Cigarette butt recycling scheme aims to stub out waste in CataloniaMove could provide income for homeless and clean up Barcelona’s streets and beaches, says government In a move that could provide some income for homeless people and clean up the streets, the Catalan government is looking at paying €4 to anyone who hands in a pack’s-worth of cigarette ends at a recycling point.The cost of the proposal would be covered by a 20-cent levy on each cigarette, its proponents say, which would nearly double the price of a pack of Marlboro Red from about €5 (£4.25), compared with about £13 in the UK.A similar levy on plastic bottles and aluminium cans introduced in New York City in 1982 has provided the homeless with a small but steady income.“We want to put a stop to the present situation where around 70% of cigarette butts end up either on the ground or in the sea,” Isaac Peraire, the head of the Catalan waste agency, told El Periódico earlier this week.According to the EU, cigarette butts are the second-most common single-use plastic found on European beaches – and the environmental organisation Ocean Conservancy says that of all the rubbish thrown into the sea, butts are the most numerous.In an effort to limit marine pollution, smoking will be banned on all of Barcelona’s city beaches from July. Spain’s Socialist-led coalition government is also planning to overhaul the country’s smoking laws to make it illegal to light up on the outside terraces of bars and restaurants, on beaches, and at open-air sports venues.According to figures from 2019, 19.7% of Spaniards smoke on a daily basis, slightly above the EU average of 18.4%. The three EU countries with the highest rates of smoking are Bulgaria (28.7%), Greece (23.6%) and Latvia (22.1%).The details of the levy plan have yet to be confirmed but one proposal is that the butts could be returned to the tobacconist or kiosk where the cigarettes were bought.“The idea isn’t to generate income but to reduce the environmental impact of these products,” Peraire said. “It’s hoped that one day this measure will cease to be necessary because the problem will have disappeared.”Meanwhile, the Spanish government is proposing that cigarette manufacturers should pay the cost of sweeping up butts and should educate the public not to discard them because they contain an environmentally damaging cellulose acetate.Andrés Zamorano, the president of the National Committee for the Prevention of Tobacco Use, said he was in favour of the measure because “tobacco comes at a high cost, not just from an environmental point of view, but because it pollutes public spaces”.Zamorano conceded, however, that tobacco companies were likely to add the clean-up cost to the price of their products.Ismael Aznar Cano, director general for quality and assessment at Spain’s environment ministry, said the proposal came within the context of a law on waste due to take effect at the start of 2023.The law will prohibit the sale of plastic cotton buds, cutlery, plates, expanded polystyrene cups and plastic straws, although cigarette butts are not yet covered by the law.Spain is not the only country trying to address the issue. In 2016, Naman Gupta and Vishal Kanet, two Young Indian entrepreneurs, launched a project to recycle some of the estimated 100 billion butts that are dumped every year in the country.They devised a scheme to collect cigarette ends and a process that separates any remaining tobacco, which is recycled into compost, while the filters are treated and made into a substance used for stuffing soft toys and cushions.Another Indian scheme launched in Kolkata last year is ButtRush, which organises the collection of butts for recycling.On the island of Guernsey, authorities have introduced so-called ballot bins where the public can vote on local issues or the result of a football match by depositing their fag ends in a bin showing their preferred option.The bins are at the bus station and outside a chemist’s shop, where cigarette butt pollution is said to have fallen by 46%.In the United States, the recycling firm TerraCycle offers businesses a free collection service and will recycle not only cigarette ends but also the packaging and the foil lining. And in the French city of Bordeaux, a public-private partnership collects and recycles up to 200,000 butts a year and has so far collected more than 1.5 million. Similar action has been taken in nearby Toulouse.One study suggests that there are 4.5 trillion butts littering the environment. The plastic in the filters takes up to 10 years to biodegrade, releasing toxic arsenic and lead as they do so.According to the World Health Organization, tobacco waste contains up to 7,000 toxic chemicals.It is not uncommon to find cigarette ends in the bodies of dead fish and sea birds and they can be lethal to freshwater and marine species.There are no precise figures for the cost of cleaning up cigarette ends in Spain. However, a Catalan study estimates the cost at €12-21 each inhabitant a year, with the cost highest in coastal areas.TopicsBarcelonaCataloniaSpainEuropeTobacco industrySmokingPollutionnewsReuse this content

Category Archives: Land

FDA sparks anger with decision on ‘phthalates’ — a chemical in fast-food packaging

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) said Thursday that it will not impose a total ban on a set of dangerous chemicals commonly found in fast-food packaging, angering scientists and environmental groups who have long pressed for their removal.

The decision came in response to three separate petitions requesting that the FDA limit the use of compounds called phthalates, which are known to disrupt hormone function and have been linked to birth defects, infertility, learning disabilities and neurological disorders.

Despite proven negative health impacts, the compounds are still common ingredients in food packaging. Scientists have found that marginalized groups suffer disproportionately from the chemicals, partly because they consume more fast food.

The FDA on Thursday did institute a ban on the use of 23 phthalates for food contact applications, but it noted that those particular compounds had already “been abandoned” by manufacturers anyway. In taking its action, the FDA agreed to a July 2018 petition submitted by an industry group known as the Flexible Vinyl Alliance.

The FDA will still allow the use of nine other similar compounds in food contact applications. And it denied a separate petition on Thursday from several environmental groups that had asked it to ban the 23 phthalates and an additional five from having food contact.

It said the organizations that had brought the petition, including the Natural Resources Defense Council, Earthjustice and the Environmental Defense Fund, “did not demonstrate that the proposed class of phthalates is no longer safe for the approved food additive uses.”

The FDA also denied another related petition — from some of the same environmental groups — that requested a ban on food contact use for certain phthalates and the revocation of previously sanctioned authorizations for others.

The FDA said it rejected this petition because it failed to “demonstrate through scientific data or information” that such a ban on phthalates was warranted.

Several groups in a research consortium called Project TENDR — Targeting Environmental Neuro-Developmental Risks — condemned the FDA’s decision.

“These chemicals are approved for their use, they have the ability to leach out of these products into the food, they’re ending up in our food in our bodies and are leading to serious and irreversible health effects,” said Ami Zota, an associate professor at the George Washington University’s Milken Institute School of Public Health who is a member of Project TENDR.

“That can affect the basics of human condition — like our ability to learn, our ability to have safe and healthy families,” she added. “And marginalized communities are disproportionately being burdened.”

A statement from the consortium faulted the agency for leaving “numerous authorizations in place that perpetuate phthalate contamination of the food supply.”

Earthjustice, one of the organizations behind the rejected petitions, pointed out that although Congress deemed many phthalates too dangerous for use in children’s toys more than a decade ago, the FDA is enabling the continued “contamination of food and drinks.”

“FDA’s decision recklessly green-lights ongoing contamination of our food with phthalates,” Earthjustice attorney Katherine O’Brien said in a statement.

She accused the agency of “putting another generation of children at risk of life-altering harm” while “exacerbating health inequities experienced by Black and Latina women.”

“FDA’s announcement that it will now start reviewing new data on phthalate safety — six years after advocates sounded the alarm — is outrageous and seeks to sidestep FDA’s legal duty to address the current science in proceedings on the existing petitions,” O’Brien added.

