Plastic causes illness and death across its lifecycle, from production to use and disposal, a team of nearly 50 scientists concludes in a report to be made public Tuesday.

The risk can come from being near oil and gas extraction, working in plastic manufacturing plants or living near them, eating food heated in plastic packaging or breathing the air near incinerators where plastic waste gets burned as trash.

The report was produced by the Minderoo-Monoco Commission on Human Health, a body of scientists assembled by the Australian-based Minderoo Foundation, and published by Annals of Global Health, a peer-reviewed scientific journal.

The commission concluded that global plastic production, use and disposal patterns are responsible for significant harm to human health, the environment and the economy, and are causing deep societal injustices, particularly to children. It recommended establishing health-protective standards for plastic chemicals under a United Nations plastics treaty that’s being negotiated now, and a cap on plastic production, which is otherwise expected to triple by 2060.

The report is the latest by scientists who have documented the ubiquitous nature of plastic in the world, and the environmental consequences.

Plastic waste and microplastic particles have been found on the highest mountaintops and in ocean trenches; in the stomachs of whales and other marine mammals, and in our bodies, leading to mounting concerns about what all that plastic might be doing to the planet, wildlife and people.

The commission’s focus on health accentuates those concerns, especially as they relate to a debate over how plastic affects human health.

A lead author of the report, Dr. Philip J. Landrigan, a pediatrician, epidemiologist and director of Boston College’s Global Public Health Program and Global Observatory on Planetary Health, said the debate is largely resolved.

“The level of scientific certainty is absolute,” he said. “There are still details to be worked out about the exact magnitude, but there is no doubt whatsoever that plastic causes disease, disability, premature death, economic damage and damage to ecosystems at every stage of its life cycle. And the life cycle begins with the extraction of the oil, the coal, and the gas that are the building blocks for 98 to 99 percent of plastics.”

Dr. Philip Landrigan speaks at a plastics workshop at Bennington College in 2022. Credit: James Bruggers

Landigran has been studying the health effects of environmental pollutants for decades and worked on the first studies that linked the dangers of lead exposure to children.

He was also a pioneer in defining children’s unique susceptibilities to pesticides and other toxic chemicals and, while at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, was centrally involved in the medical and epidemiologic studies that followed the destruction of the World Trade Center on Sept. 11, 2001, and health impacts to thousands of rescue workers.

In recent years, Landrigan has turned his attention to plastic. The commission, he said, is an offshoot from work he did on human health and ocean pollution with the Scientific Center of Monaco, a partner in the new plastics report, along with Boston College and the Minderoo Foundation. The commission included health experts, biological oceanographers and environmental scientists who collaborated to quantify plastic’s risks to all life on earth.

Among the commission’s key findings:

Plastic causes disease, impairment and premature mortality at every stage of its life cycle, with the health repercussions disproportionately affecting vulnerable, low-income and minority communities, particularly children.

Toxic chemicals added to plastic and routinely detected in people are known to increase the risk of miscarriage, obesity, cardiovascular disease and cancers.

Plastic waste is ubiquitous and the ocean, on which people depend for oxygen, food and livelihoods, is “suffering beyond measure, with micro- and nano plastics particles contaminating the water and the sea floor and entering the marine food chain.”

“It is not ethical to deliberately expose humans to toxic chemicals,” said Sarah Dunlop, co-author and head of plastics and human health at the Minderoo Foundation, based in Nedlands, a suburb of Perth in Western Australia. “And yet, that’s what’s happening every day of our lives. These chemicals are being detected in our blood, our urine, our amniotic fluid, you name it, because the chemicals leach out of the plastic.”

Andrew and Nicola Forrest founded Minderoo Foundation in 2001. Andrew Forrest is a mining magnate and multi-billionaire. The couple has pledged to give away much of their fortune.

In February, the foundation released a report that concluded that despite rising consumer awareness, corporate attention and regulation, there is more single-use plastic waste than ever before—an additional 6 million metric tons generated in 2021 compared to 2019 and still almost entirely made from fossil fuels.

Toxic Chemicals With Our Fast Food

The report synthesizes the state of scientific knowledge on plastics and health, citing scores of research references. It includes a new calculation that health-related losses from plastics production exceeded $250 billion globally in 2015. In the United States alone, health costs of disease and disability caused by certain chemicals used to make plastic likely exceeded $920 billion in 2015, the report found.

