Credit: MarkPiovesan/Getty Images

Plastic pollution is an escalating global problem. Australia now produces 2.5 million tonnes of plastic waste each year, while world-wide production is expected to double by 2040.

This pollution doesn’t just accumulate on our beaches: it can be found on land and other marine environments (heard of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch?)

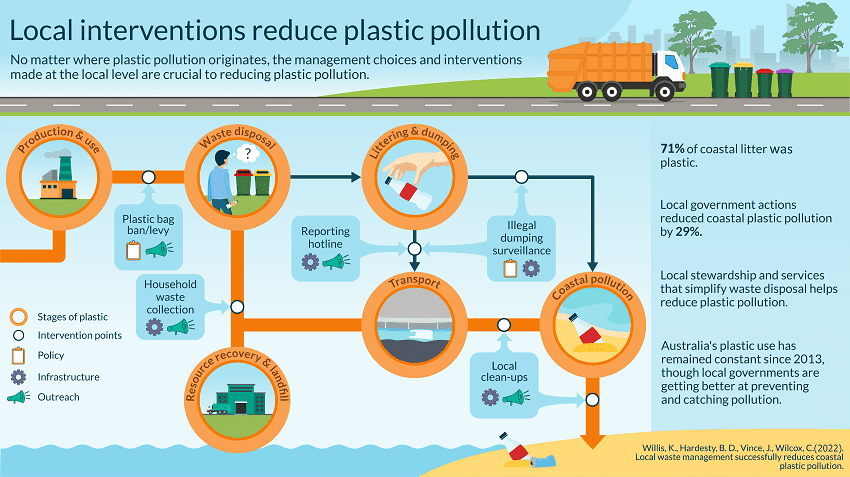

But according to a new study by Australia’s national science agency, CSIRO, plastic pollution on Australia’s coasts has decreased by 29% since 2013.

The study, which assessed waste reduction efforts in Australia and their effect on coastal pollution, highlights that although Australia’s plastic use has remained constant since 2013, local governments are getting better at preventing and cleaning up pollution.

“Our research set out to identify the local government approaches that have been most effective in reducing coastal plastics and identify the underlying behaviours that can lead to the greatest reduction in plastic pollution,” says lead researcher Dr Kathryn Willis, a recent PhD graduate from the University of Tasmania.

“Whilst plastic pollution is still a global crisis and we still have a long way to go, this research shows that decisions made on the ground, at local management levels, are crucial for the successful reduction of coastal plastic pollution,” she adds.

The study has been published in One Earth.

Local government approaches work

The new research builds upon extensive 2013 CSIRO coastal litter surveys with 563 new surveys and interviews with waste managers across 32 local governments around Australia completed in 2019.

The results found that, although there was a decrease in the overall national average coastal pollution by 29%, some surveyed municipalities showed an increase in local litter by up to 93%, while others decreased by up to 73%.

Since global plastic pollution is driven by waste reduction strategies at a local level (regardless of where the pollution originates), researchers then focused on identifying which local government approaches had the greatest effect on these levels of coastal pollution.

Get an update of science stories delivered straight to your inbox.

To do this they sorted local government waste management actions into three categories of human behaviour, including:

Planned behaviour – strategies like recycling guides, information and education programs, and voluntary clean-up initiatives.Crime prevention – waste management strategies like illegal dumping surveillance and beach cleaning by local governments.Economic – actions like kerb-side waste and recycling collection, hard waste collections and shopping bag bans.

Graphical abstract ofthe study. Credit: Willis et al (2022) DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oneear.2022.05.008

They found that retaining and maintaining efforts in economic waste management strategies had the largest effect on reducing coastal litter.

“For example, household collection services, where there are multiple waste and recycling streams, makes it easier for community members to separate and discard their waste appropriately,” says co-author Dr Denise Hardesty, a principal research scientist at CSIRO Oceans and Atmosphere.

“Our research showed that increases in waste levies had the second largest effect on decreases in coastal plastic pollution. Local governments are moving away from a collect and dump mindset to a sort and improve approach,” adds Hardesty.

Clean-up activities, such as Clean Up Australia Day, and surveillance programs that directly involved members of the community were also effective.

“Increasing community stewardship of the local environment and beaches has huge benefits. Not only does our coastline become cleaner, but people are more inclined to look out for bad behaviour, even using dumping hotlines to report illegal polluting activity,” says Hardesty.

Another piece of the solution to our plastics problem

This isn’t the be-all and end-all solution to Australia’s plastics problem – let alone globally – but this research does provide decision-makers with empirical evidence that the choices made by municipal waste managers and policymakers are linked to reductions in plastic pollution in the environment.

Identifying the most effective approaches for reducing coastal litter is an important part of future plastic pollution reduction strategies. The CSIRO’s Ending Plastic Waste Mission is aiming for an 80% reduction in plastic waste entering the Australian environment by 2030.

“While we still have a long way to go, and the technical challenges are enormous, these early results show that when we each play to our individual strengths, from community groups, industry, government and research organisations, and we take the field as Team Australia, then we can win,” says Dr Larry Marshall, chief executive of CSIRO.