Before the tiny Greek island of Tilos became a big name in recycling, taverna owner Aristoteles Chatzifountas knew that whenever he threw his restaurant’s trash into a municipal bin down the street it would end up in the local landfill.The garbage site had become a growing blight on the island of now 500 inhabitants, off Greece’s south coast, since ships started bringing over packaged goods from neighboring islands in 1960.Six decades later, in December last year, the island launched a major campaign to fix its pollution problem. Now it recycles up to 86 percent of its rubbish, a record high in Greece, according to authorities, and the landfill is shut.Chatzifountas said it took only a month to get used to separating his trash into three bins — one for organic matter; the other for paper, plastic, aluminium and glass; and the third for everything else.“The closing of the landfill was the right solution,” he told the Thomson Reuters Foundation. “We need a permanent and more ecological answer.”Tilos’ triumph over trash puts it ahead in an inter-island race of sorts, as Greece plays catch-up to meet stringent recycling goals set by the European Union (EU) and as institutions, companies and governments around the world adopt zero-waste policies in efforts to curb greenhouse gas emissions.“We know how to win races,” said Tilos’ deputy mayor Spyros Aliferis. “But it’s not a sprint. This is the first step (and) it’s not easy.”The island’s performance contrasts with that of Greece at large. In 2019, the country recycled and composted only a fifth of its municipal waste, placing it 24th among 27 countries ranked by the EU’s statistics office.That’s a far cry from EU targets to recycle or prepare for reuse 55 percent of municipal waste by weight by 2025 and 65 percent by 2035.Greece has taken some steps against throwaway culture, such as making stores charge customers for single-use plastic bags.Still, “we are quite backward when it comes to recycling and reusing here,” said Dimitrios Komilis, a professor of solid waste management at the Democritus University of Thrace, in northern Greece.Recycling can lower planet-warming emissions by reducing the need to manufacture new products with raw materials, whose extraction is carbon-heavy, Komilis added.Workers sort through municipal waste at a Polygreen factory located on the island of Tilos, Greece, on June 30, 2022. Credit: Thomson Reuters Foundation / Sebastien MaloGetting rid of landfills can also slow the release of methane, another potent greenhouse gas produced when organic materials like food and vegetation are buried in landfills and rot in low-oxygen conditions.And green groups note that zero-waste schemes can generate more jobs than landfill disposal or incineration as collecting, sorting and recycling trash is more labor-intensive.But reaching zero waste isn’t as simple as following Tilos’ lead — each region or city generates and handles rubbish differently, said researcher Dominik Noll, who works on sustainable island transitions at Vienna’s Institute of Social Ecology.“Technical solutions can be up-scaled, but socioeconomic and sociocultural contexts are always different,” he said.“Every project or program needs to pay attention to these contexts in order to implement solutions for waste reduction and treatment.”High-value trashTilos has built a reputation as a testing ground for Greece’s green ambitions, becoming the first Greek island to ban hunting in 1993 and, in 2018, becoming one of the first islands in the Mediterranean to run mainly on wind and solar power.For its “Just Go Zero” project, the island teamed up with Polygreen, a Piraeus-based network of companies promoting a circular economy, which aims to design waste and pollution out of supply chains.Several times a week, Polygreen sends a dozen or so local workers door-to-door collecting household and business waste, which they then sort manually.Antonis Mavropoulos, a consultant who designed Polygreen’s operation, said the “secret” to successful recycling is to maximize the waste’s market value.“The more you separate, the more valuable the materials are,” he said, explaining that waste collected in Tilos is sold to recycling companies in Athens.On a June morning, workers bustled around the floor of Polygreen’s recycling facility, perched next to the defunct landfill in Tilos’ arid mountains.They swiftly separated a colorful assortment of garbage into 25 streams — from used vegetable oil, destined to become biodiesel, to cigarette butts, which are taken apart to be composted or turned into materials like sound insulation.Organic waste is composted. But some trash, like medical masks or used napkins, cannot be recycled, so Polygreen shreds it, to be turned into solid recovered fuel for the cement industry on the mainland.More than 100 tons of municipal solid waste — the equivalent weight of nearly 15 large African elephants — have been sorted so far, said project manager Daphne Mantziou.Crushed by negative news? Sign up for the Reasons to be Cheerful newsletter.Setting up the project cost less than 250,000 euros ($255,850) — and, according to Polygreen figures, running it does not exceed the combined cost of a regular municipal waste-management operation and the new tax of 20 euros per ton of landfilled waste that Greece introduced in January.More than ten Greek municipalities and some small countries have expressed interest in duplicating the project, said company spokesperson Elli Panagiotopoulou, who declined to give details.No time to wasteReplicating Tilos’ success on a larger scale could prove tricky, said Noll, the sustainability researcher.Big cities may have the money and infrastructure to efficiently handle their waste, but enlisting key officials and millions of households is a tougher undertaking, he said.“It’s simply easier to engage with people on a more personal level in a smaller-sized municipality,” said Noll.When the island of Paros, about 200 km (124 miles) northwest of Tilos, decided to clean up its act, it took on a city-sized challenge, said Zana Kontomanoli, who leads the Clean Blue Paros initiative run by Common Seas, a UK-based social enterprise.The island’s population of about 12,000 swells during the tourist season when hundreds of thousands of visitors drive a 5,000 percent spike in waste, including 4.5 million plastic bottles annually, said Kontomanoli.In response, Common Seas launched an island-wide campaign in 2019 to curb the consumption of bottled water, one of a number of its anti-plastic pollution projects.Using street banners and on-screen messages on ferries, the idea was to dispel the common but mistaken belief that the local water is non-potable.The share of visitors who think they can’t drink the island’s tap water has since dropped from 100 percent to 33 percent, said Kontomanoli.“If we can avoid those plastic bottles coming to the island altogether, we feel it’s a better solution” than recycling them, she said.Another anti-waste group thinking big is the nonprofit DAFNI Network of Sustainable Greek Islands, which has been sending workers in electric vehicles to collect trash for recycling and reuse on Kythnos island since last summer.Project manager Despina Bakogianni said this was once billed as “the largest technological innovation project ever implemented on a Greek island” — but the race to zero waste is now heating up, and already there are more ambitious plans in the works.Those include CircularGreece, a new 16-million-euro initiative DAFNI joined along with five Greek islands and several mainland areas, such as Athens, all aiming to reuse and recycle more and boost renewable energy use.“That will be the biggest circular economy project in Greece,” said Bakogianni

