A parliamentary committee wants Ottawa to limit the environmental damage and plug response gaps for marine cargo spills after a container ship lost more than 100 sea cans and was immobilized by a stubborn fire on the B.C. coast last year. The ZIM Kingston, owned by Greece-based Danaos Shipping Company Ltd., burned for a week after containers with combustible chemicals caught fire in the wake of stormy weather. But first a mass of containers, two carrying hazardous materials, washed overboard on the southern coast of Vancouver Island on Oct. 21. Debris from the containers, most of which have never been retrieved, is still washing up on West Coast shores, with reports last month suggesting it has reached as far north as Alaska. Get daily news from Canada’s National ObserverThe federal government, province and coastal communities aren’t operationally prepared to manage marine cargo spills, particularly those involving hazardous or noxious substances, the Standing Committee on Fisheries and Oceans determined after investigating the incident.There’s little ability to locate or salvage lost containers and contain long-term environmental impacts, and marine towing and firefighting capacity is deficient, the committee found. Coastal communities saw plastic pollution, marine debris and even a collection of fridges land on pristine beaches on northwest Vancouver Island after the spill, Lisa Marie Barron, the federal NDP fisheries and oceans critic, told Canada’s National Observer.Only four of the shipping containers have been found and retrieved from the shore, with the rest presumably littering the seabed. What people are reading NDP fisheries critic Lisa Marie Barron notes that more than 100 shipping containers are still missing from the ZIM Kingston cargo spill. Photo courtesy Lisa Marie Barron’s office It was shocking there was no extended effort to find or retrieve most of the missing containers, said Barron, who requested the standing committee study the issue. “If one of those containers had gold bars in them, we’d find a way to get it out of the ocean,” the MP for Nanaimo-Ladysmith said. The federal government, province and coastal communities aren’t operationally prepared to manage marine cargo spills, particularly those involving hazardous or noxious substances, a federal committee finds after the ZIM Kingston cargo spill in B.C. “Instead, they are just left there … and they will inevitably open, and the debris will wash up on our shores for years to come.” The committee investigation, launched in January, provided 29 recommendations to the federal government to improve the response to marine cargo spills. Although no fisheries were closed as a result of the cargo losses, the report stated, two shipping containers with a combined 42,000 kilograms of hazardous chemicals — potassium amyl xanthate and thiourea dioxide, used in mining and the textile sectors respectively — were lost at sea. The chemicals posed limited environmental risks because they were expected to dilute and be distributed widely in the ocean, according to Environment and Climate Change Canada and the Department of Fisheries and Oceans. But given there is no way to track containers, it’s difficult to monitor or mitigate any potential environmental concerns that might arise from their loss, said Alys Holland, youth co-ordinator with the Pacific Rim chapter of Surfrider Foundation Canada. And plastics — particularly polystyrene foam typically used in molded forms to protect goods or to make packing peanuts — will break down and persist for decades, if not centuries, to be widely distributed in the ocean and on shores, the committee heard. Polystyrene and nurdles from marine debris are much more insidious and have a longer-term impact than even oil, Stafford Reid, environmental emergency planner and analyst, told the committee. Given concerns were repeatedly raised about polystyrene foam, the committee recommended Canada spearhead an international effort to ban the product in marine transport packaging, and better monitor and research the particular plastic’s impact on the marine environment, Barron said. Shipping containers should also be outfitted with tracking devices to make it easier to locate them if they are lost, said committee member Liberal MP Ken Hardie. “Something that allows us to at least find out where they are, and to determine whether or not they could be salvaged in some cases, or if left alone, that they’re going to be fine,” Hardie said.There were also gaps in the response and communications in the ZIM Kingston incident, Hardie said. More proactive infrastructure needs to be in place, such as having pre-approved salvage and cleanup operators from B.C., First Nations and coastal communities that have the expertise and local knowledge of the region, he added. Canada isn’t prepared for a co-ordinated spill response for hazardous substances other than oil, particularly in terms of towing or firefighting, salvage capabilities or appropriate onshore facilities, experts told the committee. There’s also the need to improve transparency around what is washed overboard and the financial accountability of shipping companies involved in cargo spills, Barron said. The committee heard coastal and Indigenous communities and cleanup groups — on the front lines of a spill and the first to begin cleaning up debris — aren’t integrated in a spill response, nor do they get a specific understanding of what they’d find washing up on their shores. Not having specific cargo manifests available also makes it difficult to ensure the polluter continues to pay when marine debris washes ashore years after an incident, Barron noted. A shipping company is also only liable for cleanups for a maximum of six years after the incident and financial responsibilities are limited, the committee heard. As a result, the federal government should examine other mechanisms to ensure money is available immediately and in the long term for environmental damage from cargo spills, the committee recommended. Shipping volumes are on the rise along with extreme weather incidents and it’s imperative that the federal government develop a clear plan to prevent cargo spills, Barron said. Overboard cargo containers spiked in 2020/21 with an annual average loss of more than 3,000 containers due to severe weather, according to the World Shipping Council. “Coastal communities are the ones feeling the brunt of the debris that continues to wash up,” Barron said. “And if we’re just leaving containers in the sea, we need to have a cleanup plan that looks longer term.” Rochelle Baker/Local Journalism Initiative/Canada’s National Observer

Author Archives: David Evans

California passed a landmark law about plastic pollution. Why are some environmentalists still concerned?

California has a new environmental law that’s described as either a major milestone on the road to tackling the scourge of plastic pollution—or a future failure with a loophole big enough to accommodate a fleet of garbage trucks.

The law, which seeks to make the producers and sellers of plastic packaging responsible for their waste, divided California’s sizable environmental community during its development over the last few years. Key environmental organizations eventually came around to supporting it. But more than three months after Gov. Gavin Newsom signed what’s known as SB 54, the Plastic Pollution Prevention and Packaging Producer Responsibility Act is still stirring controversy.

After tense negotiations under pressure from a looming, high-stakes deadline, a compromise last summer won the day—and political leaders were able to claim a big environmental victory in the battle to take a bite out of the global plastics crisis.

Among its provisions, the law requires certain types of packaging in the state to be recyclable or compostable by 2032. It cuts plastic packaging by 25 percent in 10 years and requires 65 percent of all single-use plastic packaging to be recycled in the same timeframe.

Keep Environmental Journalism AliveICN provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going.Donate Now

Amid controversy, industry goes all in on plastics pyrolysis

In September, Dow declared a milestone in its effort to mitigate the flow of plastic waste. The big chemical company and Mura Technology took the wraps off a project in Böhlen, Germany, to build a plant based on Mura’s supercritical steam process. The facility will convert mixed plastic waste into hydrocarbon liquids that Dow will load into its ethylene cracker at the site for conversion back into new plastics.

In brief

Major chemical companies are backing pyrolysis plants for converting plastic waste into hydrocarbon feedstocks that can be turned into plastics again. They see it as a way to capture more plastics than they can with conventional mechanical recycling alone. But conducting pyrolysis at a significant scale will pose challenges. For instance, developers of pyrolysis processes have to tune their plants so they can convert a variety of polymers into products that petrochemical makers can use. Moreover, some plastics, such as polyvinyl chloride, can complicate the pyrolysis systems. How the technology works in the real world will affect the public’s perception of the plastics industry.

The plant will be the largest of its kind in Europe, diverting 120,000 metric tons (t) of waste per year from incinerators. It will be six times the size of Mura’s first plant, still under construction in Teesside, England. The partners hope to build additional facilities at Dow sites in Europe and the US for a total of 600,000 t of annual capacity.

“Böhlen is sort of a base case, and it will just get larger from there,” Oliver Borek, Mura’s chief commercial officer, said during a press conference. An executive from the engineering firm KBR, which is licensing the process beyond Dow and Mura, noted that his firm is already designing three plants in South Korea and one in Japan.

