Two years ago, efforts to kick the country’s plastic addiction were on fire. Municipalities around the country were implementing plastic bag taxes, while mainstream shoppers embraced reusable grocery bags and flocked to the bulk aisles for foods like beans and nuts.However, all that came to a halt when stopping the spread of COVID-19 became the country’s top priority. Almost overnight, grocery stores closed their bulk-shopping sections, coffee shops stopped filling reusable coffee mugs, and individually wrapped everything took center stage.Now, signs are emerging that the fight against plastic is getting back on track. One of the most notable of those signs came from Kroger last month, when the nation’s largest grocery chain announced it was expanding an online trial with Loop, an online platform for refillable packaging, to 25 Fred Meyer store locations in Portland, Oregon.While consumer reuse models “got punched in the face” by the pandemic, Loop’s Tom Szaky said the demand is still there, and mainstream grocery stores are going to need to find a way to meet it.Kroger plans to offer a separate Loop aisle in these stores. The products, which will include a mix of items in food and other categories, can be bought in glass containers or aluminum boxes. When they’re empty, customers return the containers to the store to be cleaned and used again. Originally scheduled for this fall, the launch has been postponed to early 2022 because of supply chain challenges, but a spokesperson said they will continue to work with their brand partners to consider items that can be added to expand the program over time.The partnership is a heartening sign after a tough year, said Tom Szaky, CEO and founder of TerraCycle, the company behind the Loop initiative. “Overall, I was very worried that the pandemic would shift the conversation away from waste,” Szaky told Civil Eats. “It didn’t slow down. In fact, the environmental movement’s only gotten stronger.” While consumer reuse models—reusable grocery bags, refillable coffee mugs—“got punched in the face,” he said, it was mainly because retailers stopped allowing them for safety reasons.And while Loop’s growth was slowed by the pandemic, it was for the same factors that upended many companies’ plans—not because interest was drying out, said Szaky. The demand is still there, he adds, and he’s bullish on the idea that mainstream grocery stores are going to need to find a way to meet it.The Kroger–Loop partnership could be the first true test of this theory. It’s the latest in a steady string of new partnerships for Loop, but until now all of the company’s U.S. packaging partners have been in other categories, such as cosmetics and cleaning products. Loop does work with a number of food companies outside the country, including Woolworths in New Zealand, Tesco in the U.K., Aeon in Japan, and Carrefour in France. Szaky says they’re also working with a grocery store in France to bring reusable packaging to fish and meat. Loop, which also works with Walgreens in the U.S. and fast food chains McDonald’s, Burger King, and Canada-based Tim Hortons, expects nearly 200 stores and restaurants worldwide to be selling products in reusable packages by the first quarter of 2022, according to the Associated Press, up from a dozen stores in Paris at the end of last year. Some experts in the space are convinced that more will follow.“It’s just a matter of time before other companies come on board,” says Colleen Henn, founder of All Good Goods, a plastic-free pantry subscription business based in San Clemente, California that sells food in reusable glass jars and paper bags. “Once somebody does it, people start to see, ‘Oh, avoiding single-use plastic is] not that complicated.’ Because it’s really not.”She would know. Henn didn’t spend the last year adapting her business; she first launched her seemingly improbable business model during—and really because of—the pandemic. She had grown frustrated that the country’s waste-reduction initiatives were falling by the wayside. “I went online and tried to find a store that shipped food to your door without plastic, and I couldn’t find it. So I created it,” said Henn.All Good Goods specializes in pantry goods like beans and pasta, nuts and dried fruit, and growth has been strong and steady since the launch. She increasingly fields phone calls from other stores looking for advice on how to avoid plastic in their operations, and as she engages with more companies, she’s optimistic that she will have a trickle-up effect within the industry. “I reach out to brands [we’re considering carrying] and see what their wholesale options are; if they’re not paper-based, if they’re not backyard-biodegradable, we move on,” said Henn.

Category Archives: Land

Most of us think supermarkets are responsible for plastic pollution

A pile of household waste at a landfill.Most people believe supermarkets and manufacturers are to blame for plastic pollution, a survey has found. In 2019, UK supermarkets produced 896,853 tonnes of plastic packaging – a slight decrease of less than 2% from 2018, according to Greenpeace.Supermarkets such as Waitrose have reduced plastic use and committed to increasing reusable packaging and unpacked ranges.But a survey by retail app Ubamarket found that most British shoppers think not enough is being done.Researchers found that 82% of shoppers believe the level of plastic packaging on food and drink products needs to be changed drastically.Read more: A 1988 warning about climate change was mostly rightMeanwhile, 77% believe that it is supermarkets and manufacturers that are causing the most plastic pollution, while 57% think that plastic pollution is the greatest threat to the environment.Will Broome, CEO and founder of Ubamarket, said: “While supermarkets have a long way to go, it is encouraging to see the use of single-use plastics beginning to be reduced in the UK.”This is helping us as a society take major steps towards creating a more sustainable future for the food retail sector, and retail across the board.”It is imperative that other retailers take heed of this and work quickly to establish their own sustainability goals and action plan.”Implementing mobile technology is one effective way for retailers to get ahead of the curve – not only can it improve in-store efficiency and provide access to useful data for the retailer.”Read moreWhy economists worry that reversing climate change is hopelessMelting snow in Himalayas drives growth of green sea slime visible from spaceBroome said Ubamarket’s Plastic Alerts feature allows users to shop “according to the recyclability and environmental footprint of different products, and enables the customer to scan packaging for information on whether it can be widely recycled or not”.Story continuesResearch published earlier this year found that thousands of rivers, including smaller ones, are responsible for 80% of plastic pollution worldwide.Previously, researchers believed that 10 large rivers – such as the Yangtze in China – were responsible for the bulk of plastic pollution. In fact, 1,000 rivers, or 1% of all rivers worldwide, carry most plastic to the sea.Therefore, areas such tropical islands are likely to be among the worst polluters, the researchers said.Watch: Philippine recyclers turn plastic into sheds

Provocative eco-art exhibition in S.F. forces confrontations with climate change

Sea levels may be rising, but Ana Teresa Fernández and her bucket brigade are doing what they can to combat it.Forming a 200-yard human chain on Ocean Beach, they drew 170 gallons out of the surf, hauled the sloshing saltwater off the beach and up to the old Cliff House restaurant, where it was carried into the dining room and muscled up a ladder to be poured into seven clear cylinders, all six-feet tall.

