The French Ecology Ministry has lodged a complaint after industrial plastic microbeads have been found washed up on several beaches on the French Atlantic coast, polluting the shoreline.The complaint, announced on Saturday, January 21, calls for “justice” against an unnamed defendant, “X”.Microbeads are little industrial beads, 5mm across, which are used in the production of most plastic products, when they are melted down to make everyday plastic objects. In French, they are often known as ‘GPI’ (granulés plastiques industriels). The beads are also sometimes called ‘siren tears’.They are different from other microplastics, which occur when existing plastic objects break down.‘Extremely invasive pollution’It comes after several mayors made complaints from coastal towns, including Pornic (Loire-Atlantique) and Sables-d’Olonne (Vendée), and a complaint by Pays de la Loire regional president, Christelle Morançais, about the hundreds of thousands of beads washing up on the coast.Ms Morançais complained of “extremely invasive pollution [with] dramatic consequences for flora and fauna”. She laid the blame at the door of “rule-breaking companies that devastate our oceans, our water, and our environment”.A la suite du déversement sur les plages de notre littoral d’une quantité très importante de granulés plastiques industriels, j’ai décidé de porter plainte contre X devant le procureur de la République. pic.twitter.com/6nMGH74t1I— Christelle MORANÇAIS (@C_MORANCAIS) January 19, 2023Christophe Béchu, Ecology Minister, has now responded, saying: “The state is at the side of your campaigns, and I am letting you know of our intention to take this to court.” He said that GPIs were an “environmental nightmare…the equivalent of 10 billion plastic bottles”.Microbeads were also noticed in Finistère at the end of last year, and were also detected across beaches in Vendée, Morbihan, and in Loire-Atlantique. ‘Poison for fish’Hundreds of people took part in a beach cleaning session on Pornic beach this weekend, to help clear up the beads and to raise awareness of their denunciation of the pollution. They took part in a demonstration, and held up placards reading: “Plastic pollution = guilty industry!” and “Poison for fish”.Lionel Cheylus, spokesperson for the NGO foundation Surfrider, told the AFP: “We think that it has come from a container, which, maybe, was damaged a while ago, and because of recent storms, has opened.“We found these pellets in December in Finistère, and then in summer in Sable d’Olonne, and then here in Pornic, then Noirmoutier. It’s pollution that moves.”Mr Cheylus said he believed that Storm Gérard had been moving the beads around more. Related articlesTourists in France ‘swimming in a plastic soup’Marseille beaches covered in waste after storms drag rubbish into seaHaving to clean beaches is shameful

Author Archives: David Evans

Plastic bottle deposit return scheme finally looks set to start in England

Plastic bottle deposit return scheme finally looks set to start in England Campaigners say long delay is adding to pollution and government would be betraying manifesto promise if glass is not included The launch of a long awaited deposit return scheme for plastic bottles is expected to be announced by the government. Five years after …

Continue reading “Plastic bottle deposit return scheme finally looks set to start in England”

The surprising environmental benefits of single-use coffee pods

While convenient and popular, single-use coffee pods are viewed by many as an environmental nightmare. But despite the piles of discarded capsules this brewing method leaves behind, it might not be as terrible for the planet as you think.In some cases, brewing a cup of joe in an old-school filter coffee maker can generate roughly 1½ times more emissions than using a pod machine, according to an analysis by researchers at the University of Quebec at Chicoutimi in Canada.The study adds to a growing body of research that shows assuming packaging does the most harm to the environment is often misguided. Instead, experts say, it’s important to look at a product’s entire life span — from the time it’s made to when it hits the landfill — to figure out which changes might have the biggest effect on improving sustainability. In the case of brewing coffee at home, this latest study shows that it largely boils down to not wasting water or coffee.“As a consumer, what we’re left with is the visible waste in front of us, and that often tends to be packages and plastics,” said Shelie Miller, a professor of sustainable systems at the University of Michigan School for Environment and Sustainability, who was not involved in the new analysis. “But the impact of packaging, in general, is much, much smaller than the product itself.”Here are four takeaways from research that can help you lower the carbon footprint of drinking coffee:Less coffee = fewer emissionsThe recent study, which looked at four common brewing techniques, found that instant coffee appears to produce the least amount of emissions when the recommended amounts of water and coffee are used. This is in part because there is typically a small amount of instant coffee used per cup and boiling water in a kettle tends to use less electricity compared to a traditional coffee maker. What’s more, the method doesn’t produce coffee grounds that have to be thrown out, according to the study’s researchers.Traditional filter coffee, on the other hand, has the highest carbon footprint, mainly because more ground beans are used to produce the same amount of coffee, the researchers wrote. This method, the researchers noted, also tends to consume more electricity to heat the water and keep it warm.“At the consumer level, avoiding wasting coffee and water is the most effective way to reduce the carbon footprint of coffee consumption,” said Luciano Rodrigues Viana, a doctoral student in environmental sciences at Chicoutimi and one of the researchers who conducted the analysis.How you make coffee mattersThe environmental impact of coffee is heavily influenced by how people prepare their drinks, Rodrigues Viana said.For example, in the case of instant coffee, if you use 20 percent more coffee and heat twice the amount of water, which often happens, then the data suggests coffee pods might be the better choice.Meanwhile, coffee-pod machines are typically designed to use the ideal amount of coffee and water, leading to less of both being wasted. Compared to traditional filter coffee, drinking about a cup of the beverage brewed from a pod saves between 11 and 13 grams of coffee, the data shows.“Sometimes it’s really counterintuitive,” said Andrea Hicks, an environmental engineering expert at the University of Wisconsin at Madison. She conducted a similar analysis comparing different brewing methods, and also found pods had less environmental impact than the conventional drip filter method, and in some cases were better than using a French press.“Often people assume that something reusable is always better, and sometimes it is,” Hicks said. “But often people really don’t think about the human behavior.”For instance, the latest analysis found the benefits of pods can be lost if their convenience encourages people to drink two cups instead of one.There are other factors to consider: How your electricity is generated plays an important role, Rodrigues Viana added. A cup of coffee prepared using electricity mostly generated by fossil fuels produces about 48 grams of CO2 equivalent, the analysis found. In comparison, a cup made using primarily renewable energy emits roughly 2 grams of CO2 equivalent.And other research has shown that adding milk can “drastically increase” the overall carbon footprint per serving.Don’t fixate on packagingTo be sure, producing and discarding pods can have an impact on the planet. But studies show that the lion’s share of the environmental effects of drinking coffee come from producing the beans and the energy needed for brewing.“Regardless of the type of coffee preparation, coffee production is the most GHG-emitting phase,” Rodrigues Viana and his fellow researchers wrote. “It contributed to around 40 percent to 80 percent of the total emissions.”Packaging accounts for a much smaller share, the data shows. Here’s the math for pods: Manufacturing them and sending the used ones to a landfill generates about 33 grams of CO2 equivalent. Producing 11 grams of Arabica coffee in Brazil — the amount that can be saved by using a pod rather than brewing filtered coffee — emits close to double that amount: about 59 grams of CO2 equivalent.But if you want to help reduce the impact of packaging, you can recycle used pods or switch to reusable ones.Bottom line: Be mindfulAll that said, the first thing to do might be to ask yourself if you actually want that cup of coffee and whether you’re going to drink all of it, Miller said.“There’s not necessarily a really easy rule of thumb to tell consumers, ‘Here’s the best environmental option,’” Miller said. Instead, she recommends focusing on reducing waste and consumption overall and trying to be as efficient as possible with the resources you have.“It really comes down to being mindful about the products that you consume and trying not to waste our products,” she added.Sign up for the latest news about climate change, energy and the environment, delivered every Thursday

