You’re reading The Checkup With Dr. Wen, a newsletter on how to navigate covid-19 and other public health challenges. Click here to get the full newsletter in your inbox, including answers to reader questions and a summary of new scientific research.After my column last week urging the health-care sector to consider the environmental costs of medical care, many readers wrote to ask why I didn’t address the “elephant in the room.” As Bob from Oregon wrote, “Every time I go to the hospital, I see plastic everywhere. Everything’s wrapped in plastic, and then it’s all thrown away. Why aren’t we calling for the health-care industry to reduce their plastics use?”Bob is right. Every day, U.S. health-care facilities generate 14,000 tons of waste. One patient being hospitalized results in nearly 34 pounds of waste every day. Of that waste, up to 25 percent is plastic.Plastics are ubiquitous in health care today, but it wasn’t always that way. Several decades ago, medical supplies were commonly made of metal, cloth and glass. Now, it’s hard to find items that aren’t made of plastics or wrapped in them.The reasons behind that change were justifiable: Busy clinicians prioritize efficiency, and it’s convenient to open a package and find a procedure kit that’s new, sterile and ready to use. Economics played a major role, too, as it’s often cheaper to purchase disposable plastics than to run reusable items through sterilization procedures.But as I discussed before, it should be a major concern to the health-care industry that medical care itself is perpetuating the climate crisis. The pollution the sector causes harms not only the planet but also the health of our patients.Some hospital leaders are showing that cutting single-use plastic use is possible. One bright spot is the switch from disposable plastic gowns to those that can be laundered and reused 75 to 100 times. One study found reusable gowns reduced solid-waste generation by 84 percent and cut greenhouse gas emissions by 66 percent. Another found that these gowns are clinically superior to disposable ones; they are less likely to break and tear and increase infection protection for the wearer.Many hospitals are making this switch. UCLA Health was using 2.6 million disposable isolation gowns every year, generating more than 230 tons of landfill waste. By switching to reusable ones, it dramatically reduced waste and saved an estimated $450,000 annually.As an added bonus, because the UCLA system altered its practice before the pandemic, it did not experience the cost surge of single-use gowns during the height of covid-19 fueled by the global supply-chain disruption and the nationwide run on protective equipment. UCLA hospitals also avoided the critical shortage of gowns faced by other health-care facilities.The Virginia-based Carilion Clinic similarly avoided shortages by stopping its dependence on single-use gowns. Over the first three years after the switch in 2011, it eliminated nearly 515,000 pounds of waste and saved more than $850,000. Another set of Virginia hospitals, the Inova Health System, partnered with a sports apparel company to design and produce custom reusable gowns that are reportedly better fitting, more comfortable temperature-wise and easier to put on and take off.If such changes are better for the environment and reduce costs without negative impacts on patient care, what’s preventing more widespread adoption? One reason is the misconception that reverting to reusable materials will incur more costs or result in greater inefficiencies. Providers and administrators from institutions that have successfully implemented changes should widely share their stories and best practices.Another reason is that incentives are not aligned in favor of the change. Here’s where regulatory agencies can nudge the health-care sector. The Food and Drug Administration can help motivate manufacturers to switch to reusable materials, and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services can be more aggressive in pushing hospitals to meet sustainability goals.There are many single-use plastic products that don’t have an affordable and clinically comparable reusable alternative. Research should focus on designing resilient materials that can be disinfected and reused like metal and glass instruments.As the smoke from the Canadian wildfires has recently reminded us, there is a close tie between the environment and human health. The health-care sector needs to do more to decrease its impact on worsening the environment — and, in so doing, help safeguard our patients’ well-being.Do you know of specific innovations in the health-care sector that are helping to reduce their impact on the environment? I’d love to hear from you. Please keep sending me your comments and questions.

Category Archives: Plastic Pollution Articles & News

Cigarette filters are the world's most common plastic waste

You might not know that cigarette filters are made of plastic. The small, spongy end pieces look a bit like cotton wool, and indeed, some have been made using cotton. But now they’re almost exclusively made of cellulose acetate, a type of plastic. And they’re everywhere.Holly Newman Kroft: Quartz Smart Investing Part 2OffEnglishIn his new book Wasteland: The Secret World of Waste and the Urgent Search for a Cleaner Future, Oliver Franklin-Wallis notes that 480 billion plastic bottles are sold worldwide every year, a number that, laid end-to-end, would circle the globe more than 24 times. That’s a vast number, but, he adds, “It’s not even the most numerous. That dubious honour goes to the four trillion plastic cigarette filters flicked to the ground and stamped out annually.” AdvertisementAs Franklin-Wallis told Quartz, a fairly large proportion of plastic bottles are recycled, at least in the global North, though their material degrades, so it usually can’t be made into new bottles again. But cigarette filters aren’t recycled. And very often, they don’t even make it into the trash: People drop them straight on the ground. “It’s the last remaining acceptable form of littering,” Tom Novotny, an epidemiologist at San Diego State University who has studied the environmental impact of cigarettes, told National Geographic.One reason for this might be the mistaken belief that cigarette butts are biodegradable. In a 2022 study of some 7,500 college-age adults in the US, around a third thought the filters were biodegradable, and a further third didn’t know if they were. The study cites two pieces of observational research on smoker behavior in New Zealand that respectively found almost 99% and 76% of subjects threw their cigarette butts on the ground.AdvertisementAdvertisementCigarette filters and the oceanThe World Health Organization has an even higher number for estimated cigarette butt litter: 4.5 trillion annually. One source for that statistic is beach sweeps, which regularly collect thousands of filters in small stretches of sand. The used ends leach nicotine and heavy metals into the environment, kill marine animals, and damage plant growth. AdvertisementAre there solutions to the problem? Ideally, people need to change their behavior, treating cigarette butts like other forms of plastic waste by throwing them in appropriate bins—though this still won’t make them biodegrade. Europe and some other places are considering banning cigarette filters in an effort to cut both pollution and smoking rates. But before anyone switches to vaping as a less-polluting alternative, that industry is also causing problems. National Geographic noted in 2019 that plastic, single-use vapes and their constituent parts were already piling up on beaches. Franklin-Wallis points out that vapes are now finding their way into recycling so often that they’re causing major problems for the waste industry: When the tiny batteries inside them are crushed or heated, they explode, leading to disastrous fires at recycling facilities.

Inside Indiana's “advanced” plastics recycling plant: dangerous vapors, oil spills and life-threatening fires

ASHLEY, Ind.—Two years ago on a Friday evening in May, Kory Kistler was getting ready to leave work at a recycling plant marketed by its owners as being on the front line in a global war against plastic waste.

Then all hell broke loose. Flammable, 700-degree vapors began spewing from a valve on a pump at the plant.

