Limerick-based ISHKA Irish Spring Water is on course to dramatically reduce plastic pollution through the use of tethered caps and will trial the caps across its spring water range from this week – three years before EU rules making it compulsory for plastic bottle tops to remain connected to bottles. Pictured are Denis Sutton, Director, and Mark Taylor, Head of Operations, ISHKA Irish Spring Water.

LIMERICK-based ISHKA Irish Spring Water is on course to dramatically reduce plastic pollution through the use of tethered caps, becoming the first bottled water company in Ireland to do so.

The company will trial the caps across its spring water range from this week – three years before EU rules make it compulsory for plastic bottle tops to remain connected to bottles.Bottle tops account for 10% of plastic litter found on European beaches and the EU’s Single-Use Plastic Directive includes a provision to ensure they are recycled together with the rest of the bottle.

Sign up for the weekly Limerick Post newsletter

Later this year, all ISHKA 500ml spring water bottles will have their caps fully attached to the bottle, making them extremely difficult to remove.

“ISHKA is determined to do all we can as a business to drive the necessary change in consumer behaviour to help solve our global waste problem and protect marine life,” said Denis Sutton, Director of ISHKA Irish Spring Water.

“Due to their current design and size, caps are much more likely to be littered – and while this may seem like a small problem, they are one of the top five most commonly found items of litter on beaches worldwide.

“A simple design change that keeps caps attached to bottles means they are much more likely to be recycled with the bottle, hence our early move to launch tethered caps well ahead of the EU Directive deadline.”

Recent research from ISHKA, through iReach, shows many consumers are embracing the green message, with half of all respondents saying the type of water they buy is influenced by whether bottles can be recycled after use.

A separate study by PricewaterhouseCoopers estimates that around 1,350 bottling lines EU-wide will need to be prepared to handle tethered caps.

“As a company, we’re continually committed to product innovation and differentiation with sustainability at the core,” said Mark Taylor, Head of Operations, ISHKA Irish Spring Water.

“Over the summer we invested substantially in tooling up our machines and adapting our production lines so that our 500ml bottles can be fully recycled from bottle through to the cap. And from early next year, our full range of bottle sizes will have tethered caps.”

Based in Ballyneety in Limerick, ISHKA Irish Spring Water lays claim to being Ireland’s freshest spring water as it is bottled straight from five certified wells, untouched by human contact and not stored prior to bottling.

Category Archives: News

Waitrose announces further cutback on single-use plastic bags

Waitrose Waitrose announces further cutback on single-use plastic bags Supermarket says it aims to remove 40m a year from deliveries and in-store collections PA Media Sun 12 Sep 2021 20.00 EDT Waitrose is aiming to eliminate 40m single-use plastic bags a year by removing them from deliveries and in-store collections. “Bags for life”, which cost …

Continue reading “Waitrose announces further cutback on single-use plastic bags”

California aims to ban recycling symbols on things that aren’t recyclable

The well-known three-arrows symbol doesn’t necessarily mean that a product is actually recyclable. A new bill would limit the products allowed to feature the mark.The triangular “chasing arrows” recycling symbol is everywhere: On disposable cups. On shower curtains. On children’s toys.What a lot of shoppers might not know is that any product can display the sign, even if it isn’t recyclable. It’s false advertising, critics say, and as a result, countless tons of non-recyclable garbage are thrown in the recycling bin each year, choking the recycling system.Late on Wednesday, California took steps toward becoming the first state to change that. A bill passed by the state’s assembly would ban companies from using the arrows symbol unless they can prove the material is in fact recycled in most California communities, and is used to make new products.“It’s a basic truth-in-advertising concept,” said California State Senator Ben Allen, a Democrat and the bill’s lead sponsor. “We have a lot of people who are dutifully putting materials into the recycling bins that have the recycling symbols on them, thinking that they’re going to be recycled, but actually, they’re heading straight to the landfill,” he said.The measure, which is expected to clear the State Senate later this week and be signed into law by Gov. Gavin Newsom, is part of a nascent effort across the country to fix a recycling system that has long been broken.Though materials like paper or metals are widely recycled, less than 10 percent of plastic consumed in the United States is recycled, according to the most recent estimates by the Environmental Protection Agency. Instead, most plastic is incinerated or dumped in landfills, with the exception of some types of resins, like the kind used for bottled water or soda.For years, the United States also shipped much of its plastic waste overseas, choking local rivers and streams. A global convention now bans most trade in plastic waste, though U.S. waste exports have not completely ceased.This summer, Maine and Oregon passed laws overhauling their states’ recycling systems by requiring corporations to pay for the cost of recycling their packaging. In Oregon, the law included plans to establish a task force that would evaluate “misleading or confusing claims” related to recycling. Legislation is pending in New York that would, among other things, ban products from displaying misleading claims.In the past year, a number of environmental organizations have filed lawsuits seeking to combat misleading claims of recyclability by major corporations. Environmental groups have also criticized plans by the oil and gas industry to expand its production of petrochemicals, which are the main building blocks of plastic, because the process is highly polluting and creates new demand for fossil fuels.The recycling symbol is “subconsciously telling the people buying things, ‘You’re environmentally friendly,’” said Heidi Sanborn, the executive director of the National Stewardship Action Council, which advocates corporations to shoulder more responsibility for recycling their products.“Nobody should be able to lie to the public,” she said.In California, the bill won the backing of a coalition of environmental groups, local governments, waste haulers and recyclers. Recycling companies say the move will help them cut down on the non-recyclable trash thrown in recycling bins that needs to be transported, sorted and sent to the landfill.Pete Keller, vice president of recycling and sustainability at Republic Services, one of the country’s largest waste and recycling companies, said in an interview that more than a fifth of the material his company processes nationwide is non-recyclable garbage. That means that even on its best day, Republic is running at only 80 percent efficiency, processing materials it shouldn’t be processing, he said.Some of the most common forms of non-recyclable trash marring operations at Republic’s 70 facilities across the United States, which processes six million tons of curbside recycling a year: snack pouches, plastic film, grocery bags and packing material. Plastic bags, in particular, can’t be recycled in most curbside recycling programs and notoriously gum up recycling machines.“There are a lot of products in the marketplace today that have the chasing arrows that shouldn’t” Mr. Keller said. “There aren’t really any true end markets, or any real way to recover and ultimately recycle those materials in curbside programs.”The plastics and packaging industry has opposed the bill, saying it would create more confusion for consumers, not less. An industry memo circulated among California lawmakers urges them to oppose the bill unless it is amended, arguing it “would create a new definition of recyclability with unworkable criteria for complex products and single use packaging.”The letter was signed by industry heavyweights like the American Chemistry Council, the Plastics Industry Association and Ameripen, a packaging industry group. California should wait for Washington to come up with nationwide labeling standards, the groups said.In discussions over the bill, opposition industry groups also said that if a product is deemed non-recyclable, companies won’t invest in technologies to recycle it. Supporters of the bill say the opposite would be true: Tougher rules would incentivize manufacturers to make their products truly recyclable by investing in new packaging, for example.Dan Felton, Ameripen’s executive director, expressed concerns that the bill would actually reduce recycling rates. The bill “could have the unintended consequence of sending more packaging material to landfills at the very time when California needs to boost recycling,” he wrote in an email.The American Chemistry Council referred questions to Ameripen. The Plastics Industry Association, which represents plastic manufacturers, warned that the bill would determine a slew of products to be unrecyclable and therefore would be landfilled. (Supporters of the bill point out those products are landfilled anyway, despite displaying the recycling symbol.)Environmental groups said that strengthening government oversight is critical. “It’s the wild, wild West of product claims and labeling with no sheriff in town,” Jan Dell, an engineer and founder of The Last Beach Cleanup, an environmental organization, wrote in an email.The bill would make it a crime for corporations to use the chasing arrows recycling symbol on any product or packaging that hasn’t met the state’s recycling criteria. Products would be considered recyclable if CalRecycle, the state’s recycling department, determines they have a viable end market and meet certain design criteria, including not using toxic chemicals.In addition to plastics, the bill covers all consumer goods and packaging sold in the state, excluding some products that are already covered by existing recycling laws, such as beverage containers and certain kinds of batteries. Through its environmental advertising laws, California already prohibits companies from using words like “recyclable” or “biodegradable” without supporting evidence.

