PhilippinesPhotos show Manila Bay mangroves ‘choking’ in plastic pollutionThe Navotas mudflats are among the last of their kind and act as a crucial feeding ground for migratory birds, but they are being buried in plastic Rebecca Ratcliffe, south-east Asia correspondentMon 4 Oct 2021 20.13 EDTLast modified on Tue 5 Oct 2021 15.22 EDTThere are stray, abandoned flip flops, old foil food wrappers, crumpled plastic bags, and discarded water bottles. The Navotas mudflats and mangroves in Manila Bay are buried in a thick layer of rubbish.It is “almost choking the mangrove roots,” Diuvs de Jesus, a marine biologist in the Philippines who photographed the area on a recent visit, said.The wetlands are of huge environmental significance. They provide a crucial feeding ground for migratory birds, offer protection against floodwater and help tackle climate change by absorbing far greater levels of carbon dioxide than mountain forests.The plastic pollution, though, could devastate the area. Mangroves have special roots, known as pneumatophores, “sort of like a snorkel that helps them breathe in when sea water rises,” says Janina Castro, member of the Wild Bird Club of the Philippines and advocate for wetland conservation. Plastic risks suffocating pneumatophores, weakening, and potentially killing the trees.’The odour of burning wakes us’: inside the Philippines’ Plastic CityRead moreThe mudflats and mangroves are already one of the last of their kind in Manila Bay, an area that was once lined with lush, green shrubs and trees. Manila is thought to have been named after the Nilad, a stalky rice plant that grows white flowers, and which once thrived along the coastline. At the end of the 19th century, there were up to 54,000 hectares of mangrove wetlands along the bay, according to an estimate cited by Pemsea, a regional, marine protection partnership coordinated by the United Nations. By 1995 this had fallen to fewer than 800 hectares.Today, Manila, one of the most densely populated cities in the world, is more likely to be associated with traffic jams than flourishing mangroves.“If only we banned single-use plastics, that will greatly reduce the litter,” De Jesus said. He worries also about the looming threat of reclamation – where coastlines are extended outwards as rock, cement and earth are used to build new land in the sea.The Navotas mangroves and mudflats are vital to the survival of migratory birds that visit the Philippines as part of the east Asian-Australasian flyway – a route that stretches from Arctic Russia and North America down to Australia and New Zealand.A number of endangered birds have been spotted feeding and resting in the wetlands, including the black-faced spoonbill, the far eastern curlew, and the great knot. The critically endangered Christmas Island frigatebird was also recently seen flying low over Navotas, Castro says.Environmentalists fear plastic pollution could ultimately harm such species. It breaks down into microplastics, which can be eaten by fish and shellfish – and, consequently, also be ingested by birds. It can also lead to an accumulation of toxic chemicals, and act as a vector for disease, threatening birds and their prey, Castro said.“A number of these species currently have conservation efforts happening in other countries, but these efforts need to be mirrored in all of the staging sites including the Philippines,” Castro said.There is a misconception that mudflats are not as valuable or aesthetically pleasing as other types of wetlands, Castro said. But they play an important role in tourism, providing livelihoods and offering wave protection. “Educating the public about these benefits is critical for its survival,” she said.TopicsPhilippinesAsia PacificPollutionfeaturesReuse this content

Author Archives: David Evans

India to ban single-use plastics but experts say more must be done

Following the Indian government’s announcement banning various low-utility plastics, experts outline a list of structural issues that need to be addressed for the ban to be effective.

Research and development into alternatives along with guidelines for their efficient use are needed.

A lack of quality recycling and waste segregation also need to be addressed to improve the percentage of plastic that is recycled.

A cyclist uses a plastic sheet to protect himself from rain, at sector 27, on August 1, 2021 in Noida, India.

Sunil Ghosh | Hindustan Times | Getty Images

India will ban most single-use plastics by next year as part of its efforts to reduce pollution — but experts say the move is only a first step to mitigate the environmental impact.

India’s central government announced the ban in August this year, following its 2019 resolution to address plastic pollution in the country. The ban on most single-use plastics will take effect from July 1, 2022.

Enforcement is key for the ban to be effective, environmental activists told CNBC. New Delhi also needs to address important structural issues such as policies to regulate the use of plastic alternatives, improve recycling and have better waste segregation management, they said.

Single-use plastics refer to disposable items like grocery bags, food packaging, bottles and straws that are used only once before they are thrown away, or sometimes recycled.

“They have to strengthen their systems in the ground to ensure compliance, ensure that there is an enforcement of this notification across the industry and across various stakeholders,” Swati Singh Sambyal, a New Delhi-based independent waste management expert told CNBC.

Why plastics?

As plastic is cheap, lightweight and easy to produce, it has led to a production boom over the last century, and the trend is expected to continue in the coming decades, according to the United Nations.

But countries are now struggling with managing the amount of plastic waste they have generated.

About 60% of plastic waste in India is collected — that means the remaining 40% or 10,376 tons remain uncollected, according to Anoop Srivastava, director of Foundation for Campaign Against Plastic Pollution, a non-profit organization advocating for policy changes to tackle plastic waste in India.

Independent waste-pickers typically collect plastic waste from households or landfills to sell them at recycling centers or plastic manufacturers for a small fee.

However, a lot of the plastics used in India have low economic value and are not collected for recycling, according to Suneel Pandey, director of environment and waste management at The Energy and Resources Institute (Teri) in New Delhi.

In turn, they become a common source of air and water pollution, he told CNBC.

