California aims to sharply limit the spiraling scourge of microplastics in the ocean, while urging more study of this threat to fish, marine mammals and potentially to humans, under a plan a state panel approved Wednesday.The Ocean Protection Council voted to make California the first state to adopt a comprehensive plan to rein in the pollution, recommending everything from banning plastic-laden cigarette filters and polystyrene drinking cups to the construction of more green zones to filter plastics from stormwater before it spills into the sea.The proposals in the report are only advisory, with approval from other agencies and the Legislature required to put many of the reforms into place. But the signaling of resolve from council members – including Controller Betty Yee and the heads of the Natural Resources and Environmental Protection agencies – puts California in the vanguard of a worldwide push on the issue.“What this action says is that we have to deal immediately with what has become a global environmental catastrophe,” said Mark Gold, executive director of the Ocean Protection Council. “We are moving ahead, while we continue to learn more about the science.”California Natural Resources Secretary Wade Crowfoot added: “By reducing pollution at its source, we safeguard the health of our rivers, wetlands and oceans, and protect all of the people and nature that depends on these waters.”Industry opposition has helped kill legislation that would force single-use packaging to be recyclable or compostable. But voters will have a chance in November to impose those requirements with the California Recycling and Plastic Pollution Reduction Voter Act. The ballot measure would force single-use plastics to be reusable, recyclable or compostable, with the goal of cutting plastic waste by one-fourth by 2030. The measure would charge up to one cent per item to provide incentive to reduce waste, with the funds going to recycling and cleanup measures.Scientists have estimated that 11 million metric tons of plastic spills into the ocean each year, an amount that could triple by 2040 without a course correction, the state’s report says.Microplastics are commonly defined as particles smaller than 5 millimeters (about 3/16 of an inch) in diameter. Some come from the breakdown of plastic bags, bottles and wraps, others are derived from clothing fibers, fishing gear and containers.A 2019 study of San Francisco Bay surprised some scientists when it concluded that the single largest source of microplastics was the tiny particles from vehicle tires that washed from streets into the bay.The often invisible pollution has been found not only in the most remote oceans, but in seemingly pristine mountain streams, in farmland worldwide and “within human placentas, stool samples and lung tissue,” the state’s report noted. Climate & Environment The biggest likely source of microplastics in California coastal waters? Our car tires Driving is not just an air pollution and climate change problem. Turns out, rubber particles from car tires might be the largest contributor of microplastics in California coastal waters, according to the most comprehensive study to date. A wide variety of chemicals in the microplastics have been shown to harm fish and other sea creatures — inflaming tissue, stunting growth and harming reproduction.The state’s plan outlined 22 actions to stem the problem, some designed to eliminate plastic waste at the source, others to cut off the waste before it gets into the air, storm drains and sewers and still others meant to enlighten the public about the problem.Some of the proposals attack highly visible segments of the waste stream.For years, environmental groups have routinely found microplastic-laden cigarette butts to be the most common form of trash in beach cleanups. The ocean protection agency suggested that California move this year to prohibit the sale and distribution of cigarette filters, electronic cigarettes, plastic cigar tips, and unrecyclable tobacco product packaging.Similarly, the group recommended a ban on foodware and packaging made of polystyrene, which includes Styrofoam. It sets 2023 as a target date for that restriction.The officials also recommended that state agencies use their own purchasing power to acquire reusable foodware whenever possible and to cut reliance on single-use utensils.Other changes, already adopted, need to be put into place, like a 2021 law that requires restaurants to provide single-use utensils and condiments only when customers ask for them.The state would also like to see manufacturers produce washing machines that filter out microfibers before they end up in storm drains. They would like vehicle tire makers to find alternatives that put less micro-waste on roadways. It’s unclear whether those changes will be mandated, or merely encouraged.For plastics that are not reduced at the source, the ocean group recommended a number of measures to restrict the flow of microplastics into storm drains, streams and into the ocean. Those solutions sometimes come under the heading of “low-impact development” and include creation of trenches, greenways and “rain gardens” that filter and hold waste before it flows out to sea. One woman’s crusade: a clean patch of beach One woman’s crusade: a clean patch of beach It also recommended placing more trash cans along beaches and other “hot spots,” where plastics can readily find their way into waterways.While research about microplastic pollution has increased, there has not been a systematic approach or agreement on what pollutants should be measured. The ocean agency’s plan outlines shortcomings in the science that need to be corrected, so that pollution measures can be standardized and safety thresholds created.Microplastic pollution has drawn international attention. The United Nations is attempting to draft a treaty to rein in the contaminants, while the European Union is drawing up a policy of its own.The U.S. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine reported last year that America produced more plastic pollution, through 2016, than any other country, exceeding all the European Union nations combined.The California’s ocean agency’s action this week grew out of a 2018 law, authored by Sen. Anthony Portantino (D-La Canada Flintridge), that demanded state action.Officials at the state Water Resources Control Board are working on a separate policy to measure and set safety guidelines for the levels of microplastics that will be permissible in drinking water.The San Francisco Bay pollution study, co-authored by the San Francisco Estuary Institute, found that more than 7 trillion bits of plastic washed into the bay each year.Warner Chabot, executive director of the institute, praised state leaders for approving the microplastics plan.“Solving the problem requires that we stop or greatly reduce microplastics at their source,” Chabot said. “There is no quick fix and a range of options for a solution.”

Category Archives: Ocean

World must 'restrain demand' for plastic, OECD report says

Despite growing recognition that the world is making more plastic than it can handle, the petrochemical industry has kept churning out plastic products — to the detriment of the planet and the climate.

A report released on Tuesday by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, or OECD, offers a granular look at plastics’ life cycle, describing a system that dumps millions of tons of plastic waste into the environment every year. In 2019, before the COVID-19 pandemic began, the report found that only 9 percent of the world’s 353 million tons of plastic waste was recycled into new products. The rest was either burned, put in landfills, or “mismanaged” — dumped in uncontrolled sites, burned in open pits, or leaked into the environment.