Petrochemical makers are fully behind the broad array of pyrolysis processes, like Mura’s, under development around the world. Nearly every large chemical company—Dow, BASF, Shell, ExxonMobil, LyondellBasell Industries, Sabic, Ineos, Braskem, and TotalEnergies, to name some—either has joined hands with a smaller firm developing a process or is creating its own.

These firms argue that pyrolysis can make up for the shortcomings of mechanical recycling, the familiar process of washing and repelletizing the plastics that consumers drop into blue bins. Only two polymers—the polyethylene terephthalate (PET) found in soda and water bottles and the high-density polyethylene in milk jugs and other such containers—are widely recycled at an appreciable scale. And it is difficult to get even these relatively homogeneous materials up to the contamination specifications needed for food-contact use. In all, mechanical recycling manages to capture only about 9% of plastics in the US, according to the US Environmental Protection Agency.

Recyclers can tackle a few more resins with depolymerization processes that break down polymers into their chemical precursors. For example, methanolysis can be used to recycle PET products like fibers and sheets that aren’t amenable to mechanical methods. And firms have been breaking down nylon using hydrolysis for many years.

We kind of joke sometimes that every day we need to make a birthday cake, but the ingredients keep changing all the time, and the birthday cake better be good and taste the same.

Eric Hartz, cofounder, Nexus Circular

But the bulk of the plastics we use—the candy wrappers, stand-up pouches, potato chip bags, protective packaging, single-use cups, frozen food bags, razors, toothpaste tubes, cotton swabs, and other objects of our daily lives—defy both mechanical recycling and depolymerization.

These items are constructed from multiple plastics that are nearly impossible to separate. Plus they are mostly made of polyolefins like polyethylene and polypropylene, which have strong carbon-carbon bonds that resist depolymerization. For these mixed plastics, pyrolysis is the industry’s only currently viable tool for recovering raw materials and making new polymers.

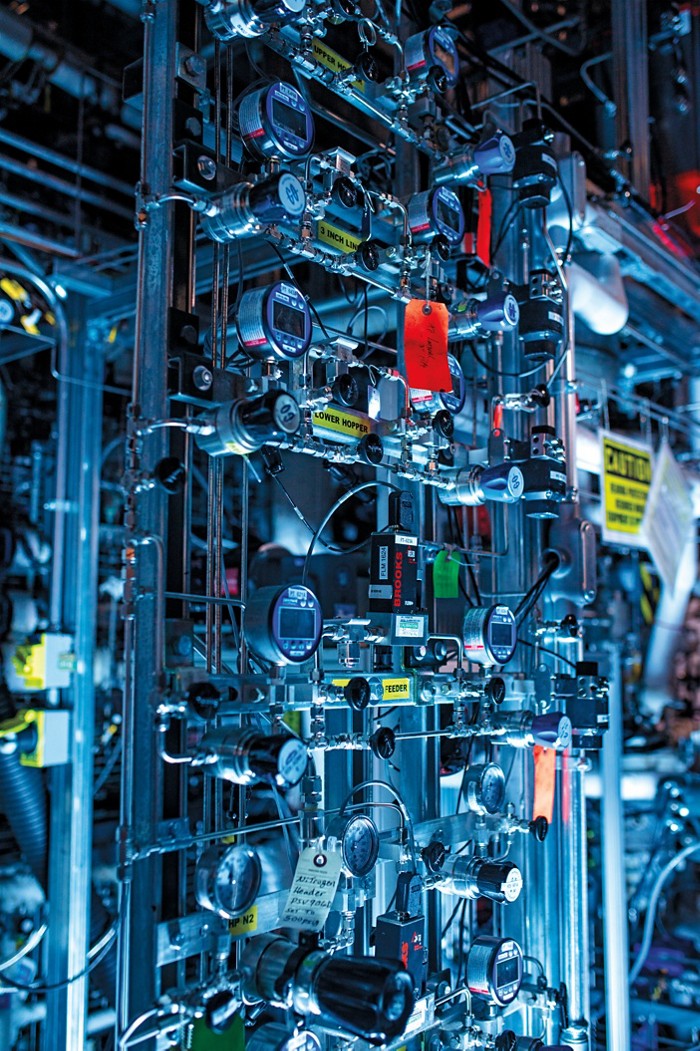

Honeywell UOP says it has run this pyrolysis plant at pilot scale for more than 2 years.Honeywell UOP

But a pyrolysis reactor isn’t a magic box that can make the plastics industry’s waste problems vanish. The process is superficially simple: using high temperatures in the absence of oxygen to break down plastics into a mixture of smaller molecules known as pyrolysis oil. Yet converting the different kinds of plastics that can end up as waste into an uncontaminated feedstock—such as the C5–C12 paraffins that would be an ideal naphtha feedstock for an ethylene cracker—poses considerable challenges. Plastics companies will need to overcome these challenges if they are to debunk environmentalists’ objections and meet their own goals for reducing waste and carbon emissions.

The pyrolysis cauldron

“We kind of joke sometimes that every day we need to make a birthday cake, but the ingredients keep changing all the time, and the birthday cake better be good and taste the same,” says Eric Hartz, cofounder and president of the pyrolysis firm Nexus Circular. “There’s a kind of art going on here when dealing with heterogeneous inputs as opposed to homogeneous. There’s not a perfect science to it about why some compounds behave the way they do in these environments.”

PyrolysisThis industry-backed path to plastics circularity chemically breaks down plastics into their component parts so they can be made into new plastics.

1. PretreatmentThe feedstock for pyrolysis plants is ideally made up of polyolefins such as polyethylene and polypropylene. Errant materials like oxygen-containing polyethylene terephthalate and chlorine-laden polyvinyl chloride are removed.

2. PyrolysisThe plastics are heated to about 500 °C in the absence of oxygen. The longer molecules break into liquid fractions like naphtha and diesel, solid cuts like waxes, and lower-molecular-weight gases. In most plants, roughly 10% of the product is char, a by-product.

3. Landfill disposalThe char is hauled to the landfill or can be added to asphalt or concrete. Most plants burn the gases for heat.

4. UpgradingFor the output to be suitable for making new plastics, adsorbents and hydroprocessing may be needed to remove chlorine, nitrogen, and other pollutants. A hydrocracker, or similar unit, is sometimes needed to further break down large molecules.

5. Using wasteThe naphtha is processed in an ethylene cracker to create ethylene and propylene, building blocks for more polyethylene and polypropylene.

One challenge of pyrolysis is the variability of the feedstock. The different polymers that are fed into a pyrolysis reactor break along different patterns. In particular, molecules with high degrees of branching crack more easily than linear ones.

According to a review paper by University of Minnesota Twin Cities bioproduct and biosystem engineer Roger Ruan and other scientists, polypropylene decomposes at 378–456 °C, while low-density polyethylene breaks apart at 437–486 °C, and high-density polyethylene at 452–489 °C. As a result, firms processing mixed plastic waste must select a temperature—normally over 500 °C—at which all the polymers they take in on a given day will break down.

However, temperature affects the composition of a pyrolysis unit’s output. Pyrolysis yields useful liquids, such as naphtha and diesel. But it also creates less-desirable waxes that might need to be broken down further. And pyrolysis makes lighter gases that are typically burned as fuel in the reactor. High temperatures and long reactor residence times might cut wax output and yield more naphtha, but they also create gases that have limited utility.

High temperatures can also lead to dehydrogenation, cyclization, aromatization, and Diels-Alder reactions, thereby creating more aromatics. “For fuels and so on, it’s fine,” Ruan says. “But sometimes we want naphtha feedstock for new plastics production; we don’t want a lot of aromatics.”