Living on Earth: Beyond the Headlines

Air Date: Week of November 5, 2021

stream/download this segment as an MP3 file

Some cement factories are collecting plastic waste from consumer goods businesses and landfills to use as fuel to fire their kilns, posing the risk of polluting air with toxic chemicals. (Photo: Xopolino on Wikimedia Commons)

This week, Host Bobby Bascomb talks with Peter Dykstra, an editor at Environmental Health News, about the public health hazards of cement kilns burning plastic waste as a source of fuel. And in California, Scripps Institution of Oceanography is building a 32,000-gallon simulated ocean to study the effects of climate change. Also, a trip back in time to November 1492 when native peoples introduced Christopher Columbus and his expedition to maize, which became a major food staple across the globe.

Transcript

BASCOMB: It’s time for a trip now Beyond the Headlines with Peter Dykstra. Peter’s an editor with Environmental Health News, that’s ehn.org, and DailyClimate.org. Hey there, Peter, what do you have for us this week?

DYKSTRA: Hi, Bobby. There’s an investigative story from Reuters. They’ve looked into cement kilns, cement kilns are everywhere, especially in booming cities in the developing world. They’re responsible for 7% of all the greenhouse gases emitted. So that’s a huge chunk. And right now, those cement kilns are looking for a new source of fuel to fire up the kilns and they’ve hit upon plastic waste. And that can be a bigger problem than any problem they may be solving.

BASCOMB: Hmm. Well, that makes sense. I mean, plastic is made with fossil fuels. So it’s, you know, pretty energy rich and there’s so much plastic waste out there. It’s free, or maybe even in some places might pay to have it, you know, burned like that. But of course, you know, it’s not too good for air quality now, is it?

DYKSTRA: Right, and there are consumer firms that are funding projects to send their plastic trash to cement plants. It’s a dangerous idea, given the amount of carcinogenic fumes that exists in those plastics, now burning straight, from, in many cases, the developed world to the developing world, to all of our lungs.

Cement factories are burning plastic to fire up massive cement kilns like the one pictured here. (Photo: LinguisticDemographer on Wikimedia Commons)

BASCOMB: Yeah, I mean, looking at things like dioxins, heavy metals, carcinogens. I mean, it’s pretty, pretty toxic stuff.

DYKSTRA: And it’s been said that burning plastics in cement kilns doesn’t help lessen the landfill problem. It simply transfers the landfills from being on the ground to in the skies.

BASCOMB: Well, that certainly is a big problem. Well, what else do you have for us this week Peter?

DYKSTRA: It’s kind of a weird sci-fi sort of project. The Scripps Institute out in San Diego is building a 32,000 gallon tank that has a wind tunnel on top of it. And with all that, they hope to synthesize what happens in the ocean, and how the oceans can affect climate change.

BASCOMB: How will they do that?

DYKSTRA: There are wind currents brought in, water currents introduced mechanically into this tank, and we’ll see what happens as climate change begins to alter both wind and wave and current patterns. It’ll give a little bit more of an insight as to what lies ahead in our future, as climate change really takes hold in our oceans.

The surface layer of the ocean can tell scientists a lot when looking at climate change. That is one aspect researchers at Scripps Institution of Oceanography will study in their simulated ocean. (Photo: NOAA on Wikimedia Commons)

BASCOMB: So they can simulate climate change in this pool and sort of speculate what we’re going to be looking at then.

DYKSTRA: Right, and thanks for using the word pool because 32,000 gallons sounds like a lot, but it’s actually about 5% of what it takes to fill in a competition sized Olympic swimming pool.

BASCOMB: So it’s really not all that big then. It’s amazing what they can do in such a small space.

DYKSTRA: It is. Scientists can have fun with it and can give us some information that’ll help guide us through a particularly dangerous time in our environmental future.

BASCOMB: Indeed, well, what do you have for us from the history books this week?

DYKSTRA: November 5, 1492. And we all know what happened in 1492. Columbus sailed the ocean blue. And on his subsequent stop to the Bahamas, Columbus went to Cuba in early November, and he was introduced to maize. That corn was brought back to Europe and has since become a global staple for both humans and livestock.

BASCOMB: Well, yeah, there’s so much to that. I mean, that the Columbian Exchange brought tomatoes and potatoes to Europe. I mean, imagine Italian food without tomatoes, but before that, they made do I guess.

Maize has become a food staple around the world after it was introduced from the New World to the Old World in 1492. (Photo: Balaram Mahalder on Wikimedia Commons)

DYKSTRA: And even though Columbus was a tip of the spear, coming from Europe, in the genocide of native peoples in the West, one other thing that was a gift so to speak, from North America to Europe was of course, tobacco. So it’s feed ya and kill ya, Mr. Columbus.

BASCOMB: All right. Well, thanks Peter. Peter Dykstra is an editor with Environmental Health News. That’s ehn.org and DailyClimate.org. We’ll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: Okay, Bobby. Thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

BASCOMB: And there’s more on these stories on the Living on Earth website. That’s loe dot org.

Links

Reuters | “Trash and Burn: Big Brands Stoke Cement Kilns with Plastic Waste as Recycling Falters” WIRED | “This Groundbreaking Simulator Generates A Huge Indoor Ocean” Read more about the Columbian Exchange

The trash divers protecting America’s best-loved lakes

“My girlfriend tells me I smell like trash,” says Colin West. And he takes that as a compliment.

West spends 40 to 60 hours a week scuba diving Lake Tahoe to locate and remove submerged trash. On the day I spoke with him, he and a group of divers had collected 576 pounds of underwater garbage, including a massive monster truck–style tire. And since launching the nonprofit Clean Up the Lake in 2018, West and his team of ten full-time employees and contractors, plus an army of trained volunteers, have picked up more than 18,000 pounds of refuse.

Their latest mission? To complete the first circumnavigation of Lake Tahoe via scuba diving, with each dive focused on removing waste. As the nonprofit’s founder and executive director, West dives for trash three days per week, ten to 12 hours each dive, alongside a crew of Clean Up the Lake employees and volunteers.

