EDITORIAL

08 March 2022

Landmark treaty on plastic pollution must put scientific evidence front and centre

United Nations resolution on greening plastics is a positive step. As negotiations begin, they must be evidence-based.

Download PDF

Leila Benali (left), Morocco’s minister for energy and sustainablity, and UN Environment Programme chief Inger Andersen celebrate the decision to begin talks on a plastics treaty.Credit: Tony Karumba/AFP/Getty

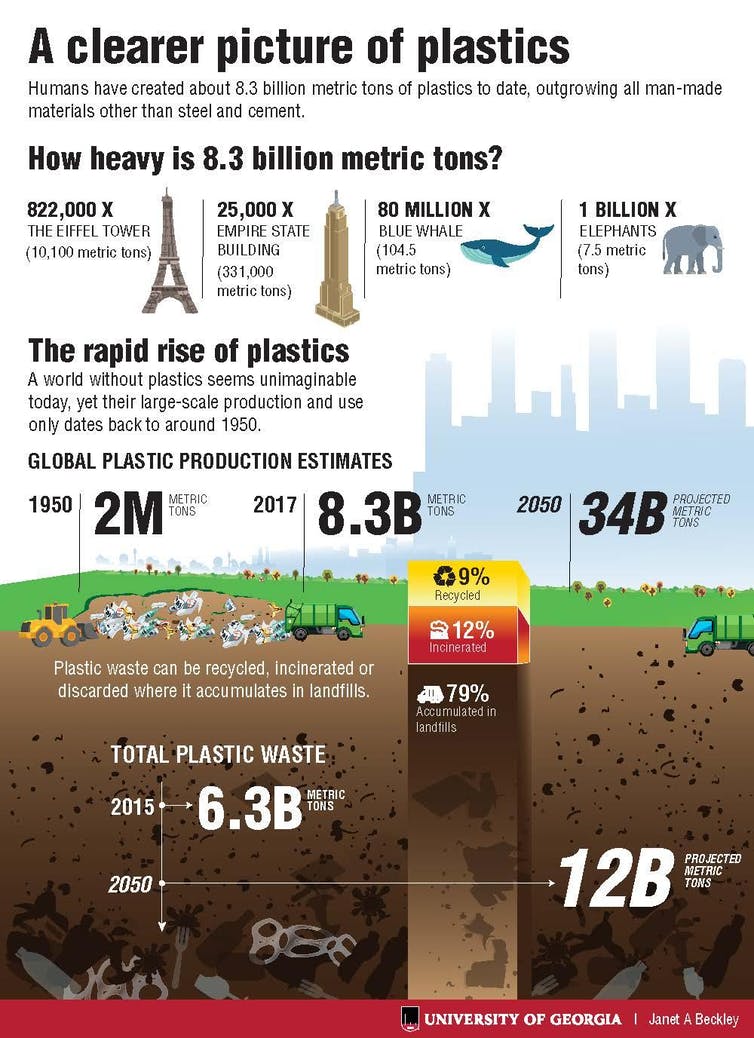

On 2 March, world leaders and environment ministers agreed to start negotiations on the world’s first legally binding international treaty to eliminate one of humanity’s most devastating sources of pollution: plastics. This hugely positive step has the power to attack the problem as never before. But to achieve this goal, science needs to be front and centre in the negotiations.Plastic pollution is a massive problem. Some 400 million tonnes of the material is produced each year, a figure that could double by 2040. Of all the plastic that has ever been produced, only about 9% has been recycled and 12% incinerated. Almost all other waste plastic has ended up in the ocean or in huge landfill sites. More than 90% of plastics are made from fossil fuels. If left unchecked, plastics production and disposal will be responsible for 15% of permitted carbon emissions by 2050 if the world is to limit global warming to 1.5 °C above pre-industrial temperatures.Talks on the treaty are expected to take between two and three years and will be organized by the United Nations Environment Programme, based in Nairobi. A significant feature of the treaty is that it will be legally binding, like the 2015 Paris climate agreement and the Montreal Protocol, a 1987 treaty that led to the production and use of ozone-depleting substances being phased out.