And feeding the wrong plastics into pyrolysis reactors creates inefficiency and can contaminate the output. PET contains oxygen and tends to form carbon dioxide, Ruan says. Polyvinyl chloride (PVC) yields chlorinated compounds. Additionally, some plastics have a lot of inorganic additives, such as carbon black, carbonate, and clay. They lead to the formation of char, which pyrolysis operators must dispose of as solid waste.

Environmentalists cry foul

Environmentalists loathe pyrolysis. And a growing number of jurisdictions, such as California, don’t consider it recycling at all. One critic is Jan Dell, a chemical engineer who founded and heads the Last Beach Cleanup, an environmental organization. She has helped larger environmental groups, such as the Natural Resources Defense Council and Greenpeace, prepare reports on the practice. For presentations, Dell has compiled 16 pages of objections.

One of Dell’s primary complaints is that pyrolysis facilities can’t actually accept the mixed plastic waste they claim they can. The residual PVC, PET, and other materials in the stream gum up the process too much.

“There’s too many types,” Dell says. “There are too many additives. You can’t recycle them all together, and separating them out defies the second law of thermodynamics. It is just impossible to reorder—like Humpty Dumpty—all these plastics once they’ve been put into a curbside bin.”

Dell contends that Renewlogy, a Utah-based company that was developing a pyrolysis plant, folded for precisely this reason. Her bullet points even contain a photo from a Nexus Circular facility in Atlanta showing bales of relatively clean plastic film of the type used at warehouses—evidence, she says, that the company isn’t accepting much postconsumer mixed plastic waste.

It is just impossible to reorder—like Humpty Dumpty—all these plastics once they’ve been put into a curbside bin.

Jan Dell, founder, the Last Beach Cleanup

A second charge is that pyrolysis is really incineration, even though pyrolysis reactors operate in the absence of oxygen. “If you look at just the pyrolysis vessel itself, no, there’s no burning. I have to agree with that,” Dell says. “But here’s the deal: How do you heat that pyrolysis vessel to the 900 to 1,500 °F you need? You heat it by incinerating the gas that comes off of it.”

Dell points to the pyrolysis company Brightmark, which disclosed to the EPA that 70% of the output from a plant it is building in Ashley, Indiana, will be gases that it plans to use for energy or flare. Brightmark now says those figures were submitted in error. Such gases represent only about 18% of the output, the firm says, and it is submitting the updated figure to the EPA.

Another critique has to do with scale. Dell says that roughly 120,000 t per year of pyrolysis and other chemical recycling capacity is currently onstream in the US. This represents a minuscule fraction of the overall plastics production of about 56 million t in North America in 2021, according to the American Chemistry Council. Just one new polyethylene plant has about 500,000 t of annual capacity.

To critics like Dell, pyrolysis is a greenwashing scheme meant to fool the public into thinking plastics are recycled more than they actually are. She points out that the industry, under similar pressure in the early 1990s, built up a lot of recycling capacity, only to shutter it when the projects proved unworkable and public attention faded. The industry is now repeating this pattern, Dell says.

Industry steps up

Industry executives say they are more committed than ever to recycling and are eager to practice pyrolysis at large scale. Their firms are building facilities that are bigger than before and are testing them in the real world. They are aware of the wrinkles in a pyrolysis-based recycling system and say they are determined to iron them out.

Manav Lahoti, global sustainability director for hydrocarbons at Dow, says experimentation will improve the systems over the long run.

“Sometimes you take this approach where there are successes and then there are failures and you singularly focus on the failures and say, ‘Oh, it’s just not working,’ ” he says. “Is there a momentum with companies like us to actually create a solution for this challenge? The answer to that is yes. And then along the way, you will have some successes and you will have some failures.”

Pyrolysis reactors at Nexus Circular’s plant in AtlantaNexus Circular

Brightmark is experiencing its share of obstacles. The plant that the company is starting up in Indiana, at a cost of $260 million, is designed to convert 100,000 t of mixed plastic waste per year into naphtha, diesel, and industrial waxes.

At the end of 2020, Bob Powell, Brightmark’s CEO, said construction of the facility was 80% complete and ready to ramp up production in 2021. But by April 2022, the company had manufactured only about 2,000 t of product. Now Powell says it will run at full scale next year.

“The biggest challenge at this time has been COVID,” Powell says. The pandemic delayed the delivery of equipment and made it difficult to find enough labor to work at the plant. The company also suffered a fire in May 2021 that it calls a “minor setback” in an email.

In another setback, Brightmark canceled plans to build a $680 million plant in Macon, Georgia, that would have been four times the size of the Ashley facility. The plant faced local opposition. And Brightmark was counting on about $500 million in bonds from the Macon-Bibb County Industrial Authority, but the deal stipulated that Brightmark get the Ashley plant going, and the county pulled its support after determining that the company hadn’t succeeded in Indiana.

Powell says Brightmark was treated unfairly. “These are questions that I think with a tour of the facility that folks could have had answers to pretty quickly,” he says.

Brightmark, an early mover in pyrolysis, has also had to contend with evolving market demands, according to Powell. When the company started building its facility in 2019, the main concern was diverting plastics from the waste stream. Naphtha and diesel output was earmarked for the fuel market.

“In the intervening 3 years, the demand for fully circular plastics has exponentially grown,” he says. Now Brightmark aims to sell naphtha to chemical companies as a plastics raw material and wants to see its diesel end up in chemical markets as well.

Because of this increased demand for recycled feedstock, Nexus Circular is getting a lot of attention from big petrochemical makers. The company’s plant in Atlanta has 13,000 t of annual capacity. About 80% of its output is what Hartz describes as a mix of naphtha, gasoline, diesel, and heavier waxes. The rest is gases that Nexus uses for heat.

Shell and Chevron Phillips Chemical are already using output from the Nexus plant in their US petrochemical crackers. Dow has agreed to take the output from a plant in Dallas that will be twice the size of the Atlanta plant. Nexus also aims to build a 30,000 t unit in Chicago that will supply Braskem, one of its investors.

Hartz says one thing that sets his company apart is that it can handle different forms of plastics, such as usually hard-to-recycle films, with limited presorting. Nor does it need to process its output with distillation or hydrotreating, which he says “adds tremendous costs” as well as environmental burden.

Hartz happily concedes Dell’s point that Nexus is persnickety about the waste plastics it consumes. To avoid sorting and postprocessing, the firm does focus on acquiring relatively homogeneous polyolefin streams, like pallet wrap from retailers. While these materials might not fit everyone’s idea of postconsumer plastics, Hartz says, they were still destined for the landfill.

Nexus pays a premium for such plastics versus mixed household waste. “They’re not free if you want the right quality,” Hartz says. “If you want garbage, then you’re going to have to set up a very, very expensive process before you can even use it.”

Readying for pyrolysis

Many other companies are taking that approach and attempting to procure more mixed waste. “If you talk about true circularity going forward at scale, you are talking about mixed plastic waste; you are not talking about presorted polyolefins,” says Artem Vityuk, a global market manager at BASF. “You are really trying to expand the base of feedstock, and you need to be able to work with really contaminated feed.”

That means the output of pyrolysis units that consume a broad array of plastics must be upgraded to eliminate contamination. BASF recently introduced a new portfolio, called PuriCycle, of catalysts and adsorbents that eliminate such contaminants. The portfolio targets pyrolysis plants trying to meet customer specifications and petrochemical companies that want to clean feedstock coming from multiple sources.

Vityuk explains that contaminants such as halogens, oxygen, nitrogen, and metals are all found in the hydrocarbons coming out of pyrolysis plants. “That is what is in the plastics,” he says.

These contaminants can be nettlesome. An ethylene cracker might tolerate only 1 ppm of chlorine in its feed, so even one piece of PVC pipe in a pyrolysis reactor’s daily delivery can cause problems for a chemical company customer. BASF offers adsorbents to soak up the chlorine compounds. The product line also includes adsorbents and prehydrogenation catalysts marketed as being able to filter out particulate matter and eliminate the most reactive compouinds from the feedstock stream.