The group’s Tahoe initiative launched in 2020; it’s supported by local sponsors like Tahoe Blue Vodka and the Tahoe Fund and will cover the waterway’s 72-mile circumference. It’s among the largest litter-removal efforts ever for the lake, and it couldn’t come at a better time. While lauded for its bright-blue beauty, Lake Tahoe’s deep-water clarity has plummeted by 30 percent from 1968 to 1997, according to the EPA. In 2019, scientists also found microplastics in Lake Tahoe’s water for the first time—a fact that’s particularly troubling given that the lake is a major drinking water source for Nevada communities.

Even with forces out of their control—the 221,000-acre Caldor Fire in fall 2021 and severe droughts impairing water access—West anticipates his crew will complete the circumnavigation this December. Along the way, Clean Up the Lake has done much more than rid Tahoe of litter. West is giving legs to a budding “give back while getting outside” movement: trash diving. (Think plogging but fully underwater.)

Trash collection isn’t new to the world of scuba. Since 2011, divers have removed more than 2 million pieces of marine debris through the Professional Association of Diving Instructors’ (PADI) Dive Against Debris program, a global scuba initiative to remove and log submerged litter, says Kristin Valette Wirth, PADI chief brand and membership officer.

In recent years, though, diving for waste has expanded inland to the country’s best-loved yet increasingly polluted lakes. West alone has received approximately 600 applications from interested scuba volunteers around Lake Tahoe. The Great Lakes also have trash divers tackling the region’s growing water-contamination concerns. These lakes, which make up more than 20 percent of the planet’s surface freshwater, are polluted with 22 million pounds of plastics each year, largely from local watersheds and shorelines.

(Photo: Professional Association of Diving Instructors)

Lake Tahoe and the Great Lakes may lack the colorful corals and enchanting marine life of the oceans, but these under-the-radar dive locales offer two main allures: mind-blowing geology and rarely seen shipwrecks. The Great Lakes alone boast more than 6,000 sunken ships.

“We have the best shipwreck diving in the whole world, hands down,” says Chris Roxburgh, one of the Great Lakes’ best-known divers. Roxburgh, a master electrician in Traverse City, Michigan, reached local diving fame through his jaw-dropping photos of Great Lakes wrecks. This fall, he appeared on the History Channel’s Cities of the Underworld to share this wreck beauty with the world.

Social media helps Roxburgh and dozens of area divers showcase the hidden wonders of Great Lakes scuba while illustrating the severe plastic plight lurking below the surface. Roxburgh’s home waterway, Lake Michigan, receives roughly half of all of the Great Lakes plastic pollution. With everything the Great Lakes have given him, both recreationally and professionally, Roxburgh now feels responsible for protecting and future-proofing these waterways. He shares footage of submerged Mylar balloons, wrappers, toys, and soda cans to inspire followers to get involved.

“Since I was a kid, my parents taught me to leave no trace and clean up trash along the beaches and underwater, so it’s something I’ve been doing my whole life,” he says, noting that local wreck-diving fame has given him a platform to fight for the lakes he loves. “I felt like I needed to put [content] out there to show people they can make a difference. Especially scuba diving. We get the trash people can’t get to.”

(Photo: Chris Roxburgh)

Some area divers, like “Diver Don” Fassbender of Great Lakes Scuba Divers and Lake Preservation Club, host trash-diving meetups in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. But Roxburgh typically goes with a small, hand-selected group, due largely to the liability and dangers, which are increased by the often-required clunky drysuits.

“If you don’t do it properly, your trash bag can get snagged, and it can become entangled in your equipment,” Roxburgh says. “The main thing is to not collect too much to the point it makes the dive unsafe. Always have a plan on how much you’re willing to collect safely, and don’t have ropes or strings floating about.”

Diving Lake Tahoe comes with its own unique risks. It’s the second-deepest lake in the world (1,600 feet) and sits at an altitude of around 6,200 feet above sea level. These elements make for tricky dive safety, and that’s before adding the variable of collecting garbage. West says Clean Up the Lake requires volunteers to have “at least advanced open-water certification with five recent dives.” Each new volunteer goes through rigorous preparation. So far, his team has selected and trained just under 100 volunteers.

“They need to be comfortable when working in a team underwater, because we’re down there working,” he says. Each team of divers—two scuba, one freediving near the surface—follows GPS coordinates. The scuba divers take mesh bags to pick up small trash along the way and use custom hand signals with the freedivers if they stumble upon something heavy that requires a weighted rope system.

Then there’s the fact that they’re diving well beyond summer to meet that December 2021 goal. “The winters get f-ing cold, and the lake gets really cold, even in a drysuit,” West says.

(Photo: Chris Roxburgh)

Divers alone aren’t going to clean up 22 million pounds of Great Lakes plastic. And a 72-mile circumnavigation may rid Lake Tahoe of debris—they’ve already removed 8,000 pounds of trash through this circumnavigation initiative—but it’s not going to fix the main Tahoe pollutants: fertilizers and urban stormwater runoff.

Is the risk of trash diving worth the reward? Yes, says Meagen Schwartz, who studied environmental science at Indiana University and founded Great Lakes Great Responsibility (GLGR), a volunteer movement to de-litter the region’s coasts and waterways. GLGR’s newest push, the #GreatLakes1Million challenge, calls on area residents to gather and record litter, then share their work on social media to catalyze local communities. The goal is to pick up 1 million pieces of waste; they’ve collected 90,000 since November 2020.

Schwartz lives in Alpena, Michigan, home to one of the region’s most vibrant dive spots: Lake Huron’s Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary, which boasts nearly 100 historic shipwrecks. While she doesn’t dive herself, Schwartz says trash divers have been instrumental not just to her movement, but to the plastic problem plaguing waterways around the world.

“They’re on the front lines. They’re seeing what’s in the more benthic region [the bottom] of the lake,” Schwartz says. “It’s also about raising awareness about the plastic problem. People can make individual changes, but it really needs to come from putting different legislation in place.”

Schwartz plans to use those 1 million pieces of inventoried trash to fight for change upstream, including data-driven petitions for new, more sustainable legislation. West hopes to do the same; Clean Up the Lake already has hard data from more than 80 categories of collected trash to showcase main pollutant sources and systemic problems.

Making real change is no pipe dream, and PADI’s Dive Against Debris program is proof of that. Take the small island nation of Vanuatu in the South Pacific as a case study. In 2018, Vanuatu decided to ban nonbiodegradable plastic bags, largely based on Dive Against Debris data. The trickle-down effect was monumental.

