The backlog in the vinyl industry since the pandemic began means that artists and some music fans are having to wait around a year to receive their records.Global demand for albums is at its highest in 30 years, while most factories are still using the same pressing methods deployed in the 1980s.But a Dutch firm is offering, what it says is, a more sustainable – but more expensive – solution to the backlog.And it is doing so without the material that gave vinyl its name.Harm Theunisse, owner of Green Vinyl Records, in Eindhoven, believes it is the “new standard” for the industry.His team has spent the past seven years developing a new large-scale pressing machine that uses up to 90% less energy than typical vinyl production, and which can be monitored in real time rather than retrospectively. “This machine can do almost 40% more capacity than the traditional plants, too,” said Theunisse.”The pressing here is both faster and better for our planet.”The machine in Eindhoven avoids using PVC (polyvinyl chloride – which gave vinyl its name) – the most environmentally damaging of plastics, according to Greenpeace.Instead, it uses polyethylene terephthalate (Pet) – a more durable plastic which is easier to recycle. Theunisse said he wanted to do something to enable future generations to listen to music on vinyl without worrying about the environmental impact. “It’s for the kids,” he said. “Our world is heating up.”The barrier to finding eco-friendly alternatives to PVC has always been the desire to match the same rich sound quality while maintaining the hardness and durability of plastic, says Sharon George, senior lecturer in sustainability at Keele University.Green Vinyl Records’ method is “a real step in the right direction”, she says.”We need to stop thinking about the cost at the till and think about that cost to the planet and to our health,” she adds. Worldwide demand for vinyl is currently estimated at around 700 million records a year, as a result of a resurgence in popularity coinciding with supply chain problems during the Covid pandemic.The big factories are having to turn away business.”It’s nice to have such a full order book,” said Ton Vermeulen, chief executive of vinyl manufacturing company Record Industry, in Haarlem, near Amsterdam.But there are issues, he says, with people “always over- or under-ordering”.”When they have a new album out, they order 1,000 [copies] and, by the time they’re getting it, they already need 1,500.”Mr Vermeulen says his company is dealing with frustrated customers who have album plans and gigs booked around release dates. He is having to tell record labels and artists to wait.”They’re willing to pay more. They say ‘whatever it costs, it doesn’t matter’ – but unfortunately, it doesn’t work like that. It’s the whole chain we need to go through,” he told BBC News.PainstakingVinyl has been manufactured at Vermeulen’s factory since 1957 and the company prides itself on its heritage methods, using the same 33 presses, which are painstakingly maintained. First a master disc is made of metal and converted into a stamper. Then PVC pellets are loaded into the machine, melted and pressed into the mould.The machines stay on for 17 hours and churn out 50,000 PVC records per day. The audio here is made and packed for the three major labels: Sony, Universal and Warner Music; deals that have been in existence for decades.Vinyl manufacturer Record Industry is trying to be conscious of the planet, too – from recycling waste to investing in solar power.So what does its boss think of a more environmentally-friendly future for pressing records?”I’ve had calls saying, ‘Hey, can you press records from the plastic from the ocean?’,” said Mr Vermeulen. “We could give it a try and it might look like a record – but if it needs to sound like a normal record, there’s where we have a problem.””When you want to keep the quality of the product as it is now, then that’s impossible,” he says.The molecular attributes of the plastic are thought to have a significant impact on the quality of how the music sounds – so pressing plants want to avoid using impure materials.High costMr Vermeulen was involved with the Green Vinyl project when it began, but he raises concerns about the costs.”I think it’s the unknown aspects, and the costs involved to put high investment in – because these machines are massively more expensive than the presses we use over here,” he said.”I’m not saying there is no space for such a new technique, but I have doubts if companies are going [to go] for it.”But it seems some are willing to take the risk. Tom Odell’s new album is being pressed at Green Vinyl Records.And Harm Theunisse has just signed his first order from Warner, too. The entrepreneur acknowledges the initial costs, but estimates a return on investment in around 18 months. “You’ve got to buy one and then listen to it yourself,” he says.You can hear more about green vinyl pressing on BBC World Service podcast Tech Tent.Follow Shiona McCallum on Twitter @shionamcMore on this storyGovernment to ban single-use plastic cutlery28 August 2021Single-use plastic cutlery ban edges closer20 November 2021How vinyl records are trying to go green24 June 2021

Category Archives: News

UN seeks plan to beat plastic nurdles, the tiny scourges of the oceans

UN seeks plan to beat plastic nurdles, the tiny scourges of the oceans Billions of the pellets end up in the sea, killing turtles, whales and dolphins, and are washed up on beaches around the world Maritime authorities are considering stricter controls on the ocean transport of billions of plastic pellets known as nurdles after …

Continue reading “UN seeks plan to beat plastic nurdles, the tiny scourges of the oceans”

The petrochemical industry is convincing states to deregulate plastic incineration

The petrochemical industry has spent the past few years hard at work lobbying for state-level legislation to promote “chemical recycling,” a controversial process that critics say isn’t really recycling at all. The legislative push, spearheaded by an industry group called the American Chemistry Council, aims to reclassify chemical recycling as a manufacturing process, rather than waste disposal — a move that would subject facilities to less stringent regulations concerning pollution and hazardous waste.

The strategy appears to be working. According to a new report from the nonprofit Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives, or GAIA, 20 states have passed bills to exempt chemical recycling facilities from waste management requirements — despite significant evidence that most facilities end up incinerating the plastic they receive.

“These facilities are in actuality waste-to-toxic-oil plants, processing plastic to turn it into a subpar and polluting fuel,” the report says. Tok Oyewole, GAIA’s U.S. and Canada policy and research coordinator and the author of the report, called for federal regulation to crack down on the plastic industry’s “misinformation” and affirm chemical recycling’s status as a waste management process.

Chemical recycling is an umbrella term that refers to a handful of different processes. The most common ones, pyrolysis and gasification, start by melting discarded plastics under high heat and pressure, either in a low-oxygen atmosphere (pyrolysis) or by using air and steam (gasification). Both processes produce an oily liquid that can technically be re-refined back into plastic. However, despite decades of experimentation, the petrochemical industry has never been able to overcome economic and technological barriers to do so at scale.

