Walking from Mexico to Canada, I suppose, simply wasn’t tedious enough for me. So in late July, just as I reached the northern edge of California during a 2,653-mile thru-hike of the Pacific Crest Trail, I decided to start counting every single scrap of trash I created for an entire month. I carried it all for days on end in a disgusting Ziploc bag stuffed into my backpack—always gross, sometimes embarrassing, permanently revealing.

5 Rules to Reduce Waste on the Trail A thru-hiker’s best tips for decreasing your garbageRead More

For the first three months of my trek, I’d seen trashcans at almost every trailhead or convenience store my fellow Hiker Trash friends frequented, overflowing with our collective refuse. There were snapped trekking poles and overspent hiking shoes, empty pouches of dehydrated food and crumpled vestiges of instant coffee. The sheer quantity was impressive in a Mad Max prequel kind of way. How much stuff, I wondered, was I wasting?

So from Oregon’s enchanting Crater Lake to the faux Bavarian burg of Leavenworth, Washington, I catalogued every bit of my waste, chronicling each outgoing parcel in a single cellphone note that grew so long scanning it began to feel like a personal doomscroll. I trashed nine hummus containers and 30 Ziploc bags, two shoes and 34 cans of stove fuel, beer, and soda water. There were 17 ketchup packets, almost as much hot sauce, and one plastic pint of Southern Comfort. I discarded so many compostable coffee pouches that I could not compost that I now cannot bear to type the number.

On and on it went, from pizza boxes to joint containers, red pepper pouches to two garlic bulbs. By the start of September, I’d somehow discarded 686 separate items, or more than 20 each day. And those were only the ones I remembered to count during a month when I tried to curb my waste. That was less than a quarter of my hike, meaning I’d likely tossed an excess of 3,000 bits of junk overall, more than one per mile. I reached the Canadian border a week later, toting more than a twinge of guilt.

If we hikers, who live outdoors and ostensibly for it, aren’t obsessive stewards of shared resources, how can we expect anyone else to be? We must do better.

Like much of the outdoors industry, hiking has a waste problem. In our dauntless quests to achieve ultralight enlightenment, make four-day food carries less burdensome, or have the latest gear with the most Reddit cred, we have created a slash-and-burn superstructure, where the fulfillment of our goals or ideals trumps their environmental impacts. We purchase the tiniest portions of food. We bail on gear that isn’t perfect or, back home, stockpile things we never again need. We buy more than our bellies can handle in trail towns, gorging until we toss what remains. I confess to it all.

Much of this happens for the sake of convenience, for making a difficult endeavor that much easier. Some of it stems from a deference to apathy, since, as we often shrug, our footprint is so much smaller in the woods than when we’re back in “the real world.”

But if we hikers, who live outdoors and ostensibly for it, aren’t obsessive stewards of shared resources, how can we expect anyone else to be? We must do better. Good news: with a little inconvenience, expense, and planning, we can.

In the waning days of my experiment, I was delighted to learn about another PCT hiker who was paying even more attention to her trash—or, really, her near-complete lack of it. In mid-April, Ana Lucía departed the trail’s southern end, bound north with an unprecedented mission: to hike to Canada without generating any refuse. “Waste-Free PCT,” she dubbed it.

“For me, waste-free means trying not to have a lot going into landfills,” Lucía said in mid-September, less than a month before she reached the trail’s northern terminus. “It’s impossible to be 100 percent waste-free if you’re on a trail, but it’s about being more mindful of the trash you are producing and asking, ‘What can I do better?’”

A 26-year-old native of Mexico City, Lucía fell for hiking and environmental causes in tandem half a decade ago. After learning about the exploitation involved in unsustainable tropical palm oil production, she began changing her habits as a consumer. Vegetarianism and veganism soon followed, as did stints at animal-rehabilitation centers. After reading about “Plastic Free July,” a decade-old international movement involving a month-long pause on plastic, she decided to curb her overall waste dramatically, too.

Meanwhile, Lucía daydreamed about the PCT since she first saw Reese Witherspoon lug her overstuffed bag to the Bridge of the Gods at the end of Wild, soon after the movie’s 2014 release. For years, earning her psychology degree at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México and a subsequent teaching stint put that ambition on hold. She decided to make her attempt at last in 2021, before beginning a doctorate program in neuroscience.

Ana Lucía in search of a composting coffee shop (Photo: Lucía)

Another obstacle appeared. She couldn’t find anyone who had documented such a waste-free long haul, let alone explained its pragmatic complications. On message boards and blogs, fellow hikers scoffed at the notion—too much work, they concurred, in a world that would go on making waste with or without her. Lucía was torn between hiking the PCT and trying to remain as waste-free as she had learned to become at home. “It felt like doing this dream meant having to renounce my values,” she said.

Rather than give up, she dug in, shaping schemes that would let her pursue both goals. She found a family friend in California who was willing to buy trail mix, peas, and gummy bears in bulk for six months and mail them to isolated trail towns. He even used compostable BioBags and paper tape. She emailed niche brands like Gossamer Gear and Katabatic to inquire about used packs and quilts they could sell her to assist the mission. (Both said yes.) She scoured Reddit boards in search of secondhand supplies, insisting on buying as little new as possible; when she couldn’t find the exact model she wanted, she settled for her second choice.

