One of the most heralded advanced plastic recycling companies in the United States, PureCycle Technologies, has signaled that it could be in some serious financial trouble.

Late last week, PureCycle told regulators at the U.S. Security and Exchange Commission that it would miss its deadline for filing a 2022 annual report. In two SEC filings, the eight-year-old company revealed a potential default on $250 million in revenue bonds issued by a local development agency to finance construction of the company’s first flagship recycling plant, in Ohio.

PureCycle’s loan agreement with investors promised a Dec. 1 completion date for the plant, which the company says is almost finished, along the Ohio River in Ironton, 130 miles southeast of Cincinnati. The company reported that it was negotiating with bondholders on whether the delay means that a default will be declared on the bonds, and if so, whether the parties can reach an agreement on a revised timetable and other matters.

Since it rolled out its technology, developed by the Cincinnati-based consumer goods company Procter & Gamble, in 2017, PureCycle has cast itself as a pathbreaker in recycling polypropylene, a highly versatile and durable plastic found in everything from drink cups and yogurt tubs to car dashboards, coffee pods and clothing fibers. In addition to the Ironton plant, the company is constructing another recycling facility in Georgia and has announced one for South Korea.

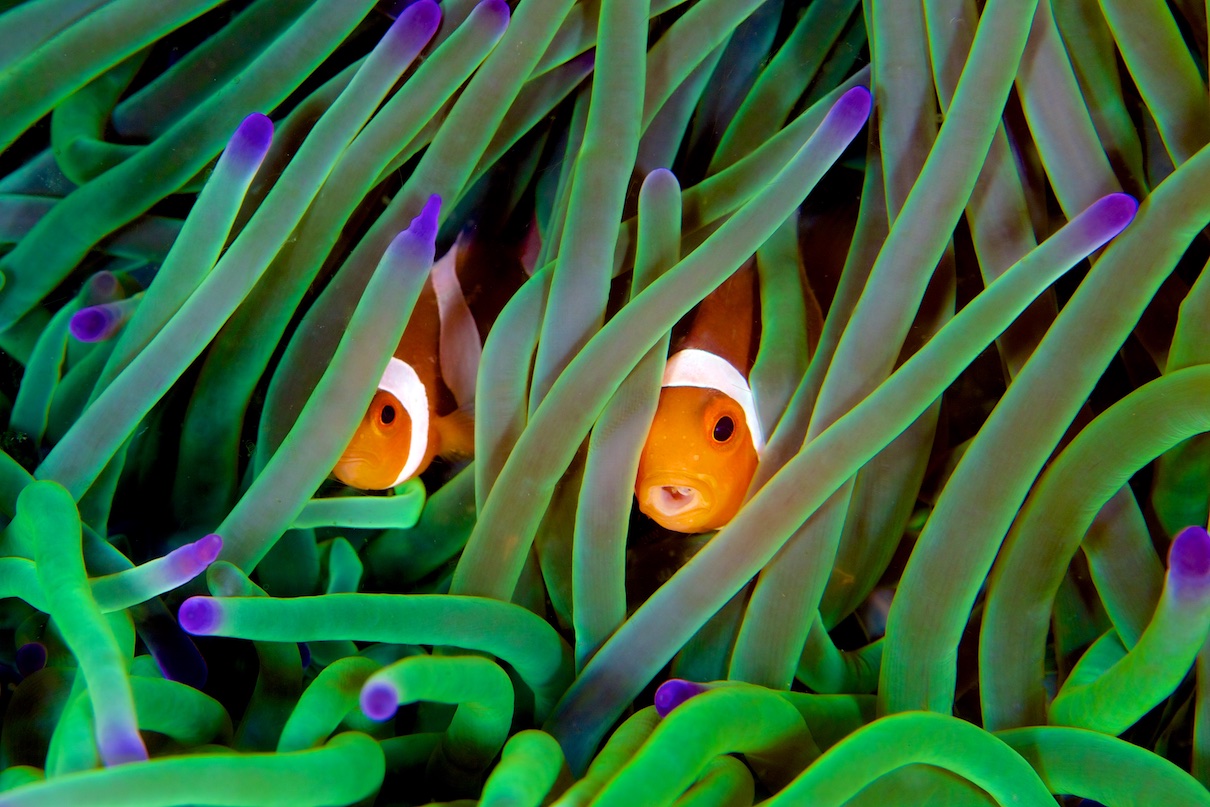

PureCycle’s efforts are part of a push by industries that make and use plastics to develop new ways to address a global scourge of plastic waste that threatens public health and the environment, especially the world’s oceans.

But like other kinds of advanced recycling efforts that have struggled to get out of the gate, like the Brightmark plant in Indiana, or faced serious questions about their commercial viability, like the Encina plant planned for Pennsylvania, PureCycle has its own set of problems.

