Inscribed in any chunk of Antarctic snow, Crispin Halsall will tell you, is a story about how humans have treated the planet. Over the years, each round of precipitation at the South Pole has brought down the atmospheric detritus of the day: pollen; volcanic ash; and of particular interest to Halsall, human pollution. Antarctic pollution can originate as far away as the northern hemisphere, with volatile chemicals floating in the wind to arrive at the South Pole in a matter of days. “Those layers of snow become an environmental record of contamination, going back decades,” says Halsall, who is a chemist at Lancaster University in the UK. The world’s icy landscapes also foretell our environmental future. As icebergs and glaciers melt, pollutants trapped inside are released back into seas, waterways, and the air. Melting ice can unleash harmful molecules that damage ecosystems, deplete the ozone layer, or mess with the weather. And due to rising global temperatures, more and more of the world’s frozen landscapes are thawing. In the Alps and the Himalayas, “we are seeing the rerelease of old contaminants that have been locked up in ice for many decades,” says Halsall. It’s vital to know what’s being emitted.But interpreting what’s trapped in Antarctic snow is more complicated than previously thought. Researchers have discovered that the frozen water at Earth’s poles—contrary to conventional wisdom—is a hotbed of chemical reactions. What’s trapped within may transform over time.For a long time, scientists assumed the opposite: that frozen pollutants remain inert. “Most of the time, if you freeze something or make something colder, it slows things down,” says chemist Amanda Grannas of Villanova University in the US. Molecules move slower in solid ice and snow compared to liquid water, which means they collide less, leading to fewer opportunities to participate in chemical reactions. It’s why freezing raw meat keeps it from spoiling. It’s also why the bodies of several woolly mammoths, some 30,000 years old, have emerged preserved from frozen ground as it thaws.But in laboratory experiments, scientists have found that many pollutants—illuminated using bright light simulating the sun—break down faster in ice than in liquid water. In 2020, a team at the University of California, Davis observed that guaiacol, a molecule found in woodsmoke and consequently in bacon and whiskey, broke down into smaller compounds faster in ice than in liquid water. In 2022, they saw that the same applied to dimethoxybenzene, another molecule produced in smoke. This February, Halsall and his colleagues found that pollutants in car exhaust fumes—known as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons—also degraded faster in ice than in water.Researchers attribute this flurry of chemical activity in ice to a phenomenon known as the “freeze concentration effect.” As water cools to form ice, its constituent molecules line up in hexagonal crystals. “The stuff dissolved in the water gets forced out of that ice crystal structure,” says Grannas. “To the naked eye, it looks like a frozen ice cube. But microscopically, there’s these little pockets of liquid where the other chemicals get concentrated. The reactants have been shoved into this tiny volume together, and that makes the chemistry go a lot faster.”Ultraviolet light, found in sunshine, then triggers that chemical breakdown in the concentrated pollutants. Without it, the compounds remain relatively inert, like the food in your freezer. But under UV illumination, “by and large, we see faster rates of decay in ice than we do in water,” says Halsall. These accelerated decay rates may play out more noticeably in ice at the poles, where “you can have 24 hours of sunlight at certain portions of the year,” says Grannas. “That drives a lot of chemistry.”Microplastics, fragments of plastic less than 5 millimeters long, also break down faster in ice than in water. Chemists at Central South University in China found that over 48 days, microplastic beads less than a thousandth of a millimeter in diameter deteriorated in ice to the extent they would over 33 years in the Yangtze River. “Microplastics take hundreds of years, if not thousands, to break down,” Chen Tian of Central South University in China told WIRED, in Chinese. “We didn’t have that long, so we studied just the first step of degradation. But we think that the entire degradation process should be faster in ice.”Plastic waste is the most common form of marine debris—around 10 million tons of plastic ends up in the ocean every year, much of which breaks down into microplastics—so ice at the poles may be churning through the stuff. This might be good news, as it could help scientists figure out methods to break microplastics down faster, Tian and her colleagues point out in their paper. But by breaking microplastic down into ever smaller pieces, ice may also be making it an ever more pervasive pollutant. The smaller plastic fragments get, the deeper into organisms they penetrate. Microscopic plastic particles have been found in the brains of fish, causing brain damage.For Halsall, whose research aims to track human activity in Antarctic ice, the degradation of pollutants makes life more difficult. He’s particularly interested in perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS. These “forever chemicals” persist in the environment and are found in nonstick pans, engine oils, and all sorts of consumer products. In 2017, Halsall’s collaborators cut into the Antarctic to extract a 10-meter-long cylinder of packed snow that had accumulated since 1958. Specimens like this reveal climate and human activity, much as tree rings do in more temperate latitudes. The deeper the snow sample, the further back in time you go.Many chemical companies pivoted away from using “longer-chain” PFAS around the year 2000. In the snow deposited that year and after, Halsall’s team found less of that pollutant and more of its replacement compounds, “shorter-chain” PFAS. “We can spot in that snow core when industry changed,” says Halsall. But to accurately understand what was being used when, Halsall also needs to consider how much pollutants have degraded, as this may help explain differences in the chemicals found at various depths. These ice-borne reactions have impacts for the rest of us too. As glaciers at the poles melt, the sunlight-processed pollutants are released into the environment. “You might think, ‘We’re degrading a pollutant. That’s a good thing,’” says Grannas. “In some cases it is. But we’ve found, for some pollutants, the products they turn into can actually be more toxic than the original.” For example, Grannas and her colleagues found that the chemical aldrin, historically used in pesticides, could transform more readily into the even more toxic chemical dieldrin in ice. (Farmers also widely used dieldrin in pesticides in the 20th century, and the use of both chemicals is banned in most countries.)On a more optimistic note, Grannas says that studying how ice degrades pollutants will help researchers evaluate new substances. “We’re introducing new chemicals into our agricultural systems, pharmaceutical products, and daily use—laundry detergents and fragrances and personal products,” says Grannas. “We want to understand up front what will happen if we use this on a massive scale and emit it into the environment.” Some of those pollutants will end up frozen in glaciers or at the poles, and tracking the evolution of chemicals in ice gives researchers a more accurate sense of their potential environmental impact. At Earth’s poles, the inside of an ice cube is a tumultuous place.

Category Archives: Plastic Pollution Articles & News

‘It would survive nuclear Armageddon’: should plastic grass be banned?

