Article body copy

Crab traps work a bit like Roach Motels: crabs crawl in, but they don’t crawl out. That’s good news for crab fishers’ chances of pulling in a good catch, but when traps get lost at sea, they become a menace to all sorts of animals.

With no one there to retrieve them, the traps continue to fish, says Ryan Bradley, head of the Mississippi Commercial Fisheries United, a nonprofit fishermen’s organization. “Marine life gets into the trap. Eventually, they can’t eat so they die, and then other marine life becomes attracted to it. They get into the trap, and they die. It just becomes this awful cycle of death.”

Derelict crab traps harm wildlife and disrupt other fishers, especially shrimpers. Bulky crab traps get caught in shrimping nets, tearing them open or blocking them from catching shrimp. Frustrated shrimpers, with nowhere to put the smelly traps, generally just throw them back, continuing the cycle.

But a group in Mississippi has found a solution: paying shrimpers a US $5 bounty to collect and recycle derelict crab traps. In just three years, the program has removed almost 3,000 crab traps from Mississippi waters. Crab traps are tagged, and those that are still in good condition are returned to their owners, while traps that are too broken down are recycled.

It’s a real win-win. Wildlife is safer, the water is cleaner and, says Bradley, who cofounded the program, there’s been a clear trend that shrimpers are encountering fewer traps.

The group, which includes the fishers’ association, Mississippi State University, the Mississippi-Alabama Sea Grant Consortium, and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Marine Debris Program, recently published a paper expanding on the project’s accomplishments.

Alyssa Rodolfich, a graduate student with Mississippi State University, knows the central-northern Gulf of Mexico well. She grew up in the area fishing with her dad, a charter boat captain. But she hadn’t thought much about derelict crab traps until she started working with the incentive program as an intern.

“I didn’t realize how big of a problem it was until I was on the cleaning-up end of it, after a few months of removing, like, 200 crab traps at a time,” she says. “It was heavy and gross, and the amount of by-catch in the traps was a lot.”

At the same time, she was talking with shrimpers, learning about the problems derelict traps pose for them. Now working as the program’s manager, Rodolfich says it’s gratifying to see the results. “It feels like a big accomplishment, not just to see the amount of debris that’s been removed but also to see the change in attitude and behavior,” she says.

The incentive works like a bottle-redemption program. Participating shrimpers register for the program, document the traps they collect, and tag them before turning them in to a redemption site and documenting the drop-off to claim the reward.

“It’s not uncommon for our guys to turn in five, 10, 15 of these traps from one multiday shrimping trip,” Bradley says.

Chloé Dubois, the cofounder and head of the British Columbia–based Ocean Legacy Foundation, a nonprofit focused on marine debris, calls it “a great success story.” Her organization was not involved with the project but is advocating for a similar program to be piloted in British Columbia.

Dubois says redemption programs have historically been very successful at diverting waste products at the end of their life cycle. But in the ghost fishing and marine debris sphere, she says, the Mississippi program is a pioneer. “There aren’t many examples of programs like this,” she says.

Partnering with the fishing industry on the incentives and using the program to gather data on the numbers and locations of traps while also removing marine debris further sets the program apart, she says.

Bradley says his group has fielded calls from other communities hoping to develop similar programs, though he notes that some states have legal issues that make it difficult for fishers to collect traps that aren’t their own.

In the meantime, the Mississippi program is growing and expanding. With a recent grant from NOAA, they’re starting a new pilot project—paying shrimpers to collect all the other stuff they find littering the Gulf.

“We’ve seen everything from washing machines to toilets to tires to plastic bags,” says Bradley. “The other day, one guy told me he pulled up a shopping cart. So these are the types of things we want to get out of our marine environment.”

Category Archives: News

Lobbyists kill Virginia climate change bills

Luca Powell

The proposal was simple.Wary of mounting plastic in Virginia’s bays and waterways, a state senator from Roanoke wanted to allow localities to ban plastic bags. For years, the Environmental Protection Agency has known that fewer than 10% of plastic bags get recycled and that most wind up in the ocean, slowly becoming decomposing plastic that finds its way into fish and drinking water.The senator, John Edwards, did not expect the pushback. In a committee meeting during the legislative session, five lobbyists came up to speak against the bill.One, Mike Carlin, implored the committee to give recycling a chance.“I believe that SB933 (Edwards’ bill) sends the wrong message to this industry, and is a deterrent to investment in our state, by banning plastic which can be recycled,” said Carlin, a lobbyist with the national Coalition for Consumer Choice.

People are also reading…

Similar showdowns take place several times a day during Virginia’s legislative session. Despite the developing climate crisis, bills designed to curb pollution and emissions find fierce opposition in the growing, well-financed lobbies that have put down deep roots in the commonwealth.Sometimes, the lobbyists represent companies that outwardly market themselves to customers as environmentally friendly.This session, legislators proposed a number of ideas to make Virginia more green and to make it safer from harmful chemicals.Del. Kathy Tran, D-Fairfax, proposed a bill to ban the use of coal tar sealants — the thick, black goop used to coat asphalt on driveways and parking lots.The sealants contain toxic compounds — polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, or PAHs — that leak into the environment over time and have been found in Virginia’s waterways, according to reporting from Virginia Commonwealth University’s Capital News Service.Del. Nadarius Clark, D-Portsmouth, proposed a bill to study whether Virginia’s highly active plastics industry was shedding “microplastics” into the state’s drinking water.Another bill proposed by Edwards would have required water companies to tell the public when their drinking water was found to have problematic levels of per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS, the “forever chemicals” that have been shown to harm humans and especially children.The bill was supported and presented by Chris Pomeroy, legal counsel for the Virginia Municipal Drinking Water Association.One lobbyist spoke in support. “This is just asking for a community’s right to know if their water’s safe,” said Pat Calvert with the Virginia Conservation Network.Carlin spoke against the bill, this time on behalf of the Virginia Manufacturers Association, another prominent industry lobby.He was joined by a representative from the American Chemistry Council, who said that telling Virginians when “forever chemicals” were found in their drinking water would cause “undue alarm.”The bill was tabled by the committee, which means it was killed. The votes to squelch the bill came from Dels. Michael Webert, R-Fauquier; Chris Runion, R-Rockingham; Rob Bloxom, R-Accomack; Tony Wilt, R-Rockingham; and Buddy Fowler, R-Hanover. All received A ratings from Carlin’s organization.Tran’s sealant legislation also failed, as did Clark’s bill to study plastics.Carlin did not reply to several requests for comment, nor did Brett Vassey, president of the Virginia Manufacturers Association.Unsurprisingly, money is the big differentiator between the environmental and industrial lobbies. Most of the former are nonprofits, for which it is illegal to make political donations.Trade groups, law firms and big Virginia companies like Dominion Energy have no such restrictions. All give freely to Democrats and Republicans alike, although donation data from the Virginia Public Access Project shows that Republicans benefit far more from industry-aligned lobbying groups.For example, the Virginia Retail Federation, a lobby that represents Virginia small businesses, moved over $50,000 in campaign donations in 2022. The group gave mostly to Republicans.“They’re lobbying year-round for their priorities, which is frustrating because we in the environmental space don’t have those kinds of resources,” said Connor Kish, legislative director with the Virginia chapter of the Sierra Club.

Plastic breaking down into tiny particles that float like dust in the airA short legislative session sharpens the point. Industries can simply hire more lobbyists than environmental groups, outgunning them in a game defined by time and access.In the most recent legislative session, 1,030 lobbyists had registered with the state’s ethics board. The number ticks higher every year.

Virginia Public Access Project

Meanwhile, lobbyists are also writing their own legislation to beat back bans from environmentalists.In 2022, Washington Gas pushed a bill that would ban Virginia localities from zoning buildings without natural gas hookups. Natural gas primarily is composed of methane, which accounts for about 12% of all greenhouse gas emissions.The bill came through Terry Kilgore, a Republican in the House of Delegates whose campaign has received $22,000 from Washington Gas across his 30-year political career. VPAP data shows the largest donation — a $6,000 check — came the year he put the bill forward.In a statement shared by his office, Kilgore said, “The impetus for filing House Bill 1257 was to preserve fuel choice and ensure a family’s gas stove cannot be taken away.”

