While we know where the plastics came from, the origin of this particular tar wasn’t clear. But generally speaking, whenever oil spills, it floats around and partially evaporates, thickening over time into tar balls, which then wash ashore. It’s basically super-toxic Play-Doh. “Once it gets stuck to the rock, the wave brings microplastics or any litter and pushes it into this Play-Doh,” says Hernández-Borges. “Microplastics arrive constantly, constantly, constantly. The microplastics that we’re finding in the tar are the same ones that we’re finding on the coast.” These tiny bits add to the noxiousness of plastitar, because plastics are loaded with thousands of their own chemicals, many of which are known to be toxic to humans and other animals. These researchers can’t yet say what effect the plastitar might have on the organisms living on the beaches of the Canary Islands. But the problem could be twofold. “If there were algae or whatever, those rocks are completely covered by that, so they will die for sure,” says Hernández-Borges. Secondly, plastitar is darker than the rock, meaning it absorbs more of the sun’s energy. “If you touch it, you will see that it’s also very, very, very hot,” he says. That could significantly raise temperatures at ground level, with unknown implications for the organisms that live there. In a previous study on a remote island in the Pacific, a separate team of researchers found that plastic particles raised the temperature of beach sand. That could imperil sea turtles, whose sex is determined by the temperature of the sand the eggs are laid in—if it gets too hot, they’ll all turn out female, which is no good for the sexual reproduction of a species.The discovery of plastitar adds yet another layer of complexity to the problem of oceanic plastic pollution. For a long while, environmentalists were primarily concerned with the big stuff, like floating bottles and bags. It wasn’t until the early 2000s that scientists started investigating microplastics in earnest, subsequently finding that almost the entirety of Earth is tainted. The particles are blowing in the atmosphere and reaching the highest mountains. Up in the sky, they may be having a climate effect—although it’s not clear if they will ultimately help heat or cool the planet. People are eating and drinking loads of microplastics, and babies are drinking still more in their formula, but scientists are only beginning to investigate what that might mean for human health.Even more recently, researchers have been discovering “new plastic formations,” of which plastitar is only the latest. When plastic burns in beach campfires, for instance, it forms a gnarly matrix of polymer mixed with sand and other debris. “Plasticrust” forms in a similar way to plastitar, when waves smash plastic into coastal rocks, only without the involvement of tar. (High outdoor temperatures heat the rocks, which can help the synthetic material meld into them.) And scientists are beginning to investigate what they’re calling anthropoquina, or new sedimentary rock made of plastic and other human-made materials. “If someone in thousands of years finds one of these rocks, they will find probably plastic, and they will see how we lived,” says Hernández-Borges. “So that’s sort of a geological record.” And—because someone is going to think it—to be abundantly clear, we should not take inspiration from plastitar to rid the sea of microplastics. “I read this and went nooo,” says Allen. “Some idiot out there is going to go: Just put oil all over the top of the surface, and then clean it up. But no.”