My lawn is a disaster. To be honest, it’s not really a lawn at all. Any green is mostly moss, the rest is mud. More no man’s land than bowling green. The reasons for this are: small London garden (I know I am lucky to have one); not a lot of sun (stolen by the neighbour’s overhanging apple tree); two footballing boys (even though, now banned for life, they have to go to the park). And possibly also inexpertise on the part of the groundsman, though he has tried – I’ve turfed, and seeded, aerated, watered, fed, scarified, sung to it. I’m about ready to give up.There is an obvious solution: artificial grass. Beautifully, uniformly verdant all year round, low maintenance, no mowing required, no mower required, no watering, no mud. I might even let the boys back on to it. Or not.I’m not alone in thinking of faking it. A survey last year by Aviva found that 10% of UK homeowners with outside space had replaced at least some of their garden’s natural lawn with artificial grass, and a further 29% plan to or would consider making the swap. During the pandemic, when everyone was thinking about the outdoors, searches for “artificial grass” jumped 185% from May 2019 to 2020, according to Google Trends.My own search finds dozens of firms offering artificial grass, seducing me with pictures of lawns that look like the green baize of snooker tables. And promises – no mud, no sweat, no tears. And no guilt either – here’s one that says it’s “better for the environment” – because you don’t have to water, mow or fertilise. Well, that’s a relief, though we’ll return to this later.I might miss the smell of summer: freshly cut grass. What, I don’t have to? I can brush in artificial grass cleaner with that very fragrance? Happy days. Soon I have a quote for supply and installation, 40 sq metres of a mid-range product: £2,900 plus VAT. Ouch. But you can just buy the stuff for as little as £7 a sq metre – how hard can it be to DIY?Artificial grass was invented by James M Faria and Robert T Wright at Monsanto and first installed on a recreation area of a school in Providence Rhode Island in 1964. It hit the headlines a couple of years later when it was laid in the Astrodome in Houston, Texas, and became known as AstroTurf.Artificial turf for sport, now produced under different brand names by other companies, has become increasingly controversial, most seriously after being potentially linked to the deaths of six professional baseball players in Philadelphia, who had the same rare form of cancer. It often uses rubber granules from recycled tyres, which can contain heavy metals, benzene and other carcinogens. Artificial grass for domestic use and landscaping, which began to be a thing in the 1990s, is normally made from polypropylene or nylon (polyamide) and doesn’t often contain rubber granules. The global artificial turf market (including sports use and domestic use) grew 8.4% in the past year to $4.87 bn (£3.95bn) and is expected to reach $6.83 bn (£5.6bn) in 2027. No wonder so many companies want to put plastic over your garden.Before I take the plunge, I ask Guardian readers to share their experiences of artificial lawns. Some are positive. Several, including Don in Fife and Wayne in Worcester, mention their dogs digging up the old grass. And Alex in Surrey’s greyhounds used to bring mud into the house. Not any more. As well as dogs, children come up. “It’s been wonderful, and the grandchildren love it,” says Charles in Berkshire. And when it comes to croquet, in-house knowledge of the small bumps and inconsistencies in the surface allows them “to win against all comers”. Home advantage – I like it.Phil in Weston-super-Mare did it for his son to play football on – just a little bit in the goalmouth, “so it didn’t become a mud bath”. It was the same for Genevieve in Kent: her kids turned the garden into a quagmire, so they put down fake grass. “It was the most successful thing – they just played football all the time. It was brilliant to have a party on too – people put their fags out on it and it was fine. I think it would survive nuclear Armageddon.”This was a while back, in the 00s, when her family were pioneers of artificial grass. They’ve moved house since then: “We wouldn’t get artificial grass now.” Not just because the kids have grown up. “Because of all the reasons we now know we shouldn’t have it.”‘I can’t stand plastic grass!” bellows the naturalist Iolo Williams, who presents the BBC’s Springwatch, speaking from his home in mid-Wales. “It is hugely damaging to the environment on several levels. First of all it takes away the natural habitat from a whole host of species, notably invertebrates like earthworms, valuable in their own right but also a valuable food source for all kinds of birds and mammals.”Last year’s WWF Living Planet Report found that globally, wildlife populations have plunged by 69% over the past 50 years, with the UK one of the most nature-depleted countries in Europe. This is not the time to be destroying natural habitats and breaking up food chains.“If you want to see blackbirds and song thrushes, you’ve got to have grass full of invertebrates,” says Williams. “People are lamenting the decline of a lot of these birds, but if you stick down plastic grass, what do you expect? You reap what you sow. I would love to see plastic grass banned once and for all. It makes me very angry. I absolutely detest it.”Lynne Marcus, co-chair of the Society of Garden Designers, also underlines the fact that artificial lawns are no-go zones for wildlife. “People may say butterflies or bees can land around it, on the strips of soil we have with a few plants, but it’s like if you put a motorway down the middle of a forest. The animals can’t get from one side to the other to procreate.”With support from the Royal Horticultural Society and the Landscape Institute, the society has launched a campaign on this issue. It wants people to say no to fake grass. The charge sheet is a long one: artificial lawns destroy natural habitats and soil; they contribute to carbon emissions during manufacture and transport, whereas real grass absorbs CO2; they overheat in the summer and contribute to urban heat islands; they cause flooding as they absorb less than 50% of the rain that falls on them; they pollute waterways, as over time the plastic breaks down into microplastics, which is washed into our drainage and discharged into rivers and the sea; they are neither biodegradable nor recyclable, and after their life cycle (typically up to about 15 years) they go into landfill where they will continue to pollute.In short, they are an environmental nightmare, green in colour only. “Every time you put one down, you’re saying: ‘I know we’re all worried about climate change, but guess what, I’m going to contribute to it,’” says Marcus, before adding that she doesn’t want to blame people. “It’s about public engagement with the issue, informing and educating.”She rejects any idea that they are maintenance-free, explaining that over time they accumulate a buildup of excrement and urine from birds, mice, foxes, cats and dogs, and have to be regularly cleaned and disinfected.“You can’t get a plastic bag, yet you can cover your garden in plastic,” says Marcus. “It seems to me there should be something illegal about that.” And she thinks that in years to come we’ll look back at it in the same way as we now look back at driving without seatbelts or smoking next to babies. “Oh my God, can you believe it, we used to lay plastic lawns!”The tide does seem to be turning. The Chelsea Flower show banned fake grass last year. Ed Horne of the RHS, which runs the event, said: “Fake grass is just not in line with our ethos and views on plastic. We recommend using real grass because of its environmental benefits, which include supporting wildlife, mitigating flooding and cooling the environment.” The housing secretary Michael Gove plans to prevent developers from laying fake grass in new housing schemes.The mood is reflected in some more of our reader responses. In Somerset, JP put down a plastic lawn because it was a tiny patch and grass wouldn’t grow. “Within months it started stinking of urine due to the dog toileting on it. About six months ago we’d had enough and I ripped it out. I regret the waste of plastic. We now have a sedum lawn, which loves poor soil and is fantastic for pollinators. I wish we’d done that all along.”In South Ayrshire, Dennis inherited a plastic lawn when they moved to their place. “It was filthy, and had faded to a light insipid green.” So they removed it, and the gravel underneath, imported topsoil and compost, and planted butterfly- and bee-friendly shrubs and flowers. “Our garden, lifeless before, is now full of life.”Barbara Samitier, a French garden designer working in London, thinks that the need for a perfect green lawn may be a peculiarly British thing. “You can’t imagine a garden without it. I think it belongs to the kind of imagery maybe from cricket, Wimbledon, this green and pleasant land. It’s what people in this country have been raised to see as nature.”There are alternatives that aren’t plastic, even if you have a small, north-facing city garden and children. “You can do a little woodland, make it more a sort of exploratory playground. A family garden doesn’t need to be about an expanse of lawn – there are different ways to engage children outdoors.”Even if you have a lawn, it doesn’t have to look like Centre Court on the opening day of Wimbledon. “If I look at a perfect lawn, it doesn’t make me feel relaxed,” says Samitier. “I’m thinking it uses a lot of water, requires a lot of cutting, also chemicals to keep it weed-free and to keep it going in spite of the changes in weather. Whereas if I look at a less perfect lawn with maybe some long grass, areas that haven’t been mown, I know there is a lot of life in there, insects and pollinators. For me, that looks a lot more beautiful.”It’s about accepting the seasons. “It doesn’t have to be perfect all the time, so in the winter it gets muddy, in the summer it’s dry but that’s fine: it comes back when it rains. I think in England a lot of gardens are about ego and controlling, making everything do exactly what you want, the grass needs to be perfect and all of this. But now we see the beauty of letting go a bit and accepting we don’t have to control everything.”Artificial grass makes Samitier’s heart sink. “Don’t do it! You’ll regret it,” she warns me.But it’s OK, because I’m already moving away from plasticking over my scruffy little urban patch and trying to see it in a new light. Not mud and mess, but life and beauty … well, let’s not carried away. Not no man’s land, though, nor no beast’s land. There is birdsong. And right on cue, almost as if it was paid, a dunnock shuffles on to my not-lawn and starts hopping around, hunting for breakfast.