“All of a sudden my operators on the ground started screaming over the radio,” recalled Kistler, a former Marine and a resident of Fort Wayne, 35 miles to the south. “It was hard to understand anything they were saying. So I was like, ‘I’ll go down, check it out and see what’s going on.’ And as soon as I walk outside, I see clouds of vapor in the sky.”

Then, he recalls, the vapors ignited, setting off an uncontrolled fire that was also fed by a type of oil made from plastic waste in a heated, pressurized chamber. As a black cloud of smoke billowed into the sky, local firefighters raced to the plant, set among farm fields and grain silos in Steuben County along Interstate Highway 69 in northeast Indiana, just west of Ashley, population 1,000.

The plant’s owner is San Francisco-based Brightmark, a company that also works with dairy farmers to capture methane from manure. The plan here, though, is to store, shred and chop plastic waste and extrude it into pellets inside a cavernous building. Those pellets are then fed into pressurized “pyrolysis” chambers—the plant has six of them—that use extreme heat to produce a synthetic gas and a dirty “pyrolysis oil,” in what the chemical industry markets as a type of “advanced recycling.”

Plastic waste at the Brightmark plant in northeast Indiana awaits chemical processing. Credit: James Bruggers

Jay Schabel, president of the plastics division at Brightmark, holds plastic pellets in the company’s new chemical recycling plant in Indiana at the end of July. The pellets are made from plastic waste and sent into chemical processing equipment to make diesel fuel, naphtha and wax. Credit: James Bruggers

The plastics industry champions the process as something that makes plastics sustainable, even green, by turning old plastic containers, packaging and the like into new plastic products without the need to extract more fossil fuels to create new plastic feedstocks. But many scientists and environmentalists say pyrolysis is anything but sustainable, describing it as energy-intensive manufacturing with a large carbon footprint that incinerates much of the plastic waste and mostly just makes new fossil fuels.

“I got down onto the unit and walked over to it,” Kistler recalled, as he described the night of the fire. “There’s just basically a jet fire coming out, so I run as fast as I can screaming for my operator up in the control room to shut the pump off, open everything to the (emergency) flare so we can release dangerous vapor safely and prevent the build-up of pressure.”

But for a while, Kistler said, the pressure kept building and “we started losing all control of the unit along with our safety protocols.”

Eventually, firefighters helped extinguish the flames, and plant operators wrested back control of the plant, according to accounts by Kistler, the Ashley fire department chief and another former Brightmark employee, who was Kistler’s supervisor.

Kistler said he and other plant workers who were in the area when the fire broke out are lucky to still be alive.

“If I had been another foot and a half closer, I probably would not be here talking to you today,” he said on a recent balmy evening sitting outside at a Fort Wayne restaurant. “We were in survival mode.”

For its part, Brightmark calls its proprietary process “plastics renewal,” and its Ashley plant a “circularity center,” using buzzwords that are intended to give it an air of environmental responsibility and sustainability. The company markets itself with children using plastic toys and touts a partnership to remove some plastic waste from the ocean.

But reporting by Inside Climate News reveals the May 2021 fire is just one of several environmental health or safety challenges the company has faced since it began testing its plant in 2020 while struggling to fulfill its promise of operating “the world’s largest plastics renewal facility” on a commercial scale.

An earlier fire in July 2020 threatened the lives of at least three plant workers, according to Kistler and his former supervisor, Roy Bisnett. And an oil spill at the plant in August 2022 took weeks to clean up, public records show.

Another former worker complaining of clouds of plastic dust has sued the company in federal court, claiming lung damage. And a local fire chief says his small volunteer department needs training and new equipment to handle the kinds of fires that occur at refineries and chemical plants, something they had not experienced before.

Company officials declined a request for an interview. In written responses to questions about the fires, the oil spill and plastic dust in the air, company officials said they take environmental health and safety matters seriously.

“The safety of our employees is our top concern,” the statement said. “Because of the nature of our work, we have developed detailed procedures to ensure everyone’s safety, including robust training on critical areas such as operator procedures, emergency response, and lifesaving protocols. We also run tests regularly to identify other improvements.”

But to an independent oil and gas industry expert like Jan Dell, an engineer who has consulted in more than 45 countries, the environmental, health and safety problems at Brightmark can be expected in a new industry populated by small, start-up companies grappling with difficult-to-impossible technical challenges and highly combustible plastic residues. They are an indicator, Dell said, of why “advanced” or “chemical” recycling of plastics won’t work and actually risks lives.

“They are dangerous chemical facilities that should be regulated as dangerous chemical facilities,” said Dell, who founded and runs The Last Beach Cleanup, a Southern California nonprofit that fights plastic pollution and waste. “They are putting workers, firefighters, and the community at risk.”

In Two and a Half Years, Dashed Hopes

Brightmark broke ground on its Ashley plastics plant in 2019, after purchasing the technology from Ohio-based RES Polyflow the year before. Ashley is about a half mile west of the plant. Its main drag is lined with aging storefronts and American flags. A bright yellow water tower featuring a smiley face and bowtie rises from a city park.

Ashley, Indiana, is known for its yellow smiley face water tower. The Brightmark chemical recycling plant is nearby. Credit: James Bruggers

A Brightmark billboard near Ashley, Indiana. Credit: James Bruggers

Last summer, on a tour of the plant, Jay Schabel, president of the plastics division at Brightmark and the former RES Polyflow CEO, described his hope to “change the world.”

The facility has three main parts. There is a 120,000-square-foot warehouse where hundreds of tons of mixed household and industrial plastic waste is collected, picked through and sent into a mechanical process to make the pellets. Then, the pellets are sent into pyrolysis chambers, where they are heated to as much as 1,500 degrees in a zero-oxygen environment by burning natural gas and synthetic gas made from plastic waste to make “pyrolysis oil.” The pyrolysis oil then goes to a refinery behind the warehouse, where it’s separated into low-sulfur diesel fuel, liquid naphtha that can be used as a feedstock for new plastic and wax for industrial uses or candles.

In a December 2020 year-end wrap-up, Brightmark founder and chief executive officer Bob Powell celebrated a milestone and promised big things—and quickly.

“We have now financed and built our $260 million, first-of-its-kind plastics renewal facility in Ashley, Indiana,” he wrote. “Our plant is now producing liquids, which was a huge moment for our team. Beginning in (the first quarter) next year, the plant will accept 100,000 tons of plastics each year for conversion into new products – a vastly greater scale than any other facility of its kind in the world.”

But the plant is still trying to move beyond the start-up phase.

Former company employees said in interviews that they believe the company has a poor environmental health and safety record. They said they’re afraid that current employees could be at risk and they questioned whether Brightmark will live up to its promise. They describe an internal culture in which managers allegedly resisted the development of written procedures, took shortcuts that compromised safety and gave short shrift to the kinds of safety procedures common in a chemical plant or refinery run by a large, established company.

One of them, Roy Bisnett, was hired in 2020 to run the plant’s chemical and refinery operations. A Toledo-area resident, his experience was in oil refining and managing environmental health and safety initiatives, working on staff with oil companies or as a consultant.