The authors of the OECD’s first report on the world’s plastics called for countries to take urgent action to rein in the problem, including by scaling back demand for single-use plastics. “[T]he current linear model of mass plastics production, consumption, and disposal is unsustainable,” the report says.

The analysis comes just days ahead of a high-stakes United Nations summit, where world leaders are expected to begin drafting a global treaty on plastic pollution. The talks are backed by many of the world’s leading plastic producers, and advocates are hopeful that they will yield a binding agreement to address plastic’s full life cycle and restrain its production. Such an agreement would represent a major departure from the post-productions efforts — ocean cleanup initiatives, for example — that have for decades defined most plastic management strategies.

Part of the reason these approaches haven’t worked is because they are ill-equipped to keep up with the sheer amount of plastic the world produces. According to the OECD report, global plastic production has skyrocketed in the past two decades, outpacing economic growth by nearly 40 percent. By 2019, plastic production had doubled since 2000 and reached an eye-watering 460 million metric tons — about the same weight as 45,500 Eiffel Towers. This growth appears to be unstoppable; not even the Great Recession nor the COVID-19 pandemic managed to curb plastics use for long. In 2020, when the coronavirus first began shuttering economies and disrupting global supply chains, the use of plastic dipped a mere 2.2 percent below 2019 levels. The OECD says it is now “likely to rebound once again.”

Some of the top companies contributing to the planet’s glut of plastic are better known as oil and gas producers: ExxonMobil, Sinopec, Saudi Aramco. Anticipating a global shift to cleaner forms of energy, these firms have invested big in plastics that can be sold — and discarded — abroad.

Herons walk amid plastic waste at a Panama City beach.

Luis Acosta / AFP via Getty Images

These companies’ plans could inundate poorer parts of the world with plastic. They could also help raise global temperatures. In 2019, the report concluded, plastics generated 3.4 percent of the planet’s greenhouse gas emissions — mostly due to carbon-intensive processes needed to manufacture plastic from fossil fuels. This finding echoes previous work from the U.S.-based advocacy group Beyond Plastics, which, in a study published last October, called plastic “the new coal.” That study used federal data to suggest that the American plastics industry is on track to overtake coal in its contribution to climate change by 2030.

Beyond Plastics and other environmental advocates have long contended that this monumental scale of production is almost certainly unnecessary. According to the OECD’s analysis, 40 percent of the world’s plastic production in 2019 went toward packaging with an average useful lifetime of less than six months. Then, even if that plastic makes it into a controlled landfill — what many activists say is the least bad way to dispose of plastic waste — it can take hundreds of years to degrade. Other disposal methods like incineration emit toxic chemicals into the atmosphere. And so-called “leakage,” the release of plastics into waterways and ecosystems, can strangle wildlife and poison the food chain.

What can be done? The OECD recommended four key areas for intervention, including bolstering markets for recycled products and investing in “innovation” to extend the lifetimes of plastic goods. The organization also stressed the need for domestic policies to “restrain demand” for plastics, saying that “current bans and taxes are insufficient.” The organization recommended a suite of ideas that could make it more expensive for companies to churn out plastics: Fees could force companies to assume the costs of waste management and collection; governments could take away fossil fuel subsidies.

In response to Grist’s request for comment, Joshua Baca, vice president of plastics for the trade group the American Chemistry Council, said that plastic companies already supported many of the OECD’s recommendations, including recycled content standards and “improving access to waste collection.”

Carroll Muffett, president and CEO of the advocacy group Center for International Environmental Law, said that many of the OECD’s recommendations were well-intentioned, but wished the report had placed a greater emphasis on limiting plastic production. Characterizing plastic pollution as a mismanaged waste problem, he said, can distract decision-makers from policies designed to create less waste in the first place.

This is the point that hundreds of advocacy groups and scientists have been making in the lead-up to this month’s U.N. Environment Assembly meeting in Nairobi, Kenya. In December, more than 700 civil society groups, workers and trade unions, Indigenous peoples, women’s and youth groups, and others urged U.N. member states to craft a legally binding agreement that includes strategies to wind down global plastic production. Roughly 90 companies and more than 2 million individuals have made similar appeals.

“If you only focus on the demand side of the equation without addressing the expansion of that production capacity,” Muffett said, “then you are always chasing the problem and never catching it.”

Are microbes the future of recycling? It's complicated

Since the first factories began manufacturing polyester from petroleum in the 1950s, humans have produced an estimated 9.1 billion tons of plastic. Of the waste generated from that plastic, less than a tenth of that has been recycled, researchers estimate. About 12 percent has been incinerated, releasing dioxins and other carcinogens into the air. Most of the rest, a mass equivalent to about 35 million blue whales, has accumulated in landfills and in the natural environment. Plastic inhabits the oceans, building up in the guts of seagulls and great white sharks. It rains down, in tiny flecks, on cities and national parks. According to some research, from production to disposal, it is responsible for more greenhouse gas emissions than the aviation industry.

This pollution problem is made worse, experts say, by the fact that even the small share of plastic that does get recycled is destined to end up, sooner or later, in the trash heap. Conventional, thermomechanical recycling — in which old containers are ground into flakes, washed, melted down, and then reformed into new products — inevitably yields products that are more brittle, and less durable, than the starting material. At best, material from a plastic bottle might be recycled this way about three times before it becomes unusable. More likely, it will be “downcycled” into lower value materials like clothing and carpeting—materials that will eventually be disposed of in landfills.

“Thermomechanical recycling is not recycling,” said Alain Marty, chief science officer at Carbios, a French company that is developing alternatives to conventional recycling.

“At the end,” he added, “you have exactly the same quantity of plastic waste.”

Carbios is among a contingent of startups that are attempting to commercialize a type of chemical recycling known as depolymerization, which breaks down polymers — the chain-like molecules that make up a plastic — into their fundamental molecular building blocks, called monomers. Those monomers can then be reassembled into polymers that are, in terms of their physical properties, as good as new. In theory, proponents say, a single plastic bottle could be recycled this way until the end of time.

