It’s easy to feel despondent about the state of the global environment in 2021. More than a million species are at risk of extinction, levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere continue to increase, and the planet was rocked by a series of climate change-fueled extreme weather events. Meanwhile, the world continues to grapple with a deadly pandemic that seems like it will never end.But, as the year draws to a close, there are reasons to feel cautiously optimistic about areas in which the environment scored victories in 2021.It’s important to note that even these promising developments involve pledges that may yet be watered down, misleading, or altogether unfulfilled. Still, there are signs of success on this long, difficult road. Here are five reasons to be hopeful.1. Pushback on fossil fuelsCoal is sold on the streets of Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia, which then pollutes the air when burned. Countries at November’s Glasgow UN Climate Conference pledged to reduce the amount of coal they produced.Photograph by Matthieu Paley, Nat Geo Image CollectionPlease be respectful of copyright. Unauthorized use is prohibited.Delayed by a year as a result of COVID-19, November’s COP26—the United Nations Climate Change Conference, held in Glasgow—welcomed the world’s second-largest fossil-fuel emitter, the United States, back to the negotiating table after four years of inaction on climate change. By the summit’s end, the U.S. and China had made a surprise joint declaration to work together on meeting the goals of the Paris Agreement.While the level of ambition at Glasgow faced plenty of criticism, particularly in terms of protecting developing countries from climate impacts and supporting their transitions to clean energy systems, the goal of keeping warming to 2.7°F (1.5°C) is arguably more achievable now. Notably, countries agreed to “phase down” their coal use—which fell short of an initial draft to “phase out” coal—and more than a hundred countries agreed to cut their methane emissions 30 percent by 2030.Away from Glasgow, the Biden administration canceled the controversial Keystone XL pipeline and suspended oil drilling leases in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, though it is also opening up millions of acres to oil and gas exploration. The administration set a goal of generating 30 gigawatts of offshore wind by 2030 and announced its intention to reduce solar energy costs 60 percent over the next decade; the two declarations are part of a plan to have the U.S. powered by a clean grid by 2035. In addition, President Joe Biden in August mandated that by 2030, half of all new vehicles sold in the U.S. be electric.Globally, renewable energy use in 2021 is expected to increase by 8 percent, the fastest year-on-year-growth since the 1970s, while in the U.S., a new report found that it had nearly quadrupled over the last decade.In the Netherlands, a court ordered Royal Dutch Shell to reduce its carbon emissions by 45 percent relative to 2019 levels by 2030, a result one lawyer described as a “turning point in history.”2. Progress on plasticSeveral U.S. states passed legislation in 2021 to reduce the amount of plastic entering the environment; some states send their plastic waste to countries such as the Philippines, pictured here. The U.S. is the biggest plastic polluter in the world.Photograph by Randy Olson, Nat Geo Image CollectionPlease be respectful of copyright. Unauthorized use is prohibited.The last 12 months saw a raft of legislation to reduce growing plastic pollution. In Washington State, Governor Jay Inslee signed a law that bans polystyrene products, such as foam coolers and packing peanuts; requires that customers must request single-use utensils, straws, cup lids, and condiments; and mandates minimum post-consumer recycled content in a number of plastic bottles and jugs, including those for personal care products and household cleaning.California passed landmark bills that, among other things, prohibit manufacturers from placing the “chasing arrows” recycling symbol or the word recyclable on items that aren’t actually recyclable; forbid mixed plastic waste exports to other countries being counted as “recycled,” just so that local governments can claim to comply with state laws; require products labeled as compostable to break down in real-life conditions; and ban the use of extremely long-lasting PFAs, known as forever chemicals, in children’s products.Such actions may be reflected federally following the introduction of the Break Free from Plastic Pollution Act; among other things, the proposal by two U.S. lawmakers would ban some single-use plastic products and pause permits of new plastics manufacturing plants.In November, U.S. Secretary of State Anthony Blinken announced that the U.S. would back a global treaty to tackle plastic pollution; the Trump administration opposed it. U.S. support is critical, given that the nation is the world’s largest contributor to plastic waste, as revealed in a congressionally mandated report released in December. The treaty now seems certain to move forward, and the United Nations is scheduled to convene in Nairobi in February to begin formal negotiations.In December, the National Academies of Sciences urged the U.S., which generates more plastic waste than all the European Union states combined, to develop a strategy to reduce it, including a national cap on virgin plastic production.3. Protection of forestsSome local governments in Indonesia are yanking palm oil permits from companies seeking to build plantations in forest.Photograph by Pascal Maitre, Nat Geo Image CollectionPlease be respectful of copyright. Unauthorized use is prohibited.By far the biggest news in forest conservation was the pledge at the UN Climate Conference in Glasgow to end deforestation by 2030; the commitment includes a pledge