A new biomaterial created by methane-munching marine organisms can be molded into eyeglass frames or formed into leather-like sheets.Leather is a controversial material, and not just because cows have to die to produce it. Or because tanning leather requires toxic chemicals like chromium, which is sometimes dumped straight into local waterways. No, the worst part about leather, according to environmental activists, is that it’s a major contributor to climate change.Animal agriculture is estimated to be responsible for 14.5 percent of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions. Kering, the luxury fashion conglomerate that owns such storied leather-loving brands as Gucci and Yves Saint Laurent, said in its 2020 environmental report that the production and processing of leather is by far the biggest contributor to its carbon footprint. And when the Amazon was on fire in 2019, the blazes were blamed at least partially on cattle ranching operations, and several large brands including H&M and Timberland vowed to stop sourcing leather from the region.The alternatives available to the fashion industry, however—fossil-fuel-based polyurethane and PVC—leave something to be desired. All of the buzzy plant-based vegan leathers, whose manufacturers claim emit fewer greenhouse gases during production, are also mixed with synthetic petroleum products, making them more harmful than their “cruelty-free” marketing implies. With all the press around prototype products from Adidas and Stella McCartney, you would be forgiven for thinking you could already buy a lab-grown leather wallet or mushroom leather Stan Smith sneakers, but those materials are still struggling toward commercial viability.

Category Archives: Plastic Pollution Articles & News

Solving Bali’s rivers of trash

Article body copy

Practical Solutions for the Ocean’s Ailments

As scooters zip across a brick-walled bridge, about five kilometers from the Indian Ocean beaches of Bali, Indonesia, Made Bagiasa scythes young bamboo from the riverbank while Gary Bencheghib loops steel cable around a sturdy mango tree. In the river that divides the pair, hangs a metal grid topped with tubular PVC floats, a low-tech answer to the island’s very modern problem: plastic trash.

Bali’s tropical beaches and warm blue waters have drawn travelers since the 1920s. Even in the midst of the pandemic, nomads and expats still frequent the island’s surf camps, restaurants, and yoga studios; elsewhere, desolate budget hotels, desperate beach vendors, and deserted swimming pools, now breeding grounds for mosquitoes, pay testimony to COVID-19’s impact. Yet the Island of the Gods’ resilient brand of Hinduism endures. The rituals that set the rhythms of the year and the offerings that decorate almost every corner express devotion to harmony with god, nature, and humankind.

Despite the island’s profusion of sacred springs and water temples, and although river water is used to cleanse bodies before cremation, the waterways which have defined Bali’s landscapes for over 1,000 years are dumping grounds for trash. A 2021 New Year’s cleanup removed over 30 tonnes of marine litter from sweeping Kuta Beach and neighboring beaches. In 2018, a sperm whale washed ashore in an Indonesian national park, its stomach clogged with nearly six kilograms of plastic waste. Although the tourism ministry funds regular beach cleaning, plastic trash still pollutes both rivers and ocean.

Bali’s government has banned styrofoam, plastic straws, and single-use plastic bags, but the regulations are often ignored. In Indonesia, as in many lower-income countries, people often buy products such as shampoo in non-recyclable single-dose sachets, which strain budgets less than better value but more costly bottles; and no office or social gathering is complete without trays of Danone’s Aqua water, sold in single-serving plastic cups. (One hundred and fifteen plastic cups were found in the stomach of the beached sperm whale.)

Although some of the trash on Bali’s western beaches likely comes from the neighboring island of Java—barely two kilometers away at its closest point—the island’s rivers are a major contributor.

On the riverbank, Bagiasa hammers a steel stake into the cleared ground, anchoring the barrier. As we watch, a drifting Aqua bottle wends its way to the floats and spins, trapped, the first in an apparently never-ending flow of garbage down this sluggish, slender stream. Bencheghib’s organization, Sungai Watch, has now installed 100 such barriers on Bali’s rivers to trap waste before it reaches the ocean. (The word sungai means “river” in Indonesian.) Between November 2019 and July 2021, the barriers intercepted 650 tonnes of waste.

Bencheghib grew up on Bali after his family relocated from Paris, France. Horrified by the experience of surfing surrounded by floating plastic, he and his two siblings organized their first beach cleanup as teenagers in 2009 under the banner Make A Change.

In Bali, Indonesia, a team from the nonprofit organization Sungai Watch installs its 101st trash barrier. Photo courtesy of Sungai Watch

Bencheghib left the island to study filmmaking in New York City and began using this skill to raise awareness of the role of rivers in ocean pollution. In 2016, he and some friends sailed the Mississippi River on a raft made from 800 plastic bottles. The next year, alongside younger brother Sam, he paddled a kayak crafted from plastic waste down the Citarum, a waterway on Indonesia’s most populous island, Java, that some claim is the most polluted river in the world.

The stinking journey, through waters fetid with dead animals, effluent from textile factories, and plastic waste, intensified Bencheghib’s loathing of pollution. “That expedition changed our lives forever,” he says. “Instead of icebergs, you call them plastic bergs—and we were stuck in a bunch of plastic bergs. We couldn’t move. … We had to literally lift the kayaks up and walk along the side.”

Sungai Watch evolved from Make A Change’s organized beach and river cleanups, and Bencheghib worked with river barrier designers Plastic Fischer to place his first installation in November 2019. Although he had permission from the authorities, local villagers were initially suspicious, wanting to know who would take responsibility for clearing the trash the barrier collected.