It fought allegations of fraudulent financial claims until it was cleared by an SEC investigation; encountered serious opposition to a feedstock preparation plant in Florida; lost a key source of feedstock and customers for its basic end product, worrying investors; and has been limited by the Food and Drug Administration in what kinds of plastic waste it can recycle into products that meet food safety standards. Then there are the construction delays at the Ohio plant, which PureCycle has blamed in part on the global coronavirus pandemic.

As of Monday, the Orlando, Florida-based company’s stock had fallen 40 percent since Jan. 23, from $9.36 per share to $5.56.

“They have a serious whack-a-mole problem here,” said Tom Sanzillo, director of finance for the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, and a former New York state deputy comptroller. “Every time they fix something, something else goes wrong.”

“They are up to their neck in debt,” which is common for companies that are trying to expand, he said. “They are juggling a lot of balls and you don’t know how it’s going to land, but you see all these dynamics. They have a cumulative set of risks that are threatening the viability of the company.”

Christian Bruey, a spokesman for PureCycle, said the company would not comment.

A Triple Threat to the Planet

The world is making twice as much plastic waste as it did two decades ago, with most of the discarded materials buried in landfills, burned by incinerators or dumped into the environment, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. Production is expected to triple by 2060.

Globally, only 9 percent of plastic waste is successfully recycled, according to the OECD. The United Nations describes plastic as posing a triple planetary threat of climate change, nature loss and pollution, with the emissions associated with its production and disposal warming the atmosphere and trillions of plastic fragments polluting the air, rivers and oceans and harming species. Microscopic plastic also poses multiple human health risks, entering the body as people consume food, drink water and inhale tiny particles.

The PureCycle technology relies on using chemical solvents to strip away the coloring and chemical additives or plasticizers that give polypropylene special characteristics such as rigidity or pliability. The company says that the end product, polypropylene resin pellets, can then be used to manufacture new polypropylene products.

When the company first announced its technology in 2017, news accounts described the company and its plans as groundbreaking. And in calls with Wall Street analysts as recently as last year, company executives expressed optimism about PureCycle’s future.

The company routinely invokes the global abundance of polypropylene, labeled as a No. 5 plastic, and the threat that the plastic poses to the environment.

“We have to remember, every year approximately 850 billion pounds of plastic and 170 billion pounds of polypropylene are globally produced from fossil fuels,’’ CEO Dustin Olson said in November. “Every year approximately 16 billion pounds of polypropylene is produced in the U.S., and every year less than 5 percent of polypropylene is recycled.”

“The world wants circularity,” Olson added then, using a term for products based on reuse rather than the extraction of natural resources like fossil fuels. “The world wants a new and real plastic solution, and PureCycle is positioned to change the paradigm, and deliver a technical solution that the world so desperately needs.”

However, the company does not lack for critics, among them Jan Dell, a chemical engineer who has worked as a consultant to the oil and gas industry and now runs The Last Beach Cleanup, a nonprofit that fights plastic pollution and waste.

Dell, who has been following PureCycle since it was founded in 2015, said she believes the recent SEC filings may signal the beginning of the end for the company. While there is no shortage of polypropylene waste for potential recycling, she said, this type of plastic is too difficult to recycle into what the Food and Drug Administration would consider safe for use with food products.

“The feedstock is the problem,” she said this week. “The company cannot predict what feedstock they will get” from household recycling bins, where people pitch all sorts of plastics with different chemical makeups. Some discarded plastic bottles may be contaminated by the residue from household hazardous wastes like oil or pesticides.

“It’s like baking a cake,” Dell said. “You don’t come into a bakery with different ingredients every day.”

The variable feedstock complicates a process that relies on toxic solvents to strip away plastic additives in the polypropylene, she said. While the company describes the output as “like-virgin” polypropylene, the FDA has not entirely agreed.

So far, the only post-consumer plastic waste that the FDA will allow the company to recycle into food-grade plastics is drink cups from sports stadiums, a category that Dell describes as a trivial sliver of the polypropylene waste stream. With consumer product companies making promises to use recycled content in much of their packaging materials, focusing on drink cups from stadiums won’t get them very far, she said.

Dell said the actual recycling rate for polypropylene is less than 1 percent, and that the byproduct is typically used to make things like orange plastic traffic cones, though not by PureCycle.

The company announced in 2021 that it had become the official plastics recycling partner of the Cleveland Browns football team, and last year it added the Cincinnati Bengals as a partner. PureCycle has also teamed with the Orlando Magic basketball team to recycle cups.

Keep Environmental Journalism AliveICN provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going.Donate Now