“Vanuatu no longer required bags to be shipped there, reducing the country’s overall carbon footprint,” says PADI’s Valette Wirth, noting the removal of plastic bags sparked the need for new, sustainably made sacks. Through this community-driven microeconomy, Vanuatuan people created bags using banana and palm leaves. “Due to the success of the policy decision, Vanuatu became a champion country promoting international cooperation to tackle marine debris. This is living proof of how local action can have a global impact.”

Students tackle microplastic issues on Lake Michigan beaches

Avril E. Wiers, Careerline Tech CenterStudents in Careerline Tech Center’s Natural Resources and Outdoor Studies program are exploring the issue of microplastics, hard plastic fragments that are smaller than 5 millimeters across.Microplastics are ingested by wildlife and can end up in our food system where they leach harmful chemicals that can cause hormone disruption and cancer.Samples were collected from six beaches along the lakeshore of Ottawa County, from Grand Haven State Park to Holland State Park, with the state park beaches having the highest concentrations of microplastics.“You don’t really notice (plastic) when you go to the beach, but when you are looking for it, there is a lot everywhere. It’s kind of sad because it’s a beautiful place,” said Eli Steigenga, a student in the program.“I was actually really surprised by the amount of small plastic I found that looked like sea shells,” added Lily DeGroot, another student.Using the data they collected, students in both the morning and afternoon sessions of the program are engaging in a civic actions project to reduce the concentrations of microplastics. The morning session is focusing their attention on nurdles, which are tiny plastic pellets that are used as a raw material for plastics manufacturing.“I was surprised by how much plastic there actually is. You don’t notice it unless you are really looking for it. The amount of nurdles is insane!” one student said.The afternoon session is focusing their efforts on increasing recycling efforts at beaches. In general, Michigan has an average recycling rate of 18 percent, according to the Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes and Energy, well below the nationwide average of 32 percent.Plastic in the environment does not biodegrade; it just breaks down into smaller pieces. That’s why it’s so important for plastics to be recycled properly.“If plastic doesn’t end up on the beaches, it can’t break down to microplastics,” student Aubrey Sibble explained.Students will continue refining their civic action projects by connecting with community businesses and organizations. At the completion of the module, students will present their work and celebrate their learning.“Throughout the project-based learning module, we’ve practiced collaboration and teamwork a lot. We’ve also learned how to communicate professionally with business partners,” Ava Carnevale reflected.The project-based learning module was inspired by the Inland Seas Education Association’s Great Lakes Watershed Field Course, a professional development opportunity to include student-led stewardship actions in their classrooms.Since 2016, this workshop has created Great Lakes stewards of over 100 teachers who, in turn, inspire curiosity through student-led stewardship actions in their classrooms. For more information on the Field Course program, visit schoolship.org/glwfc.The Natural Resources & Outdoor Studies program is a one-year career and technical program designed to introduce students in Ottawa County to the diversity of careers in natural resources, sustainability, environmental science, and recreation. To find out more about program enrollment, visit oaisd.org/ctc or talk to your student’s school counselor.— Avril E. Wiers is an instructor in the Natural Resources and Outdoor Studies program at the Ottawa Area Intermediate School District’s Careerline Tech Center.About this seriesThe MiSustainable Holland column is a collection of community voices sharing updates about local sustainability initiatives.This Week’s Sustainability Framework ThemeEnvironmental Awareness/Action: Environmental education and integrating environmental practices into our planning will change negative outcomes of the past and improve our future.

These silky threads biodegrade in ocean water

Look up images of ocean pollution and you’ll find islands of plastic items like cups, plastic bags, and other single use items. But microfiber from our clothing is also accumulating throughout the environment, and especially in our oceans and freshwater. According to one 2016 report, the fibers are not only ending up in our water supply—they are found in fish and other marine life too. A 2021 study found microfibers in the stomach of a deep sea fish that lives in a remote part of the South Atlantic Ocean, highlighting just how bad the microfiber pollution is around the world.

More than 70 percent of textiles used in the U.S. ends up dumped in a landfill or burned instead of recycled. Threads from the washing machine or a landfill then eventually make their way to waterways.

Enter sustainable fabrics. One company in particular, Lenzing, an Austria-based sustainable fiber producer that developed TENCEL, which are fibers that biodegrade rapidly in comparison with other regularly used fibers like polyester, creates fiber from raw material from wood. The plant base makes the fabric compostable, and materials are from a sustainably managed forest.

[Related: The secret to longer-lasting clothes will also reduce plastic pollution.]

“We take wood from sustainable forestry and use a highly efficient system of processing all raw materials to produce fibers that are able to return to the ecosystem at the end of their life cycle”, said Robert van de Kerkhof, a member of the managing board at Lenzing Group via a press release. “The textile and non woven industries have to change. Our goal is to raise widespread awareness of major challenges such as plastic pollution.”

The relatively easy rate of breakdown could be crucial for ocean waste if more manufacturers lean on using biodegradable materials instead of synthetic fabrics that create microfibers. Researchers with the University of California’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography in San Diego tested the fibers and published a study in October highlighting how the wood-based material was able to biodegrade quickly in the ocean.

The scientists placed clothing made from synthetic material, like polyester in seawater for more than 200 days. Over the course of the soaking period, scientists did not observe any biofilm or biodegradation—the polyester clothes slowly broke down into plastic microfibers in the water.

“Plastics then undergo processes of fragmentation or deconstruction into smaller pieces… “[These materials] may take anywhere from decades to centuries for most types of plastic [to breakdown’,” the study’s authors wrote.

[Related: Bamboo fabric is less sustainable than you think.]

However, clothing made from Lenzing’s TENCEL fibers were placed in seawater for only 21 days and showed signs of breaking down in the water including a biofilm around the material as it began to degrade.

This TENCEL clothing did not create the same microfibers when broken down– the researchers predicted that it would break down entirely in the water within just a few months.

The researchers pointed out that though using recycled plastic to make new clothing is a short term solution to plastic pollution, they worried that the constant introduction of plastic into the country’s waterways would only contribute more to the plastic microfibers in the environment, polluting drinking water and clogging the digestive tracts of sea animals.

