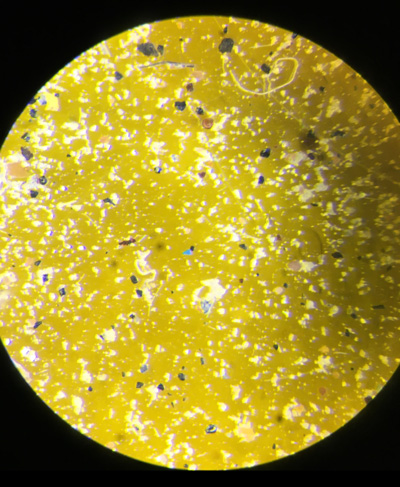

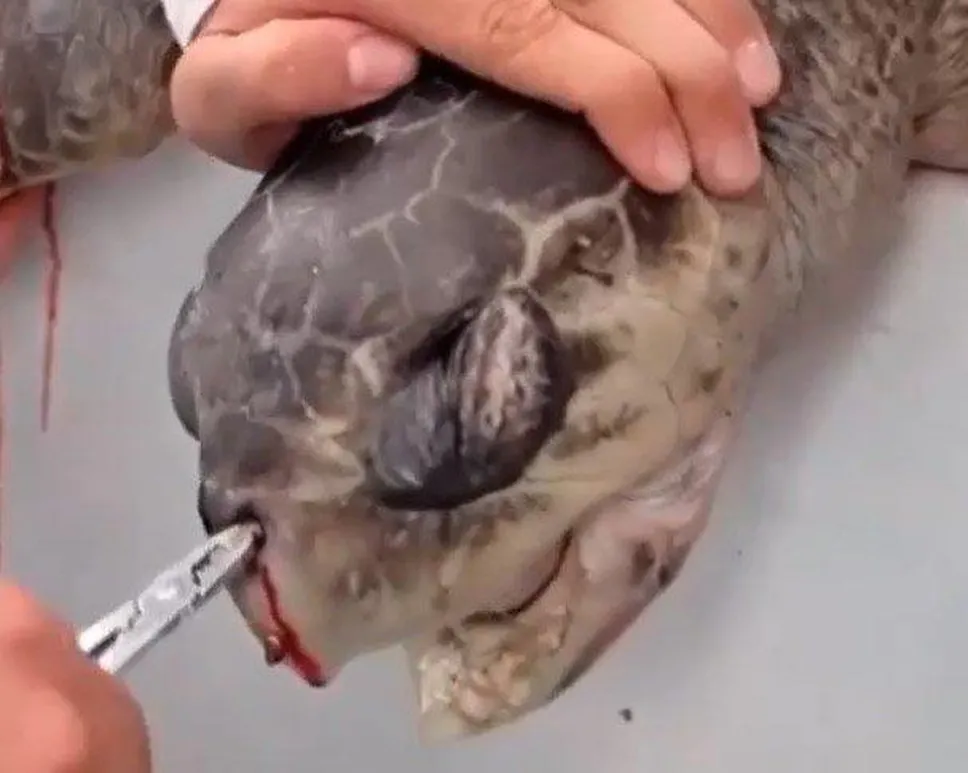

On the morning of the day I had decided to go without using plastic products — or even touching plastic — I opened my eyes and put my bare feet on the carpet. Which is made of nylon, a type of plastic. I was roughly 10 seconds into my experiment, and I had already committed a violation.Since its invention more than a century ago, plastic has crept into every aspect of our lives. It’s hard to go even a few minutes without touching this durable, lightweight, wildly versatile substance. Plastic has made possible thousands of modern conveniences, but it has come with downsides, especially for the environment. Last week, in a 24-hour experiment, I tried to live without it altogether in an effort to see what plastic stuff we can’t do without and what we may be able to give up.Most mornings I check my iPhone soon after waking up. On the appointed day, this was not possible, given that, in addition to aluminum, iron, lithium, gold and copper, each iPhone contains plastic. In preparation for the experiment, I had stashed my device in a closet. I quickly found that not having access to it left me feeling disoriented and bold, as if I were some sort of intrepid time traveler.I made my way toward the bathroom, only to stop myself before I went in.“Could you open the door for me?” I asked my wife, Julie. “The doorknob has a plastic coating.”She opened it for me, letting out a “this is going to be a long day” sigh.My morning hygiene routine needed a total revamp, which required detailed preparations in the days before my experiment. I could not use my regular toothpaste, toothbrush, shampoo or liquid soap, all of which were encased in plastic or made of plastic.Fortunately, there is a huge industry of plastic-free products targeted at eco-conscious consumers, and I had bought an array of them, a haul that included a bamboo toothbrush with bristles made of wild boar hair from Life Without Plastic. “The bristles are completely sterilized,” Jay Sinha, the company’s co-owner, assured me when I spoke with him the week before.Instead of toothpaste, I had a jar of gray charcoal-mint toothpaste pellets. I popped one in, chewed it, sipped water and brushed. It was nice and minty, though the ash-colored spit was unsettling.I liked my shampoo bar. A shampoo bar is just what it sounds like: a bar of shampoo. Mine was scented pink grapefruit and vanilla, and lathered up well. According to shampoo bar advocates, it is also cheaper than bottled shampoo on a per-wash basis (one bar can last 80 showers). Which is good, because the plastic-free life can be expensive. Package Free, a sleek outlet in the NoHo neighborhood of Manhattan that abuts Gwyneth Paltrow’s Goop store, sells a zinc and stainless-steel razor for $84 (as well as “the world’s first biodegradable vibrator”).An array of plastic-free items in the reporter’s bathroom.Jonah Rosenberg for The New York TimesA plastic-free morning shave, thanks to a razor made of zinc and steel.Jonah Rosenberg for The New York TimesA wool sweater knitted by hand completed the day’s outfit.Jonah Rosenberg for The New York TimesTaking a blogger’s advice, I mixed a D.I.Y. deodorant out of tea tree oil and baking soda. It left me smelling a little like a medieval cathedral, but in a good way. Making your own stuff is another way to avoid plastic, though it does require another luxury: free time.Before I was done in the bathroom, I had broken the rules a second time, by using the toilet.Getting dressed was also a challenge, given that so many clothing items include plastic. I had ordered a pair of wool pants that promised to be plastic free, but they had not arrived. In their stead, I chose a pair of old Banana Republic chinos.The tag said “100 percent cotton,” but when I had checked the day before with a very helpful Banana Republic public relations representative, it turned out to be a little more complicated. The main fabric is indeed 100 percent cotton, but there was plastic lurking in the zipper tape, the internal waistband, woven label, pocketing and threads, the representative told me. I cut my thumb trying to slice off the black brand label with an all-metal knife. Instead of a Band-Aid — yes, plastic — I used some gummed paper tape to stop the bleeding.Happily, my underwear did not represent a plastic violation — blue boxers from Cottonique made of 100 percent organic cotton with a cotton drawstring in place of the elastic (which is often plastic) waistband. I had found this item via an internet list of “14 Hot & Sustainable Underwear Brands for Men.”For my upper body, I lucked out. Our friend Kristen had knitted my wife a sweater for a birthday present. It had rectangles of blue and purple, and it was 100 percent merino wool.