Instead, the fuel produced by most chemical recycling facilities ends up being burned — either onsite or after being shipped to cement kilns and waste processors across the country. This allows companies to generate energy from the discarded plastic, but at great cost to the environment and public health: According to one recent investigation from the nonprofit Natural Resources Defense Council, a single chemical recycling facility in Oregon produces nearly half a million pounds of benzene, lead, cadmium, and other hazardous waste per year, along with hazardous air pollutants that can cause cancer and birth defects. The report also found that, of the eight chemical recycling facilities currently operating in the U.S., six are located near communities whose residents are disproportionately Black or brown. Five of these facilities are primarily “plastic-to-fuel” operations, two are turning plastic into chemical components whose end uses aren’t disclosed, and one claims to be turning carpet into nylon.

If pyrolysis and gasification can’t turn plastic back into plastic — not economically or at scale, anyway — why does the petrochemical industry want to pass legislation that calls it manufacturing?

Sorted bales of plastic.

Getty Images

Lee Bell, a policy adviser for the International Pollutants Elimination Network, a coalition of more than 600 nonprofit organizations, said there are a couple reasons. First off, it’s a great PR move. What the industry wants, he explained, “is some sort of leverage to prevent regulation, and currently that’s what chemical recycling is.” By convincing lawmakers that they’re giving new life to old plastics, petrochemical companies may be able to stave off more stringent policies to crack down on plastic production. For example, in its opposition to a major plastic-reduction bill that recently passed in California, the American Chemistry Council cited its investments in chemical recycling.

The other reason is more immediate. Waste management facilities are usually subject to tighter public health and environmental regulations than manufacturing facilities — both at the federal level and by individual states. They may be required to submit toxic air contaminant inventories to regulators, or they may be subject to more stringent pollution caps.

Chemical recyclers don’t want to have to meet these regulations, said Veena Singla, a senior scientist for the NRDC. “They’re trying to duck those requirements and go for the more lax requirements for manufacturing.”

Jed Thorp, state director for the Rhode Island chapter of Clean Water Action, an environmental nonprofit, said he’s seen this firsthand in his own state, in a recent bill that proposed exempting new chemical recycling facilities from waste management regulations. Doing so, Thorp said, would have absolved the facilities’ operators from having to hold public hearings, accept comments from community members, and disclose the plants’ projected pollution.

The Rhode Island bill, which passed the state Senate in June, was ultimately rejected by House legislators, although Thorp expects it to return next year — potentially with smarter messaging from its petrochemical industry backers. Thorp said he expects groups like the American Chemistry Council to “reinvent the whole argument and talking points on this to be able to better sell it in the future.”

In response to Grist’s request for comment, the American Chemistry Council rejected the characterization of chemical recycling as incineration and pledged to continue advocating for it to be regulated as a manufacturing process. Matthew Kastner, a spokesperson for the trade group, said that solid waste regulations are often “irrelevant” to the processes involved in chemical recycling and that plastic-to-fuel is “no longer the focus” of most facilities.

A sandpiper feeds in a marsh near a plastic water bottle.

Getty Images

According to GAIA’s report, lawmakers have proposed legislation to exempt chemical recycling from waste management regulations in at least five other states, including Michigan and New York. Other bills not tracked by GAIA may provide financial incentives to build more pyrolysis and gasification facilities or explicitly count them as “recycling” in states’ extended producer responsibility laws. (These laws require plastic makers to foot the bill for recycling the products they make.)

The news isn’t all bad, however. GAIA identifies some positive trends, including legislative efforts in Oregon and Minnesota to accurately define pyrolysis, gasification, and other “chemical recycling” processes as incineration — aka waste management. Those bills were ultimately unsuccessful, but Oyewole said they suggest policymakers are catching on to the petrochemical industry’s strategy.

“Some legislators are learning more and not letting the wool be pulled over their eyes about what these processes are,” she said.

Another potentially positive sign: The Environmental Protection Agency announced last November that it had begun to consider whether chemical recycling should be regulated under Section 129 of the Clean Air Act. This would define chemical recycling processes as “incineration” once and for all — potentially delivering a forceful blow to the petrochemical industry’s state-by-state legislative strategy, although Oyewole said it’s unclear whether the agency’s determination would override existing state legislation.

Besides restricting plastic production — which is ultimately the most important solution to the plastic pollution crisis — Oyewole suggested some additional actions lawmakers could take to keep chemical recycling in check. For example, they could ban the burning of toxic chemicals that are frequently found in plastics, such as PFAS. Prioritizing environmental justice could also help. One bill introduced in Arizona, for example, would create an environmental justice task force to ensure community-wide participation and input in proposals to build industrial facilities — like chemical recycling plants — in low-income communities and communities of color.

Expanded public education may also be needed, Oyewole added, in particular to offset the petrochemical industry’s inaccurate use of the word “recycling.” “Thus far, the plastic industry has succeeded in presenting these facilities as positive and necessary by using the misleading labels of ‘chemical’ or ‘advanced recycling,’” GAIA said in its report.

Singla, with NRDC, offered an alternative way to refer to the process, joking that she should have used “waste-to-fuel” throughout her own organization’s report. That way, “we could have abbreviated it WTF.”

Cigarette butts: how the no 1 most littered objects are choking our coasts

Cigarette butts: how the no 1 most littered objects are choking our coasts An estimated 4.5tn tobacco filters are littered each year and many end up in oceans with deadly consequencesSome count long stretches of powdery white sand, others are fringed by dramatic cliffs. But no matter the beach or its location, there’s little escape from the blight that plagues many of them: cigarette butts.Spain’s nearly 5,000 miles of coastline are no exception. “On beaches where smoking is allowed, unfortunately cigarette butts continue to rank as the most found waste product and the one with the most significant impact,” says Inés Sabanés a Spanish lawmaker with the Más País–Equo governing coalition.The coalition was the driving force behind a new legal framework that came into effect in April, which allows local councils to ban smoking on their beaches and impose fines of up to €2,000 (£1,700).