Gary Bencheghib founded Sungai Watch, which installed its first river barrier in 2019. Here, Bencheghib holds up one element of a barrier—a float that holds a grid vertically in the water—at the installation of the organization’s 100th barrier. Photo courtesy of Sungai Watch

Bencheghib collected the waste himself at first, sorting it in his parents’ garage and sending it to a local recycler, but sponsorship from the World Wildlife Fund for Nature enabled him to secure a base for the project and hire his first team members. In August 2020, in the teeth of the pandemic, he began to source sponsorships from businesses, including Indonesia’s bestselling beer brand, Bintang. For an annual commitment starting from three million rupiah (US $210), organizations can have sections of a river barrier branded in their name.

Since then, the team has expanded rapidly, and now has 40 employees, all paid above the legal minimum wage for the area (around $205 per month). Five dedicated teams make daily rounds of the barriers to remove the waste. And that’s no small task: the first Sungai Watch installation intercepted 2,200 kilograms of plastic waste and 585 kilograms of organic waste in just 230 days. Sungai Watch barriers allow fish to pass through and can withstand rainy season floods that could raise the height of a river by three meters or more. For wider, deeper rivers, the team repurposes secondhand 19-liter plastic water drums to create a floating platform that collectors can walk along.

At their headquarters, down a sleepy road surrounded by rice fields, not far from the surfing beaches of Canggu, Sungai Watch employees process around two tonnes of river trash each day. Beside a traditional Indonesian wooden joglo house, screeching angle grinders flood the air with sparks as men assemble trash barriers and women clean, sort, and audit plastic waste, some destined for resale to recyclers. Murky water churns in homemade machines that wash the river mud off plastic bags for resale. Organic material, which spans the gamut from driftwood, Hindu offerings, and green coconut shells to rotten produce from the markets, is processed into compost in neat piles and baskets.

A Walker Barrier made of plastic drums holds back one day’s worth of trash. Photo courtesy of Sungai Watch

Despite the best efforts to reuse and recycle, some trash, including the noxious plastic bags of disposable diapers found on every single cleanup, still ends up in a landfill.

Besides handling river trash, Sungai Watch also works alongside volunteers and pays members of the local community to clean up illegal waste dumps: a 22-hectare mangrove site on a river estuary yielded 80 tonnes of plastic, some embedded a full meter deep in the soil. Increasingly, Bencheghib’s team is engaged in working with local authorities to help them manage their own waste.

Most of Sungai Watch’s staff originally worked in Bali’s tourist industry, which has been decimated since Indonesia closed its doors to foreign tourists in April 2020. Women who had worked laundering sheets and towels now sift through trash; Bagiasa, Sungai Watch’s head of cleanups, used to manage hordes of taxis at the island’s airport, which welcomed over six million foreign tourists in 2019. With Indonesia still mired in the COVID-19 crisis and Bali’s largest tourist markets, Australia and China, still effectively closed to overseas travel, it’s unlikely the island will see such numbers any time soon.

Nola Monica leads education and outreach projects for Sungai Watch. Photo courtesy of Sungai Watch

Nyoman Muditha, a slender, sinewy man with a gentle smile, worked as a cleaner on Kuta Beach from 1975 to 1998, rising before dawn to pick trash from the sands. Today he is a priest, performing Bali’s timeless rituals, and leads a local waste management project for Sungai Watch.

In his neat compound above a pristine river bend with a trash-free Sungai Watch barrier, chickens and cockerels scratch behind a wire fence while orchids and frangipani grow as gifts for friends. Muditha proudly displays water bottles crammed full of candy wrappers, rescued from the river: he is planning a campaign against these candies, which sit alongside flowers, snacks, incense, and, often, cigarettes in Bali’s handwoven offerings, and whose wrappers, like other street garbage, are swept into the rivers when rain falls.

In his neat garden, he is growing reedy shoots of vetiver grass in bamboo tubes, part of a Sungai Watch project to strengthen riverbanks and help purify the water. “The river should be sacred: it comes from Wisnu,” Muditha says, using the Balinese name for the Hindu deity Vishnu. “The flow of the water brings life for families and farmers. … In Bali, we need to keep the rivers clean and sacred.”

Faced with the paradox of a deeply religious society that nonetheless mistreats an environment theoretically held sacred, Muditha believes that older generations have failed to educate the youth. Older Balinese grew up when the population was both smaller and poorer, and used organic wrappings such as banana leaves that could be thrown into rivers without consequence, unlike today’s plastic packaging.

Yet waste management is also a structural problem, especially as collapsing local government budgets divert funds to the COVID-19 crisis and household incomes tumble. Waste collection is usually a paid service on Bali and, while freelance scavengers pick through household garbage for items that can be resold or reused, formal recycling options are relatively costly.

Sungai Watch relies on teams of community volunteers, such as these two men sorting plastic bottles retrieved from a trash barrier. Photo courtesy of Sungai Watch

Because there is little awareness of the damage that river trash can work on the ocean, education forms an ever-increasing part of Sungai Watch’s work. Nola Monica, who worked in villa rentals before joining the group, now leads education and outreach programs, presenting to village leaders and influential members of the community.

As an example of the need for education, she likes to tell the story of a woman who blithely returned to throwing trash in the river once she saw a barrier had been installed—she no longer felt guilty about disposing of her garbage, now that people were there to clean it up. The ultimate goal is not merely to intercept plastic trash before it hits the ocean but to change the mindset that put it there.