West Coast MP wants Ottawa to ban plastic foam causing a wave of pollution

Light, buoyant and cheap, polystyrene foam is commonly used for docks, buoys, pontoons at marinas and other water activities throughout Canada. But the plastic, oil-based product is causing a wave of pollution in oceans and waters across the country, says B.C. NDP MP Rachel Blaney. The federal government needs to ban the use of expanded polystyrene (ESP) and extruded polystyrene (XP), commonly known as Styrofoam, in floating structures in both freshwater and saltwater, said Blaney, the MP for North Island-Powell River.Get daily news from Canada’s National ObserverPolystyrene foam never breaks down, but degrades into thousands of small puffed plastic fragments that travel long distances and are extremely hazardous to aquatic environments, she said. “It’s just so harmful to our beaches, fish in the ocean and to wildlife on the shores,” Blaney said, adding polystyrene foam is a top complaint from communities in her riding involved in coastal cleanups. “As it breaks into those smaller and smaller microbeads, it’s absolutely impossible to clean up,” she said. “It’s crazy to think in this country that we’re putting foam into the water purposefully — we shouldn’t be doing that.” What people are reading B.C. NDP MP Rachel Blaney has tabled a motion to ban polystyrene foams when building aquatic infrastructure to prevent a tide of plastic pollution. Photo submitted Blaney has tabled a motion to ban the use of polystyrene foams to build floating structures and phase out their use in existing ones and has partnered with ocean conservation groups, including Surfrider Canada, on a letter-writing campaign supporting the ban. The federal government included Styrofoam takeout containers when it launched the phaseout of six single-use plastic items in December, Blaney noted. Polystyrene foam is a #plastic blight on beaches and waterways and is harmful to birds, fish and other marine creatures, says #NDP MP Rachel Blaney, who’s tabled a motion for the federal government to ban its use in floating structures. “But there’s just so much more that they could do,” she said, adding it’s not just a coastal issue. “It’s everywhere. Communities across Canada that are inland are having their lakes, rivers and waterways being polluted.” After Blaney submitted a petition to Parliament in the summer calling for a ban, the federal government said it wasn’t looking at prohibiting polystyrene foam in marine ecosystems. However, Environment Minister Steven Guilbeault noted Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) had new regulations obliging shellfish growers to encase any foam floats in hard plastic shells.Blaney said while the government doesn’t see the need for further action, coastal communities do. “We see the need,” she said. “I see it all the time in my constituency on the beaches and in the water, so that doesn’t work for me.”Banning foam floats a ‘no-brainer’Even if community volunteers remove large chunks of polystyrene foam from beaches, the most destructive microplastic puffs remain. Photo by Quadra Island Beach Clean Dream TeamBanning the use of polystyrene foam in aquatic infrastructure is a quick and relatively easy way to make a positive impact on marine ecosystems, said Peter Ross, senior scientist and director of water pollution at the Raincoast Conservation Foundation.“It’s an easy fix, especially when there are alternative materials available. It should be a no-brainer,” Ross said. The degradation of foam, either over time or set loose by stormy weather, is a chronic source of pollution and causes harm to animals that feed along the shore or on the surface of the water, like birds, fish, turtles and even marine mammals feeding or coming up for air, he said. This can lead to starvation or blockages that can eventually kill an animal, he said. “These microplastics float, which is a little bit different than many other plastics,” he said. “When you’ve got these tiny white things floating around, many, many species are going to mistake them for food.” And if the plastic foam beads are “biofouled” — darkened and covered with algae, bacteria, plankton or other organic matter after being in the water for an extended period of time — it’s going to mimic food to an even greater degree, Ross added. “Then it really starts to resemble, and even taste, like natural food,” he said. “It really brings up the risk of surreptitious consumption by some poor creature that thinks it’s actually something nutritious.” Stopping the flow of plastics before they enter waterways and oceans is the most effective way to tackle the scope of the problem, Ross said, adding technology and cleanups can’t keep pace with the amount of pollution entering the ocean. Foam pollution demoralizing for cleanup volunteers Members of B.C.’s Clean Coast, Clean Waters beach cleanup in the Discovery Islands collect polystyrene foam for transport. Photo courtesy Spirit of the West AdventuresQuadra Island resident Nevil Hand, who organizes regular beach cleanups in his community, agreed. Large or small, cleaning up foam is especially difficult, said the retired firefighter who organizes the Quadra Island Beach Clean Dream Team. In November, community volunteers cleaned up the island’s beaches, and within a month, winter storms had erased any sign the teams had been there, he said. “This winter, it seemed like an entire marina exploded to the south of us,” he said. “We’ve got big pieces of dock flotation here this year in amounts we’ve never seen before.” Clean team volunteers, now holding a spring cleanup contest, have been stacking up foam debris at beach trailheads for pick up, Hand said, adding it’s unsettling to see how much there is. “Foam is so fragile. It’s disgusting the way it breaks up so easily along our shores,” he said. Some volunteers just found a 12-foot-long piece of foam that they hope will dry out in the coming weeks so they can remove it. “The problem is we can only really deal with the bigger pieces,” he said. “Even then, when we’re handling it, it’s breaking up in our hands and we’re making even more of a mess.” It’s demoralizing because the small pieces are the most destructive to the environment, he added. “That’s what the birds and the fish are going to ingest and [it] will harm our wildlife with stomach poisonings and who knows what.” The environmental costs are high because people and marine industries want to continue using cheap materials, Hand said. “We don’t want to see it used in the marine environment. It just doesn’t belong here.” Rochelle Baker / Local Journalism Initiative / Canada’s National Observer