EU lawmakers back ban on 'waste colonialism' plastic exports

What will become of that plastic bottle you just diligently placed in the recycling bin? If you’re reading this from the European Union, there’s a chance it might end up far, far away — possibly fueling an industry associated with serious environmental and health risks.Official figures from statistics agency Eurostat show the EU exported 1.1 million tons of plastic waste to countries outside the bloc in 2021. And according to the European Parliament, around half of all the plastic collected in the EU for recycling is shipped elsewhere, with the number one recipient being Turkey.

The nongovernmental organization (NGO) Human Rights Watch (HRW) investigated the impact on workers and local communities there. “They’re the ones bearing the brunt of the impacts of what is known to be a hazardous industry.”

HRW environmental researcher Katharina Rall explained. “People talk to us about the health effects or what they believe are the effects, linked to the work itself, the fact that they’re working in factories where they’re potentially inhaling toxic [air].”

Workers said they lacked access to protective equipment, with some claiming to have worked there since they were children. Rall also noted shoddy enforcement of environmental laws for nearby communities.A house made of recycled plasticTo view this video please enable JavaScript, and consider upgrading to a web browser that supports HTML5 video

Tighter waste rules coming

But if you’re concerned about that plastic bottle, you may be pleased to hear EU waste management laws are due for a reboot. On Tuesday, a clear majority of the European Parliament voted in favor of banning the export of recyclable plastic waste to non-OECD countries, which includes major recipients like Malaysia, Vietnam and Indonesia and other former colonies of European powers.

In 2021, an activist group in Indonesia built an art installation out of plastic wasteImage: Prasto Wardoyo/REUTERS

This goes a step beyond the European Commission’s own proposal from late 2021, which would only allow such exports with prior consent. Outward shipments of non-recyclable, unsorted plastics were already banned in early 2021 to align the bloc with international standards.

A majority of EU lawmakers also supported phasing out shipments to OECD countries, meaning Turkey would be off the cards in the second half of this decade. In addition, non-EU export of all kinds of waste (which totalled 32.7 million tons in 2020) should only be allowed to non-OECD countries if they explicitly agree to take it and show they can deal with it sustainably, the European Parliament explained in a press release.

“We must turn waste into resources in the (EU) common market, and thereby take better care of our environment and competitiveness,” said Pernille Weiss — the center-right European Parliament member who led the report, which was put to the vote on Tuesday — in the statement, the underlying idea of which is that the EU must start to take more responsibility for its own waste, as well as working to reduce it.

Full plastics ban ‘only a matter of time’

With the EU legislature’s stance now clear, the ball passes to the EU member states, who must adopt a position before negotiations on the final legal package can begin.

Rall said it wasn’t yet clear which way the EU national governments would go on the plastics export ban. But for her, it is “only a matter of time” before the EU implements such a ban, not least because of the documented human rights issues.

“At some point there will be very few options left on where to export the waste,” she told DW.

China banned imports in 2017, and Turkey did so temporarily in 2021, Rall explained, while at the same time noting that the practice may be on the rise elsewhere, citing both West and East Africa as new destinations for European, US and Canadian waste exports.

In fact, EU plastic waste exports are on the decline, having peaked in 2014, as figures from Eurostat show. China was for a long time the major recipient of EU plastic waste, a title that passed to Turkey after Beijing introduced its ban on imports in 2017.