Bali’s main landfill is already at capacity and set to close, so waste management will be decentralized to the leaders of Bali’s 636 desa, an Indonesian word for “village” that also describes small local government units. Bencheghib aims to empower communities to manage their waste effectively, with solutions including composting, salvaging plastics for resale, and farming maggots on organic waste to be used (or sold) for chicken feed. The barriers, designed to be easy to move, will be transferred farther upstream as individual communities begin to manage their waste effectively.

Progress extends beyond the tonnes of trash saved from the ocean. Rivers, including Muditha’s, are visibly cleaner; the volumes of garbage caught by the barriers is decreasing, particularly in villages where Sungai Watch works closely with community leaders on education. In June 2021 alone, the team collected 506 kilograms of plastic cups and close to 10 times that weight in plastic bags. Volunteers are traveling from across the island to participate in cleanups.

But, even as he begins expanding his venture to Java, Bencheghib remains aware that hearts, minds, and habits take time to change. “Things go very slow here on Bali,” he says. “And that’s something that we tend to forget. In terms of changing mindsets, it’s not going to be one event, it’s going to be maybe 10 or 15 or 20 different events for that one person.”

Tips

Gather data. Sungai Watch uses a barcode scanner to identify and log plastic waste, a painstaking process which involves manually inputting 37,000 products from 10,000 brands. Bencheghib ultimately hopes the companies whose products are polluting the ocean will contribute to the cost of their disposal.

Highlight the economic benefits. Paying people fairly for their labor and generating both income and usable assets such as compost and maggots from trash shows the value of Sungai Watch’s work to communities.

Work with local community leaders on education. While most children go to school, the quality of education on Bali is low. Communicating that plastic trash harms marine ecosystems and does not degrade has been a key to success.

New federal legislation proposed to curb plastic pollution in national parks

A new federal bill proposed last week by U.S. Representative Mike Quigley (D-IL), the Reducing Waste in National Parks Act, aims to curb plastic waste and pollution in the U.S. National Park system. If passed, the legislation would reduce the use of disposable plastic products—including single-use beverage bottles, plastic bags, and plastic foodware—in many national park facilities across the country. Senator Jeff Merkley (D-OR) introduced a companion bill in the Senate. The United States is one of the largest plastic waste producers in the world. In 2018 alone, the country generated more than 35 million tons of plastic. While most of the plastic was sent to landfills, a significant amount ends up polluting our water and land—including our national parks.”National parks are bipartisan—everybody loves the national parks,” Quigley told EHN. As people continue to appreciate the beauty of national parks, he said, he hopes the bill educates and encourages them to reduce their plastic waste and protect the environment. Merkley told EHN, “Plastic pollution threatens our ability to live in healthy communities and to enjoy the beauty and majesty of our national parks, today and in the future.”Quigley said he hopes his bill will pass in the House this fall and advance to the Senate floor, adding, “we’re going to get very creative on how we move this thing forward.”

Reducing plastic sales and use

Representative Mike Quigley

The bill isn’t an outright ban on single-use plastic products. Instead, it directs the National Park Service to draft plans for reducing the sale and use of plastic products at the parks. To that end, the bill “is not one size fits all,” Quigley said, as each regional park director could tailor the waste-reduction effort for their region.

Scaling down plastic consumption and waste is not a new initiative for the National Park Service. In 2011, the Obama administration issued guidance that encouraged national parks across the country to stop selling plastic water bottles. Under the voluntary plastic ban, 23 out of 417 national parks—including Grand Canyon National Park and Zion National Park—restricted bottled water sales. As a result, Zion National Park in Utah saved 60,000 water bottles, or 5,000 pounds of plastic waste, by installing water stations and selling reusable water bottles, according to a statement from Quigley’s office following the announcement of the new bill.

The Trump administration overturned the Obama-era policy in 2017. The reversal came just weeks after the Senate confirmation of David Bernhardt, who was appointed the deputy secretary for the Department of Interior, the governing agency for the National Parks. A former lobbyist, Bernhardt had worked with Brownstein Hyatt Farber Schreck, the law firm that has represented Deer Park’s distributor Nestlé Waters.

A few months before the policy was overturned, the National Park Service published a report stating that the Obama administration’s guidance at participating national parks helped save 1.3–2.01 million disposable water bottles every year, reducing 73,000–111,000 pounds of plastic waste annually.

Politics of plastic

Quigley hopes by solidifying the plastic reduction rules into law, the Reducing Waste in National Parks Act will have a better chance of survival regardless of which party holds the White House.

“Rather than rely on the whims of whichever president happens to be in office,” Quigley said, “[the bill] would codify this guidance and ensure that future administrations can’t reverse it.” Before this bill, Quigley tried to introduce similar versions of the act in 2017 and 2019, but both died in Congress.

The National Park Service declined to comment. “NPS does not comment on proposed legislation until we have testified on the legislation (if asked to do so),” the agency’s spokesperson told EHN. Meanwhile, environmental advocacy groups have so far applauded this bill.

“On average, the park service manages nearly 70 million pounds of waste annually, including plastics that pollute lands and waterways and harm our fragile ocean ecosystems,” John Garder of the National Parks Conservation Association, an environmental group for national parks throughout the country, told EHN. “The National Park Service and all of us must continue to examine ways to reduce waste, and we applaud the effort of Sen. Merkley and Rep. Quigley to address this important issue.”