What Is the Carbon Footprint of a Plastic Bag

Plastic bags are one of the major sources of pollution in the environment, not only because of their non-biodegradability, which causes them to remain in the environment as litter for centuries, but also because of their significant carbon footprint. This article will explain what a carbon footprint of plastic bags is, why we need to …

Continue reading “What Is the Carbon Footprint of a Plastic Bag”

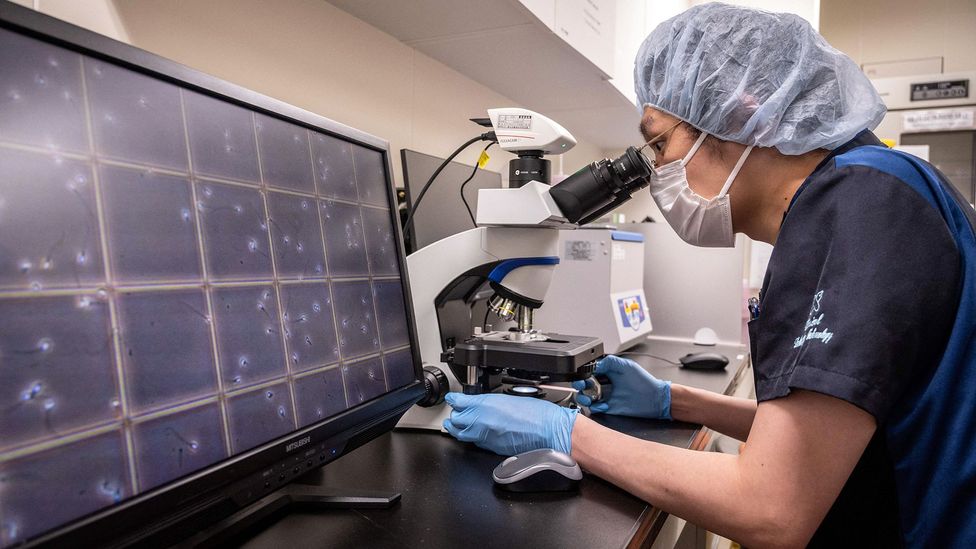

How pollution is causing a male fertility crisis

Sperm quality appears to be declining around the world but is a little discussed cause of infertility. Now scientists are narrowing in on what might be behind the problem.”We can sort you out. No problem. We can help you,” the doctor told Jennifer Hannington. Then he turned to her husband, Ciaran, and said: “But there’s not much we can do for you.”

The couple, who live in Yorkshire, England, had been trying for a baby for two years. They knew it could be difficult for them to conceive as Jennifer has polycystic ovarian syndrome, a condition that can affect fertility. What they had not expected was that there were problems on Ciaran’s side, too. Tests revealed issues including a low sperm count and low motility (movement) of sperm. Worse, these issues were thought to be harder to treat than Jennifer’s – perhaps even impossible.

Hannington still remembers his reaction: “Shock. Grief. I was in complete denial. I thought the doctors had got it wrong.” He had always known he wanted to be a dad. “I felt like I’d let my wife down.”

Over the years, his mental health deteriorated. He began to spend more time alone, staying in bed and turning to alcohol for comfort. Then the panic attacks set in.

“I hit crisis point,” he says. “It was a deep, dark place.”

Male infertility contributes to approximately half of all cases of infertility and affects 7% of the male population. However, it is much less discussed than female infertility, partly due to the social and cultural taboos surrounding it. For the majority of men with fertility problems, the cause remains unexplained – and stigma means many are suffering in silence.

Research suggests the problem may be growing. Factors including pollution have been shown to affect men’s fertility, and specifically, sperm quality – with potentially huge consequences for individuals, and entire societies.

A hidden fertility crisis?

The global population has risen dramatically over the past century. Just 70 years ago – within a human lifetime – there were only 2.5 billion people on Earth. In 2022, the global population hit eight billion. However, the rate of population growth has slowed, mainly due to social and economic factors.

Birth rates worldwide are hitting record low levels. Over 50% of the world’s population live in countries with a fertility rate below two children per woman – resulting in populations that without migration will gradually contract. The reasons for this decline in birth rates include positive developments, such as women’s greater financial independence and control over their reproductive health. On the other hand, in countries with low fertility rates, many couples would like to have more children than they do, research shows, but they may hold off due to social and economic reasons, such as a lack of support for families.There is mounting evidence that pollution may be at least partly behind declining sperm quality and sperm counts (Credit: Yuichi Yamazaki/AFP/Getty Images)At the same time, there may also be a decline in a different kind of fertility, known as fecundity – meaning, a person’s physical ability to produce offspring. In particular, research suggests that the whole spectrum of reproductive problems in men is increasing, including declining sperm counts, decreasing testosterone levels, and increasing rates of erectile dysfunction and testicular cancer.

