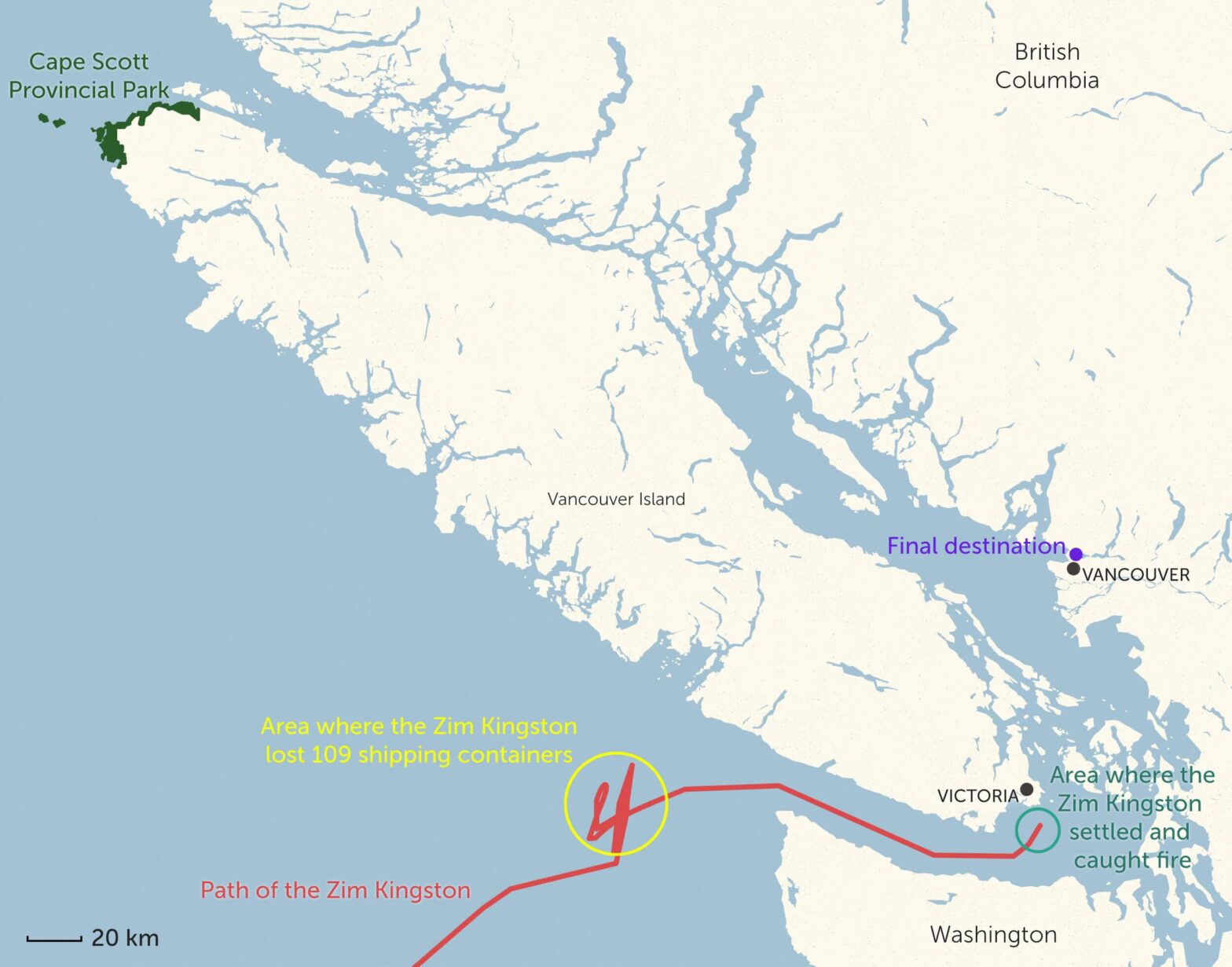

The seas off the coast of Vancouver Island were heaving on that stormy day last October, the waves five to six metres high as the wind ripped along at 35 knots. The sheltered waters of Juan de Fuca Strait, just 80 kilometres away, were worlds calmer, safer. The MV Zim Kingston, a 260-metre, Greek-owned container ship travelling from South Korea to Vancouver, could have come in. It could have done laps inside the strait as it awaited its scheduled unloading at the port in Vancouver. But no, it kept skulking along outside the strait, alone in the rain, like a hooligan stalking with a cigarette.

Why did the Zim Kingston stay out there, tracing slow laps in the water for 20 hours? The boat’s owner, Danaos Shipping, isn’t talking. Nor is Zim Integrated Shipping, which chartered the vessel. But some shipping experts are zeroing in on a hazardous chemical sitting inside a shipping container onboard. Potassium amyl xanthate, used in mining, ignites when it contacts wet air — and it makes sense to stay at sea if a substance that hot is at play on a storm-wracked ship. “If you have stuff like that loose, you’d rather deal with it out at sea,” says Willy Shih, a Harvard Business School economist who studies the shipping industry. “The last thing you want is an explosion in the harbour.”

Certainly, the Zim Kingston’s captain acted as though there was trouble on board. He contacted the Canadian Coast Guard saying it was nearing the mouth of the strait, ready to come in. Then he veered north.

A storm hit the Zim Kingston cargo ship, en route to Vancouver, before it could enter the Juan de Fuca strait. Rather than plying on to those sheltered waters it zig-zagged in the windswept open ocean, losing 109 shipping containers. It eventually made it into the strait to anchor off Victoria, where it caught fire some eight kilometres from the shore. Four of its containers eventually washed up at Cape Scott Provincial Park on the northern tip of Vancouver Island. Map: Shawn Parkinson / The Narwhal

But perhaps it’s best to read the Zim’s unexplained lurking as just another odd episode in a shipping season gone haywire. The supply chain has been thrown into chaos by the COVID-19 pandemic, with everyone stuck at home, ordering doodads off Amazon. As a result, container ships are busier than ever. The industry, which reaped US$25 billion in profits in 2020, was in the black by over US$150 billion last year. Retailers like Wal-Mart are chartering their own ships — a new twist — just to keep up with demand. Ships’ dock appointments are ever shifting now, and myriad container vessels find themselves anchored outside ports — in Long Beach, Calif. and also in Vancouver — waiting days to unload.

Mad times breed mad behaviour. And also disaster. Eventually on the Zim Kingston, storm beat ship. The deck keeled at a 35-degree angle. The Zim, capable of carrying 4,253 of the 20-foot containers (about six metres), tilted perilously, and 109 of these metal boxes slipped into the ocean.

What caused the spill? The Transportation Safety Board of Canada is still investigating, so did not offer comment, but Peter Lahay, the Canadian co-ordinator for the International Transport Workers Federation, has questions about how well the containers, often called “sea cans,” were lashed down. “Was the declared weight for those containers right, or was the load off balance?” Lahay asks. “And were labels describing the containers’ content accurate or fraudulent?”

Ships suppress a fire onboard the Zim Kingston, about eight kilometres from the shore in Victoria, on Oct. 24, 2021. The Transportation Safety Board of Canada is still investigating what went wrong on the cargo carrier, which lost 109 shipping containers in a storm outside the Juan de Fuca Strait, before the fire broke out. Photo: Chad Hipolito / The Canadian Press

What’s known is that there were 52 tonnes of xanthate on board, according to the Canadian Coast Guard. And as the Zim Kingston finally limped inside the strait to anchor off Victoria, its load was jostled and the storm was still raging. The xanthate burst into flames. Plumes of smoke rose from the deck. The Canadian and U.S. Coast Guards monitored a blaze that could not be snuffed out with water, and the lost containers floated north. When four of them washed up near the northern tip of Vancouver Island, the beach there was suddenly scattered with 71 refrigerators and a plenitude of inflatable pink plastic unicorns.

Soon, during high tides, the foam on water lapping Cape Scott Provincial Park was viscous, “like Jello,” says Ashley Tapp, a cofounder of Epic Exeo, a B.C. non-profit specializing in beach clean-up. “It was so thick with shampoo and baby lotion that my eyes and nostrils were burning.”

There are 105 more shipping containers at large, according to the Canadian Coast Guard, two of them containing the volatile xanthate, and as the seas pound at their walls and rust their latches, it’s likely that each one of them will disgorge its contents. “With every tide, every storm,” says Tapp, “more debris comes in.”

An ugly situation, certainly, but start bracing for worse. Container ships now transport about 90 per cent of all consumer products worldwide, according to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. Since 2020, the number of sea cans they’ve spilled has skyrocketed. Between 2008 and 2019, an average of 1,382 containers were lost at sea each year, according to the World Shipping Council. Last winter more than 3,000 were lost.

Meanwhile, the planet’s largest insurer of ships — Gard, of Norway — estimates that in 2020, there was one fire involving containerized cargo every two weeks. The blazes happen partly because, as they carry our lawn mowers, toothbrushes, dog toys and spatulas, container ships also transport a wide array of hazardous chemicals. “Dangerous goods” account for about 11 per cent of all boxes shipped in containerized cargo, according to Gard, and many are flammable. Calcium hypochlorite, used for bleaching paper and disinfecting swimming pools, has caused severe deck fires. In 2019, when 13 containers of that substance exploded aboard a ship called the KMTC Hong Kong as it sat in a port in Thailand, noxious smoke and acidic ashes rained on nearby villages. Over 130 people went to hospital, gasping for breath as their skin tingled and burned.

Another troubling fire came last June off the coast of Sri Lanka on a Singaporean ship called the X-Press Pearl, after nitric acid, a corrosive component in fertilizer, began leaking out of one container. It’s not clear if this compound caused the fire, but soon there were explosions on board and sea cans fell off the ship, dropping 1,524 tonnes of a strangely named menace into the Laccadive Sea.

A man fishes on a Sri Lankan beach polluted with plastic pellets or “nurdles” that washed ashore from the cargo ship MV X-Press Pearl after a fire in June 2021. Photo: Eranga Jayawardena /Associated Press

“Nurdles” are lentil-sized plastic pellets that, in molten form, can be shaped into consumer products, and they’re almost constantly trickling into the ocean. In 2016, a British consulting firm, Eunomia, estimated that over 200,000 tonnes of nurdles pollute the marine environment each year.

Fish eat nurdles, which look like their food, and humans, in turn, eat the contaminated fish. Nurdles, meanwhile, are both rafts for E. coli and cholera and sponges for toxins such as PCBs. After the X-Press Pearl spill, on some Sri Lankan beaches, the nurdles were two metres deep.

Still, Sri Lanka was in a way lucky. The X-Press Pearl is, relative to most cargo ships, tiny. It can carry just 2,756 containers. Along with the Zim Kingston, which was not known to be carrying nurdles, it’s a bit player in an industry that has been steadily supersizing its vessels for over a half-century. In 1968, when the twenty-foot container first became an industry standard, the world’s largest ship could carry 1,530 of them. Today, there are 12 ships that can accomodate 24,000 containers, and Canada has eagerly joined the jumboization party.

In 2020, the Port of Halifax completed a $38 million expansion project that, last May enabled it to welcome the biggest ship ever to enter Canada, the Marco Polo — nearly three Canadian football fields long and capable of hauling 16,022 containers. Then-Nova Scotia premier Iain Rankin was jubilant. “Big ships represent jobs and opportunities in all corners of the province,” he tweeted. “We are thrilled the Marco Polo is here.”

It is the biggest cargo ship ever to call at a Canadian port and is here because of our great infrastructure and naturally deep-water harbour. Big ships represent jobs and opportunities in all corners of the province. Welcome. We are thrilled the Marco Polo is here! pic.twitter.com/1tOyVP5ikM— Iain Rankin (@IainTRankin) May 18, 2021

But Are Solum, a senior claims executive for Gard, has grown wary watching the steady upsizing. Solum wrote in June 2020 of how, in storms, container ships often lapse into rolling where the ship pitches, or moves up and down like a teeter totter, in powerful waves, causing stacked sea cans to catapult into the ocean.

The phenomenon is the subject of numerous arcane science papers, but to Sorum the phenomenon is, at bottom, simple: on the largest vessels, sea cans are piled some 40 metres above the waterline, he notes; when the ship starts to move with the motions of the sea, “you do not have to be a physicist to understand that the container stacks will be subject to great forces.”

John Konrad, the founder of gCaptain.com, a news site that covers shipping, sees the threat of container spills in even plainer terms. “The scale of these incidents,” he says, “will surely rise.”

The spills now plaguing our oceans are due in part to climate change, which is making storms ever more volatile. But there’s also a dark power dynamic causing container ship spills to trend upwards: the industry is largely unregulated and possessed of the leverage to keep it that way.

Shipping’s governing body is a United Nations agency that the New York Times last year described as “clubby” and “secretive.” The International Maritime Organization includes 175 member states and grants a single vote to each state. If that sounds fair and reasonable, consider that the organization is the only UN agency where corporate players are allowed to represent countries.

Get The Narwhal in your inbox!People always tell us they love our newsletter. Find out yourself with a weekly dose of our ad‑free, independent journalism

According to the Times, one in four of the organization’s delegates comes from the shipping industry. Last September a climate-focused publication, DeSmog, revealed that, throughout the 2010s, the Cook Islands’ ambassador to the International Maritime Organization, Ian Finley, was paid $700,000 by a lobby group that advocates for chemical tankers — the International Parcel Tankers Association. As his cheques rolled in, Finley vociferously fought greenhouse gas emission targets for shippers. In 2016, he characterized a proposal to consider the issue as “right out of left field. To be honest,” he said, “I am staggered this was even suggested.”

The International Maritime Organization typically reaches decisions by consensus, thereby making it hard to discern each delegate’s position. Meanwhile, it forbids journalists from quoting delegates at meetings without their permission. Megan Darby, of the website Climate Home News, was suspended from meetings after she used Finley’s “left field” quote in a story.

Since 2020, the maritime organization has made efforts to reduce pollution from the sector by limiting the amount of sulphur content allowed in fuel — a move that could discourage consumption of the heavy oil produced in Canada’s oilsands region.

But in the view of many observers, the maritime organization’s climate policy remains retrograde. The shipping industry, which is not bound by the Paris Climate Accords, is still partly powered by “heavy fuel oil,” cheap, viscous stuff that’s essentially the dregs of the refining process and as thick as peanut butter when it’s cold.

The Ever Ace is the largest container ship in the world, capable of carrying nearly 24,000 shipping containers. Its slightly smaller sister ship, the Ever Given, became famous after getting stuck and blocking the Suez Canal for six days in March 2021. Photo: Kees Torn / Flickr

The shipping industry causes three per cent of all global emissions — more than all the airlines worldwide — and over the past couple decades has been fortifying its free pass to pollute via a paperwork trick. While most ships are owned by wealthy nations — European countries, the U.S., South Korea and Japan — a Marine Policy study found that, in 2019, 96 per cent of EU-owned ships were registered in less affluent countries.

While the Zim Kingston bears the flag of Malta, Comoros and Palau are currently the most popular flags of convenience. According to Shippingwatch.com, both of these tiny island nations “barely enforce environmental regulations and requirements for labour conditions for seafarers.”

Tilting against the shipping industry is not easy, but in November, in the wake of the X-Press Pearl nurdle spill, the government of Sri Lanka tried. Along with the London-based Environmental Investigation Agency and other non-governmental organizations, Sri Lanka asked the International Maritime Organization to tighten regulations controlling container ships’ transport of nurdles. The coalition implored the organization’s Marine Environment Protection Committee to recognize nurdles as “hazardous” — and thereby require them to be stored below deck in sturdy, clearly labelled packages.

The petitioners arrived at the London meeting bearing a letter signed by 50,000 supporters, but the committee spent only an hour on nurdles and took no action. To the organization’s spokesperson Natasha Brown, this was no surprise. “The document was discussed,” Brown said in an email to The Narwhal, “and the contents therein were referred on to relevant sub-committees.”

The Environmental Investigation Agency’s Deputy Ocean Campaigns leader, Christina Dixon, could only seethe. The International Maritime Organization, she said, “showed a callous disregard for plastic pollution from ships as a threat to coastal communities, ecosystems and food security. This is simply unacceptable.”

Dixon’s discontent is scant, though, when compared to the rage that now animates Gord Johns, the NDP MP for Courtenay—Alberni on Vancouver Island. In 2018, Johns tabled a motion aimed at formulating “a national strategy to combat plastic pollution in and around aquatic environments.” It passed unanimously, and as Johns sees it, in the wake of the Zim Kingston spill, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, which oversees the Coast Guard, failed to honour the resolve expressed in that unanimous vote.

After the spill, Johns says, the department’s staff “sat on their hands. They didn’t respond.” According to the province, Fisheries and Oceans did work with local and provincial authorities to control the fire on board and monitor for any environmental impacts. The department also required Danaos, the ship’s owner, to dismantle the four beached shipping containers, and roughly 30 workers spent a month clearing 47 tonnes of debris from beaches.

But Johns is outraged that the cleanup did not begin until a week after the spill and that at first the department didn’t let local environmental groups take part. He’s also livid that Danaos is largely off the hook for the 105 sea cans still missing. “It’s appalling,” he rails.

Four of the 109 shipping containers lost from the Zim Kingston washed up on the north coast of Vancouver Island. The remaining 105 have yet to be found. Photos: U.S. Coast Guard; Canadian Coast Guard; U.S. Coast Guard

With six fellow NDP MPs, all of them B.C.-based, Johns has been urging Fisheries and Oceans Minister Joyce Murray to establish what he calls an “emergency coastal debris spill response plan.” He also wants the department to hold shipping companies financially liable for all cleanup costs, even if spilled debris keeps washing up for years. Typically, shippers are, like Danaos, held accountable only for the first gush of litter.

Johns’ proposal could reorient maritime legal dynamics. Others are joining him in making similar demands. John Konrad, the gCaptain founder, argues that shipping firms should pay port fees earmarked for an ongoing cleanup fund. “We pay airport fees, don’t we?” he argues. “The only reason shippers are getting away with this is there’s no voter outrage.”

When The Narwhal called Murray’s office, her press secretary, Claire Teichman, responded that Canada’s legislators have already taken action to protect oceans. “In 2016,” she said in a written statement, “we launched the $1.5 billion Oceans Protection Plan.”

That plan aimed, among other things, to establish “24/7” emergency response to marine disasters and to “provide new boats, equipment and training that help local community members play an even more important role in marine safety.” Despite the complaints of legislators like Johns, Teichman says that Minister Murray’s initial response to the Zim Kingston spill was in full compliance with the Oceans Protection Plan. It was “thorough and effective,” she said. “The clean-up operations for all impacted beaches have been completed.” Fisheries and Oceans is not investigating the Zim Kingston spill, nor is Environment and Climate Change Canada, the department confirmed, though they are tracking the remaining containers and debris.

A responder hoses down the Zim Kingston cargo ship off Victoria’s coast after a fire broke out among its shipping containers, some of which contained dangerous chemicals used in mining. Photo: Canadian Coast Guard

In December, one of Johns’s NDP caucus allies, Lisa Marie Barron, tabled a motion that echoed his call for a more vigorous response to ocean spills, and also called for the public to be furnished with “a manifest of all missing cargo” — something not mandated under the Oceans Protection Plan. The problem with the manifest idea: containers on ships are frequently mislabelled. Indeed, in 2019, when the National Cargo Bureau, a U.S.-based marine surveying non-profit, inspected 159 dangerous-goods containers at U.S. ports, it found that 108 were inaccurately labelled. In some cases, mislabelling is simply due to human error — chemicals are complicated. But often, bald lying is involved.

In 2010, an Indian company, Research-Lab Chemical Corporation, openly acknowledged on its website that it was habitually mislabelling the very chemical that in 2019 exploded in Thailand and rained toxins onto locals. “In China,” Research-Lab wrote, “no shipping company accepts ‘Calcium Hypochlorite’ in dry container, because they believe this is dangerous chemicals for dry container. For the above reason, to ship it in dry container, we must cover the name on the B/L” — the bill of lading, or receipt. “We show another name like: calcium hydroxide, calcium Chloride ….” The calcium hypochlorite in Thailand was falsely identified. The shipping company thought that they were carrying containers filled with dolls, not a combustible chemical.

The prevalence of such misdeclarations is not well-known outside the shipping world. Barron, the member for Nanaimo—Ladysmith, was surprised when told of them, asking The Narwhal: “You mean the labels aren’t accurate?”

Alex Marland, a political scientist at Memorial University in Newfoundland and Labrador, thinks Barron’s motion is unlikely to pass. He characterizes it as a reflection of “local MPs feeling they need to do something,” and “an effort to embarrass the government into doing more.”

As the politicians posture and the analysts parse, the debris from the Zim Kingston continues to wash in. In recent weeks, Ashley Tapp, the beach cleanup specialist, has seen a swarm of disposable gray urinal mats hit the beaches of Cape Scott Provincial Park. A batch of kids’ bike helmets has washed up, too, each one emblazoned with a character from the TV cartoon Paw Patrol.

Pink plastic unicorns still litter the sand, and Cape Scott’s resident gray wolves are now eating their way through a shipment of salted prawn tips. B.C.’s Environment Ministry said the presence of junk food on the beach is the “responsible parties’ obligation,” and that BC Parks is working with the provincial and federal agencies in charge to ensure Cape Scott’s ecological values are protected.

For now, though, Tapp is most focused on an array of unusual hockey equipment that’s bringing a retro vibe to the beach. “A lot of the gear today is made out of special stuff to make it lighter,” explains the 31-year-old Tapp, once a minor league hockey manager. “The graphics are bright. But the hockey gloves washing in now are just plain-Jane, old school.” They’re from the Hansa Carrier, a ship that lost 21 containers off the coast of B.C. in 1990 and, to Tapp, they’re reminders of how long the debris dumped by the Zim Kingston will be with us.

“It could be my grandkids out there picking pink plastic unicorns up off the beach,” Tapp says. “It’s so sad because not one of the things I’ve found on the beach is essential to survival. It’s just tragic how we as humans have become dependent on all this stuff we don’t even need.”

Banner:

A fire broke out on the Zim Kingston off Victoria in October 2021 after a storm wracked the cargo carrier, loaded down with toys and dangerous chemicals alike.

Photo: Canadian Coast Guard

New titleThanks for being an avid reader of our in-depth journalism, which is read by millions and made possible thanks to more than 4,200 readers just like you.The Narwhal’s growing team is hitting the ground running in 2022 to tell stories about the natural world that go beyond doom-and-gloom headlines — and we need your support.Our model of independent, non-profit journalism means we can pour resources into doing the kind of environmental reporting you won’t find anywhere else in Canada, from investigations that hold elected officials accountable to deep dives showcasing the real people enacting real climate solutions.There’s no advertising or paywall on our website (we believe our stories should be free for all to read), which means we count on our readers to give whatever they can afford each month to keep The Narwhal’s lights on.The amazing thing? Our faith is being rewarded. We hired seven new staff over the past year and won a boatload of awards for our features, our photography and our investigative reporting. With your help, we’ll be able to do so much more in 2022.If you believe in the power of independent journalism, join our pod by becoming a Narwhal today. (P.S. Did you know we’re able to issue charitable tax receipts?)