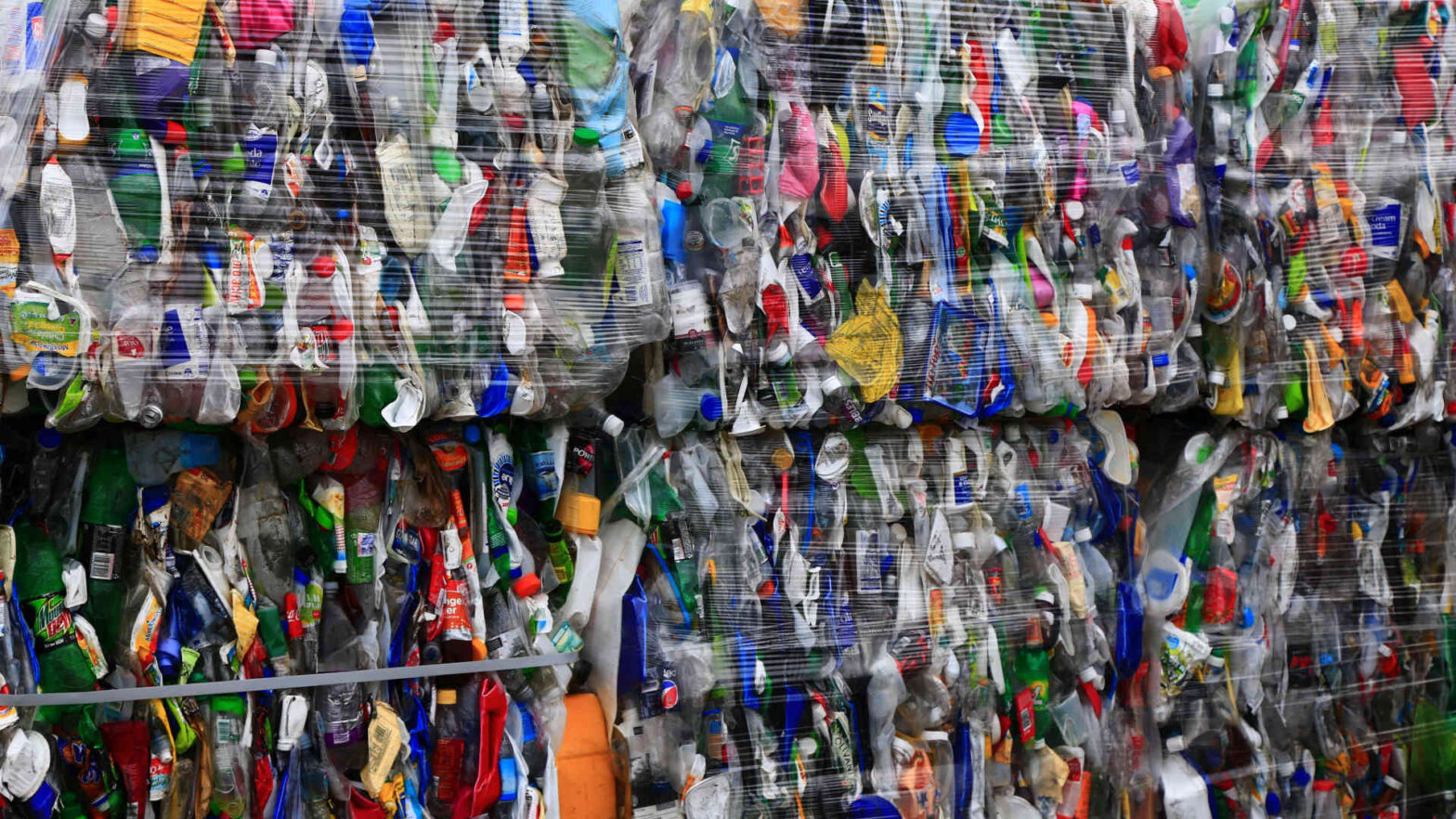

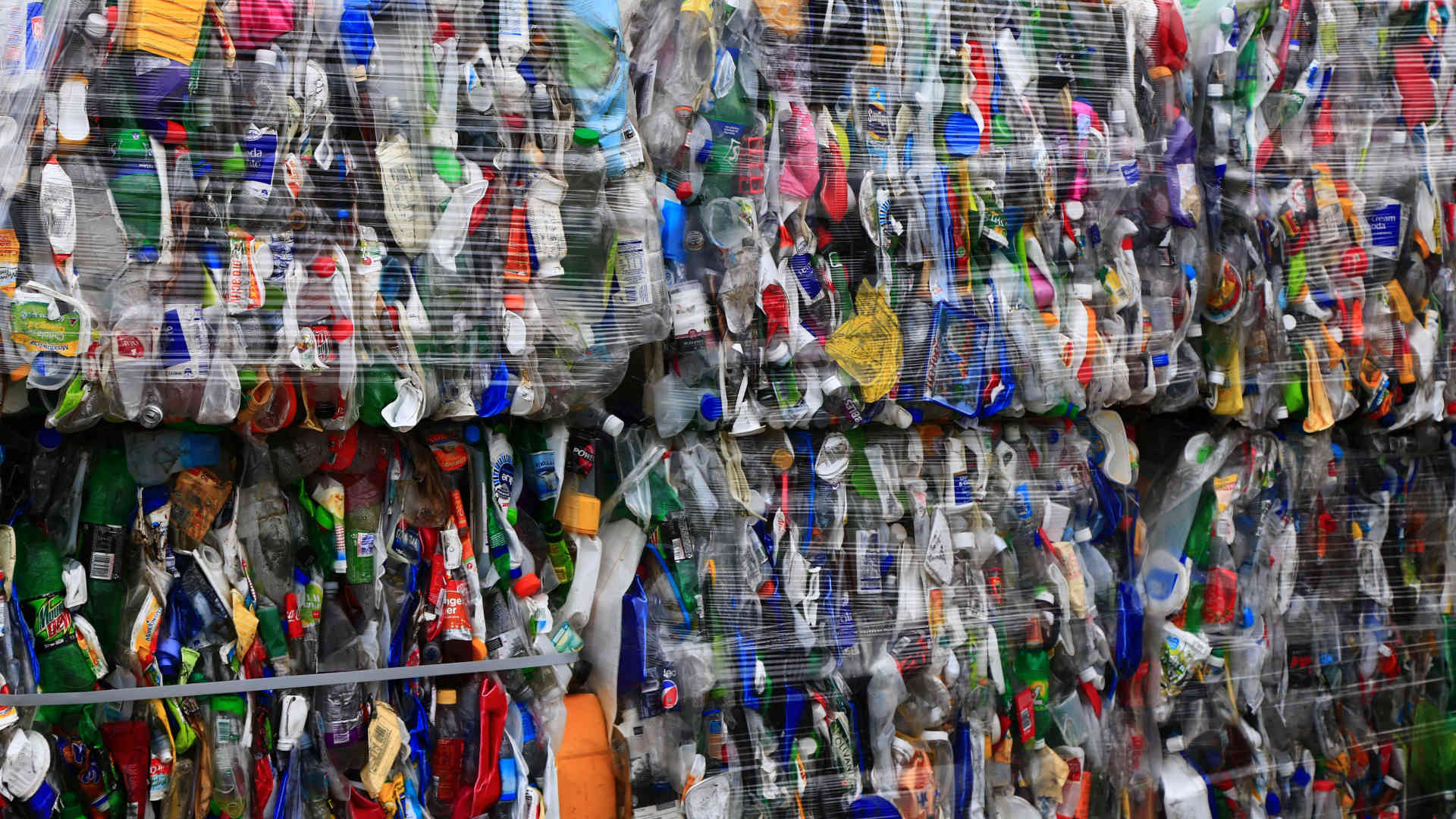

Every year, people around the world use more than 500 billion plastic bags, the majority of which are used for grocery shopping. While these plastic bags are convenient for shoppers, they only have a 15-minute lifespan, which means they are usually thrown away after only 15 minutes of use. As a result, plastic bags are one of the most significant contributors to plastic waste globally.