to provide $12 billion in funding to “help unleash the potential of forests and sustainable land use.” However, the promise was met with widespread skepticism, not least because deforestation rates actually increased following a 2014 agreement with the same goal.However, 2021 did see a number of on-the-ground victories. In October, President Felix Tshisekedi of the Democratic Republic of Congo called for an audit of its vast forest concessions and the suspension of all “questionable contracts” until the audit is done. A few weeks later, the government retreated from a plan to lift a 19-year-old moratorium on the granting of new logging licenses in the Congo Basin Forest. “We don’t want any more contracts with partners who came to savagely cut our forests; we will retire these types of contracts,” said Environment Minister Eve Bazaiba. Environmental groups remain wary, and Greenpeace is calling for the DRC moratorium to be made permanent.The government of the Indonesian province of West Papua revoked permits for 12 palm oil contracts covering more than 660,000 acres (an area twice the size of Los Angeles), three-fifths of which remains forested. Environmental and Indigenous rights groups are urging the government to go further and recognize the rights of Native peoples in those areas to manage the forests themselves. Three of the 12 contract holders continue to fight the government’s decision in court.And Ecuador’s highest court has ruled that plans to mine for copper and gold in a protected cloud forest would harm its biodiversity and violate the rights of nature, which are enshrined in the Ecuadorian constitution. The ruling means that mining concessions, and environmental and water permits in the forest, must be cancelled.4. Restoration of habitatsA male sage grouse in Wyoming. This year, a court overturned a Trump administration decision that impacted the habitat of the sage grouse. Photograph by Charlie Hamilton James, Nat Geo Image CollectionPlease be respectful of copyright. Unauthorized use is prohibited.The Biden administration spent part of its first year restoring habitat protections that had been rolled back by its predecessor. Perhaps the most prominent was the re-establishment of full protection for the Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante monuments in southern Utah, as well as the Northeast Canyons and Seamounts National Monument off New England.The administration restored protection to more than 3 million acres of old-growth forest in the Pacific Northwest that is critical habitat for the northern spotted owl. It also reversed an effort to weaken the Migratory Bird Treaty that the Trump White House set in motion in its last few days in office. Meanwhile, a court overturned a Trump administration decision to strip protections from 10 million acres, mostly in Nevada and Idaho, to allow mining in critical habitat for greater sage-grouse.In May, the Biden administration unveiled its America the Beautiful initiative, which among other things established the first-ever national conservation goal: conserving 30 percent of U.S. lands and waters by 2030. It reflects a United Nations aim to protect the same percentage of land and ocean, an objective to which more than 100 nations committed in September.In November, Colombia pledged to protect 30 percent of its land by 2022. And Panama took major steps toward the same goal by tripling the size of its Cordillera de Coiba Marine Protected Area. Also in November, Portugal established the largest fully protected marine reserve in Europe.5. Support for wildlifePopulations of giant pandas have recovered enough for China to remove the bears from the endangered species list. Photograph by Ami Vitale, Nat Geo Image CollectionPlease be respectful of copyright. Unauthorized use is prohibited.Populations of some of the world’s most iconic species are showing some improvement as a result of protective measures. In July, China announced that it no longer considers the giant panda, the symbol of the World Wildlife Fund, to be endangered, upgrading its status to vulnerable. Just over 1,800 pandas remain in the wild, an improvement over the 1,100 thought to live in the wild as recently as 2000. Meanwhile, China announced the creation of the Giant Panda National Park, part of a system of new parks that will cover an area nearly the size of the United Kingdom. The parks are designed to protect native species such as the Northeast China tiger, Siberian leopard, and the Hainan black-crested gibbon.Humpback whales, whose haunting songs helped build support for the “Save the Whales” campaign that ushered in the modern environmental movement, are increasing in number in many parts of their range, including off Australia (where the government is considering removing them from the country’s threatened list) and in their South Atlantic feeding grounds. That said, the number of calves in the Northwest Atlantic population has declined over the last 15 years.Several species of tuna are no longer heading toward extinction, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature. Two bluefin species, a yellowfin, and an albacore are no longer classified as critically endangered or have moved off the leading international list of endangered species entirely, the result of decades of efforts to limit the impacts of commercial fishing.Three thousand years after the species was eliminated everywhere except its eponymous island, seven Tasmanian devils were born in a reserve in mainland Australia. Scientists hope that if the marsupials one day again become established on the mainland, they could play a vital role in controlling invasive species.And in the U.K., a government report concluded that lobsters, crabs, and octopuses are sentient beings that feel pain, and as a result should be granted protection under the country’s draft Animal Welfare (Sentience) Bill.

