Plastics are responsible for wide-ranging health impacts including cancers, lung disease and birth defects, according to the first analysis of the health hazards of plastics across their entire life cycle – from extraction for manufacturing, through to dumping into landfill and oceans. Led by the Boston College Global Observatory on Planetary Health in partnership with …

Category Archives: News

How pollution is causing a male fertility crisis

Sperm quality appears to be declining around the world but is a little discussed cause of infertility. Now scientists are narrowing in on what might be behind the problem.”We can sort you out. No problem. We can help you,” the doctor told Jennifer Hannington. Then he turned to her husband, Ciaran, and said: “But there’s not much we can do for you.”

The couple, who live in Yorkshire, England, had been trying for a baby for two years. They knew it could be difficult for them to conceive as Jennifer has polycystic ovarian syndrome, a condition that can affect fertility. What they had not expected was that there were problems on Ciaran’s side, too. Tests revealed issues including a low sperm count and low motility (movement) of sperm. Worse, these issues were thought to be harder to treat than Jennifer’s – perhaps even impossible.

Hannington still remembers his reaction: “Shock. Grief. I was in complete denial. I thought the doctors had got it wrong.” He had always known he wanted to be a dad. “I felt like I’d let my wife down.”

Over the years, his mental health deteriorated. He began to spend more time alone, staying in bed and turning to alcohol for comfort. Then the panic attacks set in.

“I hit crisis point,” he says. “It was a deep, dark place.”

Male infertility contributes to approximately half of all cases of infertility and affects 7% of the male population. However, it is much less discussed than female infertility, partly due to the social and cultural taboos surrounding it. For the majority of men with fertility problems, the cause remains unexplained – and stigma means many are suffering in silence.

Research suggests the problem may be growing. Factors including pollution have been shown to affect men’s fertility, and specifically, sperm quality – with potentially huge consequences for individuals, and entire societies.

A hidden fertility crisis?

The global population has risen dramatically over the past century. Just 70 years ago – within a human lifetime – there were only 2.5 billion people on Earth. In 2022, the global population hit eight billion. However, the rate of population growth has slowed, mainly due to social and economic factors.

Birth rates worldwide are hitting record low levels. Over 50% of the world’s population live in countries with a fertility rate below two children per woman – resulting in populations that without migration will gradually contract. The reasons for this decline in birth rates include positive developments, such as women’s greater financial independence and control over their reproductive health. On the other hand, in countries with low fertility rates, many couples would like to have more children than they do, research shows, but they may hold off due to social and economic reasons, such as a lack of support for families.There is mounting evidence that pollution may be at least partly behind declining sperm quality and sperm counts (Credit: Yuichi Yamazaki/AFP/Getty Images)At the same time, there may also be a decline in a different kind of fertility, known as fecundity – meaning, a person’s physical ability to produce offspring. In particular, research suggests that the whole spectrum of reproductive problems in men is increasing, including declining sperm counts, decreasing testosterone levels, and increasing rates of erectile dysfunction and testicular cancer.

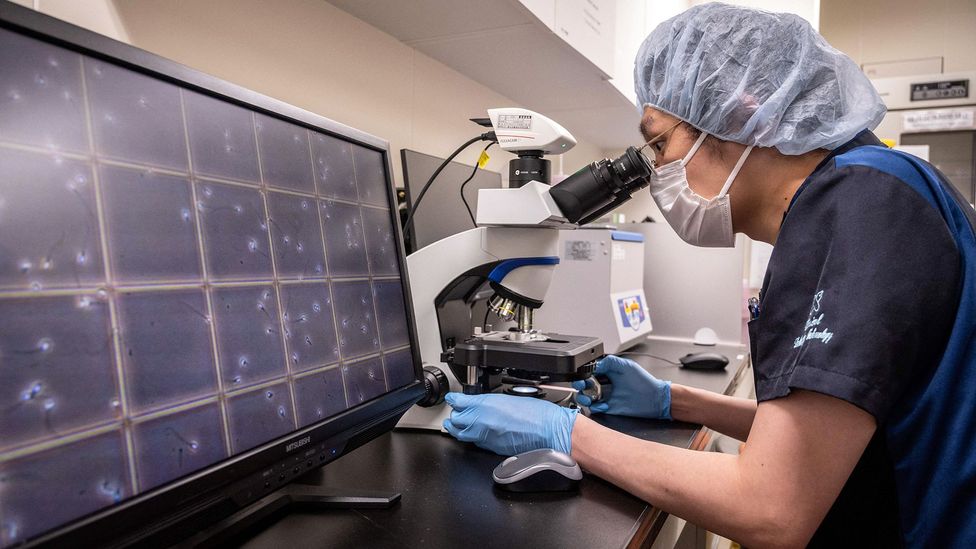

Swimming cells

“Sperm are exquisite cells,” says Sarah Martins Da Silva, a clinical reader in reproductive medicine at the University of Dundee and a practicing gynaecologist. “They are tiny, they swim, they can survive outside the body. No other cells can do that. They are extraordinarily specialised.”

Seemingly small changes can have a powerful effect on these highly specialised cells, and especially, their ability to fertilise an egg. The crucial aspects for fertility are their ability to move efficiently (motility), their shape and size (morphology), and how many there are in a given quantity of semen (known as sperm count). They are the aspects that are examined when a man goes for a fertility check.