Category Archives: Land

Pika wants to makes cleaning reusable diapers as easy as throwing out disposable ones

Babies use 6,500 disposable diapers before they’re potty trained, and cloth diapers are labor intensive to clean. Pika hopes to eliminate both that waste, and all that work.

[Photo: courtesy Pika]

By

Collision course: Will the plastics treaty slow the plastics rush?

The interlacing pipelines of a massive new plastics facility gleam in the sunshine beside the rolling waters of the Ohio River. I’m sitting on a hilltop above it, among poplars and birdsongs in rural Beaver County, Pennsylvania, 30 miles north of Pittsburgh. The area has experienced tremendous change over the past few years — with more soon to come.

The ethane “cracker plant” belongs to Royal Dutch Shell, and after 10 years and $6 billion it’s about to go online. Soon it will transform a steady flow of fracked Marcellus gas into billions of plastic pellets — a projected 1.6 million tons of them per year, each the size of a pea. From this northern Appalachia birthplace, they’ll travel the globe to make the plastic goods of modern life, from single-use bags to longer-lasting sports equipment.

The factory. Photo: Tim Lydon

The plant’s construction has lifted a hardscrabble local economy, but it also embodies an epic global struggle.

Earlier this year and half a world away, United Nations negotiators meeting in Kenya pledged to draft a legally binding international plastics treaty by 2024. Many hope it will cap global plastics production while also addressing plastic’s impacts on environments and people. When treaty talks begin later this year, they’ll have everything to do with plants like this one and hundreds like it popping up around the world.

But the plants, and their powerful backers in the plastics and fossil fuel industries, will also shape the talks.

“They will work very hard to make sure that the treaty is not effective,” says Judith Enck, former EPA regional administrator in the Northeast and president of Beyond Plastics, a nonprofit that seeks to stem plastics pollution.

Enck describes plastics as a “Plan B” for fossil fuels, at a time when renewables and efficiency erode industry profits. To Shell and its peers, plastics production can secure assets like Pennsylvania’s seemingly bottomless Marcellus gas field, which might otherwise go untapped as the world retreats from fossils in the face of climate change.

Plastic waste collects in a drainage ditch in 2021. Photo: Ivan Radic (CC BY 2.0)

But Enck notes that plastics also drive climate change. A 2021 Beyond Plastics report estimated that U.S. plastics production now puts out heat-trapping emissions equivalent to 116 coal-fired power plants. With more facilities like the one in Pennsylvania coming, the report says, U.S. plastics could exceed the climate impact of domestic coal-fired energy by 2030.

The International Panel on Climate Change and others echo the concern, saying that global plastics production could reach 20% of oil consumption in the coming decades, surpassing concrete, food waste, and other heavy heaters. Today the United States, China, Saudi Arabia and Japan lead the trend as the world’s top producers of plastic.

Waste is another concern. With little plastic ever recycled, it’s now found from the deepest oceans to the highest mountains. One estimate has its volume in marine waters surpassing that of fish by mid-century. And while images of plastics in the bellies of birds, fish and whales have become old news, new research shows microplastics ingested by trees, deposited on Arctic sea ice, and entering the developing brains of human babies.

Plastic waste also emits greenhouse gases as it breaks down or when it’s incinerated.