“Arguably,” the authors write, “the negative impacts of microfibers accumulating in the environment may outweigh the impact that the larger plastic item could have otherwise had.”

Massive Louisiana plastics plant faces 2+ year delay for tougher environmental review

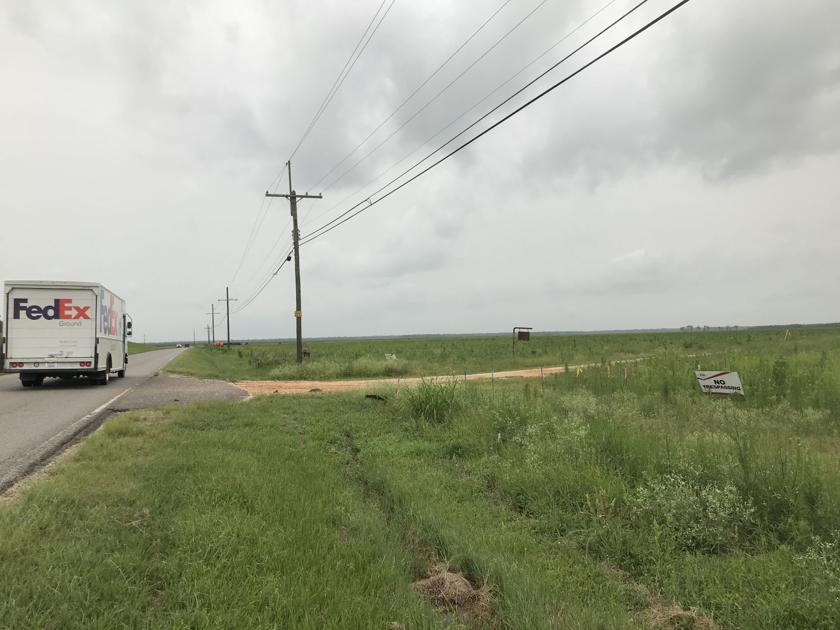

A new, more stringent review of the environmental impacts of a massive proposed plastics plant along the Mississippi River in St. James Parish will likely take more than two years.Environmental groups are cheering that scrutiny, arguing it could provide a more realistic assessment of the environmental damage the plant would do to an area they say already bears a heavy burden of pollution. But some local government and business leaders are trying to rally support for a project that could create about 1,200 permanent jobs and pour millions of dollars into the local economy.The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers had already approved permits for the Sunshine Project, a $9.4 billion plastics plant that Formosa has been trying to build for three years, but it rescinded them a year ago. Environmental groups filed a lawsuit claiming the environmental study was inadequate, and the Corps acknowledged errors.Now the Corps of Engineers is conducting a more thorough review called an “environmental impact statement.” It’s only the fourth such review the New Orleans district of the Corps has conducted since 2008.Martin Mayer, the Corps of Engineers’ regulatory chief in New Orleans, said the EIS process has “an average goal” of rendering a decision in two years. It will involve multiple opportunities for public input so that no “stone goes unturned,” he said.”I mean really the goal of the EIS is to get everybody’s input,” Mayer said.The review means construction on the project won’t be starting anytime soon. The clock on that two-year estimate isn’t likely to start until the spring when a public notice is expected to be published.The Corps still needs to reach an agreement with FG LA LLC, the Formosa affiliate behind the project, on the scope of the work. FG also needs to hire a contractor to do the analysis under the Corps’ direction.’On the wrong side of history’Dubbed the “Sunshine Project” and located just downriver of the Sunshine Bridge, the plant would make pellets and other raw materials that are used to make everyday plastic products. Many state and local leaders have praised its potential economic benefits: It is expected to create 1,200 permanent jobs, thousands more temporary construction jobs and generate tens of millions of dollars in tax revenue.But the plant has triggered lawsuits and regular protests from a dedicated group of local residents and environmentalists. It has also drawn attention from out-of-state political leaders and the United Nations.Critics have claimed that Formosa’s toxic emissions would land on already overburdened Black communities, like Welcome and Romeville, in the Mississippi River corridor. They also argue it would create a massive new source of greenhouse gases at a time when much of the world is trying to fight climate change.The plant would also be built near a graveyard suspected of holding former slaves and become a major new source of the kind of disposable plastics already fouling the Mississippi, the Gulf of Mexico and the world’s oceans, these critics add.