“In general, when you get below 40 million sperm per millilitre of semen, you start to see fertility problems,” says Hagai Levine, professor of epidemiology at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Sperm count, explains Levine, is closely linked to fertility chances. While a higher sperm count does not necessarily mean a higher probability of conception, below the 40 million/ml threshold the probability of conception drops off rapidly.

In 2022, Levine and his collaborators published a review of global trends in sperm count. It showed that sperm counts fell on average by 1.2% per year between 1973 to 2018, from 104 to 49 million/ml. From the year 2000, this rate of decline accelerated to more than 2.6% per year.Levine argues this acceleration could be down to epigenetic changes, meaning, alterations to the way genes work, caused by environmental or lifestyle factors. A separate review also suggests epigenetics may play a part in changes in sperm, and male infertility.

“There are signs that it could be cumulative across generations,” he says.

The idea that epigenetic changes can be inherited across generations has not been without controversy, but there is evidence suggesting it may be possible.

“This [declining sperm count] is a marker of poor health of men, maybe even of mankind,” says Levine. “We are facing a public health crisis – and we don’t know if it’s reversible.”

Research suggests that male infertility may predict future health problems, though the exact link is not fully understood. One possibility is that certain lifestyle factors could contribute to both infertility, and other health problems.

“While the experience of wanting a child and not being able to get pregnant is extraordinarily devastating, this is a much bigger problem,” says Da Silva.

Individual lifestyle changes may not be enough to halt the decline in sperm quality. Mounting evidence suggests there is a wider, environmental threat: toxic pollutants.

A toxic world

Rebecca Blanchard, a veterinary teaching associate and researcher at the University of Nottingham, UK, is investigating the effect of environmental chemicals found within the home on male reproductive health. She is using dogs as a sentinel model – a kind of early-warning alarm system for human health.

“The dog shares our environment,” she says. “It lives in the same household and is exposed to the same chemical contaminants as us. If we look at the dog, we could see what’s going on in the human.”

Her research concentrated on chemicals found in plastics, fire retardants and common household items. Some of these chemicals have been banned, but still linger in the environment or older items (read more about this in BBC Future’s story on “forever chemicals”). Her studies have revealed that these chemicals can disrupt our hormonal systems, and harm the fertility of both dogs and men.

“We found a reduction in sperm motility in both the human and the dog,” says Blanchard. “There was also an increase in the amount of DNA fragmentation.”IVF treatment is offering hope to couples with fertility problems, but it is expensive and not available to everyone (Credit: Alamy)Sperm DNA fragmentation refers to damage or breaks in the genetic material of the sperm. This can have an impact beyond conception: as levels of DNA fragmentation increase, explains Blanchard, so do instances of early-term miscarriages.

The findings chime with other research showing the damage to fertility caused by chemicals found in plastics, household medications, in the food chain and in the air. It affects men as well as women and even babies. Black carbon, forever chemicals and phthalates have all been found to reach babies in utero.Support for men with fertility problemsAt his lowest point, Ciaran Hannington found HIMfertility, a male-only online group supporting men with fertility struggles by offering a space for them to share their thoughts and concerns. He now coaches others preparing for fertility treatment: “No one should feel like they’re on their own.”Climate change may also negatively impact male fertility, with several animal studies suggesting that sperm are especially vulnerable to the effects of increasing temperatures. Heatwaves have been shown to damage sperm in insects, and a similar impact has been observed in humans. A 2022 study found that high ambient temperature – due to global warming, or working in a hot environment – negatively affects sperm quality.

Poor diet, stress and alcohol

Alongside these environmental factors, individual problems can also harm male fertility, such as a poor diet, sedentary lifestyles, stress, and alcohol and drug use.

In recent decades there has been a shift towards people becoming parents later in life – and while women are often reminded about their biological clock, age was thought not to be an issue for male fertility. Now, that idea is changing. An advanced paternal age has been associated with lower sperm quality and reduced fertility.

There is a growing call for greater understanding of male infertility and new approaches for its prevention, diagnosis and treatment – as well as an increased awareness of the urgent need to tackle pollution. Meanwhile, is there anything an individual can do to protect or boost their sperm quality?

Exercise and a healthier diet may be a good start, since they have been linked to improved sperm quality. Blanchard recommends choosing organic food and plastic products free of BPA (Bisphenol A), a chemical associated with male and female fertility problems. “There are small things that you can do,” she says.

And, says Hannington, don’t suffer in silence.

After five years of treatment and three rounds of ICSI (Intracytoplasmic Sperm Injection), an IVF technique in which a single sperm is injected into the centre of an egg, he and his wife had two children. For people who have to pay for fertility treatments themselves, such a procedure may however not be affordable. In the US, a single round of IVF can cost upwards of $30,000 (£24,442) and insurance coverage for IVF can depend on the state you live in and who your employer is. And Hannington says he still feels the mental toll of his ordeal.

“I’m grateful for my children every day, but you just don’t forget,” he says. “It will always be part of me.”

—

Join one million Future fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter or Instagram.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “The Essential List” – a handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife, Travel and Reel delivered to your inbox every Friday.

