Editor’s note: This is the third entry in a series examining the causes, impacts and solutions to plastic pollution in the Great Lakes. Read the first and second stories here.

Thirsty? Would you like a little plastic with your drinking water?

That may sound ridiculous, but researchers say it has, unfortunately, become a serious problem that bears further study as evidence mounts that people are eating, drinking and inhaling microscopic pieces of plastic on a regular basis.

In Michigan, water utility managers say microplastic contamination is matter of emerging concern, but the problem ranks lower on the priorities list because research into the overall ubiquity and health implications of such contamination is in its infancy.

The story is similar for microplastics in food — particularly in fish harvested from the Great Lakes, which are, sadly, awash in plastic fragments. The smallest pieces are entering the base of the food web and showing up in fish guts. But how those tiny particles are affecting the health of animals and potentially the humans that eat them isn’t well understood.

“We’re breathing this stuff in, too,” said Sherri Mason, sustainability coordinator at Penn State Behrend who studies microplastic in the Great Lakes.

Ever since Mason began speaking in public about plastic pollution, the question of how the manmade material is affecting humans has been frequently asked.

“That is always where it leads to,” Mason said. “It’s frustrating that we don’t have all the answers. But the data we have right now is not (encouraging).”

When it comes to plastic in tap water, all eyes are on California as the most populous U.S. state develops regulatory guidelines for microplastics in drinking water. The state’s Water Resources Control Board is expected this year to issue a preliminary safety threshold for the microscopic particles, which are defined as three-dimensional in shape and less than five millimeters long.

The effort is complicated by the lack of standardized test methods for microplastics in drinking water and a relative scarcity of research on their ubiquity and health impacts. But researchers say it’s an important precautionary step that’s probably overdue.

“We now know that we live in a soup of plastic that is getting ever denser. And we don’t seem to be changing our ways. And the contaminants, they live longer than we do, meaning that the soup will get thicker,” Rolf Halden, director of the Biodesign Center for Environmental Health Engineering at Arizona State University, told the nonprofit news site CalMatters.

“So, is it too early to do something? No, it is actually a bit late.”

In the Great Lakes region, Mason co-led a 2018 study that found microplastic fibers in 159 samples of tap water from around the world, including 12 brands of beer brewed with Great Lakes source water and 12 commercial sea salt brands.

Most of the plastics in the water samples were tiny fibers, which are suspected to have come from the air. That makes it a difficult problem for utilities to control.

“As soon as your water comes into contact with air, that’s got microplastics in it,” Mason said. “I think utilities feel like there’s nothing they can do.”