BASF also offers hydroprocessing catalysts similar to those that oil refineries use to displace sulfur with hydrogen. “We actually optimized the catalyst to make sure it’s suited for service in plastic pyrolysis oils,” Vityuk says. “It’s not a copy and paste from the refining area.” For example, rather than focusing on sulfur, the catalysts help remove nitrogen, which is in plastics such as nylon.

Steve Deutsch, a consultant with the Catalyst Group, says pyrolysis oil variability is an issue that the industry will need to tackle. While there are standards for ethylene cracker raw materials, “there’s nothing similar for pyrolysis oil,” he says. “The industry needs to evolve in such a way that it becomes more standardized.”

Petrochemical companies are starting to build infrastructure to process the products of pyrolysis plants. Shell is constructing upgraders at its chemical complexes in Moerdijk, the Netherlands, and Singapore to remove contaminants from pyrolysis oil sourced from third parties. Each will be capable of handling 50,000 t of oil per year.

“Due to the nascent stage of the chemical recycling industry, we can expect a large variation in the quality of the pyrolysis oil, whereby the upgrading step becomes integral in increasing usable quantities,” says Philip Turley, global general manager for plastics circularity at Shell.

Shell has already locked up supplies from various firms that might be able to supply the upgraders with pyrolysis oil. For instance, it has invested in BlueAlp, and the two plan to build 30,000 t per year of plastics pyrolysis capacity in the Netherlands. Shell also has an offtake agreement with Pryme, another European pyrolysis company.

Similarly, Dow is working with the engineering firm Topsoe to build a purification unit for pyrolysis oil at its complex in Terneuzen, the Netherlands. Like Shell, Dow says its unit is meant to purify and homogenize feedstocks that come from a variety of pyrolysis plants. “Some have a feedstock that still needs cleaning or processing before you can put it into a cracker. Some we can’t even look at,” Lahoti says, pointing to those with a high aromatic and naphthalene content.

“When you go from the start-up phase, which is where a lot of these companies are, you start thinking about how these technologies fit in the chemical industry,” Lahoti says. “And this is where a company like Dow allows some of these start-ups to be successful because we bring our technology experience, our processing experience, and we kind of help pull some of these feeds into our system.”

The technology evolves

Lahoti says pyrolysis processes themselves are evolving to better suit the petrochemical industry. He sees “a transition away from conventional pyrolysis to different technologies, some of which were built on conventional pyrolysis as a foundation but have advanced to a point where it’s not just pyrolysis.”

For instance, Lahoti doesn’t consider Mura’s technology to be pyrolysis. The key development is supercritical steam, which transfers heat directly to the polymer particles. In ordinary pyrolysis, heat comes from the kiln and is transferred by poorly conductive plastic particles. “The bigger you make the kiln, the harder it gets for that heat to get in there,” Lahoti says.

Firms are also introducing catalysis into the pyrolysis reactors themselves. In addition to lowering the activation energy of the process, catalysts can tune the output to more desirable products. After pyrolysis, you’re left with some molecules with 40 or 50 carbons—too big to feed to a cracker directly, the Catalyst Group’s Deutsch says. “With catalytic pyrolysis, you can make that distribution both narrower and toward the lighter end.”

Since 2020, LyondellBasell has been running a pilot plant in Ferrara, Italy, to test its catalytic pyrolysis technology, called MoReTec. While the company hasn’t said what catalysts it is testing, many pyrolysis research groups are working with zeolite catalysts, such as ZSM-5, that are commonly used in refining.

A sure sign that interest in pyrolysis is taking off is that large engineering companies are licensing technologies to third parties that want to get into the business. KBR is licensing Mura’s process. Lummus Technology is marketing a technology from New Hope Energy. And late last year, Honeywell UOP unveiled its own process, called UpCycle.

Kevin Quast, global business lead for Honeywell’s plastics circularity business, says Honeywell UOP’s reputation is a big help in the marketplace. “People like the UOP name,” he says. The firm “is very familiar with these types of technologies and is able to take something from pilot scale to a commercial scale.”

UOP bought the rights to a process that had been running in Europe for several years in the 1990s. The company has been piloting and refining it for 2½ years.

Quast notes some key differences between UpCycle and other pyrolysis systems. For instance, Honeywell UOP has a pretreatment step in which it selects the right plastics for the system and melts them down before they go into the main reactor. What comes out is a light fraction, like naphtha and diesel, as well as a heavier cut. The heavier stream can be sent to a fluidized catalytic cracker to make propylene.

Honeywell UOP is forming two joint ventures, one in Spain with the infrastructure firm Sacyr and another in Texas with the recycler Avangard Innovative. Honeywell UOP is also licensing the process for plants in China and Turkey.

The scale of the Honeywell UOP plants—30,000 t per year—is a “sweet spot” for the amount of feedstock that can be gathered in a midsize city, Quast says. He questions whether some of the larger pyrolysis plants that have been announced will be able to acquire feedstocks economically.

Another sign that pyrolysis is hitting the big time is that one of the world’s largest oil companies, ExxonMobil, is making a push. Next month, the company will complete a pyrolysis facility at its petrochemical complex in Baytown, Texas, with the capacity to process 30,000 t of plastics per year.

“We’re actually processing the plastic waste directly in our own facility,” says Natalie Martinez, feed-to-value business manager at ExxonMobil. She declines to provide more detail about the equipment being used or the postprocessing involved.

Colocating plastics pyrolysis at a petrochemical complex allows ExxonMobil to use gases that stand-alone systems have to consume for fuel, Martinez says. “Everything that is coming out of the process is being utilized in an integrated facility,” she says.

ExxonMobil has a joint venture with the pyrolysis firm Agilyx, called Cyclyx International, that is dedicated to finding feedstock for the plant. ExxonMobil is exploring optical sorting and advanced analytics to manage the large amounts of material that will be headed there. “You can’t support that with hand sortation,” Martinez says.

If a large oil and chemical company like ExxonMobil can operate the process successfully at large scale, it will be the ultimate refutation of pyrolysis naysayers. The company aims to roll out the technology at plants around the world to reach a goal of recycling 500,000 tons of plastics annually by the end of 2026.

“We know that scale, and being able to do this globally, is really going to be the key to ultimate success,” Martinez says. “It’s not just the technical aspects of processing plastic waste. We know that’s achievable and doable. It’s scale that will be meaningful and providing a solution to society.”

Carpets pollute Aussie homes with plastic

Australians have been urged to reconsider carpeting their homes after a study found the floor covering may double microplastic pollution in household dust.Scientists from Macquarie University gathered and analysed dust samples from 108 households across 29 countries, including about 30 homes in Australia.Overall, dust from carpeted homes had roughly twice the microplastics load than dust from homes with other types of flooring.Dr Neda Sharifi-Soltani led the research and said the scientific community was still trying to understand how microplastics might impact human health.Separate studies have detected microplastics in human faeces, urine, blood and in people’s lungs, with research ramping up globally into potential effects.The dust study found that even though some of the microplastics polymers detected were toxic, the exposure dose was low.But Dr Sharifi-Soltani also warned: “This is an underestimation because of all the knowledge gaps and analytical instrument limitations that we encountered.”Doing the health risk assessment for microplastics in household dust is in its early stages.”In her mind the findings so far are enough to warrant a warning for people to reconsider installing carpets in their homes.The study was based on indoor atmospheric dust samples gathered over a one-month period from 108 homes in 29 high, medium and low-income countries.The 16 high-income countries included Australia, the United States, Canada, France, Germany, New Zealand, Singapore and Switzerland.”Australia had the second-highest amount of microplastics in household dust among higher-income countries,” Dr Sharifi-Soltani said.The dust analysis was informed by a range of other information gathered from study participants, including flooring type, how often floors were cleaned, and how many people lived in each home.In all countries, greater vacuuming frequency was associated with lower microplastics loads.Story continuesLower-income countries had higher loads of microplastics, which were deposited at an average daily rate of 3,518 fibres per square metre, per day.The rates for medium-income and high-income countries were 1,268 and 1,257 respectively.”No matter what country we collected the dust from, the single biggest influence on the amount of microplastics in household dust was … how often the floors were vacuumed,” she said.The study also showed most of the microplastics found in household dust came from sources inside the home, not outside.The research has been published in the journal Environmental Pollution.