Learning more about the ocean's problems can inspire solutions

It’s easy to take the ocean for granted. The deep blue is crucial to things we do every day without thinking. We breathe. We eat and drink. We buy something that’s made far from where we live. The ocean contributes to all those things. Not thinking about what the ocean does for us would be okay if its gifts were limitless. But they are not. And the actions of humans — nearly 8 billion of us — are threatening resources we can’t do without.Thankfully, a growing number of people are focused on safeguarding the ocean. Scientists, lawmakers, businesses and nonprofit groups are among those raising awareness of problems such as plastic pollution, bycatch and ocean acidification. They aren’t only highlighting problems, however. They are developing solutions. Small success stories are building hope and encouraging more people to get involved.We created a special collection of KidsPost stories because we know that when you think about the ocean, you realize how valuable it is. We have proof. Readers recently answered our request for short ocean appreciations, several of which we feature below. Reflecting is a good first step. We hope the additional stories and photos deepen your understanding of the ocean’s problems and inspire you to be part of the solutions.Reflections by young writersWhat I appreciate most about the ocean is the diversity of life it supports, from enormous blue whales to tiny, but ever so important, corals. I love the beauty, architecture and liveliness of all the animals, plants and others who dwell under the sea.— Brice Claypoole, 14, Longboat Key, FloridaTreasure, transportation and food. All of these good things come from the ocean. The ocean lets us explore and express ourselves. It gives us food and all of these amazing things that come from the ocean. It allows us to show the world what we can do together!— Owen Bairley, 9, Fredericksburg, VirginiaI appreciate ocean animals. They’re fun to watch! I’ve seen a movie called “Soul Surfer,” and in it, somebody’s attacked by a shark. That made me realize ocean life is hard. They struggle to survive. That made me appreciate them even more because, like me, ocean animals face many struggles.— Hailey Somsel, 10, New York, New YorkAn Ode to the OceanEvolution beginsThe ocean is always changingCreatures evolveOctopus carrying shells, the horseshoe crabCoral reefs, puffer fish, sharks, eelsMedicine and foodTo the past, to the present, to the futureIt will always be there tomorrow, if you take care of it today.— Thomas Gallagher, 9, Potomac, MarylandI appreciate the beauty and the diversity of marine animals, the waves that make the most amazing sound as they crash ashore, the fish that give us food when we don’t give anything in return, but most of all the memories and fun that we have at the beach.— Layli Ziraknejad, 12, Reston, VirginiaThe ocean is vital for us human beings. Without the ocean we couldn’t survive. Not only do 12 percent of people need the ocean for food, but a whopping 50 percent of the world’s oxygen comes from phytoplankton in the ocean. The ocean’s my MVP for being the human race’s life support.— Colin Sellers, 10, Sarasota, FloridaThe ocean is a happy place for all. Anyone can go at anytime. In the summer you can cool down and relax in the sun. In the winter you can watch the waves crash fiercely on the sand. The ocean never closes its doors. It gives us so much.— Madelyn Legeer, 10, Silver Spring, MarylandWhat I appreciate most about the ocean is that it gives a home to one of my favorite animals, manta rays. They are very calm and peaceful, but they are endangered. When I grow up, I want to be a scientist so I can help them not be endangered anymore.— Lily Guder, 7, Alexandria, VirginiaWhether it is dolphins jumping out of the water, droplets like diamonds as they hit the sun, or it is evening sunsets that fade from burning yellow to brilliant purple, I love the ocean’s beauty.— Sara Husain, 13, Ruskin, FloridaA Mysterious WorldUnderneath the ocean waves, there is a whole world of mysteries waiting to be explored. Some kinds of marine life like the giant squid are very rare, and we barely have any photos or evidence. Scientists are still working hard to learn things we don’t know about.— Juno Wu, 11, Falls Church, VirginiaI love the ocean because it’s the perfect place for me to think when I’m mad. I just love the clear blue water and the ocean sounds. It really calms me, and I just think the ocean animals are lovely.— Charlie Miller, 9, Odenton, MarylandThe ocean is a beautiful place that should be protected. The different colors of the water, the size of the waves, no two beaches are the same. All of these put together make me eager to go to the beach — to swim, to see the water, to enjoy.— Eric Toop, 12, Westerville, OhioI like that the mama whales protect baby whales from predators. I like the clownfish’s home. I like how the scuba divers save the fish.— Doreen Wills, 6, Duluth, MinnesotaI appreciate the ocean because I like to see the sea turtles and dolphins. I like to listen to the waves that are on the beach. It sounds peaceful and helps me relax. The ocean also brings shells up to the beach that I can find.— Maxton McCarthy, 6, Tampa, Florida

Replacing lead water pipes with plastic could raise new safety issues

A plumber with Chicago’s department of water management attaches a copper service line to an existing lead service while he and others worked to replace water main lines in 2016. Credit: Anthony Souffle/Chicago Tribune/Tribune News Service via Getty ImagesAdvertisement

A landmark federal commitment to fund the elimination of a toxic national legacy—lead drinking water pipes—promises to improve the public health outlook for millions of people across the U.S. But it also presents communities with a thorny choice between replacement pipes made of well-studied metals such as copper, steel or iron and more affordable but less-studied pipes made of plastic.

Under a $15-billion allocation in last year’s Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, dedicated funding has started flowing to U.S. states to pay for removing and replacing so-called lead service lines—pipes that connect underground water mains with buildings and their plumbing systems. The funds could cover the replacement of about a third of the nation’s estimated six million to 10 million such lines.

In March the anticipated surge of lead-pipe-replacement work prompted a group of 19 health and environmental advocacy organizations headed by the nonprofit Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) to publish a set of guiding principles for lead-line replacement. Amid numerous recommendations related to community involvement, safety and economic justice, the document takes a stand against swapping in pipes made of plastic and calls for copper lines instead.

Although there is a consensus in the health and biomedical community that lead service lines should be replaced, many water quality and health questions about plastic drinking water pipes in the U.S. are unresolved or have yet to be addressed, a number of experts say. Some industry representatives disagree with recent findings that suggest links between plastic drinking water pipes and health issues. The situation could prove frustrating and confusing for utilities and consumers as communities receive federal funds for replacements—and must then consider the many dimensions of choosing the safest and most suitable new pipes for their region.