Category Archives: Plastic Pollution Articles & News

Microplastics cause damage to human cells, study shows

Microplastics cause damage to human cells, study showsHarm included cell death and occurred at levels of plastic eaten by people via their food Microplastics cause damage to human cells in the laboratory at the levels known to be eaten by people via their food, a study has found.The harm included cell death and allergic reactions and the research is the first to show this happens at levels relevant to human exposure. However, the health impact to the human body is uncertain because it is not known how long microplastics remain in the body before being excreted.Microplastics pollution has contaminated the entire planet, from the summit of Mount Everest to the deepest oceans. People were already known to consume the tiny particles via food and water as well as breathing them in.The research analysed 17 previous studies which looked at the toxicological impacts of microplastics on human cell lines. The scientists compared the level of microplastics at which damage was caused to the cells with the levels consumed by people through contaminated drinking water, seafood and table salt.They found specific types of harm – cell death, allergic response, and damage to cell walls – were caused by the levels of microplastics that people ingest.“Harmful effects on cells are in many cases the initiating event for health effects,” said Evangelos Danopoulos, of Hull York Medical School, UK, and who led the research published in the Journal of Hazardous Materials. “We should be concerned. Right now, there isn’t really a way to protect ourselves.”Future research could make it possible to identify the most contaminated foods and avoid them, he said, but the ultimate solution was to stop the loss of plastic waste: “Once the plastic is in the environment, we can’t really get it out.”Research on the health impact of microplastics is ramping up quickly, Danopoulos said: “It is exploding and for good reason. We are exposed to these particles every day: we’re eating them, we’re inhaling them. And we don’t really know how they react with our bodies once they are in.”The research also showed irregularly shaped microplastics caused more cell death than spherical ones. This is important for future studies as many microplastics bought for use in laboratory experiments are spherical, and therefore may not be representative of the particles humans ingest.“This work helps inform where research should be looking to find real-world effects,” said microplastics researcher Steve Allen. “It was interesting that shape was so important to toxicity, as it confirms what many plastic pollution researchers believed would be happening – that pristine spheres used in lab experiments may not be showing the real-world effects.” Danopoulos said the next step for researchers was to look at studies of microplastic harm in laboratory animals – experiments on human subjects would not be ethical. In March, a study showed tiny plastic particles in the lungs of pregnant rats pass rapidly into the hearts, brains and other organs of their foetuses.In December, microplastics were revealed in the placentas of unborn babies, which the researchers said was “a matter of great concern”. In October, scientists showed that babies fed formula milk in plastic bottles were swallowing millions of particles a day.TopicsPlasticsPollutionHealthReuse this content

Styrofoam trash adds to antibiotic resistance crisis

Share this Article

You are free to share this article under the Attribution 4.0 International license.

Hiding in plain sight: How plastics inflame the climate crisis

Plastic is ubiquitous, filling stores, overtopping landfills and littering shorelines.

It’s even within us, since residual plastic particles now lace air, water and food. While the hazards posed by microplastics are still emerging, an obvious peril has been hiding in plain sight: Plastic derives from fossil fuels, and worsens climate threats throughout its life cycle.

Look down a supermarket aisle lined with chip bags and soda bottles, and chances are you don’t visualize the flaring gas from a shale drilling operation. That might change if you read “The New Coal: Plastics and Climate Change.”

This report, commissioned by the Vermont-based nonprofit Beyond Plastics, highlights how much greenhouse gas pollution plastics emit — in fossil fuel extraction, manufacturing, incineration, landfills and long-term degradation (potentially spanning centuries).

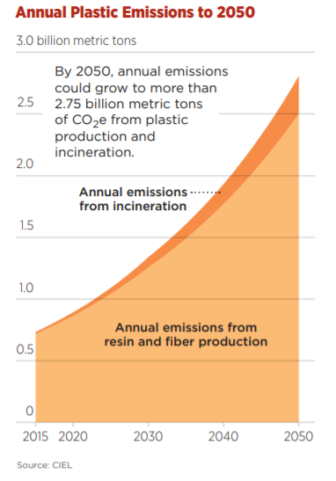

Source: Center for International Environmental Law

Climate-disrupting emissions from the plastic industry could surpass those from coal production in the U.S. by 2030, the report warns. Given emissions from more than 130 existing facilities, new plants under construction and other industry sources, U.S. plastics could generate the carbon dioxide equivalent of 143 mid-sized coal-fired plants.

Yet policy makers and regulators have largely overlooked plastics. Maine’s 2020 Climate Action Plan, for example, holds virtually no mention of plastics, waste reduction, trash incineration or recycling.

“Massive blind spots in policy at local, state and federal levels have allowed plastics to go under the radar,” said Jim Vallette, president of Maine-based Material Research L3C and author of the recent report.

It’s time to bring plastic’s climate risks into clear view.

Just another form of fossil fuel

Greenhouse gas emissions from global plastics industries stand just behind those of the worst carbon-polluting nations: China, the U.S., India and Russia. At the recent U.N. Climate Summit in Glasgow, Scotland, multinational fossil fuel interests — which include petrochemical and plastics industries — had a stronger presence than any single country, with more than 500 industry representatives (whereas, the U.S. had 165 delegates).