Category Archives: News

‘Plastitar’ is the unholy spawn of oil spills and microplastics

While we know where the plastics came from, the origin of this particular tar wasn’t clear. But generally speaking, whenever oil spills, it floats around and partially evaporates, thickening over time into tar balls, which then wash ashore. It’s basically super-toxic Play-Doh. “Once it gets stuck to the rock, the wave brings microplastics or any litter and pushes it into this Play-Doh,” says Hernández-Borges. “Microplastics arrive constantly, constantly, constantly. The microplastics that we’re finding in the tar are the same ones that we’re finding on the coast.” These tiny bits add to the noxiousness of plastitar, because plastics are loaded with thousands of their own chemicals, many of which are known to be toxic to humans and other animals. These researchers can’t yet say what effect the plastitar might have on the organisms living on the beaches of the Canary Islands. But the problem could be twofold. “If there were algae or whatever, those rocks are completely covered by that, so they will die for sure,” says Hernández-Borges. Secondly, plastitar is darker than the rock, meaning it absorbs more of the sun’s energy. “If you touch it, you will see that it’s also very, very, very hot,” he says. That could significantly raise temperatures at ground level, with unknown implications for the organisms that live there. In a previous study on a remote island in the Pacific, a separate team of researchers found that plastic particles raised the temperature of beach sand. That could imperil sea turtles, whose sex is determined by the temperature of the sand the eggs are laid in—if it gets too hot, they’ll all turn out female, which is no good for the sexual reproduction of a species.The discovery of plastitar adds yet another layer of complexity to the problem of oceanic plastic pollution. For a long while, environmentalists were primarily concerned with the big stuff, like floating bottles and bags. It wasn’t until the early 2000s that scientists started investigating microplastics in earnest, subsequently finding that almost the entirety of Earth is tainted. The particles are blowing in the atmosphere and reaching the highest mountains. Up in the sky, they may be having a climate effect—although it’s not clear if they will ultimately help heat or cool the planet. People are eating and drinking loads of microplastics, and babies are drinking still more in their formula, but scientists are only beginning to investigate what that might mean for human health.Even more recently, researchers have been discovering “new plastic formations,” of which plastitar is only the latest. When plastic burns in beach campfires, for instance, it forms a gnarly matrix of polymer mixed with sand and other debris. “Plasticrust” forms in a similar way to plastitar, when waves smash plastic into coastal rocks, only without the involvement of tar. (High outdoor temperatures heat the rocks, which can help the synthetic material meld into them.) And scientists are beginning to investigate what they’re calling anthropoquina, or new sedimentary rock made of plastic and other human-made materials. “If someone in thousands of years finds one of these rocks, they will find probably plastic, and they will see how we lived,” says Hernández-Borges. “So that’s sort of a geological record.” And—because someone is going to think it—to be abundantly clear, we should not take inspiration from plastitar to rid the sea of microplastics. “I read this and went nooo,” says Allen. “Some idiot out there is going to go: Just put oil all over the top of the surface, and then clean it up. But no.”

Scientists report ‘heartening’ 30% reduction in plastic pollution on Australia’s coast

Scientists report ‘heartening’ 30% reduction in plastic pollution on Australia’s coast CSIRO researchers say efforts to raise public awareness have quickly led to improvements in the environment Get our free news app; get our morning email briefing The amount of plastic pollution on Australia’s coast has decreased by up to 30% on average as a …

Australia's coastal plastic pollution decreased by 29%

Credit: MarkPiovesan/Getty Images

Plastic pollution is an escalating global problem. Australia now produces 2.5 million tonnes of plastic waste each year, while world-wide production is expected to double by 2040.

This pollution doesn’t just accumulate on our beaches: it can be found on land and other marine environments (heard of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch?)

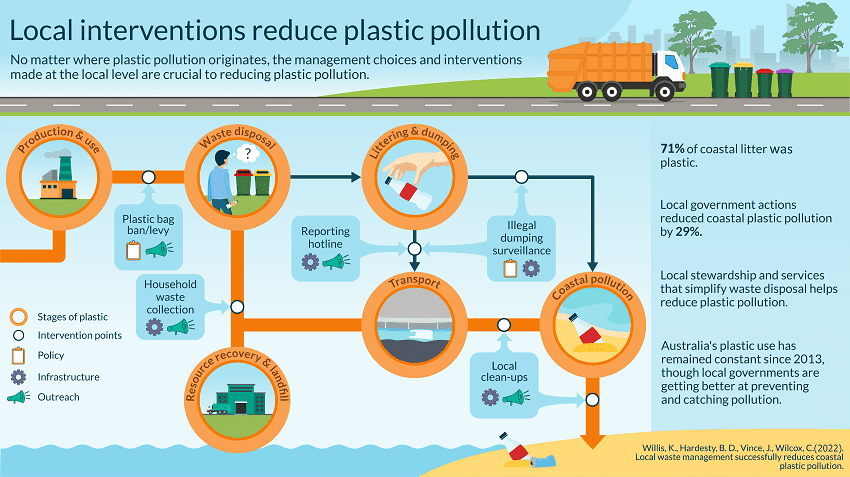

But according to a new study by Australia’s national science agency, CSIRO, plastic pollution on Australia’s coasts has decreased by 29% since 2013.

The study, which assessed waste reduction efforts in Australia and their effect on coastal pollution, highlights that although Australia’s plastic use has remained constant since 2013, local governments are getting better at preventing and cleaning up pollution.

“Our research set out to identify the local government approaches that have been most effective in reducing coastal plastics and identify the underlying behaviours that can lead to the greatest reduction in plastic pollution,” says lead researcher Dr Kathryn Willis, a recent PhD graduate from the University of Tasmania.