One of the most effective ways to combat this plastic waste problem is to use reusable shopping bags. In this article, we’ll review the best reusable and sustainable grocery bags made of natural fibers such as cotton, hemp, and jute.

Background Information: How to Find the Best Reusable Grocery Bags for You

How We Picked the Best Reusable Bags Made of Natural Fibers

Using any reusable cloth bag is usually more eco-friendly than using single-use plastic bags for everyday shopping. But not all reusable bags are made equal, as some are more sustainably-made than others. Here are the factors we considered in our research to make sure we picked the very best sustainable reusable bags made of natural fibers.

Capacity

One of the most important purposes of shopping bags is to ensure that you are able to carry all your goods in one place, especially when you are buying a lot of items. We chose reusable bags that have large capacities, ensuring they’re convenient for the average grocery trip.

Materials

We chose products made from lower-impact sustainable plant-based fibers, including:

- Cotton

- Hemp

- Jute

Natural fiber bags are often considered more eco friendly than plastic as they are entirely biodegradable. However, the manufacturing process of natural materials still requires resources that are critical to the environment, such as water to grow the plants and energy to manufacture the bags, which emits carbon as well.

In order for natural fiber bags to actually be more sustainable than single-use plastic, it’s important that you use them as many times as possible. For example, you need to use a cotton bag 173 times before it’s more eco-friendly than a disposable plastic bag.

Read more about these natural materials and their benefits and drawbacks: What Are Reusable Bags Made Of?

Quality & Durability

A grocery bag isn’t very useful if it can’t carry heavy loads of food, so we’ve made sure to pick the most durable, well-made reusable bags. For example, we made certain that none of these bags will rip while carrying your goods and won’t degrade under harsh weather conditions, such as rain, humidity, or heat. Durability also makes the bags more sustainable, as you’ll be able to get more use out of the bag before you need to replace it.

Manufacturer’s Ethical & Sustainable Practices

Finally, we’ve reviewed each manufacturer’s adherence to other sustainable and ethical standards. For example, we reviewed whether the manufacturer ensures fair wages and safe working conditions and if they engage in other sustainable practices such as relying on renewable energy or using sustainable packaging.

Reusable Bags Made of Natural Fibers: Our Top Picks

The US consumes over 100 billion plastic bags a year, but only a very small percentage of those are actually recycled. The rest end up in the oceans and landfills where they continue to take up space and release harmful pollutants into the atmosphere. While some supermarkets and grocery stores are switching to paper bags, if you’re grocery shopping frequently, it is best to simply bring a reusable bag for your daily or weekly shopping. Here are our picks for the best sustainable reusable bags made of natural fibers.

- 1. Earthwise Reusable Bags – Heavy Duty Cotton Tote with Outer Pocket

- 2. The Common Good Company – 100% Recycled Cotton Market Tote

- 3. NEOCOCO – Recycled Cotton Canvas Tote

Our Top Recommendation Rankings

- Most Spacious Reusable Bag

- Best for Heavy Duty Reusable Bag

- Most Affordable Quality Reusable Bag

- Most Stylish Reusable Bag

Best Cotton Reusable Bags

1. Earthwise Reusable Bags – Heavy Duty Cotton Tote with Outer Pocket

- Manufacturing Company: Earthwise Reusable Bags

- Amazon Star Rating: 4.5

- Current Price: $10.99

- Materials: Cotton canvas

- Capacity: 22″ W x 16.5″ H x 5.5″ D

- Get This Bag: Amazon

Earthwise’s heavy-duty cotton tote bags are composed of 100% cotton canvas. Cotton-based canvas is more sustainable than plastic materials commonly used in bag manufacturing because its production requires fewer chemicals and the fabric is biodegradable.