“Could I borrow Kristen’s sweater for the day?” I asked Julie.“You’re going to stretch it out,” Julie said.“It’s for planet Earth,” I reminded her.Plastics Present and PastThe world produces about 400 million metric tons of plastic waste each year, according to a United Nations report. About half is tossed out after a single use. The report noted that “we have become addicted to single-use plastic products — with severe environmental, social, economic and health consequences.”I’m one of the addicts. I did an audit, and I’d estimate that I toss about 800 plastic items in the garbage a year — takeout containers, pens, cups, Amazon packages with foam inside and more.Before my Day of No Plastic, I immersed myself in a number of no-plastic and zero-waste books, videos and podcasts. One of the books, “Life Without Plastic: The Practical Step-by-Step Guide to Avoiding Plastic to Keep Your Family and the Planet Healthy,” by Mr. Sinha and Chantal Plamondon, came from Amazon wrapped in clear plastic, like a slice of American cheese. When I mentioned this to Mr. Sinha, he promised to look into it.I also called Gabby Salazar, a social scientist who studies what motivates people to support environmental causes, and asked for her advice as I headed into my plastic-free day.“It might be better to start small,” Dr. Salazar said. “Start by creating a single habit — like always carrying a stainless-steel water bottle. After you’ve got that down, you start another habit, like taking produce bags to the grocery. You build up gradually. That’s how you make real change. Otherwise, you’ll just be overwhelmed.”“Maybe being overwhelmed will bring some sort of clarity?” I said.“That’d be nice,” Dr. Salazar said.Must avoid: All of these items, which are part of the reporter’s everyday life, contain plastic.Photographs by Jonah Rosenberg for The New York TimesAdmittedly, living completely without plastic is probably an absurd idea. Despite its faults, plastic is a crucial ingredient in medical equipment, smoke alarms and helmets. There’s truth to the plastics industry’s catchphrase from the 1990s: “Plastics make it possible.”In many cases it can help the environment: Plastic airplane parts are lighter than metal ones, which mean less fuel and lower CO2 emissions. Solar panels and wind turbines have plastic parts. That said, the world is overloaded with the stuff, especially the disposable forms. The Earth Policy Institute estimates that people go through one trillion single-use plastic bags each year.The crisis was a long time coming. There’s some debate over when plastic entered the world, but many date it to 1855, when a British metallurgist, Alexander Parkes, patented a thermoplastic material as a waterproof coating for fabrics. He called the substance “Parkesine.” Over the decades, labs across the world birthed other types, all with a similar chemistry: They are polymer chains, and most are made from petroleum or natural gas. Thanks to chemical additives, plastics vary wildly. They can be opaque or transparent, foamy or hard, stretchy or brittle. They are known by many names, including polyester and Styrofoam, and by shorthand like PVC and PET.Plastic manufacturing ramped up for World War II and was crucial to the war effort, providing nylon parachutes and Plexiglas aircraft windows. That was followed by a postwar boom, said Susan Freinkel, the author of “Plastic: A Toxic Love Story,” a book on the history and science of plastic. “Plastic went into things like Formica counters, refrigerator liners, car parts, clothing, shoes, just all sorts of stuff that was designed to be used for a while,” she said.Then things took a turn.