Plastics are devastating the guts of seabirds

Northern fulmars and Cory’s shearwaters are masters of the sea and air, gliding above the waves and plunging into the water to snag fish, squid, and crustaceans. But because humans have so thoroughly corrupted the ocean with microplastics—at least 11 billion pounds of particles float at the surface, and that’s likely a huge underestimate—their diet now also includes substantial amounts of synthetic poison. A study published today in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution shows that those microplastics (defined as particles under 5 millimeters long) might be altering the seabirds’ gut microbiomes, with as-yet-unknown implications for their health. Another recent paper introduced the world to “plasticosis”: severe scarring in the digestive system of birds that had eaten plastic. With plastic pollution increasing exponentially along with plastic production, the new papers are a hint of the suffering to come.The researchers behind today’s paper dissected 85 northern fulmars and Cory’s shearwaters caught in the wild. (Northern fulmars live around northern oceans and the Arctic; Cory’s shearwaters throughout the Atlantic.) Then the team flushed plastic particles out of the birds’ digestive tracts, looking for bits as small as 1 millimeter, and analyzed the species of microbes in the gut. When the researchers analyzed microplastics in the birds by mass, the greater the mass, the lower the gut microbiome diversity. But when they counted the number of plastic particles, “the more particles there were, the more diverse the microbiome was,” says Gloria Fackelmann, a microbiome biologist at Ulm University in Germany, and lead author of the study. In this case, diversity isn’t necessarily a good thing: The more particles, the more pathogenic and antibiotic-resistant microbes the researchers found in the gut. In other words, a shift in the microbiome appears to favor potentially harmful, pathogenic microbes. Significantly, it happened among seabirds that had been eating “environmentally relevant” amounts of microplastics—meaning, what they found in their own habitat. (In previous laboratory studies, scientists have exposed various species to unrealistically high concentrations of microplastic.)This paper didn’t track whether the birds became sickened by microbial diseases, “so we can’t say the seabirds that had more plastic were unhealthier,” says Fackelmann. But that will be one of the big questions as researchers try to parse what effects the particles might be having. As microplastics break down, they leach out their component chemicals—around 10,000 varieties are used in plastics, many of which are known to be toxic to life. They’re especially prone to leach in a hot, acidic place like a digestive tract. “This all paints a really scary picture,” says Britta Baechler, associate director of ocean plastics research at the Ocean Conservancy, who wasn’t involved in either of the new papers. The gut, she says, is “a very harsh environment—things can be released, and that includes pathogens, bacteria, but also chemical contaminants.” As microplastics tumble through the ocean, they accumulate an extremely diverse community of viruses, algae, and even the tiny larvae of animals. (An especially common bacteria that scientists are finding on microplastics is Vibrio, which causes severe illness when people eat raw or undercooked seafood or are exposed to hurricane floodwaters.) This teeming world even has its own name: the plastisphere. When a fish or bird accidentally eats microplastic, it also eats that community of lifeforms. “If a seabird is ingesting more of these particles, and it does act as a vector, then you would have a higher diversity” of gut microbes, says Fackelmann.This might be why her team got contrasting results in their analysis: The more individual microplastics in the gut, the greater the microbial diversity, but the higher mass of microplastics, the lower the diversity. The more particles a bird eats, the greater the chance that those hitchhiking microbes take hold in its gut. But if the bird has just eaten a higher mass of microplastics—fewer, but heavier pieces—it may have consumed fewer microbes from the outside world.Meanwhile, particularly jagged microplastics might be scraping up the birds’ digestive systems, causing trauma that affects the microbiome. Indeed, the authors of the plasticosis paper found extensive trauma in the guts of wild flesh-footed shearwaters, birds that live along the coasts of Australia and New Zealand, that had eaten microplastics and macroplastics. (They also looked at plastic particles as small as 1 millimeter.) “When you ingest plastics, even small amounts of plastics, it alters the structure of the stomach, often very, very significantly,” says study coauthor Jennifer Lavers, a pollution ecologist at Adrift Lab, which researches the effects of plastic on sea life.Specifically, they found catastrophic damage to the birds’ tubular glands, which produce mucus to provide a protective barrier for the inside of the stomach, as well as hydrochloric acid, which digests food. Without these key secretions, Lavers says, birds “also can’t digest and absorb proteins and other nutrients that keep you healthy and fit. So you’re really prone and susceptible to exposure to other bacteria, viruses, and pathogens.”Scientists call this a “sublethal effect.” Even if the ingested pieces of plastic don’t immediately kill a bird, they can severely harm it. Lavers refers to it as the “one-two punch of plastics” because eating the material harms the birds outright, then potentially makes them more vulnerable to the pathogens they carry.A major caveat to today’s paper—and the vast majority of microplastics research—is that most scientists haven’t been analyzing the smallest of plastic particles. But researchers using special equipment have recently been able to detect and quantify nanoplastics, on the scale of millionths of a meter. These are much, much more numerous in the environment. (This is also why the finding that there are 11 billion pounds of plastic floating on the ocean’s surface was probably a major underestimate, as that team was only considering particles down to a third of a millimeter.) But the process of observing nanoplastics remains difficult and expensive, so Fackelmann’s group can’t say how many might have been in the seabirds’ digestive systems, and how they too might influence the microbiome. It’s not likely to be good news. Nanoplastics are so small that they can penetrate and harm individual cells. Experiments on fish show that if you feed them nanoplastics, the particles end up in their brains, causing damage. Other animal studies have also found that nanoplastics can pass through the gut barrier and migrate to other organs. Indeed, another paper Lavers published in January found even microplastics in the flesh-footed shearwaters’ kidneys and spleens, where they had caused significant damage. “The harm that we demonstrated in the plasticosis paper is likely conservative because we didn’t deal with particles in the nanoplastic spectrum,” says Lavers. “I personally think that’s quite terrifying because the harm in the plasticosis paper is quite overwhelming.”Now scientists are racing to figure out whether ingested plastics can endanger not only individual animals, but whole populations. “Is this harm at the individual level—all of these different sublethal effects, exposure to chemicals, exposure to microbiome changes, plasticosis—is it sufficient to drive population decline?” asks Lavers. The jury is still out on that, as scientists don’t have enough evidence to form a consensus. But Lavers believes in the precautionary principle. “A lot of the evidence that we have now is deeply concerning,” she says. “I think we need to let logic prevail and make a fairly safe, conservative assumption that plastics are currently driving population decline in some species.”