Swimming cells

“Sperm are exquisite cells,” says Sarah Martins Da Silva, a clinical reader in reproductive medicine at the University of Dundee and a practicing gynaecologist. “They are tiny, they swim, they can survive outside the body. No other cells can do that. They are extraordinarily specialised.”

Seemingly small changes can have a powerful effect on these highly specialised cells, and especially, their ability to fertilise an egg. The crucial aspects for fertility are their ability to move efficiently (motility), their shape and size (morphology), and how many there are in a given quantity of semen (known as sperm count). They are the aspects that are examined when a man goes for a fertility check.

“In general, when you get below 40 million sperm per millilitre of semen, you start to see fertility problems,” says Hagai Levine, professor of epidemiology at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Sperm count, explains Levine, is closely linked to fertility chances. While a higher sperm count does not necessarily mean a higher probability of conception, below the 40 million/ml threshold the probability of conception drops off rapidly.

In 2022, Levine and his collaborators published a review of global trends in sperm count. It showed that sperm counts fell on average by 1.2% per year between 1973 to 2018, from 104 to 49 million/ml. From the year 2000, this rate of decline accelerated to more than 2.6% per year.Levine argues this acceleration could be down to epigenetic changes, meaning, alterations to the way genes work, caused by environmental or lifestyle factors. A separate review also suggests epigenetics may play a part in changes in sperm, and male infertility.

“There are signs that it could be cumulative across generations,” he says.

The idea that epigenetic changes can be inherited across generations has not been without controversy, but there is evidence suggesting it may be possible.

“This [declining sperm count] is a marker of poor health of men, maybe even of mankind,” says Levine. “We are facing a public health crisis – and we don’t know if it’s reversible.”

Research suggests that male infertility may predict future health problems, though the exact link is not fully understood. One possibility is that certain lifestyle factors could contribute to both infertility, and other health problems.

“While the experience of wanting a child and not being able to get pregnant is extraordinarily devastating, this is a much bigger problem,” says Da Silva.

Individual lifestyle changes may not be enough to halt the decline in sperm quality. Mounting evidence suggests there is a wider, environmental threat: toxic pollutants.

A toxic world

Rebecca Blanchard, a veterinary teaching associate and researcher at the University of Nottingham, UK, is investigating the effect of environmental chemicals found within the home on male reproductive health. She is using dogs as a sentinel model – a kind of early-warning alarm system for human health.

“The dog shares our environment,” she says. “It lives in the same household and is exposed to the same chemical contaminants as us. If we look at the dog, we could see what’s going on in the human.”

Her research concentrated on chemicals found in plastics, fire retardants and common household items. Some of these chemicals have been banned, but still linger in the environment or older items (read more about this in BBC Future’s story on “forever chemicals”). Her studies have revealed that these chemicals can disrupt our hormonal systems, and harm the fertility of both dogs and men.

“We found a reduction in sperm motility in both the human and the dog,” says Blanchard. “There was also an increase in the amount of DNA fragmentation.”IVF treatment is offering hope to couples with fertility problems, but it is expensive and not available to everyone (Credit: Alamy)Sperm DNA fragmentation refers to damage or breaks in the genetic material of the sperm. This can have an impact beyond conception: as levels of DNA fragmentation increase, explains Blanchard, so do instances of early-term miscarriages.

The findings chime with other research showing the damage to fertility caused by chemicals found in plastics, household medications, in the food chain and in the air. It affects men as well as women and even babies. Black carbon, forever chemicals and phthalates have all been found to reach babies in utero.Support for men with fertility problemsAt his lowest point, Ciaran Hannington found HIMfertility, a male-only online group supporting men with fertility struggles by offering a space for them to share their thoughts and concerns. He now coaches others preparing for fertility treatment: “No one should feel like they’re on their own.”Climate change may also negatively impact male fertility, with several animal studies suggesting that sperm are especially vulnerable to the effects of increasing temperatures. Heatwaves have been shown to damage sperm in insects, and a similar impact has been observed in humans. A 2022 study found that high ambient temperature – due to global warming, or working in a hot environment – negatively affects sperm quality.

Poor diet, stress and alcohol

Alongside these environmental factors, individual problems can also harm male fertility, such as a poor diet, sedentary lifestyles, stress, and alcohol and drug use.

In recent decades there has been a shift towards people becoming parents later in life – and while women are often reminded about their biological clock, age was thought not to be an issue for male fertility. Now, that idea is changing. An advanced paternal age has been associated with lower sperm quality and reduced fertility.

There is a growing call for greater understanding of male infertility and new approaches for its prevention, diagnosis and treatment – as well as an increased awareness of the urgent need to tackle pollution. Meanwhile, is there anything an individual can do to protect or boost their sperm quality?

Exercise and a healthier diet may be a good start, since they have been linked to improved sperm quality. Blanchard recommends choosing organic food and plastic products free of BPA (Bisphenol A), a chemical associated with male and female fertility problems. “There are small things that you can do,” she says.

And, says Hannington, don’t suffer in silence.

After five years of treatment and three rounds of ICSI (Intracytoplasmic Sperm Injection), an IVF technique in which a single sperm is injected into the centre of an egg, he and his wife had two children. For people who have to pay for fertility treatments themselves, such a procedure may however not be affordable. In the US, a single round of IVF can cost upwards of $30,000 (£24,442) and insurance coverage for IVF can depend on the state you live in and who your employer is. And Hannington says he still feels the mental toll of his ordeal.

“I’m grateful for my children every day, but you just don’t forget,” he says. “It will always be part of me.”

—

Join one million Future fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter or Instagram.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “The Essential List” – a handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife, Travel and Reel delivered to your inbox every Friday.