Banner photo: Yellowstone National Park visitors wait for Old Faithful. (Credit: Nick Amoscato/flickr)

Exxon Mobil to build new plastic waste recycling facility in Baytown, Texas

Exxon Mobil is set to build its first large-scale plastic waste advanced recycling facility in Baytown with initial capacity to recycle 30,000 metric tons per year, the company announced Monday.The Irving-based oil and gas giant said the facility is the first step in its plans to build around 500,000 metric tons of recycling capacity globally over the next five years. The facility in Baytown, located about 26 miles east of Houston, is expected to begin operations by the end of next year.Exxon didn’t indicate how much the new recycling plant will cost.A smaller, temporary facility is already working in Baytown, producing materials that can be used to make plastic and other products, Exxon said. The trial has recycled more than 1,000 metric tons of waste to date, equivalent to 200 million grocery bags.“We’ve proven our proprietary advanced recycling technology in Baytown, and we’re scaling up operations to supply certified circular polymers by year-end,” said Exxon Mobil Chemical Co. president Karen McKee. “Availability of reliable advanced recycling capacity will play an important role in helping address plastic waste in the environment, and we are evaluating wide-scale deployment in other locations around the world.”Global demand for consumer plastics is growing, pushing many in the plastics industry to consider the need for a circular plastics economy. By 2050, global waste plastics will increase by between 170 million and 190 million metric tons to more than 425 million metric tons, according to an analysis by research firm IHS Markit.Waste created in the plastics industry could be limited, the report said, if the more than $300 billion of capital spending set aside for new plastics production was instead redirected to recycling processing.“Our analysis indicates that the situation is likely to become urgent,” IHS Markit vice president Anthony Palmer said. “At the heart of the matter is that the widespread benefits associated with the use of plastics contrast sharply with the way the world manages its end-of-life disposal — the so-called ‘Plastics Dilemma.’ ”Just 20 petrochemical companies are responsible for over half of all single-use plastic waste, according to the Plastic Waste Makers Index published by the Minderoo Foundation. Exxon is the biggest offender, contributing 5.9 million metric tons to global plastic waste.The new Baytown facility is just one of Exxon’s plastic recycling endeavors.The company is working with London-based Plastic Energy to build an advanced recycling plant in France that’s expected to process 25,000 metric tons of plastic waste annually. The France facility, which has the potential to expand to up to 33,000 metric tons of capacity, will become operational in 2023.Exxon said it is also looking at recycling plant sites in the Netherlands, Canada, Singapore and the U.S. Gulf Coast.

Photos show Manila Bay mangroves ‘choking’ in plastic pollution

PhilippinesPhotos show Manila Bay mangroves ‘choking’ in plastic pollutionThe Navotas mudflats are among the last of their kind and act as a crucial feeding ground for migratory birds, but they are being buried in plastic Rebecca Ratcliffe, south-east Asia correspondentMon 4 Oct 2021 20.13 EDTLast modified on Tue 5 Oct 2021 15.22 EDTThere are stray, abandoned flip flops, old foil food wrappers, crumpled plastic bags, and discarded water bottles. The Navotas mudflats and mangroves in Manila Bay are buried in a thick layer of rubbish.It is “almost choking the mangrove roots,” Diuvs de Jesus, a marine biologist in the Philippines who photographed the area on a recent visit, said.The wetlands are of huge environmental significance. They provide a crucial feeding ground for migratory birds, offer protection against floodwater and help tackle climate change by absorbing far greater levels of carbon dioxide than mountain forests.The plastic pollution, though, could devastate the area. Mangroves have special roots, known as pneumatophores, “sort of like a snorkel that helps them breathe in when sea water rises,” says Janina Castro, member of the Wild Bird Club of the Philippines and advocate for wetland conservation. Plastic risks suffocating pneumatophores, weakening, and potentially killing the trees.’The odour of burning wakes us’: inside the Philippines’ Plastic CityRead moreThe mudflats and mangroves are already one of the last of their kind in Manila Bay, an area that was once lined with lush, green shrubs and trees. Manila is thought to have been named after the Nilad, a stalky rice plant that grows white flowers, and which once thrived along the coastline. At the end of the 19th century, there were up to 54,000 hectares of mangrove wetlands along the bay, according to an estimate cited by Pemsea, a regional, marine protection partnership coordinated by the United Nations. By 1995 this had fallen to fewer than 800 hectares.Today, Manila, one of the most densely populated cities in the world, is more likely to be associated with traffic jams than flourishing mangroves.“If only we banned single-use plastics, that will greatly reduce the litter,” De Jesus said. He worries also about the looming threat of reclamation – where coastlines are extended outwards as rock, cement and earth are used to build new land in the sea.The Navotas mangroves and mudflats are vital to the survival of migratory birds that visit the Philippines as part of the east Asian-Australasian flyway – a route that stretches from Arctic Russia and North America down to Australia and New Zealand.A number of endangered birds have been spotted feeding and resting in the wetlands, including the black-faced spoonbill, the far eastern curlew, and the great knot. The critically endangered Christmas Island frigatebird was also recently seen flying low over Navotas, Castro says.Environmentalists fear plastic pollution could ultimately harm such species. It breaks down into microplastics, which can be eaten by fish and shellfish – and, consequently, also be ingested by birds. It can also lead to an accumulation of toxic chemicals, and act as a vector for disease, threatening birds and their prey, Castro said.“A number of these species currently have conservation efforts happening in other countries, but these efforts need to be mirrored in all of the staging sites including the Philippines,” Castro said.There is a misconception that mudflats are not as valuable or aesthetically pleasing as other types of wetlands, Castro said. But they play an important role in tourism, providing livelihoods and offering wave protection. “Educating the public about these benefits is critical for its survival,” she said.TopicsPhilippinesAsia PacificPollutionfeaturesReuse this content

India to ban single-use plastics but experts say more must be done

Following the Indian government’s announcement banning various low-utility plastics, experts outline a list of structural issues that need to be addressed for the ban to be effective.

