Humanity’s impact on the environment has never been more prominent, with a recent government report finding increasingly more severe weather events and less biodiversity.

But one environmental issue, recently named by the UN as one of the world’s biggest problems along with climate change, has flown under the radar.

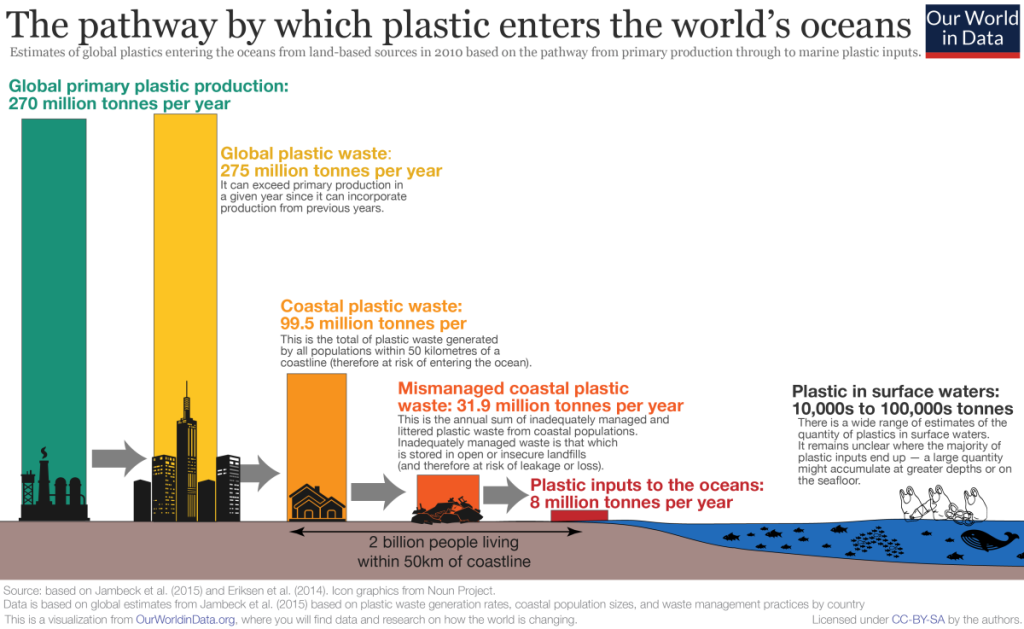

Tens of millions of tonnes of plastic enter the ocean every year, either washing onto coastlines or accumulating into giant ocean garbage patches, where they can spend decades breaking down into toxic microplastics that are next to impossible to remove.

And with global plastic production doubling every decade or so, this problem is only expected to get worse.

But experts say it’s not all doom and gloom. Mounting global efforts to reduce plastic waste reaching oceans, coupled with cutting-edge removal technologies, could reduce the impacts of ocean plastics on marine wildlife and the global ecosystem.

A good news, bad news story

In 1865, a US billiard ball manufacturer posted a newspaper ad offering $10,000 (about $250,000 today) to anyone who could replace solid ivory billiard balls with a suitable material that could be mass produced without the wholesale slaughter of elephants.

Although the celluloid billiard ball failed to win the $10,000 prize, it did start a global plastics revolution that has since taken over the world.

Associate professor of marine science at Sunshine Coast University, Dr Kathy Townsend, said plastic is a “good news, bad news story”.

“We’ve got this amazing material that’s really light, it’s inexpensive, and we can adapt it to all sorts of different shapes and sizes,” Dr Townsend told The New Daily.

“And it’s really been sort of like our modern miracle, including for things like medical use.

“But the problem is that we haven’t been very smart about how we’ve utilised the plastic that we’ve been creating.”

In 2016, the world produced more than 380 million tonnes of plastic.

That same year, as much as 23 million tonnes of plastic—or 11 per cent of the world’s plastic waste that year—entered the ocean, according to Science.

And with plastic production having more than doubled since 2000, that figure is expected to balloon to 53 billion tonnes by 2030.

Today, the world’s oceans contain as much as two hundred million tonnes of plastic, or about 10 per cent of the biomass of all fish.

By 2050, it is estimated plastics in the ocean will outweigh fish.

Rubbish islands and plastic snow

Most of the plastic that ends up in the ocean comes from mismanaged waste created on land, which is then carried out to sea on rivers.

It’s then swept on ocean currents into ‘gyres’, or giant vortexes that concentrate floating debris into giant patches, some as big as Queensland.

“There’s basically rubbish patches in every ocean of the world,” Dr Townsend said.

“And this is obviously a problem because animals hang out in those sorts of collections as well.”

Before plastic, ocean gyres would collect biological material, making them fruitful feeding grounds for marine wildlife, such as fish, turtles, whales and seabirds, Dr Townsend said.

Marine animals can get entangled in ocean plastics, causing lacerations, amputations, septicaemia, or even drowning. Or they can ingest the plastic.

“We estimate about a third of the sea turtles around the Australian coastline have consumed marine debris,” Dr Townsend said.

“But some places in the world like South America, for example, every single turtle that they’ve opened up, they found plastic in their gut.”

Ocean plastics will also break down in the wind, waves, and sun into microplastics that can be toxic to animals, including humans.

“And it’s everywhere,” Dr Townsend said.

“In your water bottle, it’s in the water that you drink.

“It’s been found absolutely everywhere across the planet. From snow on the highest mountains in the world, to the very deepest trenches in the ocean.”

The global cleanup

Because cleaning up microplastics is so difficult, the greatest chance we have of reducing plastic pollution in the ocean is by preventing it from reaching the ocean in the first place.

Last month, Australia and 20 other countries signed a global commitment to reduce ocean plastic pollution at the UN Ocean Conference.

Australia now joins more than 500 countries in agreeing to set ambitious goals to minimise waste mismanagement and maximise circular economy solutions.

Circular economy solutions reduce waste and greenhouse emissions by substituting resources that need to be cultivated or mined with waste.

“It’s not a straightforward solution,” Dr Townsend said.

“And that is why [ocean plastic pollution] has been labelled as a wicked problem, and why the UN has earmarked it as being one of the one of the world’s big global problems along with, of course, climate change.

“Am I optimistic we can fix this? One hundred per cent I am, because we have the technology.”

This week Dutch not-for-profit The Ocean Cleanup removed its 100th tonne of garbage from the great Pacific garbage patch by dragging giant nets behind container ships, though not without controversy.

Other, less invasive cleanup methods have achieved historic success.

But there’s a long way to go—on average Australia alone releases 100 tonnes of plastic into the ocean every seven hours.

Much of the plastic recovered from the ocean cannot be recycled through traditional means, but has been used to make highly durable construction materials that can replace emissions-heavy concrete.

But Dr Townsend said individuals can play a role too.

“People in their day-to-day lives, even though they don’t necessarily feel it, can actually make a difference,” she said.

“Making sure you take a reusable bottle with you, using a reusable coffee cup.

“Twenty thousand people doing it imperfectly is much better than one person doing it perfectly. Because it all adds up.”