This bag is strong and sturdy, with plenty of space, making it ideal for shopping with a large or heavy load. The strap is also made with heavy duty stitching and measures 28 inches long for convenient shoulder carrying. The bag is built with a strong zipper closure, which is a big plus for keeping your items from falling out of your bag. Conveniently, the bag also features an outside pocket for other items such as your wallet, receipts, money, a phone, and more.

This bag is available in navy blue and red.

If cotton isn’t for you, Earthwise is also collaborating with OceanCycle to create reusable bags made of 90% recycled plastic gathered from the ocean. This is a great example of sustainability efforts that not only help clean up the environment, but also repurpose waste into something useful.

Earthwise’s environmental initiatives go beyond simply providing sustainable reusable bags. The company works with Bureau Veritas to monitor its facilities across the world to ensure they comply with ethical and sustainable manufacturing practices. Earthwise also encourages its retailers to inspect its facilities in order to encourage transparency in their sustainable and ethical production.

Downsides: We’ve found that the Earthwise Cotton Tote shrinks overtime after being washed and dried. However, washing it in cold water and hanging it to dry can help to avoid this kind of problem.

You can also find this bag on the Earthwise website.

2. The Common Good Company – 100% Recycled Cotton Market Tote

- Manufacturing Company: The Common Good Company

- Amazon Star Rating: N/A

- Current Price: $27.43

- Materials: Cotton canvas

- Capacity: 19.68″ W X 15.75″ H x 3 .9″ D

- Get This Bag: The Common Good Company

The Common Good Company cotton tote bags are constructed of 100% recycled cotton canvas. Recycled cotton canvas means these bags are far more sustainable than cotton reusable bags made from virgin materials because they consume 99% less water and emit 50% less carbon.

This reusable bag is strong and spacious, and it can carry everything from heavy produce to gallons of milk. It has an interior pocket sealed with a snap button where you can store your other smaller items, preventing them from getting lost inside the bag and keeping things a little bit more organized.

The Common Good Company states that if their product is not ethically made then it’s not sustainable. The company has several certifications that demonstrate their commitment to ethical and sustainable practices. These include:

- B Corp certification

- Social Accountability International – SA 8000 certification

- Sedex SMETA certification

The Common Good Company also makes many other products from recycled cotton. Through their focus on sustainable materials, they’re able to conserve water and carbon with every product produced compared to conventional products. For example, for every cotton shirt they make from recycled cotton, they conserve 2,700 liters of fresh water.

This reusable bag is available in natural (white), olive, and charcoal.

Downsides: We’ve noticed that the strap on this bag is a bit shorter, measuring only 11 inches, making it more difficult to carry on your shoulder.

3. NEOCOCO – Recycled Cotton Canvas Tote

- Manufacturing Company: NEOCOCO

- Amazon Star Rating: None

- Current Price: $39

- Materials: Cotton canvas, Faux leather

- Capacity: H 14″ x W 11″ x D 6.5″

- Get This Bag: NEOCOCO

This NEOCOCO cotton tote bag is made of 100% recycled cotton canvas with faux leather handles. This elegant bag is a perfect go-to bag for everything from quick grocery trips to mall shopping to social gatherings, or even a stroll around the park. This multi-use functionality helps you use the bag more frequently, and thus helps the bag become more sustainable than a plastic bag more quickly!

While the quality of this reusable bag is durable and sturdy, it’s probably better for picking up a few grocery items than for heavy-duty carries. While the short straps make it difficult to carry heavy loads, you can still count on the bag to carry the essentials. The NEOCOCO tote also has a snap-button closure and an interior pocket to keep your smaller important items organized.