Fewer exports means greater responsibility

With exports rules likely to tighten regardless of the exact outcome of EU negotiations, the onus should shift to domestic processing capacity, as well as waste reduction. The EU plastic recycling industry had a turnover of €7.6 billion ($8.2 billion) in 2020, according to industry body Plastic Recyclers Europe, with sorting capacity having significantly increased over the past two decades.European countries are being pressured to up their own recycling effortsImage: Rolf Vennenbernd/dpa/picture alliance

In the past, firming up rules has prompted fears that more plastic would be incinerated or put to landfill. Within the EU, around 40% of plastic is used for energy recovery, 33% is recycled, and 25% is put to landfill, according to the European Parliament.

But Theresa Mörsen of the NGO Zero Waste Europe says changed export regimes would also encourage domestic reform. “If plastic waste is retained inside the EU, it will actually facilitate better sorting and recycling of the existing plastic,” she told DW. It would also encourage member states to enact laws that require greater recyclability, according to Mörsen. “We see a lot of non-recyclable things that end up either being incinerated or exported through illegal channels,” she explained.

For campaigners like Mörsen and Rall, Tuesday’s vote is a clear win. “Another important step towards ending waste colonialism,” said Lauren Weir of the Environmental Investigation Agency.

Edited by: Andreas Illmer, Nicole Goebel

Bundesliga: Reusable cups mandatory in stadiums

Beer from a disposable cup and currywurst with fries on a plastic plate? Those images could soon be a thing of the past in German football stadiums.As early as the Bundesliga’s re-start after the World Cup and winter break, catering operators in stadiums must also offer reusable cups by law, at the same price as the disposable version.

The new requirements from the Packaging Act have been in force since January 1, 2023. They oblige companies such as restaurants, canteens, supermarkets or cafes that sell takeaway food and drinks to also offer their products in reusable packaging.

This also applies in football stadiums, right down to the fourth tier of German football. However, in this case only for beverages. For food, stadiums may continue to offer disposable containers for food as the only option if they are made of pure cardboard, wood or aluminum. Most stadiums currently offer paper plates and wooden cutlery.

According to Environmental Action Germany (DUH), 17 of 18 Bundesliga clubs had voluntarily implemented the new requirements at the start of the season. Schalke 04, the last club in the Bundesliga to switch, also did so on January 1, 2023. Just five years ago, only 10 of 20 clubs in the Premier League used exclusively disposable cups, causing a mountain of waste of more than 8.5 million plastic cups every year.

Bundesliga leading by example

According to Germany’s Environment Minister Steffi Lemke, this makes Germany a pioneer throughout the European Union. German football also plays a pioneering role internationally in the area of sustainability, expert Tanja Ferkau confirms to DW. A look at the corner flags used to depict global warming in German footballImage: Wunderl/BEAUTIFUL SPORTS/picture alliance

This is because, starting next season, ecological as well as economic and social sustainability criteria will become a mandatory part of the German Football League Association (DFL) licensing process with the goal of becoming the most sustainable league in the world. Some of the criteria could have been stricter, but Ferkau explains that they have to ensure they can also be implemented by a team in the third tier.

The German Football Association (DFB) is also getting involved with several measures and campaigns in the DFB Cup, the Women’s Bundesliga and the 3. Liga. There are “climate logos” on the captain’s armbands, vegan bratwursts or corner flags with the “warming stripes.” These are a visual representation of scientific data from climatologists and are intended to illustrate the issue of global warming.

“Environmental pioneers” St. Pauli, Bremen and Freiburg

Some Bundesliga clubs have been engaged with the issue of environmental protection for much longer than others. DUH highlights three: FC St. Pauli, SC Freiburg and Werder Bremen. “These are clubs that have thought about environmental protection from the very beginning, since the late 1990s, when it wasn’t an issue in football at all. They have set trends,” DUH’s head of circular economy, Thomas Fischer, told DW.

Among other things, Freiburg has equipped its stadium with one of the world’s largest solar roofs, uses green electricity and has relied on returnable cups for decades. Werder Bremen is a role model when it comes to sustainable mobility: The public transport connection is exemplary, and there is also an infrastructure for thousands of bicycles that can be parked at the stadium not to mention a good network of footpaths. St. Pauli, meanwhile, selects its partners according to ecological and social criteria.

Alongside energy, transport, emissions and waste, merchandising is one of the most important action areas in football, says Fischer. Sporting goods manufacturers Nike and Puma have already made the switch. They say they use 100 percent recycled polyester for jersey production. At Adidas, the figure is just over 90 percent, but the Bayern Munich jersey is already made exclusively from recycled polyester. According to the DUH, second tier St. Pauli are “environmental pioneers” amongst German teamsImage: Oliver Ruhnke/IMAGO

DUH: “Eastern German clubs need to catch up”

However, Fischer reports that there are also clubs that are very defensive about the issue, such as Schalke 04 or VfB Stuttgart. Many East German soccer clubs also have a lot of catching up to do, he adds. “Dresden, Aue, Chemnitz, Zwickau – they don’t stand out with pilot projects either. There, we’ve always noticed a very defensive attitude.” The reactions of these clubs were often monosyllabic, “sometimes even almost aggressive.” And that’s when he realized, “Okay, they don’t understand.”

That’s why it’s immensely important that the DFL set targets to create a binding force in the areas of resource management, waste, traffic emissions, merchandising, so “that even those who don’t want to deal with these issues, have to.”

Overall, Fischer believes German football can still go a step further and hopes that green energy, regenerative energies for electricity use and sustainable turf heating will become standard.

In addition, it could play a big role in terms of mobility. “How do people travel? Can we do without short-haul flights? You don’t have to fly from Berlin to Frankfurt, there’s a good ICE train connection there. Do you need your own fleet of company cars? Maybe you could also ride a bike if you live close by.”