In January, the House Oversight and Reform Committee sent a letter to the FDA demanding that the agency take immediate action to address this class of compounds, as The Hill previously reported.

The previous month, health and environmental advocates sued the FDA over its failure to rule on the 2016 petition that was rejected on Thursday. The FDA was required by law to respond to the principal petition within 180 days of filing, according to the suit.

Asked why the agency would have approved the industry petition, but rejected the two broader petitions from the environmental organizations, Zota said that she could not speak to the FDA’s rationale or motivation.

She suggested, however, that the point of the industry petition may have been to “continue use of those phthalates that are most commonly used in plasticizers” — compounds that serve to soften plastics.

“Here is a way we can prevent impaired learning and reproduction in all Americans, but especially the most vulnerable,” she said. “Here’s a pathway to prevention. We do not need more science. The science is clear.”

In response, Flexible Vinyl Alliance’s executive director, Kevin Ott, said that members of the group requested that the FDA ban 25 phthalates as they are “simply no longer employed in food contact or packaging applications.”

To succeed with the petition, Ott explained, the group also worked across the industry to survey real-life use of phthalates in food packaging — determining that their removal would help assure consumers that unnecessary chemicals are no longer used in contact with food.

Alongside these decisions, the agency also issued a request for information on Thursday, with the goal of “seeking available use and safety information on the remaining phthalates authorized for use.”

“The FDA is generally aware of updated toxicological and use information on phthalates that is publicly available,” the agency said in a statement. “Nevertheless, stakeholders may have access to information that is not always made public.”

New Zealand’s Ardern to meet with senators during trip to boost trade, tourism

Baby formula bill faces rocky terrain in Senate

Zota disputed the notion that the scientific information is insufficient, urging “the FDA to make evidence-based decisions to protect the health of Americans.”

“Given the ubiquity of the problem and its magnitude on health, we need upstream policy decisions, policy action, and this is in FDA’s regulatory authority,” she added.

— Updated at 6:35 p.m.

Environmental toxics are worsening obesity pandemic, say scientists

Environmental toxins are worsening obesity pandemic, say scientistsExclusive: Pollutants can upset body’s metabolic thermostat with some even causing obesity to be passed on to children Chemical pollution in the environment is supersizing the global obesity epidemic, according to a major scientific review.The idea that the toxins called “obesogens” can affect how the body controls weight is not yet part of mainstream medicine. But the dozens of scientists behind the review argue that the evidence is now so strong that it should be. “This is critical because the current clinical management of obese patients is woefully inadequate,” they said.The most disturbing aspect of the evidence is that some chemical impacts that increase weight can be passed down through generations by changing how genes work. Pollutants cited by the researchers as increasing obesity include bisphenol A (BPA), which is widely added to plastics, as well as some pesticides, flame retardants and air pollution.Global obesity has tripled since 1975, with more people now obese or overweight than underweight, and is increasing in every country studied. Almost 2 billion adults are now too heavy and 40 million children under five are obese or overweight.“The focus of the clinical people is on calories – if you eat more calories, you’re going to be more fat,” says Dr Jerrold Heindel, lead author of one of the three review papers, and formerly at the US National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. “So they wait untill you get obese, then they’ll look at giving you diets, drugs, or surgery.“If that really worked, we should see a decline in the rates of obesity,” he said. “But we don’t – obesity continues to rise, especially in children. The real question is, why do people eat more? The obesogenic paradigm focuses on that and provides data that indicate that these chemicals are what can do that.”Furthermore, the scientists say, the approach offers the potential to prevent obesity by avoiding exposure to pollutants, especially in pregnant women and babies: “Prevention saves lives, while costing far less than any [treatment].”Strong evidenceThe evidence for obesogens is set out by more than 40 scientists in three review papers, published in the peer-reviewed journal Biochemical Pharmacology and citing 1,400 studies. They say these chemicals are everywhere: in water and dust, food packaging, personal hygiene products and household cleaners, furniture and electronics.The review identifies about 50 chemicals as having good evidence of obesogenic effects, from experiments on human cells and animals, and epidemiological studies of people. These include BPA and phthalates, also a plastic additive. A 2020 analysis of 15 studies found a significant link between BPA levels and obesity in adults in 12 of them.Other obesogens are pesticides, including DDT and tributyltin, former flame retardants and their newer replacements, dioxins and PCBs, and air pollution. Several recent studies link exposure to dirty air early in life to obesity.The review also names PFAS compounds – so-called “forever chemicals” due to their longevity in the environment – as obesogens. These are found in food packaging, cookware, and furniture, including some child car seats. A two-year, randomised clinical trial published in 2018 found people with the highest PFAS levels regained more weight after dieting, especially women.Some antidepressants are also well known to cause weight gain. “That is a proof of principle that chemicals made for one thing can have side effects that interfere with your metabolism,” said Heindel. Other chemicals with some evidence of being obesogens included some artificial sweeteners and triclosan, an antibacterial agent banned from some uses in the US in 2017.How it worksObesogens work by upsetting the body’s “metabolic thermostat”, the researchers said, making gaining weight easier and losing weight harder. The body’s balance of energy intake and expenditure through activity relies on the interplay of various hormones from fat tissue, the gut, pancreas, liver, and brain.The pollutants can directly affect the number and size of fat cells, alter the signals that make people feel full, change thyroid function and the dopamine reward system, the scientists said. They can also affect the microbiome in the gut and cause weight gain by making the uptake of calories from the intestines more efficient.“It turns out chemicals dumped in the environment have these side effects, because they make the cells do things that they wouldn’t otherwise have done, and one of those things is laying down fat,” said Prof Robert Lustig at the University of California, San Francisco, and lead author of another of the reviews.The early years of child development are the most vulnerable to obesogens, the researchers wrote: “Studies showed that in utero and early-life exposures were the most sensitive times, because this irreversibly altered programming of various parts of the metabolic system, increasing susceptibility for weight gain.”“We’ve got four or five chemicals that also will cause transgenerational epigenetic obesity,” said Heindel, referring to changes in the expression of genes that can be inherited. A 2021 study found that women’s level of obesity significantly correlated with their grandmothers’ level of exposure to DDT, even though their granddaughters were never directly exposed to the now banned-pesticide.“People need to know that [obesogenic effects] are going on,” Lustig said. “Because it affects not just them, but their unborn children. This problem’s going to affect generation after generation until we get a hold of it.”Cause and effectDirectly proving a causal link between a hazard and a human health impact is difficult for the simple reason that it is not ethical to perform harmful experiments on people. But strong epidemiological evidence can stack up to a level equivalent to proof, such as with tobacco smoking and lung cancer.Lustig said that point had been reached for obesogens, 16 years after the term was first coined. “We’ll never have randomised control trials – they would be illegal and unethical. But we now have the proof for obesogens and obesity.”The obesogen paradigm has not been taken up by mainstream researchers so far. But Prof Barbara Corkey, at Boston University School of Medicine and past president of the Obesity Society, said: “The initial worldview was that obesity is caused by eating too much and exercising too little. And this is nonsense.“It’s not the explanation because all of the creatures on Earth, including humans, eat when they’re hungry and stop when they are full. Every cell in the body knows if you have enough food,” she said. “Something has disrupted that normal sensing apparatus and it is not volition.“People who are overweight and obese go to tremendous extremes to lose weight and the diet industry has fared extremely well,” Corky said. “We’ve learned that doesn’t work. When the medical profession doesn’t understand something, we always blame patients and unfortunately, people are still being held responsible for [obesity].”Lustig said: “Gluttony and sloth are just the outward manifestations of these biochemical perturbations that are going on beneath the surface.”Super-sizedHow much of the obesity pandemic may be caused by obesogens is not known, though Heindel said they will have an “important role”.Lustig said: “If I had to guess, based on all the work and reading I’ve done, I would say obesogens will account for about 15% to 20% of the obesity epidemic. But that’s a lot.” The rest he attributes to processed food diets, which themselves contain some obesogens.“Fructose is a primary driver of a lot of this,” he said. “It partitions energy to fat in the liver and is a prime obesogen. Fructose would cause obesity even if it didn’t have calories.” A small 2021 trial found that an ultra-processed diet caused more weight gain than an unprocessed diet, despite containing the same calories in the meals offered to participants.Cutting exposure to obesogens is difficult, given that there are now 350,000 synthetic chemicals, many of which are pervasive in the environment. But those known to be harmful can be removed from sale, as is happening in Europe.Heindel said prospective mothers in particular could adjust what they eat and monitor what their children play with in their early years: “Studies have shown modifying diets can within a week or so cause a significant drop in several obesogens.”Lustig said: “This cause is very pervasive and pernicious, and it’s also lucrative to a lot of [chemical] companies. But we must address it rationally.” To do that, the “knowledge gap” among doctors, regulators and policymakers must be addressed, the scientists said.“It’s time now that [obesity researchers and clinicians] should start paying attention and, if they don’t think the data is strong enough, tell us what more to do,” said Heindel, who is organising a conference to tackle this issue.Sign up to First Edition, our free daily newsletter – every weekday morning at 7am BSTCorkey is yet to be fully convinced by the obesogen paradigm, but said the concept of an environmental toxin is probably the right direction to go in. “Is there proof? No, there is not,” she said. “It’s a very difficult problem, because the number of chemicals in our environment has just astronomically increased.“But there’s no alternative hypothesis that to me makes any sense and I would certainly challenge anyone who has a better, testable idea to come forth with it,” she said. “Because this is a serious problem that is impacting our societies enormously, especially children. The problems are getting worse, not better – we’re going in the wrong direction as it stands.”TopicsPollutionObesityHealthPlasticsPesticidesnewsReuse this content