“I thought this was a very, very interesting thing,” Bisnett said of what Brightmark was trying to accomplish. “There’s a plastic waste issue. I’m in the refining industry, and we can turn this waste into a fuel. It sounded great.

“They said it was proven technology, right? It was already built for the most part. We’d bring people in and train them to get it operating,” he recalled.

Bisnett said he was excited about the company’s ambitions to take the technology to other parts of the United States and the world, which made it seem like a good opportunity for career growth, Bisnett said.

It didn’t work out that way.

“Fast forward two and a half years, we were still in the same boat but with a lot of mistakes,” said Bisnett, who said he resigned in 2022 because of differences in philosophies over environmental health and safety matters.

He also said it was hard to reconcile the company’s environmental marketing with its environmental and safety performance, citing fires, the handling of the 2022 oil spill, the plastic dust issues and a lack of attention to what he called process safety management and improvement.

“Over the course of my time in the refining industry, we have always strived to learn from past mistakes, in an effort to not repeat them,” he said. “At Brightmark, this was not the case.”

The Brightmark chemical recycling plant in Ashley, Indiana. Credit: James Bruggers

For his part, Kistler worked for the company about as long as Bisnett in the same department and was, as Kistler described, Bisnett’s “right hand man.” Brightmark fired Kistler in late 2022, and on May 25, Kistler filed a lawsuit in Indiana state court, claiming wrongful termination and retaliation over a worker’s compensation claim that stemmed from a shoulder injury he suffered on the job.

In an interview, Kistler said Brightmark fired him in part “because I started asking questions and making noise about health, safety, environmental and personnel issues.”

Brightmark said it does not comment on legal matters.

But the company defended its technology, which it says “has been refined over 20 years, making the company a veteran among more nascent technologies in the marketplace. Our circular solutions play a unique role in recapturing the value in waste plastics and returning those raw materials into the circular economy, reducing dependence on virgin fossil fuels for manufacturing products that require plastic.”

Spectacular Blazes With More Intense Heat

Plastic is made from fossil fuels, and fires at plastic recycling facilities can produce spectacular blazes with intense heat and billowing black, toxic smoke, as residents of Richmond, Indiana, in the southwest part of the state, found out in April. There, a stockpile of plastic waste burned for days and 2,000 people were told to evacuate their homes.

So far, the fires at Brightmark have been associated with its chemical plant operations, not its stockpile of waste plastic in the warehouse, according to interviews with former employees and a local fire official.

Nevertheless, the plant has kept the Ashley Hudson Fire Department of about 20 members busy, responding to at least six or seven fires since 2020, at least one producing a plume of smoke that could be seen 35 miles away in Fort Wayne, said its Fire Chief Dave Barrand.

“They were in the middle of start-up testing. They were changing out some components and it started spontaneously, combusted and burned up a brand new forklift,” Barrand recalled of the July 2020 fire.

Bisnett said the fire broke out during one of the first tests of a pyrolysis chamber, sending a jet of flames “out the end of the pyrolysis reactor.” The fire could have been avoided by first conducting a safety check under common industry protocols known as process safety management, he said.

The fire could have been much worse, causing serious injuries or death, Bisnett said, “if the employees hadn’t changed their location just prior to the blowout.”

One of Bisnett’s concerns at the time, and today, is that local firefighters, who are more accustomed to fighting house or small commercial building fires, do not have the training or equipment needed to fight fires at chemical plants or refineries, such as the Brightmark facility. Water can make chemical fires worse, he said. And sometimes a chemical plant fire can be extinguished, but the source, a fast-blowing stream of flammable vapors, can remain, creating a new explosion hazard, he said.

Austin Acker, a volunteer firefighter, cleans a fire truck at the Ashley, Indiana volunteer fire department firehouse in May 2023. Credit: James Bruggers

Barrand agreed and said his department could use a new, larger ladder truck, which could cost as much as $1 million, to reach higher areas in the Brightmark facility, he said. That would allow firefighters to also stay farther away from the heat, which can be more intense in a chemical plant fire, he said. Also, the department could benefit from more fire-retardant foam to fight chemical plant fires and specialized training.

“It’d be kind of nice for all of the department to go and get some kind of refinery training,” Barrand said. “I think I was looking at right around $30,000 or $40,000 to send five people to Texas to get trained.” That would be $120,000 to $180,000 for the department.

He said there has been “some conversation” with Brightmark about the company paying to help with the costs of being ready to fight fires at their plant. “I don’t know how far that went,” he added.

When asked whether the company feels an obligation to assist local firefighters in upgrading their capacity to fight chemical plant fires, Brightmark spokeswoman Aunny De La Rosa-Bathe said: “Brightmark values all the services our local municipality in Ashley provides to support our mission to reimagine waste. Our flagship Circularity Center is equipped with substantial fire prevention and protection equipment throughout.”

A Slow Oil Spill Response and Lawsuit Over Plastic Dust

In addition to fires, former workers describe oil spills and poor indoor air quality as recurring problems.

Public records show at least one spill was reported to the Indiana Department of Environmental Management on Aug. 7, 2022, with initial and subsequent records showing conflicting accounts of its size, from 170 to 366 gallons.

Barry Sneed, a spokesman for the Indiana Department of Environmental Management, said that no violation or fine was issued because the spill occurred within a facility and “a spill response was initiated.”

Both Kistler and Bisnett said they believe the spill was substantially larger.

Kistler said he had found a contractor who could have cleaned up the spill within a week, but was overruled by management that opted for a slower but less expensive response.

Brightmark acknowledged that the availability of a contractor “contributed to the delay. We have since partnered with other third parties to facilitate the process should the need arise. All reportable spills have been reported to required government agencies.”

An oil spill at Brightmark that was reported to the Indiana Department of Environmental Management. Credit: Kory Kistler

Poor air quality inside the warehouse was another problem.

Doug King, who lives in Coldwater, Michigan, 30 miles north of the plant, said he worked for Brightmark for about two years, starting in the fall of 2020, and, like Bisnett, had high hopes of being part of a solution to the plastics problem.

He left the company in May 2022, disillusioned, and having a hard time breathing. He has since filed a federal lawsuit claiming lung damage. He claims Brightmark wrongfully terminated his employment after he brought his health and safety concerns to company management.

Brightmark denied King’s claims in a Dec. 15, 2022 court document, writing that the company “acted in good faith at all times, and all decisions or actions regarding (King’s) employment were pursuant to its legitimate business purpose and for non-retaliatory business reasons.”

The case recently went to arbitration, according to court records.