Want to help rid the ocean of plastic? Grab an oar

“We are fishing for marine plastic under sail,” says Steve Green, of Clean Ocean Sailing (COS). From their roving, rabble-rousing home and headquarters on the Annette, a 115-year-old sailing boat, Green and his co-captain, Monika Hertlová, are leading a naval attack on the plastic polluting our oceans — which weighs in at an estimated total between 75 million and 199 million tons.

Based on the coast of Cornwall in the UK, COS launched in 2017 after Green visited an island in the nearby Isles of Scilly archipelago. He was shocked at the amount of plastic pollution he saw.

“It’s only a mile across, and on the southwest of the island it is six foot deep of all sorts of plastic flotsam and jetsam. It’s full of dead or dying seabirds and dolphins,” says Green, who is “pirate-in-chief” at COS. He decided to do something about the problem and invited other concerned locals to join him in the mission to remove plastic waste from the most inaccessible parts of Cornwall’s commanding coastline. Since then, over 400 volunteers have leapt aboard to join the fixed crew of Green, Hertlová, four-year-old Simon and Labrador Rosie to sail under the Jolly Roger that flies at “Annie’s” prow.

The 60-ton former Dutch icebreaker acts as a mobile basecamp, sailing the high seas before pulling into rocky coves and river mouths so that a flotilla of smaller kayaks and rowing boats can disembark. The smaller vessels are able to reach shorelines that are difficult to access by land and that are some of the areas worst affected by plastic pollution. Plus, by using non-motorized vessels, they avoid burning carbon-emitting fossil fuels.

The group has recorded and removed 500,000 individual pieces of plastic with a combined weight of over 70 tons. Green says that about 85 percent of the rubbish they gather is recycled and repurposed. The Ocean Recovery Project in Exeter upcycles some into sea kayaks that COS then uses to remove more rubbish from nature.

COS volunteers Simon and Aude

Many Clean Ocean Sailing volunteers have a deep connection to the land and seas of Cornwall. Simon Myers grew up locally before moving away for work. During a particularly stormy winter, he returned to join the crew with his 16-year-old son Milo. For him and many of the volunteers, the work is a way to combat global issues on a local scale. “Living in western Europe we have been largely insulated from pretty much all of the consequences of our actions over the last 50 or 60 years, but we have an emotional attachment to this landscape, coastline and people. These issues around overconsumption, pollution and climate change are becoming increasingly personal. We love this part of the world. We grew up here and want to protect it,” says Myers.

Steve Green

The group is prepared to brave all weather and rough seas. They try to stay close to home when the weather demands it, but in favorable conditions they travel far up and down the coast and to the many small islands off Cornwall.

Green picks up plastic from a river bank.

Green, a native Cornishman, knows the local waterways like the back of his hand. He knows which coves, inlets, beaches and banks are susceptible to excessive plastic pollution.

Sailing ship Annette at night

Green believes COS’s method of ocean cleanup could be replicated in many of the world’s coastal areas. “There are a lot of traditional wooden boats and still a lot of people with the skills to maintain them,” he says. “I think it’s important to maintain that heritage. So long as you’re not in a hurry it is also an incredibly efficient way to move extremely heavy loads. Once the boat’s started moving, it just glides along not using any energy at all other than the natural forces of the wind and the tide.”

Ghost gear washed ashore

COS also has a “rapid response unit.” “People send us a picture or location and we have about 20 volunteers who are all set up and ready to go to pick up any ‘ghost gear’ before it gets washed out to sea again on the next tide. We have found fish crates and fishing gear from South Africa, China, South and North America. It’s crazy,” says Green.

COS volunteers clean up a beach.

A system of mutual support built on local friendships is the backbone of COS’s success. Many locals who can’t donate time offer the group goods such as beers, groceries and pasties to help keep the boat afloat and the team energized.

Rowing to hard to access spots

Annie’s “pirates” are committed to low-carbon plastic pollution cleanup. “We could go out there in big, engine-powered RIBS; we could modify tractors and all sorts to haul vast quantities of rubbish off the coast,” Green says. “But then, we would be creating another problem whilst trying to solve this one. This is nature and people working together in harmony.”

He adds, “By moving the big boat around on the sail and using oars and paddles to move the little boats around, not only are we not disturbing the wildlife but we’re not harming the natural environment at all. It takes a long time and it’s a lot of hard work, but we’re not creating a carbon footprint.”

Volunteers Simon and Milo heaving plastic

Sailing and paddling also holds an allure for volunteers, in addition to minimizing the environmental impact of COS’s work. “We are standing next to a Jolly Roger, at the mercy of the wind; it’s romantic, it’s under sail. There is a need to have quite visible, demonstrable ways to counterbalance a consumer culture,” says Myers.