Enck also calls it an environmental justice issue, with plastics production and disposal disproportionately impacting poorer communities.

But Enck sees rising awareness, too.

“I have met climate change skeptics, but I have never met a plastic pollution skeptic,” she says. People see the problem firsthand and want governments to act.

To her, one solution to the crisis is a binding international treaty that addresses plastics production, use and disposal.

My hilltop perch sits near new townhomes, and residents of the community come and go. They include two older men who grew up nearby and have come to release happy birthday balloons, which they then watch fade into blue sky through binoculars.

Around the same time Jeff Coleman, candidate for lieutenant governor, arrives with local officials to film a campaign spot. They discuss “downstream” manufacturers that could spring up near the plant, which itself will soon employ 600 people.

Below us the plant dominates the landscape. Neatly squeezed onto 400 acres, it hosts its own gas power plant, a string of cylindrical polyethylene reactors, and miles of convoluted pipeline, along with warehouses, offices and room for more than 3,000 railcars to shuttle the tiny pellets away.

To build it, Shell remediated an old zinc smelter, redirected a local highway, built a railroad spur and laid the 97-mile Falcon Ethane Pipeline to access nearby Marcellus gas. During construction, more than 8,000 workers clocked in every day.

Land clearing at the Shell site in 2016. Photo (uncredited) via Gov. Tom Wolf/Flickr (CC BY 2.0)

“It put our county on the map,” says Beaver County commissioner Jack Manning.

He says construction sustained pandemic-strapped businesses and attracted investment in hotels, malls and even housing, like the new townhomes overlooking the plant. Manning also expects years of both direct and indirect job creation.

For many community leaders of this one-time manufacturing epicenter, which has struggled since steel moved away in the 1980s, these are welcome developments.

But others counter Manning’s rosy assessments, pointing to continued economic stagnation in the region since construction began. Still, state and local governments have bet big on Shell by awarding it the largest corporate tax break in Pennsylvania history.

The government support matters. In the United States and other countries that will soon negotiate the global plastics treaty, local investment translates into political power for plastics. That was clear when then-President Trump gave a 2019 campaign-style speech at the Shell plant, touting his commitment to U.S. manufacturing.

Manning says that behind such support are real benefits for the community, including the young families he sees buying townhomes and reinvigorating local communities.

As for environmental effects, Manning, who spent 35 years in the petrochemical industry, believes Shell’s state-of-the-art technology will protect local air and waters. He shares activists’ broader concerns about climate change and ocean pollution, but says the pellets made here will create products that improve lives, such as replacement knee joints, lightweight parts for electric cars and packaging that prevents food spoilage.

And he’s confident a global plastics treaty won’t hurt locally. If anything, global initiatives to reduce plastic production could secure demand from existing plants by limiting the construction of new ones, he says.

Jace Tunnell of the University of Texas Marine Science Institute offers another take.

In 2018 Tunnell discovered plastic pellets — called nurdles in the plastic-waste world — washed up on local beaches. When he learned they came from nearby plastics facilities, he created the nonprofit Nurdle Patrol to enlist citizens in monitoring pellet pollution along the Gulf of Mexico. The work is raising awareness and contributing to stricter permitting rules.

Nurdles and other plastic waste at a beach cleanup event. Photo: Hillary Daniels (CC BY 2.0)

Groups in Beaver County have since taken similar action to gather baseline environmental data before the Shell plant goes online.

“I haven’t seen a facility yet where there aren’t pellets in the environment,” says Tunnell. Their small size enables dispersal by wind, rain, storm drains and the pneumatic equipment that blows them onto railcars at production facilities. They can also wind up along railroad routes, at shipyards and in the ocean, depending on shipping practices.

Tunnell offers the example of former Gulf of Mexico shrimper Diane Wilson, who in 2019 won a $50 million settlement from a Formosa plastics facility in Texas that discharged billions of pellets and other pollutants.

And he points to a 2021 Sri Lankan cargo ship disaster that left beaches knee-deep in nurdles.

“They’re still cleaning them up,” he says.

Events like that have contributed to a tide of negative press that — along with inflation, the pandemic and other factors — have slowed the plastics boom. That’s evident in Pennsylvania. Only a few years ago, plastics makers had sketched out five new plants for the region to tie into Marcellus gas, plus two ethane-storage facilities. But three plants are now canceled, and neither storage facility has been built.

Governmental pushback, including momentum toward a global treaty, is also mounting, as seen by China’s 2017 decision to stop importing plastic waste for recycling. That policy change stranded plastic waste in U.S. communities and has contributed to federal and state efforts to hold retailers of single-use plastics accountable for the waste, something the European Union achieved in 2021.

For its part, the plastics industry claims a positive economic impact and commitments to environmental safety, which include its voluntary Operation Clean Sweep, designed to minimize pellet pollution. Shell representatives in Pennsylvania did not respond to interview requests but cited their participation in Clean Sweep and directed questions to their website, which describes mitigations for noise, air pollution and other plastics production issues.