Sunken trash made into treasure

Four months ago The Tyee looked in on a volunteer team of divers who pull junk from the bottom of lakes in B.C. and had begun handing their finds to artists. Announcements, Events & more from Tyee and select partners Ten Award Nominations for Tyee Journalists Finalists are named for Canada’s prestigious National Magazine Awards …

More than 3,000 potentially harmful chemicals found in food packaging

More than 3,000 potentially harmful chemicals found in food packagingInternational experts who analyzed more than 1,200 scientific studies warn chemicals are being consumed with unknown long-term impacts Scientists have identified more than 3,000 potentially harmful chemicals that can be found in food packaging and other food-related materials, two-thirds of which were not previously known to be in contact with food.An international group of scientists analyzed more than 1,200 scientific studies where chemicals had been measured in food packaging, processing equipment, tableware and reusable food containers.A report released on Thursday by the Food Packaging Forum, a Switzerland-based non-profit, noted little is known about many of the 3,240 chemicals examined in these studies or their effects on people.Manufacturers are either intentionally or unintentionally adding these chemicals to packaging and other equipment, said Pete Myers, a report co-author and founder and chief scientist of Environmental Health Sciences, a non-profit advocacy group. Either way, many of those chemicals are ending up in the human body, he said.“If we don’t know what it is, we don’t know its toxicity,” Myers said. “The mix of chemicals is just too complicated to allow us to regulate them safely.”The new analysis, published in the journal Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, comes amid growing concerns about exposure to potentially toxic chemicals in food and water.The Food Packaging Forum has created a searchable database with the chemicals found in the packaging and equipment, known as food contact materials. While many of the chemicals on the list are known hazards such as phthalates and PFAS, others have not been adequately studied, the group said, and their health effects are unclear.Researchers were shocked to find chemicals in food contact materials that consumers could have no knowledge of. Just one-third of the chemicals studied appeared in a previously compiled database of more than 12,000 chemicals associated with the manufacturing of food contact materials.Previous studies have found potentially dangerous PFAS “forever chemicals” in food packaging. Those chemicals have been linked to a list of health problems.Nearly two-thirds of the studies analyzed in the new report looked at chemicals in plastic. Packaging manufacturers often add chemicals without knowing the long-term ramifications, said Jessica Heiges, a UC Berkeley doctoral candidate who studies disposable food items such as plasticware and packaging and was not involved in the report.The chemicals “are terrifying because we don’t know what their impacts are”, Heiges said. “What’s most alarming is this cocktail of chemicals, how they’re interacting with each other. Some of them are persisting in the environment and in our bodies as we’re consuming them.”It’s likely many of those unknown chemicals are harmful, said Alastair Iles, an associate professor in UC Berkeley’s environmental science, policy and management department, also not involved with the study.“The report only underlines our gross ignorance when it comes to the chemicals that people are being exposed to every day,” he said. “If we didn’t know that there were so many chemicals in packages, what does that say about our knowledge about chemical risks?”TopicsFood safetyOur unequal earthPFASFood & drink industrynewsReuse this content

The plastic alternative the world needs

By Alex Zhang

So, we all agree plastics are bad, right?

Plastics may be a villain in earth’s very own TV series, but without it, many inventions would not be possible today. Plastic has given us computers, solar panels, and even that iPhone you cannot live without.

However, traditional plastics are typically made from fossil fuels, and therefore contribute to the ongoing climate crisis. According to a UN Environment Program (UNEP) report, fossil fuel-based plastics alone account for an estimated 15 percent of the world’s carbon budget, equivalent to approximately 1.7 gigatons of CO2. Emissions from producing these harmful plastics are equivalent to 116 coal-fired power plants last year.

Fossil fuel-based plastic is also kind of immortal. These materials do not break down efficiently in the environment and end up sitting in landfills for hundreds and thousands of years; or they are burned with other trash, releasing toxic gas into the environment.

To make things more complicated, ‘greenwashing’ has become a troubling issue in recent years as companies attempt to use corn-based materials that they market as ‘compostable’. These corn-plastic products do not degrade as promised if they end up in forests or oceans.

Fossil fuel-based plastic is also kind of immortal. These materials do not break down efficiently in the environment and end up sitting in landfills for hundreds and thousands of years

However, there are startups trying to solve all of these problems by using innovative materials to make truly biodegradable products.

Close-up of text on plastic cup reading Made From Corn, referring to plant derived bioplastics, … [+] commonly used in servingware in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Getty Images

The Good News – Bioplastics

Unlike traditional plastic, bioplastics are typically made from renewable sources such as plants, starches, and sugars. One of the most advanced bioplastic materials is called PHA (Polyhydroxyalkanoates). It’s an excellent alternative to traditional fossil fuel-based plastic because it offers a completely compostable solution, biodegradable in all types of natural environments. Products made of PHA will completely decompose without any special treatment, which is crucial for preventing single-use plastic pollution.