“Whilst plastic pollution is still a global crisis and we still have a long way to go, this research shows that decisions made on the ground, at local management levels, are crucial for the successful reduction of coastal plastic pollution,” she adds.

The study has been published in One Earth.

Local government approaches work

The new research builds upon extensive 2013 CSIRO coastal litter surveys with 563 new surveys and interviews with waste managers across 32 local governments around Australia completed in 2019.

The results found that, although there was a decrease in the overall national average coastal pollution by 29%, some surveyed municipalities showed an increase in local litter by up to 93%, while others decreased by up to 73%.

Since global plastic pollution is driven by waste reduction strategies at a local level (regardless of where the pollution originates), researchers then focused on identifying which local government approaches had the greatest effect on these levels of coastal pollution.

Get an update of science stories delivered straight to your inbox.

To do this they sorted local government waste management actions into three categories of human behaviour, including:

Planned behaviour – strategies like recycling guides, information and education programs, and voluntary clean-up initiatives.Crime prevention – waste management strategies like illegal dumping surveillance and beach cleaning by local governments.Economic – actions like kerb-side waste and recycling collection, hard waste collections and shopping bag bans.

Graphical abstract ofthe study. Credit: Willis et al (2022) DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oneear.2022.05.008

They found that retaining and maintaining efforts in economic waste management strategies had the largest effect on reducing coastal litter.

“For example, household collection services, where there are multiple waste and recycling streams, makes it easier for community members to separate and discard their waste appropriately,” says co-author Dr Denise Hardesty, a principal research scientist at CSIRO Oceans and Atmosphere.

“Our research showed that increases in waste levies had the second largest effect on decreases in coastal plastic pollution. Local governments are moving away from a collect and dump mindset to a sort and improve approach,” adds Hardesty.

Clean-up activities, such as Clean Up Australia Day, and surveillance programs that directly involved members of the community were also effective.

“Increasing community stewardship of the local environment and beaches has huge benefits. Not only does our coastline become cleaner, but people are more inclined to look out for bad behaviour, even using dumping hotlines to report illegal polluting activity,” says Hardesty.

Another piece of the solution to our plastics problem

This isn’t the be-all and end-all solution to Australia’s plastics problem – let alone globally – but this research does provide decision-makers with empirical evidence that the choices made by municipal waste managers and policymakers are linked to reductions in plastic pollution in the environment.

Identifying the most effective approaches for reducing coastal litter is an important part of future plastic pollution reduction strategies. The CSIRO’s Ending Plastic Waste Mission is aiming for an 80% reduction in plastic waste entering the Australian environment by 2030.

“While we still have a long way to go, and the technical challenges are enormous, these early results show that when we each play to our individual strengths, from community groups, industry, government and research organisations, and we take the field as Team Australia, then we can win,” says Dr Larry Marshall, chief executive of CSIRO.

Australia's coastal plastic pollution decreased by 29%

Credit: MarkPiovesan/Getty Images

Plastic pollution is an escalating global problem. Australia now produces 2.5 million tonnes of plastic waste each year, while world-wide production is expected to double by 2040.

This pollution doesn’t just accumulate on our beaches: it can be found on land and other marine environments (heard of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch?)

But according to a new study by Australia’s national science agency, CSIRO, plastic pollution on Australia’s coasts has decreased by 29% since 2013.

The study, which assessed waste reduction efforts in Australia and their effect on coastal pollution, highlights that although Australia’s plastic use has remained constant since 2013, local governments are getting better at preventing and cleaning up pollution.

“Our research set out to identify the local government approaches that have been most effective in reducing coastal plastics and identify the underlying behaviours that can lead to the greatest reduction in plastic pollution,” says lead researcher Dr Kathryn Willis, a recent PhD graduate from the University of Tasmania.

“Whilst plastic pollution is still a global crisis and we still have a long way to go, this research shows that decisions made on the ground, at local management levels, are crucial for the successful reduction of coastal plastic pollution,” she adds.

The study has been published in One Earth.

Local government approaches work

The new research builds upon extensive 2013 CSIRO coastal litter surveys with 563 new surveys and interviews with waste managers across 32 local governments around Australia completed in 2019.

The results found that, although there was a decrease in the overall national average coastal pollution by 29%, some surveyed municipalities showed an increase in local litter by up to 93%, while others decreased by up to 73%.

Since global plastic pollution is driven by waste reduction strategies at a local level (regardless of where the pollution originates), researchers then focused on identifying which local government approaches had the greatest effect on these levels of coastal pollution.

Get an update of science stories delivered straight to your inbox.

To do this they sorted local government waste management actions into three categories of human behaviour, including:

Planned behaviour – strategies like recycling guides, information and education programs, and voluntary clean-up initiatives.Crime prevention – waste management strategies like illegal dumping surveillance and beach cleaning by local governments.Economic – actions like kerb-side waste and recycling collection, hard waste collections and shopping bag bans.

Graphical abstract ofthe study. Credit: Willis et al (2022) DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oneear.2022.05.008

They found that retaining and maintaining efforts in economic waste management strategies had the largest effect on reducing coastal litter.

“For example, household collection services, where there are multiple waste and recycling streams, makes it easier for community members to separate and discard their waste appropriately,” says co-author Dr Denise Hardesty, a principal research scientist at CSIRO Oceans and Atmosphere.

“Our research showed that increases in waste levies had the second largest effect on decreases in coastal plastic pollution. Local governments are moving away from a collect and dump mindset to a sort and improve approach,” adds Hardesty.

Clean-up activities, such as Clean Up Australia Day, and surveillance programs that directly involved members of the community were also effective.

“Increasing community stewardship of the local environment and beaches has huge benefits. Not only does our coastline become cleaner, but people are more inclined to look out for bad behaviour, even using dumping hotlines to report illegal polluting activity,” says Hardesty.

Another piece of the solution to our plastics problem

This isn’t the be-all and end-all solution to Australia’s plastics problem – let alone globally – but this research does provide decision-makers with empirical evidence that the choices made by municipal waste managers and policymakers are linked to reductions in plastic pollution in the environment.

Identifying the most effective approaches for reducing coastal litter is an important part of future plastic pollution reduction strategies. The CSIRO’s Ending Plastic Waste Mission is aiming for an 80% reduction in plastic waste entering the Australian environment by 2030.

“While we still have a long way to go, and the technical challenges are enormous, these early results show that when we each play to our individual strengths, from community groups, industry, government and research organisations, and we take the field as Team Australia, then we can win,” says Dr Larry Marshall, chief executive of CSIRO.

US government to ban single-use plastic in national parks within a decade

US government to ban single-use plastic in national parks within a decade Biden officials make announcement on World Oceans Day in effort to stem huge tide of pollution from plastic bottles and packaging The Biden administration is to phase out single-use plastic products on US public lands, including the vast network of American national parks, …

Continue reading “US government to ban single-use plastic in national parks within a decade”

Carpet industry's recycling arm works against expanding mandates

Carpet is made mostly of plastic fibers derived from oil and accounts for about 1 percent of the U.S. waste stream, according to the EPA. The vast majority ends up in landfills or gets burned for energy. | Edwin Remsberg/Getty Images

A national nonprofit that runs state programs designed to promote recycling of used carpet is trying to prevent more of them from forming.

The industry-run group Carpet America Recovery Effort kicked two members off of its board earlier this spring for supporting New York and Illinois bills that would create recycling programs similar to California’s, which it helps run. The state proposals would put a tax on new carpets and distribute the proceeds to collection and recycling companies to turn discarded material into other marketable products.

Carpet recycling companies like the programs because they make recycling economic, but manufacturers argue that the extra fees — about 35 cents per yard in California — make their products less competitive with other types of flooring.

The episode illustrates the tensions that emerge when an industry group regulates itself. How large a role industry should play relative to regulators has been a sticking point as states try to enact extended producer responsibility laws for carpets, packaging and other products.

“CARE can’t come to terms with its own contradictions,” said Franco Rossi, president of Aquafil USA Inc., which recovers nylon from old carpets. Rossi was booted from CARE’s board in late April, along with the president of another recycling company. “The carpet industry runs the stewardship program in California because they have to, but they don’t want it anywhere else because they think it will hurt carpet sales.”

After recyclers advocated for the New York and Illinois bills, CARE leadership said they had violated the group’s conflict of interest policy. The group’s executive director, Bob Peoples, said in an email that states are best served by market-based solutions, “not by mandating unrealistic and arbitrary targets.”

Recycling supporters say the dust-up points to the need for more accountability and enforcement mechanisms in legislation that gives industry control over recycling.

“This is not just about carpet. When industries control recycling programs, and there aren’t enough guardrails, things can go very wrong,” said Heidi Sanborn, executive director of the National Stewardship Action Council, which advocates for legislation to require manufacturers to take responsibility for their products’ full lifecycles.

CARE was set up in 2002 as part of a partnership with the EPA, states and environmental groups. Its memorandum of understanding expired in 2012 and wasn’t renewed. The group also runs a voluntary, nationwide recycling program that includes a directory of collectors, recyclers and guidelines that it says have helped divert more than 5 billion pounds of carpet from landfills. But it stopped giving out industry-funded incentives in 2020, and recyclers say it’s not very active.

“For more than a decade, CARE has pretended they’re going to find a market-based solution,” said Louis Renbaum, president of DC Foam Recycle Inc., the other board member who was terminated. “But we’re dealing with a low-value product that has little chance of being recycled without subsidies.”

Carpet is made mostly of plastic fibers derived from oil and accounts for about 1 percent of the U.S. waste stream, according to the EPA. The vast majority ends up in landfills or gets burned for energy.

In California, carpet recycling rates are about 28 percent — far above the national average of 9 percent in 2018, the latest figure available. But the program’s performance has been uneven, with CARE paying more than $1 million in penalties for failing to improve rates from 2013-16. It again failed to meet its target of 24 percent in 2020.

CARE also required companies that accepted its incentives to refrain from supporting legislation that would require manufacturers to manage products’ lifecycles. Recipients of recycling funding had to attest that they would support “voluntary market-driven solutions” and not “legislation or regulations” creating extended producer responsibility requirements for 18 months after receiving funding, according to a copy of an agreement reviewed by POLITICO.

California regulators said they were worried about the group’s stance and what it means for carpet recycling. “I am very concerned about CARE’s ability to operate as a product stewardship organization if their main tenet is opposing EPR,” said Rachel Machi Wagoner, director of CalRecycle, the state’s waste management agency. “I don’t know what politics are happening within the organization, in terms of picking winners and losers, but their job is to build a circular system for carpet recycling.”

The carpet industry is also lobbying against the bills. The Carpet and Rug Institute, which has an overlapping membership with CARE, urged Illinois lawmakers to oppose the carpet-recycling proposal, arguing that it was “modeled on a problematic California program” and would create “an entirely new state bureaucracy.” CRI also pointed to CARE’s voluntary program as an alternative, arguing that it diverts carpets from landfills “without any additional taxation of consumers.”

CRI President Joe Yarbrough, who also serves on CARE’s board, said mandatory carpet stewardship legislation leads to a “death spiral”: The cost of carpet increases, which in turn slows sales, reducing how much carpet is ripped out of homes and commercial buildings to be recycled.

The Illinois bill failed to advance, but the New York bill has passed both houses; Gov. Kathy Hochul (D) could sign it later this year.

Adverts claiming plastic grass is eco-friendly are not allowed, says ASA

Adverts claiming plastic grass is eco-friendly are not allowed, says ASA Regulator upholds complaints that marketing by Evergreens UK Ltd was unsubstantiated and misleading Adverts claiming plastic grass is “eco-friendly” and “purifies” the atmosphere must be removed after the Advertising Standards Authority upheld complaints of greenwashing. The ASA upheld concerns that adverts claiming artificial grass …

Continue reading “Adverts claiming plastic grass is eco-friendly are not allowed, says ASA”

Microplastics found in freshly fallen Antarctic snow for first time

Microplastics found in freshly fallen Antarctic snow for first time New Zealand researchers identified tiny plastics, which can be toxic to plants and animals, in 19 snow samples Microplastics have been found in freshly fallen snow in Antarctica for the first time, which could accelerate snow and ice melting and pose a threat to the …

Continue reading “Microplastics found in freshly fallen Antarctic snow for first time”