Plastics are devastating the guts of seabirds

Northern fulmars and Cory’s shearwaters are masters of the sea and air, gliding above the waves and plunging into the water to snag fish, squid, and crustaceans. But because humans have so thoroughly corrupted the ocean with microplastics—at least 11 billion pounds of particles float at the surface, and that’s likely a huge underestimate—their diet now also includes substantial amounts of synthetic poison. A study published today in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution shows that those microplastics (defined as particles under 5 millimeters long) might be altering the seabirds’ gut microbiomes, with as-yet-unknown implications for their health. Another recent paper introduced the world to “plasticosis”: severe scarring in the digestive system of birds that had eaten plastic. With plastic pollution increasing exponentially along with plastic production, the new papers are a hint of the suffering to come.The researchers behind today’s paper dissected 85 northern fulmars and Cory’s shearwaters caught in the wild. (Northern fulmars live around northern oceans and the Arctic; Cory’s shearwaters throughout the Atlantic.) Then the team flushed plastic particles out of the birds’ digestive tracts, looking for bits as small as 1 millimeter, and analyzed the species of microbes in the gut. When the researchers analyzed microplastics in the birds by mass, the greater the mass, the lower the gut microbiome diversity. But when they counted the number of plastic particles, “the more particles there were, the more diverse the microbiome was,” says Gloria Fackelmann, a microbiome biologist at Ulm University in Germany, and lead author of the study. In this case, diversity isn’t necessarily a good thing: The more particles, the more pathogenic and antibiotic-resistant microbes the researchers found in the gut. In other words, a shift in the microbiome appears to favor potentially harmful, pathogenic microbes. Significantly, it happened among seabirds that had been eating “environmentally relevant” amounts of microplastics—meaning, what they found in their own habitat. (In previous laboratory studies, scientists have exposed various species to unrealistically high concentrations of microplastic.)This paper didn’t track whether the birds became sickened by microbial diseases, “so we can’t say the seabirds that had more plastic were unhealthier,” says Fackelmann. But that will be one of the big questions as researchers try to parse what effects the particles might be having. As microplastics break down, they leach out their component chemicals—around 10,000 varieties are used in plastics, many of which are known to be toxic to life. They’re especially prone to leach in a hot, acidic place like a digestive tract. “This all paints a really scary picture,” says Britta Baechler, associate director of ocean plastics research at the Ocean Conservancy, who wasn’t involved in either of the new papers. The gut, she says, is “a very harsh environment—things can be released, and that includes pathogens, bacteria, but also chemical contaminants.” As microplastics tumble through the ocean, they accumulate an extremely diverse community of viruses, algae, and even the tiny larvae of animals. (An especially common bacteria that scientists are finding on microplastics is Vibrio, which causes severe illness when people eat raw or undercooked seafood or are exposed to hurricane floodwaters.) This teeming world even has its own name: the plastisphere. When a fish or bird accidentally eats microplastic, it also eats that community of lifeforms. “If a seabird is ingesting more of these particles, and it does act as a vector, then you would have a higher diversity” of gut microbes, says Fackelmann.This might be why her team got contrasting results in their analysis: The more individual microplastics in the gut, the greater the microbial diversity, but the higher mass of microplastics, the lower the diversity. The more particles a bird eats, the greater the chance that those hitchhiking microbes take hold in its gut. But if the bird has just eaten a higher mass of microplastics—fewer, but heavier pieces—it may have consumed fewer microbes from the outside world.Meanwhile, particularly jagged microplastics might be scraping up the birds’ digestive systems, causing trauma that affects the microbiome. Indeed, the authors of the plasticosis paper found extensive trauma in the guts of wild flesh-footed shearwaters, birds that live along the coasts of Australia and New Zealand, that had eaten microplastics and macroplastics. (They also looked at plastic particles as small as 1 millimeter.) “When you ingest plastics, even small amounts of plastics, it alters the structure of the stomach, often very, very significantly,” says study coauthor Jennifer Lavers, a pollution ecologist at Adrift Lab, which researches the effects of plastic on sea life.Specifically, they found catastrophic damage to the birds’ tubular glands, which produce mucus to provide a protective barrier for the inside of the stomach, as well as hydrochloric acid, which digests food. Without these key secretions, Lavers says, birds “also can’t digest and absorb proteins and other nutrients that keep you healthy and fit. So you’re really prone and susceptible to exposure to other bacteria, viruses, and pathogens.”Scientists call this a “sublethal effect.” Even if the ingested pieces of plastic don’t immediately kill a bird, they can severely harm it. Lavers refers to it as the “one-two punch of plastics” because eating the material harms the birds outright, then potentially makes them more vulnerable to the pathogens they carry.A major caveat to today’s paper—and the vast majority of microplastics research—is that most scientists haven’t been analyzing the smallest of plastic particles. But researchers using special equipment have recently been able to detect and quantify nanoplastics, on the scale of millionths of a meter. These are much, much more numerous in the environment. (This is also why the finding that there are 11 billion pounds of plastic floating on the ocean’s surface was probably a major underestimate, as that team was only considering particles down to a third of a millimeter.) But the process of observing nanoplastics remains difficult and expensive, so Fackelmann’s group can’t say how many might have been in the seabirds’ digestive systems, and how they too might influence the microbiome. It’s not likely to be good news. Nanoplastics are so small that they can penetrate and harm individual cells. Experiments on fish show that if you feed them nanoplastics, the particles end up in their brains, causing damage. Other animal studies have also found that nanoplastics can pass through the gut barrier and migrate to other organs. Indeed, another paper Lavers published in January found even microplastics in the flesh-footed shearwaters’ kidneys and spleens, where they had caused significant damage. “The harm that we demonstrated in the plasticosis paper is likely conservative because we didn’t deal with particles in the nanoplastic spectrum,” says Lavers. “I personally think that’s quite terrifying because the harm in the plasticosis paper is quite overwhelming.”Now scientists are racing to figure out whether ingested plastics can endanger not only individual animals, but whole populations. “Is this harm at the individual level—all of these different sublethal effects, exposure to chemicals, exposure to microbiome changes, plasticosis—is it sufficient to drive population decline?” asks Lavers. The jury is still out on that, as scientists don’t have enough evidence to form a consensus. But Lavers believes in the precautionary principle. “A lot of the evidence that we have now is deeply concerning,” she says. “I think we need to let logic prevail and make a fairly safe, conservative assumption that plastics are currently driving population decline in some species.”

Want to help rid the ocean of plastic? Grab an oar

“We are fishing for marine plastic under sail,” says Steve Green, of Clean Ocean Sailing (COS). From their roving, rabble-rousing home and headquarters on the Annette, a 115-year-old sailing boat, Green and his co-captain, Monika Hertlová, are leading a naval attack on the plastic polluting our oceans — which weighs in at an estimated total between 75 million and 199 million tons.

Based on the coast of Cornwall in the UK, COS launched in 2017 after Green visited an island in the nearby Isles of Scilly archipelago. He was shocked at the amount of plastic pollution he saw.