For example, single-use straws made of traditional plastics can take up to 200 years to degrade on land or in the ocean. However, single-use straws made of PHA will degrade in just 90 days when buried in soil and 180 days in the ocean.

One of the most advanced bioplastic materials is called PHA (Polyhydroxyalkanoates). It’s an excellent alternative to traditional fossil fuel-based plastic because it offers a completely compostable solution, biodegradable in all types of natural environments.

What About Our Oceans?

Preventing traditional plastics from entering the ocean is crucial to the health of our planet. For many decades, plastic has been improperly disposed of by society, which has caused plastics to build up in the ocean at an alarming rate. An Environmental Investigations Agency (EIA) study says that plastic will outweigh fish in the planet’s oceans by 2050. Since traditional plastics are made of petrochemicals and designed to be durable, their products are not naturally biodegradable and often contain harmful toxins. Unless these materials are removed by humans, plastic that ends up in the ocean will remain there indefinitely. Traditional plastic products have also been found to break down into microplastic. Marine animals sometimes eat microplastics, which in turn endangers human food safety by ending up on our plates.

PHA has been found to be one of the only bioplastics that will properly and efficiently break down in the ocean. Products made of PHA are denser than water, which means PHA is more likely to sink compared to other plastics. The soil at the bottom of the ocean helps with the biodegradation process and allows for the PHA to decompose faster than if it were to be free-floating. According to studies, the rate of degradation depends on the surface area of the product. Smaller products, such as straws, take just six months to disappear.

PHA has been found to be one of the only bioplastics that will properly and efficiently break down in the ocean.

Close-up of disclaimer included on corn-based plastic packaging (2022).

Alex Zhang

How is PHA Different from ‘Corn-Plastics’?

A more commonly recognized type of bioplastic is polylactic acid, or PLA, a material made from corn. Today, PLA (or corn-plastic) is made into single-use products such as straws, bottles, and other packaging materials. While PLA is technically considered ‘compostable’, products made of PLA need to be specially treated in industrial composting facilities in order to be properly biodegraded. This is because PLA needs to be heated to at least 140°F/60°C (a temperature that does not usually exist in nature) and fed special microbes to break the bioplastic back down into sugars.

Additionally, if PLA products are recycled, they must be separated as they will contaminate the recycling process. When tossed in the trash, PLA products can take 100 to 1000 years to completely degrade. Despite their marketing, this effectively makes PLA just as bad as traditional plastics.

Unlike PLA, PHA products do not need to be specially treated in order to break down. When PHA products are disposed, they will degrade in the natural environment.

Startups Pioneering Plastic Pollution Solutions

In recent years, a handful of startups have emerged to address the single-use plastic pollution problem. Companies like Full Cycle and Genecis focus on using food waste and agricultural byproducts to make PHA raw material. Refork developed a single-use fork by blending wood flour, PHA polymer, and minerals. Even more, OMAO leads in the development of naturally biodegradable tableware made from PHA. OMAO has replaced over 5,000 pounds of traditional plastics by offering PHA straws. The company is also working on other single-use tableware products in an effort to make sustainability even easier for everyone.

The plastic pollution problem looms, and it can often feel unaddressable because of its size and complexity. But it’s important to recognize that there are solutions out there for cleaning up our plastic use—and there are surely many more to come.

Alex Zhang (’22) is a Columbia Business School MBA candidate and the founder of OMAO. His background includes both founding an environmental tech startup and working as an investment professional.

Why labor leader Tefere Gebre has brought his organizing talents to Greenpeace

Tefere Gebre’s biography has touched on the major crises affecting the planet: the massive rise in refugees, skyrocketing economic inequality and climate change. The first of those cataclysms was thrust upon him when he was just a teenager. He fled the civil war in Ethiopia, enduring a perilous 2½ week journey through the desert. “Sometimes you’d find yourself where you were a week ago,” he told Orange Coast magazine in 2014. He spent five months in a refugee camp in Sudan before arriving in Los Angeles, where he attended high school.

As an adult, Gebre became active in the labor movement, organizing trash sorters in Anaheim and holding leadership positions at the Orange County Labor Federation and the AFL-CIO, where he served as executive vice president. In February, he took the position as chief program officer at Greenpeace USA, the 3 million-member direct action organization known for its high-profile banner drops, opposition to whale hunting and campaign against plastic waste.

Capital & Main spoke to Gebre two days before Greenpeace held its first-ever protest in solidarity with fossil fuel workers. Two boats with activists from Greenpeace USA and United Steel Workers Local 5 members formed a picket line from land into San Francisco Bay as an oil tanker headed to Chevron’s Richmond refinery in what Gebre described as “a genuine attempt to build a transformational relationship” with the striking workers. Nearly 500 refinery employees went on strike over safety and salary concerns in March. The two sides have yet to come to an agreement. The oil tanker crossed the picket line, according to sources at Greenpeace.

Note: This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Tefere Gebre, center, with activists from Greenpeace USA and USW workers sailing in solidarity with striking workers from Chevron’s Richmond refinery on April 29. Photo: Nick Otto / Greenpeace.

Capital & Main: You’ve been a labor leader for most of your career. Can you talk about why you decided to make this move?

Tefere Gebre: In 2017, I had my first child, who’s now 5 years old, and she brought a lot of things into perspective for me. I’m worried sick that if things continue the way they are, I’m never going to see her graduate from high school or college. I just felt like she was going to hold me accountable.

I also know that the workers’ movement is going to be crucial in actually solving this problem. We have been fed wrong choices and wrong narratives for years. Either we have to take good paychecks, family-sustaining paychecks, or choose to breathe clean air. I don’t think that’s a choice.

Also, for ages, people like myself have imagined the environmental movement to be a movement for upper-middle-class white people. But I grew up in Los Angeles. I know the asthma corridor in Los Angeles — the 110 freeway which leads to the ports. Those are little Black and brown kids, who have nothing to do with polluting the environment. They are born with asthma. I want the environmental movement to actually be their movement, driven by them and led by them.

Is your appointment to this executive position at Greenpeace a sign that Greenpeace is moving in a new direction?

Absolutely. Eight years ago, 13% of Greenpeace’s staff was BIPOC [Black, Indigenous and people of color]. Today, it’s 52%. It is by design. In a real way, they want to do equity and inclusiveness. I’m the first immigrant and Black man they ever had in a leadership position.

“We know, at the end of the day, those large corporations are going to try to profit from the new, cleaner energy sources. But they have no plan to transition fossil fuel workers into that sector.”

How are you going to build the partnership between labor and the environmental movement in your current role?

I’m going to talk directly to fossil fuel workers, those who work at the refineries, and those who work to actually take the oil out of the ground. I want them to actually imagine a better life for themselves, and explain that the environmental movement — at least Greenpeace — is not against them. We’re with them. We’re against the people who take advantage of them at work and would take advantage of their community, and pollute our environment.

The emerging, new, clean energy jobs are also going to be good jobs, and they are not going to be good jobs just because we wish them to be good. We have to work hard on [making them good].

To the environmental movement, I will bring the perspective that we don’t just fight for solar panels and wind. We also have to fight for those jobs becoming family-sustaining jobs and union jobs.

When I think of Greenpeace, I think of bold acts of civil disobedience, confronting oil tankers at sea and so forth. Labor unions are often interested in pocketbook issues that affect people’s daily lives. How do you bring these two movements together?