The least that could be done in the near future is to switch to reusable food containers. That would be a another significant step in club’s obligations that would continue to eliminate unnecessary disposable waste week after week.

This article was translated from GermanKick off! – Special: Midseason Review, Part 1To view this video please enable JavaScript, and consider upgrading to a web browser that supports HTML5 video

England is banning some single-use plastics. Activists say it’s a small step

Starting in October, the country will prohibit plastic plates, cutlery and other items. Environmental advocates are pushing for a more comprehensive measure.As England announced over the weekend that it would ban several single-use plastic items, including cutlery and plates, environmental advocates greeted the measure with more of a tepid clap than uproarious applause, seeing it as a better-late-than-never measure that leaves more changes needed.While they were grateful for action, several activists said the move came well after similar measures by England’s neighbors and did not ambitiously address the proliferation of disposable plastic, which ends up in landfills and oceans and takes decades to break down.“It is a step in the right direction,” said Nina Schrank, a senior campaigner for Greenpeace U.K. “But it is a small step.”Starting in October, England will ban single-use plastic plates, trays, bowls, cutlery and some polystyrene cups and food containers. The government said that England uses an estimated 2.7 billion items of single-use cutlery and 721 million single-use plates per year, but that only 10 percent are recycled.England banned plastic straws, cotton swabs and drink stirrers in 2020. In announcing the new ban on Saturday, government officials said they were looking into further measures, including a ban on plastic items including wet wipes and tobacco filters, or mandatory labeling to help people dispose of such items correctly.England’s environmental department said in a statement that the government would be “pressing ahead” with a plan for a deposit return initiative for drink containers, and “consistent recycling collections in England.”Rebecca Pow, an environment minister, said in a statement, “Plastic is a scourge which blights our streets and beautiful countryside, and I am determined that we shift away from a single-use culture.”Governments across the globe have employed single-use plastic bans as a way of reducing plastic, most commonly focused on products, like straws and bags, that can be made from other material.Advocates say that the bans have been largely successful in limiting the targeted types of plastic products, but that a more comprehensive approach is needed. And they say England has fallen behind its peers after Brexit severed Britain from Europe.The European Union approved a ban on single-use plastic items in 2018, which went into effect three years later. England’s neighbors, Scotland and Wales, each banned a similar list of items last year. (Northern Ireland, the fourth constituent country in Britain, has not.)The United States has not banned any single-use plastic products at the federal level, but some cities and states have their own bans on items, including plastic bags and straws. Some states, such as California, have gone further to reduce single-use plastic items, aiming to phase out single-use packaging that is not recyclable or compostable.Environmental advocates say England’s coming ban, which does not include plastic takeout containers, does not go far enough.Tolga Akmen/Agence France-Presse — Getty ImagesEurope’s ban has had mixed results, with some countries showing more progress than others, according to a report by Seas at Risk, a group based in Brussels. The ban eliminated 10 single-use plastics, but did not stop member countries from going further. The European directive also addresses other common forms of single-use plastics, including takeout food containers, that England did not ban.“If you are only banning some items and overlooking other products, then it is not sufficient,” said Frédérique Mongodin, senior marine litter policy officer at Seas at Risk.As for the timing of the move? “It’s very late,” she said.With the European directive underway, activists are looking beyond individual product bans to measures including the promotion of reusable containers.Ms. Schrank, the Greenpeace official, said many of the largest sources of plastic waste remained untouched, including food and grocery packaging. Snack bags and fruit and vegetable packaging are among the most common items found in plastic waste, she said.Instead of targeting them individually, she said she would like to see an aggressive government target to reduce single-use plastics by 50 percent.“We’re being fed little treats here, when the big real questions are being unanswered,” Ms. Schrank said.Nor is the issue with single-use items limited to plastics. Larissa Copello, consumption and production campaigner for Zero Waste Europe, said replacing single-use plastic with single-use items made of other materials only helped so much.“The issue of single use is not only about plastic, but single-use paper and single-use glass,” she said. “It’s all about the consumption of products that are only used once and thrown away.”For activists in Britain, eyes are on what comes next. Steve Hynd, policy manager at City to Sea, an environmental organization based in Bristol, said the ban was welcomed but “these are very much minimum agreed standards.”“The ban will help England catch up with other countries that already implemented similar bans years ago,” he said. “But for England to be true ‘global leaders’ in tackling plastic pollution like this government claims to be, we need them to go much further.”

