The first pull of the day was a Corona bottle, its label scraped off by the coarse sand just off the shore of South Lake Tahoe. How long it had been there was anyone’s guess.

A freediver in the floating cleanup crew unearthed it from the sand — only about 12 feet deep here — and surfaced to dump it in a green floating trash raft named Darlene.

“Partyyyy! Wooo!” shouted Colin West, amused and sarcastic. “I bet that isn’t the last beer bottle we find today.”

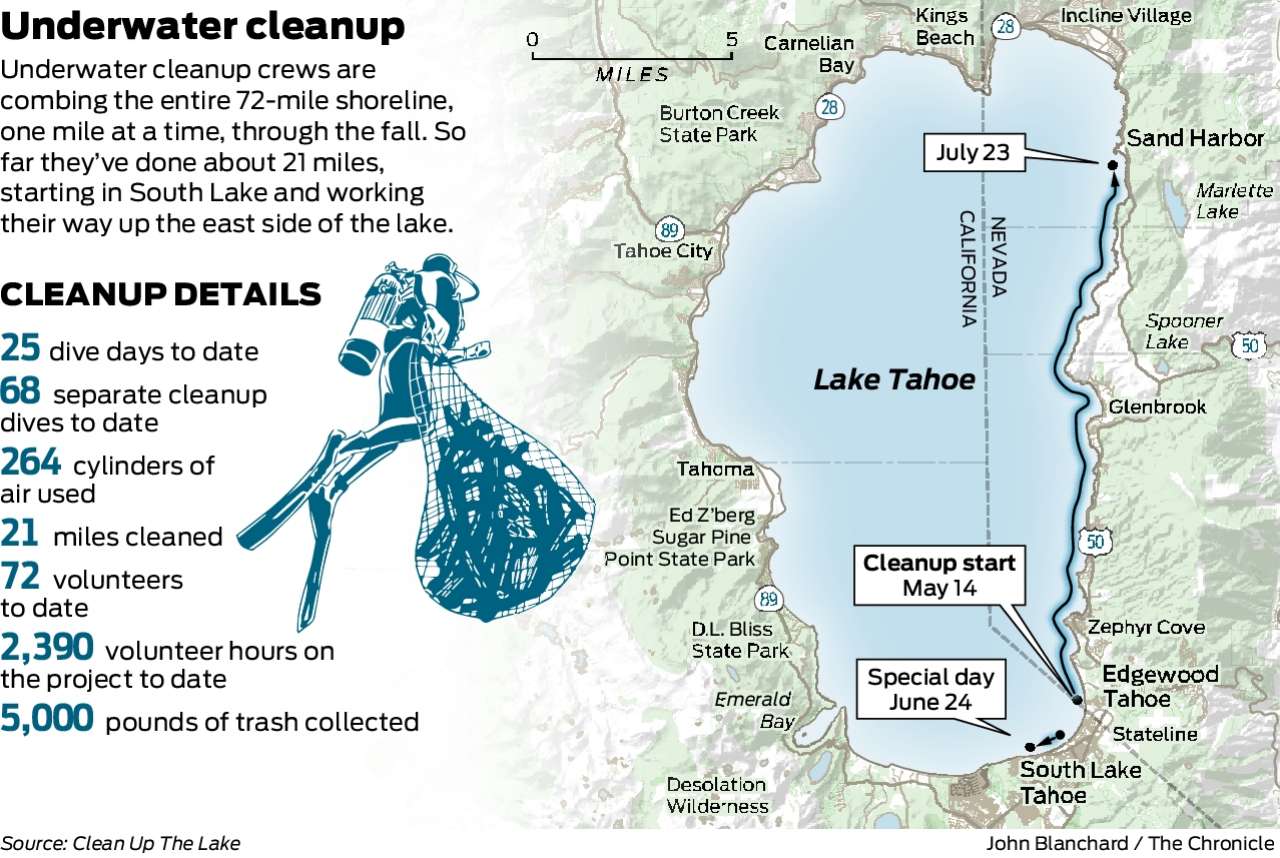

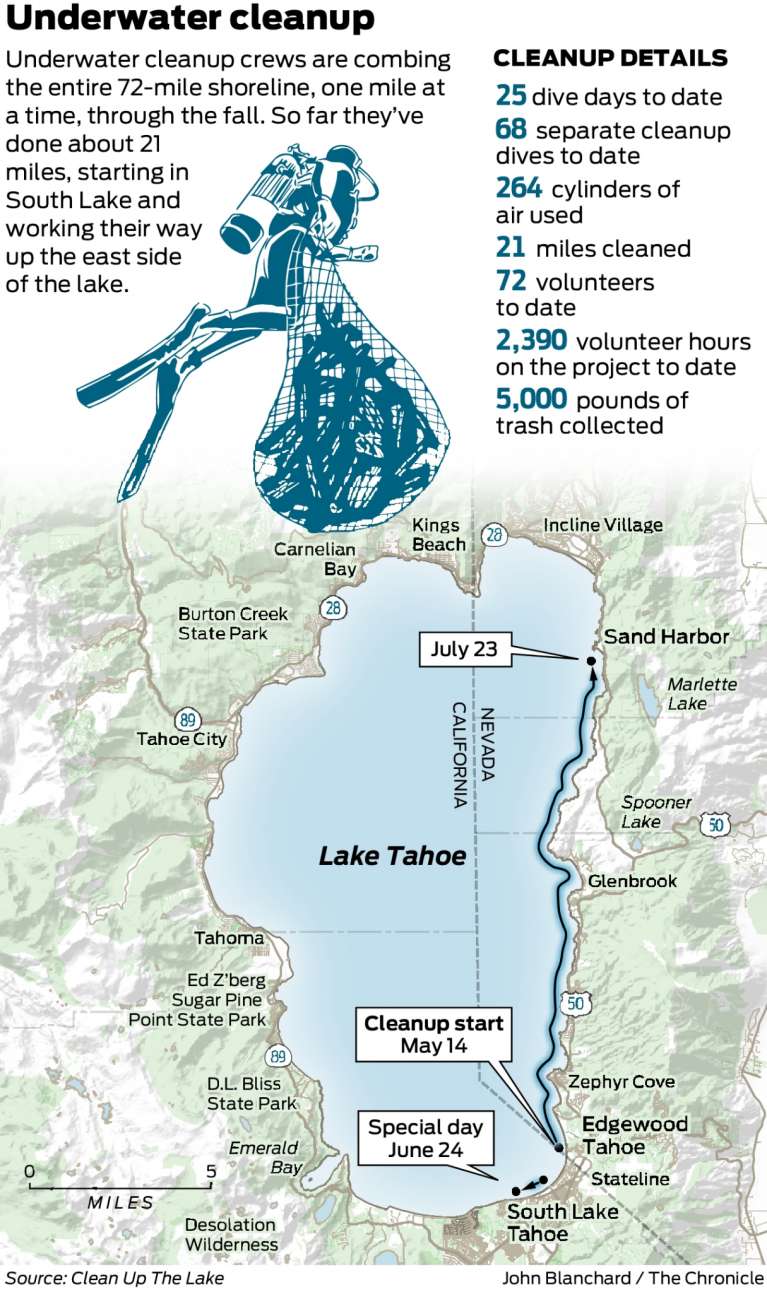

It was Day 15 of the first-ever effort to systematically scoop up submerged litter and junk that has accumulated on the bottom along Lake Tahoe’s 72-mile shoreline. Fluffy clouds hovered above the south shore’s shallow crescent and summer heat warmed up the alpine basin.

Fifteen people, most of them volunteers, had gathered at the Ski Run Marina earlier that morning and loaded three motorboats, three yellow kayaks, one Jet Ski and Darlene with dive gear and snacks in preparation for a long day on the water. Then everyone motored out to a spot a stone’s throw from the Nevada border and the divers hopped in the water.

Divers move a large piece of debris from the bottom of Lake Tahoe to a raft as they collect trash from under the water.

Nina Riggio/The Chronicle

From now through the fall, West, 34, of Stateline, Nev., will be leading these roving teams of divers and boaters through his nonprofit, Clean Up the Lake, which he founded three years ago to conduct coordinated beach and underwater trash pickups.

He said he would love to scour the entire lake bed, but Tahoe is deep and craggy, plunging 1,645 feet into the Earth at its lowest point. The deepest a recreational scuba diver can go safely is about 100 feet, but descending past 25 feet at the High Sierra altitude increases the risks of decompression sickness, so that’s about as far down as West’s crews will go.