Research and development into alternatives along with guidelines for their efficient use are needed.

A lack of quality recycling and waste segregation also need to be addressed to improve the percentage of plastic that is recycled.

A cyclist uses a plastic sheet to protect himself from rain, at sector 27, on August 1, 2021 in Noida, India.

Sunil Ghosh | Hindustan Times | Getty Images

India will ban most single-use plastics by next year as part of its efforts to reduce pollution — but experts say the move is only a first step to mitigate the environmental impact.

India’s central government announced the ban in August this year, following its 2019 resolution to address plastic pollution in the country. The ban on most single-use plastics will take effect from July 1, 2022.

Enforcement is key for the ban to be effective, environmental activists told CNBC. New Delhi also needs to address important structural issues such as policies to regulate the use of plastic alternatives, improve recycling and have better waste segregation management, they said.

Single-use plastics refer to disposable items like grocery bags, food packaging, bottles and straws that are used only once before they are thrown away, or sometimes recycled.

“They have to strengthen their systems in the ground to ensure compliance, ensure that there is an enforcement of this notification across the industry and across various stakeholders,” Swati Singh Sambyal, a New Delhi-based independent waste management expert told CNBC.

Why plastics?

As plastic is cheap, lightweight and easy to produce, it has led to a production boom over the last century, and the trend is expected to continue in the coming decades, according to the United Nations.

But countries are now struggling with managing the amount of plastic waste they have generated.

About 60% of plastic waste in India is collected — that means the remaining 40% or 10,376 tons remain uncollected, according to Anoop Srivastava, director of Foundation for Campaign Against Plastic Pollution, a non-profit organization advocating for policy changes to tackle plastic waste in India.

Independent waste-pickers typically collect plastic waste from households or landfills to sell them at recycling centers or plastic manufacturers for a small fee.

However, a lot of the plastics used in India have low economic value and are not collected for recycling, according to Suneel Pandey, director of environment and waste management at The Energy and Resources Institute (Teri) in New Delhi.

In turn, they become a common source of air and water pollution, he told CNBC.

Banning plastics is not enough

Countries, including India, are taking steps to reduce plastic use by promoting the use of biodegradable alternatives that are relatively less harmful to the environment.

For example, food vendors, restaurant chains and some local businesses have started adopting biodegradable cutlery and cloth or paper bags.

However, there is currently “no guideline in place for alternatives to plastics,” Sambyal said.

That could be a problem when the plastic ban takes effect.

A machine picking up waste in the pile of garbage at the Ghazipur land fill site where city’s daily waste has been dumped for last 35 years. The machine separates waste into three parts first stone and heavy concrete material second plastic, polythene and third is fertilizer and soils.

Pradeep Gaur | SOPA Images | LightRocket | Getty Images

Sambyal said clear rules are needed to promote alternative options, which are expected to become commonplace in future.

The new rules also lack guidelines on recycling.

Though around 60% of India’s plastic waste is recycled, experts worry that too much of it is due to “downcycling.” That refers to a process where high-quality plastics are recycled into new plastics of lower quality — such as plastic bottles being turned to polyester for clothing.

“Downcycling decreases the life of the plastic. In its normal course, plastic can be recycled seven to eight times before it goes to an incineration plant … but if you downcycle, after one or two lives itself, it will have to be disposed,” said Pandey from Teri.

In India’s state of Maharashtra, people are seen carrying bags of other materials, mostly cotton for their daily routine and shopping on June 24, 2018 in Pune, India.

Rahul Raut | Hindustan Times | Getty Images

Tackling waste segregation is also essential.

If general waste and biodegradable cutlery are disposed together, it defeats the purpose of using plastic alternatives, according to Sambyal.

“It is high time that source segregation of domestic waste is implemented vigorously,” said Foundation for Campaign Against Plastic Pollution’s Srivastava, referring to waste management laws that are in place, but not followed closely.

Way forward

Environmentalists generally agree that the ban is not sufficient on its own and needs to be supported by other initiatives and government regulations.

The amount of plastic that is collected and recycled needs to be improved. That comes from regulating manufacturers and asking them to clearly mark the type of plastic used in a product, so it can be recycled appropriately, said Pandey.

A women rag picker collecting plastic bottle and other plastic materials in a boat from the bank of Brahmaputra River in Guwahati, Assam, India on Monday, October 29, 2018.

David Talukdar | NurPhoto | Getty Images

In addition to improving recyclability, investment in research and development for alternatives should also be a priority.

Pandey explained that India is a big, price-sensitive market where plastic alternatives could be produced in bulk and sold at affordable prices.

Several Indian states introduced various restrictions on plastic bags and cutleries in the past, but most of them were not enforced strictly.

Still, the latest ban is a big step toward India’s fight against landfill, marine and air pollution — and is in line with its broader environmental agenda, according to the experts.

In March, India said it was on track to meet its Paris agreement climate change targets, and added that it has voluntarily committed to reducing greenhouse gas emission intensity of its GDP by 33% to 35% by 2030.