How to globalize the circular economy

A team of negotiators from different regions is being established. By the end of May, they will start work on the treaty’s text. According to last week’s UN decision, these negotiators will consider “the possibility of a mechanism to provide policy relevant scientific and socio-economic information and assessment related to plastic pollution”. But they need to do more than just consider a mechanism. The UN must urgently set up a scientists’ group that can give the negotiators expert advice and respond to their questions. These science advisers would need to reflect the necessary expertise in the natural and social sciences, as well as in engineering, and represent different regions of the world.Nations want the plastics treaty to be more ambitious than most existing environmental agreements. Unlike the Montreal Protocol, which replaced around 100 ozone-depleting substances with ozone-friendly alternatives, countries have agreed that a plastics treaty must lock sustainability into the ‘full life-cycle’ of polluting materials. This means plastics manufacturing must become a zero-carbon process, as must plastics recycling and waste disposal. These are not straightforward ambitions, which is why research — and access to research — is so important as negotiations get under way.Most plastics are designed in a ‘linear’ one-way process: small, carbon-based molecules are knitted together with chemical bonds to make long and cross-linked polymer molecules. These bonds are hard to break, which makes plastics extremely long-lasting. They do not degrade easily and are difficult to recycle.Marine litter often grabs the headlines, but plastic pollution is everywhere. Landfill sites containing mountains of plastic blight our planet, and minuscule particles of plastic are found in even the most pristine environments. Such is the scale and persistence of plastics that they are now entering the fossil record. And a new human-made ecosystem — the plastisphere — has emerged that hosts microorganisms and algae1.

Chemistry can make plastics sustainable – but isn’t the whole solution

As negotiators get to work, they will need scientists to help them address several key questions. Which types of plastic can be recycled2,3? Which plastics can be designed to biodegrade, and under what conditions? And which plastics offer the best chances for reuse4? Moreover, social-sciences research will be essential to understanding the implications of — and inter-relationships between — the solutions that countries and industries will have to choose from. For example, new technologies and processes will have impacts on jobs. These impacts need to be studied so that risks to people’s livelihoods can be mitigated.Mapping out the implications of various approaches to greening the plastics industry will also require cooperation between governments, industry and campaign organizations — building on the cooperation that has brought the world to the start of negotiations.Plastics have made the modern world. They are a staple of daily life, from construction to clothing, technology to transport. But plastics use is also increasing at a rapid rate, and this is no longer tenable — around half of all plastics ever produced have been made since 2004.It is clear from the UN’s ongoing efforts to tackle climate change that it is not enough for a treaty to be legally binding. Signatories must also be held accountable, with regular reporting and checks on progress. Equally important is the need for science advice to be embedded in the talks from the earliest possible stage.Last week’s decision is the best start the planet could have had to tackling our plastics addiction. But as the hard work begins, decision-makers must be able to quickly and easily access the very best available evidence that research can provide.

Nature 603, 202 (2022)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-022-00648-9

ReferencesAmaral-Zettler, L. A., Zettler, E. R. & Mincer, T. J. Nature Rev. Microbiol. 18, 139–151 (2020).PubMed

Article

Google Scholar

Hopewell, J., Dvorak, R. & Edward, K. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 364, 2115–2126 (2009).PubMed

Article

Google Scholar

Coates, G. W. & Getzler, Y. D. Y. L. Nature Rev. Mater. 5, 501–516 (2020).Article

Google Scholar

Grigore, M. E. Recycling 2, 24 (2017).Article

Google Scholar

Download references

Related Articles

Ecology of the plastisphere

Chemistry can make plastics sustainable – but isn’t the whole solution

Circular chemistry to enable a circular economy

How to globalize the circular economy

Subjects

Green chemistry

Environmental sciences

Policy

Latest on:

Green chemistry

Rare metal helps to turn sunlight into fuel, day and night

Research Highlight 01 FEB 22

Solar power’s need for a carbon-intensive metal is set to soar

Research Highlight 27 JAN 22

Wind power versus wildlife: root mitigation in evidence

Correspondence 11 JAN 22

Environmental sciences

Madagascar’s biggest mine achieves striking conservation success

Research Highlight 07 MAR 22

An engineer advances fire-management laws in Colombia

Career Q&A 23 FEB 22

Unprecedented oil spill catches researchers in Peru off guard

News 18 FEB 22

Policy

Paul Farmer (1959–2022)

Obituary 10 MAR 22

Chile’s science transformation gains steam with new president

News 10 MAR 22

Taiwan’s pandemic vice-president — from lab bench to public office and back

World View 08 MAR 22

Jobs

Post-Doctoral Position (CRBS & IGBMC)

National Institute for Health and Medical Research (INSERM)

Strasbourg, France

PhD Fellowship in Carbon Capture and Gas Separation Technology

University of Stavanger (UiS)

Stavanger, Norway

NCMM Group Leader Position

University of Oslo

Oslo, Norway

Postdoctoral Scientist – PNAC – Dr Roger Williams – LMB 1798

MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology

Cambridge, United Kingdom