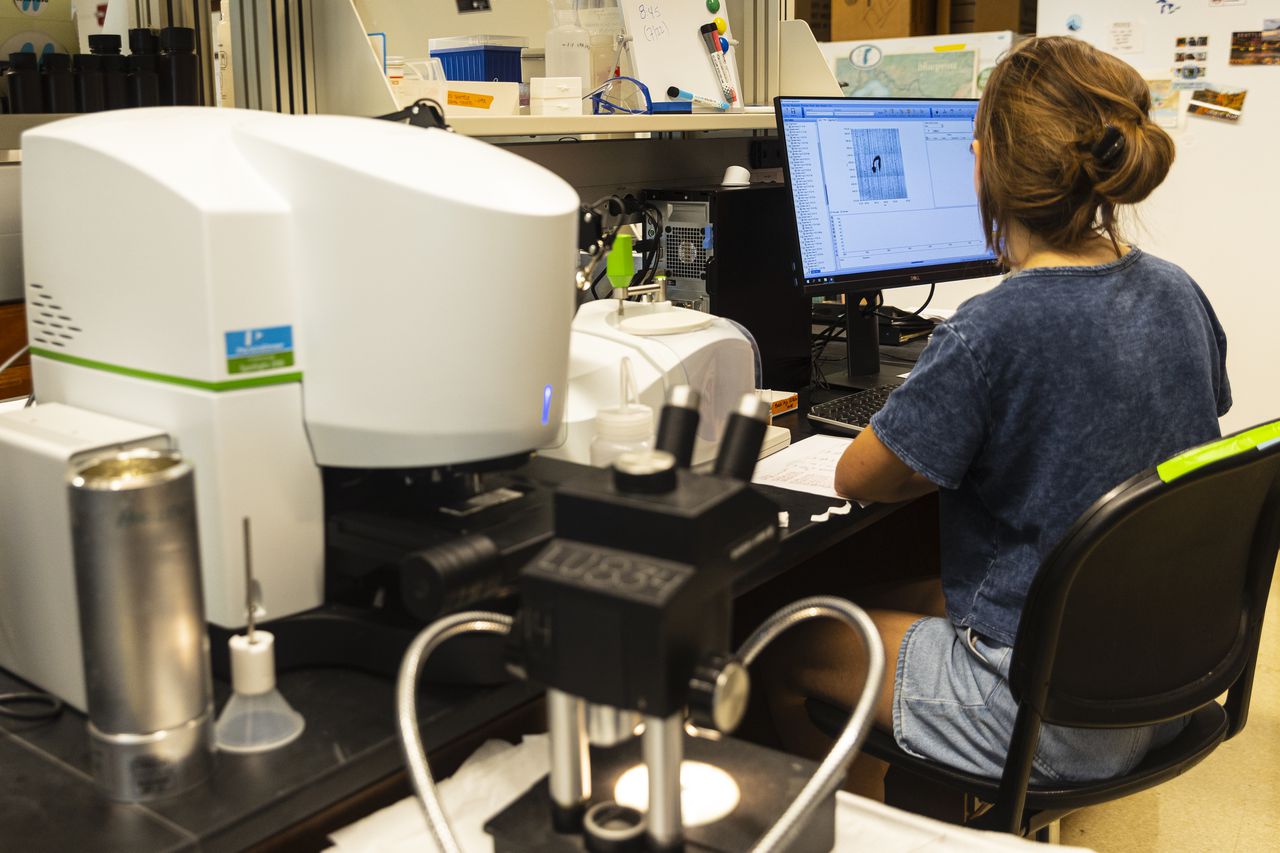

A Loyola University Chicago student exams micro plastic with a microscope at an environmental research lab at Loyola in Chicago, Ill. on Thursday, July 22, 2021. (Joel Bissell | MLive.com)Joel Bissell | MLive.com

Utility managers discuss microplastics at conferences, but “I can’t say that utilities are particularly focused on it,” said Bonnifer Ballard, director of the Michigan Section of the American Water Works Association, a trade group that represents municipal water utilities. “It’s clearly getting through the system, but I don’t think its pervasive, so it doesn’t rise to the top in terms of concerns.”

The longevity of plastic — which can last for hundreds of years, breaking down into smaller pieces as time goes by — is a major concern for Myron Erickson, public utilities director for the city of Wyoming, which draws its water from Lake Michigan.

But Erickson is less concerned about people consuming microplastic through municipal water systems because conventional treatments that process surface water from lakes and rivers are meant to remove solid particles. Once the water percolates through a filter bed, Erickson said it doesn’t see the light of day again until it comes out someone’s tap.

“It’s a closed, pressurized system by design. There really isn’t a way for it to become contaminated,” he said. “That’s not to say it’s impossible, but that’s not where I’m worried when I think microplastics. I’m worried about the oceans, the air we’re breathing and the fact that there isn’t ever going to be a Flint or a Belmont of microplastics to bring it to population’s attention. The Belmont and Flint of microplastic is Planet Earth.”

But evidence suggests that some plastic is coming out of the tap. The 2018 study which found microplastic in tap water samples from around the globe included 33 samples from the United States with an overall average of more than nine plastic particles per sample. Researchers in the effort took precautions to avoid potential airborne fiber contamination.

Tap water from Holland, Alpena, Chicago, Milwaukee, Duluth, Buffalo and Clayton, N.Y., all contained at least one microplastic fiber. Each of those utilities draws water from a Great Lakes intake. But beer brewed with that water contained more particles overall, leading study authors to conclude the results “indicate that any contamination within the beer is not just from the water used to brew the beer itself.”

“That’s almost certainly coming from employees and humans making and handling and bottling the beer,” said Erickson. “Drinking water doesn’t really work that way.”