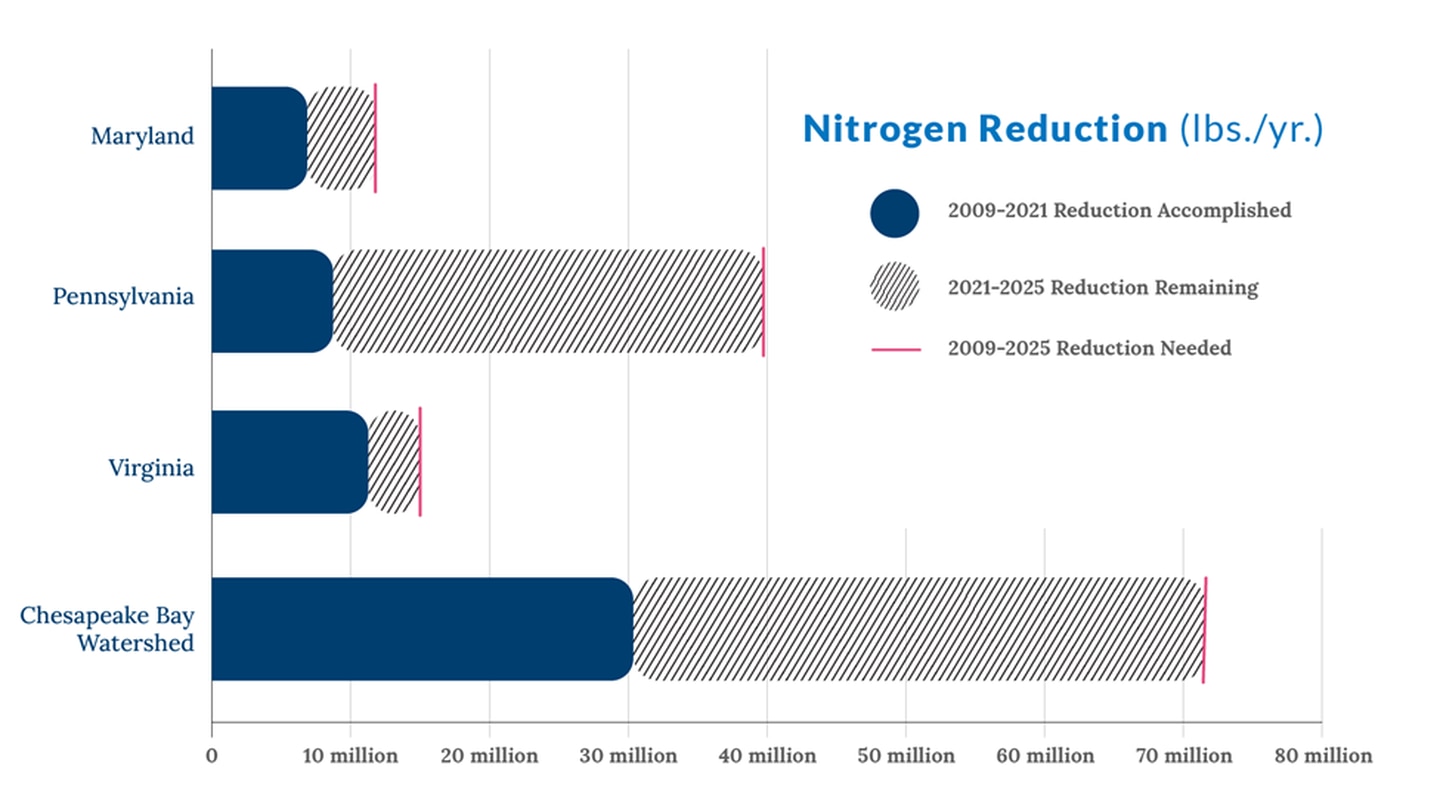

Voters care about pollution, so why is the Chesapeake Bay dirty?

A majority of Virginia voters are concerned about pollution, particularly plastics clogging waterways and runoff that contaminates waters, according to a recent survey by the Virginia Coastal Zone Management Program, Clean Virginia Waterways at Longwood University and OpinionWorks. Most voters also support legislation to cut pollution.Steve Raabe, founder and president of OpinionWorks, also said that he was surprised that while 87% of respondents called water pollution a serious problem, most didn’t realize that it comes from people discarding plastic bottles, tires, food containers and more on land.AdvertisementWhen the respondents think of ocean debris, he said, they assumed it came from fishermen dumping trash.According to the study, 87% of the 901 surveyed said plastic in the water is at least a “somewhat-serious” problem, while 65% of people said land litter was at least a “somewhat-serious” problem. Nearly 80% said they are most concerned about harmful chemicals and toxins in water.AdvertisementThe Chesapeake Bay Foundation on Wednesday released its 2022 State of the Blueprint report, which found Virginia, along with Maryland and Pennsylvania, are not on track to meet their pollution reduction goals in lowering nitrogen, phosphorous and sediment levels.Chesapeake Bay Foundation graph on how nitrogen reduction progress by state. Hilary Falk, the Chesapeake Bay Foundation director, wants the states to recommit to the blueprint.Virginia has improved in areas such as wastewater mitigation — meaning waste water treatment facilities are performing better because of infrastructure upgrades. The report states the commonwealth has a chance to get back on track because of these improvements but lags in decreasing in the amount of runoff.“That approach is not sustainable,” said CBF Virginia Executive Director, Peggy Sanner. “About 90% of Virginia’s remaining pollution reductions must come from agriculture, and population growth and climate change are leading to more polluted runoff from developed areas.”According to Chris Moore, a CBF senior regional ecosystem scientist, pollutants such as nitrogen attaches to plastics. Fish eat the debris and get sick.“Unfortunately, a lot of our plastic pollution that gets into our waterways comes from runoff,” Moore said. “It’s stuff that gets discarded on streets or maybe blows out of someone’s car, blows off someone’s lawn, eventually gets swept up in stormwater.”Earlier this year, the Virginia Best Management Practices program, which helps control farm and urban runoff, received historic funding of $295 million over the next two years. It uses a cost-share program that helps farmers pay for fences to go around bodies of water and prevent livestock from entering and contaminating the runoff.However, according to Sanner, such investments may not be enough.AdvertisementToday’s Top StoriesDailyStart your morning in-the-know with the day’s top stories.There is a possibility that the 2025 blueprint deadline will be pushed back, but CBF and state officials will discuss how to stick as close to the original deadline as possible. Problems like inflation, which increases costs, and the need for more funding are barriers to meeting the 2025 pollution goals.The voter survey included interviews conducted in March among residents across political parties, ethnic, racial and gender lines. Raabe said the survey was statistically representative of the state with a 3.3% margin of error.It showed the participants support legislation to help prevent litter: 61% support a ban on single-use plastic bags; the majority also supported banning plastic straws and polystyrene (plastic foam). Less than half — 41% — were in favor of a 5-cent tax for using grocery store plastic bags.Percentage of participants who want to ban single-use plastic bags. Legislation calling for phasing out plastic foam containers has been pushed back this year and Gov. Glenn Youngkin released an executive order in April that repealed a plastic bottle ban among state agencies.According to Raabe, many shoppers forget to use reusable bags, even when they keep them in their cars. But, stores, he said, could display signs reminding people to grab them before coming in.Also in the survey, 23% of the participants said they chose bottled water instead of tap water, even in areas where the tap water is considered safe. Nearly 40% said they drink bottled water often.AdvertisementEverett Eaton, 262-902-7896, everett.eaton@virginiamedia.com

Indonesian program pays fishers to collect plastic trash at sea

The Indonesian fisheries ministry has launched a four-week program to pay fishers to collect plastic trash from the sea.The initiative is part of wider efforts to reduce Indonesia’s marine plastic pollution by 70% by 2025.The country is a top contributor to the plastic trash crisis in the ocean.Each of the 1,721 participating fishers will receive the equivalent of $10 a week for collecting up to 4 kg (9 lbs) of plastic waste from the sea daily. JAKARTA — The Indonesian government has launched a program that will pay thousands of traditional fishers to collect plastic trash from the sea. The four-week initiative is part of wider efforts to cut marine plastic waste by 70% by 2025.