The Annette flies the Jolly Roger.

“It’s also about other people seeing us doing this. Perhaps they’ll start to think about not dropping it in the first place or, even better, not buying it. That’s what’s really going to change the world,” says Green.

The Annette is a 60-ton former Dutch icebreaker.

The going can be tough for the crew, with long days of hard physical work followed by yet more days of careful sorting before sailing up the coast to the recycling center. Despite new waves of pollution washing up ashore with every fresh tide, they are determined to keep fighting back. “It’s great to see a growing amount of people with an attitude of seeing this wonderful planet as our collective home that we’re all responsible for,” says Green. As they continue to recruit new pirates for pollution-busting adventures, their message couldn’t be clearer: “All aboard.”

Why bioplastics won't solve our plastic problems

Last month, Victoria banned plastic straws, crockery and polystyrene containers, following similar bans in South Australia, Western Australia, New South Wales and the ACT. All states and territories in Australia have now banned lightweight single-use plastic bags.

You might wonder why we have to ban these products entirely. Couldn’t we just make them out of bioplastics – plastics usually made of plants? Some studies estimate we could swap up to 85% of fossil-fuel based plastics for bioplastics.

Unfortunately, bioplastics aren’t ready for prime time – except for their use in kitchen caddy bins as food waste liners. In Australia, we don’t have widely available pathways to compost or process them at the end of their lives. Nearly always, they end up in landfill.

That’s why many states are including bioplastics in their plastics bans. Avoiding single-use plastics entirely, whether traditional fossil fuel-based plastics or bioplastics, is more sustainable. And as our recycling system struggles, less plastic of any kind is simply better.

Bioplastics come from plants such as corn – and that comes with environmental impacts.

Shutterstock

Bio-based, biodegradable and compostable are different

Bioplastics is a blanket term covering plastics which are biologically-based or biodegradable (including compostable), or both.

Plastics are materials based on polymers – long-repeating chains of large molecules. These molecules don’t have to be oil-based – biologically-based plastics are made from raw materials such as corn, sugarcane, cellulose and algae.

Biodegradable plastics are those plastics able to be broken down by microorganisms into elements found in nature. Importantly, biodegradable here doesn’t specify how long or under what conditions plastic will break down.

Compostable plastics biodegrade on a known timeframe, when composted. In Australia, they can be certified for commercial or home compostable use.

These differences are important. Many of us would see the word “bioplastic” and assume what we’re buying is plant based and breaks down quickly. That’s often not true. Some biodegradable plastics are even made from fossil fuels.

Compostable bin caddies are the main sustainable use for bioplastics at present.

Shutterstock

Are bioplastics broadly more environmentally friendly?

To understand this we need to look at the whole lifecycle of the plastic, how it is made, used and what happens to it at end-of-life. Manufacturing bio-based plastics generally has lower environmental impacts and has less greenhouse gas emissions than fossil fuel plastics.

This isn’t always the case. Producing plastics from plants has an environmental impact from the use of land, water and agricultural chemicals. Increased demand for agricultural land could lead to biodiversity loss and can compete with food production.

Read more:

If plastic comes from oil and gas, which come originally from plants, why isn’t it biodegradable?

Bioplastics often sub in for familiar single use items such as plastic bags, takeaway coffee cups and cutlery. Around 90% of the bioplastics sold in Australia are certified compostable. In most of these applications a reusable alternative would be the most sustainable option.

Some applications have beneficial environmental outcomes: compostable bags for kitchen food waste caddies increase the rate of food waste collected, which means less food waste in landfill and fewer greenhouse gas emissions.

What about the crucial question of plastic waste and pollution? Sadly, if bioplastics end up in the environment, they can damage the environment in the same way as conventional plastics, such as contaminating soil and water. A turtle can choke just as easily on a bioplastic bag as a conventional plastic bag. That’s because biodegradable plastics still take years or even decades to biodegrade in nature.

Ideally, bioplastics should be designed to be either recyclable or compostable. Unfortunately, some bioplastics are neither. These pose problems for our waste management system, as they often end up contaminating recycling or compost bins when the only place for them is the tip.

In recent research for WWF Australia, we found widespread greenwashing in the industry, with terms such as “earth friendly” and “plastic-free” adding to the confusion. Regulating the industry and standardising terms would make it easier for us all to choose.

Compostable plastics almost all end up in landfill

Compostable plastics are designed to be broken down in the compost. Some can be composted at home, but others have to be done commercially.

The problem is these plastics aren’t being composted most of the time. Australian Standard compostable plastics are accepted in food organics and garden organics bins in South Australia and some councils in Hobart. But everywhere else, access to these services is limited. Many councils in other states will accept food and green waste – but specifically exclude compostable plastics (some accept council-supplied food waste caddy liners).

Read more:

Do you toss biodegradable plastic in the compost bin? Here’s why it might not break down

This means most compostable plastics used in Australia end up in landfill, where they emit methane as they break down, where it is not always captured. There’s no benefit using bioplastics if they can’t – or won’t – be recycled or composted, especially if they’re replacing a plastic that’s readily recyclable, such as the PET used in soft drink bottles.

Bioplastics still take time to degrade in landfill- and emit methane as they do so.

Shutterstock

Where does it make sense to use bioplastics in Australia?