Goa's Sal River contaminated by microplastics; fish, shellfish laced with polymers

Representational image(IANS)Water, sediments and biota (animal and plant life) in the Sal river—a major water body in South Goa—are contaminated with microplastics (MPs), the most common being black MPs which are caused by the abrasion of motor vehicle tyres on road surfaces, a study has revealed.The first such study conducted in the Sal river by scientists and researchers attached to the National Institute of Oceanography and Academy of Scientific and Innovative Research, both in Goa, and the School of Civil Engineering, Vellore Institute of Technology (VIT), has also revealed the presence of three major polymers: polyacrylamide, a water-soluble synthetic linked to the mining industry; ethylene-vinyl alcohol used in packaging; and polyacetylene, an electrical conductivity agent.Among the biota, the study covered the examination of samples of shellfish, finfish, clams and oysters.Fringed by fast-paced real estate development, the Sal river, whose course runs through the coastal areas of the district before meeting the Arabian Sea by the picturesque Betul beach, is also a major source of livelihood for the local fisherfolk community.”Interestingly, MPs found in all the three matrices, water, sediment and biota from the Sal estuary were dominated by fibres (55.3 per cent, 76.6 per cent and 72.9 per cent, respectively), followed by fragments, films and other plastics. The prominent ubiquity of fibres in all three matrices suggests a variety of sources of MPs, most likely including domestic sewage, effluents from industries and laundry,” the study states.”Fragments were the second most abundant micro-debris in water (27 per cent) and biota (16.6 per cent). They mostly originate from the degradation/weathering of larger plastic pieces such as packaging materials, plastic bottles and other macro-plastic litter, which are often directly discarded into the estuarine environment,” the study adds.The research also found transparent spherical beads in the waters of the river along with sediments containing polypropylene, polyamide, polyacrylamide polymers.”These could originate from personal care products, textiles and wastewater treatment plants. Notably, no such beads were found in the shellfish and finfish samples,” it says.AdvertisementThe most commonly found MPs were plastics which were black in colour (43.9 per cent), which the study claims “might have come into the environment due to abrasion of tyres on the road surfaces as regular wear and tear”.The study, according to the researchers, was carried out to understand the abundance of MPs in the estuarine environment and how the particles find their way into seafood “through which humans may also be exposed”.As per the research, an average Indian consumes 10 kg of seafood per annum.”The average number of MPs in shellfish found in the present study is 2.6 MPs/g. Accordingly, the estimated annual intake of MPs from shellfish alone per capita for Goa would be 8084.1 particles per year per person. Shellfish, therefore, poses a possible threat in terms of consumption, as it is a local delicacy and also consumed by the many tourists in the area,” the study says.One of the top tourist states in the country, Goa is well known for its beaches and nightlife, as well as the variety of seafood on offer in the state’s coastal restaurants.The research comes a month after the NIO, one of the top marine research institutes in the country, indicated the presence of microplastics in government tap water supplied in Goa following research conducted along with a Delhi-based environmental consultancy firm.Reacting to the study, the state government in a rebuttal had questioned the NIO on why the central government’s Council for Scientific and Industrial Research had not approached the state government for collaboration during the study.**

The above article has been published from a wire agency with minimal modifications to the headline and text.

Maine will make companies pay for recycling. Here’s how it works.