Keep Environmental Journalism AliveICN provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going.Donate Now

Cities turn to trash skimmer boats to clean local waters

Cities are turning to “trash skimmers” to rid their waterways of plastic waste. But environmentalists say the boats are more of a Band-Aid than a solution.via City of TampaAs plastics accumulate in rivers and bays, localities across the country are seeking creative, affordable solutions to keep their waterways clean. Many have turned to “trash skimmers,” boats that are designed to remove litter.Tampa, Fla., is one of the latest cities to invest in such a vessel, a $565,000 boat that it has named the “Litter Skimmer.” It skims single-use plastics and other trash — as well as organic materials such as branches and leaves — from the water and onto a conveyor belt that pulls it into a storage area, a city spokesman said.The boat debuted about a year ago and has since gathered about 13 tons of debris, said Alexis Black, an environmental specialist with Tampa’s Department of Solid Waste and Environmental Program Management.As far back as the 1950s, scientists have been warning that marine life was getting stuck in discarded fishing gear and other types of plastic waste. Since then, consumption of single-use plastics has risen to the point where tens of millions of tons of plastic enter Earth’s oceans each year. Over the years, plastics have harmed local ecosystems and disrupted storm water management, leading to flooding.The skimmer is only one method that Tampa is using to remove waste from its local waters. The city also organizes community cleanup events along its waterways and in its parks, and uses tools like baffle boxes and netting to keep debris from leaving storm drains and going into the river.“The introduction of Litter Skimmer was just to add an extra layer of the strategy to combat the litter that makes it into the water bodies,” Ms. Black said. “It’s a great step to capture a lot of the waste that in the past was just left to float down the river in the bay and beyond.”Trash skimmers have long been part of municipal efforts to clean up waterways. Washington, D.C., began using skimmer boats in 1992 and added two more to its fleet in 2017, for $484,000 each. The Passaic Valley Sewerage Commission in New Jersey unveiled its first trash-collecting vessel in 1998 and purchased a second in 2018 for about $653,000.D.C. Water, Washington’s water utility, said that its boats collect 300 to 500 tons of waste each year. The Passaic Valley Sewerage Commission said its boats gather 160 tons of waste annually.Carroll Muffett, president of the Center for International Environment Law, a nonprofit that focuses on environmental issues, said the skimmer boat programs are well-intentioned, but such efforts do little to address the overall problem of plastic pollution.While skimmers are designed to collect larger pieces of floating trash, many plastics are too small for the vessels to capture, Mr. Muffett said. A 2019 study from the University of South Florida St. Petersburg and Eckerd College estimated that four billion particles of microplastics — which are less than one-eighth of an inch long — are in the Tampa Bay.Most municipal skimmers also have limited hours of operation, Mr. Muffett said. The skimmer in Tampa, for instance, runs 10 hours a day, four days a week, typically operated by two people.“You begin to understand that this is only a tiny Band-Aid on what is a massive problem,” he said. “What it also represents is the massive investment that cities, counties and states are making in cleaning up this problem.”There isn’t just a policy responsibility; it’s a personal one as well, said John Atkinson, an associate professor of civil, structural and environmental engineering at the University at Buffalo.“We’re a culture that is reliant on plastic,” Professor Atkinson said, adding that “choosing to use a reusable water bottle, while small, can be substantial if everybody chooses it.”Policies that reduce the overall use of plastic, such as bans on single-use disposable plastics, would be more effective, he said.“We cannot scoop, we cannot shovel, we cannot net, we cannot recycle our way out of the plastics crisis,” Mr. Muffett said. “The only way we address the plastics crisis is by producing — and using and losing — fewer plastics.”

Why you should stop using laundry pods right now

Doing right by the planet can make you happier, healthier, and—yes—wealthier. Outside’s head of sustainability, Kristin Hostetter, explores small lifestyle tweaks that can make a big impact. Write to her at climateneutral-ish@outsideinc.com.

Oh, the irony. In trying to wash my clothes the green way, I was greenwashed. You might even say I was taken to the cleaners. Or hung out to dry.

Let me explain: more than a year ago, I learned that laundry pods—encased in dissolvable plastic—were bad for the environment. In my quest to find more sustainable, plastic-free household products, I was thrilled to come across laundry “eco-strips,” as an easy swap-out. Instead of the typical plastic jug, the thin compressed sheets are packaged in a recyclable cardboard envelope and marketed as plastic-free. I promptly ordered a year’s supply and told everyone who would listen about my new discovery.

My latest preferred laundry kit, clockwise from top: lavender essential oil, soap nuts in a muslin sack, and wool dryer balls. (Photo: Kristin Hostetter)

Imagine my surprise when I discovered that what holds those innocuous little strips together is a sneaky type of plastic called polyvinyl alcohol, or PVA. It’s the same exact stuff that encases laundry (and dishwasher) pods, and though it’s designed to dissolve as soon as it hits water, it is indeed plastic. A very controversial type of plastic. To learn more about PVA and come up with sustainable alternatives, I connected with Dianna Cohen, co-founder and CEO of Plastic Pollution Coalition, a nonprofit working towards a world free of plastic pollution and its toxic impacts.

The PVA Controversy

PVA is a water-soluble synthetic polymer (a fancy word for plastic that readily binds itself to water molecules). You’ll find it on the ingredient list of virtually every laundry or dishwasher pod and every laundry sheet or strip. PVA has excellent barrier properties, so it’s good at holding together liquids and other squishy stuff, like soap. It’s also really good at dissolving. That’s why it vanishes in our washing machines and dishwashers. But does it really disappear? “When you stir a spoonful of sugar or salt into water, it dissolves, but is it gone?” Cohen asks. “Take a taste and you have your answer. It’s the same with PVA.”

The dissolved PVA slides right down the tubes and off it goes to the treatment plant with your dirt, suds, and wastewater. What happens next depends on who you ask.

According to the American Cleaning Institute, PVA polymers are “fully biodegraded by microorganisms in water treatment facilities and the environment.” But Cohen, a slew of other leading advocates for clean oceans, and this 2021 study in The International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health which looks at PVA degradation U.S. wastewater treatment plants, say that is simply not the case. “There is a serious lack of unbiased research on the human and environmental health effects of PVA,” says Cohen because existing research was funded by companies with biased interests. “We do, however, know that PVA has been found in human breast milk and in fish, which indicates that it does not simply vanish in wastewater treatment plants. It’s making its way into our bodies and our environment.”

Plastic Pollution Coalition, as well as many other advocacy groups like like Plastic Oceans, Beyond Plastics, and 5 Gyres, contend that we simply don’t know enough about the effects of PVA—which is why the groups have come together to call on the EPA to conduct an independent study to figure it out. “We need the EPA to take swift and urgent action to study the full ecological and health impacts of PVA in order to best protect people and our planet from potential harm,” says Cohen. The group has currently collected close to 23,000 signatures on a petition to get the EPA to conduct extensive tests on PVA biodegradability and its potential impact on the environment and human health. They want a few thousand more. You can add your name here.