Laska Paré finds a greener flipside to plastic coffee cup lids

As part of a series highlighting the work of young people in addressing the climate crisis, writer Patricia Lane interviews Laska Paré who creates beautiful and useful items from recycled plastic.Laska ParéLaska Paré turns coffee cup lids into soap dishes. No — she’s not a magician. This 33-year-old entrepreneur started Flipside Plastics as a circular economic enterprise, recycling plastics on Vancouver Island. Get top stories in your inbox.Our award-winning journalists bring you the news that impacts you, Canada, and the world. Don’t miss out.Tell us about your project.About $8 billion a year worth of plastic is thrown into landfills and will remain there for millennia. Flipside Plastics is a pilot project to see if we can interrupt plastic’s common life cycle of use-waste-pollute with a model of endless reuse, so it is never wasted and, therefore, never pollutes. We started very small in the spring collecting the lids of disposable coffee cups, shredding and washing them, and turning them into well-designed soap dishes. We have more orders for the soap dishes than we can fill and are now looking to scale up. What people are reading Before Laska Paré found a suitable workspace, she was teaching herself injection moulding in her condo. Photo by Jasper ParéWhat inspired you in this direction?I was distressed by the daily garbage buckets full of disposable coffee cups and lids at my previous workplace. I started a campaign, which I called “Mugshot,” encouraging my colleagues to “kill plastics” by taking a “mugshot” of themselves with their own cup. When I started my own business, I wanted to contribute to a healthier planet. Then COVID-19 hit, and we could no longer use our own cups for take-out. The waste really bothered me. Paper coffee cups can be recycled. I wondered if we could recycle lids.I needed something small to test the idea that we could remove plastic already in our economy from the waste stream. Coffee cup lids are easily washed, lightweight, and small, making the reuse process easier. With the help of a grant from the British Columbia government, I hired a small team and arranged for a volunteer to use his cargo bicycle to collect coffee cup lids from four local Victoria coffee shops. We shred and wash them and when market research revealed interest in well-designed, premium-priced soap dishes, we started to make them from recycled plastic. We are now at the sales end of the first year of our business and have a shortage of source plastic to meet the demand. Coffee shops really like these products because they are able to reassure customers concerned about plastic waste. Coffee consumers using disposable cups find them reassuring, too. Laska Paré turns coffee cup lids into soap dishes. No, she’s not a magician. This 33-year-old started Flipside Plastics as a circular economic enterprise, #recycling #plastics on Vancouver Island. Taking a break in one of the buckets on the bike trailer used to collect the plastic coffee lids from Victoria cafes. Photo by Braedan DrouillardWhat is next?Scaling up might mean more specialization. I might outsource the collection and use recycled reusable plastic pellets. I don’t know the final products yet, as market research is underway, but there seems to be potential in things people see every day, such as coasters, high-end bath kit sets, or small pieces of multi-use furniture that would let them see a sustainable future is possible with their help.What makes your work hard?I cannot sign a standard five-year lease when I have not yet proved my concept and I must locate my machines in areas zoned for light industry. There is very little space available for small manufacturers and it is fiercely expensive. Politicians, bureaucrats, customers, and suppliers are supportive. But when the rubber hits the road, the changes are alarmingly slow. What gives you hope?My volunteers are senior business people who really believe in this concept. My staff is so passionate and driven and we are all so determined to succeed. Their tenacity is infectious. I am participating in a business accelerator program run by the federal government and that is encouraging. We will figure it out.What drew you into this work?I grew up in a small town — Strathroy, Ont. The community had a shared ethic of borrowing rather than buying, and as one of four kids in a single-earner household, we mended and made do. My mom was a genius at repurposing garage sale finds and making art out of junk. Avoiding a high-waste consumer lifestyle is part of who I am. When she is not working, Laska can be found outside adventuring … and picking up plastic waste. Photo by Jasper ParéWhat worries you?The usual uncertainties of starting a small business have been magnified by COVID lockdowns and the cost of everything skyrocketed with the breakdowns in supply chains. But these concerns are all the more reason for us to learn to stop wasting. Think of the good we could do with that $8 billion if it did not go into the landfill and pollute. Do you have any advice for young people?Trust your ideas, especially if you can’t shake them. There were lots of logical reasons for me to not do what I am doing. I kept thinking, “Someone else can do that.” But the concept just stuck to me. Here I am. I have learned so much and every day I make mistakes and learn more. My skill set is so much richer than it would have been. I am very happy.What would you like to say to older readers?Recycled products often carry a premium price, and it is tempting just to go for the cheaper option. But not paying the true cost of our stuff is one of the main ways we got into this mess. You can begin to change that now. We can either pay now or future generations will pay much more dearly.

Trash and burn: Big brands' new plastic waste plan

The global consumer goods industry’s plans for dealing with the vast plastic waste it generates can be seen here in a landfill on the outskirts of Indonesia’s capital, where a swarm of excavators tears into stinking mountains of garbage.

These machines are unearthing rubbish to provide fuel to power a nearby cement plant. Discarded bubble wrap, take-out containers and single-use shopping bags have become one of the fastest-growing sources of energy for the world’s cement industry.

The Indonesian project, funded in part by Unilever PLC , maker of Dove soap and Hellmann’s mayonnaise, is part of a worldwide effort by big multinationals to burn more plastic waste in cement kilns, Reuters has detailed for the first time.

This “fuel” is not only cheap and abundant. It’s the centerpiece of a partnership between consumer products giants and cement companies aimed at burnishing their environmental credentials. They’re promoting this approach as a win-win for a planet choking on plastic waste. Converting plastic to energy, these companies contend, keeps it out of landfills and oceans while allowing cement plants to move away from burning coal, a major contributor to global warming.

Reuters has identified nine collaborations launched over the last two years between various combinations of consumer goods giants and major cement makers. Four leading sources of plastic packaging are involved: The Coca-Cola Company, Unilever, Nestle S.A. and Colgate-Palmolive Company. On the cement side of the deals are four top producers: Switzerland’s Holcim Group, Mexico’s Cemex SAB de CV , PT Solusi Bangun Indonesia Tbk (SBI) and Republic Cement & Building Material Inc, a company in the Philippines.

These projects span the world, from Costa Rica to the Philippines, El Salvador to India. In Indonesia, for instance, Unilever is partnering with SBI, one of that country’s largest cement makers.

The alliances come as the cement industry – the source of 7% of the world’s carbon dioxide emissions – faces rising pressure to reduce these greenhouse gases. Consumer brands, meanwhile, are feeling the heat from lawmakers who are banning or taxing single-use plastic packaging and pushing so-called polluter-pays legislation to make producers bear the costs of its clean up.

Critics say there’s little green about burning plastic, which is derived from oil, to make cement. A dozen sources with direct knowledge of the practice, among them scientists, academics and environmentalists, told Reuters that plastic burned in cement kilns emits harmful air emissions and amounts to swapping one dirty fuel for another. More importantly, environmental groups say, it’s a strategy that could potentially undercut efforts spreading globally to boost recycling rates and dramatically slash the production of single-use plastic.

Such thinking is naive, said Axel Pieters, chief executive of Geocycle, the waste-management arm of Holcim Group, one of the world’s largest cement makers and partner with Nestle, Unilever and Coca-Cola in plastic-fuel ventures. Pieters told Reuters that burning plastic in cement kilns is a safe, inexpensive and practical solution that can dispose of huge volumes of this trash quickly. Less than 10% of all the plastic ever made has been recycled, in large part because it’s too costly to collect and sort. Plastic production, meanwhile, is projected to double within 20 years.

“Thinking that we recycle waste only, and that we should avoid plastic waste, then you can quote me on this: People believe in fairy tales,” Pieters said.

Unilever would not comment specifically on the Indonesia project. It said in an email that in situations where recycling isn’t feasible, it would explore “energy recovery initiatives.” That’s industry parlance for burning plastic as fuel.

Coca-Cola, Unilever, Colgate and Nestle did not respond to questions about the environmental and health impacts of burning plastic in cement kilns. The companies said they invest in various initiatives to reduce waste, including boosting recycled content in their packaging and making refillable containers.

Cemex, SBI, Republic Cement and Holcim’s Geocycle unit told Reuters their partnerships with consumer goods firms were aimed at addressing the global waste crisis and reducing their dependence on traditional fossil fuels.