Some in the building trades specifically have had clashes with the environmental movement. For a long time, when I was in the labor movement, I used to say, “They are letting you fight their dirty fight.” We know, at the end of the day, those large corporations are going to try to profit from the new, cleaner energy sources. But they have no plan to transition fossil fuel workers into that sector. They just make them do their dirty fight [against environmental regulation].

They don’t have any conversation with their unions about how they’re going to transition into [clean technologies]. They just scare them about their current job, and say, “The environmentalists just don’t care about you,” and all that stuff. So it’s on us to prove them wrong, and be laser-focused on who the enemy is here. Not the workers. It’s the corporations.

“It’s a mystery to me how people are not really, really outraged that Exxon gets billions of dollars from the government for free.”

There’s obviously an incredible urgency to the climate crisis. And this work of building partnerships across constituencies takes time and patience, trial and error. Is there time to do the work that needs to be done in that area?

We have to do this as quickly as possible. We believe that we are in a climate emergency right now. The thing is, how do we get our government to respond to that emergency? Our government was willing to print all kinds of money because of a pandemic … Now, just imagine, if our government actually puts a trillion dollars onsite for incumbent fossil fuel workers and says, “Go innovate your future job, and help us build clean energy.” What would happen?

But the thing is, including in California, most politicians are in the pocket of the fossil fuel economy. People think the fossil fuel industry is just polluting our air. They’re polluting our democracy. They’re polluting our politics … In California, we practically have a Chevron caucus in the Legislature.

Clearly, they have a lot of power and resources. Do you think that explains it?

The lack of investment [in clean energy alternatives] is a problem. I have met with people who believe they have the technology to make dissolvable plastics, for example. You can have your Safeway plastic bag and put it in the water. It will stay there for a million years. They have plant-based plastics that can dissolve.

I ask them, “How can we get this to market?” Their answer to me was that they can’t compete with the fossil fuel industry, about 45% of which is plastics. That’s what they use fossil fuels for.

You can’t do both. You can’t be feeding something you’re trying to kill. It’s a mystery to me how people are not really, really outraged that Exxon gets billions of dollars from the government for free.

Here’s the core of it. There ain’t going to be any jobs on a dead planet. And I think the more workers understand that the more they are willing actually to look at the longer view of this.

That’s a pretty stark phrase. And getting people to believe that the government can and will do enough to avoid the worst impacts seems to be one of the key challenges.

In a democracy, people are the government. They can make the government do it. That’s why we need to activate and actually demand. When voters demand things, they get what they want.

Copyright 2022 Capital & Main

We need sustainable food packaging now. Here’s why

Every day, hundreds of millions of single-use containers, cans, trays, and cutlery are thrown away around the world. While packaging is an essential component of the food sector and the only solution we have to facilitate food transportation, food packaging waste is also one of the most harmful aspects of this industry. We outline the advantages and disadvantages of the most popular materials used to wrap groceries and takeaway foods and explore innovative sustainable food packaging that could revolutionise the market and protect the environment.

—

Why Do We Use So Much Food Packaging?

In ancient history, humans used to consume food from where it was found. There were no grocery shops, takeaway and delivery services, and almost no imports and exports of food on a global scale. But things changed rapidly in the 20th century. Suddenly, countries began shipping produce from one end of the world to the other; supermarkets in the US started selling Southeast Asian tropical fruits; China depended on Brazil for its soybean supplies; and European countries were importing coffee from Africa. The emergence and subsequent surge in international shipping of food staples led to a revolution in the packaging sector.

Since food needed to travel long distances to keep up with global demand, it became crucial to find ways to ensure food remained fresh and undamaged at the time of consumption. Packaging turned out to be the best way to extend food shelf-life as it retarded product deterioration, retained the beneficial effects, and maintained the nutritional values, characteristics, and appearance of foods for longer times.

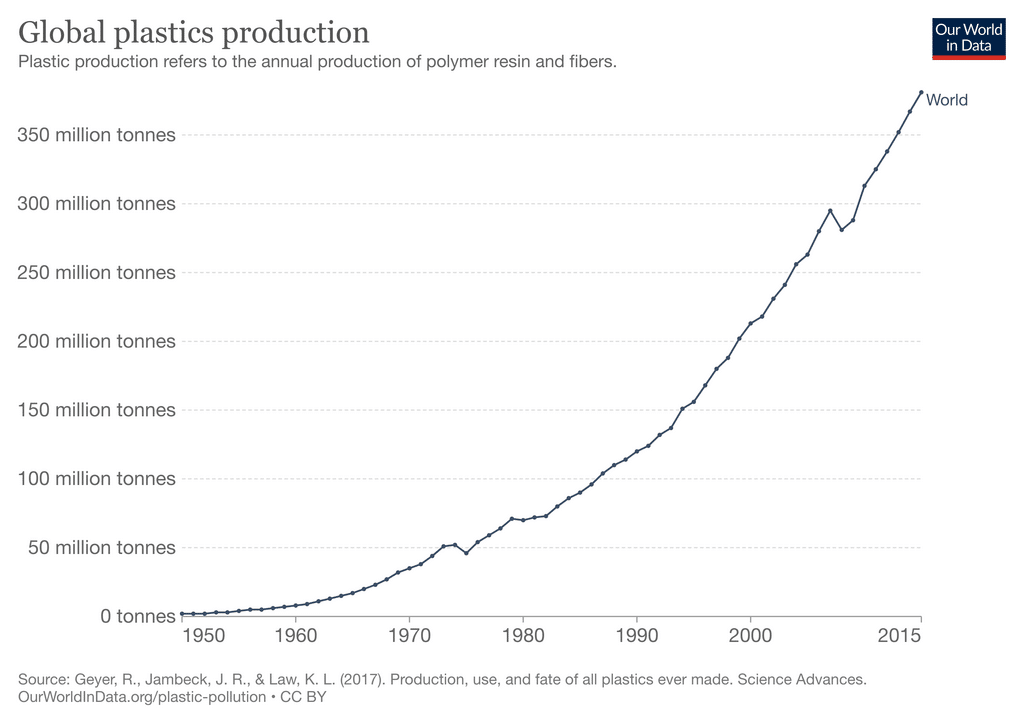

Materials that have been traditionally used in food packaging include glass, metals (aluminium, foils and laminates, tinplate, and tin-free steel), paper, and paperboards. Plastic, by far the most common material used in food packaging today, is also the newest option. Since the plastic boom in the early 1980s, new varieties of this material have been introduced in both rigid and flexible forms, slowly replacing traditional materials due to their versatility, easy manufacturing process, and cheap price. Of all plastics produced worldwide today, nearly 40% are used for food and drink packaging.

Figure 1: Worldwide Plastic Production, 1950-2015

But food retailers are not the only industry that contributed to the rapid acceleration in plastic and packaging production. Consumer habits changed drastically within the restaurant industry too. The first takeaway options were already available in the 1920s, but it was not until after World War II that consumers started appreciating the convenience of drive-throughs and other take-home options. In America, fast food chains such as In-N-Out Burger and McDonald’s were responsible for the industry’s boom and with the expansion of the transportation industry, delivery options also began expanding around the world. This inevitably led to a massive influx of food packaging solutions that allowed consumers to pick up pre-cooked dishes and consume them elsewhere.