Laundry Soaps That Are Truly Plastic-Free

So what’s an environmentalist to do? First, avoid buying detergent in plastic containers. Second, check the ingredient list and if you see a lot of long, chemical-ish words, be suspicious. These things are bad: optical brighteners, chlorine, formaldehyde, synthetic nonylphenol ethoxylates, phosphates, phthalates. Third, if you have a refill shop near you, BYO containers and support it. We need the concept of refill shops to catch on in U.S.

Cohen helped me come up with a few green detergent ideas, all of which are quite affordable.

DIY Laundry Soap

Combine 14 ounces of washing soda, 14 ounces of borax, or baking soda, with 4.5 ounces of natural castile soap flakes. Store the mixture in a sealed glass jar. Use one to three tablespoons per load, depending on size.Cost: about .10 per load.

Soap Nuts

I’ve been using these for several weeks with good results. Just put five to seven nuts (which are really berries) into the included muslin sack and toss in the wash. The shells contain saponin, a natural soap which releases into the water. Soap nuts don’t generate a lot of suds (because they lack the chemical foaming agents we’re used to) and they’re not for tough stains. But for regular use, they’re pretty cool. You can use soap nuts five to eight times before the saponin wears off. Compost the spent nuts and replace with new ones. I’ve been adding a few drops of lavender essential oil to the bag to give my laundry a light fragrance—the nuts alone are odorless.Cost: about .23 per load.

Meliora Laundry Powder Detergent

This powder also gets my thumbs up. Made with non-toxic ingredients and shipped in curbside recyclable packaging, it comes in several all-natural scents. Meliora also makes a Soap Stick Stain Remover, which I use to rub any tough spots before washing.Cost: about .23 per load

More Sustainable Laundry Tips

Choosing a non-toxic, plastic-free detergent isn’t the only way to green up your laundry process. Here are some other tips.

Wear Clothes Longer

Don’t mindlessly toss clothes into the hamper after a wear. Ask yourself if those jeans really need washing, or can you fold them up and wear them again?

Turn Clothes Inside Out Before Washing

This will make your clothes last longer by protecting colors from premature fading and preventing snags during laundering.

Fill the Machine

Say no to half loads; they waste water and energy.

Use Cold Water

Unless your clothes are really dirty, go for the cold wash. You’ll save money and energy, and your clothes will last longer and shed fewer microfibers, which is another environmental concern.

Air Dry

Like cold-washing, air drying will also save you money and energy, even if you partially air dry and then finish it off in the dryer to release wrinkles.

Skip the Dryer Sheets

Yep, they contain PVA, too. I’ve been using wool dryer balls for over a year and they do a fine job of releasing wrinkles, fluffing things up, and reducing (most, but not always all) static.

Avoid Dry Cleaning

You know that distinctive smell that hits you when you walk into a dry cleaner? Those are chemicals. Most dry cleaners use a host of toxic chemicals and petroleum-based solvents that can be harmful to humans and the environment.

Kristin Hostetter is the head of sustainability at Outside Interactive, Inc. and the resident sustainability columnist on Outside Online.

Geoffrey Lean: Whisper it, but the boom in plastic production could be about to come to a juddering halt

Plastic production has soared some 30-fold since it came into widespread use in the 1960s. We now churn out about 430m tonnes a year, easily outweighing the combined mass of all 8 billion people alive. Left unabated, it continues to accelerate: plastic consumption is due to nearly double by 2050.Now there is a chance that this huge growth will stop, even go into reverse. This month in Paris, the world’s governments agreed to draft a new treaty to control plastics. The UN says it could cut production by a massive 80% by 2040.Such a treaty – scheduled for agreement next year – cannot come soon enough.The amount of plastic dumped in the oceans is due to more than double by 2040. Producing single-use plastic alone emits more greenhouse gases than the whole UK. And microplastics have been found in human blood, lungs, livers, kidneys and spleens – and have crossed the placenta. No one knows the full effects on the planet – or the impact of the 3,200 potentially harmful chemicals in plastics on our health.Governments finally began to call a halt in March last year, resolving to “end plastic pollution” at a meeting of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and calling for a series of negotiating meetings on a possible treaty. The recent meeting in Paris was the second such “plastic summit”. Three more are scheduled before the end of next year.Whisper it, but – with hard work, determination and a lot of good luck – the plastics treaty might join the Montreal protocol on substances that deplete the ozone layer as a landmark success in environmental diplomacy.It has several important advantages. It is backed by immense public concern – uniting a whole range of issues from litter to the oceans, human health to climate breakdown – which can be translated into political pressure. And no new technology is needed: UNEP says the 80% reduction can be achieved using proven practices.These include simply eliminating much unnecessary single-use plastic packaging, ensuring reuse, and replacing many instances of plastic use with more sustainable biodegradable materials. Governments could also discourage the production of new plastics by taxing it and removing industry subsidies.Crucially, like the negotiations over ozone, it has some strong business support. A 100-strong Business Coalition for a Global Plastics Treaty – which includes giant users of plastics such as Unilever and Coca-Cola – is pressing for tough regulatory measures.And, as in recent successful UN agreements, an alliance of governments committed to change is leading the charge. This High Ambition Coalition includes all G7 countries except Italy and the US. Importantly, Japan – which had opposed a strong treaty – recently switched sides to join it.UNEP also has a good record of cementing treaties. It has brokered a host of pacts, covering issues from wildlife to toxic wastes, and the historic Montreal protocol.That protocol – the first treaty to be ratified by every country on Earth – has phased out the use of nearly 100 substances that attack the planet’s protective ozone. As a byproduct, it has done more to slow climate breakdown than any other international agreement, since many of those substances also heat the atmosphere.None of this means it will be easy. When I was reporting the story, I was told that agreeing the Montreal protocol was so dicey that the text could not immediately be translated from English into the other five official UN languages for fear of upsetting its delicate verbal compromises.Weighty, determined opposition to radical measures comes from a powerful minority of plastic-producing countries including China, India and the US. And companies that have obstructed action on global heating are mobilising. Ninety-nine per cent of plastics are made with fossil fuels and the industry is determined to expand their production to offset what it is losing to clean sources of energy.There are three main sources of contention. The majority of countries want binding global rules, while their opponents insist on voluntary ones. Most countries want to limit plastics production and ban dangerous substances, while the manufacturers focus on recycling what is produced.And the majority want decisions to be made by vote, while many of those opposed want to keep a veto by demanding consensus. This issue held up substantive talks in Paris for two days, and is still unresolved. And beyond all this lies the ever-thorny question of who will pay for the change.All in all, some kind of treaty is likely to emerge. How strong and effective it is will depend on how these issues are settled.