The law aims to take the cost burden of recycling away from taxpayers. One environmental advocate said the change could be “transformative.”Recycling, that feel-good moment when people put their paper and plastic in special bins, was a headache for municipal governments even in good times. And, only a small amount was actually getting recycled.Then, five years ago, China stopped buying most of America’s recycling, and dozens of cities across the United States suspended or weakened their recycling programs.Now, Maine has implemented a new law that could transform the way packaging is recycled by requiring manufacturers, rather than taxpayers, to cover the cost. Nearly a dozen states have been considering similar regulations and Oregon is about to sign its own version in coming weeks.Maine’s law “is transformative,” said Sarah Nichols, who leads the sustainability program at the Natural Resources Council of Maine. More fundamentally, “It’s going to be the difference between having a recycling program or not.”The recycling market is a commodities market and can be volatile. And, recycling has become extremely expensive for municipal governments. The idea behind the Maine and Oregon laws is that, with sufficient funding, more of what gets thrown away could be recycled instead of dumped in landfills or burned in incinerators. In other countries with such laws, that has proved to be the case.Essentially, these programs work by charging producers a fee based on a number of factors, including the tonnage of packaging they put on the market. Those fees are typically paid into a producer responsibility organization, a nonprofit group contracted and audited by the state. It reimburses municipal governments for their recycling operations with the fees collected from producers.Nearly all European Union member states, as well as Japan, South Korea and five Canadian provinces, have laws like these and they have seen their recycling rates soar and their collection programs remain resilient, even in the face of a collapse in the global recycling market caused in part by China’s decision in 2017 to stop importing other nations’ recyclables.Ireland’s recycling rate for plastics and paper products, for instance, rose from 19 percent in 2000 to 65 percent in 2017. Nearly every E.U. country with such programs has a recycling rate between 60 and 80 percent, according to an analysis by the Product Stewardship Institute. In 2018, the most recent year for which data is available, America’s recycling rate was 32 percent, a decline from a few years earlier.Nevertheless, laws like these have faced opposition from manufacturers, packaging-industry groups and retailers.In Maine, the packaging industry supported a competing bill that would have given producers more oversight of the program. It also would have exempted packaging for a range of pharmaceutical products and hazardous substances, including paint thinners, antifreeze and household cleaning products.One of the industry’s main objections to the bill that ultimately passed was that it gave the government too much authority and left the industry with not enough voice in the process. “No one knows packaging better than our members,” said Dan Felton, the executive director of the packaging industry group Ameripen, in a statement following the passage of the law. “Funds should be managed by industry.”Recycling is important for environmental reasons as well as in the fight against climate change. There are concerns that a growing market for plastics could drive demand for oil, contributing to the release of greenhouse gas emissions precisely at a time when the world needs to drastically cut emissions. By 2050, the plastics industry is expected to consume 20 percent of all the oil produced.The oil industry, concerned about declining demand as the world moves toward electric cars and away from fossil fuels, has pivoted toward making more plastic — spending more than $200 billion on chemical and plastic manufacturing plants in the United States. Vast amounts of plastic waste are exported to Africa and South Asia, where they often end up in dumps or in waterways and oceans. In the ocean, they can break down into microplastics that harm wildlife.China’s decision in 2017 precipitated a crisis in recycling. Without China as a market to import all that waste, recycling costs soared in the United States. Dozens of cities suspended their recycling programs or turned to landfilling and burning the recyclables they collected. In Oregon alone, 44 cities and 12 counties had to stop collecting certain plastics like polypropylene.Gov. Janet Mills of Maine, a Democrat, signed the new recycling policies into law this month.Robert F. Bukaty/Associated PressTo cope, state legislators and environmental protection agencies began looking for solutions. A number of them, including Maine and Oregon, settled on what is known as an extended producer responsibility program, or E.P.R., for packaging products.In Maine, packaging products covered by the law make up as much as 40 percent of the waste stream.In both states, one important benefit of the program is that it will make recycling more uniform statewide. Today, recycling is a patchwork, with variations between cities about what can be thrown in the recycling bin.These programs exist on a spectrum from producer-run and producer-controlled, to government-run. In Maine, the government is taking the lead, having the final say on how the program will be run, including setting the fees. In Oregon, the producer responsibility organization is expected to involve manufacturers to a larger degree, including them on an advisory council.In another key difference, Maine is also requiring producers to cover 100 percent of its municipalities’ recycling costs. Oregon, by contrast, will require producers to cover around 28 percent of the costs of recycling, with municipalities continuing to cover the rest.Built into both laws is an incentive for companies to reconsider the design and materials used in their packaging. A number of popular consumer products are hard to recycle, like disposable coffee cups — they’re made of a paper base, but with a plastic coating inside, and another plastic lid, as well as possibly a cardboard sleeve.Both Maine and Oregon are considering charging higher rates for packaging that is hard to recycle and therefore doesn’t have a recycling market or products that contain certain toxic chemicals, such as PFAS.For many companies, this might require a shift in mind-set.Scott Cassel, the founder of the Product Stewardship Institute and the former director of waste policy in Massachusetts, described the effect of one dairy company’s decision to change from a clear plastic milk bottle to an opaque white bottle. The opaque bottles were costlier to recycle, so the switch cost the government more money. “The choice of their container really matters,” Mr. Cassel said. “The producer of that product had their own reasons, but they didn’t consider the cost of the material to the recycling market.”Sorting plastics near Nairobi, Kenya. There is growing evidence that waste shipped to Africa and South Asia for recycling ends up in unregulated dumps or waterways.Baz Ratner/ReutersThirty-three states currently have extended producer responsibility laws on the books, but they are far more narrow. Typically they focus only on specific products, like used mattresses and tubs of paint.In those narrow applications, they have proven effective. Connecticut’s mattress, paint, electronic and thermostat E.P.R. programs have diverted more than 26 million pounds of waste since 2008, according to an analysis by the Product Stewardship Institute.A number of the packaging E.P.R. programs introduced in statehouses this year faced significant opposition from the packaging and retail industries, including the one in Maine. One of the industries’ main contentions was that the laws would lead to higher grocery prices for consumers. A study by the Oregon Department of Environmental Quality of Canadian E.P.R. programs found that consumer product prices had increased by only $0.0056 per item.Some major consumer-product companies have begun voicing support for policies like these. In 2016, Greenpeace obtained internal documents from Coca-Cola Europe, which depicted extended producer responsibility as a policy that the company was fighting. In a sign of change, this spring, more than 100 multinational companies, including Coca-Cola, Unilever, and Walmart, signed a pledge committing to support E.P.R. policies.Sustainability and Climate Change: Join the Discussion The New York TimesOur Netting Zero series of virtual events brings together New York Times journalists with opinion leaders and experts to understand the challenges posed by global warming and to take the lead for change. Sign up for upcoming events or watch earlier discussions.

We’re eating and drinking Great Lakes plastic. How alarmed should we be?