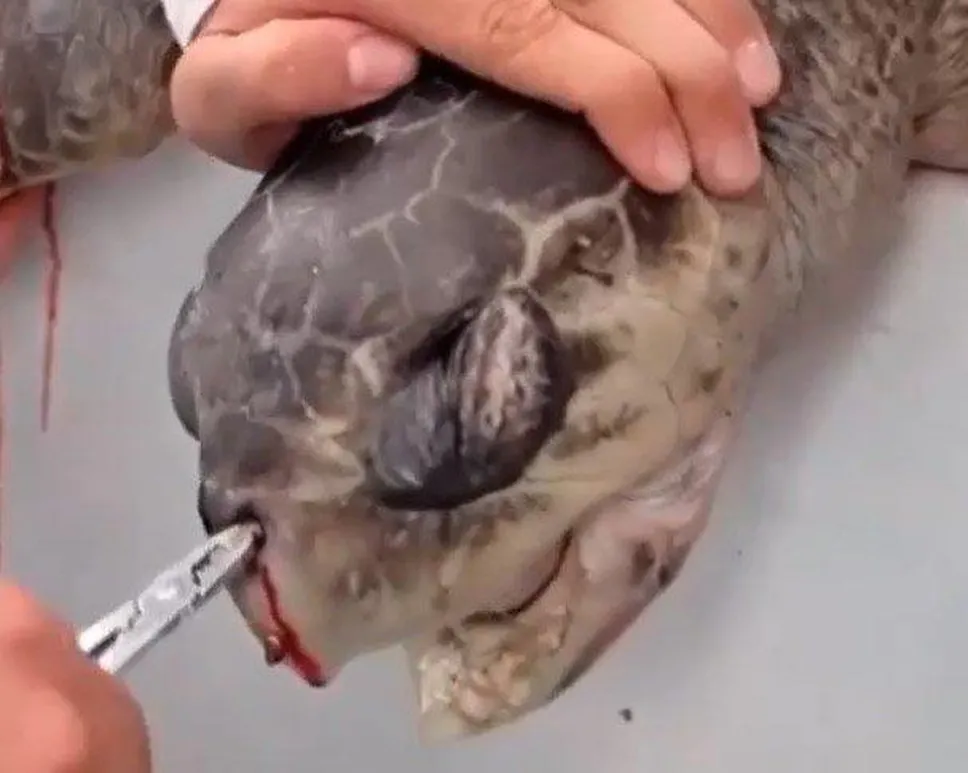

Kitchener mother finds “sneaky plastics” in household waste

WATERLOO REGION — When Rebecca McIntosh of Kitchener signed up for the zero waste challenge, the married mother of two found “sneaky plastics” among the garbage she never thought about before.McIntosh didn’t know it, but she had been “wishcycling” — assuming a container or bag could be recycled, so it was tossed into the blue box.But during the zero waste challenge, she scrutinized every piece of garbage her family produced. The five-day challenge, run by the Kitchener charity Reep Green Solutions, is to have each member of the household produce no more waste than what a single Mason jar can hold.“We think we lead a low-waste lifestyle, but until you pay attention you don’t really know where all your waste comes from,” said McIntosh.She long believed ice cream containers could be recycled. Wrong: they contain plastic between the cardboard-like layers and are not recyclable. Cardboard alone and most plastics on their own can be recycled, but not when combined into a single product. “That was eye-opening,” said McIntosh.McIntosh and her family have done the challenge twice. The real benefit is looking closely at the garbage produced, and thinking about ways to reduce it.“We made changes afterwards,” said McIntosh. “Now we buy ice cream in a full, plastic container that is recyclable, or a glass one.”The UN Environment Assembly voted in March 2022 to end plastic pollution, and forge an international legally binding agreement by the end of 2024.When Canada was chairing the G7 group of advanced economies in 2018, it called for reducing the use of plastic. It spent years developing new regulations.Ottawa’s first phase of a multi-year program to eliminate plastics came into effect about a month ago with a ban on importing or manufacturing six plastic items: plastic checkout bags, cutlery, stir sticks, straight straws, chopsticks and takeout containers. Businesses have until Dec. 20, 2023, to use up existing inventories and start using replacements.Beginning in June, plastic ring carriers can no longer be made or imported into Canada. Businesses have a year to use up existing supplies, but beginning in June 2024, ring carriers will be banned.The government will also prohibit the export of plastics in the six categories by the end of 2025, making Canada the first among peer countries to do so internationally, says a federal government statement.The video “The Story of the Sea Turtle with the Straw” inspired millions of people to stop using plastic straws.screen shot from the viral video: The story of the sea turtle with straw in it’s nostril.Over the next decade, the world-leading ban will eliminate an estimated 1.3 million tonnes of hard-to-recycle plastic waste and more than 22,000 tonnes of plastic pollution, which is equivalent to over a million garbage bags full of litter, says the statement.But if you don’t eat fast food, the federal ban will have little impact.“We don’t drink bottled water, we don’t use plastic straws, the single-use plastics are not something we had a lot of in our lives anyway,” said McIntosh.For McIntosh and her family, “sneaky plastics” are the problem.“It was more the hidden plastics, the ice cream container with plastic layers, or even meat packaging you think is a paper material but it is actually plastic, so it’s garbage,” said McIntosh.Plastics pollution is so widespread, microscopic plastics are showing up in human blood, poop and placenta.But Jennifer Lynes Murray, a University of Waterloo professor who teaches business and environment, social marketing and enterprise strategies for social accountability, has worked for more than a decade on one of biggest generators of single-use plastic waste — concerts, sporting events and festivals.For a decade Murry worked with artists and musicians, venues and promoters to ban the use of plastic cups at venues. Instead, the fans can bring refillable containers, and free water is provided at filling stations. The Hillside Festival in Guelph has adopted many green initiatives, said Murray.The federal government successfully battled other, huge environmental challenges.In the 1980s Ottawa negotiated an acid rain reduction treaty with the U.S. that reversed the acidification of many lakes in Ontario and Quebec.In the 1970s an international treaty was approved in Montreal to eliminate chlorofluorocarbons from aerosol sprays. The harmful chemicals caused huge holes in the ozone layer. As a result, the holes are shrinking and will be closed entirely in about 20 years.The same thing can happen with plastics, said Murray.“We lived without plastics prior to the 1950s, so there are definitely ways we can live without them again,” said Murray.“It is a three-pronged challenge — how willing are people to make the changes, how available are the alternatives and how will the government encourage that through policies and regulations?” said Murray.She watched a single image galvanize the public — a sea turtle with a straw stuck in its nose. The 2015 pictures and video showed researchers removing a plastic straw that was embedded in the turtle’s nostril.“It created this whole movement, and within a year nobody was using plastic straws and it was really widespread as well,” said Murray. “When you get the momentum, things can happen quickly.”Canada needs to ban a lot more plastics than the six items associated with takeout food, and it needs to act more quickly, said Sarah King, the Vancouver-based head of the Oceans and Plastics Campaign for Greenpeace.“The current ban covers less than three per cent of the plastic waste we generate in Canada,” said King.The blue box program is as widely loved as it is deeply flawed, she said, and only encourages and enables more widespread use of plastics.“Recycling we know is not the solution to the plastic waste and pollution crisis,” said King. “This whole idea of plastic recycling is a myth. because many people across this country have come to learn that less than nine per cent of plastic is recycled in Canada.”King said PVC, the black plastic pipe, should also be banned. Polystyrene — a white, spongy material widely used for coffee cups and clamshell takeout containers — should be banned as well, she said.Polystyrene “is highly polluting in its production. And due to the nature of the material, when it ends up in the environment it breaks apart very easily and spreads,” said King.SHARE:

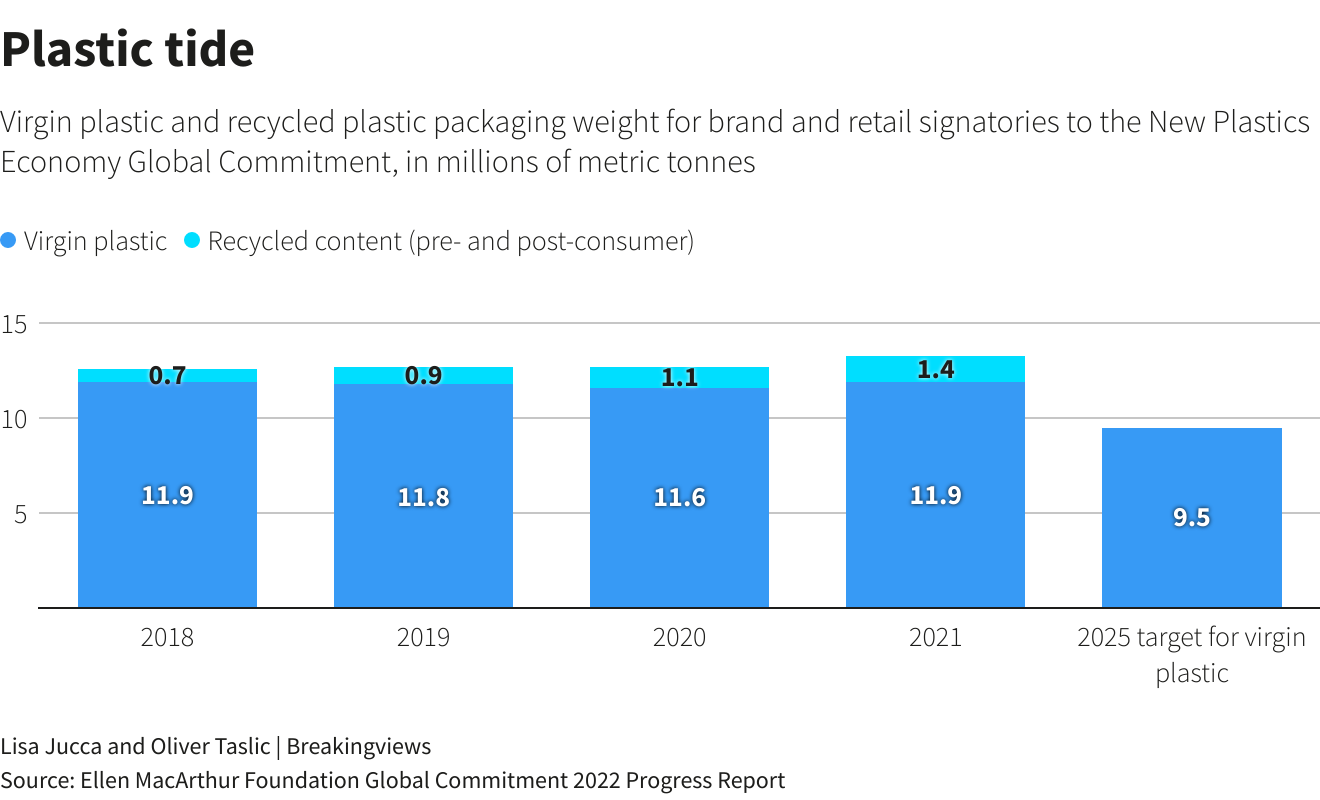

Investors sit on a plastic waste ticking bomb

MILAN, Jan 13 (Reuters Breakingviews) – Investors should worry about a rising plastic tide. The pandemic and a war in Ukraine have focused money managers’ attention on supply chain disruption and energy security risks. Yet as the world continues to drown in packaging waste, the public and private sectors may come after big users like PepsiCo (PEP.O), Coca-Cola (KO.N) and Mars.Four years after the consumer goods giants signed up to voluntary reduction targets under the New Plastics Economy Global Commitment, progress is disappointing. Ellen MacArthur Foundation data shows that the packaging employed by companies like PepsiCo, Mars and Coca-Cola increased its usage of virgin plastic, made from fossil fuels rather than recycled materials, by 5%, 3% and 11% respectively between 2019 and 2021. That makes it unlikely they can meet their commitments to curb its use by 5%, 20% and 25% by 2025.Big plastic users are also making insufficient progress in using recycled material. The latter amounts to just 10% of plastic packaging used by pact signatories. Reusable containers, the most environmentally friendly form of packaging, amounted to only 1.2% of the total in 2021, and that figure is decreasing.Despite citizens’ effort to sort out used plastic for collection, especially in Europe, only 9% actually gets recycled each year, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development says. In the United States 73% of plastic waste ends up in landfills, where it takes up to 500 years to decompose. The rest gets incinerated or washes up on developing countries’ shores. That will only worsen as annual demand of about 450 million tonnes a year is expected to treble by 2060.Solving the plastic challenge is complex and expensive. Plastic comes in different types that cannot be bundled together. Certain materials or additives make it difficult to recycle. Substituting plastic with biodegradable material can be expensive. Using recycled plastic, while less energy-intensive than creating virgin plastic, can cost more overall.Yet, having pledged to act, big corporates are in a vulnerable position. Danone (DANO.PA) is facing a legal challenge over its plastic use. In March, 175 governments agreed to work out binding laws to end plastic pollution by end-2024. Around 70% of citizens surveyed last year in 34 countries want new anti-plastic rules.European investors’ greater focus on sustainability means they are more likely to hassle domestic laggards. But if governments decide to implement mandatory recycling quotas, rival U.S. late-starters would suffer the most. In a worst-case scenario, companies could face a collective $100 billion annual bill if lawmakers ask them to cover waste management costs in full, the PEW Charitable Trusts says.For investors, plastic inaction could become toxic.Reuters GraphicsFollow @LJucca on Twitter(The author is a Reuters Breakingviews columnist. The opinions expressed are her own. Updates to add graphic.)CONTEXT NEWSRepresentatives of 175 countries endorsed in March a landmark resolution to develop international legally binding instruments to end plastic pollution. Negotiations on the new legal instruments kicked off on Nov. 28 with the aim of finalising a binding agreement by 2024.Germany will ask makers of products containing single-use plastic to contribute to the cost of collecting litter in streets and parks from 2025 by paying into a central fund managed by the government. In 2008 the Netherlands introduced a packaging waste management levy.Corporate signatories of the New Plastics Economy Global Commitment launched by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation and the U.N. Environment Programme in 2018, which include PepsiCo, the Coca-Cola Company, Nestlé, Danone and Unilever, are likely to miss several if not all of their targets for tackling plastic pollution. That’s according to progress report by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation published in November.Collective use of virgin plastic by the signatories of the anti-plastic pact has risen 2.5% year-on-year to 11.9 million metric tonnes in 2021, bringing it to the same level it stood at in 2018. Meanwhile, the share of reusable plastic in packaging has fallen to an average 1.2% of total, the report showed.Editing by George Hay, Streisand Neto and Oliver TaslicOur Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles.Opinions expressed are those of the author. They do not reflect the views of Reuters News, which, under the Trust Principles, is committed to integrity, independence, and freedom from bias.