But for Enck, industry-led initiatives fall short. She believes they distract from climate, equity, and other broader problems that she hopes are addressed in upcoming treaty talks.

As the treaty framework came together last February, industry allies pushed for an emphasis on waste management, including mitigating marine debris and improving recycling, which remains technologically difficult.

But delegates from Rwanda and Peru successfully advanced a more ambitious resolution that will consider the full life cycle of plastics, including production, disposal and its pollution impact on all environments, not just oceans. The resolution’s inclusion of a possible cap on virgin plastics production was supported by letters from international scientists and corporations such as Walmart and Coca-Cola.

In March delegates from 175 counties approved the Rwanda-Peru framework. Procedures and timelines were established at June meetings in Senegal, and negotiations are slated to begin in Uruguay in November. Although a treaty is expected in 2024, its true effect will depend on ratification from the United States and other top plastics producers and whether member nations will adhere to it.

In the meantime, political and market forces will continue determining how many more facilities like Pennsylvania’s Shell plant are built.

As I leave my Beaver County hillside, I ask the two men what will become of the balloons they’re releasing. They look at me for a moment, then one tells me with a shrug that they’ll eventually explode and fall to the ground.

That reminds me of something Enck said: “We’re leaving a mess for future generations.”

Get more from The Revelator. Subscribe to our newsletter, or follow us on Facebook and Twitter.

How to Turn Off the Tap on Plastic Waste

Environmentalists say policies limiting single-use plastics are necessary to curb North Carolina's growing microplastics problem

By Will Atwater

An environmental advocacy group in Durham has been pushing for a county-wide proposal to put a 10-cent fee on single-use plastic bags. Activists across the state have been eagerly watching to see if Durham’s local government officials will move forward on what would be the only policy on the books in North Carolina aimed at preventing plastic waste from entering the environment.

Advocates had hoped to see the issue discussed at a Durham Joint City-County Committee meeting on Tuesday, but due to a technical issue, it seems the bag fee proposal will be pushed off to a later date. Meanwhile, environmentalists say these are the kinds of policies needed statewide to combat the ever-growing microplastic waste problem.

“We have to all work together, but I’m sick of just the continual focus on mitigation. Can we please also spend equal energy on prevention?” said Crystal Dreisbach, founder of Don’t Waste Durham, the nonprofit organization behind the bag fee proposal which works to prevent trash at the source.

The bag fee proposal in Durham is the kind of policy advocates at Waterkeepers Carolina, a nonprofit aimed at preserving the state’s waterways, say would be really helpful. The waterkeepers are in a downstream-battle to capture a constant flow of plastic waste before it enters the ocean. And they’re losing.

The amount of plastic waste entering North Carolina’s waterways and soil is outpacing their capacity to remove it.

“The only way we’re going to make any kind of headway with this type of pollution problem is prevention, prevention, prevention,” said Lisa Rider, director of Coastal Carolina Riverwatch.

“And policies are certainly at the top of the hierarchy in doing so.”

Don’t waste Durham’s plan

In 2021, Duke Environmental Law and Policy Clinic developed the proposed 10-cent bag fee on behalf of the local nonprofit Don’t Waste Durham. A white paper produced by the law clinic and published on the nonprofit’s website states that while customers are given free plastic or paper bags at check-out counters, there are significant costs associated with using these materials.

“These bags have very real costs for our community: they contribute to litter on streets and in waterways, clog storm drains, take unlimited landfill space, and wreak havoc on recycling infrastructure.”

The white paper also claims that it costs Durham more than $86,000 per year in related fees.

In drafting the plan, Dreisbach wanted to make sure the proposed ordinance did not penalize low-income residents. Durham shoppers who are on an assistance program, such as WIC or SNAP, would be exempt from the bag fee, she explained.

Don’t Waste Durham also supports an initiative called Bull City Boomerang Bag whose mission is to assist communities in “tackling waste at its source.” Durham businesses such as Part & Parcel, Durham Co-op Market and Pennies for Change are some shops that offer free Bull City Boomerang Bags to their customers. A volunteer staff uses donated fabric to make the bags, which are then given away.

South Florida's baby sea turtles are threatened by plastic and light pollution

The sun has yet to peek its way through the clouds on this windy, rainy morning as I ride along the shoreline in a UTV at Red Reef Park in Boca Raton with David Anderson, the sea turtle conservation coordinator for the Gumbo Limbo Nature Center.Anderson and his crew come here every morning between March and October to survey sea turtle nesting and hatching activity along this 5-mile stretch of beach.“So leatherback, loggerhead and green sea turtles all make different looking tracks in the sand and it’s pretty easy to discern actually,” Anderson said.WLRN is here for you, even when life is unpredictable. Our journalists are continuing to work hard to keep you informed across South Florida. Please support this vital work. Become a WLRN member today. Thank you.We follow the tracks to a small dip in the sand. Anderson tells me a loggerhead laid her eggs here last night. He marked the nest by surrounding the perimeter with orange wooden stakes and tape, then labeled it with today’s date.“This turtle nest hatched,” Anderson said. “We give each nest three days or 72 hours for the hatchlings to get out on their own. And then we come back and excavate the site.”