But some experts caution that depolymerization and other forms of chemical recycling may face many of the same issues that already plague the recycling industry, including competition from cheap virgin plastics made from petroleum feedstocks. They say that to curb the tide of plastic flooding landfills and the oceans, what’s most needed is not new recycling technologies but stronger regulations on plastic producers — and stronger incentives to make use of the recycling technologies that already exist.

Buoyed by potentially lucrative corporate partnerships and tightening European restrictions on plastic producers, however, Carbios is pressing forward with its vision of a circular plastic economy — one that does not require the extraction of petroleum to make new plastics. Underlying the company’s approach is a technology that remains unconventional in the realm of recycling: genetically modified enzymes.

Enzymes catalyze chemical reactions inside organisms. In the human body, for example, enzymes can convert starches into sugars and proteins into amino acids. For the past several years, Carbios has been refining a method that uses an enzyme found in a microorganism to convert polyethylene terephthalate (PET), a common ingredient in textiles and plastic bottles, into its constituent monomers, terephthalic acid, and mono ethylene glycol.

Although scientists have known about the existence of plastic-eating enzymes for years — and Marty says Carbios has been working on enzymatic recycling technology since its founding in 2011 — a discovery made six years ago outside a bottle-recycling factory in Sakai, Japan helped to energize the field. There, a group led by researchers at the Kyoto Institute of Technology and Keio University found a single bacterial species, Ideonella sakaiensis, that could both break down PET and use it for food. The microbe harbored a pair of enzymes that, together, could cleave the molecular bonds that hold together PET. In the wake of the discovery, other research groups identified other enzymes capable of performing the same feat.

Enzymatic recycling’s promise isn’t limited to PET; the approach can potentially be applied to other plastics, including polyurethane, used in in foam, insulation, and paint. But PET offers perhaps the most expansive commercial opportunity: It is one of the largest categories of plastics produced, widely used in food packaging and fabrics. PET-based beverage bottles are among the easiest plastics to collect and recycle into a marketable product.

Alain Marty, scientific director of Carbios, attends the inauguration of the company’s demonstration facility in Clermont-Ferrand, France, in September 2021.

Visual: Thierry Zoccolan/AFP via Getty Images

Traditional depolymerization technologies rely on inorganic catalysts rather than enzymes. But some chemical recycling companies have struggled in efforts to turn PET recycling into a viable business model — with some even facing legal scrutiny.

Despite this, Marty says that Carbios’ enzyme-based approach offers advantages over traditional depolymerization methods: The enzymes are more chemically selective than synthetic catalysts — they can more precisely target specific sites on specific molecules — and could therefore yield purer product. Plus they work at relatively low reactor temperatures and do not require expensive, hazardous solvents.

Traditionally, however, the problem with enzymes has been that they work slowly and can destabilize under heat. In early experiments, it sometimes took weeks to process just a fraction of a batch of PET. In 2020, Marty and colleagues at Carbios, along with researchers in France, announced that they had engineered an enzyme — a so-called cutinase, naturally found in microbes that decompose leaves — that could withstand warmer temperatures and convert nearly an entire batch of PET into monomers in a matter of hours. The discovery dramatically boosted enzymatic recycling’s commercial prospects; In the 10 months that followed, Carbios’ stock price on the Euronext Paris exchange grew about eightfold.

Last September, Carbios began testing its technology at a demonstration facility near its headquarters in Clermont-Ferrand, France, about a two-hour drive west of Lyon. Used PET arrives here as thin, pre-processed flakes about one-fifth of an inch across. In a 16-foot-tall reactor, the flakes are mixed with the patented cutinase enzymes —produced by Denmark-based biotechnology company Novozymes — and warmed to a little above 140 degrees Fahrenheit. Within 10 hours, Marty says, 95 percent of the plastic fed to the reactor, the equivalent of 100,000 plastic bottles, can be converted into monomers, which are then filtered, purified, and prepared for use in plastic manufacturing. (The remaining 5 percent, made up of unreacted plastic and impurities, is incinerated.) As Marty describes it, the end product is physically indistinguishable from the petrochemical-based substances used to manufacture virgin PET.

Carbios’ recycling technology has grabbed the attention of some of the world’s largest consumer goods companies. L’Oréal, Nestlé, and PepsiCo have collaborated with the startup to produce proof-of-concept bottles, and all seem intent on eventually putting enzyme-recycled plastic on shelves.

But Kate Bailey, the policy and research director at Eco-Cycle, a nonprofit recycler based in Colorado, says that over her 20 years in the recycling industry, she has grown skeptical of biotechnology fixes like the one being touted by Carbios. While she acknowledges that new solutions are needed, given the urgency of the plastic problem, she says “we don’t have more years to figure this out and wait for new technology.” Bailey points to lingering questions about how enzymatic recycling will be scaled up to handle commercial volumes, including questions about its energy footprint and its handling of toxic chemical additives found in many consumer plastics.

Marty concedes that Carbios’ process is, indeed, more energy-intensive than conventional recycling — he declined to specify by how much — but added that it’s not fair to compare enzymatic recycling with thermomechanical processes, which don’t produce as high quality of a recycled product and eventually result in the same quantity of waste. Still, he said, it requires less energy, and releases less greenhouse gas, than producing virgin PET from petroleum — claims that are supported by an independent analysis published last year by the U.S. National Renewable Energy Laboratory. As for additives, he says they are filtered out during post-reaction processing and incinerated.

In the Carbios laboratory, several plastic samples sit on the lab bench.

Visual: Thierry Zoccolan/AFP via Getty Images

A small-scale reactor mixes plastic and enzymes in the Carbios laboratory.

Visual: Thierry Zoccolan/AFP via Getty Images

In the Carbios demonstration plant, PET flakes and the patented cutinase enzymes mix in the large reactor tank on the right. Within 10 hours, 95 percent of the plastic is converted into monomers, Marty says.

Visual: Carbios

But the most stubborn hurdle for Carbios and other enzymatic recycling hopefuls may be an economic one. “It’s super cheap to make virgin plastic, especially with the low price of oil,” said Bailey.