A1 Extra! Luca Powell discusses the plastic polluting local waterways – A1 Extra is presented by 8@4 | A1 ExtraA version of Kilgore’s bill ultimately passed after it was reworked last August in a special session.“Lobbyists have a tremendous influence in this place,” said Edwards, the Roanoke senator who sponsored the plastics and PFAS bills. “The General Assembly is free to make their own decision, but they’re heavily influenced.”Edwards’ plastics bill was nixed by lobbyists from the Virginia Retail Federation. The lobby represents small and large businesses across the state, including Dominion, Home Depot and Target — companies that market their environmental responsibility to their customers.It was also opposed by the Virginia Food Industry Association, which is funded by donations from such grocers as Publix and Wegmans. Publix actively tracks the number of plastic bags it saves on its website. Wegmans committed to eliminating plastic bags in its Virginia stores last summer. Melissa Assalone, director of the Virginia Food Industry Association, did not return a request for comment on the lobby’s position against the bill.Ultimately, Edwards’ bill did not pass either, as it apparently failed to persuade key Democrats on the committee, including Lynwood Lewis, the committee chair.Lewis represents Accomack and Northampton counties on the state’s Eastern Shore. In his 18-year legislative career, he has received $10,000 in campaign donations from Troutman Pepper, another of the five lobbying firms that initially pushed against the plastics legislation. He also received $6,250 in campaign donations from the Virginia Retail Federation.Lewis voted “nay” on the bill.

Luca Powell (804) 649-6103lpowell@timesdispatch.com@luca_a_powell on Twitter

0 Comments

#lee-rev-content { margin:0 -5px; }

#lee-rev-content h3 {

font-family: inherit!important;

font-weight: 700!important;

border-left: 8px solid var(–lee-blox-link-color);

text-indent: 7px;

font-size: 24px!important;

line-height: 24px;

}

#lee-rev-content .rc-provider {

font-family: inherit!important;

}

#lee-rev-content h4 {

line-height: 24px!important;

font-family: “serif-ds”,Times,”Times New Roman”,serif!important;

margin-top: 10px!important;

}

@media (max-width: 991px) {

#lee-rev-content h3 {

font-size: 18px!important;

line-height: 18px;

}

}

Oregon State House declares war on modern plastics

PFAS or “forever chemicals” has been found in the blood of nearly every American, including newborn babies. Senate Bill 543 and Senate Bill 545 are significant steps forward in reducing plastic pollution.The Oregon state House passed two bills with bipartisan support to address the growing environmental and public health impacts of single-use plastics. Both bills now head to Gov. Tina Kotek’s desk for her signature. Senate Bill 543 will phase out polystyrene foam foodware, packing peanuts and coolers and prohibit the use of PFAS, the toxic substances nicknamed “forever chemicals” because of their longevity, in food packaging starting January 1, 2025. The legislation passed the House by a vote of 40-18.Senate Bill 545 instructs the Oregon Health Authority to update the state’s health code to make it easier for restaurants to provide reusable container options. This bill cleared the House by a vote of 38-18.On February 2, 2023 the Oregon Department of Agriculture officially adopted new rules enabling grocery stores, small co-ops and other retail establishments to offer sanitary reusable containers and refill systems.Senate Bill 545 directs the Oregon Health Authority to undergo similar rulemaking to allow Oregon restaurants, and their customers, to do the same.Although the subject may appear to not have any relation with fishermen and the fishing industry, it does: according to Tara Brock, Oceana’s Pacific counsel based in Portland, “plastics are overwhelming our oceans, killing marine life, and devastating ecosystems. The only way to head off this crisis is to start reducing the amount of plastic we create, use and throw away, and to start doing that as quickly as possible.”From the Ocean to your tableHere is one example of the “path” taken by plastics: when the Stockholm University study measured the level of chemicals found in women in the Faroe Islands, a remote location far from industrial or chemical pollution, they found unusually high concentrations of toxic industrial chemicals in their breast milk. According to a story published by The Guardian, “The chemicals were coming from the ocean or, more specifically, from the pilot whales that make up an important part of the islanders’ diet.”According to the article, “Inuit living in the Canadian Arctic have also been found to have higher POP levels in their blood than the general population of Canada, predominantly due to their diet of fish and marine mammals such as walrus and narwhal.” Senate Bill 543 and Senate Bill 545 aim to put an end to this cycle, which, in the end, is killing us. Several legislators and advocates celebrated the passage of the two bills as significant steps forward in reducing plastic pollution:“Products that have a ‘forever’ impact on our planet, like polystyrene foam, which doesn’t biodegrade, and PFAS forever chemicals that build up in our bodies and environment, should be eliminated,” said Senator Janeen Sollman (SD-15). “As we move away from these wasteful and harmful plastic products, we should make it easier for Oregon businesses to offer reusable options to help make the zero waste future we are working to build a reality. I am thrilled to see both of these bills pass today and look forward to Governor Kotek signing them into law.”Bills get bipartisan support“I am dedicated to working to preserve the health of our beautiful state, our wildlife and our people. Plastic pollution is harmful and we cannot recycle our way out of this significant problem,” said Representative Maxine Dexter (HD-33). “Today, with the passage of SB 543 and SB 545, we took critical steps toward prioritizing the health and beauty of Oregon above convenience by phasing out the availability of wasteful and toxic single-use plastics.”“Nothing we use for just a few minutes should pollute the environment for hundreds of years,” said Celeste Meiffren-Swango, Environment Oregon’s state director. “The two bills passed by the Oregon legislature today will help Oregon eliminate toxic and wasteful products, shift away from our throwaway culture and build a future where we produce less waste. Thanks to the Oregon legislature for passing these bills. We look forward to seeing them signed into law.” “It’s time to take out the single-use takeout! Senate Bill 543 and 545 aim to help Oregon improve on a one-way, throwaway food service economy. Businesses spend $24 billion a year on disposable food service items. As one of the top items we find on Oregon’s beaches and throughout the environment, millions more each year is spent cleaning this stuff up,” said Charlie Plybon, Oregon Policy Manager with Surfrider Foundation. “With SB 543 Oregon has the chance to become the 10th state in the nation to ban foam foodware, one of the most commonly found single-use plastics polluting beaches worldwide according to Ocean Conservancy data,” said Dr. Anja Brandon, Associate Director of U.S. Plastics Policy at Ocean Conservancy. “Meanwhile, SB 545 will help ensure that as Oregon moves away from toxic single-use plastics like foam we have better access to sustainable and reusable alternatives. These bills are complementary and crucial to tackling the plastic pollution crisis, and we look forward to Governor Kotek signing them into law. Let’s hope that legislatures around the country and in Washington, D.C., are paying attention.” “In recent years, our staff have knocked on tens of thousands of doors in Oregon about the need to move beyond polystyrene foam and the overwhelming response was ‘It’s about time!’,” said Charlie Fisher, state director with OSPIRG. “These bills move Oregon further towards a world where we reduce and reuse instead of use once and throwaway, and we’re happy to see them headed to the Governor’s desk.”“Not only is styrene toxic for human and environmental health, but so is PFAS in foodware,” said Jamie Pang, Environmental Health Program Director at the Oregon Environmental Council. “PFAS has been found in the blood of nearly every American, including newborn babies. Phasing out PFAS in foodware is a common sense way to eliminate a significant source of exposure to cancer-causing and endocrine disrupting chemicals that pollute our bodies and waterways.”