‘Forever chemicals’ expose need for systemic changes

Going back in time can reveal how far we still have to progress. In researching per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) for a recent article series, I found myself ricocheting between the present and the 1950s and 1960s. That was when the vast class of fluorinated compounds commonly dubbed “forever chemicals” first came into widespread use, morphing from wartime applications to a cluster bomb of consumer and industrial uses.

The pesticide industry was also “a child of the Second World War,” biologist Rachel Carson wrote in her magnum opus “Silent Spring,” published 60 years ago last fall. Synthetic insecticides had “no counterparts in nature,” she observed, yet “we have allowed these chemicals to be used with little or no advance investigation of their effect” on ecosystems or ourselves. Like pesticides, PFAS shot from laboratory to market without thorough safety testing, endangering public health and wildlife.

Despite subsequent advances in environmental legislation over the intervening decades, the U.S. approach to chemical regulation remains largely unchanged. We are still subjected to what Carson aptly termed an “appalling deluge of chemical pollution.”

Catering to corporations

Writing in The New Yorker shortly after Carson’s death in 1964, E.B. White noted a “basic flaw in our regulatory machinery. American justice holds the accused person innocent until proved guilty; somehow this concept has crept over into industry, where it doesn’t belong, and has been applied to products of all kinds. Why should a poison dust or spray… enjoy immunity while there is any reason to suspect that it may endanger the public health or damage the natural scene?”

Congress had a chance to correct this fundamental injustice when it enacted the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA) of 1976, but it let corporate priorities prevail. The law instructed the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to adopt those regulations “least burdensome” to industry, and it permitted continued use of roughly 60,000 chemicals (including the earliest ‘legacy’ PFAS) without review of their health risks.

An effort to strengthen TSCA in 2016 encountered strong industry pushback and accomplished only minimal reform, according to a recent ProPublica report. The workload of the agency’s chemical division grew markedly as it strove to undertake more chemical reviews, but its funding remained stagnant.

Greatly increasing the funding and staffing of EPA’s chemicals division would certainly improve chemical oversight, observed Kyla Bennett, an ecologist and lawyer who directs science policy for Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility (PEER), a nonprofit that supports whistleblowers and is pushing the EPA to protect consumers from PFAS in fluorinated plastic containers. “EPA doesn’t have the money, the bodies and the right expertise,” she said, nor does it have adequate time for evaluating new chemicals given a tight, statutory cutoff. The metric for success is “how many of these [approvals] they’ve gotten out in 90 days, not how well they’re protecting human health.”

“The whole system is broken,” Bennett added, due to corporate capture of the regulatory process — a dynamic she said persists under both Democratic and Republican administrations. Supervisors cycle from the agency to industry and back, and whistleblowers report that EPA managers change scientific conclusions, delete critical information and expedite approval of new chemicals to appease manufacturers.