Editor’s note: This is the third entry in a series examining the causes, impacts and solutions to plastic pollution in the Great Lakes. Read the first and second stories here.Thirsty? Would you like a little plastic with your drinking water?That may sound ridiculous, but researchers say it has, unfortunately, become a serious problem that bears further study as evidence mounts that people are eating, drinking and inhaling microscopic pieces of plastic on a regular basis.In Michigan, water utility managers say microplastic contamination is matter of emerging concern, but the problem ranks lower on the priorities list because research into the overall ubiquity and health implications of such contamination is in its infancy.The story is similar for microplastics in food — particularly in fish harvested from the Great Lakes, which are, sadly, awash in plastic fragments. The smallest pieces are entering the base of the food web and showing up in fish guts. But how those tiny particles are affecting the health of animals and potentially the humans that eat them isn’t well understood.“We’re breathing this stuff in, too,” said Sherri Mason, sustainability coordinator at Penn State Behrend who studies microplastic in the Great Lakes.Ever since Mason began speaking in public about plastic pollution, the question of how the manmade material is affecting humans has been frequently asked.“That is always where it leads to,” Mason said. “It’s frustrating that we don’t have all the answers. But the data we have right now is not (encouraging).”When it comes to plastic in tap water, all eyes are on California as the most populous U.S. state develops regulatory guidelines for microplastics in drinking water. The state’s Water Resources Control Board is expected this year to issue a preliminary safety threshold for the microscopic particles, which are defined as three-dimensional in shape and less than five millimeters long.The effort is complicated by the lack of standardized test methods for microplastics in drinking water and a relative scarcity of research on their ubiquity and health impacts. But researchers say it’s an important precautionary step that’s probably overdue.“We now know that we live in a soup of plastic that is getting ever denser. And we don’t seem to be changing our ways. And the contaminants, they live longer than we do, meaning that the soup will get thicker,” Rolf Halden, director of the Biodesign Center for Environmental Health Engineering at Arizona State University, told the nonprofit news site CalMatters.“So, is it too early to do something? No, it is actually a bit late.”In the Great Lakes region, Mason co-led a 2018 study that found microplastic fibers in 159 samples of tap water from around the world, including 12 brands of beer brewed with Great Lakes source water and 12 commercial sea salt brands.Most of the plastics in the water samples were tiny fibers, which are suspected to have come from the air. That makes it a difficult problem for utilities to control.“As soon as your water comes into contact with air, that’s got microplastics in it,” Mason said. “I think utilities feel like there’s nothing they can do.”A Loyola University Chicago student exams micro plastic with a microscope at an environmental research lab at Loyola in Chicago, Ill. on Thursday, July 22, 2021. (Joel Bissell | MLive.com)Joel Bissell | MLive.comUtility managers discuss microplastics at conferences, but “I can’t say that utilities are particularly focused on it,” said Bonnifer Ballard, director of the Michigan Section of the American Water Works Association, a trade group that represents municipal water utilities. “It’s clearly getting through the system, but I don’t think its pervasive, so it doesn’t rise to the top in terms of concerns.”The longevity of plastic — which can last for hundreds of years, breaking down into smaller pieces as time goes by — is a major concern for Myron Erickson, public utilities director for the city of Wyoming, which draws its water from Lake Michigan.But Erickson is less concerned about people consuming microplastic through municipal water systems because conventional treatments that process surface water from lakes and rivers are meant to remove solid particles. Once the water percolates through a filter bed, Erickson said it doesn’t see the light of day again until it comes out someone’s tap.“It’s a closed, pressurized system by design. There really isn’t a way for it to become contaminated,” he said. “That’s not to say it’s impossible, but that’s not where I’m worried when I think microplastics. I’m worried about the oceans, the air we’re breathing and the fact that there isn’t ever going to be a Flint or a Belmont of microplastics to bring it to population’s attention. The Belmont and Flint of microplastic is Planet Earth.”But evidence suggests that some plastic is coming out of the tap. The 2018 study which found microplastic in tap water samples from around the globe included 33 samples from the United States with an overall average of more than nine plastic particles per sample. Researchers in the effort took precautions to avoid potential airborne fiber contamination.Tap water from Holland, Alpena, Chicago, Milwaukee, Duluth, Buffalo and Clayton, N.Y., all contained at least one microplastic fiber. Each of those utilities draws water from a Great Lakes intake. But beer brewed with that water contained more particles overall, leading study authors to conclude the results “indicate that any contamination within the beer is not just from the water used to brew the beer itself.”“That’s almost certainly coming from employees and humans making and handling and bottling the beer,” said Erickson. “Drinking water doesn’t really work that way.”Bottled water — typically packaged in single-use plastic bottles and generally subject to less regulatory oversight than public utilities — appears to contain more plastic on average than tap samples, according to another 2018 study led by Mason. Analysis of nearly all major bottled brands sourced from around the world found an average of 10 particles per liter. Water bottled in glass had lower particle counts and authors wrote that “data suggests the contamination is at least partially coming from the packaging and/or the bottling process itself.”When it comes to the Great Lakes, another major point of concern for human ingestion of plastic is through contaminated fish. Microplastic fibers are showing up in high quantities in fish guts, but the question researchers are still driving toward is whether those particles are being absorbed into fish tissue that people would consume.A dead cormorant, a type of diving bird, is bird is tangled up in plastic balloon ribbon at the Elberta, Mich. beach pier on Lake Michigan, Aug. 14, 2021. Balloon debris is among the 22 million pounds of plastic estimated to enter the Great Lakes each year. (Garret Ellison | MLive)Garret Ellison | MLiveWhat is abundantly clear is that rivers are bringing plastics from various sources to the Great Lakes and, along the way, fish in those rivers are eating them. In 2016 and 2017, Loyola University Chicago biologists sampled 74 fish from the Muskegon and St. Joseph rivers in Michigan and the Milwaukee River in Wisconsin. They found that 85 percent had microplastics in their digestive tract, with an average of 13 particles per fish.Canadian researchers published a study this year which found a record 915 particles in the digestive tract of a Lake Ontario brown bullhead. High particle counts were found in other fish, including white suckers from Humber Bay and Toronto Harbor, which had more than 500 particles apiece. A longnose sucker from Lake Superior’s Mountain Bay had 790 particles. In the Humber River, up to 68 particles were found in common shiner minnows.“Microplastic is interacting with aquatic wildlife,” said Rachel McNeish, a post doc researcher on the Loyola study. “Fish are consuming it — either actively eating it thinking its food, eating insects with microplastic in them or maybe just drinking water with microplastic. Or they may consume it through contact with sediment. In any case, microplastic is entering the food web.”Does that mean fish which ate plastic pose a health risk to humans?John Scott, a chemist at the Illinois Sustainability Technology Center (ISTC) who studies microplastics, said particles in the lakes are known to absorb and concentrate contaminants such as PCBs, PFAS, DDT, flame retardants and other toxic chemicals. When it comes to chemicals, the question is whether or not the plastics eaten by fish amplify biomagnification of contaminants up the food chain. In other words, are they making larger fish more unsafe to consume than they otherwise would be?In 2018, researchers suspended plastic nurdle pellets in Muskegon Lake for three months. After one month, they found pollutants like PFAS, PCBs and PAHs had concentrated in a biofilm that developed on the pellets at levels hundreds of times higher than background levels.“There is that potential for magnification,” said Alan Steinman, a Grand Valley State University researcher who led the study — which led to more questions. “If it’s taken up by an organism, we don’t know if it will be further biomagnified and have a negative impact.”Scott, who was co-author on the Muskegon Lake study, said chemical additives in plastic — which is primarily made using fossil fuels — are also a concern. “There’s thousands of these additives in plastic and not at trivial levels,” he said.To cross biological membranes and not be simply expelled by the body as waste, plastic particles would have to break down to nanoplastic levels. Research on the toxic effects of plastic on humans micro and nano levels is still in its infancy, but some studies have indicate the potential for serious problems. A 2021 scientific review in the journal Nanomaterials noted that researchers have already been able to demonstrate the microscopic particles are “able to cause serious impacts on the human body, including physical stress and damage, apoptosis, necrosis, inflammation, oxidative stress and immune responses.”“Everyone is talking about microplastic, but down the road, I think that might shift to nano or even pico plastics,” Scott said. “Those things are more liable to get into the body and stay there.”Related stories:Great Lakes plastic pollution is only getting worseIndustrial plastic pellets litter Great Lakes beachesZeeland plastic powder spill sparks evacuationsMicroplastic fibers prevalent in Great Lakes tributariesAnn Arbor eyes ban on single-use plasticsLawmakers want to ban the ban on plastic bag banningMichigan PFAS site list surges past 100 amid new standards