Living and breathing on the front line of a toxic chemical zone

Juan López had just returned home from his job supervising the cleaning of giant tanks that hold toxic chemicals produced along the Houston Ship Channel, one of the largest petrochemical complexes in the world.He was ready to sit down to dinner with his wife, Pamela López, and their four school-age children at their small house across the highway from the plants.But as the family gathered, the facilities were still burning off chemical emissions, sending clouds of leftover toxics toward their two-bedroom home, hitting them on some days with distinct and worrisome smells — and leaving Mr. López concerned about the health of their children.“I make good money where I’m at,” he said. “But I always felt like it was only me that was getting exposed, because I am working in the tanks with the chemicals. When the smell comes, all we can really do is try to keep everyone inside. Is that enough? I just don’t know.”He has reason to worry. Two recent assessments, by the Environmental Protection Agency and city officials in Houston, found that residents were at higher risk of developing leukemia and other cancers than people who lived farther from the chemical plants.These same worries afflict households in Illinois, Louisiana, West Virginia and other spots around the United States where families live near manufacturing facilities that make or use these cancer-causing chemicals.“Sacrifice zones — that’s what we call them,” said Ana Parras, a founder of Texas Environmental Justice Advocacy Services, which sued the E.P.A. starting in 2020 to push for tighter rules on toxics. “These areas here are paying the price for the rest of the nation, really.”The chemical plants were still burning off emissions as the López family ate dinner.Meridith Kohut for The New York TimesPamela López, 32, comforting her 9-year-old daughter, Mahliyah Angelie, who had a headache.Meridith Kohut for The New York TimesWaves of toxic chemicals drift toward the López family home at unpredictable moments, day and night.Meridith Kohut for The New York TimesAfter years of only intermittent action by the federal government and opposition from the industry, the Biden administration is racing to impose restrictions on certain toxic air releases of the sort that plague Deer Park, while also moving to ban or restrict some of the most hazardous chemicals entirely.The proposed measures would significantly cut releases of a number of cancer-causing chemicals from plants in Texas, including four of those across the highway from the López family.Companies from a variety of industries, including those that produce the substances and those that use them, are pressuring the administration to water down some of the rules, saying the repercussions of a ban or new restrictions could be economically crippling.Few communities are at greater risk than Deer Park, and few people experience the trade-offs between economic considerations and health more than Mr. López, for whom the petrochemical industry is both the source of his family income and a threat to their health.Mr. López, 33, did not graduate from high school and is proud of how much he is paid to supervise the cleaning of the chemical tanks, which his crew climbs into and scrubs from the inside, an extremely dangerous job.But he suggested that the job did not blind him to the risks the plants pose to his family, saying that “just because you help me make a paycheck does not mean you are doing everything right.”Waves of toxic chemicals drift toward the family home at unpredictable moments, day and night. Mr. López wears protective gear at work. But there are no such measures at the house, where the children ride bikes in the driveway and play with a puppy named Dharma. From the swing set in their backyard, they can see the flares from the nearby plants.

Design advice for a less toxic life

Advice on healthy candles, purging kitchen plastic and the art of dyeing fabric naturally.This article is part of our Design special section about making the environment a creative partner in the design of beautiful homes.I’ve heard some candles can create indoor air pollution and even be harmful. Are there safer alternatives?Paraffin, the wax from which many candles are made, is derived from petroleum. When it burns, it emits toxic fumes. These irritate some people’s eyes and can also exacerbate asthma and other respiratory conditions. Synthetic fragrances and colors can also produce irritating fumes. On top of that, some wicks contain lead (to make them firmer), which is released into the air.Alternatives include beeswax as well as waxes made from soy, coconut, rapeseed and other oils. Some vegans do not support the use of beeswax because it is an animal product, and some feel the beekeeping industry is not cruelty free. Soy wax is certainly more sustainable than petroleum, but its possible negatives include the use of pesticides. (Look for organic soy wax.) The other vegetable waxes mentioned are relatively clean.Be sure to read the fine print. I was recently lured in by a candle from a well-known brand that was “formulated with vegan-friendly ingredients” only to find it also contained paraffin. So make sure you’re getting 100 percent of whatever alternative wax you seek. Also, check to see if artificial scents or other chemicals have been added. (Choose candles scented with nothing but essential oils.) Look for wicks that are made from cotton, wood or hemp — and glass containers that can be recycled or reused.Organic Savanna candles, poured in Kenya, are handmade from organic soy wax and locally sourced ingredients. One hundred percent of profits from the sale of the candles helps create jobs for Kenyan women and fund children’s education. Les Crème candles have pure organic coconut wax and cotton wicks. Hive to Home candles incorporate locally sourced beeswax, organic coconut oil, cotton wicks and sustainable packaging. Rapeseed wax candles are harder to find, especially in the United States. But plenty of places sell the wax itself if you’re a candle maker.Klas FahlenMy kitchen feels like a toxic waste dump filled with plastic bags and storage containers, plastic wrap and more. Are there better choices?Indeed there are. Plastic containers have gotten a lot of negative press, especially those that contain Bisphenol A, or BPA, which has been discovered to be an endocrine disrupter linked to all kinds of potential health issues and is banned in many states. Now we are swimming in BPA-free plastics. Unfortunately, these can contain Bisphenol S (BPS), which is chemically similar.An alternative is glass or metal storage containers with silicone lids. (Silicone isn’t perfect because many communities don’t recycle it, but it is primarily made from a naturally derived material, silica, and lasts much longer than plastic.) Brands include Ikea, Pyrex, and Public Goods.You can also reuse screw-top glass jars. (If the original housed something aromatic like garlicky dill pickles, you’ll want to run the lid through the dishwasher first.)Plastic wrap and even some wax paper also contain materials derived from petroleum. Also, they are (generally) one-time-use products, so they keep your bowl of guacamole fresh for a day before off to the landfill they go.But there are plastic-free wraps, typically cotton fabric coated with some sort of wax, that can be used repeatedly to cover a jar or bowl, or wrap a piece of cut fruit or a wedge of cheese. They don’t last forever but they are typically compostable (or can be used as fire starters). I find they sometimes pick up odors, but a thorough wash in cool water and mild soap, followed by a thorough air dry freshens them. Bee’s Wrap has two versions — one coated in beeswax, the other in a vegan-friendly soy-coconut wax blend.Another clever product is Food Huggers, which are a set of five sizes of colorful, stretchy discs made from food-grade silicone. They are dishwasher, freezer, and microwave safe. You can use them as jar lids or slide them over the cut end of a lemon, onion, apple or other produce. The company also makes silicone “Hugger Bags” that take the place of plastic food storage bags.Klas FahlenI’m interested in trying natural fabric dyeing but am afraid it’s really complicated. Where can I find out more?Making dye from plants and animals goes back to ancient times and has been done by nearly all cultures. Today there is a community of dyers you can tap into for information, ideas and supplies.I’ve long been a fan of indigo, a plant in the bean family whose leaves — when soaked and fermented — produce a beautiful deep-blue dye. Other colors can be produced using flowers, roots, berries, fruit and vegetable peels, wood, and even insects.The Bible mentions a particular blue dye color, called tekhelet, whose exact formulation has been lost but is thought to have come from a secretion of sea snails.But you’re right. It’s often more complicated than simply boiling some flower petals and dunking in a piece of fabric — especially if you want the dye to be durable and stay uniform over time.Botanical Colors, based in Seattle, offers education and natural dyeing materials. They support farmers and organic and regenerative farming, organizing workshops locally and sometimes in other parts of the country, on topics including dyeing with mud, indigo, persimmon tannins and more. They also have a biweekly online show called Feedback Friday, which began during the pandemic. The group’s president, Kathy Hattori, and sustainability and communications director, Amy DuFault, speak with artists, writers and scholars about natural dyeing and color.Maiwa, based in Vancouver, sells a large range of materials for the natural dyer as well as downloadable instructions (“How to Dye With Indigo,” for instance), books, and fabrics. They promote “Slow Clothes,” or the contributions of hand spinners, hand weavers and natural dyers as an antidote to mass production. They also offer classes, many of them free, through their School of Textiles.Readers are invited to send questions to designadvice@nytimes.com.

LISTEN: The man who discovered the Great Pacific Garbage Patch is still trying to stop ocean pollution

Growing up in Long Beach California, Captain Charles Moore quickly developed a love for the ocean.Moore’s father was a chemist and sailor who frequently took him and his siblings out on the Pacific. Moore fondly recalls their long conversations about science while they stared out into the water.“When you get out there and jump in and just see that deep blue going on forever,” he says. “The biggest kind of surprise that you can get as a human being, in terms of knowing the planet that you occupy.”

So it was fate as much as luck that, decades later, it was Moore who discovered the largest-ever accumulation of plastic waste in the Pacific Ocean — what’s commonly known as the “Great Pacific Garbage Patch.”In 1997, Moore was on a sailing trip from Honolulu to Santa Barbara when hurricane winds blew him way off course. He started noticing objects bobbing in the water, like coming across a plastic soup.Moore started to play a game: Every 10 minutes, he’d come up to the deck to see if he could get a clear view of the ocean without any trash. Unfortunately, he never won.“So I said, you know what, this has got to be more than just Hansel and Gretel leaving a trail of crumbs just for me to follow home. This is not what it is,” Moore recalls. “This is gotta be a bigger phenomenon.”