“You have to be able to sell your recycled PET against to some company that also has the option of buying virgin PET,” she added, “and when virgin is just cheaper, then that’s what companies buy.”

In its analysis, the National Renewable Energy Laboratory estimated that PET monomers produced through enzymatic recycling would carry a price of at least $1.93 per kilogram; virgin, petroleum-based monomers have ranged between $0.90 and $1.50 per kilogram since 2010. And now that many fossil fuel companies are pivoting their business models toward plastic production, the market competition for plastic recyclers could grow even stiffer.

Marty, however, is optimistic about his company’s prospects. He points out that the price of oil is rising and that tightening regulations on the use of fossil fuels in Europe is making recycled plastic more competitive there. Several consumer goods giants have publicly committed to sourcing more of their products from recycled materials: Coca-Cola pledged to use recycled material for half of its packaging by 2030, and Unilever aims to cut its reliance on virgin plastic in half by 2025.

“At the beginning, sure, it will be a little more costly,” Marty said. “But we will reduce, with experience, the cost of this recycled PET.”

Wolfgang Streit, a microbiologist at the University of Hamburg, says that even if companies achieve commercial success with PET, some polymers may never be amenable to the enzymatic recycling. Polymers like polyvinylchloride, used in PVC pipes, and polystyrene, used in Styrofoam, are held together by powerful carbon-carbon bonds, which might be too sturdy for enzymes to overcome, he explains.

That’s one reason Bailey believes new policies need to be considered alongside new technologies in addressing the global plastic waste problem. She advocates for measures that limit the production of hard-to-recycle plastics and improve collection rates for materials like PET, which can be recycled, albeit imperfectly, with existing technologies. Bailey notes that currently only about three in 10 PET bottles gets collected for recycling. She describes that as low-hanging fruit “that we could solve today with proven technology and policies.”

Now that many fossil fuel companies are pivoting their business models toward plastic production, the market competition for plastic recyclers could grow even stiffer.

Most PET produced globally is used not for bottles but for textile fibers, which, because they often contain blended materials, are rarely recycled at all. Mats Linder, the head of the consulting arm of Stena Recycling in Sweden, said he’d like to see chemical recycling technologies focus on these and other parts of the recycling industry where conventional recycling is coming up short.

As it happens, Carbios is working to do just that, Marty says. The French company Michelin has validated the company’s technology, which could allow it to recycle used textiles and bottles into tire fibers. It aims to launch a textile recycling operation in 2023, and Marty says the company is on track to launch a 44,000-ton-capacity industrial scale facility in 2025.

Gregg Beckham, a senior research fellow at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory, believes the global plastic problem will call for a diverse mix of technological and policy solutions, but he says enzymatic recycling and other chemical recycling technologies are advancing rapidly, and he’s optimistic that they will have a role to play. “I think chemical recycling is useful in the contexts where other solutions don’t work,” he said. “And there are many places where other solutions don’t work.”

Ula Chrobak is a freelance science writer based in Nevada. You can find more of her work at her website.

Ocean plastic is bad, but soil plastic pollution may be worse

Those concerned with agricultural plastics in the soil are looking to address the problem from several fronts.Acknowledging that there is no silver bullet, the FAO report outlines a variety of recommendations that span several different policy arenas, including eliminating the use of the most problematic agricultural plastics, investing in biodegradable substitutes, and mandatory extended producer responsibility obligations for appropriate end-of-life management. The authors of the report also suggest establishing an international, voluntary code of conduct on sustainable use, which will be discussed by the FAO’s Committee on Agriculture in July, said Thompson, one of the report’s authors.“A voluntary code can have a much wider scope, because it doesn’t require consensus between all the countries that are debating it,” said Thompson. “It can set responsibilities for a wider range of stakeholders rather than just national governments.”“There are links between the climate crisis, plastics, biodiversity, and toxics. They are all part of the same story.”The report also supports mandated solutions. Carlini and her colleagues, for example, are gearing up for negotiations on drafted resolutions for a global, legally binding plastics treaty at the U.N. Environment Assembly (UNEA) in Nairobi this month. While countries joined together at UNEA in 2019 and previous sessions to pass a resolution on marine plastic pollution, Carlini is advocating for policymakers to take a broader approach.“We’re extracting fossil fuels and using them to make chemicals and pesticides and plastics that are then polluting the world,” said Carlini. “There are links between the climate crisis, plastics, biodiversity, and toxics. They are all part of the same story.”Meanwhile, Nizzetto is working with PAPILLIONS, a research project supported by the European Commission to study the lifecycle of agricultural plastics and their long-term impacts. The group is calling on policymakers to establish sustainability criteria for agricultural plastics, including biodegradability standards, life-cycle traceability, and increased funding for research that investigates the complex interactions among plastics and other pollutants in soils, including pesticides and heavy metals.In the U.S., potential solutions to address agricultural plastics have been slower to develop.The FAO report emphasizes solutions that embrace the “polluter pays” principle, including Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) schemes that promote closed-loop recycling of agricultural plastics, funded by the corporations that produce them. With a mandated EPR system, the producers of agricultural plastics would be responsible for funding and developing the infrastructure needed to collect and recycle those materials based on government regulations that outline sustainable management.“If the corporation is required to pay for end-of-life disposal and it’s costly, they will be incentivized to reduce the toxins in their products or design them for recyclability,” said Suna Bayrakal, director of policy and programs at the Boston-based Product Stewardship Institute. “EPR laws shift the financial and management responsibility to the producers, all while retaining government oversight.”EPR programs currently exist in 33 states and Washington, D.C. for a variety of products like batteries, paint, pharmaceuticals, and tires. Last year, Maine and Oregon passed the first-ever U.S. EPR laws to require companies that put consumer packaging on the market to contribute to the costs of collection and recycling. But few of these mandates cover agricultural plastics, aside from California’s recycling program for pesticide containers of 55 gallons or less.