To offset the expenses of these impracticalities, she also launched a crowdfunding campaign, pledging 26 percent—that is, one percent for every 100 miles she intended to hike—of it to the Mexican Center for Environmental Law. “I wanted to balance out the impact of doing the trail and shipping these boxes by giving,” said Lucía. She ultimately raised more than $4,000.

Lucía couldn’t hike on bulk trail mixes alone. Same as other hikers, she wanted energy bars and dehydrated meals, simply housed in compostable packaging. She found one supplier for each: LivBar, a solar-powered vegan bar maker in Salem, Oregon, and Fernweh Food, a tiny startup in Portland, Oregon, that might just be making the best dehydrated meals on the market right now.

She hauled her used wrappers into trail towns, found coffee shops that composted their grounds, and asked if they would do the same for her packaging. In Northern California, where towns with coffee shops are either limited or very far from trail, she mailed her wrappers to Fernweh founder Ashley Lance back in Portland, reckoning the energy spent doing so meant less waste than throwing them away. Lance composted them in her backyard, then offered the same service to other hikers.

“If you were a guest in your friend’s house, you wouldn’t leave your trash everywhere. Taking care of the trail and making less waste is like paying rent.”

Both Lance and LivBar CEO Wade Brooks admitted to me that the battle to make compostable wrappers common is an uphill one. Brooks, for instance, repeatedly raved about a new machine that would allow LivBar to package its goods with less labor, eventually lowering the price point to be more competitive with the plastic-clad likes of Kind or Clif. Fernweh spends more than a dollar on every meal’s compostable label and wrapper. Despite a price point between $9.50 and $15, Lance still earns only 10 cents per bag.

But they both sensed a mutual momentum, a feeling that the behemoths were paying attention. “Small companies make a change, and big companies see that people are choosing them,” Lance said. “Those companies eventually acquire those habits in their own way.”

Lucía hoped her own journey would inspire similar shifts among hikers. Now that someone had done the work of figuring it out, she suggested, others could more easily follow. Future thru-hikers have already told her she altered the way they will plan their walks. She wondered if trail towns or the Pacific Crest Trail Association might someday install roadside compost or recycling stations.

“Nature is free. It’s not asking anything of you,” said Lucía, who rightly adopted the trail name “Eco” on the PCT. “If you were a guest in your friend’s house, you wouldn’t leave your trash everywhere. Taking care of the trail and making less waste is like paying rent.”

I am neither naïve nor conceited enough to think that hikers eating out of compostable wrappers or frequenting gear exchanges more often will make an appreciable difference in our ballooning environmental calamity. Among our society’s possible causes of death, the inability to find a composting center in some trail town of Southern Appalachia won’t rank at all.

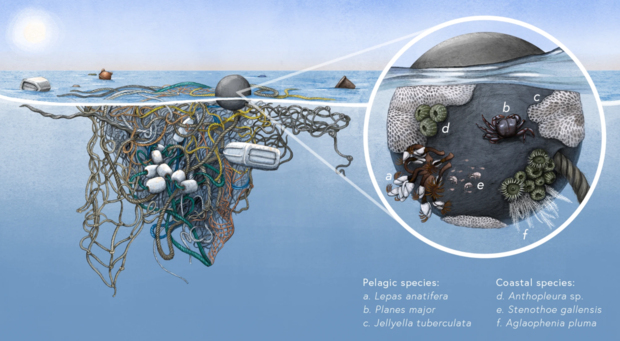

Meanwhile, the picture just gets grimmer: A 2020 study published in Science estimated that the world dropped 5.3 million metric tons of plastic into the ocean in 2016, a number that could increase nearly sixfold in just two decades. The political ambitions of 52 U.S. Senators seem again poised to cripple long-overdue climate reform, even after the United Nations gathered again to fret over our folly. And Saudi Arabia now intends to convert an expired oil rig into an “extreme park,” a seabound monument to our collective ostrich effect.

Why should you care about tampons or toilet paper in the woods or how much plastic you route to landfills when that’s happening? Or when pipelines crisscross the Appalachian Trail and interstate systems, our country’s collective arteries of disposable goods, cleave the Pacific Crest Trail in pieces? I get it.

But in his rambling autobiography, Theodore Roosevelt—the problematic godhead of our public lands, with all their blessings and faults—gets to the essence of why this all matters, even when it’s frustrating or inconvenient or expensive. “The greatest happiness is the happiness that comes as a by-product of striving to do what must be done, even though sorrow is met in the doing,” he writes. He goes on to quote a friend who ran a mill just north of Damascus, Virginia, arguably the epicenter of Appalachian Trail culture for its legendary hiker hostels and annual Trail Days celebration: “Do what you can, with what you’ve got, where you are.”

I choose Roosevelt’s advice. I will find ways to reduce my environmental impact while on trail, though I know my efforts will cost me and will amount to less than a candle’s flicker in a consumerist gale.

I will mail myself bits of bulk toiletries. I will use Ziplocs or BioBags not until they look like a septic tank but instead until the seams split. I will lug a little extra food weight from one stop to the next if it means using a little less plastic and, gradually, reducing what I toss. And I will buy, as best I can, products from manufacturers that agree they can’t change everything but are at least, per Roosevelt, “striving to do what must be done.”

None of this will be perfect. But when I count my trash and scraps on the next trail, I want to feel empowered by what I have fixed, not embarrassed by what I ignored simply for the sake of convenience.