Eric Risberg

/

Associated PressBags filled with plastics and debris from the North Pacific Gyre are unloaded from the Ocean Voyages Institute sailing cargo ship Kwai in Sausalito, Calif., Wednesday, July 27, 2022. The ship returned with plastics from the ocean after 45 days in the area more commonly known as the “Great Pacific Garbage Patch.” The plastics are to be recycled, upcycled and repurposed.

What Moore discovered was the first of five large floating plastic debris zones in our oceans. The largest one is estimated to be a 620,000 square mile circle of trash, and all of the zones are increasing in magnitude every day.Moore went on to found the Algalita Marine Research and Education organization in 1999, and he’s stayed at the forefront of what he calls the “Great Plastics Awakening,” to make people aware of this growing problem.According to marine biologist and ocean activist Danni Washington (who calls Captain Moore the O.G. of ocean advocacy), an estimated 4-12 million metric tons of plastic enter the ocean every year. That’s enough plastic to cover every foot of coastline on the planet.Despite that, Washington says, “it’s not about doom and gloom.”“It’s not just about projecting this idea that we’re screwed. We have to design the future that we hope for, where we see equitable and regenerative solutions being brought to the forefront.”On the KCUR Studios podcast Seeking A Scientist, host Dr. Kate Biberdorf (aka Kate The Chemist) spoke to Moore about his research and what it means for marine life. And Washington shared the latest innovations and efforts to fix the damage that humans are causing to our oceans.So how do garbage patches form in the ocean?The average American generates almost five pounds of trash every day. That’s 292 million tons of trash per year.And in the United States, we only recycle about 35% of that trash. The EPA estimates that we could be recycling up to 75%, but a lot of this waste still ends up in trash bins. And a lot of that waste is plastic.It takes a long time for plastics to biodegrade — anywhere from 20 years to 500, depending on the type of plastic and how much sunlight it gets.

Algalita Marine Research and Education A plastic bag floating in the ocean with fish swimming by.

Because the ocean is downstream from everything, a lot of the plastic waste that we throw out ends up there. Common plastics found in the ocean include polypropylene (from bottle caps and plastic straws), polyethylene (used to make our take-away containers and shampoo bottles), and nylon (often found in plastic toothbrushes and fishing nets).But it’s not just large plastic objects that we need to worry about. Over time, UV rays from the sun can weaken plastic, causing “photodegradation” to occur. When this happens, the plastic breaks into smaller chunks, sort of like what happens when you drop a champagne flute: the larger glass breaks down into smaller pieces.Now imagine picking up each of those tiny pieces, and shattering them again. This process repeats on end, until we end up with micro-plastics and nano-plastics in the ocean. And it’s still uncertain if these smaller pieces of plastic ever fully break down. This process is problematic for tiny marine life that can mistake the plastic for food.It’s proven especially destructive to plankton — a crucial source of food for larger marine life, as well as the source for nearly half the planet’s oxygen.All these big and small chunks of plastic come together in places called gyres, which are vortexes in the ocean caused by currents.

Algalita Marine Research and Education There are 5 major gyres in the ocean. These rotating currents are formed by a combination of global wind patterns and forces created from the Earth’s rotation.

“These circulating bodies of water act as accumulators for things that are floating on the surface,” Moore explains. “So those circulating bodies of water happen to comprise 40% of the world ocean.”Moore has a particular fondness for the North Pacific Gyre, the one responsible for the Great Pacific Garbage Patch.He’s returned to the patch several times over the last two decades, often taking crews of researchers with him, and has been shocked by the rapid increase in plastic he’s seen.It’s so bad, Moore says, that in 2021, the plastic in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch outweighed the plankton there by a factor of six to one. Every year, it is estimated that 100,000 mammals and 1 million seabirds are killed by plastic in our oceans. Dolphins get tangled in nets and can’t come up to the surface to breathe. Albatross eat plastic bottle caps, while whales and sea turtles consume disposable packaging and plastic bags.To truly understand the severity of the situation, Moore wants people to experience these garbage patches firsthand.“It can be so calm out there that you can just take a piece of plywood and four inner tubes and pitch a tent on it and just hang out there,” Moore says. “I think adventure tourism has a place out in the garbage patch to really see how this thing is. But part of that is the trip to get there and learning how big the ocean is and how we’ve been able to pollute something that big.” How is pollution changing marine life?Twenty years after Moore’s initial discovery of the garbage patch, he stumbled upon something much worse: a trash island.In the documentary “Sailing the Ocean of Trash with Captain Moore,” there’s footage of Moore walking on Hi-Zex Island, a floating trash mound within the North Pacific Gyre made of bound-up rope, buoys, and an accumulation of garbage.

Algalita Marine Research and Education A collection of sea debris found on an expedition in the western pacific in 2012.

“I felt like Captain Cook mapping a new island, you know, out in the middle of the ocean,” Moore says.One of the odd things that scientists have found is that, while the garbage has proved destructive to ocean environments, some species have found ways to thrive within this plastic world.Below the surface, Moore’s crews observed a tremendous amount of fish — pelagics like mahi mahi, dolphins and rudderfish, all feeding on other species that had gathered.Just recently, the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center documented 484 different species hanging out on the marine debris, the majority of which are usually found on the coast.“It’s not entirely clear 100%, but I will tell you that a big player in the potential success of a species to adapt to environmental changes is how diverse is their genome in their population,” says Alejandro Sánchez Alvarado, executive director for the Stowers Institute for Medical Research. (Disclosure: the Stowers Institute financially supports KCUR’s podcast Seeking A Scientist.)Sánchez Alvarado says that genome diversity is a lot like the makeup of your hand in a game of cards. If you have all aces, and you’re playing a game where aces can’t be played, then you’re out of luck (i.e. the species becomes extinct). But if you have a range of cards, your chances of being able to make a move are way better – these species survive.Sánchez Alvarado says this genetic diversity helps species adapt more willingly to new situations. The ones who don’t, likely die off and disappear forever.One example of a species that seems well suited for environments polluted by humans are killifish — which are sort of like the celebrity fish of toxic waters.

Algalita Marine Research and EducationMoore says surface filter feeders like barnacles, muscles and oysters tend to thrive on garbage, while creatures like salps and larvaceans struggle.

There are over 1,200 different types of killifish, and different variations have found novel ways to adapt to their specific environments. The Atlantic killifish on the eastern coast of the United States has been exposed to bad industrial pollution, but seem to be thriving nonetheless.Meanwhile, killifish have been found living in a sulfur-rich spring in Mexico, despite extremely low concentrations of oxygen. Another killifish group was sent to space and learned how to swim under weightless conditions. And when their sibling eggs hatched, they too could swim without gravity.For comparison, when goldfish were sent to space, they started to swim in a looping pattern and appeared to be miserable.“That’s what genetic diversity is all about,” says Sánchez Alvarado. “It’s exciting to see, you know, how species are adapting… But at the same time, I know that comes at a cost and that there are gonna be some things that we don’t understand might disappear before we understand them. And therefore, there may be a sense of loss, at the end of the day.”So what can be done?What’s clear is that the worsening pollution in the ocean will end up with winners and losers — which will have lasting consequences far beyond the water. Danni Washington says that to tackle this growing problem, plastic consumers, producers, and scientists all need to step up.“It’s just a matter of collective vision. It’s about innovation, it’s about creativity,” Washington says. “Bringing all these different ideas and minds and backgrounds and experiences to the table so that we can come up with the best solution possible.”“We have a lot of work to get there,” she adds.

Algalita Marine Research and Education Moore has been collecting samples from the Garbage Patch, studying the micro and nano-plastics in the water.

At this point, a complete ocean clean-up of all the micro-plastics and nano-plastics would be nearly impossible.“If you tried to clean up less than 1% of the North Pacific Ocean, it would take 67 ships one year to clean up that portion,” says Diana Parker, who works on the National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Marine Debris Program.“And the bottom line is that until we prevent debris from entering the ocean at the source, it’s just going to keep congregating in these areas. We could go out and clean it all up and then still have the same problem on our hands as long as there’s debris entering the ocean,” she says.But Washington says there are still a lot of things we can do to mitigate the situation.“When it comes to plastic pollution entering the ocean, 80% of it is coming from land-based sources,” says Washington. “So that means that we have an opportunity to intercept those pieces of plastic before they enter the water.”On top of local and individual efforts, a few non-profit organizations are stepping onto the scene. The Ocean Cleanup has gained some notoriety on social media by building high tech “interceptors,” which are positioned at the mouths of polluted rivers and harbors and funnel floating trash onto a conveyor belt.The Ocean Cleanup reports that 80% of the plastic that enters the ocean comes from 1% of the rivers on Earth. As of today, their interceptors have removed about 5 million pounds of trash from waterways.Another, more adorable solution is Mr. Trash Wheel, which is especially effective after big storms. With 5-foot googly eyes and powered by hydro- and solar energy, the semi-autonomous interceptor hangs out in harbors and collects trash — it can gobble up to 38,000 pounds in a day.