Most of the containers that we have today are single-use, non-compostable, and difficult to degrade because of food contamination. Both the restaurant and retail industries are major contributors of food packaging waste. Finding a balance between food protection and environmental consciousness undoubtedly requires huge efforts. Given the increasing consumer (and manufacturer) awareness of the environmental and health impacts of non-degradable packaging, in recent years the packaging industry has been seriously looking at alternative, more environmentally friendly materials as well as ways to reduce packaging where it is not absolutely necessary. Restaurants, in particular, have seen sustainable packaging options widely expanded to include compostable and recyclable packaging. According to Globe News Wire, the biodegradable packaging market will reach a value of USD$126.85 billion by 2026.

Where Does All the Food Packaging Waste Come From?

Single-use packaging is taking a huge toll on our environment. Almost all food containers we see in grocery stores – typically made of glass, metal, plastic, or paperboard – cannot be reused for their original function, such in the case of aluminium cans and most plastic bags. However, food contamination is a big consideration. Though some types of packaging might be suitable to be reused, some experts have raised hygiene concerns in replacing single-use food service ware with reusable items, both within the food retail and the restaurant industries.

Another big hurdle that companies studying sustainable food packaging alternatives are trying to solve is over-packaging. Nowadays, food retailers tend to encase products in multiple layers. More often than not, food items such as fruit and vegetables are placed on a tray, wrapped in paper or plastic, and then placed into a paperboard box. On top of that, consumers might opt for a plastic bag to carry groceries home, adding to the already huge pile of waste generated from a single trip to the supermarket. Additionally, conventional materials are still extremely widespread worldwide despite a multitude of new sustainable alternatives entering the market every year. A 2021 survey found that over 80% of food packaging examined is not suitable for recycling.

Detail-oriented societies such as Japan – where quality, presentation, and customer satisfaction are particularly valued – are among the biggest culprits in terms of unnecessary packaging and waste generation. The United States alone produces an estimated 42 million metric tons of plastic waste each year – more than any other country in the world. Most of it occurs in grocery shops. A Greenpeace UK report found that every year, seven of the country’s top supermarkets are responsible for generating almost 60 billion pieces of plastic packaging – a staggering 2,000 pieces for each household. And in the European Union, the estimated packaging waste per capita in 2019 was 178.1 kilogrammes (392 pounds), with paper and cardboard making up the bulk of it, followed by plastic and glass.

Figure 2: Plastic Packaging Waste in the European Union, 2009-2019

While grocery stores are a major contributor to food packaging waste, the bulk of it is actually made up of waste from meals to go and restaurant delivery services. The takeaway industry is notorious for generating huge amounts of unnecessary waste. Eateries often wrap their food in aluminium or plastic foil or opt for Styrofoam containers, while beverages often come in their own carrier bags. In addition, most takeaway food comes with plastic cutlery, napkins, and straws. All these single-use plastics and packaging make up nearly half of the ocean plastic, a 2021 study found.

Figure 3: Top 10 Types of Plastic Litter in the Ocean, 2021

Several experts also point out that packaging waste from disposable takeaway containers and cutlery skyrocketed during the Covid-19 pandemic, as restaurants stepped up delivery services during the long months of lockdowns imposed around the world. In Hong Kong – a city with a population of nearly 7.5 million people – the pandemic outbreak in 2020 fuelled the use of more than 100 million disposal plastic items per week as food orders surged 55% compared to 2019 figures. In the US, plastic waste increased by 30% during the pandemic. This extensive increase in plastic consumption has resulted in an estimated 8.4 million tonnes of plastic waste generated from 193 countries since the start of the pandemic, 25,900 tonnes of which – equivalent to more than 2,000 double-decker buses – have leaked into the ocean, according to recent research.

What’s more, the issue with food packaging does not stop with waste generation. To produce plastic food packaging and drink bottles, gases need to be fracked from the ground, transported, and processed industrially, contributing millions of tons of greenhouse gas emissions. A large portion of which is methane, a greenhouse gas that is 25 times as potent as carbon dioxide.

You might also like: Rethinking Sustainable Packaging and Innovation in the Beverage Industry

Comparing Conventional Food Packaging Materials

As we have mentioned before, plastic is by far the most popular food packaging material and yet aluminium, glass, and paper are still widely used. But why is there such a big variety and how do these types of packaging compare to each other?

Plastics

Plastic is not only the most inexpensive and lightweight packaging material on the market, but because of its chemical composition, it can also easily be shaped into different forms and thus accommodate a huge range of food items. While some types of plastic packaging can be reused, styrofoam-like containers – mostly used in restaurants for takeaways and deliveries – are often impossible to recycle because of food contamination. Furthermore, most plastic items are designed for single-use, which makes this material even more problematic.

Furthermore, its production contributes high quantities of pollutants to the environment. For every kilogramme of fossil-based plastic produced, there are between 1.7 and 3.5 kilogrammes of carbon dioxide released into the atmosphere. Plastic production utilises 4% of the world’s total fossil fuel supply, further emitting planet-warming greenhouse gases.

Glass

Glass guarantees protection and insulation for food items from moisture and gases, keeping the product’s strength, aroma, and flavour unchanged. It is also relatively cheap and easily reusable. However, the fact that it is easily breakable, heavy and bulky, and thus costlier to transport, makes it a less favourable alternative to plastics.

Glass containers used in food packaging are often surface-coated to provide lubrication in the production line and eliminate scratching or surface abrasion and line jams. While the coating increases and preserves the strength of the bottle, fossil fuels that drive this process as well as evaporation from the glass itself release polluting particles and CO2 gases into the atmosphere.

Aluminium

Aluminium is a great impermeable and lightweight packaging material, yet it is more expensive, requires hundreds of years to break down in landfills, and is more challenging to recycle than other alternatives because of the chemical processes it undergoes to be laminated, which make material separation an intricate operation.

Aluminium is commonly used to make cans and bags of crisps as well as takeaway items such as trays, plates, and foil paper, but various nonrenewable resources are required to create the material. Its production is the result of mined bauxite that is smelted into alumina through an extremely energy-intensive process that also requires huge amounts of water. Emissions deriving from aluminium production include greenhouse gases, sulfur dioxide, dust, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, and wastewater.

Paper and Paperboard

Despite no longer being the most popular food packaging materials, paper and paperboard are still widespread mainly because of their low cost. However, while there are some great reusable and often biodegradable packaging options, paper containers are nearly impossible to recycle when used to wrap food items. Not only because they lose strength from food condensation, it is also less safe to do so due to food contamination.

Surprisingly, paper requires even more energy to produce than plastic, sometimes up to three times higher. It takes approximately 500 kilowatt-hours of electricity to produce 200kg of paper, the average amount of paper that each of us consumes each year. That is approximately the equivalent of powering one computer continuously for five months. Furthermore, various toxic chemicals like printing inks, bleaching agents, and hydrocarbons are incorporated into the paper during the packaging’s development process. These toxic substances leach into the food chain during paper production, food consumption, and recycling through water discharges.

Innovative Sustainable Food Packaging Alternatives

As we have seen, despite the advantages that make it extremely convenient for food suppliers to use them, some of the most popular food packaging materials are undoubtedly detrimental to the environment. And yet, it is not all bad news.