Exactly how much plastic waste is being burned in cement kilns globally isn’t known. That’s because industry statistics typically lump it into a wider category called “alternative fuel” that comprises other garbage, such as scrap wood, old vehicle tires and clothing.

The use of alternative fuel has risen steadily in recent decades and already is the dominant energy source for the cement industry in some European countries. There’s no question the amount of plastic within that category has increased and will keep climbing given a worldwide explosion of plastic waste, according to 20 cement industry players interviewed for this report, including company executives, engineers and analysts. Reuters also reviewed data from cement associations, individual countries and analysts that confirmed this trend.

For example, Geocycle currently uses 2 million tonnes of plastic waste a year as alternative fuel at Holcim plants worldwide, according to Geocycle CEO Pieters, who said the company intends to increase this to 11 million tonnes by 2040, including through more partnerships with consumer goods companies.

Fumes and dust are seen at Indonesian cement manufacturer PT Solusi Bangun Indonesia Tbk (SBI) in Bogor, West Java province, Indonesia, Sept. 21, 2021.

Pieters said the cement industry has the capacity to burn all the plastic waste the world currently produces. The United Nations Environment Program estimates that figure to be 300 million tonnes annually. That dwarfs the world’s plastic recycling capacity, estimated to be 46 million tonnes a year, according to a 2018 estimate by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), a global policy forum.

Plastic pollution, meanwhile, is bedeviling communities whose landfills are reaching capacity and despoiling the Earth’s wild places. Plastic garbage flowing into the oceans is due to triple to 29 million tonnes a year by 2040, according to a study published last year by the Pew Charitable Trusts. This detritus is endangering wildlife and contaminating the seafood humans consume.

“The cement industry is definitely a solution,” Geocycle’s Pieters said.

Toxic emissions

Consumer goods giants are turning to cement firms for help in reducing plastic litter as other initiatives stumble. Reuters reported in July that a set of new “advanced” plastic recycling technologies promoted by big brands and the plastic industry had suffered major setbacks across the world.

Cement-making is one of the world’s most energy-intensive businesses. Fuel – mainly coal – is its single-biggest expense, industry executives said. In the 1970s, producers looking to reduce costs began stoking kilns with rubbish such as tires, biomass, sewage sludge – and plastic. Those materials aren’t as efficient as coal, but are virtually free. Some local governments even pay cement makers to take this waste.

In Europe, refuse now makes up roughly half the fuel used by the cement industry. In Germany, the bloc’s biggest producer, the ratio is 70%, according to 2019 data from the Global Cement & Concrete Association (GCCA), a London-based trade organization. The United States uses 15% alternative fuel in its kilns, according to the Portland Cement Association, a U.S. industry group. Spokesperson Mike Zande said its members have the capacity to catch up with Europe.

While cost-cutting remains the primary driver, the industry in recent years has begun touting its garbage fuel as a way to reduce the “societal problem” of plastic waste, said Ian Riley, CEO of the London-based World Cement Association (WCA), which represents producers in developing countries.

So it was logical that cement makers would team up with consumer goods companies, the largest source of single-use plastic packaging, in the recent partnerships to burn discarded plastic in their kilns.

In emerging markets, big brands sell a slew of food and hygiene products packaged in plastic sachets, typically single-serving portions tailored to the budgets of poor households. Billions of these flexible pouches are sold each year. Sachets are nearly impossible to recycle because they’re made of layers of different materials laminated together, usually plastic and aluminum, that are difficult to separate.

Indonesia, an archipelago of more than 270 million people, is the second-largest contributor to ocean plastic pollution behind China, partly due to its widespread use of sachets, according to a 2015 study published in the journal Science. Plastic garbage can be seen everywhere around Jakarta, the sprawling capital of more than 10 million people. It clogs storm drains, litters its teaming slums and mars its shoreline.

Developing countries have generally welcomed assistance with waste management. Thus Indonesia was a natural location for Unilever’s waste-fuel venture with cement maker SBI and the local Jakarta government. At last year’s launch, Andono Warih, head of Jakarta’s environment service, praised the initiative and expressed hope that it would spark other such collaborations.

The project uses plastic that’s already been buried in the region’s Bantar Gebang landfill, one of the largest dumps in Asia. Waste excavated by earth-moving equipment is transported to a warehouse at the landfill site. There, it is shredded, sieved and dried into a brown mix resembling manure. That material, known as Refuse Derived Fuel (RDF), is then fed into the kiln at an SBI cement plant in Narogong, just outside Jakarta.

SBI currently uses 20% RDF at that plant, a figure that could increase to 35%, according to Ita Sadono, SBI’s business development manager. The operation still relies primarily on coal, she said, but she contends RDF is “significantly helping to reduce plastic waste.”

Unilever is helping to fund a second RDF project in Cilacap, an industrial region in Central Java, according to SBI and a 2020 sustainability report by Unilever’s local Indonesian unit. The two facilities could send 30,000 tonnes of plastic waste per year to SBI’s cement plants, according to a Reuters analysis of data provided by SBI.

Unilever did not respond to detailed questions about these projects. Sadono said in a text message that Reuters’ calculations were “OK,” without giving further details.

About two kilometers from SBI’s cement plant near Jakarta, Dadan bin Anton, 63, runs a roadside stall selling plastic sachets of soap, washing powder and instant coffee, including brands owned by Unilever. He said he often has trouble breathing and blames the cement plant.

“People here are breathing dust every day,” he said.

SBI has invested in mitigation measures to cut dust at its plants, Sadono said. And it isn’t clear whether the cement facility has anything to do with Dadan’s burning chest. Jakarta boasts some of the dirtiest air in Asia. Pollutants from industry smokestacks, agricultural fires and auto exhaust routinely blanket the city.

But some scientists say incinerated plastic is a dangerous new ingredient to add to the mix, particularly in developing nations where air-quality rules often are weak and enforcement spotty.

Heavy vehicles are seen at the Bantar Gebang landfill in Bekasi, West Java province, Indonesia, Aug. 12, 2021.

Plastic releases harmful substances like dioxins and furans when burned, said Paul Connett, a retired professor of environmental chemistry and toxicology at St. Lawrence University in Canton, New York, who has studied the poisonous byproducts of burning waste. If enough of those pollutants escape from a cement kiln, they can be hazardous for humans and animals in the surrounding area, Connett said.