When you reach for a bioplastic product, you’re probably doing it to reduce plastic waste. Unfortunately, we’re not there yet. We need viable pathways for recycling and composting.

So should we avoid them altogether? If you use compostable bin caddies and compost them at home or your council accepts them, that’s a useful option. But for most other uses, it’s far better to just not use plastic at all. Your reusable coffee cup and shopping bags are the best option.

Read more:

When biodegradable plastic is not biodegradable

Echo sounder buoys surprise beachcombers, anger reef guardians as more drift to Great Barrier Reef

An alarming number of strange-looking devices are washing up on Australian shores and the Great Barrier Reef, confounding beachcombers and worrying conservationists.Key points:The echo sounder buoys are used to detect fish in the South PacificQueensland commercial fishing fleets are finding them on the Great Barrier ReefConservationists are repurposing the buoys to target marine debrisThe floating echo sounders, which look like a cross between a landmine and a robot vacuum, are used by some foreign fisheries to detect and attract fish.The buoys, and the nets often attached to them, are becoming a common sight in Australian waters.This week, one of the mysterious-looking buoys washed up on a Queensland beach at Wunjunga in the Burdekin Shire south of Townsville.Reef advocates say they’re sitting on backyard stockpiles of the devices, which have been handed in.The echo sounder buoys have become a weekly discovery for commercial reef line fisherman Chris Bolton, who operates between Cairns and Townsville.”We’re finding them very regularly now, at least once a week,” Mr Bolton said.”I’m not sure how so many are getting lost.”I would say 90 per cent of the ones we find are caught on the reef.”It’s certainly a concern. It’s pollution.”Marine debris watchdog Tangaroa Blue Foundation said the buoys come from the South Pacific where fisheries, especially the long line industry, use them to detect fish.Dozens of the buoys have been donated to the not-for-profit, which is dedicated to the removal and prevention of marine debris.Lost at seaThe foundation’s chief executive Heidi Tate said some have been found as far south as New South Wales.”We do find them washing up in northern Australia every year because of the current from the South Pacific Ocean that comes towards the north,” she said.”A couple of weeks ago someone sent me a photo of one on a Sydney beach.””There are some estimates from the South Pacific fishing fleet area that somewhere between 45 to 65,000 of these beacons can be used annually.”They’ve just been lost.”

Fish sculpture aims to cut plastic pollution

South Tyneside CouncilA new seafront sculpture on Tyneside is aiming to cut the amount of plastic waste left by beachgoers.Named Feed the Fish, the artwork at Sandhaven, South Shields, is designed so people can dispose of plastic bottles which are then recycled.South Tyneside Council said it hoped it would encourage visitors to keep plastic off the beach and reduce the amount washed into the sea.The authority will work with schools and local groups to name the fish.Councillor Joan Atkinson, deputy leader of the council, said the landmark would “help to raise awareness of the risk” plastic poses to the environment.”The danger of plastic pollution to marine life and birds is well-documented.”We hope that this new sculpture will inspire and engage beach visitors to support our efforts to keep plastic off the beach and prevent it being washed into the ocean.”Every piece of plastic that is fed to the fish will make a difference to our planet through preventing pollution and supporting recycling.”It comes after the council installed 25 additional recycling bins along the seafront area last summer.Follow BBC North East & Cumbria on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram. Send your story ideas to northeastandcumbria@bbc.co.uk.Related TopicsPlasticPlastic pollutionSouth ShieldsSouth Tyneside CouncilEnvironmentRelated Internet LinksSouth Tyneside CouncilThe BBC is not responsible for the content of external sites.

City of Pittsburgh pushes back ban on single-use plastic bags

The City of Pittsburgh has delayed the rollout of its ban on single-use plastic bags. City officials said enforcement of the ban, which was previously scheduled to start in mid-April, has been pushed back until October.Pittsburgh Mayor Ed Gainey said the postponement will allow officials to better help businesses and consumers prepare for the transition.“This extra time will allow us to do the work to be able to enact this policy with proper guidance for everyone in order to make this as smooth as possible for all of us,” Gainey said in a statement Thursday.Now starting Oct. 14, the city’s ban will prohibit retailers and restaurants from distributing single-use plastic bags. Stores will be required to post visible notices about the upcoming plastic bag ban 90 days before the policy goes into effect.It’s part of a push to protect Pittsburgh’s waterways and natural lands. Single-use plastic bags sent to landfills can take 1,000 years to decompose and often leach toxic microplastics into soils and waterways.After sampling 50 of the state’s waterways, advocates with PennEnvironment found all of them contained microplastics.

Alongside the measure, the city will launch a website with public information on the ban. The Department of Public Works is slated to distribute to businesses a list of distributors for both compliant paper and reusable bags.That includes paper bags, made of at least 40% recycled material, provided to customers at a charge of at least 10 cents each. Stores that accept food assistance benefits, however, will be able to provide those bags to customers paying with WIC or EBT dollars free of cost.Enforcement of the ban will include a three-step sanctions framework by which inspectors can issue written warnings for initial violations. Those will then be followed by escalating fines.Per the legislation, the city will facilitate and support a pilot reusable bag program through which reusable bags can be purchased, donated and distributed by individuals and organizations.The City of Pittsburgh has encouraged businesses and consumers to begin going plastic-free ahead of the October deadline.Giant Eagle launched a pilot ban on single-use plastic bags at 40 of its stores. While it was cut short due to the onset of the pandemic, a company spokesperson said approximately 20 million single-use plastic bags were diverted from landfills during the two months the ban was in effect.The company said it plans to end the use of single-use plastics in all of its operations by 2025. As of October, the retailer has stopped stocking plastic bags at its stores in Columbus, Cleveland, and Erie, as well as at the Waterworks Market District in Pittsburgh.