Waterfront Partnership of Baltimore

/

Associated Press Mr. Trash Wheel®, created by Clearwater Mills, has become famous in recent years for all but eliminating floating debris in the Baltimore Harbor.

Washington’s favorite is The Great Bubble Barrier, which was designed by a Dutch startup company. It uses air to create a bubble curtain that prevents plastic from moving beyond a point, pushing trash (but not marine life) into a catchment system.Outside of the ocean, there are exciting innovations coming from scientists who are working to make plastics that are more biodegradable.Like research out of the University of Sydney, which recently discovered two fungi that can break down a type of plastic in about four and a half months. There’s also been some success with a corn-bioplastic that can break down in two-three months.Another promising result involves using an invasive brown seaweed to create a biodegradable replacement for plastic wrap.But Washington also knows that to protect the ocean, humans need to keep plastic out of the water in the first place.To that end, Washington is working towards a “Universal Declaration of Ocean Rights” that is being presented to the United Nations General Assembly in September.“I think it’s so important that no matter what walk of life you’re on, no matter what you do, you can get involved,” she says. “The ocean is our life source and it requires everyone to contribute.”Where can I hear even more about this topic?Listen and subscribe to Seeking A Scientist with Kate The Chemist, from KCUR Studios, available wherever you listen to podcasts.

Seeking A Scientist is a production of KCUR Studios, made possible with support from the Stowers Institute for Medical Research and design help from PRX.This episode was produced by Dr. Kate Biberdorf, Suzanne Hogan and Byron Love, edited by Mackenzie Martin and Gabe Rosenberg, with help from Genevieve Des Marteau.Our original theme music is by The Coma Calling. Additional music from Blue Dot Sessions.

Why is chemical recycling controversial?

Gas giant ExxonMobil has launched a large-scale chemical recycling plant in Texas with the goal of recycling over 80 million pounds of plastic waste per year. However, chemical recycling has long been controversial — oil companies may be avid proponents, but environmental groups accuse them of “trying to put a pretty bow” on plastic pollution, The Guardian writes.How does chemical recycling work?Plastic waste is a steadily growing problem and a major contributor to a number of ecological problems. Currently, only approximately ten percent of plastics are recycled in the U.S. This is largely because most plastics are unable to be recycled through traditional mechanical recycling. “No flexible plastic packaging can be recycled with mechanical recycling,” explained George Huber, an engineering professor at the University of Wisconsin to Environmental Health News.In turn, some companies are trying to recycle plastic on a large scale in hopes of reducing the amount of pollution. This is known as chemical recycling which is when “plastic is heated to temperatures between 800 and 1,100 degrees Fahrenheit to break it down” and then transported to a facility to make it plastic again, writes Politico. “An advantage of advanced recycling is that it can take more of the 90 percent of plastics that aren’t recycled today … and remake them into virgin-quality new plastics approved for medical and food contact applications,” vice president of the plastics division at the American Chemistry Council (ACC) Joshua Baca told EHN.Not everybody is a fan, however, because during the process of breaking down the plastics, called pyrolysis, a number of toxic chemicals are released including benzene, mercury, and arsenic, Politico continues. Additionally, pyrolysis consumes large amounts of energy and water, leading some critics to call the process “so inefficient … it should not be called recycling at all,” per The Guardian. What do supporters say?Exxon’s recycling plant is one of the largest in the country, and the company plans on opening plants all over the world. Its goal is to have a global recycling capacity of 1 billion pounds of plastic each year by 2026. “There is substantial demand for recycled plastics,” argued President of Exxon’s Product Solutions Company Karen McKee, “and advanced recycling can play an important role by breaking down plastics that could not be recycled in traditional, mechanical methods.”Those in the industry are inclined to agree. Baca of the ACC, which is an industry group including Exxon, acknowledged “the problem of plastic in the environment,” and deemed chemical recycling as “a critical part of the solution,” to Politico. The goal is to close the loop in plastic production so new plastic no longer needs to be manufactured. Most plastic today either ends up in landfills or is incinerated, according to Chemical and Engineering News.”The beautiful thing about feedstock recycling is that you take waste plastic, you make a pyrolysis oil, and at the end of the day you make a virgin plastic,” said Carsten Larsen of oil company Dow’s plastics business. “You have a 100 percent normal grade of food-approved plastic, except instead of coming from fossil fuels, it comes from waste plastic.”What do critics say?Despite being a seemingly promising solution to plastic pollution, there are a number of downsides to this style of recycling. First, the broken-down plastic actually becomes synthetic crude oil before being turned back into plastic. Some of this oil is used for energy, thereby perpetuating fossil fuel usage, writes Politico. Also, the location of such recycling plants has brought up environmental justice concerns as they are usually built in low-income and minority communities.”They’re going to be managing toxic chemicals … and they’re going to be putting our communities at risk for either air pollution or something worse,” remarked the manager of the Center for International Environmental Law’s plastics and petrochemicals campaign Jane Patton to EHN. Plastics contain harmful chemicals like phthalates, which are known to be carcinogenic and when plastic is pyrolyzed, it produces dioxins which “can cause cancer, reproductive issues, immune system damage, and other health issues,” EHN continues.Some say Exxon’s attempt to recycle is hypocritical as the company produced six million tons of new single-use plastic in 2021, more than any other oil and gas company, according to the Plastic Waste Makers Index 2023. Phaedra Pezzullo, a professor at the University of Colorado, Boulder, commented to The Guardian that chemical recycling is “deflecting attention away from what we need, which is reducing single-use plastics and a global treaty on plastic waste.” Veena Singla of the Natural Resources Defense Council added that it is “a way for the industry to continue to expand its plastic production and assuage people’s concerns about plastic waste.”Overall, there is still no great solution to the problem of plastic pollution other than to greatly reduce its production. “We recognize the challenge with plastics is huge. So we know we need lots of different solutions here,” explained Nena Shaw, of the EPA’s resource conservation and sustainability division. “Everybody is in limbo right now, and you have all these damn industries coming in and taking advantage.”

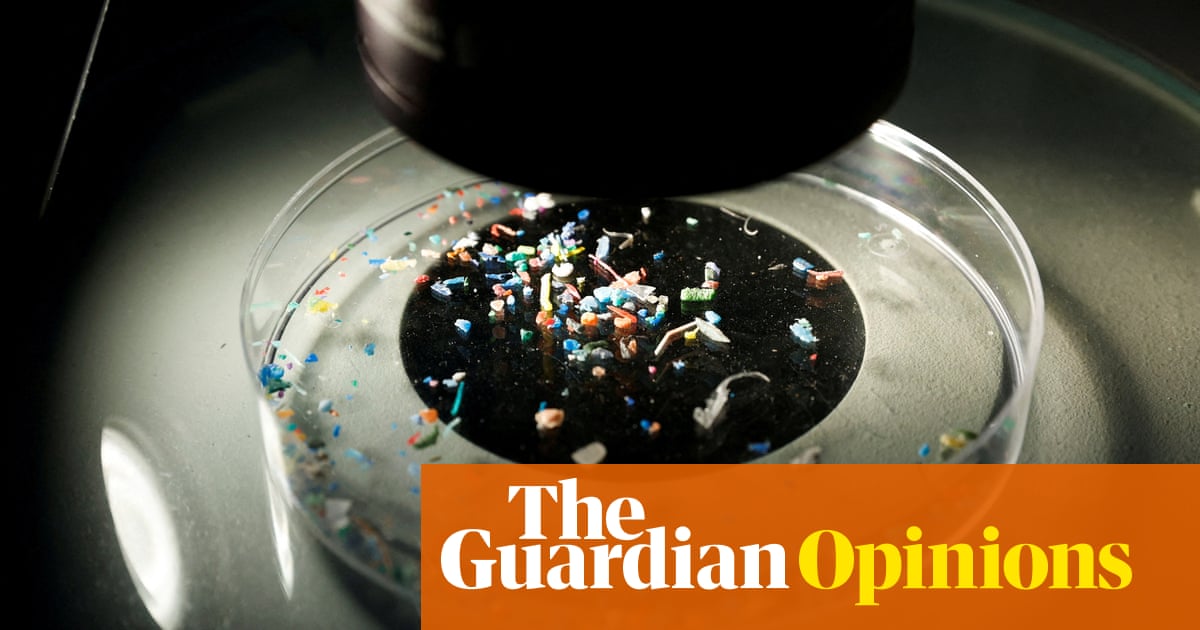

Adrienne Matei: Plastic is already in blood, breast milk, and placentas. Now it may be in our brains