“It’s only a mile across, and on the southwest of the island it is six foot deep of all sorts of plastic flotsam and jetsam. It’s full of dead or dying seabirds and dolphins,” says Green, who is “pirate-in-chief” at COS. He decided to do something about the problem and invited other concerned locals to join him in the mission to remove plastic waste from the most inaccessible parts of Cornwall’s commanding coastline. Since then, over 400 volunteers have leapt aboard to join the fixed crew of Green, Hertlová, four-year-old Simon and Labrador Rosie to sail under the Jolly Roger that flies at “Annie’s” prow.

The 60-ton former Dutch icebreaker acts as a mobile basecamp, sailing the high seas before pulling into rocky coves and river mouths so that a flotilla of smaller kayaks and rowing boats can disembark. The smaller vessels are able to reach shorelines that are difficult to access by land and that are some of the areas worst affected by plastic pollution. Plus, by using non-motorized vessels, they avoid burning carbon-emitting fossil fuels.

The group has recorded and removed 500,000 individual pieces of plastic with a combined weight of over 70 tons. Green says that about 85 percent of the rubbish they gather is recycled and repurposed. The Ocean Recovery Project in Exeter upcycles some into sea kayaks that COS then uses to remove more rubbish from nature.

COS volunteers Simon and Aude

Many Clean Ocean Sailing volunteers have a deep connection to the land and seas of Cornwall. Simon Myers grew up locally before moving away for work. During a particularly stormy winter, he returned to join the crew with his 16-year-old son Milo. For him and many of the volunteers, the work is a way to combat global issues on a local scale. “Living in western Europe we have been largely insulated from pretty much all of the consequences of our actions over the last 50 or 60 years, but we have an emotional attachment to this landscape, coastline and people. These issues around overconsumption, pollution and climate change are becoming increasingly personal. We love this part of the world. We grew up here and want to protect it,” says Myers.

Steve Green

The group is prepared to brave all weather and rough seas. They try to stay close to home when the weather demands it, but in favorable conditions they travel far up and down the coast and to the many small islands off Cornwall.

Green picks up plastic from a river bank.

Green, a native Cornishman, knows the local waterways like the back of his hand. He knows which coves, inlets, beaches and banks are susceptible to excessive plastic pollution.

Sailing ship Annette at night

Green believes COS’s method of ocean cleanup could be replicated in many of the world’s coastal areas. “There are a lot of traditional wooden boats and still a lot of people with the skills to maintain them,” he says. “I think it’s important to maintain that heritage. So long as you’re not in a hurry it is also an incredibly efficient way to move extremely heavy loads. Once the boat’s started moving, it just glides along not using any energy at all other than the natural forces of the wind and the tide.”

Ghost gear washed ashore

COS also has a “rapid response unit.” “People send us a picture or location and we have about 20 volunteers who are all set up and ready to go to pick up any ‘ghost gear’ before it gets washed out to sea again on the next tide. We have found fish crates and fishing gear from South Africa, China, South and North America. It’s crazy,” says Green.

COS volunteers clean up a beach.

A system of mutual support built on local friendships is the backbone of COS’s success. Many locals who can’t donate time offer the group goods such as beers, groceries and pasties to help keep the boat afloat and the team energized.

Rowing to hard to access spots

Annie’s “pirates” are committed to low-carbon plastic pollution cleanup. “We could go out there in big, engine-powered RIBS; we could modify tractors and all sorts to haul vast quantities of rubbish off the coast,” Green says. “But then, we would be creating another problem whilst trying to solve this one. This is nature and people working together in harmony.”

He adds, “By moving the big boat around on the sail and using oars and paddles to move the little boats around, not only are we not disturbing the wildlife but we’re not harming the natural environment at all. It takes a long time and it’s a lot of hard work, but we’re not creating a carbon footprint.”

Volunteers Simon and Milo heaving plastic

Sailing and paddling also holds an allure for volunteers, in addition to minimizing the environmental impact of COS’s work. “We are standing next to a Jolly Roger, at the mercy of the wind; it’s romantic, it’s under sail. There is a need to have quite visible, demonstrable ways to counterbalance a consumer culture,” says Myers.

The Annette flies the Jolly Roger.

“It’s also about other people seeing us doing this. Perhaps they’ll start to think about not dropping it in the first place or, even better, not buying it. That’s what’s really going to change the world,” says Green.

The Annette is a 60-ton former Dutch icebreaker.

The going can be tough for the crew, with long days of hard physical work followed by yet more days of careful sorting before sailing up the coast to the recycling center. Despite new waves of pollution washing up ashore with every fresh tide, they are determined to keep fighting back. “It’s great to see a growing amount of people with an attitude of seeing this wonderful planet as our collective home that we’re all responsible for,” says Green. As they continue to recruit new pirates for pollution-busting adventures, their message couldn’t be clearer: “All aboard.”

Why bioplastics won't solve our plastic problems

Last month, Victoria banned plastic straws, crockery and polystyrene containers, following similar bans in South Australia, Western Australia, New South Wales and the ACT. All states and territories in Australia have now banned lightweight single-use plastic bags.

You might wonder why we have to ban these products entirely. Couldn’t we just make them out of bioplastics – plastics usually made of plants? Some studies estimate we could swap up to 85% of fossil-fuel based plastics for bioplastics.

Unfortunately, bioplastics aren’t ready for prime time – except for their use in kitchen caddy bins as food waste liners. In Australia, we don’t have widely available pathways to compost or process them at the end of their lives. Nearly always, they end up in landfill.

That’s why many states are including bioplastics in their plastics bans. Avoiding single-use plastics entirely, whether traditional fossil fuel-based plastics or bioplastics, is more sustainable. And as our recycling system struggles, less plastic of any kind is simply better.

Bioplastics come from plants such as corn – and that comes with environmental impacts.

Shutterstock

Bio-based, biodegradable and compostable are different

Bioplastics is a blanket term covering plastics which are biologically-based or biodegradable (including compostable), or both.

Plastics are materials based on polymers – long-repeating chains of large molecules. These molecules don’t have to be oil-based – biologically-based plastics are made from raw materials such as corn, sugarcane, cellulose and algae.

Biodegradable plastics are those plastics able to be broken down by microorganisms into elements found in nature. Importantly, biodegradable here doesn’t specify how long or under what conditions plastic will break down.

Compostable plastics biodegrade on a known timeframe, when composted. In Australia, they can be certified for commercial or home compostable use.