“We’ve done 12 miles of the Nevada side. Now I’m excited to see how much trash is in California,” West said.

By extracting thousands of pounds of garbage from the sapphire-blue lake, the project speaks to Tahoe lovers who may worry about the lake’s health. The historically clear water has grown relatively murky with sediment and algae in the past decade, a development tied to warmer water temperatures caused by climate change. Invasive weeds and invertebrates are changing the composition of the lake as well.

Combing the entire near-shore environment is an unprecedented act of stewardship. West’s project will provide the first clear look at a mess that has been building since Tahoe’s development explosion in the 1950s, a time when boaters casually tossed empty beer cans and busted fishing gear overboard.

So far, his crew has covered 21 miles and collected more than 5,000 pounds of trash, ranging from the mundane (glass bottles and sunglasses) to the obscure (sex toys, a 1980s-era boom box) to the intentional (abandoned car tires).

I accompanied West’s crew on a cleanup dive in June as a trash-collecting scuba volunteer. Moments before our descent, West warned our group about encountering problematic items underwater.

“If you find anything — let’s say, criminally related — like a gun or a body part, signal to me,” West said. “We have a whole thing we do to let law enforcement know, and then they come out and take care of it.”

On that alarming note, we descended to the sandy bottom and started hunting for trash.

Now Playing:

West is tall and broad-shouldered, with a close-cropped blond beard and a fondness for Teva sandals. He’s a filmmaker and television showrunner by trade and organized his nonprofit in 2018 to clean beaches in Belize. But he quickly shifted its focus to Tahoe after hearing about litter buildups in the lake.

The first major Tahoe underwater cleanup took place that same year at Bonsai Rock, a popular summer hangout on the rugged eastern shore marked by clusters of giant, egg-shaped granite boulders poking out of the water. In one day, locals pulled out 600 pounds of litter, including hundreds of beer cans.

“That was when it became obvious that this was a problem,” said Matt Levitt, founder and CEO of local distillery Tahoe Blue Vodka, who volunteered at Bonsai Rock and is sponsoring West’s project. “It had been 50 years of people using this lake as a trash can before the whole eco-conservation movement got legs.”

Since settling in Tahoe, West has happily, obsessively taken on the role of underwater garbage man. He keeps a crate in the bed of his pickup truck for litter he casually picks up running errands. There’s a garbage can in his backyard full of tangled fishing line and lures. He hasn’t bought a pair of sunglasses in four years — the lake is full of free ones.

“The more I dove and the more I researched, the more I saw the problem, and the bigger my plans became,” he said. “I’ve seen Belize, I’ve seen Bali and other places that feel like they’re so far gone already with how bad the trash is. Tahoe feels like it’s still within grasp.”

He couldn’t have picked a better time for this endeavor.

Since the onset of the coronavirus pandemic, Tahoe has become a haven for remote workers decamping from the Bay Area and a greater attraction to millions of road-tripping tourists. With more bodies and cars moving through the precious alpine environment, locals are more concerned than ever about how to guard against long-term damages.

“As more and more people come, it’s getting harder and harder to reverse the impact they’re having,” said Jesse Patterson, chief strategy officer for the League to Save Lake Tahoe, the cleanup and conservation nonprofit behind the “Keep Tahoe Blue” campaign. “It’s been several decades of stuff getting into the lake, and we need to take it out and start fresh.”

Volunteer diver Hayden Farris, left, helps Colin West, founder of the nonprofit Clean Up the Lake, move scuba tanks to a raft. The group, which scours the subaquatic environment for trash and debris, hopes to cover all 72 miles of shoreline by this fall.

Nina Riggio/The Chronicle

No one knows exactly how much garbage is in the lake, but Seth Jones, of South Lake Tahoe, probably has the clearest view of the issue. He performs invasive species control in the lake professionally — scuba diving to exterminate Asian clams in Emerald Bay, for example — and has been quietly moonlighting as a subaquatic trash collector since 2012.

Jones and his dive buddies have hauled out tens of thousands of pounds of trash. Last year, he and his dive partner, Monique Rydel Fortner, formed the nonprofit Below the Blue to formalize their efforts.

“There’s so much stuff out there, it’s mind-boggling,” Jones said.

Beyond the litter is a deeper issue of commercial-industrial dumping, he said. Engine blocks and tires. Construction debris. Commercial fireworks canisters. Sunken boats that get pulverized into thousands of pieces.