“Where we really started to get into trouble is when it started going into single-use stuff,” Ms. Freinkel said. “I call it prefab litter.”The outpouring of straws, cups, bags and other ephemera has led to disastrous consequences for the environment. According to a study by the Pew Charitable Trusts, more than 11 million metric tons of plastic enter oceans each year, leaching into the water, disrupting the food chain and choking marine life.Close to one-fifth of plastic waste gets burned, releasing CO2 into the air, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, which also reports that only 9 percent of plastics are recycled. Some aren’t economical to recycle, and other types degrade in quality when they are.Plastic may also harm our health. Certain plastic additives — such as BPA and phthalates — may disrupt the endocrine system in humans, according to the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. Worrying effects may include behavioral problems and lower testosterone levels in boys and lower thyroid hormone levels and preterm births for women.“Solving this plastic problem can’t fall entirely on the shoulders of consumers,” Dr. Salazar told me. “We need to work on it on all fronts.”It’s EverywhereEarly in my no-plastic day, I started to see the world differently. Everything looked menacing, like it might be harboring hidden polymers. The kitchen was particularly fraught. Anything I could use for cooking was off-limits — the toaster, the oven, the microwave. Even leftovers were a no-go. My son waved a plastic baggie filled with French toast. “You want some of this?” Yes, I did.Instead, I decided to go foraging for raw food items.I left my building using the stairs, rather than the elevator with its plastic buttons, and walked to a health food store near our apartment on the Upper West Side of Manhattan.When I go shopping, I try to remember to take a cloth bag with me. This time, I had brought along seven bags of varying sizes, all of them cotton. I also had two glass containers.At the store, I filled up one of my cotton bags with apples and oranges. On close inspection, I noticed that the each rind had a sticker with a code. Another likely violation, but I ignored it.At the bulk bins, I scooped walnuts and oatmeal into my glass dishes using a (washed) steel ladle I had brought from home. The bins themselves were plastic, which I ignored, because I was hungry.Scooping walnuts into a glass container with a steel ladle brought from home.Jonah Rosenberg for The New York TimesIt is not easy to pay without using plastic. Even paper currency may have synthetic ingredients.Jonah Rosenberg for The New York TimesGlass container? Bamboo fork? Cotton towel? Wooden chair? Check, check, check, check.Jonah Rosenberg for The New York TimesI went to the cashier. At which point it was time to pay. Which was a problem. Credit cards were out. So was my iPhone’s Apple Pay. Paper money was another violation: Although U.S. paper currency is made mainly of cotton and linen, each bill likely contains synthetic fibers, and the higher denominations have a security thread made of plastic to prevent counterfeiting.To be safe, I had brought along a cotton sack full of coins. Yes, a big old sack heavy with quarters, dimes and pennies — about $60 worth that I had withdrawn from Citibank and my kids’ piggy banks.At the checkout counter, I started stacking quarters as quickly as I could between nervous glances at the customers behind me.“I’m really sorry this is taking so long,” I said.“That’s OK,” the cashier said. “I meditate every morning so I can deal with turmoil like this.”He added that he appreciated my commitment to the environment. It was the first positive feedback I’d received. I counted out $19.02 — exact change! — and went home to eat my breakfast: nuts and oranges on a metal cookie tray, which I balanced on my lap.A couple of hours later, in search of a plastic-free lunch, I walked to Lenwich, a sandwich and salad shop in my neighborhood. I arrived early in the afternoon, toting my rectangular glass dish and bamboo cutlery.“Can you make the salad in this glass container?” I asked, holding it up.“One minute please,” the man behind the counter said, tersely.He called over a manager, who said OK. Victory! But the manager then rejected my follow-up request to use my steel scooper.After lunch, I headed to Central Park, figuring that this was a spot in Manhattan where I could relax in a plastic-free environment. I took the subway there, which scored me more violations, since the trains themselves have plastic parts and you need a MetroCard or smartphone to get through the turnstiles.At least I didn’t sit in one of those plastic orange seats. I had brought my own: an unpainted, fold-up Nordic-style teak chair, hard and austere. It’s what I had been using at the apartment to