Corporations are mandated to submit studies documenting safety risks, but in 2019 the agency stopped sharing those publicly and made the data difficult for their own staff to access, whistleblowers report. According to Bennett, even some safety data sheets — designed to inform workers and consumers of hazards—are now heavily redacted. Or, in place of where the form should appear in the database, there’s a blank page with a single word: “sanitized.”

A decade before the EPA was established, Carson had already observed the deference given to chemical manufacturers in what she called “an era dominated by industry, in which the right to make a dollar at whatever cost is seldom challenged.” Now, it appears that ‘right’ is almost never challenged: Among 3,835 new chemical applications submitted in the five years leading up to July 2021, journalist Sharon Lerner reported, EPA’s division of new chemicals did not decline a single one.

‘Regrettable substitutions’

Presented with clear evidence in 2001 that PFAS were endangering human health, the EPA negotiated a voluntary phaseout with some leading manufacturers for two PFAS compounds (among an estimated 4,700 in commercial use). In place of those ‘legacy’ compounds, the EPA permitted manufacturers to produce a second generation (“GenX”) of PFAS even though industry studies had demonstrated their health risks, Lerner revealed.

GenX is a classic case of a “regrettable substitution,” what Harvard University public health professor Joseph Allen defines as “the cynical replacement of one harmful chemical by another equally or more harmful in a never-ending game being played with our health.”

Industry always has the upper hand in this whack-a-mole “game” due to the sheer volume of new chemicals generated. The U.N. Environmental Programme reports that in 1965, a new chemical substance was registered on average every 2.5 minutes. Now, it’s every 1.4 seconds. The EPA is mandated to test 20 new chemicals a year but it’s failing to meet even that modest target.

The Precautionary Principle

Europe, in contrast, is moving away from the whack-a-mole approach to chemical management. According to the European Environmental Bureau, the European Commission plans to implement “a group approach to regulating chemicals, where the most harmful member of a chemical family defines legal restrictions for the whole family. That should end an industry practice of tweaking chemical formulations slightly to evade bans.”

For more than a decade, Europe has applied a common-sense restraint known as the Precautionary Principle in chemical regulations — requiring industries to assess risks and share data on hazards before substances go to market. Whereas in the U.S., chemicals are readily approved and only withdrawn when there is irrefutable evidence of human harm, often after decades of use.

While questions remain about the timeline and resources for implementing Europe’s new chemicals “Restrictions Roadmap,” the European Union has already banned about 2,000 chemicals since adopting a more precautionary approach. An additional 5,000 to 7,000 chemicals could be banned by 2030 under the new roadmap.

Paring back to essential uses and increasing transparency

Maine is pioneering a path that a growing number of scientists and policy specialists advocate — banning all PFAS except those deemed — in the language of LD 1503 — “essential for health, safety or the functioning of society and for which alternatives are not reasonably available” (such as critical medical devices).

A recent study found that alternatives exist for many consumer uses, but that options for industry substitutes are harder to assess—given a culture that keeps much production information proprietary. Far too often, companies use their right to confidential business information “as a cloak to keep things from the public and that’s wrong,” Bennett said.

3M, a leading manufacturer of PFAS, knew about the health risks of its formulations for half a century, evidence in lawsuits has revealed. Recently, the corporation announced plans to phase out PFAS manufacturing and use by 2025, but lack of transparency around how it defines and formulates these chemicals makes the outcome ambiguous. Its action comes in the face of mounting pressure from investors and tens of billions in anticipated litigation settlements as communities around the globe seek damages from chemical manufacturers for poisoned waters and health impacts that begin even before birth, resulting in “pre-polluted babies.”

Chemical corporations may not adopt greater transparency until forced to. But governments working to regulate and remediate PFAS can show the way. For the most part, Maine is making a good-faith effort to share information openly: posting data on sludge and septage sites to be tested, results from landfill leachate tests and public drinking water supply tests, updates on the status of the state’s well-testing, and recorded meetings of the PFAS Fund Advisory Committee.

The state could further improve information-sharing by hiring an ombudsperson to field residents’ questions and concerns, creating a more intuitive and readily linked web interface, and openly strategizing how to address the vast gap that remains between needs for PFAS water testing and treatment and agency capacities. Residents I interviewed in hard-hit areas voiced frustration over not having anyone to advocate for them within state government, feeling they were “put on the back burner” and might be left on their own without further help.

With Maine now mandating PFAS reporting from manufacturers, state agencies will need to resist the regulatory “corporate capture” evident at the federal level.

Open sharing on the part of government is essential on practical grounds — to expedite getting clean water to those still drinking PFAS, to facilitate a rapid transition to new product formulations, and to keep people informed about rapidly evolving science and policy.

More fundamentally, transparency can help to right a pernicious wrong. PFAS pollution represents a devastating betrayal of people who placed their faith in government to protect them and in corporations to consider the greater good. Choices made over decades in corporate board rooms, EPA offices and the halls of Congress violated that public trust.

“Who has decided — who has the right to decide — for the countless legions of people who were not consulted…,” Rachel Carson wrote about the indiscriminate use of toxic chemicals. In the case of PFAS, a small cadre chose the allure of big profits over the well-being of the world. If we hope to reverse those priorities in the years ahead, those who were “not consulted” will need to speak out.

October start set for ban in England of single-use plastic tableware

October start set for ban in England of single-use plastic tableware Sale by retailers and food outlets in England of single-use plastic tableware to be banned but not ‘shelf-ready pre-packaged food’ containers Single-use plastic plates, cutlery and a range of other items will be banned in England from October, to curb their “devastating” impact on …

Continue reading “October start set for ban in England of single-use plastic tableware”