Citing ‘racial cleansing,’ Louisiana ‘cancer alley’ residents sue over zoning

Making the case that their local government was built on a culture of white supremacy, Black residents of St. James Parish in the heart of Louisiana’s “cancer alley” have filed a federal lawsuit claiming land-use and zoning policies illegally concentrated more than a dozen polluting industrial plants where they live.

The lawsuit, filed Tuesday in U.S. District Court in New Orleans by the environmental justice groups Inclusive Louisiana and RISE St. James, and the Mt. Triumph Baptist Church, traces Black history since European settlement in the 1700s through the legacy of slavery and post-Civil War racism, to assert that parish government officials intentionally directed industry toward Black residents and away from white residents.

Outside the Hale Boggs Federal Building in New Orleans on Tuesday, leaders of the two environmental justice organizations and the church said “enough is enough” and called for a permanent moratorium on chemical plants and similar facilities along with a cleaner, safer economic future in their communities.

The plaintiffs said they have been calling for a moratorium and relief from heavy industry for several years, but to no avail.

“This is the day that the Lord has made and we shall rejoice and be glad therein because we smell victory,” said Barbara Washington, co-founder and co-director of the faith-based group Inclusive Louisiana. “Every one of us has been touched by the parish’s decisions to expose us to toxic plants. We all have stories about our own health and the health of our friends. It’s time to stop packing our neighborhoods with plants that produce toxic chemicals.”

Shamyra Lavigne with RISE St. James said: “Over and over, the St. James Parish Council has ignored us and dismissed our cries for basic human rights. We will not be ignored. We will not sacrifice our lives.”

The Center for Constitutional Rights based in New York and the New Orleans-based Tulane University Environmental Law Clinic are counsel for the plaintiffs. Chief among their claims: the parish’s land use system violates the Thirteenth Amendment as a vestige of slavery as well as the Fourteenth Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause, which bars discrimination.

“To our knowledge, this (lawsuit) is the first of its kind in the way it uses the Civil Rights statutes and Constitutional provisions to challenge this kind of pattern and practice,” said Astha Sharma Pokharel, a staff attorney at the Center for Constitutional Rights. The harms that persist today, she said, are linked to “slavery and its afterlife.”

St. James Parish officials did not immediately return requests for comment.

The Challenge of Proving Intent

Legal experts not involved in the case on Tuesday described the lawsuit as ambitious, timely and significant in its ambition and approach.

Craig Anthony (Tony) Arnold, a land-use and property rights lawyer at the University of Louisville’s Louis D. Brandeis School of Law, described the lawsuit as “strong and innovative.

“Typically, environmental justice groups have raised allegations of discriminatory local land-use practices in lawsuits against specific land-development projects or specific regulatory decisions,” said Arnold, author of the 2007 book, “Fair and Healthy Land Use: Environmental Justice and Planning,” and the forthcoming book, “Racial Justice in American Land Use.”

“When environmental justice groups have addressed systemic environmental injustices in local land-use practices, they’ve often worked with local governments to seek regulatory and policy reforms, although perhaps in the shadow of threats of lawsuits.”

What makes the St. James lawsuit distinctive, Arnold said, is that it challenges “the entire set of local land use practices and supports its arguments with a detailed history of how these land use practices have discriminated against and unequally harmed Black communities, which have ongoing impacts.”

A pipeline crosses Highway 18 in St. James Parish, Louisiana. Credit: James Bruggers

Because this pattern of racially unjust land use practices isn’t unique to St. James Parish, “perhaps we will see more such lawsuits in the future,” Arnold said.

The lawsuit illustrates a continued and welcomed emergence of the significance of environmental justice within the field of environmental law, said Patrick Parentau, an emeritus professor of law and senior fellow for climate policy at the Vermont Law and Graduate School. “This has been a long time coming,” Parentau added.

“This is the right team of lawyers to do it,” he said of the lawsuit. “It’s the right clients and the right state.”

Still, Parentau said, proving intent won’t be easy. It won’t be enough to merely map out the location of the industrial plants in Black neighborhoods, he said. “You have to get inside their heads,” he said of the parish land-use decision-makers. “You have to have minutes of meetings. Is there something in writing? Do they have recordings?”

The plaintiff’s lawyers could potentially face skeptical appellate judges and a Supreme Court with its 7-3 conservative majority, should the Louisiana case get that far. Louisiana is in the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals, which has been described as the nation’s most conservative.

Despite those obstacles, Parentau said he is “happy as hell to see this, God love them.”

Pokharel agreed proving intent can be a challenge but said the team’s lawyers have been looking closely at the history of decisions that were made, statements by people who were making the decisions and various land use practices. “We have facts throughout our complaint about how racially discriminatory these actions were, not just the consequences,” she said.

She cited as one example a decision by local officials to offer two-mile buffer zones separating industrial sites that protected certain buildings in white communities but not Black communities. The lawsuit claims that officials agreed, for example, to establish buffer zones for Catholic churches, which were majority white, and schools in white areas, but not churches or schools in Black areas.