Such fears are overblown, said Claude Lorea, cement director at GCCA, the industry group representing big cement firms including Holcim and Cemex. She said super-heated kilns destroy all toxins resulting from burning any alternative fuel, including plastic and hazardous waste.

But things can go wrong.

In 2014, a cement plant in Austria released hexachlorobenzene (HCB), a highly toxic substance and suspected human carcinogen, after the facility burned industrial waste contaminated with the pollutant. Cheese and milk sourced from cattle raised near that plant in southern Carinthia state were tainted, Austria’s health and food safety agency found. And blood samples drawn from area residents also contained HCB, which can damage the nervous system, liver and thyroid.

An investigation commissioned by the state government found multiple failures by local regulators and the cement plant, including that the kiln was not running hot enough to destroy contaminants like HCB.

The Austrian cement maker which operates the plant, w&p Zement GmbH, told Reuters that it had worked to eliminate all the environmental pollution from the incident and that it had provided help to the community such as replacing contaminated animal feed.

Carinthia province spokesperson Gerd Kurath said in an email that the government’s continued monitoring of air, soil and water samples in the area shows that contamination levels have declined.

The cement industry, meanwhile, is heralding waste-to-fuel as a way to fight global warming. That’s because burning refuse, including plastic, emits fewer greenhouse gases than coal, the GCCA trade group said.

Burning garbage “reduces our fossil fuel reliance,” spokesperson Lorea said. “It’s climate neutral.”

The European Commission, which sets emission rules in Europe, told Reuters that plastic does emit fewer carbon dioxide emissions than coal but more than natural gas, another fuel used by the cement industry.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, which regulates environmental policy in the world’s largest economy, reached a different conclusion. It said in a statement there is no significant climate benefit to be gained from substituting plastic for coal, and that burning this waste in cement kilns can create harmful air pollution that must be monitored.

Measuring plastic’s CO2 emissions against those of coal, the world’s dirtiest fossil fuel, is not the benchmark to use if the cement industry is serious about fighting global warming, said Lee Bell, advisor to the International Pollutants Elimination Network, a global coalition working to eliminate toxic pollutants. Reducing the industry’s massive carbon emissions, he said, requires a switch to fuels such as green hydrogen, a more expensive but low-polluting fuel produced from water and renewable energy.

“The cement industry should leap-frog the whole burning-waste paradigm and move to clean fuel,” Bell said.

The GCCA told Reuters the industry is improving energy efficiency and is considering the use of green hydrogen.

Ever more plastic

While cement plants in industrialized countries are gearing up to burn more plastic, explosive growth is anticipated in the developing world.

China and India together account for 60% of the world’s cement production in facilities whose primary fuel is coal. Over the next decade, these countries have set targets of using alternative fuel to stoke 20% to 30% of their output. If they reached just a 10% threshold, that would equate to burning 63 million tonnes of plastic annually, up from 6 million tonnes now, according to SINTEF, a Norwegian scientific research group. That’s more plastic waste than the United States generates each year.

In 2019, 170 countries agreed to “significantly reduce” their use of plastic by 2030 as part of a United Nations resolution. But that measure is non-binding, and a proposed ban on single-use plastic by 2025 was opposed by several member states, including the United States.

Thus the waste-to-fuel option may well become an unstoppable juggernaut, said Matthias Mersmann, chief technology officer at KHD Humboldt Wedag International AG, a German engineering firm that supplies equipment to cement plants worldwide. Plastic waste is quickly outstripping countries’ capacity to bury or recycle it. Burning it eliminates large amounts of this material quickly, with little special handling or new facilities required. There are an estimated 3,000 or more cement plants worldwide. All are hungry for fuel.

“There’s only one thing that can hold up and break this trend, and that would be a very strong cut in the production of plastics,” Mersmann said. “Otherwise, there is nothing that can stop this.”

That momentum has some environmentalists worried, including Sander Defruyt, who heads a plastics initiative at the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, a United Kingdom-based nonprofit focused on sustainability. The foundation in 2018 worked out waste-reduction and recycling targets with Coca-Cola, Nestle, Unilever, Colgate-Palmolive and hundreds of other consumer brands.

Defruyt said the foundation does not support its partner companies’ pivot towards incineration. Burning plastic for cement fuel, he said, is a “quick fix” that risks giving consumer goods companies the green light to continue cranking out single-use plastic and could reduce the urgency to redesign packaging.

“If you can dump everything in a cement kiln, then why would you still care about the problem?” Defruyt said.

Coca-Cola, Nestle, Unilever and Colgate-Palmolive said their cement partnerships are just one of several strategies they’re pursuing to address the waste crisis.

‘Plastic prayers’

In the central England village of Cauldon, residents have complained in recent years to the local council and Britain’s environmental regulator about noise, dust and smoke coming from a nearby cement plant owned by Holcim. Those efforts have failed to derail the expansion of that facility to burn more plastic.

When completed next year, alternative fuel, including “non-recyclable” plastics such as potato chip bags, will account for up to 85% of the facility’s fuel, according to planning documents filed with local authorities on behalf of Geocycle, which will manage the project.

The move will recover energy from plastic waste otherwise destined for landfills, the documents said.

Cauldon resident Lucy Ford, 42, said the cement maker’s plans have only added to some villagers’ fears about emissions. “They say they are the answer to all of our plastic prayers,” she said. “I don’t like the idea of it.”

Geocycle’s Pieters said he understood the community’s concerns. He said the company complies with all local regulations and that it carefully monitors the plant’s emissions, which would be lowered by the upgrades.

Britain’s Environment Agency said in an email that it took all complaints about the plant seriously. It said the Cauldon facility has a permit to burn waste and that the plant has to comply with its regulations.

Back in Indonesia, Unilever and SBI told Reuters that using plastic for energy was preferable to leaving it in a landfill.

Local environmentalists say they are alarmed that cement kilns could be shaping up as the fix for a nation flooded with plastic waste.

It would allow consumer brands to continue business as usual, while adding to Indonesia’s air-quality woes, said Yobel Novian Putra, an advocate with the Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives, a coalition of groups working to eliminate waste.

“It’s like moving the landfill from the ground to the sky,” Putra said.