Geoffrey Lean is a specialist environment correspondent and author

Satellites, drones join fight against air pollution in Pennsylvania

A cluster of colors indicates methane gas released from a coal mine vent in Pennsylvania. (Carbon Mapper)

In the summer of 2021, a twin-engine special research aircraft took off from State College, PA. Over three weeks, the plane flew 10,000–28,000 feet over oil and gas wells, landfills and coal mines in four regions of the state. The mission was to pinpoint sources of high levels of methane gas, or “super emitters,” for the nonprofit group Carbon Mapper and its funding partner, U.S. Climate Alliance.From a hole cut in the belly of the plane, they trained a camera-like device developed by NASA — an imaging spectrometer — that uses light wavelengths to pick up escaping plumes of methane. Methane emissions are the second-largest cause of global warming after carbon dioxide, and controlling them is increasingly considered a key to arresting climate change.

Methane is invisible to the naked eye. But spectrometers, and devices like them, detect and measure the infrared energy of objects. The cameras then convert that data into a three-dimensional electronic image.For the 2021 aerial probe, Carbon Mapper targeted areas of generally high methane levels that the organization had previously located using readings from space satellites operated by the European Space Agency.During the flights, the researchers found 63 super emitters. Most, they concluded, were the results of leaks and malfunctioning equipment.The Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection, which collaborated in the project, was thrilled by the reactions they received when they took the results to the sources of the highest emissions. The operators of six landfills and six oil and gas wells responded by voluntarily fixing equipment or taking other steps to reduce emissions.“That’s a really positive thing. This is existential proof that making methane visible can lead to voluntary action,” said Riley Duren, Carbon Mapper CEO and founder.In Pennsylvania, the use of this and other technology has energized a new breed of environmental activism aimed at detecting air pollution from the sky and from the ground. Their tools include satellites, airplanes with specially equipped air monitors and ground-based remote-sensing cameras like those used by government regulators and gas operators to find leaks.Sometimes, communities and groups use these devices to document problems. They also use them to document air quality before gas wells or petrochemical plants are built.“It’s not our parents’ or grandparents’ environmentalism. It’s definitely not just sitting in trees. It’s a different type of environmentalism and it’s much more sophisticated,” said Justin Wasser of Earthworks, a national environmental group that helps communities fight oil, gas and mining pollution.High tech eyesLater this year and in early 2024, Carbon Mapper and its partners, which include NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and Planet Labs, plan to launch two satellites to monitor methane emissions around the world. The first phase of the monitoring program has a $100 million budget, all funded by philanthropy.Also early next year, a satellite dubbed MethaneSAT, funded by such high-profile financial backers as Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos, is scheduled to begin orbiting the Earth to monitor methane emissions.“Methane satellites are going to dramatically change this work. This time next year, you and I are going to be talking about how astronomically large this problem is and why we haven’t been working on this for years,” Earthwork’s Wasser said.Since 2020, the Pennsylvania-based group, FracTracker Alliance, has used ground monitors in southwestern Pennsylvania to document the cumulative effect of air pollution from fracking wells and petrochemical plants.

Colored blobs from an imaging spectrometer operated from an airplane indicate methane gas releases from a natural gas well pad (top) and from vents in a coal mine (bottom) in Pennsylvania. (Courtesy of Carbon Mapper)

Now, armed with a $495,000 federal grant from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, the group has purchased a drone that will carry infrared cameras over wells and gas-related petrochemical plants, looking for methane releases as well as smog-forming chemicals and volatile organic compounds. The grant is part of a new federal initiative to enhance air quality monitoring in communities across the U.S.“This kind of camera never seemed possible before. It seemed like a wish list,” said Ted Auch, FracTracker’s primary drone operator. “We’ll be deploying drones in a lot of hard-to-reach spots like up a hill, in a hollow, around a corner. We can pinpoint smokestacks.”The group hopes that the data it yields will bolster the group’s stance that new gas well permits should be granted only after considering an area’s cumulative air quality, executive director Shannon Smith said.Christina Digiulio, a retired analytical chemist now working for the Pennsylvania chapter of Physicians for Social Responsibility, gets busy when she fields a health complaint from a resident living near a gas well, gas-based petrochemical plant or a landfill that’s accepting fracked-gas waste.A certified thermographer, she lugs a $100,000 gas-imaging forward-looking infrared (FLIR) camera to a gas well pad or the fence line of an industrial plant to look for plumes of methane and volatile organic compounds.“We are using technology now that the industries have kept to themselves. We are an extension of our own regulatory agencies,” she said.

This infrared camera was used to capture images of methane escaping a natural gas well in Lycoming County, PA. (Courtesy of Earthworks)

Getting resultsEnvironmental groups that share findings from their high-tech devices with regulators and gas operators report mixed results.After the 2021 flights departing from State College, Carbon Mapper found that 60% of the methane releases documented were coming from vents in active and old underground coal mines — more than from oil and gas sources combined. Although venting is allowed to prevent the buildup of gases for safety reasons, regulators and researchers alike were surprised at the volume.But the coal industry did not cooperate in measuring emissions from the mines and threatened criminal trespass charges for flying over them, DEP’s Sean Nolan told the agency’s Air Quality Technical Advisory Committee.For the past two years, Melissa Ostroff, a thermographer for Earthworks, has roamed Pennsylvania with a handheld FLIR camera looking for fugitive methane and other invisible pollutants leaking from hundreds of active and abandoned oil and gas well sites as part of the group’s Energy Fields Investigations team.Of 52 instances of methane leaks she has reported to DEP, the agency sent someone to inspect the sites 31 times. Often, she said, equipment malfunctions causing the emissions were fixed.

A camera that sees infrared lightwaves captured this daytime image of methane emissions (the orange “smoke”) from a gas-fired power plant in Pennsylvania. These emissions are not visible to the naked eye. (Physicians for Social Responsibility PA)

In one of her most visible investigations, Ostroff found a gas well leaking methane gas in a popular park in Allegheny County. She reported the pollution to both the gas company and DEP. Within days, the leak was repaired with new equipment installed.Digiulio once detected emissions coming from a compressor station on a liquid natural gas pipeline being built in the eastern part of the state. She notified her state senator, who determined that the company did not have a permit for releases. Work stopped until a permit was obtained.But some environmental groups said that their reports to regulators of unauthorized pollution go unchecked or that operators are allowed to fix problems without being cited for violations.On May 11, the Environmental Integrity Project and Clean Air Council filed a federal lawsuit to halt illegal releases of pollutants from a massive Shell plant using natural gas to produce plastics near Pittsburgh.The groups cite unpermitted releases of pollutants recorded, in part, by high-tech air monitors that Shell agreed to install as part of a previous settlement agreement.Funding boostsThe increased use of citizen science is getting support from the federal government.Under the EPA’s proposed new nationwide rules to regulate methane gas, oil and gas drillers would be required to act on potential leaks at super emitter sites found by third parties, such as environmental nonprofits, universities and others.In a separate initiative, the EPA has announced $53 million in grants in 37 states, including the Chesapeake Bay states of Pennsylvania, Virginia, Maryland, New York and West Virginia, to fund grassroots monitoring efforts in communities. The money will help pay for the purchase and deployment of various devices communities can use to detect air pollution, emissions and possible causes of health problems.

Melissa Ostroff, a licensed thermographer for the environmental group Earthworks, uses an infrared camera to detect methane leaks from a natural gas well in Pennsylvania.(Courtesy of Earthworks)

Pennsylvania will receive 11 grants under the program, with four supporting work by the Environmental Health Project to analyze air quality data as well as helping communities to understand it. A grant to the Maryland Department of the Environment will help reduce air pollution found by sensors in three environmental justice communities, and Virginia will receive two grants to enable the Upper Mattaponi Indian Tribe to set up an air quality program in their community.The aid for monitoring “will finally give communities, some who for years have been overburdened by polluted air and other environmental insults, the data and information needed to better understand their local air quality and have a voice for real change,” said Adam Ortiz, EPA administrator for Mid-Atlantic region.Though thrilled to access equipment that can help amass hard evidence of pollution, some environmental groups are wary that they may have an increased role in protecting public health when it is the responsibility of government agencies to do just that.“The data does not have the weight of EPA’s Clean Air Act’s requirements,” said Nathan Deron, the environmental data scientist for the Environmental Health Project. “At the end of the day, it’s up to DEP and other state regulators to listen to communities and act on the data that is being gathered.”“We have more advanced technology. The gas industry does, too. But that, in itself, is not enough to influence policy if the political will isn’t there,” FracTracker’s Smith added. “We want to influence regulators to put in more protections.”

World Ocean Day: How much plastic is in our oceans?

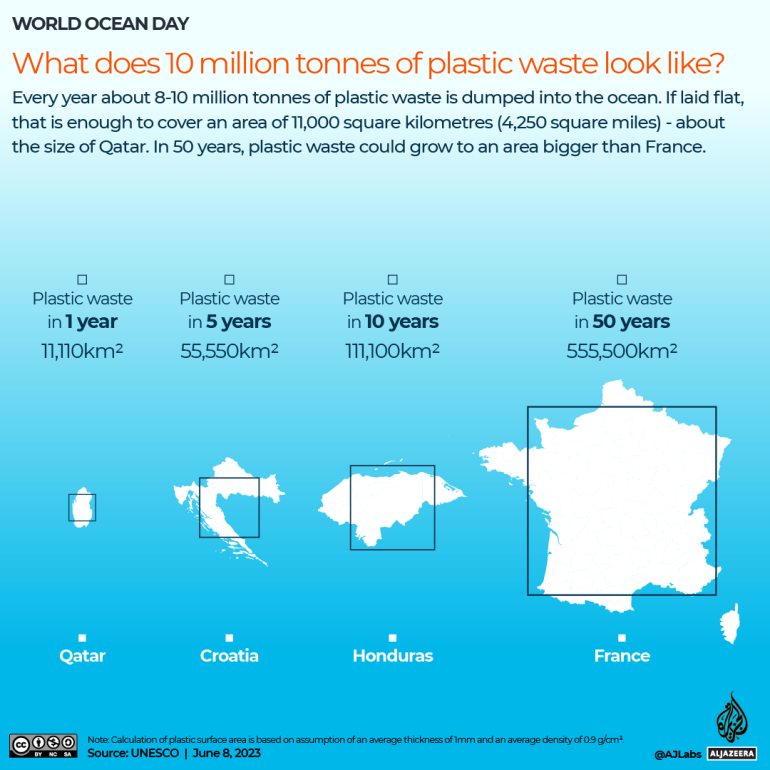

According to UNESCO, 8-10 million tonnes of plastic are released into the sea every year. On World Ocean Day, Al Jazeera visualises what that looks like.Every year, about 400 million tonnes of plastic products are produced around the world. About half are used to make single-use items such as shopping bags, cups and packaging material.

Of these plastics, an estimated 8 million to 10 million tonnes end up in the ocean each year. If flattened to the thickness of a plastic bag, that is enough to cover an area of 11,000sq km (4,250sq miles). That is about the size of small countries like Qatar, Jamaica or the Bahamas.

At this rate, over the course of 50 years, plastic waste could grow to an area bigger than 550,000sq km (212,000sq miles) – about the size of France, Thailand or Ukraine.

To raise awareness about the importance of the ocean and promote its sustainable use and protection, the United Nations designated every June 8 as World Ocean Day.

(Al Jazeera)

How does plastic end up in the ocean?

Plastics are the most common form of ocean litter, comprising 80 percent of all marine pollution. Most plastics that end up in the ocean come from improper waste disposal systems that dump rubbish in rivers and streams.

Plastics in the form of fishing nets and other marine equipment are also dumped into the ocean by ships and fishing boats.

Besides plastic bags and containers, tiny particles known as microplastics also make their way into the ocean. Microplastics, which are less than 5mm (one-fifth of an inch) in length, are a major environmental concern because they can be ingested by marine life and cause harm to both animals and humans.

An estimated 50 trillion to 75 trillion pieces of microplastics are in the ocean today.

(Al Jazeera)

While research on the health effects of human consumption of microplastics is limited, some studies have indicated that microplastics can accumulate in organs such as the liver, kidneys and intestines. There are concerns that microplastic particles could potentially lead to inflammation, oxidative stress and cellular damage.

“These little particles in the ocean were breaking into little pieces and being consumed by the wildlife living there at an almost unimaginable scale. The main problem is that pieces of plastic contain toxic chemicals and these chemicals are already known to interfere with human hormones and animal hormones. They may cause the accumulation of toxins in the body that may lead to ill effects over time,” science writer and author Erica Cirino told Al Jazeera’s The Stream programme.

Which countries are the source of the most plastic in the ocean?

According to a 2021 study published by Science Advances research, 80 percent of all plastics found in the ocean comes from Asia.

The Philippines is believed to be the source of more than a third (36.4 percent) of all plastic waste in the ocean followed by India (12.9 percent), Malaysia (7.5 percent), China (7.2 percent) and Indonesia (5.8 percent).

These amounts do not include waste that is exported overseas that may be at higher risk of entering the ocean.

(Al Jazeera)

What makes plastics so dangerous for the environment?

Plastics are synthetic materials made from polymers, which are long chains of molecules. These polymers are typically derived from petroleum or natural gas.

The main problem with plastics is that they do not easily biodegrade, which means they can persist in the environment for hundreds of years, causing serious pollution problems.

Plastics that find their way into the ocean end up floating on the surface for a long time. Eventually, they sink to the bottom and get buried in the seafloor.

Plastics on the surface of the ocean represent 1 percent of the total plastics in the ocean. The other 99 percent are microplastic fragments far below the surface.

Plastic bottles, wooden planks, rusty barrels and other rubbish clog the Drina river near the eastern Bosnian town of Visegrad on May 25, 2023 [Eldar Emric/AP]

World Ocean Day: How much plastic is in our oceans?