Researchers at the University of Vienna have discovered particles of plastic in mice’s brains just two hours after the mice ingested drinking water containing plastic.Once in the brain, “Plastic particles could increase the risk of inflammation, neurological disorders or even neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s,” Lukas Kenner, one of the researchers, said in a statement, although more research is needed to determine the relationship between plastics and these brain disorders. In addition to potentially severe degenerative consequences, the researchers also believe that microplastic contamination in our brains can cause short-term health effects such as cognitive impairment, neurotoxicity and altered neurotransmitter levels, which can contribute to behavioral changes.In the course of their research, the team gave mice water laced with particles of polystyrene – a type of plastic that’s common in food packaging such as yoghurt cups and Styrofoam takeout containers.Using computer models to track the dispersion of the plastics, researchers found that nanoplastic particles – which are under 0.001 millimeters and invisible to the naked eye – were able to travel into the mice’s brains via a previously unknown biological “transport mechanism”. Essentially, these tiny plastics are absorbed into cholesterol molecules on the brain membrane surface. Thus stowed away in their little lipid packages, they cross the blood-brain barrier – a wall of blood vessels and tissue that functions to protect the brain from toxins and other harmful substances.While the Vienna study focused on the effects of plastics consumed in drinking water, that’s not the only way humans ingest plastic. A 2022 Chinese study concentrated on how nasally inhaled plastics affect the brain, with researchers reporting “an obvious neurotoxicity of the nanoplastics could be observed”. In basic terms, the inhaled plastics lead to reduced functioning of certain brain enzymes that also malfunction in the brains of patients with Parkinson’s disease and Alzheimer’s.Of course, we eat plastic, too, and new research on plastics and brain health is emerging alongside breaking studies on how the contaminants affect our gastrointestinal health. Much like the blood-brain barrier, the gastrointestinal barrier is also vulnerable to interference by nanoplastics – which can cause inflammatory and immune reactions in the gut, as well as cell death.At this point, it’s clear that plastics have infiltrated most parts of the human body, including our blood, organs, placentas, breast milk and gastrointestinal systems. While we don’t yet fully understand how plastics affect different parts of our bodies, many chemicals found in various types of plastic are known carcinogens and hormone-disruptors, linked to negative health outcomes including obesity, diabetes, reproductive disorders and neurological impairments in foetuses and children.This spring, the Boston College Global Observatory on Planetary Health led the first-ever analysis of the health hazards of plastics across their life cycle and found that “Current patterns of plastic production, use, and disposal are not sustainable and are responsible for significant harms to human health … as well as for deep societal injustices.”None of this is encouraging news – especially in light of the fact that plastic production is still accelerating. Yet, improving our understanding of plastic’s implications for human health is a crucial step towards banning plastic – a move 75% of people globally support. Encouragingly, more than 100 countries have a full or partial ban on single-use plastic bags, and policymakers in some countries are thinking about plastics more in terms of their costly externalities, including pollution and effects on health. Yet global plastics regulation is still vastly out of step with both scientific and public opinion.In 2021, the Canadian government formally classified plastics as toxic under the Canadian Environmental Protection Act. The move means that the government has more control over the manufacture and use of plastics, limiting the kinds of exposure that threaten health. In response, plastic producers including Imperial Oil, Dow Chemical and Nova Chemicals formed a coalition to try to crush these regulations.More countries must designate plastics as toxic and increase its regulation, doubling down on the message that when plastic affects our health – even going so far as to alter our brain function – it infringes on our human rights.

Adrienne Matei is a freelance journalist

Do you have an opinion on the issues raised in this article? If you would like to submit a response of up to 300 words by email to be considered for publication in our letters section, please click here.

Environmentalists want the FTC Green Guides to slam the door on the ‘chemical’ recycling of plastic waste

The newest flashpoint in a political battle between environmental groups and the plastics industry over “chemical” or “advanced” recycling has to do with the kinds of claims that can be made and still be truthful with American consumers.

The Federal Trade Commission is weighing its first changes in 10 years to its Green Guides, which establish guidelines for companies’ environmental advertising and labeling claims. The FTC’s review goes far beyond plastic recycling and includes concepts such as “net zero” related to greenhouse gas emissions, biodegradability, sustainability and organic products.

But recycling is front and center in the FTC review, which comes amid a global recognition of a plastic crisis, United Nations negotiations toward a treaty to curb plastic waste and the awareness of the widespread failure of plastic recycling. Tens of millions of Americans still dutifully sort their household plastic to be recycled, even though most of it ends up in landfills or is sent to incinerators.

Plastic manufacturers are also pushing hard now with media, advertising and lobbying campaigns to gain public acceptance of advanced or chemical recycling, which requires new, largely unproven kinds of chemical plants that seek to break down plastic waste with chemicals, high-heat processes, or both, and then turn the waste into feedstocks that can be mixed with fossil fuels or incorporated into new plastic products.

The industry says that through advanced recycling a “circular” plastics economy can be created that reduces the need to tap virgin fossil fuels to make its products. Environmentalists say advanced recycling is in many cases tantamount to “greenwashing”—an energy-intensive process with a high carbon footprint that essentially incinerates much of the waste and turns a small percentage into feedstocks for new plastics, or more fossil fuels.

Whichever way the FTC comes down on the question could go a long way toward reinforcing recycling policies across the country for the next decade or longer. So could the potential for new scrutiny of certain kinds of chemical recycling by the Environmental Protection Agency, announced in a draft plastic waste strategy issued late last month.

To date, the EPA has tended to view these “advanced” processes as incineration, not recycling, though the agency in its 2021 National Recycling Strategy said it would “welcome” further discussion of chemical recycling—a position it is now partially walking back.

Taken together, the FTC and EPA actions stand to affect the growth potential of the nascent advanced recycling industry across the United States. That includes one of the largest proposals—Houston-based Encina’s plan to erect a $1.1 billion chemical plant on 100 acres next to the Susquehanna River in Northumberland County, Pennsylvania, which has run into local opposition.

The plant is being designed to convert end-of-life plastics into benzene, toluene and xylene to be used to manufacture new plastic products, according to the company.

The United States has about 4.3 percent of the world’s population but generates nearly 11 percent of global plastic waste and has the biggest plastic-waste footprint of any country, generating approximately 486 pounds per person annually, according to the EPA.

A study last year by the environmental groups Beyond Plastics and The Last Beach Cleanup, found plastics recycling in the United States had fallen to below 6 percent.

Businesses cannot be trusted, said Jan Dell, founder of The Last Beach Cleanup, based in Southern California. Dell has recently put digital trackers in plastic bags or containers labeled as recyclable, dropped them off at recycling stations, then traced them to local landfills.

“There are thousands of products labeled with false recyclable labels,” she said.

A Call for Clearer Guidance or Mandates

The FTC first issued its Green Guides in 1992 and they were revised in 1996, 1998 and 2012. They provide guidance on environmental marketing claims, including how consumers are likely to interpret them and how marketers can substantiate them to avoid deceiving consumers, according to the agency.

FTC Chair Lina M. Khan

“People decide what to buy, or not to buy, for all kinds of reasons,” FTC Chair Lina M. Khan said in a Dec. 14 statement when the agency opened a comment period for the Green Guides update. “Walk down the aisle at any major store (and) you’re likely to see packages trumpeting their low carbon footprint, their energy efficiency, or their sustainability. For the average consumer, it’s impossible to verify these claims.”

More than 7,000 people, businesses and organizations submitted written comments by the FTC’s April 24 deadline, which marks the beginning of a drawn-out process that will include the agency reviewing the comments, holding workshops, drafting revisions to the Green Guides and then seeking more public comment, an agency spokesman said. The agency has posted nearly 1,000 of the comments.