The Ministry of Marine Affairs and Fisheries said on Oct. 4 that it had budgeted 1.03 billion rupiah ($67,600) to pay 1,721 fishers across the archipelago for any plastic trash they collected daily from Oct. 1-26. It said the money, which works out to about 150,000 rupiah ($10) per fisher per week, would serve as compensation for their not fishing during this period. That’s slightly more than the 140,000 rupiah ($9) per week that the ministry estimates they earn from fishing.

“This activity is very simple,” Sakti Wahyu Trenggono, the fisheries minister, said at a press conference in Jakarta, adding that it wasn’t expected to be the silver bullet for the country’s marine waste problem. “But at least this will raise awareness among the stakeholders at sea and the people around the world.”

A manta ray swimming amid plastic trash in Indonesian waters. Image courtesy of Elitza Germanov.

The fisheries ministry says it expects each fisher to collect up to 4 kilograms (9 pounds) of plastic trash daily during the program. Participants are located across all of Indonesia’s main islands.

Indonesia is one of the largest contributors to marine plastic pollution in the world. The country produces about 6.8 million metric tons of plastic waste annually, according to a 2017 survey by the Indonesia National Plastic Action Partnership. Only 10% of that waste is processed in the approximately 1,300 recycling centers in the country, while nearly the same amount, about 620,000 metric tons, winds up in the ocean.

Marine plastic waste poses a threat to marine animals, who can become entangled in it or ingest it. This leads to suffocation, starvation, or drowning. Marine plastics have been blamed for the deaths of more than 100,000 marine mammals annually. If the dumping of plastic in the oceans continues at current rates, by 2050 it will outweigh all fish biomass, according to an estimate.

“The most important thing is prevention,” Sakti said. “If we can properly conduct prevention, then there shouldn’t be any waste in the sea. Because once the trash gets to the sea, then it’s already damaged.”

Plastic pollution is rampant in Indonesian ports. Image by Anton Wisuda/Mongabay Indonesia.

Indonesia plans to spend $1 billion to cut 70% of its plastic waste by 2025. Proper management of plastic waste is lacking in coastal communities, where the use of plastics far outpaces mitigation efforts such as recycling.

Beach cleanups are among the popular measures being carried out here. Local governments are also implementing efforts to reduce the consumption of single-use plastics, including outright bans, while the private sector is investing in sustainable alternatives. The government also plans to make producers take greater responsibility for the waste generated by their products.

“This is an important moral message to the world that dumping plastic waste into the sea is very bad,” Sakti said. “Hopefully this can be a nationwide effort and, even better, a worldwide action.”

Plastic trash on Kuta Beach, one of the main tourist destinations on the Indonesian island of Bali. Image by Luh De Suriyani/Mongabay Indonesia.

Basten Gokkon is a senior staff writer for Indonesia at Mongabay. Find him on Twitter @bgokkon.

FEEDBACK: Use this form to send a message to the author of this post. If you want to post a public comment, you can do that at the bottom of the page.

Conservation, Corporations, Environment, Environmental Law, Environmental Policy, Environmental Politics, Fish, Fisheries, Food Waste, Marine, Marine Conservation, Marine Crisis, Marine Ecosystems, Microplastics, Ocean Crisis, Oceans, Plastic, Pollution, Sustainability, Waste, Water Pollution

Print

Study links in utero ‘forever chemical’ exposure to low sperm count and mobility

Study links in utero ‘forever chemical’ exposure to low sperm count and mobilityPFAS, now found in nearly all umbilical cord blood around the world, interfere with hormones crucial to testicle development A new peer-reviewed Danish study finds that a mother’s exposure to toxic PFAS “forever chemicals” during early pregnancy can lead to lower sperm count and quality later in her child’s life.PFAS – per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances – are known to disrupt hormones and fetal development, and future “reproductive capacity” is largely defined as testicles develop in utero during the first trimester of a pregnancy, said study co-author Sandra Søgaard Tøttenborg of the Copenhagen University Hospital.TopicsFertility problemsHealthPollutionPlasticsMen’s healthPregnancynewsReuse this content

COP27: Activists 'baffled' that Coca-Cola will be sponsor

HECTOR RETAMALBy Esme StallardBBC News Climate and ScienceClimate activists are “baffled” over Egypt’s decision to have Coca-Cola – a major plastic producer – sponsor this year’s global climate talks.Campaigners told the BBC the deal undermines the talks, as the majority of plastics are made from fossil fuels. Coca-Cola said it “shares the goal of eliminating waste and appreciates efforts to raise awareness”.This year’s COP27 UN climate talks are hosted by the Egyptian government in November in Sharm el-Sheikh.Egypt announced it had signed the sponsorship deal last week.At the signing, Coca-Cola Global Vice-President, Public Policy and Sustainability Michael Goltzman said: “Through the COP27 partnership, the Coca-Cola system aims to support collective action against climate change.”But opposition to the decision has grown over the past week over Coca-Cola’s links to plastic pollution. Climate activists are accusing the company of “greenwashing” and more than 5,000 have now signed a petition calling for the decision to be reversed. The company admitted in 2019 that it uses three million tonnes of plastic packaging in a year. Found on every continent and in the oceans, plastic is a major source of pollution. Its production also contributes to global warming. Currently 99% of global plastic is produced from fossil fuels in a process called ‘cracking’ which produces greenhouse gas emissions and drives climate change. And in 2021, an audit from Break Free From Plastic named Coca-Cola as the world’s number one plastic polluter.Mohammad Ahmadi of Earth Uprising International said: “This action by the COP27 presidency goes against the purpose of the conference.”This was a sentiment echoed by Steve Trent, CEO of the Environmental Justice Foundation, who called on Egypt to reverse the decision. Neither Egypt’s COP27 presidency nor UNFCCC – the UN’s climate change body – responded to the BBC’s request for comment on the sponsorship deal. Last year when the UK government hosted the climate talks, they banned fossil fuel companies from sponsoring the event.Mr Trent said: “Coca-Cola’s whole business model is predicated on fossil fuels. They have made promises to improve recycling which have never been met.”NurPhoto/Getty ImagesCoca-Cola told the BBC it recognised it needs to do more: “While we have made progress against our World Without Waste goals, we’re also committed to do more, faster.”Climate activists the BBC spoke to were not only concerned about the signal the sponsorship sent, but also how it could affect the negotiations. Nyombi Morris, a climate activist from Uganda and a UNOCHA Ambassador, told the BBC: “When polluters dominate climate negotiations, we don’t get good results. As an African activist, I am concerned that more of our lakes are going to be filled with plastics again.”Last year the BBC revealed the impact that plastic pollution by Coca-Cola was having on remote communities across the world.This video can not be playedTo play this video you need to enable JavaScript in your browser.Coca-Cola told the BBC that it remains committed to: “collect and recycle a bottle or can for every one we sell by 2030.”