According to UNESCO, 8-10 million tonnes of plastic are released into the sea every year. On World Ocean Day, Al Jazeera visualises what that looks like.Every year, about 400 million tonnes of plastic products are produced around the world. About half are used to make single-use items such as shopping bags, cups and packaging material.

Of these plastics, an estimated 8 million to 10 million tonnes end up in the ocean each year. If flattened to the thickness of a plastic bag, that is enough to cover an area of 11,000sq km (4,250sq miles). That is about the size of small countries like Qatar, Jamaica or the Bahamas.

At this rate, over the course of 50 years, plastic waste could grow to an area bigger than 550,000sq km (212,000sq miles) – about the size of France, Thailand or Ukraine.

To raise awareness about the importance of the ocean and promote its sustainable use and protection, the United Nations designated every June 8 as World Ocean Day.

(Al Jazeera)

How does plastic end up in the ocean?

Plastics are the most common form of ocean litter, comprising 80 percent of all marine pollution. Most plastics that end up in the ocean come from improper waste disposal systems that dump rubbish in rivers and streams.

Plastics in the form of fishing nets and other marine equipment are also dumped into the ocean by ships and fishing boats.

Besides plastic bags and containers, tiny particles known as microplastics also make their way into the ocean. Microplastics, which are less than 5mm (one-fifth of an inch) in length, are a major environmental concern because they can be ingested by marine life and cause harm to both animals and humans.

An estimated 50 trillion to 75 trillion pieces of microplastics are in the ocean today.

(Al Jazeera)

While research on the health effects of human consumption of microplastics is limited, some studies have indicated that microplastics can accumulate in organs such as the liver, kidneys and intestines. There are concerns that microplastic particles could potentially lead to inflammation, oxidative stress and cellular damage.

“These little particles in the ocean were breaking into little pieces and being consumed by the wildlife living there at an almost unimaginable scale. The main problem is that pieces of plastic contain toxic chemicals and these chemicals are already known to interfere with human hormones and animal hormones. They may cause the accumulation of toxins in the body that may lead to ill effects over time,” science writer and author Erica Cirino told Al Jazeera’s The Stream programme.

Which countries are the source of the most plastic in the ocean?

According to a 2021 study published by Science Advances research, 80 percent of all plastics found in the ocean comes from Asia.

The Philippines is believed to be the source of more than a third (36.4 percent) of all plastic waste in the ocean followed by India (12.9 percent), Malaysia (7.5 percent), China (7.2 percent) and Indonesia (5.8 percent).

These amounts do not include waste that is exported overseas that may be at higher risk of entering the ocean.

(Al Jazeera)

What makes plastics so dangerous for the environment?

Plastics are synthetic materials made from polymers, which are long chains of molecules. These polymers are typically derived from petroleum or natural gas.

The main problem with plastics is that they do not easily biodegrade, which means they can persist in the environment for hundreds of years, causing serious pollution problems.

Plastics that find their way into the ocean end up floating on the surface for a long time. Eventually, they sink to the bottom and get buried in the seafloor.

Plastics on the surface of the ocean represent 1 percent of the total plastics in the ocean. The other 99 percent are microplastic fragments far below the surface.

Plastic bottles, wooden planks, rusty barrels and other rubbish clog the Drina river near the eastern Bosnian town of Visegrad on May 25, 2023 [Eldar Emric/AP]

Plastics treaty draft underway, but will the most impacted countries be included?

Negotiators at last week’s global plastics treaty talks in Paris agreed to create an initial treaty draft, but full inclusion of the countries and people most impacted by plastic pollution remains uncertain.

The burdens of plastic pollution land heavily on low- and middle-income countries. High-income countries generated

87% of exported plastic waste between 1998 and 2016. Much of that exported plastic goes to developing countries including Indonesia, Vietnam and the Philippines. In these countries with limited waste management infrastructure, plastic clogs waterways, putting 218 million people at risk of devastating floods; it pollutes air with toxic fumes when burned, with waste burning causing an estimated 740,000 deaths per year; and it leaches toxic chemicals into the environment.

But it wasn’t the most impacted countries that took center stage at the negotiations. Instead, many countries that profit from fossil fuel and plastics production, including China, India, Saudi Arabia and Iran, delayed progress with procedural debates.

“It was quite evident that it was a power play,” Giulia Carlini, senior attorney at the Center for International Environmental Law, told

Environmental Health News (EHN).

These countries questioned treaty voting rules, opposing a vote by a two-thirds majority of countries in the case that all efforts to reach consensus failed. After three days, a paragraph was added to a meeting report noting the lack of agreement — effectively meaning a vote will not be possible for major treaty decisions unless all countries later agree to one. The treaty is intended to be finalized in 2024.

With other treaties, “the threat of a vote is something that we’ve seen really moving situations that before were stuck in negotiations,” said Carlini. “If there’s no possibility to vote, that will basically give veto power to a few states.”

The delays led to long nights that particularly impacted representatives of low- and middle-income countries, which often have fewer negotiators present, Arpita Bhagat, plastics policy officer at the Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives Asia Pacific, told

EHN. Accommodations near the UNESCO building where negotiations were held were expensive, so some representatives were burdened by travel time. “The meat of the negotiations were happening in the late hours,” Bhagat said.

Despite this road block, many participants were relieved when negotiations moved to substantive matters on Wednesday night. “Many countries expressed their concerns and their interest not only at the downstream, but also at the upstream,” Yuyun Ismawati, co-founder and senior advisor of the Indonesia-based Nexus3 Foundation, told

EHN.

Plastics production is on track to triple by 2060, an unsafe level for human health and the environment,

according to an international panel of scientists. Focusing only on managing plastic waste and not curbing production would fail to address plastics’ harmful lifecycle, as the treaty mandate outlines, Ismawati said.

“People are not able to see beyond plastic as a waste problem versus it being a climate problem caused by the same polluters,” said Bhagat. At the negotiations in Paris, she wore a badge that said “plastics are fossil fuels.”

Bhagat doubts that the initial treaty draft will reflect this, but she’s glad that the week ended with negotiators taking steps to reach a final global plastics treaty.

The next meeting to discuss the initial treaty draft will take place in Nairobi in November. Before then, it’s crucial for the United Nations Environment Program to organize “intersessional work” talks and training sessions that can hammer out technical details before the next meeting, said Bhagat.

Most countries agreed work is needed to determine which plastics and chemical additives are most harmful, which plastics are essential and which pathways are feasible for phasing out unnecessary plastics. Despite that, an agreement on intersessional work wasn’t reached during the week, so it’s unclear if any will take place.

If these information-building meetings do take place, Ismawati is concerned about language accessibility. Intersessional meetings are often held only in English, which can be a barrier to full access for many countries, she explained.

These discussions are most important for countries with low technical and scientific capacity to develop their knowledge on plastic pollution, said Bhagat. “There are a lot of nuances that countries want to get into in order to sufficiently advocate for their own needs for this transition to happen.”