These differences are important. Many of us would see the word “bioplastic” and assume what we’re buying is plant based and breaks down quickly. That’s often not true. Some biodegradable plastics are even made from fossil fuels.

Compostable bin caddies are the main sustainable use for bioplastics at present.

Shutterstock

Are bioplastics broadly more environmentally friendly?

To understand this we need to look at the whole lifecycle of the plastic, how it is made, used and what happens to it at end-of-life. Manufacturing bio-based plastics generally has lower environmental impacts and has less greenhouse gas emissions than fossil fuel plastics.

This isn’t always the case. Producing plastics from plants has an environmental impact from the use of land, water and agricultural chemicals. Increased demand for agricultural land could lead to biodiversity loss and can compete with food production.

Read more:

If plastic comes from oil and gas, which come originally from plants, why isn’t it biodegradable?

Bioplastics often sub in for familiar single use items such as plastic bags, takeaway coffee cups and cutlery. Around 90% of the bioplastics sold in Australia are certified compostable. In most of these applications a reusable alternative would be the most sustainable option.

Some applications have beneficial environmental outcomes: compostable bags for kitchen food waste caddies increase the rate of food waste collected, which means less food waste in landfill and fewer greenhouse gas emissions.

What about the crucial question of plastic waste and pollution? Sadly, if bioplastics end up in the environment, they can damage the environment in the same way as conventional plastics, such as contaminating soil and water. A turtle can choke just as easily on a bioplastic bag as a conventional plastic bag. That’s because biodegradable plastics still take years or even decades to biodegrade in nature.

Ideally, bioplastics should be designed to be either recyclable or compostable. Unfortunately, some bioplastics are neither. These pose problems for our waste management system, as they often end up contaminating recycling or compost bins when the only place for them is the tip.

In recent research for WWF Australia, we found widespread greenwashing in the industry, with terms such as “earth friendly” and “plastic-free” adding to the confusion. Regulating the industry and standardising terms would make it easier for us all to choose.

Compostable plastics almost all end up in landfill

Compostable plastics are designed to be broken down in the compost. Some can be composted at home, but others have to be done commercially.

The problem is these plastics aren’t being composted most of the time. Australian Standard compostable plastics are accepted in food organics and garden organics bins in South Australia and some councils in Hobart. But everywhere else, access to these services is limited. Many councils in other states will accept food and green waste – but specifically exclude compostable plastics (some accept council-supplied food waste caddy liners).

Read more:

Do you toss biodegradable plastic in the compost bin? Here’s why it might not break down

This means most compostable plastics used in Australia end up in landfill, where they emit methane as they break down, where it is not always captured. There’s no benefit using bioplastics if they can’t – or won’t – be recycled or composted, especially if they’re replacing a plastic that’s readily recyclable, such as the PET used in soft drink bottles.

Bioplastics still take time to degrade in landfill- and emit methane as they do so.

Shutterstock

Where does it make sense to use bioplastics in Australia?

When you reach for a bioplastic product, you’re probably doing it to reduce plastic waste. Unfortunately, we’re not there yet. We need viable pathways for recycling and composting.

So should we avoid them altogether? If you use compostable bin caddies and compost them at home or your council accepts them, that’s a useful option. But for most other uses, it’s far better to just not use plastic at all. Your reusable coffee cup and shopping bags are the best option.

Read more:

When biodegradable plastic is not biodegradable

Echo sounder buoys surprise beachcombers, anger reef guardians as more drift to Great Barrier Reef

An alarming number of strange-looking devices are washing up on Australian shores and the Great Barrier Reef, confounding beachcombers and worrying conservationists.Key points:The echo sounder buoys are used to detect fish in the South PacificQueensland commercial fishing fleets are finding them on the Great Barrier ReefConservationists are repurposing the buoys to target marine debrisThe floating echo sounders, which look like a cross between a landmine and a robot vacuum, are used by some foreign fisheries to detect and attract fish.The buoys, and the nets often attached to them, are becoming a common sight in Australian waters.This week, one of the mysterious-looking buoys washed up on a Queensland beach at Wunjunga in the Burdekin Shire south of Townsville.Reef advocates say they’re sitting on backyard stockpiles of the devices, which have been handed in.The echo sounder buoys have become a weekly discovery for commercial reef line fisherman Chris Bolton, who operates between Cairns and Townsville.”We’re finding them very regularly now, at least once a week,” Mr Bolton said.”I’m not sure how so many are getting lost.”I would say 90 per cent of the ones we find are caught on the reef.”It’s certainly a concern. It’s pollution.”Marine debris watchdog Tangaroa Blue Foundation said the buoys come from the South Pacific where fisheries, especially the long line industry, use them to detect fish.Dozens of the buoys have been donated to the not-for-profit, which is dedicated to the removal and prevention of marine debris.Lost at seaThe foundation’s chief executive Heidi Tate said some have been found as far south as New South Wales.”We do find them washing up in northern Australia every year because of the current from the South Pacific Ocean that comes towards the north,” she said.”A couple of weeks ago someone sent me a photo of one on a Sydney beach.””There are some estimates from the South Pacific fishing fleet area that somewhere between 45 to 65,000 of these beacons can be used annually.”They’ve just been lost.”

Fish sculpture aims to cut plastic pollution

South Tyneside CouncilA new seafront sculpture on Tyneside is aiming to cut the amount of plastic waste left by beachgoers.Named Feed the Fish, the artwork at Sandhaven, South Shields, is designed so people can dispose of plastic bottles which are then recycled.South Tyneside Council said it hoped it would encourage visitors to keep plastic off the beach and reduce the amount washed into the sea.The authority will work with schools and local groups to name the fish.Councillor Joan Atkinson, deputy leader of the council, said the landmark would “help to raise awareness of the risk” plastic poses to the environment.”The danger of plastic pollution to marine life and birds is well-documented.”We hope that this new sculpture will inspire and engage beach visitors to support our efforts to keep plastic off the beach and prevent it being washed into the ocean.”Every piece of plastic that is fed to the fish will make a difference to our planet through preventing pollution and supporting recycling.”It comes after the council installed 25 additional recycling bins along the seafront area last summer.Follow BBC North East & Cumbria on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram. Send your story ideas to northeastandcumbria@bbc.co.uk.Related TopicsPlasticPlastic pollutionSouth ShieldsSouth Tyneside CouncilEnvironmentRelated Internet LinksSouth Tyneside CouncilThe BBC is not responsible for the content of external sites.