“They just get ground to a pulp over the years,” Jones said. “No agency dives for that kind of stuff. Everyone knows it’s a problem, but it’s not anyone’s jurisdiction.”

Boats that sink in Tahoe are often left there. Occasionally, authorities will commission a local salvage company (or sometimes Jones) to retrieve a craft’s engine, battery, gas and sewage tanks — the parts that leach toxins and pollutants into the water.

Jones’ dream is to marshal a full-scale trash excavation of the lake with side-scan sonar sweeps, deep divers, remote-operated submersibles, barges with cranes and winches — the works. But that would cost tens of millions of dollars.

Removing trash from the near-shore areas — West’s goal — is the place to start, Jones reckons.

Clean Up the Lake captured the public imagination as soon as it was announced in the spring. A fundraising goal of $100,000 was hit within a week; Levitt matched the total. Several more donors chipped in to fully fund the quarter-million-dollar project.

“It’s one of the most successful projects we’ve ever done,” said Allen Biaggi, board chair of the Tahoe Fund, an environmental nonprofit that oversaw the fundraising campaign. “It really resonated with people. This is just the right thing to do for Tahoe right now.”

Volunteer Luba Guvernator jumps in for her third and final dive of the day to collect debris from the bottom of Lake Tahoe on Tuesday, July 6, 2021.

Nina Riggio/The Chronicle

On the day I dived with the cleanup crew, the water off South Lake was swimming-pool clear and mellow. The bottom was flat and sandy, though lousy with the white, dime-size half-shells of dead invasive Asian clams.

After more than 200 dives, West has these operations down to a science.

Four scuba divers comb the terrain, scooping trash into yellow mesh handbags. From the surface, two free divers (no air tanks) wearing fins and snorkels follow along, occasionally swooping down to ferry full trash bags up to Darlene the trash raft.

When a scuba diver finds a cumbersome object — say, an old tire — they signal for assistance, and a free diver brings down a rope attached to a kayak above. Together, they’ll muscle the thing out of the water. For larger or especially heavy junk items, West will mark the GPS location. He hopes to return next year with a crane to haul them out.

The first thing I found was an artisanal clear glass jar, partially buried in the sand. Then a brown hand grenade-shaped beer bottle. Then a 30-foot length of white twine. A strand of electrical wiring. Piece of a broken fishing rod. Length of aluminum pipe. Rimless reading glasses slippery with algae growth.

It felt like a treasure hunt and lasted about an hour. Each of the four divers filled about three bags. By the end of the day, the group had brought up 318 pounds of junk.

One caveat to the cleanup: Any objects that appear to be older than 50 years could carry historical significance and must be left alone — even something as obviously out of place as a rusted tin can. West notes their location and will take his findings to the state when the project wraps.

Divers haul up litter found on the bottom of Lake Tahoe. From now through the fall, volunteers will conduct coordinated underwater trash pickups along all 72 miles of the lake’s shoreline.

Nina Riggio/The Chronicle

The diving gets all the attention, but the trash-sorting is just as important.

Every item is dried, weighed, photographed and logged — there are 77 categories, based on a labeling system designed by the United Nations for underwater materials. Then it is either recycled, stashed for future public art projects or disposed of properly.

By converting the trash into data points, the project will help researchers and conservation nonprofits understand not only what’s in the lake but also where it comes from and where it accumulates in the subaquatic landscape. As microplastics have filtered into the lake, West’s team is providing samples to experts for further research.

It’s worth questioning whether pulling litter out of Tahoe will meaningfully improve the health of the environment. Most of what West’s crew finds probably isn’t leaching high concentrations of heavy metals or chemical pollutants into the water.

“There are things in there that are potentially bad, but given the size of Tahoe, the real negative impact of those things is probably negligible — or not measurable,” said Geoffrey Schladow, who directs the Tahoe Environmental Research Center at UC Davis. “Having said that, this project is great for building awareness.”

First the beach pickups, now the near-shore project, maybe one day the deep clean. The assumption is that we have evolved past chucking beer bottles overboard, that most of the things West’s crew pulls out will not go back in.

“We’re definitely making progress,” he said. “Sometimes, that starts with correcting the mistakes of the past.”

Gregory Thomas is The Chronicle’s editor of lifestyle & outdoors. Email: gthomas@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @GregRThomas