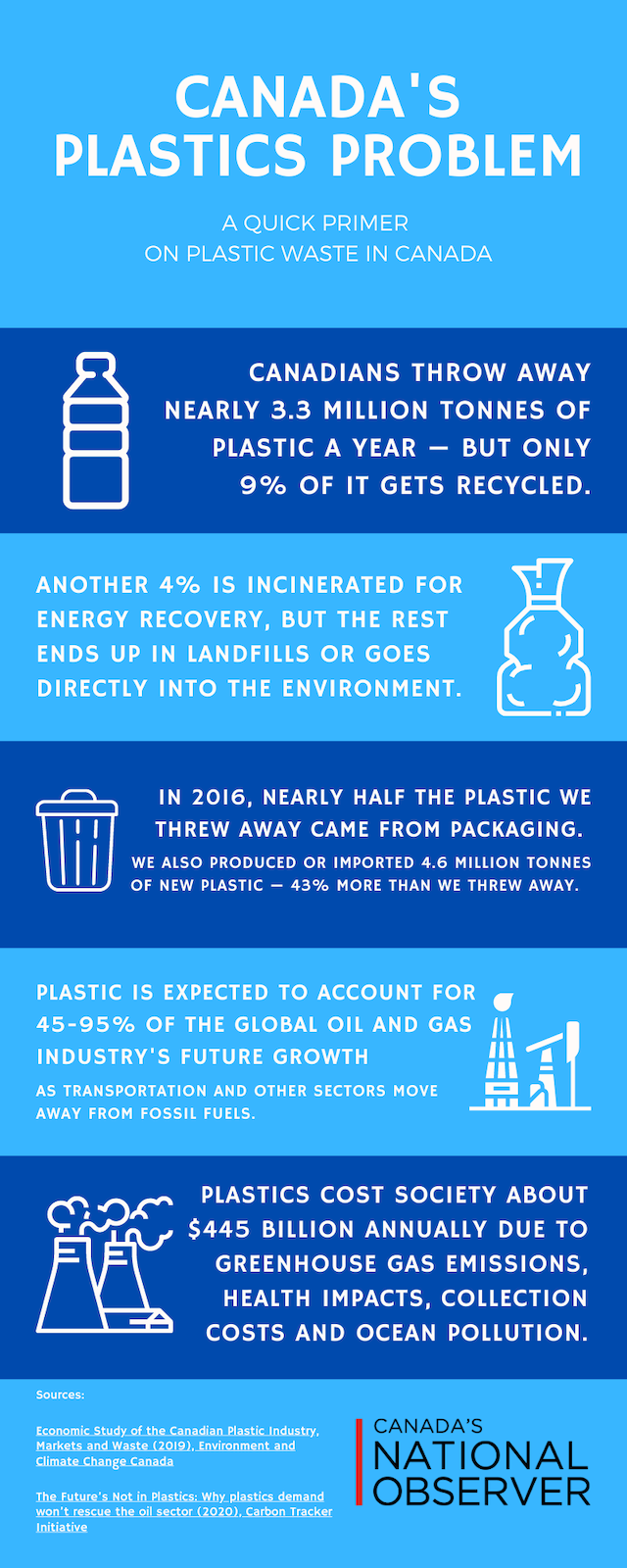

This election could decide how Canada fights plastic pollution. Here's where the parties stand