Fossil fuel corporations are pivoting to plastic production to keep afloat, given the existential threat posed by dropping prices of renewable power and increasing electric vehicle adoption. Global plastics production is expected to double by 2040, becoming the biggest growth market for fossil fuel demand, the International Energy Agency (IEA) and BP both forecast.

U.S. plastic production draws primarily on ethane gas from hydraulically fractured shale, an abundant resource since the fracking boom that began in 2008. For the eastern U.S., the federal Department of Energy in 2018 projected a 20-fold increase in ethane production over 2013 levels by 2025.

Toxic manufacturing clusters

Following pipeline transport from fracked wells, ethane gas is steam-heated in “ethane cracker” plants until it breaks into new molecules, forming the ethylene used in plastic manufacturing. This energy-intensive process generates high levels of carbon dioxide, and pollutants such as volatile organic compounds and benzene.

Credit: Beyond Plastics

Most plastic manufacturing occurs near the Gulf of Mexico in Texas and along Louisiana’s “Cancer Alley,” a region notorious for its high and growing concentration of petrochemical plants.

The New Coal report found that more than 90 percent of climate pollution reported to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) by the plastics industry is released into 18 communities, noting that “people living within three miles of these petrochemical clusters earn 28 percent less than the average U.S. household and are 67 percent more likely to be people of color.”

The world’s largest ethane cracker plant, a joint venture between ExxonMobil and Saudi Arabia’s state-owned petroleum corporation, is nearing completion outside Portland, Texas. Sprawling across a 1,300-acre site, the plant lies less than two miles from area schools and in full view of a low-income housing complex. Communities have fought against these facilities but with limited success.

The myth of plastic recycling

Many of the ethane cracker plants being built will produce single-use plastics such as bottles, sachets and straws. Plastic items often bear recycling symbols, but few actually get recycled. The latest EPA data from 2018 indicates that fewer than 9 percent of plastics were recycled, while 17 percent were incinerated and 69 percent were landfilled.

At least 115 towns in Maine currently lack any recycling option, with all household waste either landfilled or incinerated. Maine has three municipal waste incinerators operating: in Portland, Auburn and Orrington. Each was built decades ago, when plastic represented roughly 10 percent of the waste stream. That figure has nearly doubled, Vallette said.

Higher plastic content adds to the carbon dioxide incinerators emit, and can introduce chemicals that are potent warming agents. Vallette has calculated that fluoropolymers, highly persistent PFAS resins used in wiring insulation, may have up to 10,000 times more potential for global warming than carbon dioxide.

Petrochemical corporations have misled consumers for decades by promoting plastic recycling while knowing it was not feasible. The industry also ran repeated ad campaigns to convince consumers that the problem was not with plastic itself, but with irresponsible litterbugs.

Changes in Maine, Oregon

Now consumers have caught on. States like Maine and Oregon are taking a new regulatory approach that holds producers responsible for the packaging they produce.

Maine’s pioneering Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) law will drastically cut the plastic industry’s “greenwashing capability,” observed Sarah Nichols, Sustainable Maine program director for the Natural Resources Council of Maine. “We’re going to finally get the data we need to make meaningful change. It’s a whole new system.”

Similar programs in other countries have increased recycling rates and reduced waste generation — two measures that could markedly cut Maine’s greenhouse gas emissions.

Maine has never met its statutory goal for recycling, set in 1989, of 50 percent. Today, only about 36 percent of waste is even collected for recycling (and the percentage getting recycled is likely much less). If the state met its original goal, Nichols estimates, the reduction in carbon pollution would be equivalent to taking roughly 166,000 passenger cars off the road.

Action at all levels — from local to global

“The inevitable, logical next step,” Vallette observed, “is to minimize plastic entering the waste stream.”

Purchasing less plastic, supporting retailers that offer bulk and refillable goods, instituting bans (like Maine’s recent one on single-use plastic bags) and holding producers to account through EPR laws should help. The state also needs to address plastics in the ongoing work of the Maine Climate Council, compensating for the notable absence of waste reduction targets in the 2020 Climate Action Plan.

A federal EPR bill, the Break Free from Plastic Pollution Act, has garnered more than 100 co-sponsors already, but given the power of the plastics lobby, its passage is far from assured. Among Maine’s delegation, only U.S. Rep. Chellie Pingree has cosponsored the legislation to date.

Congress must also reassess billions of dollars in federal subsidies going annually to the fossil fuel industry. According to a 2020 report by the research nonprofit Carbon Tracker, the global plastics industry receives $12 billion in subsidies annually while paying just $2 billion in taxes and racking up an estimated $350 billion a year in unpaid “externalities” — including marine debris, air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions.