WATCH LIVEWATCH IN THE APP

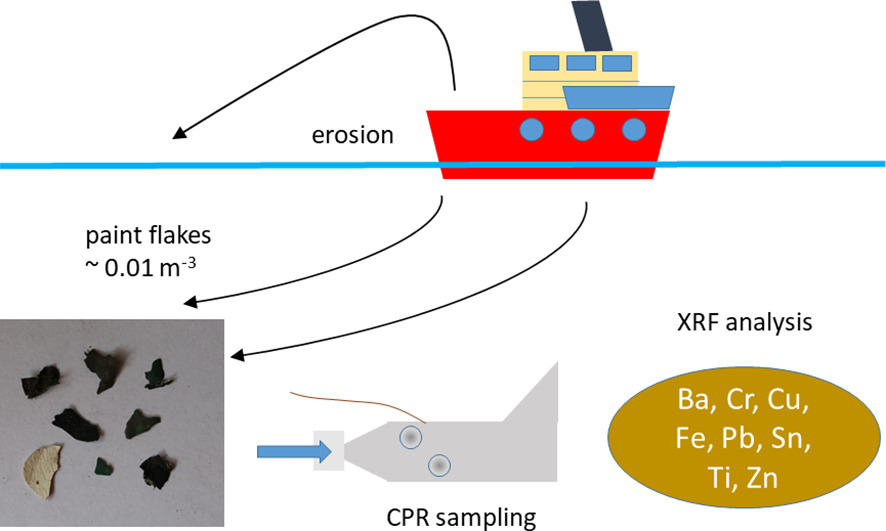

Paint flakes most abundant microplastic particles after fibers

A new report suggests that paint flakes could be one of the most abundant type of microplastic particles found in the ocean. As with other types of microplastics, the effect on marine life and the ocean are not yet fully understood.

The study, published in Science of the Total Environment and carried out by the University of Plymouth and the Marine Biological Association (MBA), conducted several surveys across the North Atlantic Ocean and estimated through more than 3,600 collected samples that each cubic metre of seawater contained an average of 0.01 paint flakes. This finding suggests that paint flakes are the second largest type of microplastic particles found in the ocean after microplastic fibres which has a concentration of around 0.16 particles per cubic metre.

The study further estimated that some of the paint flakes also had high quantities of lead, iron as well as copper due to them having antifouling or anti-corrosive properties. The researchers argued that this could further pose a threat to the ocean and the species living in it if they ingest the particles.

“Paint particles have often been an overlooked component of marine microplastics but this study shows that they are relatively abundant in the ocean. The presence of toxic metals like lead and copper pose additional risks to wildlife,” said Dr Andrew Turner, the study’s lead author and associate professor in environmental sciences at the University of Plymouth.

Therefore, paint flakes can be considered the most abundant type of microplastic in the ocean after fibres. And this development needs closer scientific attention as the full effect of the metallic additives on the ocean and its species is not yet fully understood.

For more from our Ocean Newsroom, click here.

Photography courtesy of Unsplash, graphical abstract found here.

Wilmington, NC, partners with groups, businesses to cut plastic waste

Tricia Monteleone, left, vice president of Plastic Ocean Project Inc., and Bonnie Monteleone, the group’s executive director, pose during an event in September at Waterline Brewing Co. in Wilmington. Contributed photo by Moe Saur

Wilmington put in place a sustainability program in 2012 that recently has been trying to combat plastic pollution – especially plastic bags — through education and outreach, with the help of a state grant and partnerships with nonprofit organizations.

The sustainability program aims to efficiently manage energy, water and waste, “while cultivating a culture of environmental stewardship throughout city operations to reduce our environmental footprint. We strive to implement fiscally and environmentally sound projects to preserve the quality of life of our community and resources,” according to the city.

Part of the outreach included having the city council approve in September a resolution to reduce plastic waste and support Ocean Friendly Establishments, a nonprofit initiative that encourages businesses and nonprofits to reduce single-use plastics.

David Ingram, Wilmington’s sustainability project manager, who has been in this role since 2015, said in an interview that the resolution ties in nicely with his department’s outreach work funded through a state grant from the 2020 Community Waste Reduction and Recycling Grant Program.

The city was awarded $16,917 with a $3,383 match requirement, totaling $20,300 toward the effort. The grant, which was put in place to help local governments in expanding, improving and implementing waste reduction and recycling programs, is administered by the North Carolina Division of Environmental Assistance and Customer Service through the Solid Waste Management Outreach Program, according to city officials.

City officials apply for this grant each year. This year, they pitched building the city’s recycling program with a focus on increasing public awareness of waste reduction and recycling and supporting the statewide Recycle Right NC campaign as well as promote the “Mayor’s Plastic Bag Challenge,” an effort to reduce single-use plastic bag usage.

“This year, the focus of that grant was really just a lot of outreach and education in regards to not only Recycling Right, but also promoting the use of reusable bags to help eliminate the use of single-use plastic bags,” Ingram said.

Ingram said the city had used the grant to take numerous steps to educate residents and help them understand what can be recycled, including Recycle Right NC materials. “We really tried to kind of simplify and make it more streamlined,” he said.

The city program also purchased reusable bags to hand out and provided some to the Plastic Ocean Project to distribute at their recent events, Ingram added.