Climate change and COVID-19 aren’t the only issues on the ballot for Canadians when they head to the polls in a few weeks. Plastic is driving a global pollution problem that is choking our environment and potentially harming human health, and Canada’s future efforts to end it are on the line. Each year, Canadians produce millions of tonnes of plastic waste. Over 90 per cent ends up in landfills or the environment. The remainder is recycled, according to a 2019 report commissioned by Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC), but observers warn some waste destined for recycling likely ends up in incinerators and cement kilns, or is shipped overseas illegally. Plastic also plays a role in deciding the future of the oil and gas industry. As the world shifts to renewable energy sources, fossil fuel companies are banking on plastic production to fuel their growth — a move that could drive greenhouse gas emissions. Get top stories in your inbox.Our award-winning journalists bring you the news that impacts you, Canada, and the world. Don’t miss out.The previous Liberal government in May listed plastic as toxic under Canada’s main environmental law. The decision was the first in a suite of planned regulations — including a ban on six single-use items, like plastic straws and six-pack rings — aimed at reducing Canada’s plastic waste and pollution. While environmental advocates largely applauded the move, many warn Canada’s next government will need to implement stronger regulations to tackle the plastic problem. “For so long, governments have tried to tackle plastic pollution from the waste end through trying to improve… the fiction of recycling plastic,” explained Elaine Macdonald, director of Healthy Communities for Ecojustice, an organization advocating for better environmental laws. “The only solutions that are really going to make a dent now are going to be the ones that are targeting non-essential plastic production.”Canada’s National Observer scoured the four main federal parties’ platforms for their positions on key issues in the plastic debate, from recycling to regulations, to see what the future could hold for plastic in Canada. (The Bloc Québécois doesn’t mention plastic in its 2021 platform.) What people are reading Will Canada ban single-use plastic?In 2019, the former Liberal government announced plans to ban six harmful single-use plastic items: plastic checkout bags, straws, six-pack rings, stir sticks, plastic cutlery and food containers made from hard-to-recycle plastics. Many of these items are ubiquitous; for instance, Canadians use up to 15 billion plastic bags each year, according to ECCC. While environmental advocates welcomed the move, many pointed out the banned items only represent a small portion of the single-use plastic Canadians use. Ending plastic pollution will require wider bans to force companies to develop better reusable materials on top of regulations curbing new plastic production, they said. Here’s where the parties sit on the issue: The Liberals have pledged to pursue their planned plastic regulations, including a ban on the six single-use plastic items. Their platform also promises tweaks to federal procurement policies to “prioritize” reusable and recyclable materials. The Conservatives have said they will not pursue the regulations on plastic proposed by the previous government, including “showy” bans, according to their platform. However, environmental groups have noted that while bans can’t solve the problem entirely, they can go a long way to reducing plastic — an essential step to ending plastic pollution. Single-use plastics would be immediately banned under an NDP government, the party has promised. It is also the only party to pledge support for workers in Canada’s $28-billion plastics industry to transition to new, more sustainable industries. The Greens would maintain the previous government’s planned regulations on plastic waste but expand the list of banned single-use items. Similar to the Liberals, the party has pledged to support “green procurement” policies that would see governments and businesses purchasing more sustainable plastic products.Is plastic a toxic substance? Earlier this spring, the federal government designated plastic as “toxic” under the Canadian Environmental Protection Act (CEPA), Canada’s primary environmental law. A material can be considered legally “toxic” if it harms human health, the environment or biodiversity. Plastic pollution, which harms marine animals and birds, meets those criteria, according to an ECCC study.The designation opens the door to future regulations on plastic, such as bans on some items, rules requiring plastic sold in Canada to contain a certain amount of recycled materials and potential curbs on plastic production. The decision was opposed by Canada’s plastics industry, and several major plastic producers have since launched legal action against the federal government’s decision. Here’s where the parties sit on the issue: In October 2020, the former Liberal government announced a wide-ranging plan to curb plastic pollution, including designating plastic as toxic. If re-elected, the party has committed to pushing this plan forward. While the Conservative platform decries the Trudeau government’s decision to list plastic as toxic, it does not specify whether the party will try to take the material off the toxic list. The NDP has committed to banning single-use plastics, a move easily done now that plastics are considered toxic under CEPA. The party also supported the Liberals’ decision to list the material as toxic. The Green Party has pledged to maintain the Liberal government’s planned regulations for plastics, including the toxic designation. Can recycling solve the problem — and who pays for it?Plastic recycling didn’t exist until the 1970s, when it was “formalized and launched” by the Container Corporation of America in response to growing concern over the material’s environmental impact. Recycling promised to transform used plastic into new products — if people and governments took on the responsibility for sorting and collecting millions of tonnes of used material each year, explains Max Liboiron, a plastic expert and professor at Memorial University. Decades later, recycling has mostly failed. Only about 305,000 of the millions of tonnes of plastic waste generated in Canada is recycled, according to a 2019 ECCC report. Despite these dismal numbers, all the parties have promised to improve Canada’s plastic recycling: The Liberals have pledged to continue supporting provincial and territorial efforts to make plastic producers pay for recycling and waste disposal, and have said they will create a federal registry of plastic producers. The party has also promised $100 million to support “technologies and solutions” for the reuse of plastics. The Conservatives promise to ensure plastic waste is “responsibly” recycled but make no mention of implementing rules that would force plastic producers to cover the costs of recycling their products. However, the party has promised to invest heavily in technologies that transform plastic waste into fuel — an approach critics say will do more environmental harm than good. The NDP has pledged to boost requirements forcing plastic producers to cover the cost of recycling their products. However, unlike the Liberals, their platform suggests these would be national standards, not left to the provinces and territories. The party has also pledged to help municipalities develop better waste management systems. The Greens make no mention of requirements to make plastic producers pay the recycling costs of their products. However, the party has promised to implement tax rebates or waivers on recycling initiatives, and says in the party platform it will promote “sustainable waste management.” Plastic pollution is a global problem. Will Canada help solve it? Every day, Canadian companies send about 80 truckloads of plastic waste into the U.S. The shipments are a key part of a plastic trade between the two countries worth $18.8 million, but it’s unclear whether they are recycled, stuffed in an American landfill or shipped overseas in contravention of Canada’s international commitments.Canada (and most countries except the U.S.) has signed the Basel Convention, an international agreement that bans countries from exporting hazardous waste, including plastic, minus a few exceptions. However, advocates worry Canadian waste is passing through the U.S. — an exemption lets Canada trade its trash with our southern neighbour — for disposal or recycling in lower-income countries, where it can more easily threaten the environment and local food security. Unlike other global environmental issues like the climate crisis and persistent toxic pollutants, there are no international treaties on plastic pollution that tackle everything from production to disposal, making a co-ordinated solution to the problem nearly impossible. Still, observers say efforts by several countries to create a legally binding global plastic treaty could be minted within a few years — but Canada’s support for the effort remains unclear.Here’s where the parties sit on the issue: In 2018, the former Liberal government and five other countries, including the European Union, launched the Oceans Plastic Charter, a voluntary pledge by countries and businesses to help reduce ocean plastic pollution. The party has promised to continue working on this effort in addition to supporting the development of a global agreement on plastic. However, the party is unclear about its support for a legally binding treaty, which experts say is essential to end the crisis. The Conservatives have pledged to ban the export of plastic waste, except waste destined for recycling, a promise that echoes a private member’s bill put forward last year by Conservative MP Scott Davidson. The bill has been criticized by environmental groups for allowing plastic waste to be exported for recycling in countries without adequate recycling infrastructure or strong environmental laws and monitoring. The party makes no mention of supporting a legally binding plastics treaty — an essential tool, experts say, to ending plastic pollution worldwide. All plastic waste exports would be banned under an NDP government. The party’s platform doesn’t mention its position on international efforts to end plastic pollution. If elected, the Greens would push for a legally binding global plastics treaty — a position no other party has yet made. They have also pledged to tighten Canada’s plastic waste export laws.