How a dramatic win in plastic waste case may curb ocean pollution

POINT COMFORT, TEXASNearly every day for three years, Diane Wilson and a handful of fellow volunteers spent hours poking through the buggy, marshy grasses of the Gulf Coast, combing stretches of pebbly sand, or kayaking beside a huge petrochemical plant, all in search of tiny plastic pellets called nurdles. They found the lentil-sized pieces everywhere, filling gallon bags with them, and submerging bottles to collect water tainted with raw plastic powder.In March of 2019, Wilson, a retired shrimp boat captain and fisherwoman, loaded a trailer with 2,400 of those samples—46 million individual pellets, she estimates—and drove her pickup truck to federal court to face down Formosa Plastics, the company responsible for the spills. The victory she won there led to what is said to be the largest ever settlement of a private citizen’s Clean Water Act lawsuit. It was a big moment in efforts to confront a type of pollution that, while accounting for a significant chunk of the microplastics choking the world’s seas, gets far less attention than the more visible tide of bottles, bags, and other post-consumer waste.Now, Wilson’s win is a warning to others making and handling nurdles that they too could face costly consequences for leaking plastics into the environment. Regulation of the pellets remains weak, but the ripples of change the case set off may be the start of a new, more stringent approach to managing them.Nurdles are the building blocks for all manner of plastic products, from yogurt containers and toothpaste tubes to car parts. Every year, Formosa’s plant turns by-products of oil and gas into millions of tons of those pellets, and plastic powder, a raw form of vinyl. The voluminous evidence Wilson’s group gathered persuaded the judge hearing her case that the complex was discharging a flood of the plastics into Cox Creek and Lavaca Bay, part of an interconnecting network of Gulf of Mexico inlets about halfway between Houston and Corpus Christi.The judge’s ruling called Formosa a “serial offender” whose “violations are enormous.” Following the verdict, the company, part of Taiwan-based Formosa Plastics Group—the world’s sixth largest chemical maker—agreed to pay $50 million into a trust funding local conservation projects, scientific research, and a sustainable fishing co-operative. Formosa also committed to stopping the spills and cleaning up its mess.Those costs have gotten the attention of executives elsewhere in the industry, says Karen Hansen, a lawyer in the Austin, Texas, office of the firm Beveridge & Diamond, who represents companies on water quality issues. “No company wants the liability that Formosa Plastics found itself with,” so others are now working to reduce their own nurdle leaks, she says.Wilson thinks her case is a powerful model: citizen science and activism holding a major polluter to account, and citizen enforcement making the changes stick. Hansen agrees: “The reverberations have been far-reaching.”Mind-boggling numbers The problem is not just plastic manufacturers. “Transporters, distributors—the entire supply chain” is losing pellets, says Jace Tunnell, a marine biologist with the University of Texas at Austin’s Marine Science Institute. Nurdles often spill while being loaded on and off trains. They accumulate on tracks and then wash toward rivers, lakes, or coastlines when it rains, says Tunnell, who founded Nurdle Patrol, a citizen science project awarded a $1 million grant from Wilson’s trust.The numbers are mind-boggling. One study estimated that in the United Kingdom, between five and 53 billion pellets are lost into the environment each year. In 2020 more than 700 million spilled from a cargo ship on the Mississippi River near New Orleans. In Sri Lanka, pellets are still washing up on hundreds of miles of coastline after a container ship carrying 1,700 metric tons sank last year; the UN called it the biggest plastic spill on record.Overall, a 2016 report estimated, 230,000 metric tons of nurdles enter the world’s oceans each year, accounting for 24 percent of spilled microplastics and nearly 2 percent of total marine plastics.Diane Wilson holds up plastic pieces she pulled from dirt on the bank of a waterway outside the Formosa Plastics plant in Point Comfort, Texas, on November 3, 2021.Photograph by Mark Felix, AFP/Getty ImagesPlease be respectful of copyright. Unauthorized use is prohibited.Even as public awareness about plastic pollution grows, fossil fuel companies and their petrochemical subsidiaries are ramping up to make more plastic than ever in the years to come. The industry—anticipating that action on climate change may reduce demand for oil and gas—sees plastic as a promising source of revenue growth. So without action to address nurdle spills, they could get even more frequent and more damaging.The industry’s expansion is well underway on the Gulf Coast, long the hub for U.S. plastic production, with new plants opening and old ones growing. ExxonMobil and the Saudi petrochemical conglomerate SABIC just jointly fired up a giant new complex near Corpus Christi. Formosa recently completed a $5 billion expansion of the plant at the center of the nurdle case. Even before it was done, one of the company’s lawyers said the complex was producing a trillion pellets a day.Last year, in the wake of Wilson’s win, the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, the state regulator, tightened requirements for companies making and handling nurdles. Neil McQueen, of the Surfrider Foundation, an environmental group, says the new language is too vague, and leaves industry wiggle room to define terms to its advantage. Hansen says companies anticipate tougher enforcement and are acting accordingly.Elsewhere, other activists are following Wilson’s lead, stepping in where regulators have failed to act. South Carolina environmentalists started collecting nurdles around Charleston Harbor after the Formosa verdict. Last year, they won a $1 million settlement—and an agreement to make changes to prevent future spills—from Frontier Logistics, a plastics distribution company.