“In the next few years,” the IEA wrote in a report earlier this year, “all governments need to eliminate fossil fuel subsidies.”

Peter Dykstra: Environmental “solutions” too good to be true

I’ve long been fascinated with Thomas Midgley Jr. In the 1920’s and 1930’s, he was on his way to joining Thomas Edison and Benjamin Franklin as one of the GOATs of science and invention.Midgley’s two giant discoveries changed lives – in a good way to start, but then in tragic ways. He discovered that tetraethyl lead (TEL) eliminated engine knock, a scourge of early motorists. And his development of chlorofluorocarbon chemicals (CFC’s) as refrigerants revolutionized air conditioning and food storage.He was a science rock star, until we learned that the lead in TEL was a potent neurotoxin, impairing child brain development; and CFC’s were destroying Earth’s ozone layer.Oops. He’s not alone—all too often we “solve” health and environment problems only to learn we’ve created bigger ones.

Miracle chemicals

Midgley never won a Nobel Prize, but Swiss chemist Paul Müller did in 1948. Müller resurrected a long-forgotten synthetic chemical compound, dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane, or DDT. DDT showed a remarkable talent for eliminating some agricultural pests as well as human tormentors like lice and mosquitos. DDT is credited with enabling U.S. and Allied troops to drive Japan out of tropical forests in the Pacific.Scientist and author Rachel Carson exposed DDT’s other talent: Thinning birds’ eggshells, from tiny hummingbirds to raptors like the bald eagle. Bans in the U.S. (1972) and most other nations saved countless species from oblivion.

The peaceful atom

When nuclear weapons destroyed the Japan cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, ending World War II, there was little public dissent among Americans. The prevailing argument was that the hundreds of thousands of Japanese citizens killed by the blasts would seem like small potatoes compared to the death toll from a land invasion.Into the 1950’s, the USSR strove to catch up to the U. S. Through the 1950s and the height of the Cold War, the “Peaceful Atom” became a civic goal. Atomic Energy Commission Chair Lewis L. Strauss saw a future with “electricity too cheap to meter”. The Eisenhower Administration proposed creating a deepwater port at Point Hope, Alaska, by nuking a crater in the Arctic Ocean.In the 1960’s and 1970’s, fervor to build nuclear power plants grew, then began to wane as concerns about costs, nuclear waste disposal, and safety grew. If the 1979 near-disaster at Three Mile Island chilled Wall Street’s interest in commercial nuclear power, the calamitous 1986 Chernobyl meltdown nearly finished it off.

Bridge fuel?

Nuke power’s “carbon-free” status kept industry hopes alive for a bit. Then in the early 2000’s, with oil men George W. Bush and Dick Cheney at the helm, came a bold play by the oil and gas industry.Hydraulic fracturing — fracking – was a relatively new take on extracting natural gas from previously unreachable places. Fracking promised a “bridge fuel” that could wean Americans off dirtier fossil fuels en route to a clean energy future.So tempting was the bridge fuel pitch that the venerable Sierra Club took in an estimated $25 million from fracking giant Chesapeake Energy to help Sierra’s “Beyond Coal” campaign. Meanwhile, cheap fracked gas undercut both coal and nuclear in energy markets just as multiple trolls peeked out from beneath the bridge: Fracking’s huge climate impacts from methane releases and its rampant use of water and toxic chemicals.

But wait…there’s more!

Years of clogged landfills and trash-choked creeks highlight the worldwide failure of plastics recycling.Plastic packaging made life easier for all of us. And easier. And easier. According to the U.N. Environment Programme (UNEP), we now use 5 trillion single-use plastic bags per year. A tiny fraction are actually recycled. The rest find virtually indestructible homes in landfills or oceans. Or, with domestic plastics recycling waning, they’re shipped to the dwindling number of developing nations that will accept them.We’re failing to learn a century’s worth of lessons from Midgley to DDT to nukes to fracking to plastics. Maybe the least we can do is make sure our solutions actually solve things.

Peter Dykstra is our weekend editor and columnist and can be reached at pdykstra@ehn.org or @pdykstra.His views do not necessarily represent those of Environmental Health News, The Daily Climate, or publisher Environmental Health Sciences.Banner photo credit: OCG Saving The Ocean/Unsplash

