Tesco to stop selling baby wipes that contain plastic in first for UK supermarketsRetailer is also Britain’s biggest seller of wet wipes, with customers purchasing 75m packs a year Tesco is to become the first of the main UK retailers to stop selling baby wipes containing plastic, which cause environmental damage as they block sewers and waterways after being flushed by consumers.The supermarket said it was stopping sales of branded baby wipes containing plastic from 14 March, about two years after it ceased using plastic in its own-brand products.The UK’s largest grocer is also the country’s biggest seller of baby wipes. Its customers purchase 75m packs of baby wipes every year, amounting to 4.8bn individual wipes.Tesco said it had been working to reformulate some of the other own-label and branded wipes its sells to remove plastic, including cleaning wipes and moist toilet tissue. It said its only kind of wipe that still contained plastic – designed to be used for pets – would also be plastic-free by the end of the year.Tesco began to remove plastic from its own-brand wet wipes in 2020, when it switched to biodegradable viscose, which it says breaks down far more quickly.Sarah Bradbury, Tesco’s group quality director, said: “We have worked hard to remove plastic from our wipes as we know how long they take to break down.”Tesco is not the first retailer to remove wipes from sale on environmental grounds. Health food chain Holland and Barrett said it was the first high-street retailer to ban the sale of all wet-wipe products from its 800 UK and Ireland stores in September 2019, replacing the entire range with reusable alternatives. The Body Shop beauty chain has also phased out all face wipes from its shops.It is estimated that as many as 11bn wet wipes are used in the UK each year, with the majority containing some form of plastic, many of which are flushed down the toilet, causing growing problems for the environment.Wet wipes ‘forming islands’ across UK after being flushedRead moreLast November, MPs heard how wet wipes are forming islands, causing rivers to change shape as the products pile up on their banks, while marine animals are dying after ingesting microplastics.They are also a significant component of the fatbergs that form in sewers, leading to blockages that require complex interventions to remove.Tesco said any wipes it sold that could not be flushed down the toilet were clearly labelled “do not flush”.Nevertheless, environmental campaigners and MPs have long called on retailers to do more to remove plastics from their products and packaging.The supermarket said it was trying to tackle the impact of plastic waste as part of its “4Rs” packaging strategy, which involves it removes plastic waste where possible, or reducing it, while looking at ways to reuse more and recycle.The chain said it had opened soft plastic collection points in more than 900 stores, and had launched a reusable packaging trial with shopping service Loop, which delivers food, drink and household products to consumers in refillable containers.TopicsTescoPlasticsPollutionRetail industrySupermarketsnewsReuse this content

Category Archives: Plastic Pollution Articles & News

Scientists: US needs to support a strong global agreement to curb plastic pollution

On Monday, world leaders will gather at the United Nations Environment Assembly (UNEA) in Nairobi to negotiate a global treaty to address plastic pollution. Scientists and at least 60 of the member states support a version of the treaty that could put caps on the world plastic production in addition to other policy interventions. A recent survey also found that three-quarters of 20,513 people polled from 28 countries endorse a swift phase-out of single-use plastics. The exponential rate at which global industries extract fossil fuels and produce new plastics and associated chemicals outstrips governments’ ability to regulate their safety, manage waste, and mitigate harm to people and the environment.The total mass of plastics produced exceeds both the overall mass of all land and marine animals and the planetary boundary for these novel substances, moving us out of a safe operating space for humanity. Yet industry continues to project growth, investing billions of dollars in new infrastructure and opposing national and now international efforts to curb both plastic production and pollution.

Get our FREE Plastic Action Kit

Reducing plastic pollution

Pew Charitable TrustsAs reported by Reuters, the American Chemistry Council (ACC), a powerful trade organization representing a consortium of plastics and petrochemical interests, is lobbying against production restrictions to be negotiated during the UNEA meetings, which run through March 2. The ACC’s strategy is to undermine proposed production limits on newly produced plastics by convincing politicians and regulators that plastics provide a net benefit to society and can be readily managed through long-failed downstream methods such as waste collection, recycling, and waste-to-energy conversion or yet unproven chemical or so-called ‘advanced recycling technologies’. The industry’s strategy moves against science-backed efforts to curb plastic pollution, including the recent NASEM report, requested by Congress, and the proposed Break Free From Plastic Pollution Act, which aim to address plastic’s impacts on climate, environment and health. As such, their efforts comport with the well-documented disinformation tactics deployed previously to undermine science-based environmental governance.Plastic pollution is a multifaceted problem requiring curtailment of both production and use, as proposed by Rwanda and Peru. Furthermore, the Rwanda/Peru resolution recognizes the transboundary nature of plastic pollution and the need to address it at its root. By contrast, the Japan resolution narrowly focuses on marine plastics, which, while important, is but one facet of the complex problems plastics pose.

Plastics’ harms

The proliferation of plastic debris is indeed problematic. It collects along the coastlines, clogs sewers, and causes destructive flooding in cities with insufficient waste management like Mumbai and Nairobi. Waterways stagnant with plastic and sewage are a breeding ground for disease vectors that spread cholera and malaria. Plastic waste also has negative repercussions on livelihoods. In Rwanda, Ethiopia, Mauritania, Senegal, Mali, and Niger, plastic ingestion by livestock has led to cattle death, impoverishing subsistence communities. In Ghana, where fishing supports most coastal-dwellers, water-borne plastic pollution threatens both jobs and food security.The volume of plastic debris also perpetuates existing social disparities. The export of plastic and waste from high-GDP countries in Europe and North America into the African and Asian nations since 1990has led to massive accumulation and widespread impacts. This ‘waste colonialism’ unfairly exploits environments and people in these regions. The promise of value generation through local recycling proved farcical due to the insufficient infrastructure and markets for recycled products. New plastics are cheaper than products made from recovered resin. Citizens in African nations have pushed back on the Global North’s extractive agenda, resulting in bans and restrictions on certain plastics. Re-introducing plastic under the guise of ‘improving people’s lives’ would undermine their political will, environment, health, and economies.Plastics cause harm throughout their entire lifecycle, shedding microplastic particles into our food, water, air, and soil, releasing greenhouse and toxic gases during production, landfill, and incineration. Toxic additives leach from everyday plastic products such as foodware, textiles, and car tires. Evidence for human exposure to chemicals from plastic and microplastic particles has grown exponentially in recent years. Microplastics have even been detected in human placenta. Continuous exposure to plastic chemicals disrupts development, growth, metabolism, and reproduction for organisms and humans alike. Factory emissions diminish air and water quality, violating the health and human rights of the predominantly low-income communities and communities of color who live along the fenceline. And without reduction mandates, plastics’ CO2 emissions will amount to 6.5 gigatons by 2050 eating 10–13% of the remaining CO2 budget, accelerating global heating. While the Rwanda/Peru resolution reaffirms the importance of addressing plastics toxic and climate implications, such provisions were specifically erased in the Japan resolution.

UN plastics treaty

UN Environmental Program, via TwitterScientific evidence highlights the need for unanimouspolitical support for an ambitious global treaty regulating plastics during their entire lifecycle to account for their impacts to climate, humans, and ecosystems. Such a treaty will need to include caps on production of new plastic to prevent further irreversible global damage. The Rwanda/Peru resolution includes language to address plastics’ impacts from extraction of raw materials to production and end-of-life. It goes beyond dealing with plastic as a waste problem and considers systemic solutions to reduce, replace, reuse, and recycle plastic effectively. Voluntary, optional or market-led solutions will not suffice to solve this complex, global problem. To truly address the impacts of plastics on the environment, society and health, in line with the UN Sustainable Development Goals and call for nations to protect clean and healthy environments as a human right, the resolutions must be binding. Voluntary, optional or market-led solutions will not solve these wicked problems. There is no time for lengthy negotiations aimed at delaying and diluting urgently needed action.

Co-authors

The authors thank five expert colleagues for their help in the preparation of this OP-ed: Dr. Rebecca AltmanDr. Susanne BranderDr. Tridibesh DeyAnja KriegerDr. Tony R. Walker

About the authors

Prof. Bethanie Carney Almroth is an ecotoxicologist at the University of Gothenburg. She researches the effects of chemicals and plastics in marine and freshwater animals, and works to find means for sustainable development, She also coordinates the Gesamp working group on plastics, providing scientific advice to UN organizations. @BCarneyAlmroth, email: bethanie.carney@bioenv.gu.seDr. Melanie Bergmann is a polar marine biologist at the Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research who has researched and published on plastic pollution since 2012. She edited the textbook Marine Anthropogenic Litter and runs the online portal Litterbase as well as a pollution observatory in the Arctic. She is part of the AMAP Expert Group on Microplastics and Litter providing scientific advice to the Arctic Council. @MelanieBergma18, email: Melanie.Bergmann@awi.deDr. Scott Coffin is a research scientist at the California State Water Resources Control Board, who has researched plastic pollution since 2014. He leads California’s efforts to monitor and manage microplastics pollution in drinking water and the environment. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any government agency or institution. @DrSCoffin, email: scott.l.coffin@gmail.comDr. Rebecca Altman is a Providence-based writer and independent scholar working on an intimate history of plastics for Scribner Books (US) and Oneworld (UK). Recent work has appeared in The Atlantic, Science, Aeon and Orion. She holds a Ph.D. in environmental sociology from Brown University. Dr. Susanne Brander is a professor and ecotoxicologist at Oregon State University, co-lead of the Pacific Northwest Consortium on Plastics, and recent co-chair of a California Ocean Science Trust advisory team on marine microplastics. Her primary focus is on the effects of stressors such as emerging pollutants, including micro and nanoplastics, on aquatic organisms; and her research and teaching span both ecological and human health impacts. Anja Krieger is a writer and podcaster from Germany working in science communication. She’s reported as a freelance journalist for over a decade in media outlets such as Ensia, Undark, Vox News, PRI The World, Deutschlandradio, and Die Zeit. Anja is the creator of the Plastisphere podcast and co-producer of Life in the Soil. A cultural scientist by training, she’s completed the Knight Science Journalism Fellowship Program at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Dr. Tridibesh Dey is a South Asian anthropologist generating theoretical knowledge about plastics from long-term engaged fieldwork with communities and landscapes most affected by these materials. Having trained originally in the natural sciences with professional experiences in sustainable development, Dr. Dey offers practice-oriented multi-disciplinary perspectives on the complex social entanglements of the material one might call ‘plastic’. Dr. Tony Walker is an Associate Professor at Dalhousie University. He has studied impacts of plastic pollution for nearly 30 years and was invited by the Deputy Minister of Environment and Climate Change Canada to to help develop the Ocean Plastics Charter for Canada’s 2018 G7 presidency. He participated in the Canadian Science Symposium on Plastics to inform Canada’s Plastic Science Agenda, and represented Canada at the G7 Science Meeting on Plastic Pollution in Paris, France in 2019.The views expressed in this piece do not necessarily reflect those of Environmental Health News or The Daily Climate.Banner photo of plastic garbage next to the sea by Antoine Giret/UnsplashFrom Your Site ArticlesRelated Articles Around the Web

Africa faces tough job not to become world's plastic 'dustbin'

Africa faces tough job not to become world’s plastic ‘dustbin’ – Daily Times We use cookies to ensure that we give you the best experience on our website. If you continue to use this site we will assume that you are happy with it.OkPrivacy policy

Plastic pollution is a global problem – here's how to design an effective treaty to curb it

Plastic pollution is accumulating worldwide, on land and in the oceans. According to one widely cited estimate, by 2025, 100 million to 250 million metric tons of plastic waste could enter the ocean each year. Another study commissioned by the World Economic Forum projects that without changes to current practices, there may be more plastic by weight than fish in the ocean by 2050.

On March 2, 2022, representatives from 175 nations around the world took a historic step toward ending that pollution. The United Nations Environment Assembly voted to task a committee with forging a legally binding global treaty on plastic pollution by 2024. U.N. Environment Program Executive Director Inger Andersen described it as “an insurance policy for this generation and future ones, so they may live with plastic and not be doomed by it.”

I am a legal scholar and have studied questions related to food, animal welfare and environmental law. My forthcoming book, “Our Plastic Problem and How to Solve It,” explores legislation and policies to address this global “wicked problem.”

I believe plastic pollution requires a local, national and global response. While acting together on a world scale will be challenging, lessons from some other environmental treaties suggest features that can improve an agreement’s chances of success.

A pervasive problem

Scientists have discovered plastic in some of the most remote parts of the globe, from polar ice to Texas-sized gyres in the middle of the ocean. Plastic can enter the environment from a myriad of sources, ranging from laundry wastewater to illegal dumping, waste incineration and accidental spills.

Plastic never completely degrades. Instead, it breaks down into tiny particles and fibers that are easily ingested by fish, birds and land animals. Larger plastic pieces can transport invasive species and accumulate in freshwater and coastal environments, altering ecosystem functions.

A 2021 report by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine on ocean plastic pollution concluded that “[w]ithout modifications to current practices … plastics will continue to accumulate in the environment, particularly the ocean, with adverse consequences for ecosystems and society.”

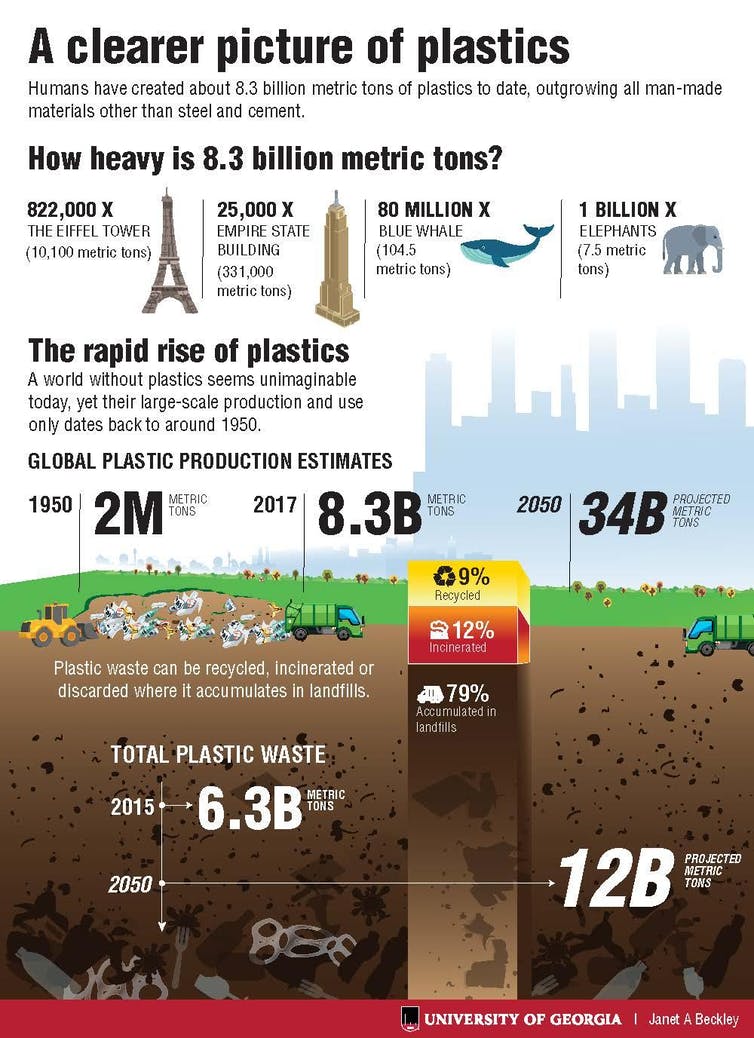

Plastic pollution by the numbers.

University of Georgia, CC BY-ND

National policies are not enough

To address this problem, the U.S. has focused on waste management and recycling rather than regulating plastic producers and businesses that use plastic in their products. Failing to address the sources means that policies have limited impact. That’s especially true since the U.S. generates 37.5 million tons of plastic yearly, but only recycles about 9% of it.

Some countries, such as France and Kenya, have banned single-use plastics. Others, like Germany, have mandated plastic bottle deposit schemes. Canada has classified manufactured plastic items as toxic, which gives its national government broad power to regulate them.

In my view, however, these efforts too will fall short if countries producing and using the most plastic do not adopt policies across its life cycle.

Growing consensus

Plastic pollution crosses boundaries, so countries need to work together to curb it. But existing treaties such as the 1989 Basel Convention, which governs international shipment of hazardous wastes, and the 1982 U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea offer little leverage, for several reasons.

First, these treaties were not designed specifically to address plastic. Second, the largest plastic polluters – notably, the U.S. – have not joined these agreements. Alternative international approaches such as the Ocean Plastics Charter, which encourages governments and global and regional businesses to design plastic products for reuse and recycling, are voluntary and nonbinding.

Fortunately, many world and business leaders now support a uniform, standardized and coordinated global approach to managing and eliminating plastic waste in the form of a treaty.

The American Chemistry Council, an industry trade group, supports an agreement that will accelerate a transition to a more circular economy that promotes waste reduction and reuse by focusing on waste collection, product design and recycling technology. America’s Plastic Makers and the International Council of Chemical Associations have also made public statements supporting a global agreement to establish “a targeted goal to ensure access to proper waste management and eliminate leakage of plastic into the ocean.”

However, these organizations maintain that plastic products can help reduce energy use and greenhouse gas emissions – for example, by enabling automakers to build lighter cars – and are likely to oppose an agreement that limits plastic production. As I see it, this makes leadership and action by governments critical.

The Biden administration also has stated its support for a treaty and is sending Secretary of State Antony Blinken to the Nairobi meeting. On Feb. 11, 2022, the White House released a joint statement with France that expressed support for negotiating “a global agreement to address the full life cycle of plastics and promote a circular economy.”

Early treaty drafts outline two competing approaches. One seeks to reduce plastic throughout its life cycle, from production to disposal, a strategy that would probably include methods such as banning or phasing out single-use plastic products.

A contrasting approach focuses on eliminating plastic waste through innovation and design – for example, by spending more on waste collection, recycling and development of environmentally benign plastics.

Some harmful impacts of plastic waste become more intense as the plastic breaks down into smaller and smaller fragments.

Elements of an effective treaty

Countries have come together to solve environmental problems before. The global community has successfully addressed acid rain, stratospheric ozone depletion and mercury contamination through international treaties. These agreements, which include the U.S., offer strategies for a plastics treaty.

The Montreal Protocol, for example, required countries to report their production and consumption of ozone-depleting substances so that countries could hold each other accountable. As part of the Convention on Long-range Air Pollution, countries agreed to reduce sulfur dioxide emissions, but were allowed to select the method that worked best for them. For the U.S., that involved a system of buying and selling emission allowances that became part of the Clean Air Act Amendments of 1990.

Based on these precedents, I see plastic as a good candidate for an international treaty. Like ozone, sulfur and mercury, plastic comes from specific, identifiable human activities that occur across the globe. Many countries contribute, so the problem is transboundary in nature.

In addition to providing a framework for keeping plastic out of the ocean, I believe a plastic pollution treaty should include reduction targets for both producing less plastic and generating less waste that are specific, measurable and achievable. The treaty should be binding but flexible, allowing countries to meet these targets as they choose.

In my view, negotiations should consider the interests of those who experience the disproportionate impacts of plastic, as well as those who make a living off recycling waste as part of the informal economy. Finally, an international treaty should promote collaboration and sharing of data, resources and best practices.

Since plastic pollution doesn’t stay in one place, all nations will benefit from finding ways to curb it.

This article was updated March 2, 2022, with the international vote to write a plastics treaty.

[Over 140,000 readers rely on The Conversation’s newsletters to understand the world. Sign up today.]

Sarah J. Morath: Plastic pollution is a global problem – here's how to design an effective treaty to curb it

Plastic pollution is accumulating worldwide, on land and in the oceans. According to one widely cited estimate, by 2025, 100 million to 250 million metric tons of plastic waste could enter the ocean each year. Another study commissioned by the World Economic Forum projects that without changes to current practices, there may be more plastic by weight than fish in the ocean by 2050.

On Feb. 28, 2022, a meeting of the United Nations Environment Assembly will open in Nairobi, Kenya. At that meeting, representatives from 193 countries are expected to consider a resolution that would launch negotiations on a legally binding global treaty to reduce plastic pollution. “[N]o country can adequately address the various aspects of this challenge alone,” the draft resolution states.

I am a legal scholar and have studied questions related to food, animal welfare and environmental law. My forthcoming book, “Our Plastic Problem and How to Solve It,” explores legislation and policies to address this global “wicked problem.”

I believe plastic pollution requires a local, national and global response. While acting together on a world scale will be challenging, lessons from some other environmental treaties suggest features that can improve an agreement’s chances of success.

A pervasive problem

Scientists have discovered plastic in some of the most remote parts of the globe, from polar ice to Texas-sized gyres in the middle of the ocean. Plastic can enter the environment from a myriad of sources, ranging from laundry wastewater to illegal dumping, waste incineration and accidental spills.

Plastic never completely degrades. Instead, it breaks down into tiny particles and fibers that are easily ingested by fish, birds and land animals. Larger plastic pieces can transport invasive species and accumulate in freshwater and coastal environments, altering ecosystem functions.

A 2021 report by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine on ocean plastic pollution concluded that “[w]ithout modifications to current practices … plastics will continue to accumulate in the environment, particularly the ocean, with adverse consequences for ecosystems and society.”

Plastic pollution by the numbers.

University of Georgia, CC BY-ND

National policies are not enough

To address this problem, the U.S. has focused on waste management and recycling rather than regulating plastic producers and businesses that use plastic in their products. Failing to address the sources means that policies have limited impact. That’s especially true since the U.S. generates 37.5 million tons of plastic yearly, but only recycles about 9% of it.

Some countries, such as France and Kenya, have banned single-use plastics. Others, like Germany, have mandated plastic bottle deposit schemes. Canada has classified manufactured plastic items as toxic, which gives its national government broad power to regulate them.

In my view, however, these efforts too will fall short if countries producing and using the most plastic do not adopt policies across its life cycle.

Growing consensus

Plastic pollution crosses boundaries, so countries need to work together to curb it. But existing treaties such as the 1989 Basel Convention, which governs international shipment of hazardous wastes, and the 1982 U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea offer little leverage, for several reasons.

First, these treaties were not designed specifically to address plastic. Second, the largest plastic polluters – notably, the U.S. – have not joined these agreements. Alternative international approaches such as the Ocean Plastics Charter, which encourages governments and global and regional businesses to design plastic products for reuse and recycling, are voluntary and nonbinding.

Fortunately, many world and business leaders now support a uniform, standardized and coordinated global approach to managing and eliminating plastic waste in the form of a treaty.

The American Chemistry Council, an industry trade group, supports an agreement that will accelerate a transition to a more circular economy that promotes waste reduction and reuse by focusing on waste collection, product design and recycling technology. America’s Plastic Makers and the International Council of Chemical Associations have also made public statements supporting a global agreement to establish “a targeted goal to ensure access to proper waste management and eliminate leakage of plastic into the ocean.”

However, these organizations maintain that plastic products can help reduce energy use and greenhouse gas emissions – for example, by enabling automakers to build lighter cars – and are likely to oppose an agreement that limits plastic production. As I see it, this makes leadership and action by governments critical.

The Biden administration also has stated its support for a treaty and is sending Secretary of State Antony Blinken to the Nairobi meeting. On Feb. 11, 2022, the White House released a joint statement with France that expressed support for negotiating “a global agreement to address the full life cycle of plastics and promote a circular economy.”

Early treaty drafts outline two competing approaches. One seeks to reduce plastic throughout its life cycle, from production to disposal, a strategy that would probably include methods such as banning or phasing out single-use plastic products.

A contrasting approach focuses on eliminating plastic waste through innovation and design – for example, by spending more on waste collection, recycling and development of environmentally benign plastics.

Some harmful impacts of plastic waste become more intense as the plastic breaks down into smaller and smaller fragments.

Elements of an effective treaty

Countries have come together to solve environmental problems before. The global community has successfully addressed acid rain, stratospheric ozone depletion and mercury contamination through international treaties. These agreements, which include the U.S., offer strategies for a plastics treaty.

The Montreal Protocol, for example, required countries to report their production and consumption of ozone-depleting substances so that countries could hold each other accountable. As part of the Convention on Long-range Air Pollution, countries agreed to reduce sulfur dioxide emissions, but were allowed to select the method that worked best for them. For the U.S., that involved a system of buying and selling emission allowances that became part of the Clean Air Act Amendments of 1990.

Based on these precedents, I see plastic as a good candidate for an international treaty. Like ozone, sulfur and mercury, plastic comes from specific, identifiable human activities that occur across the globe. Many countries contribute, so the problem is transboundary in nature.

In addition to providing a framework for keeping plastic out of the ocean, I believe a plastic pollution treaty should include reduction targets for both producing less plastic and generating less waste that are specific, measurable and achievable. The treaty should be binding but flexible, allowing countries to meet these targets as they choose.

In my view, negotiations should consider the interests of those who experience the disproportionate impacts of plastic, as well as those who make a living off recycling waste as part of the informal economy. Finally, an international treaty should promote collaboration and sharing of data, resources and best practices.

Since plastic pollution doesn’t stay in one place, all nations will benefit from finding ways to curb it.

[Over 140,000 readers rely on The Conversation’s newsletters to understand the world. Sign up today.]

California officials approve plan to crack down on microplastics polluting the ocean

California aims to sharply limit the spiraling scourge of microplastics in the ocean, while urging more study of this threat to fish, marine mammals and potentially to humans, under a plan a state panel approved Wednesday.The Ocean Protection Council voted to make California the first state to adopt a comprehensive plan to rein in the pollution, recommending everything from banning plastic-laden cigarette filters and polystyrene drinking cups to the construction of more green zones to filter plastics from stormwater before it spills into the sea.The proposals in the report are only advisory, with approval from other agencies and the Legislature required to put many of the reforms into place. But the signaling of resolve from council members – including Controller Betty Yee and the heads of the Natural Resources and Environmental Protection agencies – puts California in the vanguard of a worldwide push on the issue.“What this action says is that we have to deal immediately with what has become a global environmental catastrophe,” said Mark Gold, executive director of the Ocean Protection Council. “We are moving ahead, while we continue to learn more about the science.”California Natural Resources Secretary Wade Crowfoot added: “By reducing pollution at its source, we safeguard the health of our rivers, wetlands and oceans, and protect all of the people and nature that depends on these waters.”Industry opposition has helped kill legislation that would force single-use packaging to be recyclable or compostable. But voters will have a chance in November to impose those requirements with the California Recycling and Plastic Pollution Reduction Voter Act. The ballot measure would force single-use plastics to be reusable, recyclable or compostable, with the goal of cutting plastic waste by one-fourth by 2030. The measure would charge up to one cent per item to provide incentive to reduce waste, with the funds going to recycling and cleanup measures.Scientists have estimated that 11 million metric tons of plastic spills into the ocean each year, an amount that could triple by 2040 without a course correction, the state’s report says.Microplastics are commonly defined as particles smaller than 5 millimeters (about 3/16 of an inch) in diameter. Some come from the breakdown of plastic bags, bottles and wraps, others are derived from clothing fibers, fishing gear and containers.A 2019 study of San Francisco Bay surprised some scientists when it concluded that the single largest source of microplastics was the tiny particles from vehicle tires that washed from streets into the bay.The often invisible pollution has been found not only in the most remote oceans, but in seemingly pristine mountain streams, in farmland worldwide and “within human placentas, stool samples and lung tissue,” the state’s report noted. Climate & Environment The biggest likely source of microplastics in California coastal waters? Our car tires Driving is not just an air pollution and climate change problem. Turns out, rubber particles from car tires might be the largest contributor of microplastics in California coastal waters, according to the most comprehensive study to date. A wide variety of chemicals in the microplastics have been shown to harm fish and other sea creatures — inflaming tissue, stunting growth and harming reproduction.The state’s plan outlined 22 actions to stem the problem, some designed to eliminate plastic waste at the source, others to cut off the waste before it gets into the air, storm drains and sewers and still others meant to enlighten the public about the problem.Some of the proposals attack highly visible segments of the waste stream.For years, environmental groups have routinely found microplastic-laden cigarette butts to be the most common form of trash in beach cleanups. The ocean protection agency suggested that California move this year to prohibit the sale and distribution of cigarette filters, electronic cigarettes, plastic cigar tips, and unrecyclable tobacco product packaging.Similarly, the group recommended a ban on foodware and packaging made of polystyrene, which includes Styrofoam. It sets 2023 as a target date for that restriction.The officials also recommended that state agencies use their own purchasing power to acquire reusable foodware whenever possible and to cut reliance on single-use utensils.Other changes, already adopted, need to be put into place, like a 2021 law that requires restaurants to provide single-use utensils and condiments only when customers ask for them.The state would also like to see manufacturers produce washing machines that filter out microfibers before they end up in storm drains. They would like vehicle tire makers to find alternatives that put less micro-waste on roadways. It’s unclear whether those changes will be mandated, or merely encouraged.For plastics that are not reduced at the source, the ocean group recommended a number of measures to restrict the flow of microplastics into storm drains, streams and into the ocean. Those solutions sometimes come under the heading of “low-impact development” and include creation of trenches, greenways and “rain gardens” that filter and hold waste before it flows out to sea. One woman’s crusade: a clean patch of beach One woman’s crusade: a clean patch of beach It also recommended placing more trash cans along beaches and other “hot spots,” where plastics can readily find their way into waterways.While research about microplastic pollution has increased, there has not been a systematic approach or agreement on what pollutants should be measured. The ocean agency’s plan outlines shortcomings in the science that need to be corrected, so that pollution measures can be standardized and safety thresholds created.Microplastic pollution has drawn international attention. The United Nations is attempting to draft a treaty to rein in the contaminants, while the European Union is drawing up a policy of its own.The U.S. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine reported last year that America produced more plastic pollution, through 2016, than any other country, exceeding all the European Union nations combined.The California’s ocean agency’s action this week grew out of a 2018 law, authored by Sen. Anthony Portantino (D-La Canada Flintridge), that demanded state action.Officials at the state Water Resources Control Board are working on a separate policy to measure and set safety guidelines for the levels of microplastics that will be permissible in drinking water.The San Francisco Bay pollution study, co-authored by the San Francisco Estuary Institute, found that more than 7 trillion bits of plastic washed into the bay each year.Warner Chabot, executive director of the institute, praised state leaders for approving the microplastics plan.“Solving the problem requires that we stop or greatly reduce microplastics at their source,” Chabot said. “There is no quick fix and a range of options for a solution.”

California officials approve plan to crack down on microplastics polluting the ocean

California aims to sharply limit the spiraling scourge of microplastics in the ocean, while urging more study of this threat to fish, marine mammals and potentially to humans, under a plan a state panel approved Wednesday.The Ocean Protection Council voted to make California the first state to adopt a comprehensive plan to rein in the pollution, recommending everything from banning plastic-laden cigarette filters and polystyrene drinking cups to the construction of more green zones to filter plastics from stormwater before it spills into the sea.The proposals in the report are only advisory, with approval from other agencies and the Legislature required to put many of the reforms into place. But the signaling of resolve from council members – including Controller Betty Yee and the heads of the Natural Resources and Environmental Protection agencies – puts California in the vanguard of a worldwide push on the issue.“What this action says is that we have to deal immediately with what has become a global environmental catastrophe,” said Mark Gold, executive director of the Ocean Protection Council. “We are moving ahead, while we continue to learn more about the science.”California Natural Resources Secretary Wade Crowfoot added: “By reducing pollution at its source, we safeguard the health of our rivers, wetlands and oceans, and protect all of the people and nature that depends on these waters.”Industry opposition has helped kill legislation that would force single-use packaging to be recyclable or compostable. But voters will have a chance in November to impose those requirements with the California Recycling and Plastic Pollution Reduction Voter Act. The ballot measure would force single-use plastics to be reusable, recyclable or compostable, with the goal of cutting plastic waste by one-fourth by 2030. The measure would charge up to one cent per item to provide incentive to reduce waste, with the funds going to recycling and cleanup measures.Scientists have estimated that 11 million metric tons of plastic spills into the ocean each year, an amount that could triple by 2040 without a course correction, the state’s report says.Microplastics are commonly defined as particles smaller than 5 millimeters (about 3/16 of an inch) in diameter. Some come from the breakdown of plastic bags, bottles and wraps, others are derived from clothing fibers, fishing gear and containers.A 2019 study of San Francisco Bay surprised some scientists when it concluded that the single largest source of microplastics was the tiny particles from vehicle tires that washed from streets into the bay.The often invisible pollution has been found not only in the most remote oceans, but in seemingly pristine mountain streams, in farmland worldwide and “within human placentas, stool samples and lung tissue,” the state’s report noted. Climate & Environment The biggest likely source of microplastics in California coastal waters? Our car tires Driving is not just an air pollution and climate change problem. Turns out, rubber particles from car tires might be the largest contributor of microplastics in California coastal waters, according to the most comprehensive study to date. A wide variety of chemicals in the microplastics have been shown to harm fish and other sea creatures — inflaming tissue, stunting growth and harming reproduction.The state’s plan outlined 22 actions to stem the problem, some designed to eliminate plastic waste at the source, others to cut off the waste before it gets into the air, storm drains and sewers and still others meant to enlighten the public about the problem.Some of the proposals attack highly visible segments of the waste stream.For years, environmental groups have routinely found microplastic-laden cigarette butts to be the most common form of trash in beach cleanups. The ocean protection agency suggested that California move this year to prohibit the sale and distribution of cigarette filters, electronic cigarettes, plastic cigar tips, and unrecyclable tobacco product packaging.Similarly, the group recommended a ban on foodware and packaging made of polystyrene, which includes Styrofoam. It sets 2023 as a target date for that restriction.The officials also recommended that state agencies use their own purchasing power to acquire reusable foodware whenever possible and to cut reliance on single-use utensils.Other changes, already adopted, need to be put into place, like a 2021 law that requires restaurants to provide single-use utensils and condiments only when customers ask for them.The state would also like to see manufacturers produce washing machines that filter out microfibers before they end up in storm drains. They would like vehicle tire makers to find alternatives that put less micro-waste on roadways. It’s unclear whether those changes will be mandated, or merely encouraged.For plastics that are not reduced at the source, the ocean group recommended a number of measures to restrict the flow of microplastics into storm drains, streams and into the ocean. Those solutions sometimes come under the heading of “low-impact development” and include creation of trenches, greenways and “rain gardens” that filter and hold waste before it flows out to sea. One woman’s crusade: a clean patch of beach One woman’s crusade: a clean patch of beach It also recommended placing more trash cans along beaches and other “hot spots,” where plastics can readily find their way into waterways.While research about microplastic pollution has increased, there has not been a systematic approach or agreement on what pollutants should be measured. The ocean agency’s plan outlines shortcomings in the science that need to be corrected, so that pollution measures can be standardized and safety thresholds created.Microplastic pollution has drawn international attention. The United Nations is attempting to draft a treaty to rein in the contaminants, while the European Union is drawing up a policy of its own.The U.S. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine reported last year that America produced more plastic pollution, through 2016, than any other country, exceeding all the European Union nations combined.The California’s ocean agency’s action this week grew out of a 2018 law, authored by Sen. Anthony Portantino (D-La Canada Flintridge), that demanded state action.Officials at the state Water Resources Control Board are working on a separate policy to measure and set safety guidelines for the levels of microplastics that will be permissible in drinking water.The San Francisco Bay pollution study, co-authored by the San Francisco Estuary Institute, found that more than 7 trillion bits of plastic washed into the bay each year.Warner Chabot, executive director of the institute, praised state leaders for approving the microplastics plan.“Solving the problem requires that we stop or greatly reduce microplastics at their source,” Chabot said. “There is no quick fix and a range of options for a solution.”

World must 'restrain demand' for plastic, OECD report says

Despite growing recognition that the world is making more plastic than it can handle, the petrochemical industry has kept churning out plastic products — to the detriment of the planet and the climate.

A report released on Tuesday by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, or OECD, offers a granular look at plastics’ life cycle, describing a system that dumps millions of tons of plastic waste into the environment every year. In 2019, before the COVID-19 pandemic began, the report found that only 9 percent of the world’s 353 million tons of plastic waste was recycled into new products. The rest was either burned, put in landfills, or “mismanaged” — dumped in uncontrolled sites, burned in open pits, or leaked into the environment.

The authors of the OECD’s first report on the world’s plastics called for countries to take urgent action to rein in the problem, including by scaling back demand for single-use plastics. “[T]he current linear model of mass plastics production, consumption, and disposal is unsustainable,” the report says.

The analysis comes just days ahead of a high-stakes United Nations summit, where world leaders are expected to begin drafting a global treaty on plastic pollution. The talks are backed by many of the world’s leading plastic producers, and advocates are hopeful that they will yield a binding agreement to address plastic’s full life cycle and restrain its production. Such an agreement would represent a major departure from the post-productions efforts — ocean cleanup initiatives, for example — that have for decades defined most plastic management strategies.

Part of the reason these approaches haven’t worked is because they are ill-equipped to keep up with the sheer amount of plastic the world produces. According to the OECD report, global plastic production has skyrocketed in the past two decades, outpacing economic growth by nearly 40 percent. By 2019, plastic production had doubled since 2000 and reached an eye-watering 460 million metric tons — about the same weight as 45,500 Eiffel Towers. This growth appears to be unstoppable; not even the Great Recession nor the COVID-19 pandemic managed to curb plastics use for long. In 2020, when the coronavirus first began shuttering economies and disrupting global supply chains, the use of plastic dipped a mere 2.2 percent below 2019 levels. The OECD says it is now “likely to rebound once again.”

Some of the top companies contributing to the planet’s glut of plastic are better known as oil and gas producers: ExxonMobil, Sinopec, Saudi Aramco. Anticipating a global shift to cleaner forms of energy, these firms have invested big in plastics that can be sold — and discarded — abroad.

Herons walk amid plastic waste at a Panama City beach.

Luis Acosta / AFP via Getty Images

These companies’ plans could inundate poorer parts of the world with plastic. They could also help raise global temperatures. In 2019, the report concluded, plastics generated 3.4 percent of the planet’s greenhouse gas emissions — mostly due to carbon-intensive processes needed to manufacture plastic from fossil fuels. This finding echoes previous work from the U.S.-based advocacy group Beyond Plastics, which, in a study published last October, called plastic “the new coal.” That study used federal data to suggest that the American plastics industry is on track to overtake coal in its contribution to climate change by 2030.

Beyond Plastics and other environmental advocates have long contended that this monumental scale of production is almost certainly unnecessary. According to the OECD’s analysis, 40 percent of the world’s plastic production in 2019 went toward packaging with an average useful lifetime of less than six months. Then, even if that plastic makes it into a controlled landfill — what many activists say is the least bad way to dispose of plastic waste — it can take hundreds of years to degrade. Other disposal methods like incineration emit toxic chemicals into the atmosphere. And so-called “leakage,” the release of plastics into waterways and ecosystems, can strangle wildlife and poison the food chain.

What can be done? The OECD recommended four key areas for intervention, including bolstering markets for recycled products and investing in “innovation” to extend the lifetimes of plastic goods. The organization also stressed the need for domestic policies to “restrain demand” for plastics, saying that “current bans and taxes are insufficient.” The organization recommended a suite of ideas that could make it more expensive for companies to churn out plastics: Fees could force companies to assume the costs of waste management and collection; governments could take away fossil fuel subsidies.

In response to Grist’s request for comment, Joshua Baca, vice president of plastics for the trade group the American Chemistry Council, said that plastic companies already supported many of the OECD’s recommendations, including recycled content standards and “improving access to waste collection.”

Carroll Muffett, president and CEO of the advocacy group Center for International Environmental Law, said that many of the OECD’s recommendations were well-intentioned, but wished the report had placed a greater emphasis on limiting plastic production. Characterizing plastic pollution as a mismanaged waste problem, he said, can distract decision-makers from policies designed to create less waste in the first place.

This is the point that hundreds of advocacy groups and scientists have been making in the lead-up to this month’s U.N. Environment Assembly meeting in Nairobi, Kenya. In December, more than 700 civil society groups, workers and trade unions, Indigenous peoples, women’s and youth groups, and others urged U.N. member states to craft a legally binding agreement that includes strategies to wind down global plastic production. Roughly 90 companies and more than 2 million individuals have made similar appeals.

“If you only focus on the demand side of the equation without addressing the expansion of that production capacity,” Muffett said, “then you are always chasing the problem and never catching it.”

World must 'restrain demand' for plastic, OECD report says

Despite growing recognition that the world is making more plastic than it can handle, the petrochemical industry has kept churning out plastic products — to the detriment of the planet and the climate.

A report released on Tuesday by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, or OECD, offers a granular look at plastics’ life cycle, describing a system that dumps millions of tons of plastic waste into the environment every year. In 2019, before the COVID-19 pandemic began, the report found that only 9 percent of the world’s 353 million tons of plastic waste was recycled into new products. The rest was either burned, put in landfills, or “mismanaged” — dumped in uncontrolled sites, burned in open pits, or leaked into the environment.

The authors of the OECD’s first report on the world’s plastics called for countries to take urgent action to rein in the problem, including by scaling back demand for single-use plastics. “[T]he current linear model of mass plastics production, consumption, and disposal is unsustainable,” the report says.

The analysis comes just days ahead of a high-stakes United Nations summit, where world leaders are expected to begin drafting a global treaty on plastic pollution. The talks are backed by many of the world’s leading plastic producers, and advocates are hopeful that they will yield a binding agreement to address plastic’s full life cycle and restrain its production. Such an agreement would represent a major departure from the post-productions efforts — ocean cleanup initiatives, for example — that have for decades defined most plastic management strategies.

Part of the reason these approaches haven’t worked is because they are ill-equipped to keep up with the sheer amount of plastic the world produces. According to the OECD report, global plastic production has skyrocketed in the past two decades, outpacing economic growth by nearly 40 percent. By 2019, plastic production had doubled since 2000 and reached an eye-watering 460 million metric tons — about the same weight as 45,500 Eiffel Towers. This growth appears to be unstoppable; not even the Great Recession nor the COVID-19 pandemic managed to curb plastics use for long. In 2020, when the coronavirus first began shuttering economies and disrupting global supply chains, the use of plastic dipped a mere 2.2 percent below 2019 levels. The OECD says it is now “likely to rebound once again.”

Some of the top companies contributing to the planet’s glut of plastic are better known as oil and gas producers: ExxonMobil, Sinopec, Saudi Aramco. Anticipating a global shift to cleaner forms of energy, these firms have invested big in plastics that can be sold — and discarded — abroad.

Herons walk amid plastic waste at a Panama City beach.

Luis Acosta / AFP via Getty Images

These companies’ plans could inundate poorer parts of the world with plastic. They could also help raise global temperatures. In 2019, the report concluded, plastics generated 3.4 percent of the planet’s greenhouse gas emissions — mostly due to carbon-intensive processes needed to manufacture plastic from fossil fuels. This finding echoes previous work from the U.S.-based advocacy group Beyond Plastics, which, in a study published last October, called plastic “the new coal.” That study used federal data to suggest that the American plastics industry is on track to overtake coal in its contribution to climate change by 2030.

Beyond Plastics and other environmental advocates have long contended that this monumental scale of production is almost certainly unnecessary. According to the OECD’s analysis, 40 percent of the world’s plastic production in 2019 went toward packaging with an average useful lifetime of less than six months. Then, even if that plastic makes it into a controlled landfill — what many activists say is the least bad way to dispose of plastic waste — it can take hundreds of years to degrade. Other disposal methods like incineration emit toxic chemicals into the atmosphere. And so-called “leakage,” the release of plastics into waterways and ecosystems, can strangle wildlife and poison the food chain.

What can be done? The OECD recommended four key areas for intervention, including bolstering markets for recycled products and investing in “innovation” to extend the lifetimes of plastic goods. The organization also stressed the need for domestic policies to “restrain demand” for plastics, saying that “current bans and taxes are insufficient.” The organization recommended a suite of ideas that could make it more expensive for companies to churn out plastics: Fees could force companies to assume the costs of waste management and collection; governments could take away fossil fuel subsidies.

In response to Grist’s request for comment, Joshua Baca, vice president of plastics for the trade group the American Chemistry Council, said that plastic companies already supported many of the OECD’s recommendations, including recycled content standards and “improving access to waste collection.”

Carroll Muffett, president and CEO of the advocacy group Center for International Environmental Law, said that many of the OECD’s recommendations were well-intentioned, but wished the report had placed a greater emphasis on limiting plastic production. Characterizing plastic pollution as a mismanaged waste problem, he said, can distract decision-makers from policies designed to create less waste in the first place.

This is the point that hundreds of advocacy groups and scientists have been making in the lead-up to this month’s U.N. Environment Assembly meeting in Nairobi, Kenya. In December, more than 700 civil society groups, workers and trade unions, Indigenous peoples, women’s and youth groups, and others urged U.N. member states to craft a legally binding agreement that includes strategies to wind down global plastic production. Roughly 90 companies and more than 2 million individuals have made similar appeals.

“If you only focus on the demand side of the equation without addressing the expansion of that production capacity,” Muffett said, “then you are always chasing the problem and never catching it.”

Are microbes the future of recycling? It's complicated

Since the first factories began manufacturing polyester from petroleum in the 1950s, humans have produced an estimated 9.1 billion tons of plastic. Of the waste generated from that plastic, less than a tenth of that has been recycled, researchers estimate. About 12 percent has been incinerated, releasing dioxins and other carcinogens into the air. Most of the rest, a mass equivalent to about 35 million blue whales, has accumulated in landfills and in the natural environment. Plastic inhabits the oceans, building up in the guts of seagulls and great white sharks. It rains down, in tiny flecks, on cities and national parks. According to some research, from production to disposal, it is responsible for more greenhouse gas emissions than the aviation industry.

This pollution problem is made worse, experts say, by the fact that even the small share of plastic that does get recycled is destined to end up, sooner or later, in the trash heap. Conventional, thermomechanical recycling — in which old containers are ground into flakes, washed, melted down, and then reformed into new products — inevitably yields products that are more brittle, and less durable, than the starting material. At best, material from a plastic bottle might be recycled this way about three times before it becomes unusable. More likely, it will be “downcycled” into lower value materials like clothing and carpeting—materials that will eventually be disposed of in landfills.

“Thermomechanical recycling is not recycling,” said Alain Marty, chief science officer at Carbios, a French company that is developing alternatives to conventional recycling.

“At the end,” he added, “you have exactly the same quantity of plastic waste.”

Carbios is among a contingent of startups that are attempting to commercialize a type of chemical recycling known as depolymerization, which breaks down polymers — the chain-like molecules that make up a plastic — into their fundamental molecular building blocks, called monomers. Those monomers can then be reassembled into polymers that are, in terms of their physical properties, as good as new. In theory, proponents say, a single plastic bottle could be recycled this way until the end of time.

But some experts caution that depolymerization and other forms of chemical recycling may face many of the same issues that already plague the recycling industry, including competition from cheap virgin plastics made from petroleum feedstocks. They say that to curb the tide of plastic flooding landfills and the oceans, what’s most needed is not new recycling technologies but stronger regulations on plastic producers — and stronger incentives to make use of the recycling technologies that already exist.

Buoyed by potentially lucrative corporate partnerships and tightening European restrictions on plastic producers, however, Carbios is pressing forward with its vision of a circular plastic economy — one that does not require the extraction of petroleum to make new plastics. Underlying the company’s approach is a technology that remains unconventional in the realm of recycling: genetically modified enzymes.

Enzymes catalyze chemical reactions inside organisms. In the human body, for example, enzymes can convert starches into sugars and proteins into amino acids. For the past several years, Carbios has been refining a method that uses an enzyme found in a microorganism to convert polyethylene terephthalate (PET), a common ingredient in textiles and plastic bottles, into its constituent monomers, terephthalic acid, and mono ethylene glycol.

Although scientists have known about the existence of plastic-eating enzymes for years — and Marty says Carbios has been working on enzymatic recycling technology since its founding in 2011 — a discovery made six years ago outside a bottle-recycling factory in Sakai, Japan helped to energize the field. There, a group led by researchers at the Kyoto Institute of Technology and Keio University found a single bacterial species, Ideonella sakaiensis, that could both break down PET and use it for food. The microbe harbored a pair of enzymes that, together, could cleave the molecular bonds that hold together PET. In the wake of the discovery, other research groups identified other enzymes capable of performing the same feat.

Enzymatic recycling’s promise isn’t limited to PET; the approach can potentially be applied to other plastics, including polyurethane, used in in foam, insulation, and paint. But PET offers perhaps the most expansive commercial opportunity: It is one of the largest categories of plastics produced, widely used in food packaging and fabrics. PET-based beverage bottles are among the easiest plastics to collect and recycle into a marketable product.

Alain Marty, scientific director of Carbios, attends the inauguration of the company’s demonstration facility in Clermont-Ferrand, France, in September 2021.

Visual: Thierry Zoccolan/AFP via Getty Images

Traditional depolymerization technologies rely on inorganic catalysts rather than enzymes. But some chemical recycling companies have struggled in efforts to turn PET recycling into a viable business model — with some even facing legal scrutiny.

Despite this, Marty says that Carbios’ enzyme-based approach offers advantages over traditional depolymerization methods: The enzymes are more chemically selective than synthetic catalysts — they can more precisely target specific sites on specific molecules — and could therefore yield purer product. Plus they work at relatively low reactor temperatures and do not require expensive, hazardous solvents.

Traditionally, however, the problem with enzymes has been that they work slowly and can destabilize under heat. In early experiments, it sometimes took weeks to process just a fraction of a batch of PET. In 2020, Marty and colleagues at Carbios, along with researchers in France, announced that they had engineered an enzyme — a so-called cutinase, naturally found in microbes that decompose leaves — that could withstand warmer temperatures and convert nearly an entire batch of PET into monomers in a matter of hours. The discovery dramatically boosted enzymatic recycling’s commercial prospects; In the 10 months that followed, Carbios’ stock price on the Euronext Paris exchange grew about eightfold.

Last September, Carbios began testing its technology at a demonstration facility near its headquarters in Clermont-Ferrand, France, about a two-hour drive west of Lyon. Used PET arrives here as thin, pre-processed flakes about one-fifth of an inch across. In a 16-foot-tall reactor, the flakes are mixed with the patented cutinase enzymes —produced by Denmark-based biotechnology company Novozymes — and warmed to a little above 140 degrees Fahrenheit. Within 10 hours, Marty says, 95 percent of the plastic fed to the reactor, the equivalent of 100,000 plastic bottles, can be converted into monomers, which are then filtered, purified, and prepared for use in plastic manufacturing. (The remaining 5 percent, made up of unreacted plastic and impurities, is incinerated.) As Marty describes it, the end product is physically indistinguishable from the petrochemical-based substances used to manufacture virgin PET.

Carbios’ recycling technology has grabbed the attention of some of the world’s largest consumer goods companies. L’Oréal, Nestlé, and PepsiCo have collaborated with the startup to produce proof-of-concept bottles, and all seem intent on eventually putting enzyme-recycled plastic on shelves.

But Kate Bailey, the policy and research director at Eco-Cycle, a nonprofit recycler based in Colorado, says that over her 20 years in the recycling industry, she has grown skeptical of biotechnology fixes like the one being touted by Carbios. While she acknowledges that new solutions are needed, given the urgency of the plastic problem, she says “we don’t have more years to figure this out and wait for new technology.” Bailey points to lingering questions about how enzymatic recycling will be scaled up to handle commercial volumes, including questions about its energy footprint and its handling of toxic chemical additives found in many consumer plastics.

Marty concedes that Carbios’ process is, indeed, more energy-intensive than conventional recycling — he declined to specify by how much — but added that it’s not fair to compare enzymatic recycling with thermomechanical processes, which don’t produce as high quality of a recycled product and eventually result in the same quantity of waste. Still, he said, it requires less energy, and releases less greenhouse gas, than producing virgin PET from petroleum — claims that are supported by an independent analysis published last year by the U.S. National Renewable Energy Laboratory. As for additives, he says they are filtered out during post-reaction processing and incinerated.

In the Carbios laboratory, several plastic samples sit on the lab bench.

Visual: Thierry Zoccolan/AFP via Getty Images

A small-scale reactor mixes plastic and enzymes in the Carbios laboratory.

Visual: Thierry Zoccolan/AFP via Getty Images

In the Carbios demonstration plant, PET flakes and the patented cutinase enzymes mix in the large reactor tank on the right. Within 10 hours, 95 percent of the plastic is converted into monomers, Marty says.

Visual: Carbios

But the most stubborn hurdle for Carbios and other enzymatic recycling hopefuls may be an economic one. “It’s super cheap to make virgin plastic, especially with the low price of oil,” said Bailey.

“You have to be able to sell your recycled PET against to some company that also has the option of buying virgin PET,” she added, “and when virgin is just cheaper, then that’s what companies buy.”

In its analysis, the National Renewable Energy Laboratory estimated that PET monomers produced through enzymatic recycling would carry a price of at least $1.93 per kilogram; virgin, petroleum-based monomers have ranged between $0.90 and $1.50 per kilogram since 2010. And now that many fossil fuel companies are pivoting their business models toward plastic production, the market competition for plastic recyclers could grow even stiffer.

Marty, however, is optimistic about his company’s prospects. He points out that the price of oil is rising and that tightening regulations on the use of fossil fuels in Europe is making recycled plastic more competitive there. Several consumer goods giants have publicly committed to sourcing more of their products from recycled materials: Coca-Cola pledged to use recycled material for half of its packaging by 2030, and Unilever aims to cut its reliance on virgin plastic in half by 2025.

“At the beginning, sure, it will be a little more costly,” Marty said. “But we will reduce, with experience, the cost of this recycled PET.”

Wolfgang Streit, a microbiologist at the University of Hamburg, says that even if companies achieve commercial success with PET, some polymers may never be amenable to the enzymatic recycling. Polymers like polyvinylchloride, used in PVC pipes, and polystyrene, used in Styrofoam, are held together by powerful carbon-carbon bonds, which might be too sturdy for enzymes to overcome, he explains.

That’s one reason Bailey believes new policies need to be considered alongside new technologies in addressing the global plastic waste problem. She advocates for measures that limit the production of hard-to-recycle plastics and improve collection rates for materials like PET, which can be recycled, albeit imperfectly, with existing technologies. Bailey notes that currently only about three in 10 PET bottles gets collected for recycling. She describes that as low-hanging fruit “that we could solve today with proven technology and policies.”

Now that many fossil fuel companies are pivoting their business models toward plastic production, the market competition for plastic recyclers could grow even stiffer.

Most PET produced globally is used not for bottles but for textile fibers, which, because they often contain blended materials, are rarely recycled at all. Mats Linder, the head of the consulting arm of Stena Recycling in Sweden, said he’d like to see chemical recycling technologies focus on these and other parts of the recycling industry where conventional recycling is coming up short.

As it happens, Carbios is working to do just that, Marty says. The French company Michelin has validated the company’s technology, which could allow it to recycle used textiles and bottles into tire fibers. It aims to launch a textile recycling operation in 2023, and Marty says the company is on track to launch a 44,000-ton-capacity industrial scale facility in 2025.

Gregg Beckham, a senior research fellow at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory, believes the global plastic problem will call for a diverse mix of technological and policy solutions, but he says enzymatic recycling and other chemical recycling technologies are advancing rapidly, and he’s optimistic that they will have a role to play. “I think chemical recycling is useful in the contexts where other solutions don’t work,” he said. “And there are many places where other solutions don’t work.”

Ula Chrobak is a freelance science writer based in Nevada. You can find more of her work at her website.