‘It was going right into the creek’Wilson is the fourth generation in her family to have earned a living on the waters tucked behind barrier islands on the Matagorda Bay system. The area’s once-rich habitats—a haven for more than 400 bird species and home to dolphins, alligators, and sea turtles—have been declining for decades, a result of development, industrial pollution, and threats such as algal blooms. That, and a growing awareness of petrochemicals’ toxic footprint, spurred Wilson to become an environmental activist more than 30 years ago.Her focus on nurdles began in 2012, when a former Formosa employee told her the plant was losing significant quantities. At first, Wilson tried to prod state regulators to do something. The agency sent inspectors, and later fined Formosa $122,000, but Wilson could see that its actions wouldn’t stop the spills.So in January 2016 she and a few others began what became near-daily nurdle- and powder-collecting outings, under the auspices of San Antonio Bay Estuarine Waterkeeper, a group she leads. “We started wading out on the bay,” Wilson tells me as we sit outside her little purple house, underneath a tree with Spanish moss draped over its thick, twisting branches. “Along the shores, around the boat ramps.” Once they figured out where to look, the pellets were easy to see, “and they’re everywhere.”She bought a cheap kayak and started paddling on Cox Creek, which meanders right past Formosa’s 2,500-acre complex. She found one of the discharge points, a ditch “coming right from the plant. And it was going right to the fence, and it was going right into the creek,” she says. In one spot nearby, pellets carpeted the marshy shore, “like that deep,” she told me, holding her hands about five inches apart.The volume and meticulous documentation of the samples her group gathered, plus hundreds of photos and videos, enabled Wilson’s lawyers to refute one of Formosa’s main arguments—that any plastics it discharged were only “trace” amounts, allowed by its permit. While questioning one of the company’s expert witnesses, “he was talking about ‘trace,’ and I had a video of Diane in a kayak on the creek,” says Amy Johnson, one of Wilson’s lawyers. “And all around her is a bed of plastics floating on the water, probably five or 10 feet out,” she recalls. “We all know that’s not a trace amount.”Holding Formosa to account In the end, U.S. District Judge Kenneth Hoyt found there were 736 days of illegal releases at one of Formosa’s discharge points, and 1,149 at a group of eight others. Lawyers hashed out a consent decree that gives Wilson an unusual degree of involvement in holding Formosa to its commitments. Her team scrutinizes the company’s plans for removing old pellets and stopping fresh discharges, and she can challenge any of it in court. Formosa pays for her lawyers and an engineering expert. Meanwhile, an independent monitor tracks new spills. The company is fined $25,000 a day, per body of water, for each violation. Since the settlement, it’s racked up nearly $4 million in new fines, payable to the trust.The Formosa Plastics plant in Point Comfort, Texas. Formosa set up shop in 1983 south of Houston in Point Comfort. Over the years, the plant has polluted the surrounding waters with tiny plastics and plastic powder.Photograph by Mark Felix, AFP/Getty ImagesPlease be respectful of copyright. Unauthorized use is prohibited. Formosa said in an email that its plant had not discharged any nurdles since November, and was working toward eliminating loss of smaller plastics, but had no estimate of current powder discharges. “Reaching zero visible plastics loss is a priority for the company,” its statement said, adding that Formosa participates in Operation Clean Sweep, a voluntary industry program to reduce plastic discharges.Johnson says the fixes Formosa has made so far are superficial measures such as filters, not the more fundamental changes needed inside the plant. In the last quarter of 2021, the monitor logged violations on 78 out of 91 days.While the scale of Wilson’s evidence collection is unusual, the “citizen suit” has long been key to American environmental enforcement. Environmentalists now worry the Supreme Court may tighten eligibility to sue in such cases, making it harder for individuals to challenge big polluters.‘You’ll never get through counting them’Meanwhile, the trust’s money is being disbursed. The biggest initiative, at $20 million, is the creation of a sustainable fishing cooperative. A Georgia-based federation of Black farming cooperatives oversees the project, aiming to revitalize the bays’ ecosystems so small fishermen and shrimpers have a future. Other grants fund beach restoration, the creation of a park, and kids’ environmental education at YMCA camps.Funding scientific research is another focus of the trust. Tunnell’s Nurdle Patrol has more than 5,000 volunteers, who have done 11,000 pellet surveys. The metric they use is how many nurdles one person can gather by hand in 10 minutes; participants scoop as many as they can, count them afterwards, and report the results.After Tunnell vets the data, it’s plotted on a map. “Now you overlay it with where the manufacturers are—boom, it matches up,” he says. Around New Orleans and through the Mississippi River Delta cluster dots of red (meaning 101 to 1,000 nurdles collected) and purple (more than 1,000 nurdles). The petrochemical hub around Houston is crowded with purple, and a steady line of red and orange (31 to 100 nurdles) goes right down to Mexico.Data is trickling in from elsewhere in the country, and it offers a glimpse of nurdles’ reach—reds on the Great Lakes; near Philadelphia and Trenton, New Jersey; around Charleston, South Carolina; and in the Pacific Northwest. Only one state, California, bars nurdle discharges, Tunnell says. Nurdle Patrol encourages participants to use their data to push political leaders for tighter regulations.Researchers are also studying the harm nurdles wreak. Birds and sea creatures can choke or suffer internal damage when they ingest pellets, or starve with stomachs full of plastic. Another worry is the chemicals that attach themselves to floating pellets. Dangerous toxins, including mercury, the long-outlawed pesticide DDT, and a group of hazardous industrial chemicals called PCBs have all been found on nurdles.Near the Formosa plant, Wilson’s volunteers are still out looking for plastic. On a baking day in August 2021, Ronnie Hamrick, a retired Formosa worker, takes me to a little stretch of beach near a bait stand, where a layer of white scum coats the water. “This whole bay is totally like this,” he says. “You got kids swimming in it.”Later, across a two-lane highway from the plant, I follow him down a steep embankment to the edge of Cox Creek. Mopping sweat from his face, he pulls aside thick clumps of vegetation with a rake. In the little puddle it exposes, maybe 10 inches square, hundreds of white pellets float to the surface.Everywhere Hamrick probes, there are more nurdles—a hint of how hard it will be to clean up this mess without irrevocably damaging the ecosystem. He pulls out a plant and holds it up to show me the pellets laced densely through the root system, like tiny eggs. “I’ll get you more over here, I see a bunch of them,” he tells me. When I ask Hamrick how many nurdles he guesses are in a particular spot, his reply is a reminder of the sheer volume of Formosa’s spills. So many, he answers sadly, that “you’ll never get through counting them.”Reporting for this story was supported by the McGraw Fellowship for Business Journalism at the City University of New York’s Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism. Beth Gardiner is the author of Choked: Life and Breath in the Age of Air Pollution.