Service lines are commonly made of copper, iron, steel or one of several types of polyethylene or polyvinyl chloride (PVC), according to various sources. In the next decade up to 35 percent of U.S. utilities’ spending on drinking water distribution will go toward plastic pipes, says Bluefield Research, a firm that provides analyses of global water markets. Plastic materials such as PVC and high-density polyethylene (HDPE) are typically less expensive to purchase up front than more traditional materials such as copper, ductile iron and steel. So when measured in miles of distribution pipe, plastic is forecast to make up nearly 80 percent of the nation’s water pipe inventory by 2030, according to Bluefield.

It is very clear that there is no safe level of lead exposure, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and many medical and public health leaders. Taking in even low levels of lead from paint and drinking water causes several types of health issues, including intellectual deficits, particularly in children, as well as neurological and reproductive problems and increased risk of cardiovascular death.

With plastic pipes, the matter of potential drinking water contamination is less clear-cut. In the NRDC-led group’s lead-line-replacement principles, the copper-not-plastic item points to recent research suggesting that plastic pipes can potentially contaminate drinking water in three ways. The first is the release of chemicals into water from the pipe material, a process called leaching, which has been documented in several studies. The second route, called permeation, involves pollutants such as gasoline that can seep from groundwater or soils through the walls of plastic pipes, which has been noted in reports by the Environmental Protection Agency and the Water Research Foundation (formerly the Awwa Research Foundation). And finally, plastic pipes exposed to the high heat of wildfires are at risk for melting and other thermal damage. Plastic pipes damaged in wildfires could release toxic chemicals into drinking water, the NRDC document suggests, citing an October 2021 EPA fact sheet. The high heat of fires can degrade plastic pipes, valves and meters in drinking water distribution systems, potentially releasing volatile organic compounds (VOCs) into drinking water, the EPA document states. A 2020 study arrived at more explicit findings by revealing in lab tests that plastic pipes exposed to wildfire temperatures can release benzene, a carcinogen, and other VOCs into water.

Pipe material-related factors beyond those in the principles document can also contaminate drinking water. A July laboratory study by civil and environmental engineer Marc Edwards of Virginia Tech and his colleagues revealed that the growth of Legionella pneumophila, the water-borne bacterium that causes Legionnaires’ disease, varied with the pH of water, whether that water was in contact with cross-linked polyethylene (PEX) or copper pipes, and the presence of phosphate, which is used to control corrosion.

Some organizations associated with the plastic pipes industry are skeptical or dismissive of findings that link these pipes with potential drinking water quality and health concerns. Bruce Hollands, executive director of the Uni-Bell PVC Pipe Association, points to a 2015 environmental product declaration (EPD) that followed an assessment of seven PVC water and sewer pipe products by the International Organization of Standardization (ISO), a voluntary, nongovernmental standards organization. The declaration states, “PVC pipe and fittings are resistant to chemicals generally found in water and sewer systems, preventing any leaching or releases to ground and surface water during the use of the piping system. No known chemicals are released internally into the water system. No known toxicity effects occur in the use of the product.” An update due out in a few months will contain the same statement, Hollands says.

A similar position is held by a nonprofit organization called NSF (originally founded as the National Sanitation Foundation), which is one of several organizations to offer testing that can lead to certification of manufacturers’ drinking water pipes and other system components under a standard called NSF/ANSI/CAN 61 Drinking Water System Components–Health Effects, or Standard 61. “We are not aware of credible evidence that would discourage the use of plastic pipe or other products that are certified to NSF/ANSI/CAN 61 in drinking water systems,” NSF said in a statement to Scientific American.

Standard 61 is determined by a committee of manufacturers, toxicologists, water utilities and federal and state regulatory officials, said NSF (which is unrelated to the U.S. National Science Foundation). The standard is recognized by the nonprofit American National Standards Institute (ANSI) and the Standards Council of Canada (a federal “Crown corporation”). The EPA “has supported the development of independent third-party testing standards for plumbing materials” under Standard 61, the agency says. Its only safety requirement for pipes and other plumbing materials is that they are free of lead. Nearly all U.S. states require utilities to use pipes and other water distribution system products that are certified to Standard 61.

Consumers with questions about the safety of pipes that are in contact with drinking water should focus on individual products that are certified to appropriate standards rather than the materials that pipes are made of, NSF wrote in its statement to Scientific American. Some material-related trends have emerged in examinations of specific contamination routes, however.

Permeation of metal pipes is “extremely rare,” says Edwards, who in 2015 pinned down the cause of high lead levels amid Flint, Mich.’s water crisis. In contrast, gasoline and solvents can permeate polyethylene pipes, and pure benzene and other dangerous organic compounds also permeate PVC pipe without rubber gaskets (although gasoline does not), a Water Research Foundation report states. In a 2009 document, the Plastics Pipe Institute, a trade organization, called the conclusions of the report “inconclusive and perhaps misleading.”

All pipes can leach their constituent materials to some extent, according to a 2006 National Research Council report. Corrosion control can help to manage copper that leaches from pipes made of that metal, Edwards says. Various types of plastic pipes can release compounds that are potentially toxic or carcinogenic, studies have found. Yet the EPA has set no legally enforceable federal standards for many of these contaminants if they turn up in drinking water (under the Safe Drinking Water Act, state standards for contaminants must be at least as stringent as federal ones). The current questions that need to be answered are which pipe-related contaminants get into drinking water, the extent to which they might affect water quality and human health, and whether any industry-independent researchers or government regulators are looking for specific concerning contaminants at all, especially in the case of plastic pipes.

Rather than advocating for one material over another for these service lines, many U.S. environmental engineers say the choice of material for any given underground water pipe should depend on factors such as whether a pipe will be flushed before use; how regularly the pipe will be used; whether the pipe is going in near an underground tank storing gasoline, sewage or other harmful material; and conditions such as the water pH and temperature.

For example, in a 2020 study funded by the EPA, environmental engineer Patrick Gurian of Drexel University and his colleagues found statistically significant higher concentrations of total organic carbon (TOC), a nonspecific water quality measure, in some PEX pipes than in copper ones. Organic carbon in a water supply can come from decaying leaves and other natural sources and can leach from synthetic sources such as a plastic pipe.