Environmental Injustice as Vestige of Slavery

In Louisiana, parishes are like counties; St. James has five electoral districts. The 5th District is 88.6 percent Black and the 4th District is 53 percent Black, the only two that are majority Black.

The plaintiff’s group’s members live in the areas where their enslaved ancestors labored on brutal sugarcane plantations, and want access to the graves of their ancestors, which have been covered over or fenced off by industries, infringing on religious liberty, according to the lawsuit.

Keep Environmental Journalism AliveICN provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going.Donate Now

Every stage of plastic production and use is harming human health: Report

Plastic production is on track to triple by 2050, a potential influx of hazardous materials that the Earth and humans can’t handle, according to a new report from the Minderoo-Monaco Commission on Plastics and Human Health.

Experts say the report is one of the most comprehensive to date in compiling evidence of plastics’ risks for humans, the environment and the economy at every stage of their lifecycle. The commission — a group of researchers organized by the Australian foundation Minderoo, the Scientific Center of Monaco and Boston College — found plastics disproportionately harm low-income communities, people of color and children. They’re urging negotiators of the United Nations Global Plastics Treaty to take bold steps, such as capping plastic production, banning some single-use plastics and regulating the toxic chemicals added to plastics. Countries launched the plastics treaty process in March 2022, with the goal of adopting it in 2024.

From production through disposal, plastics impact people and the environment. At fossil fuel extraction sites (most plastics are made from fossil fuels like oil or natural gas) and plastic production facilities workers and surrounding communities are exposed to pollutants that can cause reproductive complications such as premature births and low birth weights, lung cancer, diabetes and asthma, among other illnesses.

Use of plastic products can expose people to toxic chemicals, including phthalates, which are linked to brain development problems in children, and BPA, which is linked to heart attacks and neurological issues. At the end of the plastics supply chain are growing landfills that leach harmful materials into the environment and surrounding communities. These landfills are often found in poor countries, described in the report as “pollution havens.”

“The bottom line is that plastic is not nearly as cheap as we thought it was, it’s just that the costs have been invisible,” Dr. Philip Landrigan, a pediatrician, director at the Boston College Global Observatory on Planetary Health and lead author of the report, told Environmental Health News (EHN). In fact, health-related costs resulting from plastic production were more than $250 billion in 2015, the report found.

He explained that the commission’s recommendations for the those discussing the treaty could prevent many of those costs to environmental health and the economy.

Plastics production caps and bans

Countries launched the plastics treaty process in March 2022, with the goal of adopting it in 2024.Credit: United Nations “There needs to be a global cap on plastic production,” Dr. Landrigan said. This cap would allow some plastic production, but prevent the anticipated growth of plastics in the coming years. Production is increasing in part because the fossil fuel industry is looking for new markets as rising demand for renewable energy could decrease the need for fuel, the report says.The commission hopes countries signing the Global Plastics Treaty will ban avoidable plastics alongside capping production. Roughly 35% to 40% of plastic goes into disposable single-use items, and that fraction is expected to increase. “We need to get in charge again of why we use plastic,” Jane Muncke, managing director and chief scientific officer at the Food Packaging Forum who was unaffiliated with the report, told EHN.

Plastic waste and health harms

Less than 10% of plastics are reused or recycled, according to the report, and the rest is burned or goes into landfills with devastating human and environmental tolls. Areas where plastic is burned experience elevated pollution and health risks. For example, plastic burning is linked to about 5.1% of lung cancers in cities in India, according to the report. Waste from electronics, with plastic and metal components, creates harmful exposures for the people around them, including roughly 18 million children working with electronic waste, the report says.For plastics that remain on the market, the commission hopes to see improved health and safety testing of the thousands of chemicals added to plastics. There are more than 2,400 chemicals added to plastics that are considered a high risk, the report says, and many others have never been tested. “The burden of proof that a chemical is problematic ends up being on society, when people start having health problems,” Andrea Gore, a professor of pharmacology and toxicology at the University of Texas at Austin, told EHN. To change this, the commission proposes testing chemicals for toxicity before they’re added to plastic products that are sold. Exposure to plastics “falls most heavily on poor people, minorities, Indigenous populations, and of course, kids,” Dr. Landrigan said. He explains that generally, poor countries facing plastic pollution want to see global commitments to reduce plastics and their health harms, while countries that produce plastics might be wary of regulations that reduce the industry’s profits.

“It’ll spin out of control”

The second negotiation meeting for the Global Plastics Treaty will start in Paris in late May. The initial meeting covered procedures and included representatives from 160 countries. It saw conflict between the High Ambition Coalition, made up of 40 countries who advocate for the treaty to include mandatory actions, and others, including the United States, who want the treaty to result in pledges from each country.For individuals concerned about plastic in their own life, Gore recommends reducing contact with plastic wherever is practical and avoiding heating plastic in the microwave, which can leach toxics. “Don’t panic, because it is easy to get very alarmed,” she said. ”This document gave me hope and has very strong recommendations.” Dr. Landrigan points out that while reducing harms from plastic can seem daunting, there are examples of policy changing the environment for the better, such as the Clean Air Act, which reduced U.S. air pollution by 77% from 1970 to 2019. But, he said, “if we don’t act courageously and just let the plastic crisis continue to escalate, it’ll spin out of control.”From Your Site ArticlesRelated Articles Around the Web