Global plastic consumption has quadrupled in 3 decades, says OECD

Paris, Feb 22 (EFE).- Plastic consumption has quadrupled over the past three decades while its production has doubled from 2000 to 2019 to reach 460 million tonnes, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) said Tuesday.

The OECD warned that plastics account for 3.4 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions since the bulk of its waste ends up in landfills, incinerated, or leaking into the environment.

In its first outlook study on plastic, the organization called for “greater use of instruments” like extended producer responsibility schemes for packaging and durables, landfill taxes, deposit-refund, and Pay-as-You-Throw systems.

The OECD report said that global plastic waste generation reached 353 million tonnes from 2000 to 2019.

“Nearly two-thirds of plastic waste comes from plastics with lifetimes of under five years, with 40 percent coming from packaging, 12 percent from consumer goods, and 11 percent from clothing and textiles,” the report said.

The report says only nine percent of plastic waste was recycled, even as 15 percent goes for recycling.

“But 40 percent of that is disposed of as residues. Another 19 percent is incinerated, 50 percent ends up in landfill and 22 percent evades waste management systems and goes into uncontrolled dumpsites, is burned in open pits or ends up in terrestrial or aquatic environments, especially in poorer countries.”

In 2019, 6.1 million tonnes of plastic waste leaked into aquatic environments, and 1.7 million tonnes flowed into oceans, said the report.

“There is now an estimated 30 million tonnes of plastic waste in seas and oceans, and a further 109 million tonnes has accumulated in rivers. The build-up of plastics in rivers implies that leakage into the ocean will continue for decades to come, even if mismanaged plastic waste could be significantly reduced.”

The report noted that almost half of all plastic waste is generated in OECD countries even as the waste generated annually per person varies from 221 kg in the United States and 114 kg in European OECD countries to 69 kg, on average, for Japan and South Korea.

Most plastic pollution comes from inadequate collection and disposal of larger plastic debris known as macro-plastics.

But the leakage of microplastics (synthetic polymers smaller than 5 mm in diameter) from things like industrial plastic pellets, synthetic textiles, road markings, and tire wear is also a serious concern.

The OECD said more needed to be done to create a separate and well-functioning market for recycled plastics, still viewed as substitutes for virgin plastic.

Setting recycled content targets and investing in improved recycling technologies could help to make secondary markets more competitive and profitable, it said.

The report, published on the eve of the UN talks to reduce plastic waste, found that the Covid-19 crisis has led to a 2.2 percent decrease in plastic use in 2020 as economic activity slowed.

But it noted a rise in littering, food takeaway packaging, and plastic medical equipment like masks had driven up littering.

“As economic activity resumed in 2021, plastics consumption has also rebounded,” it said. EFE

ac-ssk

Refillable soda bottles used to be the norm. Can they come back?

Coca-Cola says that by the end of the decade it will sell a quarter of its drinks in refillable packaging—a big step toward curbing plastic pollution. What would it take to have refillable bottles everywhere?

[Photos: somchaisom/iStock/Getty Images Plus, RobinOlim/iStock/Getty Images Plus, apomares/iStock/Getty Images Plus]

By

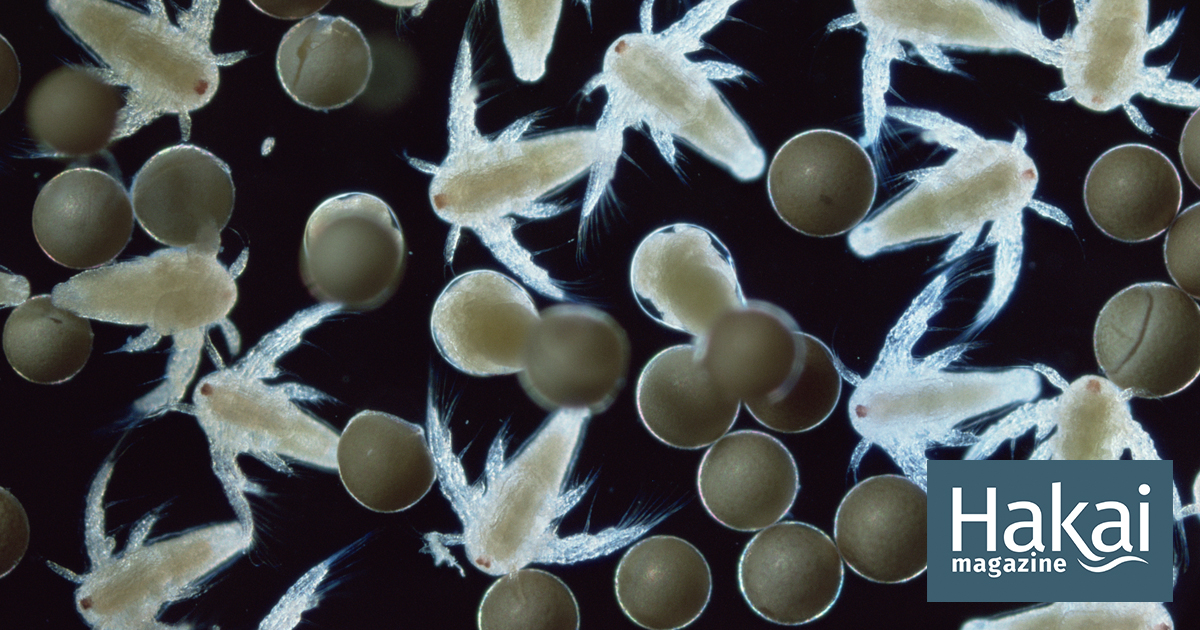

Scientists can spy shrimp eggs from space

Article body copy

It’s become a bit clichéd to say with surprise that something—a wildfire, the Great Barrier Reef, a ship blocking the Suez Canal—can be seen from space. But every so often, scientists manage to spot something from space that truly is surprising. Case in point: University of South Florida optical oceanographer Chuanmin Hu and his colleagues have worked out ways of spotting aggregations of small floating objects, such as shrimp eggs, algae, and herring spawn, from space. And not only can they find these buoyant masses—they can tell you which is which.