From Your Site Articles

David Attenborough’s unending mission to save our planet

WE MAKE LOTS of programs about natural history, but the basis of all life is plants.” Sir David Attenborough is at Kew Gardens on a cloudy, overcast August day waiting to deliver his final piece to camera for his latest natural history epic, The Green Planet. Planes roar overhead, constantly interrupting filming, and he keeps putting his jacket on during pauses. “We ignore them because they don’t seem to do much, but they can be very vicious things,” he says. “Plants throttle one another, you know—they can move very fast, have all sorts of strange techniques to make sure that they can disperse themselves over a whole continent, have many ways of meeting so they can fertilize one another and we never actually see it happening.” He smiles. “But now we can.”Attenborough occupies a unique place in the world. Born on May 8, 1926, the year before television was invented, he is as close to a secular saint as we are likely to see, respected by scientists, entertainers, activists, politicians, and—hardest of all to please—kids and teenagers.In 2018, he was voted the most popular person in the UK in a YouGov poll. So many Chinese viewers downloaded Blue Planet II “that it temporarily slowed down the country’s internet,” according to the Sunday Times. In 2019, Attenborough’s series Our Planet became Netflix’s most-watched original documentary, viewed by 33 million people in its first month, and the NME reported that his appearance on Glastonbury’s Pyramid stage where he thanked the crowd for accepting the festival’s no-single-use-plastic policy attracted the weekend’s third-largest crowd after Stormzy and The Killers.On September 24, 2020, the 95-year-old broke the Guinness World Record for attracting 1 million followers just four hours and 44 minutes after he joined Instagram, beating the previous record holder, Jennifer Aniston, by over 30 minutes. His first post was a video clip where he set out his reasons for signing up. “The world is in trouble,” he explained, standing in front of a row of trees at dusk in a light blue shirt and emphasizing each point with a sorrowful shake of the head. “Continents are on fire, glaciers are melting, coral reefs are dying, fish are disappearing from our oceans. But we know what to do about it, and that’s why I’m tackling this new way, for me, of communication. Over the next few weeks, I’ll be explaining what the problems are and what we can do. Join me.”The public response was so overwhelming that he left the platform 27 posts and just over a month later, after being inundated with messages. He’s always tried to reply to every communication he receives and can just about manage the 70 snail-mail letters he gets every day. Wherever he appears—wherever his team at the BBC’s Natural History Unit point their lenses—hundreds of millions of people will be watching. And right now, in the year of COP26, The Green Planet hopes to do for plants what Attenborough has done for oceans and animals … create understanding and encourage us to care.The Green Planet, as is typical with all Attenborough/BBC Natural History Unit productions, contains a number of firsts—technical firsts, scientific firsts, and just a few never-before-seen firsts. But it also includes one great reprise. Attenborough is out in the field again for the first time since 2008’s Life in Cold Blood, traveling to rainforests and deserts and revisiting some places he passed through decades ago.Two moments stand out. In the first, Attenborough is explaining the biology of the seven-hour flower—Brazil’s Passion Flower, Passiflora mucronate, which opens around 1 am and closes again sometime between 7 am and 10 am. The white, long-stalked flower is pollinated by bats which gorge on its nectar, allowing pollen to brush on the bats’ heads. As Attenborough watches one flower open, a bat appears and flutters up to feed. Attenborough laughs with delight.Later, the series examines the creosote bush, one of the oldest living organisms on Earth at 12,000 years old. A desert dweller, it’s adapted to the harsh conditions by preserving energy and water through an incredibly slow rate of growth—1 millimeter a year. The team at the Natural History Unit used Attenborough’s long experience to illustrate something even the slowest time lapse camera would struggle to capture.“Sir David went to this particular desert and to a particular creosote bush when he did Life on Earth in 1979,” Mike Gunton, the BBC’s Natural History Unit’s creative director, explains. “We’ve gone back to exactly the same creosote bush and had David stand in exactly the same place and matched the shot from 1979 with the shot in 2019. So, we’ve used his human lifetime to illustrate how slowly this plant has grown. We’ve used the fact that he has traveled the world throughout his life on a number of occasions. He bears witness to the changes, and I think it’s rather lovely, actually.”For the rest of the footage the unit turned to what it does best—hacking brand new equipment and pushing it to extreme limits in a bid to film the previously unfilmable and bring the hidden aspects of the natural world to our screens.Previous firsts include the unit using the high-speed Phantom camera, which can shoot 2,000 frames per second, in 2012 to prove that a chameleon’s tongue isn’t sticky but muscular, wrapping itself around its prey rather than adhering to it. Or hacking the RED Epic Monochrome, a black-and-white camera with a sensor that can film 300 frames per second (an iPhone films at 25 frames per second), removing the cut-pass filter, which filters out infrared light from camera chips as it can blur color images. This added sensitivity to a night shoot in the Gobi Desert, allowing the third-ever filming of the long-eared jerboa, a rodent less than ten centimeters long and entirely nocturnal.Plants may seem less complicated—and less exciting—than a near-invisible nocturnal rodent in a vast Mongolian desert, but the unit’s approach intends to prove otherwise. The best place to show this is in a Devon farmhouse with a robot called Otto and a hunter-killer vine that’s slaughtering its prey.“We have cameras that can take a demonstration of a parasitic plant throttling another plant to death. It’s dramatic stuff,” Attenborough says gleefully.