Yvonne Bertucci zum Tobel

/

WLRN A baby loggerhead sea turtle was found while excavating a nest.

While digging out the nest with his hand, Anderson finds a live baby loggerhead.“The purpose of us excavating nests is to evaluate the hatch success of the nest and see how successful our nests are here on the beach but the bonus is we often find live baby turtles in the nest and those get a second chance,” Anderson said.This baby turtle will get its second chance tonight — at a hatchling release organized by the nature center. Tickets were sold out months in advance.Cerridwen Canens lives near Orlando. She bought her ticket in May.“It’s been a lifelong dream of mine, I’ve always wanted to do this so it’s pretty special to have the opportunity. I’m pretty happy,” she said.Before the hatchlings are released, I join 18 other guests in a classroom at Gumbo Limbo Nature Center. The 20-acre property in Boca Raton has been promoting sea turtle awareness since 1984, through environmental conservation, research and education.During the presentation, Anderson tells us about the three types of sea turtles they find along their beaches — green, loggerhead and leatherback. Anderson says to stay away from single-use plastics. Microplastics make their way into the ocean and get stuck in sargassum seaweed, where baby turtles take shelter for the first several years of their lives. The seaweed provides food and camouflages them from predators.“Hatchlings, when they go offshore, are very opportunistic feeders,” Anderson said. “They’ll pretty much eat anything in front of their face that looks appetizing, that looks delicious. And you can imagine a tiny, colorful piece of plastic in front of them they will consume. They will also consume plastic bags or shopping bags because those floating in the ocean look like what? Jellyfish.”Once hatchlings make it to the ocean, they swim 15 miles offshore until they reach the sargassum seaweed mats.Every single hatchling Anderson and his crew find washed up along the shore has plastic in its belly.

Yvonne Bertucci zum Tobel

/

WLRNArtificial light pollution from cities confuses baby sea turtles. This photo was taken at Red Reef Park looking north. The ocean is on the right (east) and the light is coming from above the dunes to the west.

For millions of years, hatchlings have crawled toward the ocean. But that’s changed. Florida’s growing coastal population means more artificial light at night. Many cities and residents opt for LED lighting, because it’s more cost effective. But the light is so bright to a sea turtle, that it can seem like the ocean’s horizon.“It’s more difficult to address the bigger problem, which is artificial light pollution from inland, because you go out on the beach at night and you see this massive glow in the sky and unfortunately, sea turtle hatchlings are attracted to that glow because they think that is the horizon over the ocean,” Anderson said.In Boca Raton, there are lighting ordinances along A1A, but less than one-fourth of a mile from the beach, street lights brighten the night sky. Anderson said cities and homeowners should use amber-hued light bulbs and lighting fixtures that point down, not up into the sky.At 9:30 that night, we make our way out to the beach … the 180 active sea turtles they gathered that morning are in buckets.

Photo courtesy of the Gumbo Limbo Nature Center

/

A nighttime hatchling release organized by the Gumbo Limbo Nature Center.

We approach the shoreline and release the hatchlings. Only one in a thousand of these babies will make it to adulthood.Cerridwen Canens is standing at the shoreline, the waves washing up against her legs. She looks out into the ocean and tells me she’ll be coming back again next year.“It’s like that really ancient connection to a part of myself that’s lived you know, a thousand lifetimes and it’s the closest feeling I can describe to home really, I just, I needed this, it was really a very special experience,” she said.

Yvonne Bertucci zum Tobel

/

WLRNOnce excavated from the nest, the baby sea turtles are placed in a bucket for release later that night.

‘Spiderwebs’ to the rescue for Indonesia’s coral reefs

A small-scale project in Indonesia is seeing success in efforts to restore coral reefs damaged by blast fishing.Lightweight cast-iron rods form underwater “spiderwebs” that are placed onto existing reefs, with new coral grafted onto the structure.Proponents of the project say the benefits are already tangible, but add that to make them last, there needs to be an end to destructive fishing practices. Ultra-strong fibers, multi-legged robots, pain relievers — all are human innovations inspired by spiders.

Now, conservationists in Indonesia are rehabilitating coral reefs using what’s known as the coral spider technique.

The method is a type of reef restoration project involving the installation of man-made “spiderwebs” onto which new corals are grafted. It entails placing small, lightweight rods “made from cast iron that is welded into a hexagonal shape, like a spider web,” Imam Fauzi, head of the National Aquatic Conservation Center (BKKPN) in Kupang, a port city on the island of Timor where one such project is underway, told Mongabay.