“I would say to this particular grant, the education outreach efforts will be ongoing, and we have quite a few more reusable bags to distribute. We have a lot of messaging just in regard to Recycling Right,” he said. “Going forward, we hope to collaborate on some other events as well just to continue that messaging.”

Ocean Friendly Establishments is an initiative of the Plastic Ocean Project, which aims to educate the public and help address the global plastic pollution problem.

Plastic Ocean Project Executive Director Bonnie Monteleone told Coastal Review that it didn’t take long to convince the city council to approve a resolution of support for the effort, but COVID-19 delayed progress for more than a year.

“As the saying goes, it takes a village,” Monteleone said, adding Ingram played a major role in bringing the resolution to the city council. Numerous Wilmington Ocean Friendly Establishments committee members joined in the effort along with help from the North Carolina Aquarium at Fort Fisher.

Monteleone noted that the bag campaign to encourage using reusable bags is in line with the city council’s resolution and with Plastic Ocean Project efforts in general.

“We are in the process of designing a ‘Got your bag’ logo that will be displayed in parking lots and billboards,” Monteleone said. Plastic Ocean Projects is also connecting with grocery stores to provide educational materials and the reusable bags from the city. “We hope to initiate the campaign mid-November that will focus on a positive message.”

Monteleone explained that the Ocean Friendly Establishment program began with just addressing the use of straws, encouraging restaurants to only give them out upon request. “It has now grown into a five-star program. This a perfect example of how one small effort can turn into a movement. We hope the bag campaign will do the same.”

Ocean Friendly Establishments is the brainchild of Ginger Taylor, a volunteer for the Wrightsville Beach Sea Turtle program, who saw the need for a solution to plastic straw litter, Monteleone said. Taylor was troubled by the number of straws she picked up in Wrightsville Beach while walking the strand identifying turtle tracks and pitched her idea at a North Carolina Marine Debris Symposium, an annual symposium featuring presentations by environmental and educational groups on different efforts to tackle marine debris.

Through the work of the Plastic Ocean Project, the North Carolina Aquarium at Fort Fisher and other organizations including the North Carolina Aquarium’s Jeanette’s Pier and nonprofits such as Keep Brunswick County Beautiful, the North Carolina Coastal Federation and Crystal Coast Riverkeepers, Ocean Friendly Establishments now has more than 200 establishments, including businesses, restaurants, breweries and nonprofits. “It’s a great example of the power of one and our very caring communities,” she said.

What makes the Ocean Friendly Establishments program successful is the numerous volunteers that make up many committees along the coast. “They are truly the driving force behind the success of this program as well as the resolutions,” she said.

A self-regulating, community-based certification program, Ocean Friendly Establishments has its own website where volunteers can join committees and businesses can apply for certification.

“It all comes down to using less plastic. Nature did not design plastic and therefore does not know what to do with it, hence it persists in the environment indefinitely. Because it can persist for decades and in some cases centuries, it can wreak havoc on the natural world and sadly is. The solution to plastic pollution is to reduce. If we don’t use it, we can’t lose it,” she said.

Why is plastic a problem?

Ingram told the city council in September that while the city has a long history of being a steward of the coastal environment, “We do recognize that plastic film and single-use plastics represent a contamination in our local environment, as well as our waste stream.”

Ingram said that plastic bags, while they are recyclable, tend to be placed in either curbside recycling or in locations that are not the proper place to drop these items off. When that happens, the bags impede the recycling process at many of the materials recovery facilities. The bags clog the system and force the machinery to be shut down, leading to delays and increased costs.

“This plastic film and bags, as well as straws, represent an enormous impact to our local waterways, when they don’t make it into our recycling or waste stream,” Ingram said. “They break down into small fragments that not only float on the surface of our waters but actually can sink down to the bottom and be very difficult to ever remove from the environment.”

Monteleone said Americans use more than 1 billion plastic bags a year – about 365 bags per person — which in total equals about 12 million barrels of oil.

While these bags can be recycled, many are not and chemicals leech out from the plastic bags and are starting to affect animals. Organisms that convert carbon dioxide into oxygen are compromised because of plastics. “These are getting lost in the environment and wreaking havoc on our marine life. “

About 70% of the Earth’s surface is covered in water and anything that ends up in the environment has the potential of getting into storm drains and into rivers, which lead to the ocean.

Newsom signs laws banning 'forever chemicals' in children's products, food packaging