Environmental, business and industry groups are all calling for clearer guidance on claims that consumers rely upon to choose what products to buy. Environmentalists want new mandates.

The Consumer Brands Association, whose members include beverage, food and drug companies and retailers including Amazon, for example, told the FTC that a comprehensive update of the guides is needed for clarity.

“The distinction between environmental benefit claims as opposed to instructions which direct consumers how to recycle products have amplified confusion in the marketplace, and consequently the potential for consumer deception,” the association wrote. “At the same time, there is a lack of clarity for (the) consumer and regulatory certainty for industry that has been exacerbated by lack of uniform federal standards, a patchwork of state approaches to environmental claims and recycling systems, as well as litigation.”

Strong reforms are necessary around recycling claims, said John Hocevar, oceans campaign director with the environmental group, Greenpeace USA.

“The FTC has an opportunity to stop the widespread greenwashing about the recyclability of plastic packaging,” he said. “It is clear that the current approach has not been successful, so it is time to codify and start enforcing the Green Guides. Once corporations stop misleading their customers that all this throwaway plastic packaging is recyclable, it will be much easier to have honest conversations about real solutions.”

Greenpeace USA joined other environmental groups including Beyond Plastics, the Center for Biological Diversity and The Last Beach Cleanup in written comments calling for FTC to give the Green Guides, which critics describe as largely voluntary, the full force of federal law while encouraging the agency to adopt California’s 2021 Senate Bill 343. The bill requires products to meet benchmarks in order to be advertised or labeled as recyclable, and is designed to help consumers to clearly identify which products are recyclable in California.

Across the country, seven categories of plastics currently include the so-called “chasing-arrows” symbol— numbered 1-7—as a sign that the material is recyclable, even though often it is not.

Of those seven, plastic bottles and jugs numbered 1 and 2 made of polyethylene terephthalate (PET) and high-density polyethylene (HDPE) are the most commonly recycled, according to a 2022 Greenpeace report that included Dell’s research. Numbers 3-7 (polyvinyl chloride, or PVC; low-density polyethylene, or LDPE; polypropylene, or PP; polystyrene, or PS; and mixtures of various plastics), are rarely, if ever, recycled, Dell said.

The environmental group Californians Against Waste described SB 343 as prohibiting “the use of the chasing-arrows symbol or any other suggestion that a material is recyclable, unless the material is actually recyclable” in most communities “and is routinely sold to manufacturers to make new products.”

The environmental groups told the FTC that it is not enough to say a plastic product is potentially recyclable. In the current plastic waste stream, only certain types of plastic bottles are actually recycled and reused again as plastic bottles. Most plastic waste, even when it contains the chasing-arrows symbol, ends up in either a landfill or an incinerator.

Environmental groups are also pressing the FTC to crack down on misleading claims of “circularity,” a new industry buzzword with no widely accepted definition that is used to suggest products are repeatedly made from waste without tapping new natural resources.

“The Guides should require that any ‘circular economy’ claim necessitates showing a decline or, at a minimum, a cap on virgin resource extraction, production, and product manufacturing and an overall reduction in emissions and toxic pollution throughout the lifecycle of the material,” according to written comments from the Center for Climate Integrity, a nonprofit that works with local communities to hold oil companies accountable for climate impacts.

Keep Environmental Journalism AliveICN provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going.Donate Now

EPA, Texas ignored warning signs at chemical storage site before it burned

Sign up for The Brief, The Texas Tribune’s daily newsletter that keeps readers up to speed on the most essential Texas news.

This story is the first of a two-part series by The Texas Tribune and Public Health Watch. Part two will publish on Thursday.

DEER PARK — Danny Hardy was sitting in the third-row pew at Deer Park First Baptist Church when the cellphones began buzzing in unison. Several men quickly shifted in their seats — all of them first responders or employees at one of the dozens of nearby refineries and chemical plants.

Hardy, a retired police officer and head of the church security team, wasn’t alarmed. After living in the Houston suburb of Deer Park for nearly 40 years, he was accustomed to the sight of refinery flares burning in the night, the occasional stench of chemicals and the sound of sirens wailing in the distance. Deer Park was nestled in the heart of North America’s petrochemical industry. These things were to be expected.

But as ripples of conversation spread through the congregation, it became clear that this emergency alert — on Sunday, March 17, 2019 — was different. After a few tense moments Wayne Riddle, a former mayor, stepped onstage and addressed the crowded worship center.

There had been an accident. A facility housing millions of barrels of volatile chemicals was burning a little more than 2 miles away. City officials had issued a shelter-in-place advisory.

Hardy looked out a window and saw a towering plume of ink-black smoke blanketing the sky. He instructed a team of 30 deacons and volunteers to shut off the air-conditioning system and guard the exits. Everyone needed to stay inside, safe from whatever fumes might be lurking outside.

The choir sang a worship song to calm the parishioners: “Lift your voice / It’s the year of jubilee / And out of Zion’s hill / Salvation comes.”

Danny Hardy inside the worship center at First Baptist Church in Deer Park on Feb. 6, 2023. As the church’s head of security, Hardy was tasked with protecting his congregation in the fire’s earliest hours. “All of a sudden, alarms on our phones started going off,” he said. “We knew it was a fire and it was pretty major.”

Credit:

Mark Felix for The Texas Tribune/Public Health Watch

* * *

Four hours later and 1,000 miles away in Boulder, Colorado, Ken Garing got an email about the mushrooming chemical fire in Southeast Texas.

For 30 years, Garing had worked as a chemical engineer for a branch of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency that investigates high-stakes cases of industrial pollution. His back stiffened when he saw that the blaze was at Intercontinental Terminals Company, or ITC, in Deer Park.

Garing had visited the 265-acre chemical storage facility twice, in 2013 and 2016. Both times, he left shaken by what he’d seen. Worrisome amounts of chemicals were leaking into the air from dozens of ITC’s massive tanks, including an outpouring of benzene, a carcinogen that can cause leukemia.

“I remember thinking, ‘Holy cow.’ They had by far the highest benzene numbers we’d ever seen inside a facility,” he said. “Something bad was going to happen at ITC. It was just a matter of time.”

A 10-month investigation by Public Health Watch found that Garing was one of many state and federal scientists who documented problems at ITC long before catastrophe struck. The fire didn’t just punctuate years of government negligence — it revealed regulatory failures familiar to communities that experience chemical disasters, including the recent train derailment in East Palestine, Ohio. The pattern is a common one: State and federal officials know for years of a looming danger but repeatedly fail to correct it. And then, after an accident occurs, they fail to adequately protect those who are harmed.

The story of how this pattern unfolded in Deer Park, a tight-knit city of 30,000 and the self-proclaimed “Birthplace of Texas,” is based on thousands of pages of state and federal documents, on investigative reports and pollution data from the EPA and on eyewitness accounts from residents. It also draws on extensive interviews with a handful of retired government regulators who tried to sound the alarm about ITC years ago and are speaking out now in the hope of preventing future disasters.

* * *

ITC’s 227 chemical storage tanks sit on the northern outskirts of Deer Park like giant, white monuments to Texas’ powerful petrochemical industry. The facility is owned by Japan-based Mitsui Group, one of the world’s largest corporations. It stores and distributes toxic chemicals, noxious gases and petroleum products essential to the region’s thousands of chemical plants and refineries, moving the products from freighters to railways, barges to pipelines, tankers to refineries. It has more than 20,000 feet of rail lines, plus five shipping docks and 10 barge docks that back up to the Houston Ship Channel. Downtown Houston is just 17 miles away.

The petrochemical industry has been intertwined with Deer Park for nearly 100 years. It is the city’s largest employer and a major philanthropic source for civic activities. It has especially close ties with Deer Park’s schools, which, along with well-paying industry jobs, are key draws for families. When the town’s school district was created in 1930, its board met at the local Shell refinery.

Barges float through the Houston Ship Channel’s murky waters next to the ITC facility in February in Deer Park.

Credit:

Mark Felix for The Texas Tribune/Public Health Watch

Deer Park has plenty of reasons to be loyal to industry. But in July 2004, Tim Doty and 14 other scientists from the state’s environmental regulatory agency — the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, or TCEQ — were focused on risks the industry might pose to the town.