Bottled water — typically packaged in single-use plastic bottles and generally subject to less regulatory oversight than public utilities — appears to contain more plastic on average than tap samples, according to another 2018 study led by Mason. Analysis of nearly all major bottled brands sourced from around the world found an average of 10 particles per liter. Water bottled in glass had lower particle counts and authors wrote that “data suggests the contamination is at least partially coming from the packaging and/or the bottling process itself.”

When it comes to the Great Lakes, another major point of concern for human ingestion of plastic is through contaminated fish. Microplastic fibers are showing up in high quantities in fish guts, but the question researchers are still driving toward is whether those particles are being absorbed into fish tissue that people would consume.

A dead cormorant, a type of diving bird, is bird is tangled up in plastic balloon ribbon at the Elberta, Mich. beach pier on Lake Michigan, Aug. 14, 2021. Balloon debris is among the 22 million pounds of plastic estimated to enter the Great Lakes each year. (Garret Ellison | MLive)Garret Ellison | MLive

What is abundantly clear is that rivers are bringing plastics from various sources to the Great Lakes and, along the way, fish in those rivers are eating them. In 2016 and 2017, Loyola University Chicago biologists sampled 74 fish from the Muskegon and St. Joseph rivers in Michigan and the Milwaukee River in Wisconsin. They found that 85 percent had microplastics in their digestive tract, with an average of 13 particles per fish.

Canadian researchers published a study this year which found a record 915 particles in the digestive tract of a Lake Ontario brown bullhead. High particle counts were found in other fish, including white suckers from Humber Bay and Toronto Harbor, which had more than 500 particles apiece. A longnose sucker from Lake Superior’s Mountain Bay had 790 particles. In the Humber River, up to 68 particles were found in common shiner minnows.

“Microplastic is interacting with aquatic wildlife,” said Rachel McNeish, a post doc researcher on the Loyola study. “Fish are consuming it — either actively eating it thinking its food, eating insects with microplastic in them or maybe just drinking water with microplastic. Or they may consume it through contact with sediment. In any case, microplastic is entering the food web.”

Does that mean fish which ate plastic pose a health risk to humans?

John Scott, a chemist at the Illinois Sustainability Technology Center (ISTC) who studies microplastics, said particles in the lakes are known to absorb and concentrate contaminants such as PCBs, PFAS, DDT, flame retardants and other toxic chemicals. When it comes to chemicals, the question is whether or not the plastics eaten by fish amplify biomagnification of contaminants up the food chain. In other words, are they making larger fish more unsafe to consume than they otherwise would be?

In 2018, researchers suspended plastic nurdle pellets in Muskegon Lake for three months. After one month, they found pollutants like PFAS, PCBs and PAHs had concentrated in a biofilm that developed on the pellets at levels hundreds of times higher than background levels.

“There is that potential for magnification,” said Alan Steinman, a Grand Valley State University researcher who led the study — which led to more questions. “If it’s taken up by an organism, we don’t know if it will be further biomagnified and have a negative impact.”

Scott, who was co-author on the Muskegon Lake study, said chemical additives in plastic — which is primarily made using fossil fuels — are also a concern. “There’s thousands of these additives in plastic and not at trivial levels,” he said.

To cross biological membranes and not be simply expelled by the body as waste, plastic particles would have to break down to nanoplastic levels. Research on the toxic effects of plastic on humans micro and nano levels is still in its infancy, but some studies have indicate the potential for serious problems. A 2021 scientific review in the journal Nanomaterials noted that researchers have already been able to demonstrate the microscopic particles are “able to cause serious impacts on the human body, including physical stress and damage, apoptosis, necrosis, inflammation, oxidative stress and immune responses.”

“Everyone is talking about microplastic, but down the road, I think that might shift to nano or even pico plastics,” Scott said. “Those things are more liable to get into the body and stay there.”

Related stories:

Great Lakes plastic pollution is only getting worse

Industrial plastic pellets litter Great Lakes beaches

Zeeland plastic powder spill sparks evacuations

Microplastic fibers prevalent in Great Lakes tributaries

Ann Arbor eyes ban on single-use plastics