The big problem with plastic

Legislative changes and consumer pressure could certainly create more of a market for at least some of the plastic that is now going straight into incinerators and landfills, says Wright, of the National Waste & Recycling Association. A legal requirement or company commitment to use more recycled material in plastic products, including those made of less frequently recycled plastics, could create incentives for manufacturers to make more recyclable products and for recycling facilities to do a better job sorting, processing, and actually recycling that material.For example, the high demand for the type 1 plastic used in PET beverage bottles is largely due to consumers pressuring beverage companies to improve recycling processes and lawmakers requiring them to use a certain percentage of recycled plastic in their products. A California law passed last year, for instance, requires beverage bottles to be made of 15 percent recycled plastic. That will increase to 25 percent by 2025 and 50 percent by 2030. Requirements like these “force manufacturers to change the makeup of their products, to use more recyclable plastic or more environmentally friendly materials,” says Shanika Whitehurst, associate director of product sustainability, research, and testing at CR.

“Consumers really can change and push a market,” says Shelie Miller, PhD, a professor at the University of Michigan School for Environment and Sustainability. “Plastic companies are actively looking into better recycling methods and how to design plastics to be more easily recyclable because they know this is such an important consumer issue.” The American Chemistry Council recently said it supports a national standard that would require all plastic packaging to contain at least 30 percent recyclable material by 2030.

Another part of the solution, according to Enck, Lifset, and others, is extended producer responsibility (EPR), which would require plastic makers and sellers to be responsible in some way for the life cycle of their products, including cleanup after they are sold. EPR usually involves producers either implementing collection programs themselves or funding local collection programs to ensure more products are recycled. An EPR system in British Columbia, for example, increased the share of plastic waste collected for recycling from 42 percent in 2018 to 52 percent in 2020.

In 2021, Maine became the first state in the U.S. to pass EPR legislation addressing packaging waste. The law will levy fees on companies that create or use packaging; fees will be lower for practices with less environmental impact, like using more recyclable materials. The fees will be used to fund local recycling efforts. Oregon passed an EPR law soon after Maine, and six other states have EPR bills in the works.

Enck says another worthy goal is eliminating single-use plastics, like plastic bags and polystyrene foam. But for such a change to have a positive impact, the items that replace them have to actually be reused—and often, says the University of Michigan’s Miller. “Someone who goes to the grocery store and forgets to bring reusable bags and every time buys a new reusable bag is creating a more [harmful] single-use item,” she says.

That suggests the real shift consumers need to make: More than just avoiding plastic, we need to evaluate our behavior and move away from unnecessary consumption and living a throwaway lifestyle. “If we’re really honest, any solution will require us to analyze our own consumption to try to understand what we’re consuming and why, and whether there are ways to reduce our individual consumption,” Miller says. She acknowledges that’s a tall order for a lot of people. It’s much easier to say “I can consume anything I want. I’ll just recycle it.”

Plastic pollution: Could recycling PPE reduce the problem?