According to the latest Eco-Friendly Food Packaging Global Market Report, the global sustainable food packaging market is expected to grow from USD$196 billion in 2021 to over USD$210 billion in 2022 and up to USD$280 billion in 2026. Indeed, an increasing number of companies and startups – mostly located in North America – are investing time and resources in the development of alternative packaging materials which are easy to recycle, reuse, compost, or biodegrade and thus have a very minimal environmental footprint.

As is the case in many other sectors, the food industry is undergoing a revolution in terms of finding sustainable solutions to reduce its impact on the environment and meet sustainable consumer demands. Startups and packaging companies have developed incredibly innovative and sustainable solutions to the classic food packaging materials and while they are still used in very small quantities around the world in comparison to glass, plastic, and paper, they have the potential to radically transform the sector.

Some examples include sustainable food packaging made with cornstarch, popcorn, and mushrooms, as well as innovative and biodegradable cutlery, plates, and containers realised with agro-industrial waste such as avocado pits.

EO’s Position: We have all the instruments we need to drastically reduce the detrimental impact of the food packaging industry on the environment. While consumers can do their part by shopping more consciously at grocery stores and bringing reusable containers when getting takeaway food, the situation will not change unless food retailers and restaurants step up the game as well. If we want to cut packaging waste, we need big companies to take the lead and make the necessary switch to more sustainable food packaging alternatives.

The chemicals that linger for decades in your blood

Environmental journalist Anna Turns experienced a wake-up call when she had her blood tested for toxic synthetic chemicals – and discovered that some contaminants persist for decades.In March 2022, scientists confirmed they had found microplastics in human blood for the first time. These tiny fragments were in 80% of the 22 people tested – who were ordinary, anonymous members of the public. The sample size was small and as yet there has been no explicit confirmation that their presence causes any direct harm to human health, but with more research, time will tell.

Microplastics are the subject of a lot of scrutiny. Wherever we look for them we find them. And yet, there are perhaps other less tangible pollutants that should be hitting the headlines, and which have been in our blood for decades.

Chemical pollution has officially crossed “a planetary boundary”, threatening the Earth’s systems just as climate change and habitat loss are known to do. A recent study by scientists from Sweden, the UK, Canada, Denmark and Switzerland highlights the urgent need to turn off the tap at source. Many toxic chemicals, known as persistent organic pollutants, or POPs, don’t easily degrade. They can linger in the environment and inside us – mostly in our blood and fatty tissues – for many years.

I was curious about whether any of these chemicals were in my own blood while researching for my book, Go Toxic Free: Easy and Sustainable Ways to Reduce Chemical Pollution, I contacted a professor of environmental chemistry in Norway called Bert van Bavel. His research has focused on POPs that persist in bodies for more than 20, 30, sometimes 50 years and he analyses how high exposure in populations correlates to cancers, heart disease and conditions such as diabetes.

Bert van Bavel developed a blood test protocol for Safe Planet, a global awareness campaign established by the UN Environmental Programme that could be used to monitor the levels of these toxic chemicals in the global population.

Safe Planet highlights the harm caused by the production, use and disposal of hazardous chemicals such as flame retardants and pesticides, many of which have been banned. He designed a test to measure ‘body burden’ – that’s the amount of these persistent synthetic chemical pollutants that accumulate in the body. Since 2010, this test has been carried out on more than 100,000 people around the world, across Europe, North and South America, Africa and Southern Asia.

Now, it was my turn. I booked an appointment at my local GP surgery and had my blood taken. I carefully packaged up the test tubes and couriered them to a specialist lab in Norway which spent six weeks analysing my blood for 100 or so POPs in line with this body burden test protocol.Much attention has been paid to microplastics in human blood, but there are other chemicals that many of us carry that last for decades (Credit: Getty Images)When the results finally arrived via email, I felt quite apprehensive. The eight-page-long document detailed concentrations of so many chemicals, each with tricky-to-pronounce names. I needed help to decipher what this all meant and to work out if I should be worried about any, or if, perhaps, these levels were low enough to be insignificant.

So I called van Bavel who explained that most of the chemicals on the list were to be expected as part of the “toxic cocktail” we all have in our bodies.

Many, but not all, of these POPs are regulated by the UN’s Stockholm Convention, a global treaty that bans or restricts the use of toxic synthetic chemicals such as certain pesticides, flame retardants and PCBs or polychlorinated biphenyls that were used as cooling fluids in machinery and in electrical goods in the UK until 1981.

“In your blood sample, we looked at the old traditional POPs which have been regulated and off the market so they haven’t been used for many years,” he explained. My results showed traces of DDE, a metabolite of the pesticide DDT that was used until the 1970s as well as low levels of PCBs. “It’s a little bit frightening that if you get these chemicals in society, it’s very difficult to get rid of them.” Despite bans, these chemicals still persist, as many don’t degrade easily.He was surprised to find relatively high levels of a chemical known as oxychlordane which is normally found at lower levels than DDT and more often in the US and Asia than in the UK. The pesticide chlordane was banned in the UK in 1981, just a year after I was born. Once in the body, it’s metabolised into oxychlordane which was found in my blood at only 5% of the levels present in the population during the 1980s. But the ‘half life’ of this chemical – that’s the time it takes for it to halve in concentration in my blood – is about 30 years. So not only was it probably passed to me via the womb, but I will have inadvertently passed this toxic legacy on to my own two children.

The impacts of some of the most hazardous chemicals last generations and chlordane is still used in some developing countries to this day. Chlordane is toxic by design – intended to kill insects, it also harms earthworms, fish and birds. In humans, it can disrupt liver function, brain development and the immune system plus it is a possible human carcinogen. Van Bavel wasn’t alarmed by the current concentrations of oxychlordane still in my blood but he did emphasise the importance of banning toxic chemicals before they become globally prevalent and then accumulate in the human population.

But the chemicals that concerned van Bavel the most were actually from a newer class, known as PFAS or polyfluoroalkyl substances. Thousands of different PFAS chemicals are used in everyday products to repel dirt and water – waterproof clothing, stain-resistant textiles, non-stick cookware all tend to be made with PFAS, otherwise known as “forever chemicals” because they are so persistent.

Should I be worried?

“Your levels [of PFAS] are not that high but they are a reasonable concern. We found ones called PFOS (perfluorooctanesulfonic acid), PFNA (perfluorononanoate), and lower levels of PFOA (perfluorooctanoate) the one we normally find in blood samples. The test found the major ones at ‘a reasonable level’, not a worrying level, but the regulation is lagging behind,” commented van Bavel. He described my body burden as fairly average.

“We’re all exposed to these types of chemicals. They accumulate in our body but they shouldn’t be there. Your levels are acceptable from a human health perspective but if we didn’t have any measures in place, levels would rise and our population would see different toxicological effects. Of course, these chemicals need to be regulated and… the number of replacements is rising so we need proper measures in place [to govern them].”Anna’s Toxic CocktailChlordane (insecticide) – banned in the UK, US and the EU

DDT (insecticide) – banned globally

PCBs (flame retardants, paints, cooling fluids) – banned globally

PFOS (fire-fighting foams, non-stick coatings and stain repellents) – restricted but not banned

PFNA (same as PFOS) – not yet banned

PFOA (same as PFOS) – banned in 2019This “regrettable substitution” or replacement of one banned chemical with another similar one is a worry, especially with new emerging chemical pollutants such as PFAS, as van Bavel explains: “We don’t have time to wait for research on every single chemical so we need to take a precautionary approach.”