Plastic production released nearly 2 gigatons of carbon dioxide annually, which would amount to a single-year cost of $341 billion, according to the report. In all, plastic accounts for as much as 5 percent of all greenhouse gas emissions across its lifecycle, equivalent to emissions from Russia, making it a large-scale contributor to climate change, according to the report.

The report stands in sharp contrast to how the chemical and plastics industry describes plastics in society. Rather than a scourge, the industry touts oil and gas development as a source of jobs and energy independence, plastics production as means of economic development and plastic products as a social and personal benefit of modern society.

Plastics keep food fresh and safe to eat and reduce food waste and the waste’s methane emissions, industry representatives say. They say that plastics make shipping materials, cars and trucks lighter so they use less fuel, and they note that plastics are widely used in the health care system.

The industry and trade groups also argue that they are working to end plastic pollution through so-called “advanced recycling” techniques—still largely unproven—that use heat and chemicals to turn plastic waste into fossil fuels and other feedstocks to produce new plastic products.

“We don’t have to get rid of all plastics,” Landrigan said. “I mean, I am a medical doctor. I use IV bags. I use endoscopes. A lot of plastics are essential. But why does 40 percent of current production have to be single-use plastic stuff we use and throw away?”

In an interview, Landrigan sketched out the life cycle of health risks.

One example, he said, is the recent train derailment and disaster in East Palestine, Ohio, which required burning off carcinogenic vinyl chloride from five train cars and produced a huge fire and cloud of toxic smoke. The chemical is used to make polyvinyl chloride (PVC) plastic.

Workers exposed to some of the thousands of chemicals used to make plastic are also at risk, as well as communities near manufacturing plants, he said.

“Think about the little kid chewing on the rubber ducky, and swallowing the phthalates that squeeze out of the rubber ducky,” Landrigan said, referring to chemicals used to make plastic more durable. Phthalates are endocrine disrupters that can mimic or block hormones, with potentially serious consequences, studies have shown.

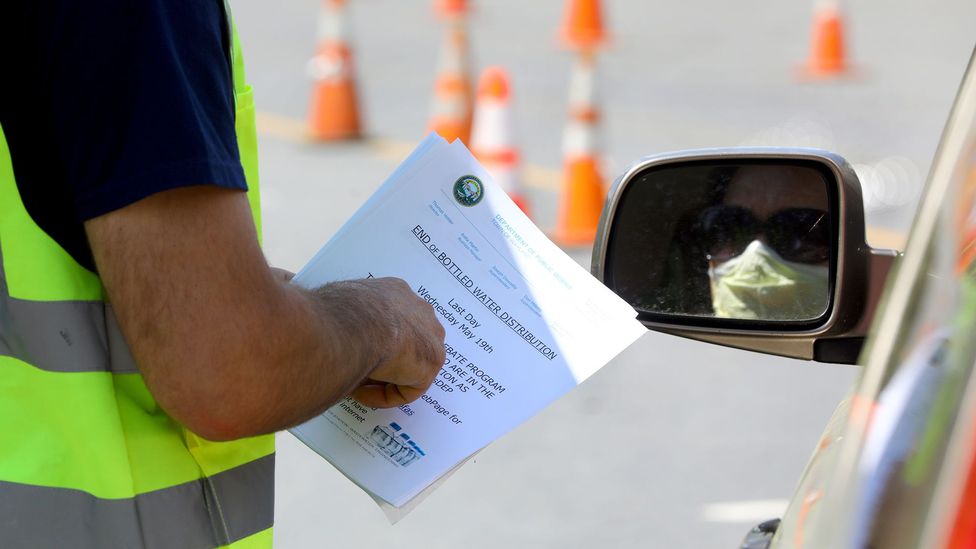

Plastic waste is often dumped in landfills or incinerated—only 9 percent of it is actually recycled and used again—and a large amount of the waste gets shipped overseas “to countries that are least equipped to deal with it,” Landrigan said.

The report cited research that found that pregnant women living in homes with PVC flooring have significantly higher urinary levels of some metabolites of phthalate than pregnant women living in homes made with other flooring materials. That signals greater phthalate exposure.

Keep Environmental Journalism AliveICN provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going.Donate Now