Car tyres produce vastly more particle pollution than exhausts, tests show

Car tyres produce vastly more particle pollution than exhausts, tests showToxic particles from tyre wear almost 2,000 times worse than from exhausts as weight of cars increases Almost 2,000 times more particle pollution is produced by tyre wear than is pumped out of the exhausts of modern cars, tests have shown.The tyre particles pollute air, water and soil and contain a wide range of toxic organic compounds, including known carcinogens, the analysts say, suggesting tyre pollution could rapidly become a major issue for regulators.Air pollution causes millions of early deaths a year globally. The requirement for better filters has meant particle emissions from tailpipes in developed countries are now much lower in new cars, with those in Europe far below the legal limit. However, the increasing weight of cars means more particles are being thrown off by tyres as they wear on the road.The tests also revealed that tyres produce more than 1tn ultrafine particles for each kilometre driven, meaning particles smaller than 23 nanometres. These are also emitted from exhausts and are of special concern to health, as their size means they can enter organs via the bloodstream. Particles below 23nm are hard to measure and are not currently regulated in either the EU or US.“Tyres are rapidly eclipsing the tailpipe as a major source of emissions from vehicles,” said Nick Molden, at Emissions Analytics, the leading independent emissions testing company that did the research. “Tailpipes are now so clean for pollutants that, if you were starting out afresh, you wouldn’t even bother regulating them.”Tyres produce far more particles than exhausts in modern carsMolden said an initial estimate of tyre particle emissions prompted the new work. “We came to a bewildering amount of material being released into the environment – 300,000 tonnes of tyre rubber in the UK and US, just from cars and vans every year.”There are currently no regulations on the wear rate of tyres and little regulation on the chemicals they contain. Emissions Analytics has now determined the chemicals present in 250 different types of tyres, which are usually made from synthetic rubber, derived from crude oil. “There are hundreds and hundreds of chemicals, many of which are carcinogenic,” Molden said. “When you multiply it by the total wear rates, you get to some very staggering figures as to what’s being released.”The wear rate of different tyre brands varied substantially and the toxic chemical content varied even more, he said, showing low-cost changes were feasible to cut their environmental impact.“You could do a lot by eliminating the most toxic tyres,” he said. “It’s not about stopping people driving, or having to invent completely different new tyres. If you could eliminate the worst half, and maybe bring them in line with the best in class, you can make a massive difference. But at the moment, there’s no regulatory tool, there’s no surveillance.” The tests of tyre wear were done on 14 different brands using a Mercedes C-Class driven normally on the road, with some tested over their full lifetime. High-precision scales measured the weight lost by the tyres and a sampling system that collects particles behind the tyres while driving assessed the mass, number and size of particles, down to 6nm. The real-world exhaust emissions were measured across four petrol SUVs, the most popular new cars today, using models from 2019 and 2020.Used tyres produced 36 milligrams of particles each kilometre, 1,850 times higher than the 0.02 mg/km average from the exhausts. A very aggressive – though legal – driving style sent particle emissions soaring, to 5,760 mg/km.Far more small particles are produced by the tyres than large ones. This means that while the vast majority of the particles by number are small enough to become airborne and contribute to air pollution, these represent only 11% of the particles by weight. Nonetheless, tyres still produce hundreds of times more airborne particles by weight than the exhausts.Sign up to First Edition, our free daily newsletter – every weekday morning at 7am BSTThe average weight of all cars has been increasing. But there has been particular debate over whether battery electric vehicles (BEVs), which are heavier than conventional cars and can have greater wheel torque, may lead to more tyre particles being produced. Molden said it would depend on driving style, with gentle EV drivers producing fewer particles than fossil-fuelled cars driven badly, though on average he expected slightly higher tyre particles from BEVs.Dr James Tate, at the University of Leeds’ Institute for Transport Studies in the UK, said the tyre test results were credible. “But it is very important to note that BEVs are becoming lighter very fast,” he said. “By 2024-25 we expect BEVs and [fossil-fuelled] city cars will have comparable weights. Only high-end, large BEVs with high capacity batteries will weigh more.”Other recent research has suggested tyre particles are a major source of the microplastics polluting the oceans. A specific chemical used in tyres has been linked to salmon deaths in the US and California proposed a ban this month.“The US is more advanced in their thinking about [the impacts of tyre particles],” said Molden. “The European Union is behind the curve. Overall, it’s early days, but this could be a big issue.”TopicsPollutionRoad transportPlasticsAir pollutionMotoringnewsReuse this content