Indonesia has one of the most extensive coral reef systems in the world, but more than a third is in poor condition, according to a 2018 study. Much of the damage is due to warming oceans, blast fishing, plastic pollution, and severe storms.

Clean-up day at Oesina Beach, West Kupang, Indonesia. Image by BKKPN Kupang.

The spider technique was previously deployed in Indonesia under a project backed by food giant Mars in which thousands of “coral spiders” were installed off the islands of Sulawesi and Bali.

At Oesina Beach in Kupang Bay, conservationists are installing spider frames. The six-sided structures have three top beams spanning 54 centimeters (21 inches) each and six 36-cm (14-in) side beams. The frame is latched onto the reef with plastic cable ties.

The practice is low cost, materials are readily available, construction is easy, and getting the material to the rehabilitation location doesn’t require great effort, Imam said.

“On average, transplanted coral with this method can grow well if maintenance and cleaning are routinely conducted,” he said.

BKKPN Kupang started using the spider technique in 2019 on the islands of Sabu (Sawu) and Raijua, west of Timor. Within its work scope, the center has done rehabilitation jobs in the provinces of West Nusa Tenggara, South Sulawesi, Maluku and Papua.

Rehabilitation of coral reefs in commemoration of Coral Triangle Day 2022 in Oesina Beach. Image by BKKPN Kupang.

Currently, BKKPN Kupang is teaming up with two locally based units of national companies and YAPEKA, a conservation nonprofit, to rehabilitate the coral reefs of Oesina Beach. The damage there is due to blast fishing and poison fishing, Imam said.

The center has placed 150 spiderweb units covering 150 square meters (about 1,600 square feet) of reef, he said.

YAPEKA began work in Kupang Bay in October 2021 after Tropical Cyclone Seroja hit the area in April that year. The NGO started with 700 finger-long coral fragments secured by 50 spiderweb units covering a 0.2-hectare (0.5-acre) expanse. It has now expanded to 0.4-0.6 hectares (1-1.5 acres).

YAPEKA has installed 200 spiderweb units in one location in collaboration with PLN, the state-owned electricity company, which operates a coal-fired power plant in the bay area.

“If it evolves well, in three or four years it can become a coral garden allowing for underwater tourism and a source for adopting coral fragments for other locations [needing rehabilitation],” YAPEKA East Nusa Tenggara field coordinator Fredik Ngili told Mongabay.

Children take part in a clean up event in commemmoration of Coral Triangle Day. Image by BKKPN Kupang.

YAPEKA has also set up an ecotourism information center on the beach, where tour guides are trained.

The coral garden area can be enlarged beyond Oesina Beach to cover other locations in the waters of Kupang Bay, Fredik said. He emphasized the need for community education on using environmentally friendly fishing gear as a way to preserve healthy coral reefs. There should also be an end to littering in the sea, especially plastic waste, and a campaign to spread the message about the benefits and functions of coral reefs, he added.

Imam agreed, adding that people shouldn’t overuse the benefit of coral reefs. He also called for safeguarding the health and quality of the water. He said boats shouldn’t drop anchor in coral reef zones and spiderweb units shouldn’t be installed on living coral.

Among the beneficiaries of the coral reef rehabilitation efforts are the inhabitants of Lifuleo village by the beach. “Fish development has increased income,” village head Zwingli Say told Mongabay.

Banner image: Rehabilitation of coral reefs in commemoration of Coral Triangle Day 2022 in Oesina Beach. Image by BKKPN Kupang.

A version of this story was reported by Mongabay’s Indonesia team and first published here on our Indonesian site on June 14, 2022.

Biodiversity, Community-based Conservation, Conservation, Coral Reefs, Ecological Restoration, Environment, Fish, Fishing, Habitat Destruction, Innovation In Conservation, Marine, Marine Conservation, Marine Ecosystems, Oceans, Overfishing, Restoration, Saltwater Fish