NEOCOCO has a “people before profit” mindset; for example, they are dedicated to employing women refugees and helping them achieve financial stability by ensuring they are well compensated. Every purchase of NEOCOCO recycled cotton tote bags supports refugee families with resettlement through providing housing, cultural adjustment, jobs, food supplies, education, and more. Aside from using recycled materials, NEOCOCO also promotes sustainability by committing to slow fashion and minimizing its carbon footprint by sourcing its materials locally.

Downsides: This bag is a little more expensive than other reusable tote bags. There are also no other colors available aside from natural. While this natural coloring makes the bag a bit more “simple” in design, it also helps avoid the environmental impacts of synthetic dyes.

Best Hemp Reusable Grocery Bags

4. Hemp Go Green – 100% Hemp Canvas Heavy-Duty Zippered Tote Bag

Hemp Go Green heavy-duty tote bags are made of 100% hemp canvas, which is one of the most sustainable natural fiber materials because it requires less water consumption than cotton, increases soil nutrients, and is extremely durable. We noticed that the canvas itself is thicker than many other tote bags, making it ideal for carrying heavy items again and again. The bag can be sealed with a heavy-duty metal zipper, and also includes two zipper-sealed small interior pockets for your smaller items, two metal rings on the exterior, and one metal ring in the interior, which can be used to clip items to your bag.

Hemp Go Green packaging is made of 100% recyclable cardboard boxes, helping their business avoid plastic waste entirely.

Downsides: We’ve noticed that although this reusable bag is washable, it becomes a bit floppy after washing it several times. This bag is also quite expensive compared to other tote bags and it doesn’t have other colors available aside from hemp green.

You can also find this bag on the Hemp Go Green website.

5. Hempnath – Saathi Tote Bag

- Manufacturing Company: Hempnath

- Amazon Star Rating: None

- Current Price: $25.65

- Materials: Hemp and Cotton

- Capacity: 13.38″ W x 14.17″ H x 1.96″ D

- Get This Bag: Hempnath

Hempnath Saathi tote bags are constructed of two sustainable materials: the exterior fabric is 100% hemp and the interior fabric is cotton. The bag’s design is simple and earthy, but the quality is excellent. The fabric is sturdy enough to carry heavy items, while the colorful design makes it perfect for other trips around town. The strap handle is only 11 inches long, a little shorter than other tote bags, but just right for a smaller and horizontally designed bag like this one.

Hempnath’s commitment to sustainability and ethical business practices extends beyond eco-friendly reusable bags. The company promotes reforestation efforts and supports marginalized communities in Nepal by collaborating with a number of organizations, including:

This reusable bag is available in natural, mustard, light blue, brown, forest green, and orange colors

Downsides: Compared to other reusable bags in our top picks, this bag doesn’t have any security features like zippers or snap closures, so your things might slip out if you’re not careful. There are also no pockets inside or outside the bag.

6. Urbane Luggage Hemp Tote

- Manufacturing Company: Urbane Luggage

- Amazon Star Rating: 5

- Current Price: $39

- Materials: Hemp

- Capacity: 17″ W x 15″ H x 4″ D

- Get This Bag: Amazon

Urbane Luggage tote bags are made of 100% hemp herringbone fabric, making them incredibly sustainable and long-lasting. This reusable bag’s design is simple, providing the perfect no-fuss tote bag design that’s also strong and spacious enough to carry large and heavy items. We’ve also noticed that the bag is lighter and packs up smaller than the other hemp bags on our list, which makes it perfect for stowing in your car for quick trips to the store. The strap handles extend 12 inches and are padded for extra comfort on your shoulder. This reusable hemp bag also has a 6-inch zippered interior pocket to keep your little items safe. Finally, the bag has a swivel ring hook feature for your keys.

Urbane Luggage is strongly anti-fast fashion. All bags are made on-demand after they’re ordered, helping to reduce excessive production waste. Their materials are also sourced locally, which cuts carbon emission from overseas shipping.