The TCEQ was barely a decade old at the time, but it was already under heavy fire from environmental leaders — especially Houston Mayor Bill White, a Democrat whose city was fighting a losing battle against air pollution. The American Lung Association named Houston the nation’s fifth smoggiest city that year, and emissions from Deer Park and neighboring towns contributed to the problem. White wanted the TCEQ to toughen regulations and increase fines for repeat offenders of the federal Clean Air Act.

Doty had been tracking industrial emissions since 1990, when he went to work for the Texas Air Control Board, an agency that preceded the TCEQ. His ability to interpret complex chemical readings had made him one of its sharpest investigators. His dogged commitment made him one of its toughest.

Doty’s mobile monitoring team had taken chemical readings around ITC before.

In 2002, his scientists found startling levels of benzene and other dangerous chemicals outside the facility, including toluene, which is found in nail polish and explosives, and 1,3-butadiene, a carcinogen used in plastic and rubber products. The emissions were so strong that three of Doty’s scientists experienced burning throats, burning noses and watering eyes.

But the incident didn’t lead to any fines. The TCEQ, the state’s primary enforcer of the federal Clean Air Act, penalized ITC only once between 2002 and 2004 — for equipment problems, not chemical leaks. Most of the meager fines the company faced in that period came from the Federal Railroad Administration and the EPA.

Just six months before Doty’s team arrived in Deer Park in July 2004, ITC had illegally released 101 pounds of 1,3-butadiene into the air. But no fines were issued and 16 days later, the TCEQ gave ITC permission to install an additional tank of 1,3-butadiene. It also renewed the facility’s 10-year chemical permit — one of two key permits required of any company that emits pollution as part of its routine operation.

The TCEQ scientists spent almost a week that July combing Deer Park and surrounding communities for illegal emissions. For 13 to 14 hours each day, they triangulated emission sources along the peripheries of various facilities.

The corner of Tidal Road and Independence Parkway quickly became their top priority.

Two hazardous waste facilities and a chemical plant that produced chlorine and caustic soda, which is used in soaps and to cure foods, sat nearby. But ITC’s storage compound dominated the intersection. It was filled with tanks housing volatile fuels, including gooey leftovers from the refining process. Each tank had a number that allowed ITC — and regulators — to keep track of its emissions and compliance record over the years. The tanks in this corner, known as the “2nd 80’s” because each could hold up to 80,000 barrels of product, were 80-1 through 80-15. All of them were built in the 1970s.

That intersection “was literally ground zero for benzene,” Doty said. “There were many chemical sources around there, but ITC was right in the middle of it all. It was one of our main focuses.”

The scientists used handheld vapor analyzers to take rough measurements of chemicals in the air. They used small, metal canisters to trap air samples that would later be tested at the TCEQ laboratory. But their biggest weapons were their 16-foot box vans. The vans were outfitted with 30-foot weather masts that allowed them to track wind direction and small ovens that rapidly analyzed air samples by burning off chemicals one by one.

The scientists’ findings led to a follow-up inspection by the TCEQ. They were also summarized in an internal memo to seven agency officials, including the directors of the offices of compliance and enforcement and air permitting.

“Elevated levels of benzene and 1,3-butadiene” had been detected near the intersection of Tidal Road and Independence Parkway, the memo said. ITC, the suspected culprit, had been issued a notice of violation, a document that lists problems a company is required to address. According to the memo, ITC had released a sustained concentration of 720 parts per billion of benzene over the course of an hour, a “violation of their permit.”

But again the TCEQ let ITC off the hook.

The company said it had fixed the faulty tanks and no further action was taken. A year later, the TCEQ gave ITC permission to install 48 additional tanks.

To Doty, these decisions were just more examples of the TCEQ bending to industry rather than protecting the public.

“It was frustrating. My team was always trying to do the right thing,” he said. “Whether TCEQ actually followed up with any meaningful action, well, that’s a different issue.”

* * *

In December 2006, another problem cropped up in ITC’s “2nd 80’s.”

Emergency responders rushed to Tidal Road after a pressurized valve malfunctioned, spewing 2,076 pounds of pyrolysis gasoline, or pygas, into the air, onto the ground and into a water-filled roadside ditch.

Pygas is rich in benzene and toluene. Exposure to these chemicals can cause symptoms ranging from dizziness and irregular heartbeats to kidney damage. In extremely high concentrations they can lead to death.

Tim Doty, a former mobile air monitoring expert for the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, at his home in Driftwood, near Austin. Doty documented excessive benzene emissions near ITC’s “2nd 80’s” section for nearly a decade but watched in frustration as the chemical storage facility repeatedly escaped enforcement.

Credit:

Liz Moskowitz for The Texas Tribune/Public Health Watch

Harris County investigators closed Tidal Road for 13 hours as they managed the contaminated area and gathered air and water samples. Harris County includes Houston, Deer Park and other industrialized towns.

County officials pounced on the accident. They’d grown frustrated by the TCEQ’s leniency and were beefing up their own air monitoring and investigative efforts.

Harris County sued ITC over the pygas leak, alleging that the facility had committed six separate violations of the Texas Clean Air Act and the Texas Water Code. In their petition, the prosecutors said they were confident the case would warrant a penalty as high as $150,000 “because of the compliance history of ITC.”

Harris County updated its petition less than six months later after another ITC incident. In a span of just four minutes, nearly 1,800 pounds of 1,3-butadiene escaped from tank 50-2, the tank’s fourth emissions violation in as many years. It was located in a section of the facility adjacent to the “2nd 80’s” near Tidal Road, where Tim Doty and his team of TCEQ scientists had recorded high levels of benzene three years earlier.

Since then, Doty’s team had made four more weeklong investigative trips to Deer Park. Each time it left with new data about ITC’s troubling benzene emissions. Doty described the problems in his post-trip reports.

“I created detailed narratives and stories that anybody curious about what was happening at ITC — say, a journalist — could follow up on,” he said. “We were determined to show that ITC’s problems were consistent. They weren’t one-time events.”

Again, the TCEQ didn’t issue any penalties.

In 2008, ITC settled the lawsuit with Harris County for $95,250 for five chemical leaks caused by operator error. The company agreed to abide by environmental laws and implement better management practices — a promise it failed to keep. After another chemical accident caused by operator error the following year, Harris County sued again. This time ITC settled for $90,000.

* * *

While ITC was fending off regulators, Elvia Guevara was settling into her new home 4 miles away from its chemical tanks.

The comfortably middle-class community of Deer Park was everything she and her husband, Lalo, had hoped it would be when they moved there in 2008. The Houston suburb was small, intimate and safe. Its planned neighborhoods were lined with clean streets, large yards and spacious two-story homes. And its proximity to petrochemical facilities meant shorter commutes to work.

Elvia Guevara (left) washes dishes before her grandson’s Spiderman-themed birthday party on Feb. 11, 2023, in Pasadena, Texas. Her family moved to Deer Park in 2008. “We always wanted to live here,” she said, “because the school districts are good and it’s safe and clean.”

Credit:

Mark Felix for The Texas Tribune/Public Health Watch

Guevara managed around-the-clock logistics for a nearby chemical company. Her husband was a railroad tech manager who repaired rail lines near ITC. The industry had been good to them. It helped them move from Pasadena, a less-affluent neighboring city, and put food on the table for their three sons, Eddie, Anthony and Adrian.

“We didn’t focus on the possibility of chemical leaks and things like that,” Guevara said. “For us, it was normal to live in a community surrounded by chemical companies.”

Unbeknownst to Guevara, the EPA — the agency tasked with making sure Texas properly regulated those companies — was entering a period of turmoil. A determined regulator, Debbie Ford, had a front-row seat.

Ford arrived in Dallas in August 2008 as an air enforcement inspector for EPA Region 6, which oversees federal environmental regulations in Texas, Louisiana and three other states. She’d spent most of her life in Lake Charles, Louisiana, where her father was the medical director at a refinery. After earning a master’s degree in environmental science, she went to work for the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality, or DEQ.

Ford’s ability to interpret complicated chemical permits and memorize labyrinthine air pollution regulations shot her up the agency’s ranks. Within six years, she was the senior air technical inspector of her regional office and one of the DEQ’s most respected technical experts, especially when it came to chemical tanks.

But Ford’s rigorous approach earned her a reputation as a “pot-stirrer” in a state that, like Texas, is known for its lenient approach to enforcement. Rather than yielding to the political pressure and regulatory tiptoeing that often steered the agency, Ford pressed on — often to her bosses’ chagrin.