Hu and his team can’t zoom in on a satellite image enough to actually see a shrimp egg in the way that you could look at the picture and say, “That’s a shrimp egg!” So how can they tell the difference?

The key to identifying the objects, says Hu, is that “every floating matter has its fingerprint.”

Different objects, being made of different materials, reflect characteristic wavelengths of light—patterns that scientists can read using multispectral instruments mounted on satellites. Using these patterns to identify substances is known as spectroscopy. The technique is common in labs, and scientists in the rapidly evolving field of remote sensing are carrying it over into satellite analysis.

Hu and his team, along with scientists around the world, are building a knowledge base of what different objects and materials look like from space. That way, when they come across an unfamiliar floating object on a satellite image, they can look to see whether the wavelengths it reflects match up with anything that’s been analyzed before.

Sometimes Hu and his colleagues can only speculate about the identity of floating matter until they have a chance to take a close-up look. A trip to Utah’s Great Salt Lake, for example, confirmed their suspicion that filamentous white slicks they’d seen on satellite images were massive accumulations of brine shrimp eggs. Over the past year, Hu’s team has also published a method for identifying herring spawn, and they are attempting to identify sea snot—the disgusting films of phytoplankton mucus that plagued Turkey last summer.

But there’s also a pressing problem that scientists hope remote sensing can address—the vast amounts of plastic that are clogging the oceans.

“The main idea is to create an algorithm that can detect the plastic litter,” says Konstantinos Topouzelis, an environmental scientist at the University of the Aegean in Greece. “So the cleaning efforts can be guided.”

But identifying plastic from space comes with challenges. For one, there are many kinds of plastic, and some blend in with the surrounding water. Plastic also aggregates and disperses quickly. And while some aggregations are huge, like the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, many are small and difficult to pick out in the images.

For the past few years, Topouzelis and his students have been deploying and analyzing targets, such as shopping bags and fishing nets, made of various plastic materials. The spectral signatures of these known plastics give researchers a starting point when they’re wondering whether the swirls and swooshes on other satellite images might be plastic.

Oceanographer Katerina Kikaki, at the National Technical University of Athens in Greece, is taking a different approach. She and her colleagues have scoured through seven years of scientific publications, records from citizen scientists, and media reports to find examples of plastic pollution. They recently published a database of satellite images that correspond to these known plastic accumulations. “Our data set can enable the community to explore the spectral behavior of plastic debris,” Kikaki says.

Kikaki’s and Topouzelis’s studies are examples of ground truthing—analyses of known objects that help confirm if remote assessments are accurate.

Having eyes on the ground can really help drive the field forward. Just looking at satellite observations, “my view is narrowed,” Hu says. “I may ponder over [a satellite image] for weeks or months.” But if a boat captain tweets a picture of sea snot along with some geographical information, that can save Hu a lot of time.

So if you’re on the water, and you stop to appreciate some mysterious slime, put it on social media! An optical oceanographer may be staring at a picture of the same region, wondering what’s out there.

Plastic pollution in oceans on track to rise for decades

BERLIN (AP) — Plastic pollution at sea is reaching worrying levels and will continue to grow even if significant action is taken now to stop such waste from reaching the world’s oceans, according to a review of hundreds of academic studies.The review by Germany’s Alfred Wegener Institute, commissioned by environmental campaign group WWF, examined almost 2,600 research papers on the topic to provide an overview ahead of a United Nations meeting later this month.“We find it in the deepest ocean trenches, at the sea surface and in Arctic sea ice,” said biologist Melanie Bergmann who co-authored the study, which was published Tuesday

Plastics clampdown is key to climate change fight, EU environment chief says

A volunteer shows ear sticks and plastics after a garbage collection, ahead of World Environment Day on La Costilla Beach, on the coast of the Atlantic Ocean in Rota, Spain June 2, 2018. REUTERS/Jon NazcaRegister now for FREE unlimited access to Reuters.comRegisterBRUSSELS, Feb 1 (Reuters) – Progressive reduction of fossil fuel-based plastics is crucial to tackling climate change, the EU’s top environmental official said, ahead of a United Nations meeting to launch talks on a world-first treaty to combat plastic pollution.Plastics production is becoming a key growth area for the oil industry as countries seek to shift away from polluting energy sources, but plastic waste is piling up in the world’s oceans and urban waterways and choking its wildlife. read more Last month, a study of ice cores revealed traces of nanoplastics in both polar regions for the first time.Register now for FREE unlimited access to Reuters.comRegister”The biggest topic is, at the end of the day, oil use for plastic production,” said EU Environment Commissioner Virginijus Sinkevicius amid preparations for the U.N. Environment Assembly summit starting in Nairobi on Feb. 28.”If we want to reach our decarbonisation goals for 2050, clearly we have to decrease steadily the use of fossil fuels, and one of the areas here as well is plastics,” he told Reuters in an interview.Sinkevicius said restricting virgin plastic production was “inevitably an important part” of a global treaty, but it was not yet clear what binding or voluntary requirements would be agreed.”I believe in binding measures more, but of course we’ll have to see what our international partners have to say,” he said.Petrochemicals, the fossil fuel-based building blocks for products including plastics and fertilisers, are expected to account for more than a third of global oil demand growth by 2030, according to the International Energy Agency.Consumer brands including Coca Cola (KO.N) and PepsiCo (PEP.O) have said the UN pact should include cuts in plastic production, although that could face resistance from oil and chemical firms and major plastic-producing countries like the United States.Other options for the UN deal could include improving waste collection and recycling, or developing plastics that are easier to reuse – although Sinkevicius said recycling alone could not rein in the plastic pollution crisis.”There’s no way that with this increased waste pile-up, that we will recycle our way out of it,” he said.The 27-country EU banned single-use plastic items such as cutlery and straws n 2021. France went further this year, banning plastic packaging for nearly all fruit and vegetables.(This story refiles to remove superfluous word ‘as’ from second paragraph)Register now for FREE unlimited access to Reuters.comRegisterReporting by Kate Abnett; additional reporting by Valerie Volcovici; editing by Philip Blenkinsop and John StonestreetOur Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles.