Picture a raft of sea ice in the Arctic Ocean, and you’re probably imagining a pristine marriage of white and blue. But during summertime, below the surface, something much greener and goopier lurks. A type of algae, Melosira arctica, grows in large, dangling masses and curtains that cling to the underside of Arctic sea ice, mostly obscured from a bird’s eye view.The algae, made up of long strings and clumps of single-celled organisms called diatoms, is an essential player in the polar ecosystem. It’s food for zooplankton, which in turn nourish everything from fish to birds to seals to whales — either directly or through an indirect, upwards cascade along the Pac-Man-esque chain of life. In the deep ocean, benthic critters also rely on making meals out of blobs of sunken algae. By one assessment, M. arctica accounted for about 45% of Arctic primary production in 2012. In short: the algae supports the entire food web.But in the hidden, slimy world of under-ice scum, something else is abundant: microplastics. Researchers have documented alarmingly high concentrations of teeny tiny plastic particles inside samples of M. arctica, according to a new study published Friday in the journal Environmental Science & Technology. The work adds to the growing body of evidence that microplastics are truly everywhere: in freshly fallen Antarctic snow, the air, baby poop, our blood — everywhere.

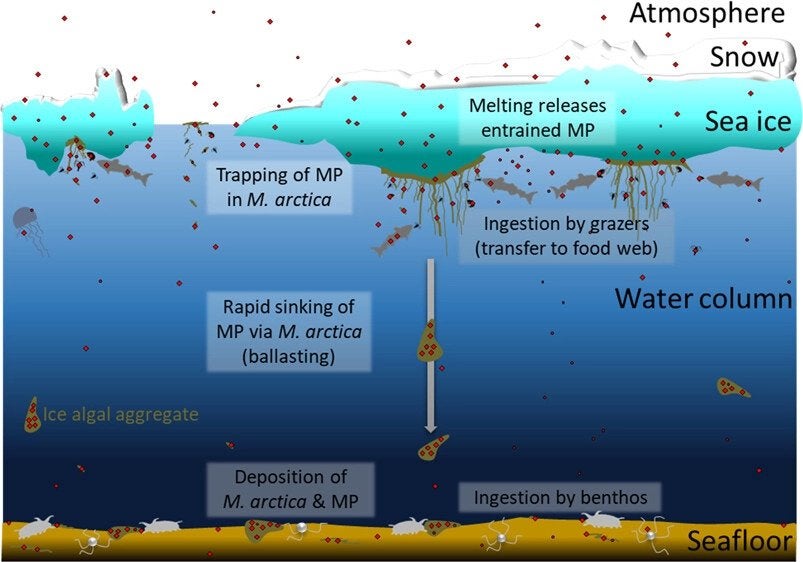

All 12 samples of algae the scientists collected from ice floes contained microplastics. In total, they counted about 400 individual plastic bits in the algae they examined. Extrapolating that to a concentration by volume, the researchers estimate that every cubic metre of M. arctica contains 31,000 microplastic particles — greater that 10 times the concentration they detected in the surrounding sea water. It could be bad news for the algae, the organisms that rely on it, and even the climate.Though microplastics are seemingly ubiquitous, the findings were still doubly surprising to Melanie Bergmann, the lead study author and a biologist at the Alfred Wegener Institute in Bremerhaven, Germany. In an email, she told Gizmodo she hadn’t expected to document such high levels of microplastics in M. arctica, nor for those concentrations to be so much higher than what was in the water. But in retrospect, the gummy nature of the algae probably explains it.Sea ice itself contains a lot of microplasitcs (up to millions of particles per cubic metre, depending on location, according to earlier research Bergmann worked on). Sea ice both sequesters plastic from the ocean through its freeze/melt cycle and collects the pollution from above as it is deposited by wind currents. In turn, that sea ice contamination likely trickles down to the algae. “When the sea ice melts in spring, microplastic probably becomes trapped [by] their sticky surface,” Bergmann hypothesizes. And both ice floes and their attached algal masses move around, scooping up plastic particles as they follow ocean currents.

Within the Arctic marine ecosystem, previous research has found the highest levels of microplastics in seafloor sediments, the biologist further explained. The algae cycle may explain a large part of those plastic deposits. By getting trapped in a gunky web of M. arctica filaments, the minuscule bits of manmade trash are actually hitching an express ride to the bottom of the ocean. Large chunks of algae sink much faster than tiny bits of debris on their own, which are more likely to remain suspended in the water column. So, on the bright side, the new study solves something of a mystery. But the benefit of novel knowledge may be the only silver lining here.Because the algae is the scaffolding of an Arctic food web, everything that eats it (or eats something that eats it) is almost certainly ingesting all of the plastic bits contained within. The health impacts of microplastics aren’t yet well established, but some early studies suggest they’re probably not good for people or wildlife. In this way, M. arctica’s sticky affinity for plastic could be slowly poisoning the entire ecosystem.

Then, there’s the way the pollution could be hurting the algae itself. Laboratory experiments of other algal species have shown that microplastics can hinder an organism’s ability to photosynthesize and damage algal cells. “We don’t yet know how widely this occurs amongst different algae and if this also affects ice algae,” said Bergmann; the impact of microplastics seems to vary a lot by species, she added.But in the era of climate change, any additional stress on already rapidly changing Arctic systems is unwelcome. And, if algae is indeed less able to photosynthesize when it’s stuffed with plastic, then it’s also less able to sequester carbon and less able to mitigate climate change — a small but potentially significant Arctic feedback loop, she explained.For now, all of this is still a question mark. More research is needed to understand how microplastics travel through the food web and what they do to the organisms that ingest them (Bergmann is hoping to conduct future studies specifically on the deep-sea creatures living among the plastic-inundated sediments). But if scientific experiments don’t soon reveal the consequences of our plastic dependence, time probably will. “As microplastic concentrations are increasing, we will see an increase in its effects. In certain areas or species, we may cross critical thresholds,” Bergmann said. “Some scientists think that we have already.”