Banning plastics is not enough

Countries, including India, are taking steps to reduce plastic use by promoting the use of biodegradable alternatives that are relatively less harmful to the environment.

For example, food vendors, restaurant chains and some local businesses have started adopting biodegradable cutlery and cloth or paper bags.

However, there is currently “no guideline in place for alternatives to plastics,” Sambyal said.

That could be a problem when the plastic ban takes effect.

A machine picking up waste in the pile of garbage at the Ghazipur land fill site where city’s daily waste has been dumped for last 35 years. The machine separates waste into three parts first stone and heavy concrete material second plastic, polythene and third is fertilizer and soils.

Pradeep Gaur | SOPA Images | LightRocket | Getty Images

Sambyal said clear rules are needed to promote alternative options, which are expected to become commonplace in future.

The new rules also lack guidelines on recycling.

Though around 60% of India’s plastic waste is recycled, experts worry that too much of it is due to “downcycling.” That refers to a process where high-quality plastics are recycled into new plastics of lower quality — such as plastic bottles being turned to polyester for clothing.

“Downcycling decreases the life of the plastic. In its normal course, plastic can be recycled seven to eight times before it goes to an incineration plant … but if you downcycle, after one or two lives itself, it will have to be disposed,” said Pandey from Teri.

In India’s state of Maharashtra, people are seen carrying bags of other materials, mostly cotton for their daily routine and shopping on June 24, 2018 in Pune, India.

Rahul Raut | Hindustan Times | Getty Images

Tackling waste segregation is also essential.

If general waste and biodegradable cutlery are disposed together, it defeats the purpose of using plastic alternatives, according to Sambyal.

“It is high time that source segregation of domestic waste is implemented vigorously,” said Foundation for Campaign Against Plastic Pollution’s Srivastava, referring to waste management laws that are in place, but not followed closely.

Way forward

Environmentalists generally agree that the ban is not sufficient on its own and needs to be supported by other initiatives and government regulations.

The amount of plastic that is collected and recycled needs to be improved. That comes from regulating manufacturers and asking them to clearly mark the type of plastic used in a product, so it can be recycled appropriately, said Pandey.

A women rag picker collecting plastic bottle and other plastic materials in a boat from the bank of Brahmaputra River in Guwahati, Assam, India on Monday, October 29, 2018.

David Talukdar | NurPhoto | Getty Images

In addition to improving recyclability, investment in research and development for alternatives should also be a priority.

Pandey explained that India is a big, price-sensitive market where plastic alternatives could be produced in bulk and sold at affordable prices.

Several Indian states introduced various restrictions on plastic bags and cutleries in the past, but most of them were not enforced strictly.

Still, the latest ban is a big step toward India’s fight against landfill, marine and air pollution — and is in line with its broader environmental agenda, according to the experts.

In March, India said it was on track to meet its Paris agreement climate change targets, and added that it has voluntarily committed to reducing greenhouse gas emission intensity of its GDP by 33% to 35% by 2030.

WATCH LIVEWATCH IN THE APP

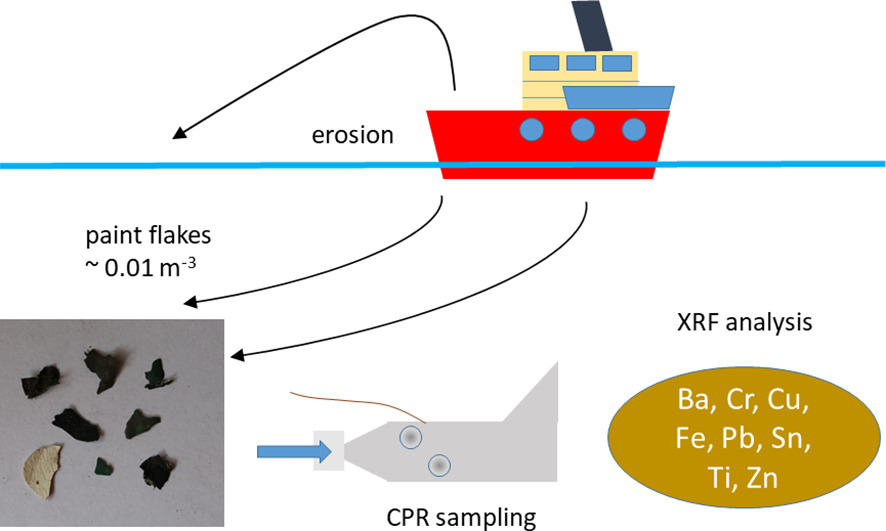

Paint flakes most abundant microplastic particles after fibers

A new report suggests that paint flakes could be one of the most abundant type of microplastic particles found in the ocean. As with other types of microplastics, the effect on marine life and the ocean are not yet fully understood.

The study, published in Science of the Total Environment and carried out by the University of Plymouth and the Marine Biological Association (MBA), conducted several surveys across the North Atlantic Ocean and estimated through more than 3,600 collected samples that each cubic metre of seawater contained an average of 0.01 paint flakes. This finding suggests that paint flakes are the second largest type of microplastic particles found in the ocean after microplastic fibres which has a concentration of around 0.16 particles per cubic metre.

The study further estimated that some of the paint flakes also had high quantities of lead, iron as well as copper due to them having antifouling or anti-corrosive properties. The researchers argued that this could further pose a threat to the ocean and the species living in it if they ingest the particles.

“Paint particles have often been an overlooked component of marine microplastics but this study shows that they are relatively abundant in the ocean. The presence of toxic metals like lead and copper pose additional risks to wildlife,” said Dr Andrew Turner, the study’s lead author and associate professor in environmental sciences at the University of Plymouth.

Therefore, paint flakes can be considered the most abundant type of microplastic in the ocean after fibres. And this development needs closer scientific attention as the full effect of the metallic additives on the ocean and its species is not yet fully understood.

For more from our Ocean Newsroom, click here.

Photography courtesy of Unsplash, graphical abstract found here.

Wilmington, NC, partners with groups, businesses to cut plastic waste

Tricia Monteleone, left, vice president of Plastic Ocean Project Inc., and Bonnie Monteleone, the group’s executive director, pose during an event in September at Waterline Brewing Co. in Wilmington. Contributed photo by Moe Saur

Wilmington put in place a sustainability program in 2012 that recently has been trying to combat plastic pollution – especially plastic bags — through education and outreach, with the help of a state grant and partnerships with nonprofit organizations.

The sustainability program aims to efficiently manage energy, water and waste, “while cultivating a culture of environmental stewardship throughout city operations to reduce our environmental footprint. We strive to implement fiscally and environmentally sound projects to preserve the quality of life of our community and resources,” according to the city.

Part of the outreach included having the city council approve in September a resolution to reduce plastic waste and support Ocean Friendly Establishments, a nonprofit initiative that encourages businesses and nonprofits to reduce single-use plastics.

David Ingram, Wilmington’s sustainability project manager, who has been in this role since 2015, said in an interview that the resolution ties in nicely with his department’s outreach work funded through a state grant from the 2020 Community Waste Reduction and Recycling Grant Program.

The city was awarded $16,917 with a $3,383 match requirement, totaling $20,300 toward the effort. The grant, which was put in place to help local governments in expanding, improving and implementing waste reduction and recycling programs, is administered by the North Carolina Division of Environmental Assistance and Customer Service through the Solid Waste Management Outreach Program, according to city officials.

City officials apply for this grant each year. This year, they pitched building the city’s recycling program with a focus on increasing public awareness of waste reduction and recycling and supporting the statewide Recycle Right NC campaign as well as promote the “Mayor’s Plastic Bag Challenge,” an effort to reduce single-use plastic bag usage.

“This year, the focus of that grant was really just a lot of outreach and education in regards to not only Recycling Right, but also promoting the use of reusable bags to help eliminate the use of single-use plastic bags,” Ingram said.

Ingram said the city had used the grant to take numerous steps to educate residents and help them understand what can be recycled, including Recycle Right NC materials. “We really tried to kind of simplify and make it more streamlined,” he said.

The city program also purchased reusable bags to hand out and provided some to the Plastic Ocean Project to distribute at their recent events, Ingram added.

“I would say to this particular grant, the education outreach efforts will be ongoing, and we have quite a few more reusable bags to distribute. We have a lot of messaging just in regard to Recycling Right,” he said. “Going forward, we hope to collaborate on some other events as well just to continue that messaging.”

Ocean Friendly Establishments is an initiative of the Plastic Ocean Project, which aims to educate the public and help address the global plastic pollution problem.

Plastic Ocean Project Executive Director Bonnie Monteleone told Coastal Review that it didn’t take long to convince the city council to approve a resolution of support for the effort, but COVID-19 delayed progress for more than a year.

“As the saying goes, it takes a village,” Monteleone said, adding Ingram played a major role in bringing the resolution to the city council. Numerous Wilmington Ocean Friendly Establishments committee members joined in the effort along with help from the North Carolina Aquarium at Fort Fisher.

Monteleone noted that the bag campaign to encourage using reusable bags is in line with the city council’s resolution and with Plastic Ocean Project efforts in general.

“We are in the process of designing a ‘Got your bag’ logo that will be displayed in parking lots and billboards,” Monteleone said. Plastic Ocean Projects is also connecting with grocery stores to provide educational materials and the reusable bags from the city. “We hope to initiate the campaign mid-November that will focus on a positive message.”

Monteleone explained that the Ocean Friendly Establishment program began with just addressing the use of straws, encouraging restaurants to only give them out upon request. “It has now grown into a five-star program. This a perfect example of how one small effort can turn into a movement. We hope the bag campaign will do the same.”

Ocean Friendly Establishments is the brainchild of Ginger Taylor, a volunteer for the Wrightsville Beach Sea Turtle program, who saw the need for a solution to plastic straw litter, Monteleone said. Taylor was troubled by the number of straws she picked up in Wrightsville Beach while walking the strand identifying turtle tracks and pitched her idea at a North Carolina Marine Debris Symposium, an annual symposium featuring presentations by environmental and educational groups on different efforts to tackle marine debris.

Through the work of the Plastic Ocean Project, the North Carolina Aquarium at Fort Fisher and other organizations including the North Carolina Aquarium’s Jeanette’s Pier and nonprofits such as Keep Brunswick County Beautiful, the North Carolina Coastal Federation and Crystal Coast Riverkeepers, Ocean Friendly Establishments now has more than 200 establishments, including businesses, restaurants, breweries and nonprofits. “It’s a great example of the power of one and our very caring communities,” she said.

What makes the Ocean Friendly Establishments program successful is the numerous volunteers that make up many committees along the coast. “They are truly the driving force behind the success of this program as well as the resolutions,” she said.

A self-regulating, community-based certification program, Ocean Friendly Establishments has its own website where volunteers can join committees and businesses can apply for certification.

“It all comes down to using less plastic. Nature did not design plastic and therefore does not know what to do with it, hence it persists in the environment indefinitely. Because it can persist for decades and in some cases centuries, it can wreak havoc on the natural world and sadly is. The solution to plastic pollution is to reduce. If we don’t use it, we can’t lose it,” she said.

Why is plastic a problem?

Ingram told the city council in September that while the city has a long history of being a steward of the coastal environment, “We do recognize that plastic film and single-use plastics represent a contamination in our local environment, as well as our waste stream.”

Ingram said that plastic bags, while they are recyclable, tend to be placed in either curbside recycling or in locations that are not the proper place to drop these items off. When that happens, the bags impede the recycling process at many of the materials recovery facilities. The bags clog the system and force the machinery to be shut down, leading to delays and increased costs.

“This plastic film and bags, as well as straws, represent an enormous impact to our local waterways, when they don’t make it into our recycling or waste stream,” Ingram said. “They break down into small fragments that not only float on the surface of our waters but actually can sink down to the bottom and be very difficult to ever remove from the environment.”

Monteleone said Americans use more than 1 billion plastic bags a year – about 365 bags per person — which in total equals about 12 million barrels of oil.

While these bags can be recycled, many are not and chemicals leech out from the plastic bags and are starting to affect animals. Organisms that convert carbon dioxide into oxygen are compromised because of plastics. “These are getting lost in the environment and wreaking havoc on our marine life. “

About 70% of the Earth’s surface is covered in water and anything that ends up in the environment has the potential of getting into storm drains and into rivers, which lead to the ocean.

Newsom signs laws banning 'forever chemicals' in children's products, food packaging

California Gov. Gavin NewsomGavin NewsomOvernight Energy & Environment: White House to restore parts of Trump-lifted environmental protections law Equilibrium/Sustainability — Presented by The American Petroleum Institute — NASA to unleash ‘planetary defense’ tech against asteroid Schwarzenegger: Jan. 6 shows what happens ‘when people are being lied to about the elections’ MORE (D) signed two laws on Tuesday banning the use of toxic “forever chemicals” in children’s products and disposable food packaging, as well as a package of bills to overhaul the state’s recycling operations, his office announced that evening.“California’s hallmark is solving problems through innovation, and we’re harnessing that spirit to reduce the waste filling our landfills and generating harmful pollutants driving the climate crisis,” Newsom said in a press statement.The pollutants driving the first two laws are perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), a group of toxic compounds linked to kidney, liver, immunological, developmental and reproductive issues. These so-called forever chemicals are most known for contaminating waterways via firefighting foam, but they are also key ingredients in an array of household products like nonstick pans, toys, makeup, fast-food containers and waterproof apparel.ADVERTISEMENTOne of the laws, introduced by Assemblywoman Laura Friedman (D), prohibits the use of PFAS in children’s products, such as car seats and cribs, beginning on July 1, 2023, according to the governor’s office.“As a mother, it’s hard for me to think of a greater priority than the safety and well-being of my child,” said Friedman in a news release from the Environmental Working Group (EWG). “PFAS have been linked to serious health problems, including hormone disruption, kidney and liver damage, thyroid disease and immune system disruption.“This new law ends the use of PFAS in products meant for our children,” she added.Bill Allayaud, EWG’s director of California government affairs, praised Newsom “for giving parents confidence that the products they buy for their children are free from toxic PFAS.”“It’s heartening that for this legislation, the chemical industry joined consumer advocates to create a reasonable solution, as public awareness increases of the health risks posed by PFAS exposure,” he said in a statement.ADVERTISEMENTBecause PFAS coating on infant car seats and bedding wear off with time, the toxins can get into dust that children might inhale, according to the EWG.The second PFAS-related law, proposed by Assemblyman Philip Ting (D), bans intentionally added PFAS from food packaging and requires cookware manufacturers to disclose the presence of PFAS and other chemicals on products and labels online — beginning on January 1, 2023.“PFAS chemicals have been a hidden threat to our health for far too long,” Ting said in a second EWG news release. “I applaud the governor for signing my bill, which allows us to target, as well as limit, some of the harmful toxins coming into contact with our food.”Despite the widely recognized risks of PFAS exposure, the Environmental Protection Agency has only established “health advisory levels” for the two most well-known compounds rather than regulate the more than 5,000 types of PFAS. States like California have therefore taken to enacting bits and pieces of legislation on their own. Although the House passed a bill in July that would require the EPA to set standards, companion legislation has yet to reach the Senate.“This law adds momentum to the fight against nonessential uses of PFAS,” David Andrews, a senior scientist at EWG, said in a statement. “California has joined the effort to protect Americans from the entire family of toxic forever chemicals.”ADVERTISEMENTAs far as recycling is concerned, Newsom signed a law banning the use of misleading recycling labels, as well as legislation designed to raise consumer awareness and industry accountability. The recycling bills serve to complement a $270 million portion of the state budget that will go toward modernizing recycling systems and promoting a circular economy, according to his office.Other measures in the recycling package include provisions to discourage the export of plastic that becomes waste, more flexibility for operations at beverage container recycling centers and labeling requirements to ensure that products designated as “compostable” are truly compostable.“With today’s action and bold investments to transform our recycling systems, the state continues to lead the way to a more sustainable and resilient future for the planet and all our communities,” Newsom said.

Greenland looks for ways to bust ghost fishing gear

Fishing gear continues to do what it is designed to do, even after it is discarded at sea. Here, fishing gear is wrapped around a whale fluke. (Naalakkersuisut)

So-called “ghost” fishing gear may be robbing the seas around Greenland of more than three tons of fish each year, at a total economic cost that amounts to 5 percent of the value of the country’s most important industry, an estimate by the research and environment ministry reckons.

Ghost gear — commercial fishing nets that are either lost or intentionally discarded at sea — poses a problem in Greenland and elsewhere not just because it continues to trap fish for as long as three years once it is in the water, but also because it can trap other animals. In addition, as the nets age, they break down into increasingly smaller plastic particles that are consumed by all manner of marine organisms, eventually making it into humans.

Half of the plastic that washes up on Greenland’s shores each year stems from the fishing industry. While this has alerted the public and lawmakers to the problem, its true extent is unknown, according to the ministry. That’s because most of the gear remains at sea — where fishermen say it ensnares other nets and fishing lines, which in many cases must be cut free, only adding to the problem.

[West Greenland’s plastic litter mostly comes from local sources, study finds]

There is no figure for the amount of fishing gear Greenland’s 1.2 billion kroner ($190 million) fishing industry loses each year, but there is evidence to suggest that it is significant. Using information from fishermen themselves as well as from regional authorities, the ministry calculates that, within three nautical miles of the coast, there may be a total 14,000 square kilometers (an area the size of two million soccer fields) where there is a moderate to high likelihood of finding ghost gear.

The biggest collections of gear may be in 19 hotspots where gear loss is most common, due to the type and intensity of fishing carried out in these areas, combined with conditions on the seabed that can result in nets getting caught or torn.

In recently published recommendations for preventing ghost gear, the ministry suggests starting clean-up efforts in three of the most heavily fished areas, covering a total of 420 square kilometers, where the concentration of ghost gear is likely to be greatest.

[Scientist calls for international cooperation to reduce marine plastics]

Such an effort would involve a ship collecting nets around the clock for a 12-week period each year, and take four to five years to complete, eventually costing 30 million kroner — about half of what the industry loses each year as a result of ghost gear.

The cost of successive cleanups would be lower, but factors such as weather, the distance to port facilities, sea ice and the presence of icebergs would still make it considerably more expensive to remove ghost gear from the waters off Greenland than those elsewhere. The proposed Greenland cleanup would probably cost twice as much as a similar, highly effective, Norwegian program.

While continued cleanups at land and sea will be necessary, the recommendations suggest that the amount of ghost gear can be reduced through financial measures — such as a surcharge or deposit — or by requiring that a net can be traced back to the vessel that lost it.

Such measures have worked in Iceland, where the revenue it generates goes to pay for cleaning collecting ghost gear at sea. The ministry warns, however, that most measures would entail a cost for fishermen, and that if the value of fishing gear increases, it is more likely to be stolen.

Indonesia marine plastic pollution problem highlighted in Gresik museum

Activists in Indonesia worried about plastic pollution wanted people to rethink their usage. So they built a museum made from more than 10,000 discarded bottles, bags, straws and single-use food packaging.The massive haul of items was fished out of local rivers and beaches that have become a dumping ground for such items, which pose a significant threat to marine life, ecosystems and communities around the world.The museum, which opened last month in the town of Gresik in East Java province, features thousands of plastic bottles that dangle overhead as visitors pass through the site, highlighting the sprawling impact of the marine crisis.While it is difficult to calculate precisely how much plastic has ended up in the world’s oceans, scientists have estimated that the yearly figure of waste being dumped could be as high as 12.7 million metric tons, according to data published in the journal Science.Plastics are virtually indestructible and while some items are biodegradable, it could take centuries for them to break down.Indonesia is among the world’s top contributors to plastic pollution, in a world where more than 8 million metric tons of plastic are dumped into oceans every year.It took activists from Indonesia’s Ecological Observation and Wetlands Conservation group three months to create the exhibit, which is known as “Terowongan 4444,” or “4444 tunnel.”Photos shared to the group’s official Facebook page in recent months highlight the extent of the plastic pollution problem. One image shows trash tangled in the low-hanging branches of trees lining riverbeds, while other images show activists bagging up countless sacks of debris.At the heart of the museum stands a statue of Dewi Sri, the goddess of prosperity, who is widely worshiped by the Javanese. The sculpture towers over visitors who are able to observe her skirt, which is made of discarded food and drink packaging — items that were bagged up by the group over the past few years.The group’s founder, Prigi Arisandi, told Reuters that the exhibition was built in a bid to spark change among people who may unwittingly be part of the problem.Wearing a T-shirt with a slogan that read, “I’m on a plastic diet,” Arisandi said he wanted visitors to become “educated” about the issue so they could help “reduce the use of single-use plastics.”“By looking at how much waste there is here, I feel sad,” one visitor told Reuters, while another told the agency he would be changing his consumer habits.“I will switch to a tote bag and when I buy a drink, I will use a tumbler,” Ahmad Zainuri said.Experts say that some initiatives to reduce individual plastic use, such as banning plastic straws, only have a minimal impact on plastic pollution — so wider efforts to ensure better waste collection and the use of recycled or biodegradable material are also essential.Along with the climate crisis, world leaders have also faced questions over the issue of plastic pollution, with advocacy groups calling on officials to do more to help struggling communities.Scientists have stressed that while it is paramount that officials take the issue of a warming climate seriously, the marine crisis should not be sidelined.“Climate change is undoubtedly one of the most critical global threats of our time,” Heather Koldewey of the Zoological Society of London told the BBC last month.“Plastic pollution is also having a global impact; from the top of Mount Everest to the deepest parts of our ocean,” she said, adding that both problems were intertwined and having a negative impact on ocean biodiversity.“It’s not a case of debating which issue is most important, it’s recognizing that the two crises are interconnected and require joint solutions,” Koldewey said.Read more:

The US falls behind most of the world in plastic pollution legislation

In recent years, countries across the globe have implemented laws to mitigate plastic production and pollution. In the past two years, both large developed nations like Australia and smaller developing countries like Sri Lanka and Belize have passed ambitious national laws to phase out a number of plastic products like bags, cutlery, and straws.

But the U.S., a leading producer and consumer of plastics, remains woefully behind, even as it stands as one of the world’s biggest polluters. According to the Environmental Protection Agency, the country produced 35.7 million tons of plastic waste in 2018, more than 90% of which was either landfilled or burned. The

U.S. ranks second in the world in total plastic waste generated per year, behind only China — though when measured per capita, the U.S. outpaces China. In 2019, the U.S. also opted not to join the United Nations’ updated Basel Convention, a legally binding agreement aimed at preventing and minimizing plastic waste generation that was signed by about 180 other countries.

More than 90 countries have established (or have imminent plans to establish) either bans or fees on single-use plastic bags or other products, according to data from the non-profit ocean conservation organization Oceana. The U.S. is not one of them. Though Americans have been aware of plastic pollution as an environmental concern as early as the mid-20th century, U.S. action against plastics has been piecemeal — the federal government has left it up to individual cities, counties, and states to decide whether and how to regulate plastics.

Related: Check out our Ocean Plastic Pollution guide

The plastic problem is growing increasingly urgent. More than

1 million plastic bags are used every minute, with an average “working life” of only 15 minutes. Experts believe the ocean will contain one ton of plastic for every three tons of fish by 2025 and, by 2050, more plastics than fish (by weight).

Not only does the ocean (and all life reliant on it) suffer from plastic pollution, but human health is also at risk. Microplastics have

well-documented impacts on human health, and have been found in 90% of bottled water and 83% of tap water. Our incessant plastic consumption is cultivated by “throwaway” culture, fueled by the plastic and oil and gas industries’ efforts to sustain high plastics consumption while distracting people with recycling campaigns.

This story is also available in Spanish

However, a new proposed federal bill—the

Break Free From Plastic Pollution Act—offers potential solutions, and could transform the U.S. from a hindrance to the global movement against plastics into a much-needed ally. Such federal action could help stop the fractured approach to tackling plastics in the U.S., and shift the burden from consumers to plastic manufacturers.

Advocates say even if the bill doesn’t pass in full, its component parts, especially those that are more bipartisan, could likely peel off and be recycled into other legislation. For example, a part of the bill addressing plastic pellets, or “nurdles,” has already broken off and become its own piece of potential legislation, the

Plastic Pellet Free Waters Act.

U.S. lags behind plastic pollution regulation

The European Union passed a comprehensive directive a couple of years ago. (Credit: campact/flickr)

Other countries not only produce less plastic than the U.S., but they’ve also more successfully legislated against plastic pollution. The European Union passed a comprehensive directive a couple of years ago, for example, that requires member countries to ban a slew of single-use plastic products, collect plastic bottles for recycling and reuse, and label disposable plastic products appropriately, at minimum. Many countries are going beyond those requirements.In Canada a federal ban on plastic bags, stir sticks, ringed beverage carriers, cutlery, straws, and food takeout containers made from hard-to-recycle plastics is set to take effect at the end of the year.It’s not just Western or “wealthier” nations who have successfully implemented measures against plastics. Dozens of countries across Africa, Asia, and Central and South America have legislation in place to quash the single-use plastic crisis.Christy Leavitt, the U.S. Plastic Campaign Director at Oceana, told EHN that the EU directive is just one example for the U.S. to emulate. Oceana has surveyed countries around the world, taking inventory of the global anti-plastic legislation and assessing where the U.S. sits comparatively, and found progressive policies in many pockets of the world.”Chile passed what is, if not the most comprehensive, one of the most comprehensive single-use plastic foodware policies in the world,” Leavitt said. Beyond banning single-use bags and straws, Chile prohibits all eating establishments from providing single-use cutlery or containers. Grocery and convenience stores must also display, sell, and take back refillable bottles, creating a cyclical system of bottle reuse.As early as 2002, the East African country Eritrea banned plastic bags in its capital city Asmara. The country implemented a nationwide ban on the import, production, sale, or distribution of plastic bags in 2005. Rwanda banned plastic bags in 2008 and then all single-use plastics in 2019, with heavy fines and even jail time for anyone found importing, producing, selling or using single-use plastic items.When countries across the globe with fewer resources than the U.S. successfully push out harmful plastic products, it gives the U.S. no excuse to be so behind, Leavitt added.

A fractured front on U.S. plastic pollution regulation

In the absence of national legislation in the U.S., local governments at the city, county, and state levels have regulated plastics. As a result, there is a diverse set of mandates and ordinances scattered across the country.

One paper in the Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning says that “as of August 2019, eight

U.S. states, 40 counties, and nearly 300 cities had adopted policies that, either through a ban, fee, or combination thereof, aim to reduce the consumption of single-use plastic bags.”

To Rachel Krause, a public administration researcher at the University of Kansas and author of the paper, it’s curious to see such a large issue relegated to local governments. “We tend to say that policy responses should be at scale or in proportion to policy problems,” she told EHN, “but local governments aren’t at scale with climate change, local governments aren’t at scale with global plastics. And yet, in a lot of places in the United States, that’s where we’re seeing the action happen.”

Local action against single-use plastic, by definition, has limited reach and is less efficient than sweeping national policy would be. Ordinances at a city or county level are also prone to being struck down by statewide preemption laws, when states ban local governments from taking action.

Eighteen states have some sort of preemption law in place. In Texas, for example, individual cities like Laredo tried to implement plastic bag bans, but the Texas Supreme Court knocked them down in 2018, saying they conflicted with state solid waste management laws.

That said, “the amount of just individual pieces of legislation that have been introduced at the state and local level, in the last five years has, increased by an order of magnitude, maybe more,” Alex Truelove, the Zero Waste Campaign Director with U.S. Public Interest Research Group (PIRG), told EHN. The legislative landscape felt so much more sparse just a few years ago, Truelove added — a great sign, since the more states engaging in anti-plastics discourse, the harder the issue is to ignore on a national level. Plus, “every time something passes, we learn something” about what does and does not work.

The problem is “it’s much easier to block something than to get something passed,” University of Southern Maine environmental policy researcher Travis Wagner told EHN. This is especially true at the federal level. He added that the federal government explored possible legislation against plastics as far back as the 1970s, as bottle bills were adopted around the country.

“Bottle bills,” also known as “container deposit laws,” typically work by mandating small deposits on drink containers like plastic bottles and metal cans that customers can get back if they recycle those bottles. Oregon passed the first bottle bill in the U.S. in 1971, and by 1986, 10 states had enacted some kind of bottle bill into law (there are still only 10 states doing this to date). In the 1970s, Wagner said, it seemed like there was enough momentum to pass a national bottle bill, “but politically, it was just really, extremely difficult.”

In the half century since the federal government first considered taking a national stance on plastics, the issue has only gotten worse.

Individuals get blamed as plastic production skyrockets

Historically, the conversation around plastic pollution in the U.S. has centered on individuals’ and communities’ abilities to recycle. (Credit: Brian Yurasits/Unsplash)

Historically, the conversation around plastic pollution in the U.S. has centered on individuals’ and communities’ abilities to recycle. But Leavitt said that recycling was an ideal pushed on the public by the plastics industry as “a way for [them] to put the blame of plastic pollution and the responsibility to fix it on consumers. And it worked. While we focused on recycling, industry exponentially increased the amount of plastic it produced.”The idea that it is the individual’s responsibility to recycle, to not litter, and to buy less was so pervasive “that it’s become embedded in our psyche,” added Wagner. “That’s the industry saying ‘It’s not us, it’s you.'”Meanwhile, records and reports from as early as 1973 suggest top industry executives knew that plastic recycling could never be successful on a large scale.”It’s all coming down to dollars and cents for the industry,” Shannon Smith, Manager of Communications and Development for the nonprofit FracTracker Alliance, told EHN. “The misperception is that there’s a demand for all of this plastic, and so the industry is just responding to the demand of consumers, where it’s really the opposite.” In reality, she added, there’s an oversupply of fracked gas in the U.S., and one of the best ways to profit from all that supply is to generate more demand for plastic. “So it’s totally industry driven.”Plastics are primarily made from the natural gas byproducts ethane and propane, which are turned into plastic polymers in high-heat facilities in a process known as “cracking.” The U.S. is the world’s leading producer of natural gas, with 30 cracker plants currently in operation and at least three more expected by mid-2022. To add insult to injury, Smith said, “the fracking industry has never been profitable,” and petrochemical companies and facilities are actually the frequent recipients of government subsidies. “We’re subsidizing them, we’re paying for their ability to make a profit while they’re sacrificing our health.”It’s time to put the responsibility of managing plastic waste back on the companies producing it, Truelove said. “If f your bathtub is overflowing, the first thing you do is turn off the tap,” he added.

Break Free From Plastic Pollution

Senator Jeff Merkley (D-OR), pictured here, and Representative Alan Lowenthal (D-CA), introduced the Break Free From Plastic Pollution Act. (Credit: merkley.senate.gov/)

A new piece of federal legislation seeks to turn off the proverbial tap. First introduced in 2020 and reintroduced in March 2021 by Senator Jeff Merkley (D-OR) and Representative Alan Lowenthal (D-CA), the Break Free From Plastic Pollution Act, if passed, would comprehensively address plastic production, consumption, and waste management in the country.”The idea behind the bill was to really kind of assemble all of the best ideas from not just around the country, but honestly from around the world,” said Truelove. The EU directive, for example, was a great precedent and a beacon for the direction the U.S. could follow, he added.Congressman Lowenthal wrote to EHN that “this bill incorporates best practices and important common-sense policies. While it may be ambitious – it is by no means radical.” The bill would ban single-use plastic bags and other non-recyclable products, include a bottle bill, and channel investments to recycling and composting infrastructure. “The legislation makes producers responsible for the end use of their own products,” added Congressman Lowenthal. Producers of plastic packaging would be required to design and finance waste and recycling programs.Truelove also mentioned that the bill, importantly, sets a minimum for states to abide by, allowing individual local governments to pursue or keep more aggressive policies —”we don’t want to punish the states that have those stronger laws.”The proposed bill also includes components of environmental justice, requiring the EPA and other agencies to more rigorously study the cumulative environmental and health impacts of incinerators and petrochemical plants, while also placing a moratorium on new or expanding facilities. Frontline and fenceline communities — so named because they are situated next to these industrial plants, right up to the fences — are the most harmed by the poor air and water quality inflicted by the plastics industry. They are also disproportionately communities of color.