This reusable bag is available in purple ash (a lavender-like color) and warm sand (a cream-like color).

Downsides: Aside from its zipped interior pocket, this reusable bag doesn’t have any security features like zippers or snaps.

You can also find this bag on Urbane Luggage website.

Best Jute Reusable Bags

7. BeeGreen – Burlap Tote Bag

- Manufacturing Company: BeeGreen

- Amazon Star Rating: 4.7

- Current Price: $14.99

- Materials: Jute

- Capacity: 17″ W x 12.6″ H x 7.09″ D

- Get This Bag: Amazon

BeeGreen burlap tote bags are made of 100% natural jute fabric, which is extremely sustainable as jute relies only on rainwater to grow, grows quickly, and captures carbon faster than other trees. Jute fabric is also durable, water resistant, and most importantly, compostable. In some areas, you can even recycle jute!

Jute fabric provides this bag with extreme strength. This is also one of the biggest bags on our list, making it ideal not only for shopping for large and heavy goods, but also for other outdoor activities such as going to the beach, picnicking, or using it as a gym or yoga bag. The bag has a 7-inch zipped interior pocket that is perfect for holding your phone, wallet, and other small essential items. Another characteristic that distinguishes this bag from our other top recommendations is that it features an inside lamination that makes it water resistant, making it a great alternative to plastic bags.

This reusable bag is only available in one natural brown base color, but it comes in a variety of creative prints.

Downsides: Aside from its zipped interior pocket, this reusable bag doesn’t have a top closure.

You can also find this bag on BeeGreen website.

8. Kaf Home – Jute Bags

- Manufacturing Company: Kaf Home

- Amazon Star Rating: 4.7

- Current Price: $14

- Materials: Jute

- Capacity: 17″ W x 12.5″ H x 7″ D

- Get This Bag: Amazon

Kaf Home tote bags are also made of 100% natural jute fabric. This bag is strong enough to carry large items and is also spacious, making it perfect for large grocery trips. Because the handle on this bag is shorter and narrower, we recommend carrying it by hand rather than on your shoulder. This reusable jute bag includes an interior zipped pocket to keep track of your things, and interior lamination, which makes it water-resistant and able to handle spills.

Kaf Home is committed to ensuring socially and environmentally responsible practices throughout their production process. For example, Kaf Home is an amfori Business Compliance Initiative member, which helps them ensure social standards are met in their supply chain.

This reusable tote bag is only available in one natural brown color, but it comes in a variety of creative prints.

Downsides: We noticed that the fabric (especially on the handles) can fray over time.

You can also find this bag on the Kaf Home website.

Our Top Recommendation Rankings

Most Spacious Reusable Bag: Earthwise Reusable Bags – Heavy Duty Cotton Tote with Outer Pocket

We chose Earthwise’s heavy-duty cotton tote with an outer pocket as the most spacious natural fabric reusable bag. At 16.5 inches tall and 22 inches wide, this bag can carry groceries for even the largest groups of people!

Most Heavy-Duty Reusable Bag: Hemp Go Green – 100% Hemp Canvas Heavy-Duty Zippered Tote Bag

We chose Hemp Go Green zippered tote bag as the best heavy-duty bag due to its strong durability features and its capacity to carry heavy items. You’ll be using this bag over and over again for years.

Most Affordable Reusable Bag: BeeGreen – Burlap Tote Bag

We chose the BeeGreen burlap tote bag as the most affordable reusable bag on our list, as it’s cheaper than many other sustainable reusable totes. The bag is still extremely high quality and is great for a variety of uses.

Most Stylish Reusable Bag: NEOCOCO – Recycled Cotton Canvas Tote

NEOCOCO’s recycled cotton canvas tote bag is the clear winner for the most stylish natural fabric reusable bag due to its elegant and unique design, including faux leather handles.