avoid the plastic-tainted chairs and couches.Fellow riders took little notice of the man in the wooden chair.Jonah Rosenberg for The New York TimesI plopped my chair down near a pole in the middle of the car. One guy had a please-don’t-talk-to-me look in his eyes, but the other passengers were so buried in their phones that the sight of a man on a wooden chair didn’t faze them.Walking through Central Park, I spotted dental floss picks, a black plastic knife and a plastic bag.Back home, I recorded some of my impressions. I wrote on paper with an unpainted cedar pencil from a “Zero Waste Pencil tin set” (regular pencils contain plastic-filled yellow paint). After a while, I went to get a drink of water. Which brings up perhaps the most pervasive foe of all, one I haven’t even mentioned yet: microplastics. These tiny particles are everywhere — in the water we drink, the air we breathe, in the oceans. They come from, among other things, degraded plastic litter.Are they harmful to us? I talked with several scientists, and the general answer I got was: We don’t know yet. “I think we’ll have an improved understanding in the next few years,” said Todd Gouin, an environmental research consultant. But those who are extra-cautious can use products that promise to filter microplastics from water and air.I had bought a pitcher by LifeStraw that contains a membrane microfilter. Of course, the pitcher itself had plastic parts, so I couldn’t use it on the Big Day. Instead, the night before, I spent some time at the sink filtering water and filling up Mason jars. Our kitchen looked like it was ready for the apocalypse.The water tasted particularly pure, which I’m guessing was some sort of a placebo effect.I wrote for a while. Then I sat there in my wooden chair. Phone-less. Internet-less. Julie took some pity on me and offered to play a game of cards. I shook my head.“Plastic coating,” I said.At about 9 p.m., I took our dog for her nightly walk. I was using a 100 percent cotton leash I bought online. I had ditched the poop bags — even the sustainable ones I found were made with recycled or plant-based plastic. Instead, I carried a metal spatula. Thankfully, I didn’t have to use it.Using the stairs after shopping, to avoid the elevator, which has plastic parts.Jonah Rosenberg for The New York TimesThe first draft of this article was written with a plastic-free pencil by candlelight.Jonah Rosenberg for The New York TimesCouldn’t use the bed (plastic).Jonah Rosenberg for The New York TimesAt 10:30 p.m., exhausted, I lay down on my makeshift bed — cotton sheets on the wood floor, since my mattress and pillows are plasticky.I woke up the next morning glad to have survived my ordeal and be reunited with my phone — but also with a feeling of defeat.I had made 164 violations, by my count. As Dr. Salazar had predicted, I felt overwhelmed. And also uncertain. There was so much that remained unclear, even after I had been studying this topic for weeks. What plastic-free items really made a difference, and what is mere green-washing? Is it a good idea to use boar’s-hair toothbrushes, tea tree deodorant, microplastic-filtering devices and paper straws, or does the trouble of using those things make everyone so bonkers that they actually end up damaging the cause?I called Dr. Salazar for a pep talk.“You can drive yourself crazy,” she said. “But it’s not about perfection, it’s about progress. Believe it or not, individual behavior does matter. It adds up.“Remember,” she continued, “it’s not about plastic being the enemy. It’s about single-use as the enemy. It’s the culture of using something once and throwing it away.”I thought back to something that the author Susan Freinkel had told me: “I’m not an absolutist at all. If you came into my kitchen, you would be like, what the hell? You wrote this book and look at how you live!”Ms. Freinkel does make an effort, she said. She avoids single-use bags, cups and packaging, among other things. I pledge to try, too, even after my not wholly successful attempt at a one-day ban.I’ll start with small things, building up habits. I liked the shampoo bar. And I can take produce bags to the grocery. I might event pack my steel water bottle and bamboo cutlery for my trips to Lenwich. And from there, who knows?And I’ll proudly wear the “Keep the Sea Plastic Free” T-shirt that I bought online in the days leading up to the experiment. It’s just 10 percent polyester.