for a recent article series, I found myself ricocheting between the present and the 1950s and 1960s. That was when the vast class of fluorinated compounds commonly dubbed “forever chemicals” first came into widespread use, morphing from wartime applications to a cluster bomb of consumer and industrial uses.

The pesticide industry was also “a child of the Second World War,” biologist Rachel Carson wrote in her magnum opus “Silent Spring,” published 60 years ago last fall. Synthetic insecticides had “no counterparts in nature,” she observed, yet “we have allowed these chemicals to be used with little or no advance investigation of their effect” on ecosystems or ourselves. Like pesticides, PFAS shot from laboratory to market without thorough safety testing, endangering public health and wildlife.

Despite subsequent advances in environmental legislation over the intervening decades, the U.S. approach to chemical regulation remains largely unchanged. We are still subjected to what Carson aptly termed an “appalling deluge of chemical pollution.”

Catering to corporations

Writing in The New Yorker shortly after Carson’s death in 1964, E.B. White noted a “basic flaw in our regulatory machinery. American justice holds the accused person innocent until proved guilty; somehow this concept has crept over into industry, where it doesn’t belong, and has been applied to products of all kinds. Why should a poison dust or spray… enjoy immunity while there is any reason to suspect that it may endanger the public health or damage the natural scene?”

Congress had a chance to correct this fundamental injustice when it enacted the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA) of 1976, but it let corporate priorities prevail. The law instructed the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to adopt those regulations “least burdensome” to industry, and it permitted continued use of roughly 60,000 chemicals (including the earliest ‘legacy’ PFAS) without review of their health risks.

An effort to strengthen TSCA in 2016 encountered strong industry pushback and accomplished only minimal reform, according to a recent ProPublica report. The workload of the agency’s chemical division grew markedly as it strove to undertake more chemical reviews, but its funding remained stagnant.

Greatly increasing the funding and staffing of EPA’s chemicals division would certainly improve chemical oversight, observed Kyla Bennett, an ecologist and lawyer who directs science policy for Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility (PEER), a nonprofit that supports whistleblowers and is pushing the EPA to protect consumers from PFAS in fluorinated plastic containers. “EPA doesn’t have the money, the bodies and the right expertise,” she said, nor does it have adequate time for evaluating new chemicals given a tight, statutory cutoff. The metric for success is “how many of these [approvals] they’ve gotten out in 90 days, not how well they’re protecting human health.”

“The whole system is broken,” Bennett added, due to corporate capture of the regulatory process — a dynamic she said persists under both Democratic and Republican administrations. Supervisors cycle from the agency to industry and back, and whistleblowers report that EPA managers change scientific conclusions, delete critical information and expedite approval of new chemicals to appease manufacturers.

Corporations are mandated to submit studies documenting safety risks, but in 2019 the agency stopped sharing those publicly and made the data difficult for their own staff to access, whistleblowers report. According to Bennett, even some safety data sheets — designed to inform workers and consumers of hazards—are now heavily redacted. Or, in place of where the form should appear in the database, there’s a blank page with a single word: “sanitized.”

A decade before the EPA was established, Carson had already observed the deference given to chemical manufacturers in what she called “an era dominated by industry, in which the right to make a dollar at whatever cost is seldom challenged.” Now, it appears that ‘right’ is almost never challenged: Among 3,835 new chemical applications submitted in the five years leading up to July 2021, journalist Sharon Lerner reported, EPA’s division of new chemicals did not decline a single one.

‘Regrettable substitutions’

Presented with clear evidence in 2001 that PFAS were endangering human health, the EPA negotiated a voluntary phaseout with some leading manufacturers for two PFAS compounds (among an estimated 4,700 in commercial use). In place of those ‘legacy’ compounds, the EPA permitted manufacturers to produce a second generation (“GenX”) of PFAS even though industry studies had demonstrated their health risks, Lerner revealed.

GenX is a classic case of a “regrettable substitution,” what Harvard University public health professor Joseph Allen defines as “the cynical replacement of one harmful chemical by another equally or more harmful in a never-ending game being played with our health.”

Industry always has the upper hand in this whack-a-mole “game” due to the sheer volume of new chemicals generated. The U.N. Environmental Programme reports that in 1965, a new chemical substance was registered on average every 2.5 minutes. Now, it’s every 1.4 seconds. The EPA is mandated to test 20 new chemicals a year but it’s failing to meet even that modest target.

The Precautionary Principle

Europe, in contrast, is moving away from the whack-a-mole approach to chemical management. According to the European Environmental Bureau, the European Commission plans to implement “a group approach to regulating chemicals, where the most harmful member of a chemical family defines legal restrictions for the whole family. That should end an industry practice of tweaking chemical formulations slightly to evade bans.”

For more than a decade, Europe has applied a common-sense restraint known as the Precautionary Principle in chemical regulations — requiring industries to assess risks and share data on hazards before substances go to market. Whereas in the U.S., chemicals are readily approved and only withdrawn when there is irrefutable evidence of human harm, often after decades of use.

While questions remain about the timeline and resources for implementing Europe’s new chemicals “Restrictions Roadmap,” the European Union has already banned about 2,000 chemicals since adopting a more precautionary approach. An additional 5,000 to 7,000 chemicals could be banned by 2030 under the new roadmap.

Paring back to essential uses and increasing transparency

Maine is pioneering a path that a growing number of scientists and policy specialists advocate — banning all PFAS except those deemed — in the language of LD 1503 — “essential for health, safety or the functioning of society and for which alternatives are not reasonably available” (such as critical medical devices).

A recent study found that alternatives exist for many consumer uses, but that options for industry substitutes are harder to assess—given a culture that keeps much production information proprietary. Far too often, companies use their right to confidential business information “as a cloak to keep things from the public and that’s wrong,” Bennett said.

3M, a leading manufacturer of PFAS, knew about the health risks of its formulations for half a century, evidence in lawsuits has revealed. Recently, the corporation announced plans to phase out PFAS manufacturing and use by 2025, but lack of transparency around how it defines and formulates these chemicals makes the outcome ambiguous. Its action comes in the face of mounting pressure from investors and tens of billions in anticipated litigation settlements as communities around the globe seek damages from chemical manufacturers for poisoned waters and health impacts that begin even before birth, resulting in “pre-polluted babies.”

Chemical corporations may not adopt greater transparency until forced to. But governments working to regulate and remediate PFAS can show the way. For the most part, Maine is making a good-faith effort to share information openly: posting data on sludge and septage sites to be tested, results from landfill leachate tests and public drinking water supply tests, updates on the status of the state’s well-testing, and recorded meetings of the PFAS Fund Advisory Committee.

The state could further improve information-sharing by hiring an ombudsperson to field residents’ questions and concerns, creating a more intuitive and readily linked web interface, and openly strategizing how to address the vast gap that remains between needs for PFAS water testing and treatment and agency capacities. Residents I interviewed in hard-hit areas voiced frustration over not having anyone to advocate for them within state government, feeling they were “put on the back burner” and might be left on their own without further help.

With Maine now mandating PFAS reporting from manufacturers, state agencies will need to resist the regulatory “corporate capture” evident at the federal level.

Open sharing on the part of government is essential on practical grounds — to expedite getting clean water to those still drinking PFAS, to facilitate a rapid transition to new product formulations, and to keep people informed about rapidly evolving science and policy.

More fundamentally, transparency can help to right a pernicious wrong. PFAS pollution represents a devastating betrayal of people who placed their faith in government to protect them and in corporations to consider the greater good. Choices made over decades in corporate board rooms, EPA offices and the halls of Congress violated that public trust.

“Who has decided — who has the right to decide — for the countless legions of people who were not consulted…,” Rachel Carson wrote about the indiscriminate use of toxic chemicals. In the case of PFAS, a small cadre chose the allure of big profits over the well-being of the world. If we hope to reverse those priorities in the years ahead, those who were “not consulted” will need to speak out.

Venice’s lagoon of 2,000 lost boats: the true cost of dumping small vessels

Venice’s lagoon of 2,000 lost boats: the true cost of dumping small vessels For decades, the city’s wetland has been used as a landfill for discarded wrecks, leaking microplastics and pollutants and posing a risk to others on the waterPaolo Cuman points to a rusty boat, half-sunk in Venice’s lagoon. “It has been there for years,” he says, laughing. “When I manage to have her removed, I’ll open a bottle of good wine.” Hunting abandoned boats is a hobby for Cuman, the coordinator of the Consulta della Laguna Media, a grassroots group monitoring the health of the lagoon. Once he’s found the boats, he maps them and pressures the authorities to remove them.For decades, the Venetian lagoon – the largest wetland in the Mediterranean – has been used as a landfill by people wanting to get rid of their boats. An estimated 2,000 abandoned vessels are in the lagoon, scattered over an area of about 55,000 hectares (135,900 acres). Some lie beneath the surface, others poke above the water and some are stranded on the barene – the lowlands that often disappear at high tide.The wrecks are a threat to other vessels – a boat’s engine may be damaged if it passes over them. But they are an even bigger threat to the ecosystem, leaking chemicals, fuel and microplastics as the boats disintegrate in the water.Authorities seldom remove these wrecks; bureaucracy is slow and dealing with the city’s boat graveyards is a long way down the priority list. That’s why a group of boating enthusiasts and environmentalists, including Cuman, are trying to force action.On a hot summer day, the lagoon, which is only a few miles away from the crowded streets of Venice, feels like a world away. Sailboats zigzag across the water, cormorants fly past and flamingos wade in the shallows, while fish leap in and out of the water.Only the wrecks of abandoned vessels mar the scene. For the most part they are small, low-powered motorboats, or burci – transport boats widely used in Venice. These are “owned by ordinary people”, says Cuman.He spots the relic of a vessel: “See this fishing boat? I remember when it used to bring the fish to Mestre [his neighbourhood] 40 years ago! Looks like it has been discarded for three decades at least,” he says.The practice of illegally abandoning vessels in the lagoon dates back to the 1950s, when trucks began to replace boats for commercial purposes. “In the past, the large shipping companies abandoned the burci here, creating boat cemeteries,” says Giovanni Cecconi, president of Venice Resilience Lab, an environmental group that has contributed to mapping the lagoon.“There are boats that have been abandoned for 20 or 30 years that are in very bad condition,” says Davide Poletto, executive director of the Venice Lagoon Plastic Free organisation. These release chemical contaminants as they break down, he says.Modern boats tend to have fibreglass hulls, which release microplastics as they decompose. A big concern is anti-fouling paints, which are intended to keep slime, barnacles and other creatures off the boats. Some of these, such as tributyltin, are now banned because of their toxic effects on marine life. Even the boats’ furnishings and upholstery contain chemicals that may contaminate the water.To a Venetian, owning a boat is almost like owning a car. But while a car might end up in a salvage yard, disposing of an unserviceable boat is complicated and expensive. Venice lacks the infrastructure to deal with unwanted boats; few facilities take them so many choose to abandon them.The Venice lagoon is controlled by 26 different entities, which means it is not always clear who has responsibility.‘A search for ourselves’: shipwreck becomes focus of slavery debateRead more“Even if a local policeman sees an abandoned boat on a sandbank, he cannot intervene to remove it, because it is not his jurisdiction,” says Paolo Ticozzi, a city councillor who says he has asked authorities to create a disposal site for abandoned boats, but has yet to receive an answer.Consulta della Laguna Media says it is the only organisation mapping the wrecks, and that it only covers the northern part of the lagoon.No attempt has been made to quantify the environmental impact of the vessels, according to Venice Lagoon Plastic Free.“No one has thought of analysing the damage caused by boats that have been there for 20, 30 or even 40 years,” says Poletto. The association has funding to remove some of the wrecks and plans to collect and examine some of the sludge at those sites.Venice is far from the only boat graveyard. About 3m shipwrecks of all kinds are scattered across the world, according to Unesco. In the UK, hundreds of boats lie abandoned along the coasts of Devon and Cornwall, according to a BBC report, which called the practice “the fly-tipping of the maritime world”.In the US, a Washington state programme has removed about 900 abandoned boats from rivers since 2002. In 2021, Virginia created a working group to “coordinate an examination of the issues” around abandoned and derelict vessels.“The situation must be evaluated case-by-case,” says the bioscientist Prof Monia Renzi. “Obviously, a boat that has just been sunk should be recovered, if technically possible, because it could release a large number of contaminants even from parts we don’t normally think of, like upholstery.”It can be different for vessels that have been lying on the sea – or riverbed for many decades, where an ecosystem has formed around the ships: “Marine sedimentation above the wreck limits the spread of contaminants,” says Renzi, adding that removing some of the oldest wrecks could cause further damage.When it comes to Venice’s lagoon, however, the best solution is usually to remove the wrecks regardless of their age, says Renzi, especially because shallow waters make recovery easier.Bulky material like boats can reduce the water’s natural circulation, she says, damaging the wider ecosystem – the less water circulates, the more pollutants will stick around. These environments are “already under pressure, because they are highly exploited for fishing, so the possible transfer of contaminants can be extremely critical”, she says. It risks further damaging fish populations.In Venice, however, activists have won a small victory. The authority responsible for water management in the Venetian lagoon, the Magistrato alle Acque, has agreed to remove some vessels in the coming months.Cuman welcomes the news, but says a lot remains to be done.It is not only a problem for the environment, he says, but also of transport within the lagoon: “Unbound boats are at the mercy of the wind and the current. If you pass over a sunken or semi-sunken boat, it can break the engine, causing considerable damage,” says Cuman. Broken-off boat parts floating on the currents can also cause accidents hundreds of miles from the wreck, he says.Cuman wants more people to join his wreck-spotting missions. “If I convince others in this community to join me, then there will be a Venetian patrolling every spot of the lagoon. Ignoring us will become impossible.”TopicsEnvironmentShipwreckedVenicePollutionfeaturesReuse this content

‘A drop in the ocean’: England bans some single-use plastics – but does it go far enough?

Single-use plastic items including cutlery and plates will soon be banned in England, the government has announced.Each year, the country uses around 1.1 billion single-use plates and 4.25 billion items of cutlery, according to government estimates. Only 10 per cent of these are recycled.Now, environment secretary Thérèse Coffey has confirmed that such items will be outlawed in England.Similar bans are already in place in Scotland and Wales.‘A plastic fork can take 200 years to decompose’Plastic objects used for takeaway food and drink – including containers, trays and cutlery – are the biggest polluters of the world’s oceans, studies have shown.“A plastic fork can take 200 years to decompose, that is two centuries in landfill or polluting our oceans,” says Coffey.Billions of single-use plastic items are disposed of each year in England, rather than recycled.England bans single use plasticEngland is now set to ban single-use items including plastic plates, knives and forks.The decision comes after a consultation by the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) that took place from November 2021 to February 2022.“I am determined to drive forward action to tackle this issue head on,” Coffey says.“We’ve already taken major steps in recent years – but we know there is more to do, and we have again listened to the public’s calls.“This new ban will have a huge impact to stop the pollution of billions of pieces of plastic and help to protect the natural environment for future generations.”However, some campaigners have criticised the ban for its limited scope.“Whilst the removal of billions of commonly littered items is never a bad thing – this is a very long overdue move and still a drop in the ocean compared to the action that’s needed to stem the plastic tide,” tweeted Megan Randles, a political campaigner at Greenpeace UK.What items will be included in England’s single-use plastic ban?The government is yet to release details of the single-use plastic ban.On Saturday, more information will be announced about the objects included and where the ban will apply.The ruling will cover plastic plates, bowls and trays used for food items consumed in a restaurant or cafe, the Daily Mail reports, but not in environments like supermarkets and shops.What other European countries have banned single use plastic?A similar ban has already been introduced in Scotland and Wales. In England, single-use plastic straws, stirrers and cotton buds were outlawed in 2020.Green campaigners in England have criticised the government’s delay in bringing in the new measures.The country lags behind the EU, which introduced a ban on single-use plastic items in 2021. The ruling prohibits the sale of common pollutants including straws, plastic bottles, coffee cups and takeaway containers on EU markets.Although not in the EU, Norway also adopted the measures.Further proposals have recently been made to ban miniature hotel toiletries, among other items, as part of the European Green Deal’s fight against packaging waste.In Germany, plastic manufacturers will have to begin paying towards litter collections in 2025.

ClientEarth set to take Danone to court over its plastics footprint

Danone owns brands including evian, Volvic, Activia and Actimel The environmental law firm has today (9 January) confirmed its filing of a case at the Paris Tribunal Judiciaire, accusing Danone of flouting its requirements under the French Duty of Vigilance law. Danone has stated that it is “very surprised” by the move and “strongly refutes” ClientEarth’s claims.

This law was implemented in 2017. It requires large businesses headquartered in France to publish ‘vigilance’ plans each year, setting out the environmental and social risks and impacts of their operations, suppliers and subcontractors. The plan must be global in scope and cover all owned brands and subsidiaries. As well as identifying risks, plans have to include prevention and mitigation measures and information on how the company is implementing these measures and results delivered so far.

ClientEarth is arguing that, as a major plastic packaging producer and distributor, Danone should be obliged under this law to include measures on plastics pollution across the value chain. Danone sells products in more than 120 countries and, according to Break Free From Plastic, is one of the world’s ten largest plastic packaging producers. The campaign also dubbed Danone the top plastic polluter in Indonesia.

In announcing the case, ClientEarth does acknowledge that Danone has implemented a plan relating to plastics. However, it criticizes the corporate’s decision to focus on recycling after consumer use., citing stagnating plastic recycling rates in major economies in the Global North and poor recycling infrastructure development in the Global South. Danone is targeting 100% recyclable or reusable packaging by 2025 and its latest annual report reveals that a proportion of 81% has been achieved.

“Recycling is a limited solution as only 9% of plastics ever made have been recycled,” said ClientEarth’s plastics lawyer Rosa Pritchard. “It’s unrealistic for food giants like Danone to pretend recycling is the silver bullet.”

Without adequate recycling, ClientEarth is arguing, plastics pose an array of environmental risks. These include emissions associated with landfilling, dumping and burning, plus the impact of plastic pollution on nature and human health. Research is ever-evolving on this latter topic. One recent study at the University of Hull found that members of the general public are ingesting microplastics “at levels consistent with harmful effects on cells, which are in many cases the initiative event for health effects”. Effects include disruption to hormone imbalance, organ inflammation and allergic reactions.

ClientEarth also mentions the social impact of plastics. This includes exposure to chemicals in the production process and informal waste management space, particularly in low-income nations.

ClientEarth is asking Danone to measure its plastic use across the value chain, including logistics and promotions. It then wants Danone to map the impact that plastics have on the environment and on humanity across its entire value chain.

From there, the company would be able to update its plastic plan. ClientEarth wants a commitment to reduce absolute plastic use over time.

These measures could be forced by a court intervention or agreed upon outside of court. The court will decide when to hold an initial hearing in the coming weeks and will likely set a date in the first half of the year if it does decide that a lawsuit should be opened.

Supporting ClientEarth with this case are the non-profit Surfrider and NGO Zero Waste France.

Danone’s response

edie approached Danone for a comment. A spokesperson said: “We are very surprised by this accusation, which we strongly refute. Danone has long been recognized as a pioneer in environmental risk management, and we remain fully committed and determined to act responsibly.”

The spokesperson went on to call Danone’s plastics targets “comprehensive”, covering reuse, recycling and alternative materials. They also noted Danone’s support of strong international agreements, through the UN, on a new plastics treaty: “Putting an end to plastic pollution cannot come from one single company and requires the mobilisation of all players, public and industrial, while respecting the imperatives of food safety. This is why we support the adoption, under the aegis of the UN, of a legally binding international treaty.”

Negotiators have until 2024 to finalise the treaty, following agreement on the broad terms last year.

Published 9th January 2023

© Faversham House Ltd 2023 edie news articles may be copied or forwarded for individual use only. No other reproduction or distribution is permitted without prior written consent.

Study: Most farmers recycle plastic waste, but burning persists

A new study has found that the majority of farmers recycle agricultural plastic waste, but illegal burning and burying still persists on some farms.

The survey of 430 farmers on their attitudes towards the disposal and management of agricultural plastic is part of current PhD research on microplastics in soils being carried out by Clodagh King at Dundalk Institute of Technology (DkIT).

The research, which also examined farmers’ awareness and perceptions of the impacts of microplastics and plastics on the environment, was recently published in the internationally-respected journal, Science of the Total Environment (STOTEN).

Clodagh King

Over 88% of farmers who took part in the survey said that they are concerned about the amount of plastic waste generated by agricultural activities.

Most farmers view agricultural plastics negatively because of their environmental impact, along with the cost and logistics involved in dealing with them.

The study concluded that most farmers recycle their agricultural plastic.

The rate of recycling carried out by farmers was dependent on a number of factors including the type of plastic involved, the cost of recycling, access to facilities and knowledge about what can be recycled.

However, some farmers “openly admitted” to burning and burial of plastic waste on their farms, which is not only illegal but damaging to the environment.

The researchers recommended that initiatives should be rolled out to educate farmers on how to recycle farm plastics properly.

Plastic waste

Large pieces of plastic which are not properly managed can disintegrate into microplastics and make their way into soils, surface and groundwater sources.

Around 58% of farmers were “relatively aware” of microplastic pollution, but overall felt that they were more knowledgeable about plastic pollution.

More farmers also believed that aquatic environments are at greater risk to plastic pollution than the terrestrial environments.

Clodagh King in the laboratory at DkIT

The study, led by Clodagh King, recommended that future research efforts must focus on plastic and microplastic pollutions in soils to inform policy and to create greater public awareness of this issue.

It also outlined that new research is needed into the economic and practical viability of biobased and biodegradable plastics for use in agriculture.

“The findings from our study suggest that combined efforts by governments, policy makers, and other stakeholders must be undertaken to reduce the plastic and microplastic problem, it’s an environmental problem that we collectively must come together to solve,” King said.

In Iceland, start-up founders invent new ways to tackle environmental crises

REYKJANES PENINSULA, Iceland — The electric red and green glow of the production facility resembles the Icelandic aurora borealis. Algae in their growth stage flow through hundreds of glass tubes that travel from floor to ceiling, all part of a multistep process yielding nutrients for health supplements. Soon, all parts of each alga will be used.The facility, operated by Icelandic manufacturer Algalif, is a space of inspiration for Julie Encausse, a 34-year-old bioplastic entrepreneur. During a July summer storm, Svavar Halldorsson, an Algalif executive, was guiding her through a tour of the company’s newest facility on the Reykjanes Peninsula.By the end of 2023, this new facility aims to triple its production. After Algalif dries the microalgae and extracts oleoresin, a third of this output then goes toward health supplements. Algalif has traditionally used the rest as a fertilizer. Now Encausse, founder and chief executive of the bioplastic start-up Marea, hopes to use that leftover biomass to create a microalgae spray that can reduce the world’s reliance on plastic packaging.Her newest partnership with Algalif is part of a start-up network in Iceland that focuses on inventive and creative technologies to address the climate and sustainability crisis. The Sjavarklasinn (“Iceland Ocean Cluster”) network includes environmental entrepreneurs working across several industries.Thor Sigfusson founded the network in 2012 after conducting research on how partnerships between companies in Iceland’s technology sector helped expand that industry. At the time, he found that the fishing industry was not experiencing the same collaboration or growth.“Even though companies were in the same building together, fishing from the same quotas and facing similar challenges, they were closed off,” said Alexandra Leeper, the Iceland Ocean Cluster’s head of research and innovation.Three cod hanging on the wall of the second-floor entryway are the first thing to greet any visitor to the Iceland Ocean Cluster. Lightbulbs shine from their centers, and the dried scales filter the light to fill the space with an amber glow. The precise design is one that underlines the group’s belief that using 100 percent of a fish or natural resource can give rise to innovative technologies.Straddling the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, Iceland experiences dramatic seasons in an ever-changing geologic theater. Glaciers sit atop active volcano zones — the island exists in the extremes. This also means that Icelanders face daily indicators of climate change, such as increased glacial runoff.These visible impacts have given a heightened urgency to tackling environmental problems, fueling partnerships like the one between Encausse and Halldorsson.“It will all work out in the end,” Encausse says to a rain-drenched Algalif employee in passing as she and Halldorsson discuss the facility’s building timeline. In Icelandic, this is a common phrase — “þetta reddast” — that people use to assure one another.Learning to use all parts of a resourceEncausse and Marea co-founder Edda Bjork Bolladottir have partnered with the cluster for 2½ years. Encausse says that involvement was core to their company’s inception.“There is a collaborative mind-set when being on an island,” she said. “We need to work together to survive, and this was passed from generation to generation.”In a country about the size of Kentucky, the people of Iceland have had to learn how to guard their resources. Encausse has discovered that often means using 100 percent of any material — a lesson she’s now implementing in her work with Algalif. She created a food coating from Algalif’s leftover biomass, a product she’s named Iceborea — in a nod to the aurora borealis.“We are repurposing it and making something with value that gives it another life to avoid using more plastic,” Encausse said. Once Algalif’s factory expands over the next year, it will have 66 tons of microalgae leftovers that Encausse’s company can tap each year.When sprayed onto fresh produce, Iceborea becomes a natural thin film and a semipermeable barrier that can protect against microorganisms. Iceborea can either be eaten with produce or washed off, reducing the need for plastic packaging.Female founders in the clusterReusing factory byproducts is an entrepreneurial trend in Iceland.Take Edda Aradottir. She is the chief executive of Carbfix, a company capturing CO2 byproduct from the largest geothermal plant in Iceland, Hellisheidi, and injecting it into stone to be buried underground.Carbfix’s successful trials have marked a global milestone for carbon sequestration. It also has received international recognition — and Aradottir’s leadership has already served as a model for growing start-ups and other founders in the cluster trying to tackle extensive environmental concerns.“It’s inspiring to see that perseverance pays off,” Encausse said about Aradottir’s work.Another Icelandic company, GeoSilica, harvests silica buildup from the Hellisheidi waste stream to make health supplements. GeoSilica reaches the Icelandic and European markets, and its chief executive, Fida Abu Libdeh, is also working with the Philippines to pilot her silica-removal technology to create similar sustainable factory processes.A Palestinian from Jerusalem, Abu Libdeh moved to Iceland in 1995 at age 16, a transition she described as difficult because of the language barrier and the country’s small immigrant population. In 2012, she graduated from the University of Iceland after studying sustainable energy engineering and researching the health benefits of silica. That same year, she and Burkni Palsson co-founded GeoSilica.Ever since moving to Iceland, she was impressed with how the country produced electricity through geothermal sources.“I knew I was going to do something in connection with that in the future,” she said.GeoSilica is not formally part of the Iceland Ocean Cluster, but the network it has fostered reflects the same collaborative approach. Abu Libdeh has worked with cluster companies and held investor meetings at its headquarters. It’s a place that founders want to be, she said, where they want to learn from each other even if they are competitors in their fields.While there has been progress over the years, Abu Libdeh said, it’s still a challenge for women to enter this entrepreneurial space. In 2020, less than 1 percent of investment went to women-founded start-ups, according to a recent European Women in Venture Capital report.Halla Jonsdottir, research and development lead and co-founder of Optitog, has based her start-up in the cluster for three years. Her company is creating equipment to increase the catch area of shrimp trawls without scraping the seafloor — technology that’s meant to reduce fuel demands and CO2 emissions while protecting the ocean floor.As a female founder in the Icelandic fishing technology industry, Jonsdottir is a rarity. Leeper believes Jonsdottir may be one of the few women working in fishing gear innovation.Jonsdottir says the cluster helped drive her growth. “They put emphasis on making us visible in a male-driven industry.”Beyond IcelandWhat began as a dozen start-ups in 2012 has now grown to more than 70 members and associated firms connected to the Iceland Ocean Cluster. Sigfusson has ignited the blue economy within Iceland, but his project’s reach has also gone global.There are now four sister clusters in the United States, as well as one in Denmark and one in the Faroe Islands.The Alaska Ocean Cluster, which was the first to follow the Icelandic model, has already accelerated policy change in the United States. Sen. Lisa Murkowski (R-Alaska) proposed legislation last year to create “Ocean Innovation Clusters” in major U.S. port cities, which would provide grants along the U.S. coastline and the Great Lakes.“I’ve learned a great deal from our friends in Iceland who created a roadmap of innovation and public/private partnership when they established the first Oceans Cluster in Reykjavik,” Murkowski said in an email. “I’ll continue to press upon my colleagues the significance of this legislation and the promise it holds for the modernization and resilience of our maritime economy.”Back at the cluster houseAt 12:30 p.m. on a July afternoon, the cluster’s first-floor food hall, Grandi Matholl, buzzes during a busy hour. Fish haulers dressed in oversized, waterproof waders eat on wooden benches alongside employees in professional suits. Attached to the Matholl is Bakkaskemman, a seating area with a glass window where visitors can watch fish being unloaded off ships. Every afternoon on a business day, there’s an online auction to sell the day’s catch.Upstairs in her office, Jonsdottir works on her trawler technology. Later in the week, Encausse will use the meeting room space to meet with investors about Iceborea.The pungent smell of cod lingers in Bakkaskemman. It’s etched into the paint, leaking from the histories of the walls. In 30 minutes, the auction will begin.Sign up for the latest news about climate change, energy and the environment, delivered every Thursday

How microplastics are infiltrating the food you eat

Plastic pollution is one of the defining legacies of our modern way of life, but it is now so widespread it is even finding its way into fruit and vegetables as they grow.Microplastics have infiltrated every part of the planet. They have been found buried in Antarctic sea ice, within the guts of marine animals inhabiting the deepest ocean trenches, and in drinking water around the world. Plastic pollution has been found on beaches of remote, uninhabited islands and it shows up in sea water samples across the planet. One study estimated that there are around 24.4 trillion fragments of microplastics in the upper regions of the world’s oceans.

But they aren’t just ubiquitous in water – they are spread widely in soils on land too and can even end up in the food we eat. Unwittingly, we may be consuming tiny fragments of plastic with almost every bite we take.

In 2022, analysis by the Environmental Working Group, an environmental non-profit, found that sewage sludge has contaminated almost 20 million acres (80,937sq km) of US cropland with per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), often called “forever chemicals”, which are commonly found in plastic products and do not break down under normal environmental conditions.

Sewage sludge is the byproduct left behind after municipal wastewater is cleaned. As it is expensive to dispose of and rich in nutrients, sludge is commonly used as organic fertiliser in the US and Europe. In the latter, this is in part due to EU directives promoting a circular waste economy. An estimated 8-10 million tonnes of sewage sludge is produced in Europe each year, and roughly 40% of this is spread on farmland.

Due to this practice, European farmland could be the biggest global reservoir of microplastics, according to a study by researchers at Cardiff University. This means between 31,000 and 42,000 tonnes of microplastics, or 86 trillion to 710 trillion microplastic particles, contaminate European farmland each year.Spreading sewage sludge, or bio-solids, onto fields is common practice in many parts of the world (Credit: RJ Sangosti/The Denver Post/Getty Images)The researchers found that up to 650 million microplastic particles, measuring between 1mm and 5mm (0.04in-0.2in), entered one wastewater treatment plant in south Wales, in the UK, every day. All these particles ended up in the sewage sludge, making up roughly 1% of the total weight, rather than being released with the clean water.

The number of microplastics that end up on farmland “is probably an underestimation,” says Catherine Wilson, one of the study’s co-authors and deputy director of the Hydro-environmental Research Centre at Cardiff University. “Microplastics are everywhere and [often] so tiny that we can’t see them.”SENSORY OVERLOADFrom the microplastics sprayed on farmland to the noxious odours released by sewage plants and the noise harming marine life, pollutants are seeping into every aspect of our existence. Sensory Overload explores the impact of pollution on all our senses and the long-term harm it is inflicting on humans and the natural world. Read some of the other stories from the series here:

The underwater sounds that can kill

And microplastics can stay there for a long time too. One recent study by soil scientists at Philipps-University Marburg found microplastics up to 90cm (35in) below the surface on two agricultural fields where sewage sludge had last been applied 34 years ago. Ploughing also caused the plastic to spread into areas where the sludge had not been applied.

The microplastics’ concentration on farmland soils in Europe is similar to the amount found in ocean surface waters, says James Lofty, the lead author of the Cardiff study and a PhD research student at the Hydro-environmental Research Centre.

The UK has some of the highest concentrations of microplastics in Europe, with between 500 and 1,000 microplastic particles are spread on farmland there each year, according to Wilson and Lofty’s research.

As well as creating a large reservoir of microplastics on land, the practice of using sewage sludge as fertiliser is also exacerbating the plastics crisis in our oceans, adds Lofty. Eventually the microplastics will end up in waterways, as rain washes the top layer of soil into rivers or washes them into groundwater. “The major source of [plastic] contamination in our rivers and oceans is from runoff,” he says.

One study by researchers in Ontario, Canada, found that 99% of microplastics were transported away from where the sludge was initially dumped into aquatic environments.

Environmental contamination

Before they are washed away, however, microplastics can leach toxic chemicals into the soil. Not only are they made from potentially harmful chemicals that can be released into the environment as they break down, microplastics can also absorb other toxic substances, essentially allowing them to hitch a ride onto agricultural land where they can leach into the soil, according to Lofty.Tiny fragments of plastics – from clothing, cosmetics or larger plastics that break down – can get into water supplies and soil easily (Credit: Aris Messinis/AFP/Getty Images)A report by the UK’s Environment Agency, which was subsequently revealed by the environmental campaign group Greenpeace, found that sewage waste destined for English farmland was contaminated with pollutants including dioxins and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons at “levels that may present a risk to human health”.

A 2020 experiment by Kansas University agronomist Mary Beth Kirkham found that plastic serves as a vector for plant uptake of toxic chemicals such as cadmium. “In the plants where cadmium was in the soil with plastic, the wheat leaves had much, much more cadmium than in the plants that grew without plastic in the soil,” Kirkham said at the time.

Research also shows that microplastics can stunt the growth of earthworms and cause them to lose weight. The reasons for this weight loss aren’t fully understood, but one theory is that microplastics may obstructs earthworms’ digestive tracts, limiting their ability to absorb nutrients and so limiting their growth. This has a negative impact on the wider environment, too, the researchers say, as earthworms play a vital role in maintaining soil health. Their burrowing activity aerates the soil, prevents erosion, improves water drainage and recycles nutrients.

Plastic particles can also contaminate food crops directly. A 2020 study found microplastics and nanoplastics in fruit and vegetables sold by supermarkets and in produce sold by local sellers in Catania in Sicily, Italy. Apples were the most contaminated fruit, and carrots had the highest levels of microplastics among the sampled vegetables.

According to research by Willie Peijnenburg, professor of environmental toxicology and biodiversity at Leiden University in the Netherlands, crops absorb nanoplastic particles – minuscule fragments measuring between 1-100nm in size, or about 1,000 to 100 times smaller than a human blood cell – from surrounding water and soil through tiny cracks in their roots.

Analysis revealed that most of the plastics accumulated in the plant roots, with only a very small amount travelling up to the shoots. “Concentrations in the leaves are well below 1%,” says Peijnenburg. For leafy vegetables such as lettuces and cabbage, the concentrations of plastic would likely then be relatively low, but for root vegetables such as carrots, radishes and turnips, the risk of consuming microplastics would be greater, he warns.

Another study by Peijnenburg and his colleagues found that in both lettuce and wheat, the concentration of microplastics was 10 times lower than in the surrounding soil. “We found that only the smallest particles are taken up by the plants and the big ones are not,” says Peijnenburg.

This is reassuring, says Peijnenburg. However, many microplastics will slowly degrade and break down into nanoparticles, providing a “good source for plant uptake,” he adds.The uptake of the plastic particles did not seem to stunt the growth of the crops, according to Peijnenburg’s research. But what effect this accumulation of plastic in our food has on our own health is less clear.

Further research is needed to understand this, says Peijnenburg, especially as the problem will only get bigger.

“It will take decades before plastics are fully removed from the environment,” he says. “Even if the risk is currently not very high, it’s not a good idea to have persistent chemicals [on farmland]. They will pile up and then they might form a risk.”

Health impacts

While the impact of ingesting plastics on human health is not yet fully understood, there is already some research that suggests it could be harmful. Studies show that chemicals added during the production of plastics can disrupt the endocrine system and the hormones that regulate our growth and development.

Chemicals found in plastic have been linked to a range of other health problems including cancer, heart disease and poor foetal development. High levels of ingested microplastics may also cause cell damage which could lead to inflammation and allergic reactions, according to analysis by researchers at the University of Hull, in the UK.

The researchers reviewed 17 previous studies which looked at the toxicological impact of microplastics on human cells. The analysis compared the amount of microplastics that caused damage to cells in laboratory tests with the levels ingested by people through drinking water, seafood and salt. It found that the amounts being ingested approached those that could trigger cell death, but could also cause immune responses, including allergic reactions, damage to cell walls, and oxidative stress.

“Our research shows that we are ingesting microplastics at the levels consistent with harmful effects on cells, which are in many cases the initiating event for health effects,” says Evangelos Danopoulos, lead author of the study and a researcher at Hull York Medical School. “We know that microplastics can cross the barriers of cells and also break them, We know they can also cause oxidative stress on cells, which is the start of tissue damage.”Plastic fragments appear to accumulate most in the roots of plants, which is particularly problematic for tuber and root vegetables (Credit: Yuji Sakai/Getty Images)There are two theories as to how microplastics lead to cell breakdown, says Danopoulos. Their sharp edges could rupture the cell wall or the chemicals in the microplastics could damage the cell, he says. The study found that irregularly-shaped microplastics were the most likely to cause cell death.

“What we now need to understand is how many microplastics remain in our body and what kind of size and shape is able to cross the cell barrier,” says Danopoulos. If plastics were to accumulate to the levels at which they could become harmful over a period of time, this could pose an even greater risk to human health.

But even without these answers, Danopoulos questions whether more care is needed to ensure microplastics do not enter the food chain. “If we know that sludge is contaminated with microplastics and that plants have the ability to extract them from the soil, should we be using it as fertiliser?” he says.

Banning sewage sludge

Spreading sludge on farmland has been banned in the Netherlands since 1995. The country initially incinerated the sludge, but started exporting it to the UK, where it was used as fertiliser on farmland, after problems at an Amsterdam incineration plant.

Switzerland prohibited the use of sewage sludge as fertiliser in 2003 because it “comprises a whole range of harmful substances and pathogenic organisms produced by industry and private households”. The US state Maine also banned the practice in April 2022 after environmental authorities found high levels of PFAS on farmland soil, crops and water. High PFAS levels were also detected in farmers’ blood. The widespread contamination forced several farms to close.

The new Maine law also forbids sludge from being composted with other organic material.

But a total ban on using sewage sludge as fertiliser is not necessarily the best solution, says Cardiff University’s Wilson. Instead, it could incentivise farmers to use more synthetic nitrogen fertilisers, made from natural gas, she says.

“[With sewage sludge], we’re using a waste product in an efficient way, rather than producing endless fossil fuel fertilisers,” says Wilson. The organic waste in sludge also helps return carbon to the soil and enriches it with nutrients such as phosphorus and nitrogen, which prevents soil degradation, she says.”We need to quantify the microplastics in sewage sludge so that we can [determine] where the hot spots are and start managing it,” says Wilson. In places with high levels of microplastics, sewage sludge could be incinerated to generate energy instead of used as fertiliser, she suggests. One way to prevent the contamination of farmland is to recover fats, oil and grease (which contain high levels of microplastics) at wastewater treatment plants and use this “surface scum” as biofuel, instead of mixing it with sludge, Wilson and her colleagues say.

Some European countries, such as Italy and Greece, dispose of sewage sludge in landfill sites, the researchers note, but they warn that there is a risk of microplastics leaching into the environment from these sites and contaminating surrounding land and water bodies.

Both Wilson and Danopoulos say much more research is needed to quantify the amount of microplastics on farmland and the possible environmental and health impacts.

“Microplastics are now on the cusp of changing from a contaminant to a pollutant,” says Danopoulos. “A contaminant is something that is found where it shouldn’t be. Microplastics shouldn’t be in our water and soil. If we prove that [they have] adverse effects, that would make them a pollutant and [we] would have to bring in legislation and regulations.”

—

Join one million Future fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter or Instagram.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “The Essential List” – a handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife, Travel and Reel delivered to your inbox every Friday.

The steep cost of bio-based plastics

It’s the year 2050, and humanity has made huge progress in decarbonizing. That’s thanks in large part to the negligible price of solar and wind power, which was cratering even back in 2022. Yet the fossil fuel industry hasn’t just doubled down on making plastics from oil and gas — instead, as the World Economic Forum warned would happen, it has tripled production from 2016 levels. In 2050, humans are churning out trillions of pounds of plastic a year, and in the process emitting the greenhouse gas equivalent of over 600 coal-fired power plants. Three decades from now, we’ve stopped using so much oil and gas as fuel, yet way more of them as plastic.

Back here in 2022, people are trying to head off that nightmare scenario with a much-hyped concept called “bio-based plastics.” The backbones of traditional plastics are chains of carbon derived from fossil fuels. Bioplastics instead use carbon extracted from crops like corn or sugarcane, which is then mixed with other chemicals, like plasticizers, found in traditional plastics. Growing those plants pulls carbon out of the atmosphere and locks it inside the bioplastic — if it is used for a permanent purpose, like building materials, rather than single-use cups and bags.

This story was originally published by the Wired and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

At least, that’s the theory. In reality, bio-based plastics are problematic for a variety of reasons. It would take an astounding amount of land and water to grow enough plants to replace traditional plastics — plus energy is needed to produce and ship it all. Bioplastics can be loaded with the same toxic additives that make a plastic plastic, and still splinter into micro-sized bits that corrupt the land, sea, and air. And switching to bioplastics could give the industry an excuse to keep producing exponentially more polymers under the guise of “eco-friendliness,” when scientists and environmentalists agree that the only way to stop the crisis is to just stop producing so much damn plastic, whatever its source of carbon.

But let’s say there was a large-scale shift to bioplastics — what would that mean for future emissions? That’s what a new paper in the journal Nature set out to estimate, finding that if a slew of variables were to align — and that’s a very theoretical if — bioplastics could go carbon-negative.

The modeling considered four scenarios for how plastics production — and the life cycle of those products — might unfold through the year 2100, modeling even further out than those earlier predictions about production through 2050. The first scenario is a baseline, in which business continues as usual. The second adds a tax on CO2 emissions, which would make it more expensive to produce fossil-fuel plastics, encouraging a shift toward bio-based plastics and reducing emissions through the end of the century. (It would also incentivize using more renewable energy to produce plastic.) The third assumes the development of a more circular economy for plastics, making them more easily reused or recycled, reducing both emissions and demand. And the last scenario imagines a circular bio-economy, in which much more plastic has its roots in plants, and is used over and over.

“Here, we combine all of these: We have the CO2 price in place, we have circular economy strategies, but additionally we kind of push more biomass into the sector by giving it a certain subsidy,” says the study’s lead author, Paul Stegmann, who’s now at the Netherlands Organization for Applied Scientific Research but did the work while at Utrecht University, in cooperation with PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency. If all three conditions are met, he says, it is enough to push emissions into the negative.

It would take an astounding amount of land and water to grow enough plants to replace traditional plastics — plus energy is needed to produce and ship it all.

In this version of the future, people would still have to grow lots of crops to make bioplastics, but those plastics would be used — and reused — many times. “You basically put it into the system and keep it as long as possible,” says Stegmann.

To be clear, this is a hypothetical scenario, not a prediction for where the plastics industry is actually headed. Many pieces would have to fall together in just the right way for it to work. For one, Stegmann and his colleagues note in their paper, “a fully circular plastics sector will be impossible as long as plastic demand keeps growing.”

Plastics companies will happily meet that demand by ramping up production, says Steven Feit, senior attorney at the Center for International Environmental Law, which did the emissions report showing what would happen if plastics manufacturing grew through the year 2050. “The pivot to petrochemicals has been the plan for years now for the broader fossil fuel industry,” he says. “It’s understood that plastics, as well as nitrogen fertilizers, are the two real pillars of petrochemicals, which are the engine of growth for fossil fuels.”

And as long as the plastics industry keeps producing exponentially more of it, there’s no incentive to keep the stuff in circulation. It’s just so cheap to manufacture, which is why recycling straight-up doesn’t work in its current form. (Among the many reasons why scientists are calling for negotiators of a new treaty to add a cap on production is that it would increase the price and demand for recycled plastic.) Another wrinkle is that plastic can only be recycled once or twice before it becomes too degraded. Some products, like multilayered pouches, have become increasingly complicated to recycle, so wealthy nations have been shipping them all to economically developing countries to deal with. Which is about as far from a circular economy as you can get.

Another issue is the space needed to grow the feedstock crops. “It increases the already huge pressure on land use,” says Jānis Brizga, an environmental economist at the University of Latvia, who studies bio-based plastics but wasn’t involved in the new paper. “Land use change has been one of the main drivers for biodiversity loss — we’re just pushing out all the other species.”

In 2020, Brizga published a paper calculating how much land it would take to grow enough plants for bioplastics to replace all the traditional plastics used in packaging. The answer: At a minimum, an area bigger than France, requiring 60 percent more water than the European Union’s annual freshwater withdrawal. (The new paper did model some land-use considerations, like restricting where biomass could be grown, but Stegmann says that a better understanding of the implications of this biomass growth is an avenue for future research.)

It would also take a whole lot of chemicals to keep those plants healthy. “Many of these crops are produced in intensive agricultural systems that use a lot of pesticides and herbicides and synthetic chemicals,” Brizga says. “Most of them are also very, very dependent on fossil fuels.”

And from a human health perspective, we don’t even want to keep plastics circulating around us. A growing body of evidence links their component chemicals to health problems: One study linked phthalates (a plasticizer chemical) to 100,000 early deaths each year in the U.S., and the researchers were being conservative with that estimate. Microplastics are showing up in people’s blood, breast milk, lungs, guts, and even newborns’ first feces, because we’re absolutely surrounded by plastic products — clothing, carpeting, couches, bottles, bags.

It’s also not clear what kind of climate effect the plastics will have after they’re produced. Early research on microplastics suggests that they release significant amounts of methane — an extremely potent greenhouse gas — as they break down in the environment. Even if a circular bioplastics economy attempts to keep carbon and methane locked up by turning plastics into long-term building materials or landfilling whatever can’t be used again, nobody knows for sure if it will work. We need more research on how plastics off-gas their carbon under different conditions.

The more plastic we produce, the more corrupted the environment grows — it’s already poisoning organisms and destabilizing ecosystems. “I fear that by the time we get enough answers to all of our questions, it will be too late,” says Kim Warner, senior scientist at the advocacy group Oceana, who wasn’t involved in the new paper. “The train will have already left the station, for what it’s doing to the atmosphere and the oceans and carbon and health and everything else.”

Matt Simon is a science journalist at Wired.

Apocalyptic highway fire exposes dangers of plastic tunnels

Automobiles on Friday burned in fire that broke out in a noise-barrier tunnel on the Second Gyeongin Expressway, which connects Incheon to Seongnam [YONHAP] An apocalyptic conflagration left a stretch of highway near Seoul a mess of molten plastic and melted cars. And it left relatives of the victims — the dead now numbering five — in utter disbelief. “It can’t be your dad,” a woman sobbed at a hospital with her daughters after hearing that her husband is one of the deceased. The fire broke out Thursday afternoon at the North Uiwang Interchange on the Second Gyeongin Expressway, also known as highway 110, which runs south of Seoul from Incheon toward the east and into the center of the country. According to investigators, a burning garbage truck ignited the plastic, translucent material of a noise-barrier tunnel that covered the elevated highway, and that 830-meter (2,723-foot) tunnel burst into flames, trapping cars and people in their cars. In addition to the five dead, 41 were injured and three remain in critical condition. The woman’s 66-year-old husband cannot be identified with certainty, and DNA testing will have to be done. The family was told the tests will be completed in a day or two. “Who should we blame?” she asked as she cried over her husband’s death. “Is this the fault of the truck driver?” The victim worked as a personal driver, a friend said. Before he was found dead, he called his boss and said he was inhaling smoke at the scene. “He really wanted to become a taxi driver,” the friend recalled. Cho Nam-seok, 59, who was at the accident site recalls hearing a loud thud after he barely escaped from his melting car. “A friend I was with in the car was not able to get out,” Cho said. His head is wrapped with bandages, and the back of his hand and left ear are severely burned. The plastic material that formed the wall of the tunnel is being blamed. According to officials, the tunnel was made of polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA), commonly known as acrylic. The noise-barrier tunnels in Korea are usually made out of PMMA, polycarbonate or glass, with PMMA being used most due to its low price. In terms of safety, it is the worst, according to experts. Compared to other materials, PMMA is easily ignited, melts quickly and tends to continue burning, according to a report from Korea Expressway Corporation in 2018. As the fire spread to the tunnel, the acrylic material melted and fell on the road and vehicles, which would have accelerated the fire. “As the public and the press have pointed out, the material of the noise-barrier tunnel seems to be the major issue of the accident,” said Minister of Land, Infrastructure and Land Won Hee-ryong after he visited the accident site on Friday morning. “Concerns on about PMMA material for being flammable have always been made by experts.” A total of 55 noise-barrier tunnels in Korea are to be fully inspected, while those still under construction will be finished with safer materials. Police started a full-scale investigation of the accident on Friday. The Gyeonggi Nambu Provincial Police Agency brought the garbage truck driver in for questioning on the possible charge of involuntary manslaughter. The driver reportedly said a fire broke out in his truck following the sound of an explosion. Authorities have blocked off 20 kilometers of the expressway. BY KIM JUNG-MIN, SON SUNG-BAE, KIM HONG-BUM, CHO JUNG-WOO [cho.jungwoo1@joongang.co.kr]