The future of plastics regulation

The Break Free From Plastic Pollution Act has not been put into law yet. It is currently co-sponsored by 12 other senators, but the timeline for when it might be passed is still very unclear.Truelove is hesitant to make predictions, but he’s optimistic that, in the long run, some form of federal legislation will pass. Wagner is more skeptical: “I am optimistic, but not at the national level.” In his mind, individual states will continue to lead.Though the full Break Free From Plastic Pollution Act has no clear path forward t at the moment, pieces of the bill are already breaking off and being discussed more seriously. Lowenthal wrote that breaking off elements of the bill and integrating them with more narrowly focused legislation with bipartisan support, or attaching them to bills at the verge of being passed, is a practical move to get parts of the bill through Congress bit by bit. “A lot of this work tends to be incremental. It almost has to be, by nature, just the way our institutions are built,” said Truelove.But even if the bill is passed, it’s still no panacea. The plastics and petrochemical industries will likely continue pushing for what Truelove calls “false solutions,” like chemical recycling innovations (where plastics are broken down again into polymers, effectively turning them into diesel fuel — a different environmental nightmare) or flashier anti-littering campaigns.”What we’re doing is an affront to [industry’s] business model,” he added. “You’ve got Dow, DuPont, Chevron, Exxon, and so on…and they’re incredibly powerful organizations with a lot of political influence.” To substantially move towards less plastic production and more reusable products, the government will need to push past those distracting pseudo-solutions, even when they seem like they could be profitable.”It’s totally doable,” said Truelove. “I mean, I think if we can get to the moon, we can figure out how to make it easy for people that have reusable foodware or reusable packaging for shipping.”Banner photo credit: Naja Bertolt Jensen/Unsplash

Research reveals how much plastic debris is currently floating in the Mediterranean Sea

Credit: Unsplash/CC0 Public Domain

A team of researchers have developed a model to track the pathways and fate of plastic debris from land-based sources in the Mediterranean Sea. They show that plastic debris can be observed across the Mediterranean, from beaches and surface waters to seafloors, and estimate that around 3,760 metric tons of plastics are currently floating in the Mediterranean.

Environmental groups push for Pittsburgh plastic bag ban

Environmental advocacy nonprofit PennEnvironment released a letter Wednesday signed by 100 Pittsburgh businesses and organizations in support of a plastic bag ban, an ordinance expected to come before City Council later this fall.“We estimate this policy has the potential to prevent 108 million plastic bags from entering our waste stream in our environment each year,” said Ashleigh Deemer, deputy director of PennEnvironment. “These signers represent businesses, community organizations, and nonprofits, and every Pittsburgh City Council district.”The letter is part of Penn Environment’s broader campaign to pass a plastic bag ordinance in Pittsburgh, an effort the organization successfully undertook in Philadelphia, where a plastic bag ban took effect July 1.The Pittsburgh ordinance has been under discussion for several years. It was delayed by a 2019 Pennsylvania legislature ban on municipal plastic bag ordinances, provoking a lawsuit led by Philadelphia and other municipalities. Then in May, in anticipation of the end of the ban on plastic bag bans, Pittsburgh City Council passed a resolution to introduce a plastic bag ordinance.Though most of the letter’s 100 signatories are small businesses and organizations, some larger retailers are preparing for a potential ban. Whole Foods does not use plastic bags—and in 2019, Giant Eagle announced plans to phase out single-use plastic bags by 2025.In March, PennEnvironment released the results of a survey showing microplastics were found in every Pennsylvania waterway tested. Film microplastics, which are fragments from plastics bags, were found in all three of Pittsburgh’s rivers, including the Allegheny River, from which Pittsburgh draws its drinking water.“It’s estimated that people consume about a credit card’s worth of plastic each week,” Deemer said. “Once microplastics are in our environment and in our water, there’s really no effective way to remove them. So the best thing that we can do is stop plastic pollution at the source and plastic bags are one source of microplastics.”Plastic bag bans in several hundred other cities have had mixed results. In particular, early-adopting cities like Austin and Chicago found that banning only thin plastic bags pushed large retailers in particular to offer customers thicker-gauge plastic bags touted as reusable, resulting in higher plastic use than before the bans. Other retailers offered paper bags, which come with environmental impacts of their own.Deemer said PennEnvironment has been working with City Councilor Erika Strassburger’s office to make policy recommendations as they draft the ordinance, to help avoid some of the unintended consequences experienced in other cities.“In terms of making sure that this doesn’t create a bigger plastic problem and encourage thicker plastic bags, it’s all in the definition that’s in the bill,” Deemer said. “We want to make sure that the definition of plastic bag in this bill is just ‘blown-film extrusion.’ It’s the way that the plastic bags are made, no matter the thickness of the plastic, so that we’re not trading thin plastic for thick plastic.”Deemer said they are also advocating for the ordinance to define acceptable paper bags as ones made of post-consumer recycled paper. Both the “blown-film extrusion” language and the precision of post-consumer recycled paper bags are part of the model ordinance PennEnvironment developed for Pennsylvania municipalities considering plastic bag ordinances.It is not clear what provisions will be included in the Pittsburgh ordinance. In July, in an interview on WESA’s the Confluence, Strassburger said the Pittsburgh ordinance may include both a ban on plastic bags and a fee on paper bags. This strategy is among the best practices recommended by the Surfrider Foundation, a nonprofit ocean protection organization.In a release, Strassburger said she plans to introduce the plastic bag ordinance this fall.