But the characteristics of the study’s two individual water systems (in Philadelphia and Boulder, Colo.) varied by water source, disinfectant used and average pH, among other factors. Such variations are unavoidable across water systems. “Plastic pipe can leach TOC, but this can be addressed through quality control measures such as proper testing and certification,” Gurian says. “Engineering is about managing risks and making tradeoffs. I am not aware of information that would justify banning all plastics from use as pipe materials.” The Plastic Pipe and Fittings Association, a trade association, wrote in a statement to Scientific American that “plastic pipe has been extensively studied for all sorts of supposed maladies since the early 1980s.”

Some researchers say plastic pipes in the U.S. have not yet undergone the same degree of water quality and health scrutiny as pipes made of copper, iron, steel and cement. With these so-called legacy materials, methods to prevent or remedy leaching, permeation and other issues are well known, says environmental engineer Andrew Whelton of Purdue University. But that is not the case with plastic pipes. Colleges and graduate schools that train civil engineers and public health researchers have historically ignored the chemistry and manufacturing of plastic in their curricula on water quality issues, Whelton says.

Scott Coffin, a research scientist at California’s State Water Resources Control Board, studies the impacts of microplastics in drinking water on human health, as well as the potential health impacts of endocrine-disrupting additives in water distribution systems. He agrees that more research is needed on water quality and plastic drinking water pipes. “Drinking-water-distribution-system contaminants resulting from plastic pipes are not explored very often,” Coffin says. “It’s sort of forgotten about, honestly, in the water industry.”

Whelton and his colleagues have actively pursued questions about potential contaminants in the water carried in plastic and other types of drinking water pipes. In a 2014 study, the team identified 11 PEX-related organic compounds, including toluene—one of 90 or so contaminants for which the EPA has set legal limits in drinking water—in the water that was in contact with PEX pipes installed in a six-month-old “net-zero energy” building. The compounds were not found in water entering the building. Two years later the team published a study that compared contaminants released by copper pipes and by 11 brands of a total of four types of plastic pipes. Microbial growth thresholds were exceeded in water in contact for the first three days of exposure with three of the brands of PEX pipe. Then, in a 2017 study, Whelton and other colleagues found that heavy metals, including copper, iron, lead and zinc accumulated as sediment and formed scales inside PEX drinking water pipes in a home’s one-year-old plumbing system.

None of these three studies, all funded by the U.S.’s NSF (the National Science Foundation) and performed with pipes marked as certified to Standard 61, was designed to make direct health claims, Whelton says. Instead they were meant to reveal potential contaminants—some of which could hold implications for water quality and health—that could be produced by interactions between drinking water and plastic pipes.

Each of the studies, however, drew the pointed attention of the other NSF (the nonprofit testing and certifying organization), which reported $123 million in revenue in 2020. On a voluntary basis, manufacturers of products ranging from water system components to microwave ovens may pay fees to NSF, or any of several other competitors, to assess whether products meet standards (which are often set in collaboration with NSF) and whether they merit certification. Such certification indicates that “an independent organization has reviewed the manufacturing process of a product and has independently determined that the final product complies with specific standards for safety, quality or performance,” according to NSF’s website.

In 2018 NSF released a document addressing Whelton and his colleagues’ 2014, 2016 and 2017 studies of plastic drinking water pipes, stating that the conclusions and data “have contributed to misinformation and confusion about these products.”

Whelton says there is no misinformation in the studies, each of which was peer-reviewed. NSF “claimed information was not included in the studies when it actually was,” he says, adding that the organization’s document itself “is an example of misinformation and should be ignored.”

When it comes to drinking water safety and plastic, that is largely what the organizations that signed onto the lead-service-line-replacement principles headed by NRDC have done, putting their trust elsewhere than the plastic industry and pipe testing and certification organizations. The NRDC-led group’s document of principles links to studies and reports by the EPA, the Water Research Foundation and academic researchers. And the document states that its call for copper replacement pipes rather than plastic ones draws on recommendations and concerns from the Healthy Building Network, the International Association of Fire Fighters and United Association, a plumbers’ and pipe fitters’ union. As Yvette Jordan of the Newark Education Workers Caucus, an organization that signed the document, puts it, “When you have so many people—so many organizations, especially—when they agree…, shouldn’t you take notice and say, ‘Okay, we should probably reexamine this … and use copper and not plastic’?”

Rights & Permissions

ABOUT THE AUTHOR(S)Journalist Robin Lloyd, a contributing editor at Scientific American, is president of the Council for the Advancement of Science Writing’s board of directors. Follow Robin Lloyd on Twitter. Credit: Nick HigginsRecent Articles by Robin LloydGazelle Traveled Distance of Nearly Half Earth’s Circumference in Five YearsPeople Are Getting COVID Shots Despite HesitationCOVID Smell Loss and Long COVID Linked to Inflammation

Greece's islands are zero-waste laboratories

Before the tiny Greek island of Tilos became a big name in recycling, taverna owner Aristoteles Chatzifountas knew that whenever he threw his restaurant’s trash into a municipal bin down the street it would end up in the local landfill.The garbage site had become a growing blight on the island of now 500 inhabitants, off Greece’s south coast, since ships started bringing over packaged goods from neighboring islands in 1960.Six decades later, in December last year, the island launched a major campaign to fix its pollution problem. Now it recycles up to 86 percent of its rubbish, a record high in Greece, according to authorities, and the landfill is shut.Chatzifountas said it took only a month to get used to separating his trash into three bins — one for organic matter; the other for paper, plastic, aluminium and glass; and the third for everything else.“The closing of the landfill was the right solution,” he told the Thomson Reuters Foundation. “We need a permanent and more ecological answer.”Tilos’ triumph over trash puts it ahead in an inter-island race of sorts, as Greece plays catch-up to meet stringent recycling goals set by the European Union (EU) and as institutions, companies and governments around the world adopt zero-waste policies in efforts to curb greenhouse gas emissions.“We know how to win races,” said Tilos’ deputy mayor Spyros Aliferis. “But it’s not a sprint. This is the first step (and) it’s not easy.”The island’s performance contrasts with that of Greece at large. In 2019, the country recycled and composted only a fifth of its municipal waste, placing it 24th among 27 countries ranked by the EU’s statistics office.That’s a far cry from EU targets to recycle or prepare for reuse 55 percent of municipal waste by weight by 2025 and 65 percent by 2035.Greece has taken some steps against throwaway culture, such as making stores charge customers for single-use plastic bags.Still, “we are quite backward when it comes to recycling and reusing here,” said Dimitrios Komilis, a professor of solid waste management at the Democritus University of Thrace, in northern Greece.Recycling can lower planet-warming emissions by reducing the need to manufacture new products with raw materials, whose extraction is carbon-heavy, Komilis added.Workers sort through municipal waste at a Polygreen factory located on the island of Tilos, Greece, on June 30, 2022. Credit: Thomson Reuters Foundation / Sebastien MaloGetting rid of landfills can also slow the release of methane, another potent greenhouse gas produced when organic materials like food and vegetation are buried in landfills and rot in low-oxygen conditions.And green groups note that zero-waste schemes can generate more jobs than landfill disposal or incineration as collecting, sorting and recycling trash is more labor-intensive.But reaching zero waste isn’t as simple as following Tilos’ lead — each region or city generates and handles rubbish differently, said researcher Dominik Noll, who works on sustainable island transitions at Vienna’s Institute of Social Ecology.“Technical solutions can be up-scaled, but socioeconomic and sociocultural contexts are always different,” he said.“Every project or program needs to pay attention to these contexts in order to implement solutions for waste reduction and treatment.”High-value trashTilos has built a reputation as a testing ground for Greece’s green ambitions, becoming the first Greek island to ban hunting in 1993 and, in 2018, becoming one of the first islands in the Mediterranean to run mainly on wind and solar power.For its “Just Go Zero” project, the island teamed up with Polygreen, a Piraeus-based network of companies promoting a circular economy, which aims to design waste and pollution out of supply chains.Several times a week, Polygreen sends a dozen or so local workers door-to-door collecting household and business waste, which they then sort manually.Antonis Mavropoulos, a consultant who designed Polygreen’s operation, said the “secret” to successful recycling is to maximize the waste’s market value.“The more you separate, the more valuable the materials are,” he said, explaining that waste collected in Tilos is sold to recycling companies in Athens.On a June morning, workers bustled around the floor of Polygreen’s recycling facility, perched next to the defunct landfill in Tilos’ arid mountains.They swiftly separated a colorful assortment of garbage into 25 streams — from used vegetable oil, destined to become biodiesel, to cigarette butts, which are taken apart to be composted or turned into materials like sound insulation.Organic waste is composted. But some trash, like medical masks or used napkins, cannot be recycled, so Polygreen shreds it, to be turned into solid recovered fuel for the cement industry on the mainland.More than 100 tons of municipal solid waste — the equivalent weight of nearly 15 large African elephants — have been sorted so far, said project manager Daphne Mantziou.Crushed by negative news? Sign up for the Reasons to be Cheerful newsletter.Setting up the project cost less than 250,000 euros ($255,850) — and, according to Polygreen figures, running it does not exceed the combined cost of a regular municipal waste-management operation and the new tax of 20 euros per ton of landfilled waste that Greece introduced in January.More than ten Greek municipalities and some small countries have expressed interest in duplicating the project, said company spokesperson Elli Panagiotopoulou, who declined to give details.No time to wasteReplicating Tilos’ success on a larger scale could prove tricky, said Noll, the sustainability researcher.Big cities may have the money and infrastructure to efficiently handle their waste, but enlisting key officials and millions of households is a tougher undertaking, he said.“It’s simply easier to engage with people on a more personal level in a smaller-sized municipality,” said Noll.When the island of Paros, about 200 km (124 miles) northwest of Tilos, decided to clean up its act, it took on a city-sized challenge, said Zana Kontomanoli, who leads the Clean Blue Paros initiative run by Common Seas, a UK-based social enterprise.The island’s population of about 12,000 swells during the tourist season when hundreds of thousands of visitors drive a 5,000 percent spike in waste, including 4.5 million plastic bottles annually, said Kontomanoli.In response, Common Seas launched an island-wide campaign in 2019 to curb the consumption of bottled water, one of a number of its anti-plastic pollution projects.Using street banners and on-screen messages on ferries, the idea was to dispel the common but mistaken belief that the local water is non-potable.The share of visitors who think they can’t drink the island’s tap water has since dropped from 100 percent to 33 percent, said Kontomanoli.“If we can avoid those plastic bottles coming to the island altogether, we feel it’s a better solution” than recycling them, she said.Another anti-waste group thinking big is the nonprofit DAFNI Network of Sustainable Greek Islands, which has been sending workers in electric vehicles to collect trash for recycling and reuse on Kythnos island since last summer.Project manager Despina Bakogianni said this was once billed as “the largest technological innovation project ever implemented on a Greek island” — but the race to zero waste is now heating up, and already there are more ambitious plans in the works.Those include CircularGreece, a new 16-million-euro initiative DAFNI joined along with five Greek islands and several mainland areas, such as Athens, all aiming to reuse and recycle more and boost renewable energy use.“That will be the biggest circular economy project in Greece,” said Bakogianni

Pika wants to makes cleaning reusable diapers as easy as throwing out disposable ones

Babies use 6,500 disposable diapers before they’re potty trained, and cloth diapers are labor intensive to clean. Pika hopes to eliminate both that waste, and all that work.

[Photo: courtesy Pika]

By

Collision course: Will the plastics treaty slow the plastics rush?

The interlacing pipelines of a massive new plastics facility gleam in the sunshine beside the rolling waters of the Ohio River. I’m sitting on a hilltop above it, among poplars and birdsongs in rural Beaver County, Pennsylvania, 30 miles north of Pittsburgh. The area has experienced tremendous change over the past few years — with more soon to come.

The ethane “cracker plant” belongs to Royal Dutch Shell, and after 10 years and $6 billion it’s about to go online. Soon it will transform a steady flow of fracked Marcellus gas into billions of plastic pellets — a projected 1.6 million tons of them per year, each the size of a pea. From this northern Appalachia birthplace, they’ll travel the globe to make the plastic goods of modern life, from single-use bags to longer-lasting sports equipment.

The factory. Photo: Tim Lydon

The plant’s construction has lifted a hardscrabble local economy, but it also embodies an epic global struggle.

Earlier this year and half a world away, United Nations negotiators meeting in Kenya pledged to draft a legally binding international plastics treaty by 2024. Many hope it will cap global plastics production while also addressing plastic’s impacts on environments and people. When treaty talks begin later this year, they’ll have everything to do with plants like this one and hundreds like it popping up around the world.

But the plants, and their powerful backers in the plastics and fossil fuel industries, will also shape the talks.

“They will work very hard to make sure that the treaty is not effective,” says Judith Enck, former EPA regional administrator in the Northeast and president of Beyond Plastics, a nonprofit that seeks to stem plastics pollution.

Enck describes plastics as a “Plan B” for fossil fuels, at a time when renewables and efficiency erode industry profits. To Shell and its peers, plastics production can secure assets like Pennsylvania’s seemingly bottomless Marcellus gas field, which might otherwise go untapped as the world retreats from fossils in the face of climate change.

Plastic waste collects in a drainage ditch in 2021. Photo: Ivan Radic (CC BY 2.0)

But Enck notes that plastics also drive climate change. A 2021 Beyond Plastics report estimated that U.S. plastics production now puts out heat-trapping emissions equivalent to 116 coal-fired power plants. With more facilities like the one in Pennsylvania coming, the report says, U.S. plastics could exceed the climate impact of domestic coal-fired energy by 2030.

The International Panel on Climate Change and others echo the concern, saying that global plastics production could reach 20% of oil consumption in the coming decades, surpassing concrete, food waste, and other heavy heaters. Today the United States, China, Saudi Arabia and Japan lead the trend as the world’s top producers of plastic.

Waste is another concern. With little plastic ever recycled, it’s now found from the deepest oceans to the highest mountains. One estimate has its volume in marine waters surpassing that of fish by mid-century. And while images of plastics in the bellies of birds, fish and whales have become old news, new research shows microplastics ingested by trees, deposited on Arctic sea ice, and entering the developing brains of human babies.

Plastic waste also emits greenhouse gases as it breaks down or when it’s incinerated.

Enck also calls it an environmental justice issue, with plastics production and disposal disproportionately impacting poorer communities.

But Enck sees rising awareness, too.

“I have met climate change skeptics, but I have never met a plastic pollution skeptic,” she says. People see the problem firsthand and want governments to act.

To her, one solution to the crisis is a binding international treaty that addresses plastics production, use and disposal.

My hilltop perch sits near new townhomes, and residents of the community come and go. They include two older men who grew up nearby and have come to release happy birthday balloons, which they then watch fade into blue sky through binoculars.

Around the same time Jeff Coleman, candidate for lieutenant governor, arrives with local officials to film a campaign spot. They discuss “downstream” manufacturers that could spring up near the plant, which itself will soon employ 600 people.

Below us the plant dominates the landscape. Neatly squeezed onto 400 acres, it hosts its own gas power plant, a string of cylindrical polyethylene reactors, and miles of convoluted pipeline, along with warehouses, offices and room for more than 3,000 railcars to shuttle the tiny pellets away.

To build it, Shell remediated an old zinc smelter, redirected a local highway, built a railroad spur and laid the 97-mile Falcon Ethane Pipeline to access nearby Marcellus gas. During construction, more than 8,000 workers clocked in every day.

Land clearing at the Shell site in 2016. Photo (uncredited) via Gov. Tom Wolf/Flickr (CC BY 2.0)

“It put our county on the map,” says Beaver County commissioner Jack Manning.

He says construction sustained pandemic-strapped businesses and attracted investment in hotels, malls and even housing, like the new townhomes overlooking the plant. Manning also expects years of both direct and indirect job creation.

For many community leaders of this one-time manufacturing epicenter, which has struggled since steel moved away in the 1980s, these are welcome developments.

But others counter Manning’s rosy assessments, pointing to continued economic stagnation in the region since construction began. Still, state and local governments have bet big on Shell by awarding it the largest corporate tax break in Pennsylvania history.

The government support matters. In the United States and other countries that will soon negotiate the global plastics treaty, local investment translates into political power for plastics. That was clear when then-President Trump gave a 2019 campaign-style speech at the Shell plant, touting his commitment to U.S. manufacturing.

Manning says that behind such support are real benefits for the community, including the young families he sees buying townhomes and reinvigorating local communities.

As for environmental effects, Manning, who spent 35 years in the petrochemical industry, believes Shell’s state-of-the-art technology will protect local air and waters. He shares activists’ broader concerns about climate change and ocean pollution, but says the pellets made here will create products that improve lives, such as replacement knee joints, lightweight parts for electric cars and packaging that prevents food spoilage.

And he’s confident a global plastics treaty won’t hurt locally. If anything, global initiatives to reduce plastic production could secure demand from existing plants by limiting the construction of new ones, he says.

Jace Tunnell of the University of Texas Marine Science Institute offers another take.

In 2018 Tunnell discovered plastic pellets — called nurdles in the plastic-waste world — washed up on local beaches. When he learned they came from nearby plastics facilities, he created the nonprofit Nurdle Patrol to enlist citizens in monitoring pellet pollution along the Gulf of Mexico. The work is raising awareness and contributing to stricter permitting rules.

Nurdles and other plastic waste at a beach cleanup event. Photo: Hillary Daniels (CC BY 2.0)

Groups in Beaver County have since taken similar action to gather baseline environmental data before the Shell plant goes online.

“I haven’t seen a facility yet where there aren’t pellets in the environment,” says Tunnell. Their small size enables dispersal by wind, rain, storm drains and the pneumatic equipment that blows them onto railcars at production facilities. They can also wind up along railroad routes, at shipyards and in the ocean, depending on shipping practices.

Tunnell offers the example of former Gulf of Mexico shrimper Diane Wilson, who in 2019 won a $50 million settlement from a Formosa plastics facility in Texas that discharged billions of pellets and other pollutants.

And he points to a 2021 Sri Lankan cargo ship disaster that left beaches knee-deep in nurdles.

“They’re still cleaning them up,” he says.

Events like that have contributed to a tide of negative press that — along with inflation, the pandemic and other factors — have slowed the plastics boom. That’s evident in Pennsylvania. Only a few years ago, plastics makers had sketched out five new plants for the region to tie into Marcellus gas, plus two ethane-storage facilities. But three plants are now canceled, and neither storage facility has been built.

Governmental pushback, including momentum toward a global treaty, is also mounting, as seen by China’s 2017 decision to stop importing plastic waste for recycling. That policy change stranded plastic waste in U.S. communities and has contributed to federal and state efforts to hold retailers of single-use plastics accountable for the waste, something the European Union achieved in 2021.

For its part, the plastics industry claims a positive economic impact and commitments to environmental safety, which include its voluntary Operation Clean Sweep, designed to minimize pellet pollution. Shell representatives in Pennsylvania did not respond to interview requests but cited their participation in Clean Sweep and directed questions to their website, which describes mitigations for noise, air pollution and other plastics production issues.

But for Enck, industry-led initiatives fall short. She believes they distract from climate, equity, and other broader problems that she hopes are addressed in upcoming treaty talks.

As the treaty framework came together last February, industry allies pushed for an emphasis on waste management, including mitigating marine debris and improving recycling, which remains technologically difficult.

But delegates from Rwanda and Peru successfully advanced a more ambitious resolution that will consider the full life cycle of plastics, including production, disposal and its pollution impact on all environments, not just oceans. The resolution’s inclusion of a possible cap on virgin plastics production was supported by letters from international scientists and corporations such as Walmart and Coca-Cola.

In March delegates from 175 counties approved the Rwanda-Peru framework. Procedures and timelines were established at June meetings in Senegal, and negotiations are slated to begin in Uruguay in November. Although a treaty is expected in 2024, its true effect will depend on ratification from the United States and other top plastics producers and whether member nations will adhere to it.

In the meantime, political and market forces will continue determining how many more facilities like Pennsylvania’s Shell plant are built.

As I leave my Beaver County hillside, I ask the two men what will become of the balloons they’re releasing. They look at me for a moment, then one tells me with a shrug that they’ll eventually explode and fall to the ground.

That reminds me of something Enck said: “We’re leaving a mess for future generations.”

Get more from The Revelator. Subscribe to our newsletter, or follow us on Facebook and Twitter.

How to Turn Off the Tap on Plastic Waste

Environmentalists say policies limiting single-use plastics are necessary to curb North Carolina's growing microplastics problem

By Will Atwater

An environmental advocacy group in Durham has been pushing for a county-wide proposal to put a 10-cent fee on single-use plastic bags. Activists across the state have been eagerly watching to see if Durham’s local government officials will move forward on what would be the only policy on the books in North Carolina aimed at preventing plastic waste from entering the environment.

Advocates had hoped to see the issue discussed at a Durham Joint City-County Committee meeting on Tuesday, but due to a technical issue, it seems the bag fee proposal will be pushed off to a later date. Meanwhile, environmentalists say these are the kinds of policies needed statewide to combat the ever-growing microplastic waste problem.

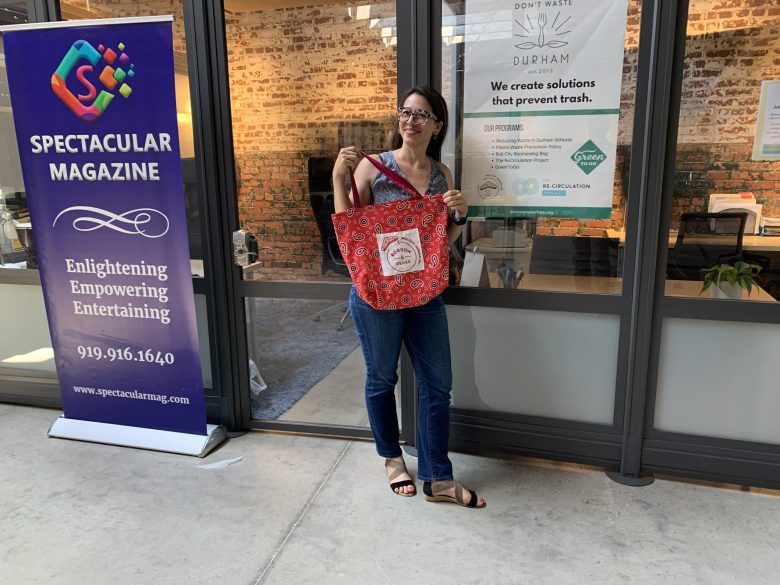

“We have to all work together, but I’m sick of just the continual focus on mitigation. Can we please also spend equal energy on prevention?” said Crystal Dreisbach, founder of Don’t Waste Durham, the nonprofit organization behind the bag fee proposal which works to prevent trash at the source.

The bag fee proposal in Durham is the kind of policy advocates at Waterkeepers Carolina, a nonprofit aimed at preserving the state’s waterways, say would be really helpful. The waterkeepers are in a downstream-battle to capture a constant flow of plastic waste before it enters the ocean. And they’re losing.

The amount of plastic waste entering North Carolina’s waterways and soil is outpacing their capacity to remove it.

“The only way we’re going to make any kind of headway with this type of pollution problem is prevention, prevention, prevention,” said Lisa Rider, director of Coastal Carolina Riverwatch.

“And policies are certainly at the top of the hierarchy in doing so.”

Don’t waste Durham’s plan

In 2021, Duke Environmental Law and Policy Clinic developed the proposed 10-cent bag fee on behalf of the local nonprofit Don’t Waste Durham. A white paper produced by the law clinic and published on the nonprofit’s website states that while customers are given free plastic or paper bags at check-out counters, there are significant costs associated with using these materials.

“These bags have very real costs for our community: they contribute to litter on streets and in waterways, clog storm drains, take unlimited landfill space, and wreak havoc on recycling infrastructure.”

The white paper also claims that it costs Durham more than $86,000 per year in related fees.

In drafting the plan, Dreisbach wanted to make sure the proposed ordinance did not penalize low-income residents. Durham shoppers who are on an assistance program, such as WIC or SNAP, would be exempt from the bag fee, she explained.

Don’t Waste Durham also supports an initiative called Bull City Boomerang Bag whose mission is to assist communities in “tackling waste at its source.” Durham businesses such as Part & Parcel, Durham Co-op Market and Pennies for Change are some shops that offer free Bull City Boomerang Bags to their customers. A volunteer staff uses donated fabric to make the bags, which are then given away.