In terms of my own body burden, there’s not much I can do to reduce the levels of toxic chemicals in my blood, according to van Bavel. “The sad thing is that it’s very difficult for us to do something about it – we should all be very eager to regulate these compounds because they’re everywhere. It’s very difficult as an [individual] to avoid these background levels that we see that definitely should not be in your body. That’s why we should support legislation and UN conventions that remove these compounds.”Prevention is better than cure

Better legislation is something Anna Lennquist, a senior toxicologist at the environmental NGO ChemSec, campaigns for. Based in Sweden, ChemSec aims to reduce the use of hazardous chemicals by influencing policy makers and encouraging companies to phase these chemicals out and opt for safer alternatives.

“We can reduce exposure but not eliminate it,” agrees Lennquist. According to ChemSec, a huge 62% of the total volume of chemicals used in the EU are hazardous to human health and the environment. “[That’s] why regulations are so critical and should protect us. Normal people shouldn’t need to be bothered by these things – but we’re not there yet.

“We can’t be completely free from this, we have it with us from when we are born and it’s so widespread in the environment – all of us have hundreds of [synthetic] chemicals in our blood these days,” says Lennquist.

Toxic chemicals affect everything from our brain development to our hormone systems. Some can be carcinogenic. “Chemicals are working in many different ways in your body… some chemicals have delayed effects, for example ones that interact with our hormone systems. If you are exposed in the womb or during puberty, the effects can turn up many years later, even decades later, perhaps as breast cancers or different metabolic disorders.”

So the outcomes depend not only on the type and level of exposure, but also whether that person is exposed during key stages of development. Lennquist explains that because we’re never just exposed to one chemical at a time, this ‘toxic cocktail’ effect can be complex. Some chemicals might enhance the effect of others, some can work against each other.

“These low levels of this chemical mixture that affect hormone signalling and genetic effects are much more diffuse and difficult to link exactly – so that’s why we need to do large-scale studies of populations over a long time to try to figure out what’s the cause and what’s the reason,” says Lennquist, who remains optimistic.Firefighters are exposed to higher than average levels of PFAS as it is still used in flame retardants (Credit: Getty Images)New EU restrictions to ban around 12,000 substances have been proposed in what the European Environmental Bureau has called the world’s “largest ever ban on toxic chemicals”, but changes in regulation can be incredibly slow moving. “There is a long way to go but with the new EU chemical strategy and European Green Deal, we are hopeful that things can improve a lot. But even then, that would take a long time before that change is visible in your blood, I’m afraid.”

Labels allow consumers to make a conscious choice without having to understand everything.

That’s where we come in, as consumers, and more importantly, as citizens. “We can all use our voice by demanding greater transparency, clearer labelling and stricter regulation,” adds Lennquist. “With pressure from consumers and everyone else within the supply chain, the chemical manufacturing industry could shift much more rapidly. And reducing toxic chemical pollution is not only good for business, but for every one of us and future generations.”

Blood matters

As a regular blood donor myself, I wondered whether the NHS Blood Donation service tests for POPs like the ones in my body. As expected, they confirmed they screen for diseases such as hepatitis, not synthetic chemicals. Of course, chemical contaminants may well be the last thing on your mind if in need of a blood transfusion, but it got me thinking. Do we need to be more cautious about sharing blood and passing on legacy contaminants? Or is blood donation one way to offload toxics – because the contaminated blood flows out, and the body then produces fresh, uncontaminated blood?

Since publishing my book, new research has been published about just this. Firefighting foams are known to contain high levels of PFASs, so firefighters are exposed to higher than average levels of those chemicals. The landmark trial tested 285 Australian firefighters for PFAS in their blood over the course of one year. Some donated blood, some did not. PFAS chemicals bind to serum proteins in the blood, and researchers found that PFAS levels in the bloodstream of those donating were significantly reduced. One possible explanation is that the donors’ bodies did indeed offload the PFAS-contaminated blood, and replaced it with unpolluted blood.

While it is still early days for this research, the feasibility of blood donation as a longterm, scalable solution is still questionable, as Lennquist explains: “For specifically exposed persons, like firefighters, it may be an option to empty the contaminated blood and let your body produce new blood. That requires that you will not be exposed again. For the average person the exposure is quite constant and I do not see that it could be a solution for the general population. But it definitely points to the urgency to do something about PFAS.”

While removal may well be a crucial step in some cases, surely the most appropriate solution is to turn off the tap at source and prevent PFAS and other toxic chemicals entering our bodies in the first place.

Listen to My Toxic Cocktail, Anna Turns’s investigation for BBC Radio 4’s Costing the Earth series on BBC Sound.

Go Toxic Free: Easy and Sustainable Ways to Reduce Chemical Pollution by Anna Turns is out now.

How contaminants like PFAS and microplastics are being tracked in Connecticut

Microbeads were banned in the U.S. in 2015, but tiny bits of plastic known as microplastics, and another manmade family of chemicals called PFAS, are turning up in our environment and in our bodies. A recent survey conducted by Connecticut Sea Grant identified both materials as “top” contaminants of emerging concern this year.This hour, we hear about efforts to track PFAS and microplastics in Connecticut. Experts at Connecticut Sea Grant and the State Department of Public Health join us to discuss the prevalence and impact of PFAS; and UConn Professor and Head of UConn’s Marine Sciences Department J. Evan Ward touches on microplastics in the Long Island Sound.Plus, Elizabeth Ellenwood is an artist from Pawcatuck whose work draws attention to ocean pollution and microplastics. She was recently awarded a Fulbright Research Scholarship and an American Scandinavian Foundation Grant to travel to Norway, where she’s working with environmental chemists and marine biologists to produce scientifically-informed photographs focusing on ocean pollution.

1 of 5

— Screen Shot 2022-05-11 at 4.13.58 PM.png

Pawcatuck artist Elizabeth Ellenwood uses scientific methods for her “Sand and Plastic Collection” series. She says the goal is to “create visually engaging imagery with scientific materials to give viewers an entry point into microplastics research.”

Elizabeth Ellenwood

2 of 5

— _DSC0045.jpg

“Line & Seaweed” – Korsvika, Trondheim Norway 2022

Elizabeth Ellenwood

3 of 5

— _DSC0008.jpg

“Wrackline” – Korsvika, Trondheim Norway 2022

Elizabeth Ellenwood

4 of 5

— Bottle_.jpg

“Bottle (collected from GSO Pier)” – Narragansett RI USA 2021

Elizabeth Ellenwood

5 of 5

— Trash_GSOPierDive_Narragansett_RI_7_29_210302.jpg

“Bottle Piece (collected from GSO Pier)” – Narragansett RI USA 202

Elizabeth Ellenwood

GUESTS:J. Evan Ward: Professor and Head of Marine Sciences Department, University of ConnecticutSylvain De Guise: Director, Connecticut Sea Grant at UConn Avery PointLori Mathieu: Drinking Water Section Chief, Connecticut Department of Public HealthElizabeth Ellenwood: Artist