'Humble' worm saliva can break down tough plastic

SPLBy Matt McGrathEnvironment correspondentOne of the worst forms of plastic pollution may have met its match in the saliva of a humble worm.Spanish researchers say they’ve discovered chemicals in the wax worm’s drool that break down polyethylene, a tough and durable material.The researchers say that one hour’s exposure to the saliva degrades the plastic as much as years of weathering.They hope the breakthrough will lead to new natural approaches to deal with plastic pollution.They’ve discovered two enzymes in the liquid that can degrade polyethylene at room temperatures and believe it’s the first time that such an effective agent has been found in nature. King will not attend climate summit on Truss advicePoorer homes to get £1.5bn energy efficiency helpInvestment zones ‘unprecedented attack on nature’From the poles to the depths of the oceans, plastic is a major pollution issue across the whole world.Getty ImagesWhile efforts to reduce, recycle and reuse plastic are slowly making progress, there are few options when it comes to the very sturdy polyethylene (PE) material. It is one of the most widely used forms, comprising around 30% of production and is used for a wide range of materials including hard wearing items like pipes, flooring, and bottles but it’s also used for bags and food containers. This plastic is dense and is very slow to break down in nature as it is highly resistant to oxygen. Most attempts to degrade it require PE to be pre-treated with heat or UV light to incorporate oxygen into the polymer. Getty ImagesThe Spanish team first discovered that wax worms could break down the material in 2017, but in this new study they’ve worked out that the key elements are enzymes in the creature’s saliva. In their paper they show that this key step of getting oxygen into the polymer can be achieved within an hour of the plastic being exposed to the saliva of the larvae. “What we think is that the enzymes are capable of an accelerated version of the weathering of polyethylene,” said Dr Clemente Arias, a co-author from the Spanish National Research Council. “What we found was that the enzymes alone can oxidise plastic, which is the process that takes such a long time in the environment,” he told BBC News. The researchers are using saliva from the larvae of the greater wax moth, commonly known as wax worms. SPLThese creatures are a well known pest that attacks and destroys honeybee hives. They are also popular with anglers as a bait and as a food source for reptiles. The researchers say the larvae’s destructive abilities when it comes to beeswax may provide an explanation of their capacity for PE degradation. The scientists believe that what they’ve discovered so far provides a promising alternative approach to biological degradation and could lead to new solutions.”We imagine you could apply this new understanding to large plastic waste management facilities,” said Dr Federica Bertocchini, a co-author on the paper also from the Spanish National Research Council. “But you could also have a home-based kit which could help you degrade your own plastic.”There are still many questions to be answered, say the researchers, including whether the saliva is working on the polymer or on the additives that are used to strengthen this type of plastic. “We also want to know why a humble worm has these amazing enzymes, what’s the use of them in their daily life,” said Dr Arias. They want to now develop their work by carrying out bigger experiments.”The field of biodegradation is focused on bacteria and fungi, mostly bacteria, and on looking for enzymes,” said Dr Bertocchini.”Now we have some enzymes that work, so the idea is, well, let’s give it a try.”The study has been published in the journal, Nature Communications. Follow Matt on Twitter @mattmcgrathbbc.

‘One more thing’ about plastics: They could be acidifying the ocean, study says

New research suggests that plastic could contribute to ocean acidification, especially in highly polluted coastal areas, through the release of organic chemical compounds and carbon dioxide, both of which can lower the pH of seawater.The study found that sunlight enabled this process and that older, degraded plastics released a higher amount of dissolved organic carbon and did more to lower the pH of seawater.However, the findings of this study were conducted in a laboratory, so it’s unclear whether experiments conducted in estuaries or the open ocean would yield similar results, experts said. The trillions of pieces of plastic currently roving through the global ocean are known to be an assault on life. Turtles get tangled up in discarded plastic fishing nets. Whales open their mouths to eat and unwittingly fill their stomachs with shopping bags. Filter-feeding fish and other organisms gobble up tiny plastic particles, poisoning themselves with the plastic’s toxins and passing that toxicity along to any animal that consumes them.

And now, new research suggests that plastic pollution could be harming the ocean in an additional way: by contributing to its acidification.

Through a series of laboratory experiments, scientists from the Marine Sciences Institute in Barcelona, known as ICM-CSIC by its Spanish acronym, found that when plastic — especially aged, degraded plastic — interacts with sunlight, it releases a cocktail of chemicals, including organic acids, into the ocean. Organic acids are known to lower the pH of seawater, causing it to become more acidic. In addition, the sun’s degradation of plastic can lead to carbon dioxide (CO2) release, which can cause pH to plummet further.

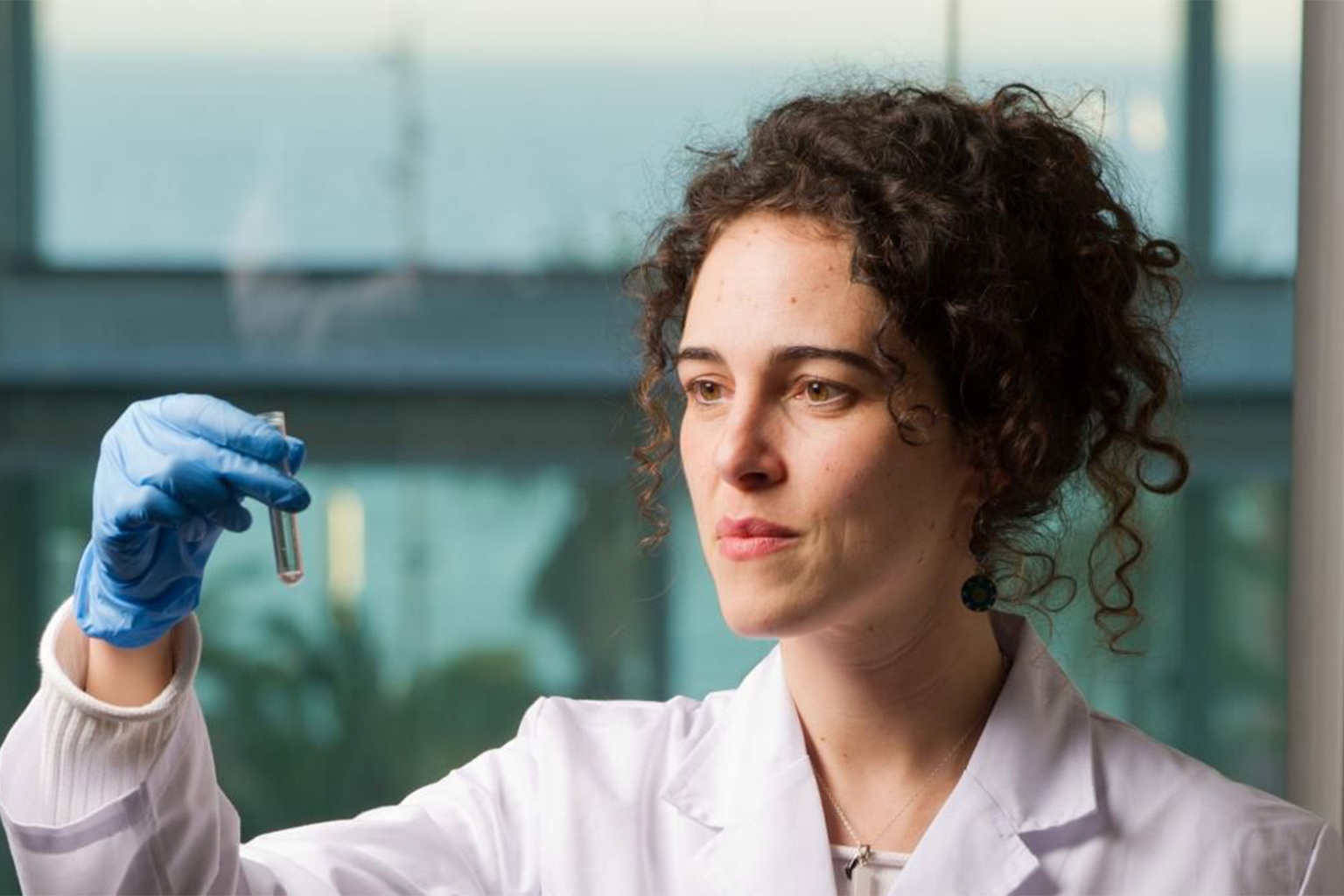

In highly polluted parts of the ocean, such as coastal areas, plastic could contribute to a drop of up to 0.5 pH units, which is “comparable to the pH drop estimated in the worst anthropogenic emissions scenarios for the end of the 21st century,” says Cristina Romera-Castillo, a postdoctoral researcher at ICM-CSIC and lead author of the study documenting the findings.