Report says fixing plastics' pollution in the oceans requires a new approach

Millions of tons of plastic waste end up in the ocean every year. Scientists are calling on the federal government to come up with a comprehensive policy to stop it.

NOEL KING, HOST:

The U.S. produces more plastic waste than any country in the world, and a new report from Congress says we have to rethink how we use plastic. Here’s NPR’s Lauren Sommer.

LAUREN SOMMER, BYLINE: Every year, almost 10 million tons of plastic goes into the ocean. That’s like having a full garbage truck unloading its waste into the water every minute for an entire year.

KARA LAVENDER LAW: We’re really good at buying things and using them and making trash.

SOMMER: Kara Lavender Law is an oceanographer at the Sea Education Association and is an author of a new report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine about plastics in the ocean. She says plastic takes a huge toll on marine life, both because animals get trapped in it and because they eat it. Birds on Pacific Islands have been found with stomachs full of plastic bits.

LAW: We create these materials, and we need to be responsible for them through their end of life.

SOMMER: Law says their report calls on the U.S. to create a national plastic strategy by the end of next year. One part of the puzzle – recycling because most of us are doing aspirational recycling.

LAW: You know, you put something in the blue bin and you assume that it just magically turns into the next thing.

SOMMER: But in the U.S., only about 9% of plastic waste is recycled. The problem is that many items have several kinds of plastic in them, so they can’t be recycled or take a lot of work to separate, which makes it expensive. Winnie Lau, who works on plastics policy at the Pew Charitable Trusts, says there needs to be a bigger market for recycled plastic.

WINNIE LAU: Having governments and companies commit to using the recycled plastic will really go a long way.

SOMMER: Another key strategy – stop using plastic in the first place by switching to biodegradable materials. The American Chemistry Council, which represents plastics manufacturers, says that would lead to increased costs for consumers. Lau says recycling alone won’t solve the problem, and it’s getting more urgent.

LAU: Even a five-year delay would add about 100 million metric tons of plastic into the ocean over that five years.

SOMMER: But it’s not hopeless, she says. It will just take a national strategy where one has been lacking.

Lauren Sommer, NPR News.

(SOUNDBITE OF IL:LO’S “A.ME”)

Copyright © 2021 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by Verb8tm, Inc., an NPR contractor, and produced using a proprietary transcription process developed with NPR. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.

There's so much plastic floating on the ocean surface, it's spawning new marine communities

The North Pacific Subtropical Gyre, otherwise known as the “Great Pacific Garbage Patch,” is considered the world’s largest accumulation of ocean plastic. It’s so massive, in fact, that researchers found it has been colonized by species — hundreds of miles away from their natural home. The research, published in the journal Nature on Thursday, found that species usually confined to coastal areas — including crabs, mussels and barnacles — have latched onto, and unexpectedly survived on, massive patches of ocean plastic.

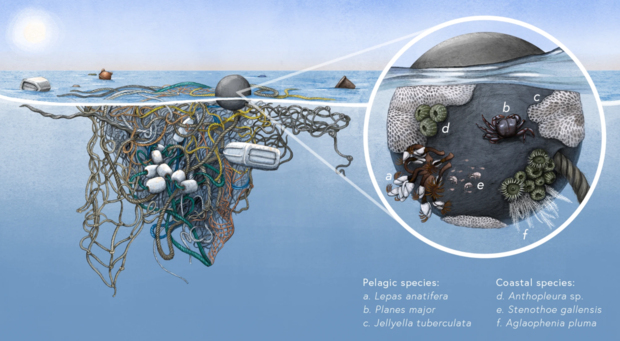

Neopelagic communities are composed of pelagic species, evolved to live on floating marine substrates and marine animals, and coastal species, once assumed incapable of surviving long periods of time on the high seas.

Illustrated by © 2021 Alex Boersma

Coastal species such as these were once thought incapable of surviving on the high seas for long periods of time. Only oceanic neuston, organisms that float or swim just below the ocean surface, have historically been found near these patches, as they thrive in open ocean.

But the mingling of the neuston and coastal species is “likely recent,” researchers said, and was caused largely because of the accumulation of “long-lived plastic rafts” that have been growing since the middle of the 20th century. Just by itself, the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, located between California and Hawai’i, is estimated to have at least 79,000 tons of plastic within a 1.6 million-square-kilometer area, according to research published in 2018. There are at least four other similar patches throughout the world’s oceans. And the accumulation of ocean plastic is only anticipated to get worse. Researchers expect that plastic waste is going to “exponentially increase,” and by 2050, there will be 25,000 million metric tons of plastic waste. This new community, researchers said, “presents a paradigm shift” in the understanding of marine biogeography.

