They are in the water we drink, the packaging of the food we eat, the utensils we cook with, the beds we sleep in, the clothes we wear and even within our own bodies. There is no escaping so-called “forever chemicals”, a set of long-lasting and potentially harmful human-made substances that infuse almost every environment on the planet.

The US government is now proposing its first-ever restrictions on six of these chemicals, known as per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) says the restrictions could, over time, prevent thousands of deaths, if they are implemented. The European Commission is also preparing to ban a set of PFAS compounds in fire-fighting foams.

Some companies have already begun phasing out the most closely-studied PFAS chemicals – PFOS and PFOA. These are hazardous to the human immune system, and have been linked to negative effects on fertility, childhood development and metabolism.

But there are more than 9,000 PFAS compounds, which have hundreds of different uses, including in non-stick coatings, fabric protectors, and plastics. And some, including PFOS and PFOA, can persist in the environment for decades.

How long do forever chemicals actually last?

This long list of chemicals earned their nickname for a reason – they are persistent. They not only survive for a very long time without breaking down, they have the worrying ability to accumulate within living organisms. This means that even low levels of exposure can gradually build over time to a point where they become harmful.

Their persistence depends on the molecular structure and make-up of the individual substances. Not all of these infamous chemicals are equal.

All PFAS compounds have a backbone built of carbon – those with fewer than six carbon atoms are “short-chained”, while the rest are “long-chained”. Long-chain PFAS compounds may remain in the body for far longer than short-chain ones, according to one small study of workers at Arvidsjaur airport in northern Sweden. They had been drinking water containing PFAS compounds from firefighting foams, following an accident. Their blood samples contained long-chained PFOS with a half-life of 2.93 years, and PFOA with a half-life of 1.77 years. A short molecule called PFBS, by contrast, had a half-life of just 44 days. One reason for this is that the kidneys seem to be better at eliminating the short chain molecules from the body.

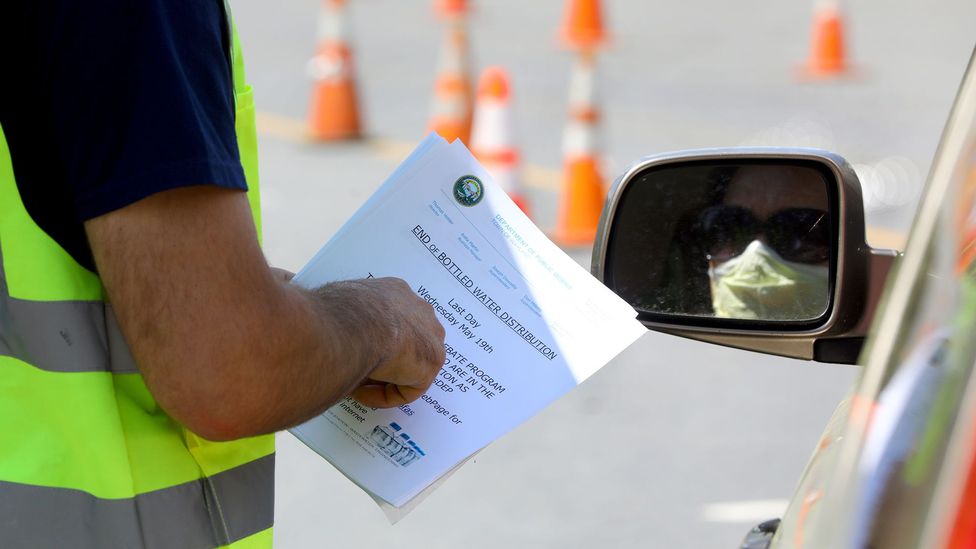

Elevated levels of PFAS in public water supplies can mean residents need to drink bottled water instead of from the tap (Credit: Pat Greenhouse/The Boston Globe/Getty Images)

It’s worth remembering that the half-life doesn’t mean the chemical is eliminated in that time. Rather it is the time it takes for the levels in the blood to fall to half their original value. The chemicals can remain in the body for far longer, especially if continually topped by drinking contaminated water or other sources.

You might also like:

Another study of a far longer-term exposure to PFAS among people living in Ronneby, southern Sweden, found that the half-life for another chemical called PFHxS was 5.3 years, while PFOS was 3.4 years and PFOA was 2.7 years. Some PFOS compounds that contain additional branches from their main carbon backbone have a half-life that stretch into decades within the human body.

In water, however, they can linger even longer. Some studies have suggested that PFOA has a half-life of more than 90 years, while for PFOS it is more than 41 years.

Read more about the chemicals that can linger in our blood for decades in this piece by environmental journalist Anna Turns.

Where do forever chemicals come from?

Some of the most commonly reported sources of PFAS contamination is from the use of fire-fighting foams, particularly in those for extinguishing flammable liquid blazes. Here the PFAS act as “surfactants”, to decrease the surface tension in the foam to allow it to spread across an area more easily and so starve the flames of oxygen.

Unfortunately, the foam can be washed away, leading the PFAS to pollute nearby water courses and soil.

They are also often used as a treatment in waterproof clothing or food packaging, such as paper bags used in takeaway food, and pizza boxes, to help resist grease stains seeping through. Similarly they can be used to treat carpets and soft-furnishings, and one study found them in 60% of bedding and clothing marketed for children. But it’s not yet known if this kind of exposure represents a health risk.

It currently isn’t clear what levels of PFAS can transfer into our bodies through our skin and food, but scientists do warn that there is a risk of contamination through the inhalation of PFAS-laden household dust. Children, in particular, might also put treated soft furnishings into their mouths directly. But exactly how much of these chemicals enter the body in that way has not been well studied, and they do tend to have a shorter half-life in the air than they do in water.

The other place where PFAS are commonly used is in plastic, such as food containers. They are used to help make plastics more chemically resistant to staining, but here too scientists have found the PFAS can leach out into our food.

And in 2022, the Environmental Working Group, an environmental non-profit found another source – sewage sludge. It estimated that almost 20 million acres (80,937sq km) of US cropland has been contaminated with PFAS through the use of sewage sludge. This sludge can contain microplastics and also the long-lived chemicals themselves that our kidneys have worked so hard to remove and excrete from the body. Once in the soil, they can then find its way back into our food system.

Read more about how forever chemicals and microplastics are getting into our food in this detailed article by environmental journalist Isabelle Gerretsen.

—

Join one million Future fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter or Instagram.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “The Essential List” – a handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife, Travel and Reel delivered to your inbox every Friday.