California Gov. Gavin NewsomGavin NewsomOvernight Energy & Environment: White House to restore parts of Trump-lifted environmental protections law Equilibrium/Sustainability — Presented by The American Petroleum Institute — NASA to unleash ‘planetary defense’ tech against asteroid Schwarzenegger: Jan. 6 shows what happens ‘when people are being lied to about the elections’ MORE (D) signed two laws on Tuesday banning the use of toxic “forever chemicals” in children’s products and disposable food packaging, as well as a package of bills to overhaul the state’s recycling operations, his office announced that evening.“California’s hallmark is solving problems through innovation, and we’re harnessing that spirit to reduce the waste filling our landfills and generating harmful pollutants driving the climate crisis,” Newsom said in a press statement.The pollutants driving the first two laws are perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), a group of toxic compounds linked to kidney, liver, immunological, developmental and reproductive issues. These so-called forever chemicals are most known for contaminating waterways via firefighting foam, but they are also key ingredients in an array of household products like nonstick pans, toys, makeup, fast-food containers and waterproof apparel.ADVERTISEMENTOne of the laws, introduced by Assemblywoman Laura Friedman (D), prohibits the use of PFAS in children’s products, such as car seats and cribs, beginning on July 1, 2023, according to the governor’s office.“As a mother, it’s hard for me to think of a greater priority than the safety and well-being of my child,” said Friedman in a news release from the Environmental Working Group (EWG). “PFAS have been linked to serious health problems, including hormone disruption, kidney and liver damage, thyroid disease and immune system disruption.“This new law ends the use of PFAS in products meant for our children,” she added.Bill Allayaud, EWG’s director of California government affairs, praised Newsom “for giving parents confidence that the products they buy for their children are free from toxic PFAS.”“It’s heartening that for this legislation, the chemical industry joined consumer advocates to create a reasonable solution, as public awareness increases of the health risks posed by PFAS exposure,” he said in a statement.ADVERTISEMENTBecause PFAS coating on infant car seats and bedding wear off with time, the toxins can get into dust that children might inhale, according to the EWG.The second PFAS-related law, proposed by Assemblyman Philip Ting (D), bans intentionally added PFAS from food packaging and requires cookware manufacturers to disclose the presence of PFAS and other chemicals on products and labels online — beginning on January 1, 2023.“PFAS chemicals have been a hidden threat to our health for far too long,” Ting said in a second EWG news release. “I applaud the governor for signing my bill, which allows us to target, as well as limit, some of the harmful toxins coming into contact with our food.”Despite the widely recognized risks of PFAS exposure, the Environmental Protection Agency has only established “health advisory levels” for the two most well-known compounds rather than regulate the more than 5,000 types of PFAS. States like California have therefore taken to enacting bits and pieces of legislation on their own. Although the House passed a bill in July that would require the EPA to set standards, companion legislation has yet to reach the Senate.“This law adds momentum to the fight against nonessential uses of PFAS,” David Andrews, a senior scientist at EWG, said in a statement. “California has joined the effort to protect Americans from the entire family of toxic forever chemicals.”ADVERTISEMENTAs far as recycling is concerned, Newsom signed a law banning the use of misleading recycling labels, as well as legislation designed to raise consumer awareness and industry accountability. The recycling bills serve to complement a $270 million portion of the state budget that will go toward modernizing recycling systems and promoting a circular economy, according to his office.Other measures in the recycling package include provisions to discourage the export of plastic that becomes waste, more flexibility for operations at beverage container recycling centers and labeling requirements to ensure that products designated as “compostable” are truly compostable.“With today’s action and bold investments to transform our recycling systems, the state continues to lead the way to a more sustainable and resilient future for the planet and all our communities,” Newsom said.

Greenland looks for ways to bust ghost fishing gear

Fishing gear continues to do what it is designed to do, even after it is discarded at sea. Here, fishing gear is wrapped around a whale fluke. (Naalakkersuisut)

So-called “ghost” fishing gear may be robbing the seas around Greenland of more than three tons of fish each year, at a total economic cost that amounts to 5 percent of the value of the country’s most important industry, an estimate by the research and environment ministry reckons.

Ghost gear — commercial fishing nets that are either lost or intentionally discarded at sea — poses a problem in Greenland and elsewhere not just because it continues to trap fish for as long as three years once it is in the water, but also because it can trap other animals. In addition, as the nets age, they break down into increasingly smaller plastic particles that are consumed by all manner of marine organisms, eventually making it into humans.

Half of the plastic that washes up on Greenland’s shores each year stems from the fishing industry. While this has alerted the public and lawmakers to the problem, its true extent is unknown, according to the ministry. That’s because most of the gear remains at sea — where fishermen say it ensnares other nets and fishing lines, which in many cases must be cut free, only adding to the problem.

[West Greenland’s plastic litter mostly comes from local sources, study finds]

There is no figure for the amount of fishing gear Greenland’s 1.2 billion kroner ($190 million) fishing industry loses each year, but there is evidence to suggest that it is significant. Using information from fishermen themselves as well as from regional authorities, the ministry calculates that, within three nautical miles of the coast, there may be a total 14,000 square kilometers (an area the size of two million soccer fields) where there is a moderate to high likelihood of finding ghost gear.

The biggest collections of gear may be in 19 hotspots where gear loss is most common, due to the type and intensity of fishing carried out in these areas, combined with conditions on the seabed that can result in nets getting caught or torn.

In recently published recommendations for preventing ghost gear, the ministry suggests starting clean-up efforts in three of the most heavily fished areas, covering a total of 420 square kilometers, where the concentration of ghost gear is likely to be greatest.

[Scientist calls for international cooperation to reduce marine plastics]

Such an effort would involve a ship collecting nets around the clock for a 12-week period each year, and take four to five years to complete, eventually costing 30 million kroner — about half of what the industry loses each year as a result of ghost gear.

The cost of successive cleanups would be lower, but factors such as weather, the distance to port facilities, sea ice and the presence of icebergs would still make it considerably more expensive to remove ghost gear from the waters off Greenland than those elsewhere. The proposed Greenland cleanup would probably cost twice as much as a similar, highly effective, Norwegian program.

While continued cleanups at land and sea will be necessary, the recommendations suggest that the amount of ghost gear can be reduced through financial measures — such as a surcharge or deposit — or by requiring that a net can be traced back to the vessel that lost it.

Such measures have worked in Iceland, where the revenue it generates goes to pay for cleaning collecting ghost gear at sea. The ministry warns, however, that most measures would entail a cost for fishermen, and that if the value of fishing gear increases, it is more likely to be stolen.