Print

This company is turning plastic trash into construction blocks

Imagine taking heaps and heaps of earth-polluting, unusable plastic waste and actually transforming it into something constructive?Plastic pollution is a proliferating and increasingly overwhelming problem. By 2040, estimates indicate that as much as 710 million tons of solid plastic waste will clog up the earth’s ecosystem, in oceans, rivers and on land.Los Angeles-based startup ByFusion has a plan for that waste. In fact, the business has created a system to collect the most troublesome type of plastic trash — the stuff that can’t be recycled.Founded in 2017, the company has developed a machine that turns single-use plastics into something called “ByBlock.” Similar in size and shape to the concrete blocks commonly used in construction, ByBlocks are made entirely of reclaimed plastic waste.”You’d be astounded at the things that cannot be recycled, which is basically everything you touch … stuff like pens, toothbrushes,” ByFusion’s CEO, Heidi Kujawa, told CNN Business. “The interesting thing about our technology is we specifically, entirely designed our system around the low value, no value stuff, everything that can’t be recycled.”As she researched plastic waste, Kujawa learned that there are seven types of plastic, of which only two can be recycled. “In the past it used to go to China and other places that would buy it from us,” she said. “That dried up in 2017. Since then, we’ve been burning or burying that plastic.”ByFusion’s machine, called the Blocker System, converts the discarded waste into building blocks without having to sort or pre-wash them, a major obstacle in the plastic recycling process.After collecting the waste, it takes only minutes to shred the plastic is shredded and fuse it into solid blocks using steam and compression. The blocks are made without additives or fillers — 22 pounds of plastic create 22 pounds of ByBlock bricks.”We’ve modeled our ByBlocks around the dimensions of a hollow cement block. Each is a 16 inch by 8 inch by 8 inch unit,” said Kujawa, and each brick is about 10 pounds lighter than a standard cement block.A cement block has rebar running through it, but ByBlocks uses a method called post tensioning, which requires a steel rod. As a sustainable option for building material, the repurposed plastic can be used for commercial, residential and infrastructure projects, Kujawa said.To that end, the business wants to partner with local governments, municipalities and corporations among other entities. It’s already selling both its Blocker System and completed ByBlocks but declined to specify customers or sales numbers thus far.”From the very beginning, we knew we wanted to be as carbon neutral as possible. So our block, our systems and our manufacturing process is an all electric, no emissions process today,” Kujawa said.The ultimate goal, she said, is to take the Blocker System to communities worldwide and enable them to repurpose plastic waste for use in local building projects. ByFusion hopes to be able to recycle 100 million tons of plastic by 2030.”Every community struggles with plastic waste,” Kujawa said. “Putting in a Blocker is going to help reduce landfill, reduce greenhouse gas emissions, reduce transportation needs, all of that other good stuff.”

LOS ANGELES — Imagine taking heaps and heaps of earth-polluting, unusable plastic waste and actually transforming it into something constructive?Plastic pollution is a proliferating and increasingly overwhelming problem. By 2040, estimates indicate that as much as 710 million tons of solid plastic waste will clog up the earth’s ecosystem, in oceans, rivers and on land.

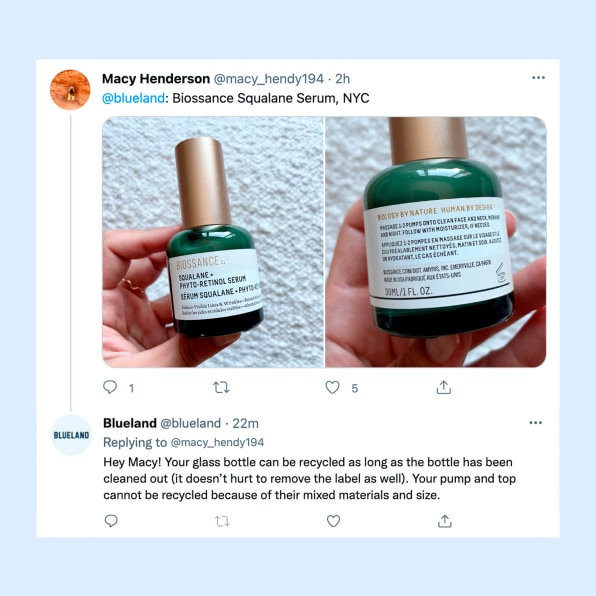

Blueland will help Twitter users recycle beauty products

Eco-friendly cleaning company Blueland is launching a Twitter service to help users recycle any beauty product—even from its competitors.

[Source Photos: Blueland]