Lead author of the study Cristina Romera-Castillo examines a sample of polluted ocean water. Image courtesy of Marc Gasser.

“The main factor producing the acidification is the greenhouse gas emissions that are dissolved in the ocean,” Romera-Castillo told Mongabay. “But I think it’s interesting to know that plastic is also contributing to the acidification.”

The world’s oceans absorb about 30% of humanity’s carbon emissions, which has resulted in a decrease in pH across the globe. Lowered pH obstructs the ability of marine organisms, such as corals, planktons, oysters and urchins, to build skeletons and shells out of calcium carbonate and to generally survive. The weakening of these calcifying organisms can impact other species that depend on them for food and habitat.

Like other climate change impacts, ocean acidification doesn’t occur uniformly across the world’s seas. But it’s estimated that, on average, the pH of surface waters has fallen by about 0.1 pH units. That may not sound like a lot, but scientists say this drop has already resulted in numerous and widespread changes across the global ocean. And things are set to get much worse if greenhouse gas emissions continue to rise.

Some scientists even warn that ocean acidification represents a planetary boundary since it could significantly disrupt the functioning of Earth’s natural operating systems. According to the planetary boundaries theory, Earth’s ability to support life as we know it could be threatened if humanity pushes ocean acidification past a certain threshold — a limit beyond which the planet cannot cope with the changes and stresses humans place on it. When the impacts of high levels of ocean acidification interact with other Earth systems and processes, the resulting destabilization could place human life at risk.

Scientists found that when plastic — especially aged, degraded plastic — interacts with sunlight, it releases a cocktail of chemicals, including organic acids, into the ocean. Image courtesy of Cristina Romera-Castillo.

While plastic pollution would not have nearly as much of an impact on ocean acidification as greenhouse emissions would, Romera-Castillo said it’s something to keep an eye on.

“There are many reasons why we should be concerned about plastic, and this is one more thing,” Romera-Castillo said. “This is not the only one or maybe not the worst, but it’s one more thing.”

Romera-Castillo and her coauthors conducted their lab experiments with new plastics, as well as aged plastic collected from Canary Island beaches. They placed the plastic waste inside glass bottles filled with seawater, and then exposed the bottles to ultraviolet light similar to the amounts occurring in sunlight. They found that the older plastic released a higher amount of dissolved organic carbon and did more to lower the pH of the seawater.

Right now, nearly 13 million metric tons of plastic reach the ocean each year, but this number could increase dramatically in the near future. According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, plastic production could triple in the next 40 years, going from about 460 million metric tons in 2019 to 1.23 billion metric tons in 2060. More than likely, much of that plastic will end up in the natural environment, including the ocean. A UN plastics treaty which is currently in the works could potentially reduce those waste amounts.

Plastics, lumped in with roughly 350,000 other types of artificial chemicals in the global marketplace, are also categorized under another already breached planetary boundary. These so-called novel entities have become so pervasive as pollutants in the world — with new ones being engineered and introduced all the time — that they have violated the novel entity boundary’s critical threshold, with governments no longer able to keep up with evaluation or regulation of synthetic chemical risks.

Jason Hall-Spencer, a marine biologist and ocean acidification expert at the University of Plymouth, who was not involved in the new study, says the research shines a light on an important finding: that plastics do break down in seawater, releasing organic compounds and CO2 in the process.

“I think it’s important that people know about this phenomenon,” Hall-Spencer told Mongabay, “because what we’re often told is that plastics, once they get into the ocean, will last for millions of years, won’t break down or be there effectively forever.”

Right now, nearly 13 million metric tons of plastic reach the ocean each year, but this number could increase dramatically in the near future. Image by Naja Bertolt Jensen / Ocean Image Bank.

However, he questioned whether plastic would significantly contribute to acidification in the actual ocean. For instance, he suggested that waves and currents could mix the water and dissipate the impacts of plastic acidification. He also pointed out that ocean plastics are often encrusted with biological organisms that consume carbon dioxide and produce oxygen, which might also reduce the plastic’s contribution to acidification.

Furthermore, Hall-Spencer noted that a lot of ocean plastic ends up in places far from sunlight — like on the seafloor.

“It’s important that we know these plastics break down, and in doing so, they lower the pH,” he said. “But what’s needed as a next stage is verification that plastics in the ocean are lowering the pH.”

Stephen Widdicombe, a marine ecologist at Plymouth Marine Laboratory and co-chair of the Global Ocean Acidification Observing Network, who was also not involved in the new study, said the findings are noteworthy since they indicate that plastic could be a potential driver of ocean acidification in coastal regions. But like Hall-Spencer, he said more research would need to be done to understand if these processes would happen outside the lab in real world situations and on a larger scale.

The study “does show us the importance of monitoring for multiple threats,” Widdicombe told Mongabay. “Often we get fixated on thinking, ‘Oh, we’ve got to go and monitor how much plastic there is there,’ or ‘We’ve got to go and monitor for ocean warming or deoxygenation,’ when really what we should be monitoring for is everything.”

Romera-Castillo said it would be much harder to conduct the same experiments in the ocean due to the multiple factors one has to consider, such as the respiration of microorganisms and the movement of the water. However, she said she and her team would like to try this in the future.

“This [study] is the first step,” she said. “Now, there are many questions opening up.”

Banner image: A coral reef in Sharm el Sheikh, Egypt. Lowered pH obstructs the ability of marine organisms, such as corals, planktons, oysters and urchins, to build skeletons and shells out of calcium carbonate and to generally survive. Image by Renata Romeo / Ocean Image Bank.

Citations:

Romera-Castillo, C., Lucas, A., Mallenco-Fornies, R., Briones-Rizo, M., Calvo, E., & Pelejero, C. (2023). Abiotic plastic leaching contributes to ocean acidification. Science of The Total Environment, 854, 158683. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.158683

Persson, L., Carney Almroth, B. M., Collins, C. D., Cornell, S., De Wit, C. A., Diamond, M. L., … Hauschild, M. Z. (2022). Outside the safe operating space of the planetary boundary for novel entities. Environmental Science & Technology. doi:10.1021/acs.est.1c04158

Rockström, J., Steffen, W., Noone, K., Persson, Å., Chapin III, F. S., Lambin, E., … Foley, J. (2009). Planetary boundaries: Exploring the safe operating space for humanity. Ecology and Society, 14(2). Retrieved from https://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol14/iss2/art32/

Elizabeth Claire Alberts is a staff writer for Mongabay. Follow her on Twitter @ECAlberts.

FEEDBACK: Use this form to send a message to the author of this post. If you want to post a public comment, you can do that at the bottom of the page.

Chemicals, Coastal Ecosystems, Environment, Fish, Marine, Marine Biodiversity, Marine Conservation, Marine Crisis, Marine Ecosystems, Microplastics, Ocean Acidification, Ocean Crisis, Oceans, Plastic, Pollution, Research

Print