“The open ocean has long been considered a physical and biological barrier for dispersal of most coastal marine species, creating geographic boundaries and limiting distributions,” researchers said. “This situation no longer appears to be the case, as suitable habitat now exists in the open ocean and coastal organisms can both survive at sea for years and reproduce, leading to self-sustaining coastal communities on the high seas.”For lead author Linsey Haram, the research shows that physical harm to larger marine species should not be the only concern when it comes to pollution and plastic waste. “The issues of plastic go beyond just ingestion and entanglement,” Haram said in a statement. “It’s creating opportunities for coastal species’ biogeography to greatly expand beyond what we previously thought was possible.” But that expansion could come at a cost. “Coastal species are directly competing with these oceanic rafters,” Haram said. “They’re competing for space. They’re competing for resources. And those interactions are very poorly understood.”There is also a possibility that expansions of these plastic communities could cause problems with invasive species. A lot of plastic found in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, for example, is debris from the 2011 Tohoku tsunami in Japan, which carried organisms from Japan to North America. Over time, researchers believe, these communities could act as reservoirs that will provide opportunities for coastal species to invade new ecosystems. There are still many questions researchers say need to be answered about these new plastic-living communities — like how common they are and if they can exist outside the Great Pacific Garbage Patch — but the discovery could change ocean ecosystems on a global scale, especially as climate change exacerbates the situation.

“Greater frequency and amounts of plastics on land, coupled with climate change-induced increases in coastal storm frequency ejecting more plastics into the ocean, will provide both more rafting material and coastal species inoculations, increasing the prevalence of the neopelagic community,” researchers said. “As a result, rafting events that were rare in the past could alter ocean ecosystems and change invasion dynamics on a global scale, furthering the urgent need to address the diverse and growing effects of plastic pollution on land and sea.”

Turtle travels from Maldives to Scotland after plastic pollution injury

U.S. is top contributor to plastic waste, report shows

“The developing plastic waste crisis has been building for decades,” the National Academy of Sciences study said, noting the world’s current predicament stems from years of technological advances. “The success of the 20th century miracle invention of plastics has also produced a global scale deluge of plastic waste seemingly everywhere we look.”The United States contributes more to this deluge than any other nation, according to the analysis, generating about 287 pounds of plastics per person. Overall, the United States produced 42 million metric tons of plastic waste in 2016 — almost twice as much as China, and more than the entire European Union combined.“The volume is astounding,” said Monterey Bay Aquarium’s chief conservation and science officer, Margaret Spring, who chaired the NAS committee, in an interview.The researchers estimated that between 1.13 million to 2.24 million metric tons of the United States’ plastic waste leak into the environment each year. About 8 million metric tons of plastic end up in the ocean a year, and under the current trajectory that number could climb to 53 million by the end of the decade.That amount of waste would be the equivalent to “roughly half of the total weight of fish caught from the ocean annually,” the report said.Congress last year ordered the National Academy of Sciences study, which drew on expertise from American and Canadian institutions, when it passed Save Our Seas 2.0 in an effort to address plastic waste.“This report is a sobering reminder of the scale of this problem,” the legislation’s co-author, Sen. Dan Sullivan (R-Alaska), said in a statement. “The research and findings compiled here by our best scientists will serve as a springboard to our future legislative efforts to tackle this entirely solvable environmental challenge and better protect our marine ecosystems, fisheries, and coastal economies.”Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse (R.I.), the law’s primary Democratic sponsor, said, “I look forward to working with colleagues on both sides of the aisle to keep making progress cleaning up this harmful mess.”Christy Leavitt, plastics campaign director for advocacy group Oceana, said in a statement that the findings show the extent of U.S. responsibility for a global problem.“We can no longer ignore the United States’ role in the plastic pollution crisis, one of the biggest environmental threats facing our oceans and our planet today,” she said. “The finger-pointing stops now.”Spring said that the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the Environmental Protection Agency would be best positioned to develop a national strategy to curb plastic waste.“There’s more activity and testing of solutions at the state level as compared with other countries that are taking it at a national level,” she said. “Plastics and microplastics are ubiquitous in inland states too,” Spring said, referring to rivers, lakes and other waterways.“A lot of U.S. focus to date has been on the cleaning it up part,” said Spring. “There needs to be more attention to the creation of plastic.”The American Chemistry Council, a trade association, endorsed the idea of a national approach but said it opposed efforts to curtail the use of plastics in society.“Plastic is a valuable resource that should be kept in our economy and out of our environment,” said the group’s vice president of plastics, Joshua Baca, in a statement. “Unfortunately, the report also suggests restricting plastic production to reduce marine debris. This is misguided and would lead to supply chain disruptions.”The bipartisan oceans bill enacted last year also calls for a number of other analyses to be completed by the end of 2022, on topics ranging from the impacts of microfibers to derelict fishing gear.“You can’t just focus on one thing,” Spring said. “This really all has to be done with the end in mind, which is what is going to happen to this stuff when you’re finished with it.”