By

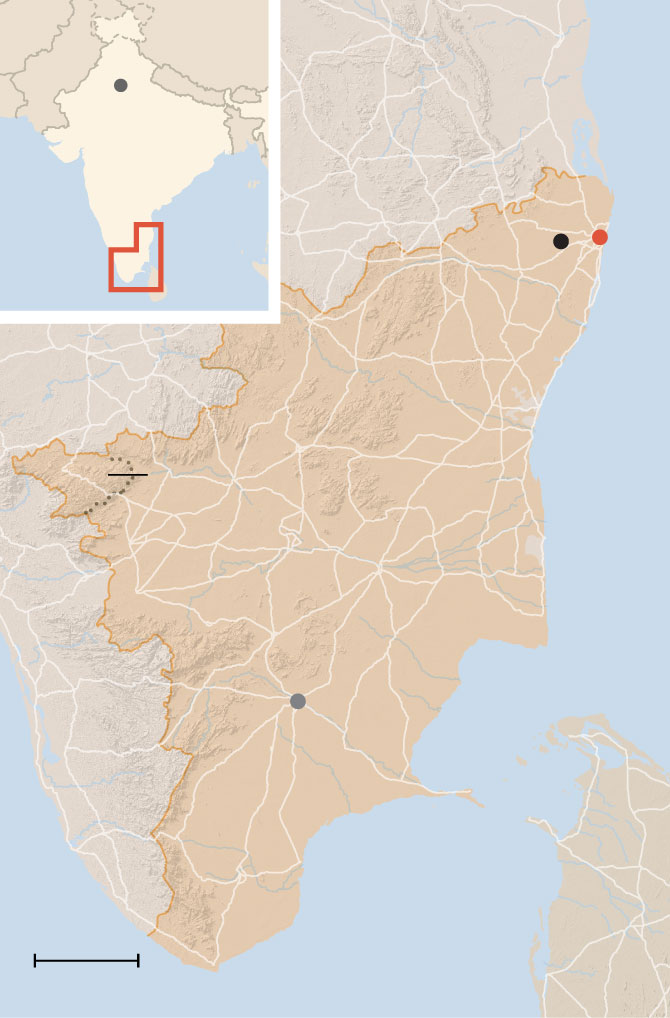

As India bans disposable plastic, Tamil Nadu offers lessons

Tamil Nadu’s ban on single-use plastic has gotten results, thanks to relentless policing. Now, India says it will tackle the problem nationwide.CHENNAI, India — Amul Vasudevan, a vegetable hawker in the southern Indian state of Tamil Nadu, thought she was going to go out of business.The state had forbidden retailers to use disposable plastic bags, which were critical for her livelihood because they were so cheap. She could not afford to switch to selling her wares in reusable cloth bags.Tamil Nadu was not the first state in India to try to curtail plastic pollution, but unlike others it was relentless in enforcing its law. Ms. Vasudevan was fined repeatedly for using throwaway bags.Now, three years after the ban took effect, Ms. Vasudevan’s use of plastic bags has decreased by more than two-thirds; most of her customers bring cloth bags. Many streets in this state of more than 80 million people are largely free of plastic waste.A shopper at a market in Chennai. As people have gotten used to providing their own shopping bags, plastic use has gone down.Anindito Mukherjee for The New York TimesYet Tamil Nadu’s ban is far from an absolute success. Many people still defy it, finding the alternatives to plastic either too expensive or too inconvenient. The state’s experience offers lessons for the rest of India, where an ambitious countrywide ban on making, importing, selling and using some single-use plastic took effect this month.

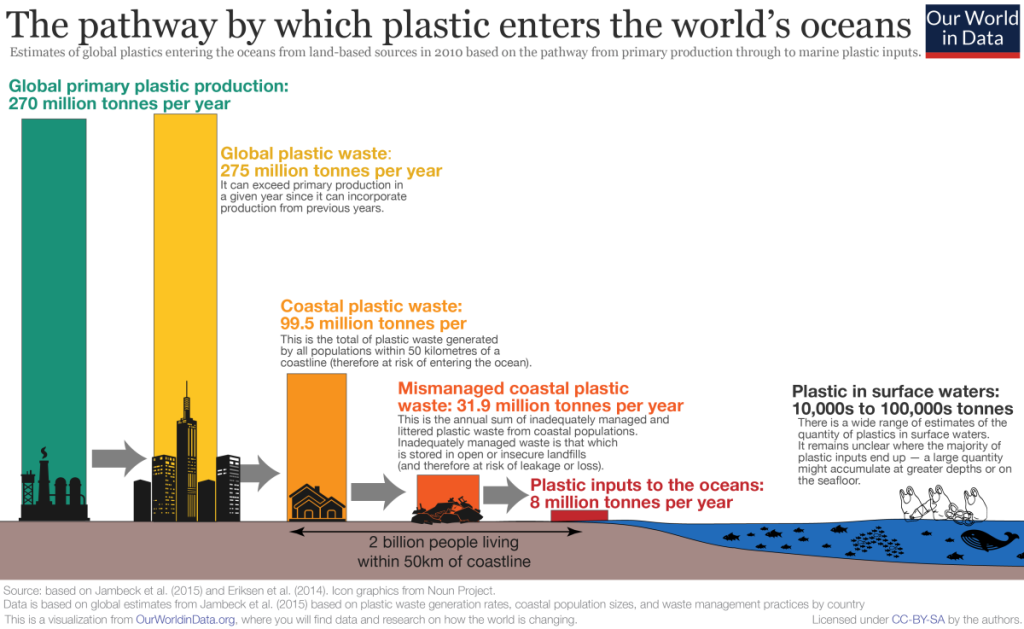

'It's in the water you drink', how ocean plastic pollutes the Earth

Humanity’s impact on the environment has never been more prominent, with a recent government report finding increasingly more severe weather events and less biodiversity.

But one environmental issue, recently named by the UN as one of the world’s biggest problems along with climate change, has flown under the radar.

Tens of millions of tonnes of plastic enter the ocean every year, either washing onto coastlines or accumulating into giant ocean garbage patches, where they can spend decades breaking down into toxic microplastics that are next to impossible to remove.