Discarded face masks could be melted down and recycled to help tackle plastic pollution.It is estimated 129 billion single-use face masks are used monthly around the world, with 55 million a day in the UK.The Welsh government has set a target on creating no waste in Wales by 2050 and a recycling expert wants the NHS to set an example by recycling PPE.One Welsh firm is now working to turn hospital waste into new masks with 65% recycled materials.Old PPE like face masks, which people in the UK go through about 19 billion every year, is currently incinerated – producing climate-warming carbon emissions – or sent to landfills.Step-by-step guide to making your own face maskSmall changes you can make for a greener lifeHermit crabs mistake plastic pollution for foodMat Rapson, managing director of Cardiff-based Thermal Compaction Group – or TCG, said was a “huge problem”.”We use 55 million masks a day in the UK and globally the figure is 129 billion masks, a lot of which is being discarded into landfills,” he said.How does it work?TCG is already working with seven hospital trusts across the UK, which are using thermal heating devices to melt down PPE.The firm heats single-use masks, gowns and curtains to 300C, sterilising all pathogens, and is recycling 300,000 defective masks each month, which would have otherwise been incinerated or sent to landfill.It turns them into 1m-long blocks that are 99.6% polypropylene – made up of about 10,000 masks – which can be used to make products such as plastic chairs, buckets and toolboxes. “If a mask goes into landfill, or worse beaches or rivers, it takes 450 years to decompose,” Mr Rapson said.”It’s ridiculous. We’re just discarding these single-use disposable items, but they’re not single-use, they can be recovered and remade multiple times.”The ideal is that all hospital PPE waste gets recovered and made back into masks for hospitals.”Linda Ball, chief executive of Upcycled Plastics, said the firm was making masks using plastic waste recovered from the sea.She said the manufacturing process resulted in a 36% reduction in carbon emissions, and she believed the NHS, the UK’s largest user of disposable PPE, could cut its impact significantly by switching to recycled PPE.She said: “The biggest problem that we have in the medical industry is single-use plastic.”If we keep buying stuff from China and bringing it over here, the amount of carbon usage is insane.”She said recycling masks, however, was a challenge as the ear hoops, the filter and the nose piece are often made from different types of plastic.Rob EliasDr Rob Elias, director of the Biocomposites Centre at Bangor University, said all PPE should be made in a way that it can be easily recycled, with one type of material making it “a heck of a lot easier to recycle in the future.”He said polypropylene in a mask can be recycled “five to six times” before it breaks down, but the challenge is “these recycling processes tend to be quite small at the moment, so they lack the scale”.”When you scale up the production process, you get massive energy savings.”But Dr Elias said it was a “great example” of the circular economy, where single-use products like disposable masks are put back into the economy for reuse instead of being thrown away. That is one of the key goals of the Welsh government’s Beyond Recycling strategy, which aims to have no waste produced in Wales by 2050.What is the solution to plastic pollution from PPE?Prof Gary Walpole, director of the Circular Economy Innovation Community Project at Swansea University, said recycling was something we should be doing an “awful lot more of” and public sector bodies such as the NHS could set an example by recycling PPE.”The basic premise of circular economy is to keep all products within the circular loop as long as possible,” he said.”There’s a lot of energy that goes into creating products like plastic, so the longer you can keep that plastic in use, by reusing it, the less energy use, the less raw material use, and therefore the less carbon you emit.”But Prof Walpole said getting the private sector to adopt this approach on a wider scale was difficult. He said one possible way forward would be to have the Welsh government mandate large organisations, such as the NHS and local authorities, into making the change.”The public services buy a lot of goods and services, so it’s a good place to start a different way of thinking,” he said. “This particular company is taking plastic products from the NHS where there are high volumes so they are able to leverage economies of scale, prove the concept, and then offer it out into the private sector.”It was also one solution to an increase in litter during the pandemic, including face masks and disposable gloves, according to Keep Wales Tidy.The campaign group said there has been a “significant and widespread increase in personal protective equipment being littered all over the country”, posing a danger to wildlife and public health. Mr Rapson said: “Plastic’s not the problem, it’s the infrastructure and we have one of the solutions here in Wales.”Plastic is not disposable, it’s not single use, we can actually embrace plastic and use it multiple times.”The Welsh government said: “We are aware of the TCG Sterimelt proposals and welcome innovation from industry to tackle the challenges of single-use plastics in healthcare settings as we move towards a circular economy by 2050.”IF YOU GO DOWN TO THE WOODS TODAY: Five friends bound together by a brutally fragile pact of silence…FIERCE AND FABULOUS: Hayley Goes… exploring the issues of her generation in a brand new series

Packaging generates a lot of waste – now Maine and Oregon want manufacturers to foot the bill for getting rid of it

Most consumers don’t pay much attention to the packaging that their purchases come in, unless it’s hard to open or the item is really over-wrapped. But packaging accounts for about 28% of U.S. municipal solid waste. Only some 53% of it ends up in recycling bins, and even less is actually recycled: According to trade associations, at least 25% of materials collected for recycling in the U.S. are rejected and incinerated or sent to landfills instead.

Local governments across the U.S. handle waste management, funding it through taxes and user fees. Until 2018 the U.S. exported huge quantities of recyclable materials, primarily to China. Then China banned most foreign scrap imports. Other recipient countries like Vietnam followed suit, triggering waste disposal crises in wealthy nations.

Some U.S. states have laws that make manufacturers responsible for particularly hard-to-manage products, such as electronic waste, car batteries, mattresses and tires, when those goods reach the end of their useful lives.

Now, Maine and Oregon have enacted the first state laws making companies that create consumer packaging, such as cardboard cartons, plastic wrap and food containers, responsible for the recycling and disposal of those products, too. Maine’s law takes effect in mid-2024, and Oregon’s follows in mid-2025.

These measures shift waste management costs from customers and local municipalities to producers. As researchers who study waste and ways to reduce it, we are excited to see states moving to engage stakeholders, shift responsibility, spur innovation and challenge existing extractive practices.

Holding producers accountable

The Maine and Oregon laws are the latest applications of a concept called extended producer responsibility, or EPR. Swedish academic Thomas Lindhqvist framed this idea in 1990 as a strategy to decrease products’ environmental impacts by making manufacturers responsible for the goods’ entire life cycles – especially for takeback, recycling and final disposal.

Producers don’t always literally take back their goods under EPR schemes. Instead, they often make payments to an intermediary organization or agency, which uses the money to help cover the products’ recycling and disposal costs. Making producers cover these costs is intended to give them an incentive to redesign their products to be less wasteful.

The idea of extended producer responsibility has driven regulations governing management of electronic waste, such as old computers, televisions and cellphones, in the European Union, China and 25 U.S. states. Similar measures have been adopted or proposed in nations including Kenya, Nigeria, Chile, Argentina and South Africa.

Scrap export bans in China and other countries have given new energy to EPR campaigns. Activist organizations and even some corporations are now calling for producers to become accountable for more types of waste, including consumer packaging.

Packaging helps sell consumer products, and consumers are starting to demand more sustainable containers.

What the state laws require

The Maine and Oregon laws define consumer packaging as material likely found in the average resident’s waste bin, such as containers for food and home or personal care products. They exclude packaging intended for long-term storage (over five years), beverage containers, paint cans and packaging for drugs and medical devices.

Maine’s law incorporates some core EPR principles, such as setting a target recycling goal and giving producers an incentive to use more sustainable packaging. Oregon’s law includes more groundbreaking components. It promotes the idea of a right to repair, which gives consumers access to information that they need to fix products they purchase. And it creates a “Truth in Labeling” task force to assess whether producers are making misleading claims about how recyclable their products are.

The Oregon law also requires a study to assess how bio-based plastics can affect compost waste streams, and it establishes a statewide collection list to harmonize what types of materials can be recycled across the state. Studies show that contamination from poor sorting is one of the main reasons why recyclables often are rejected.

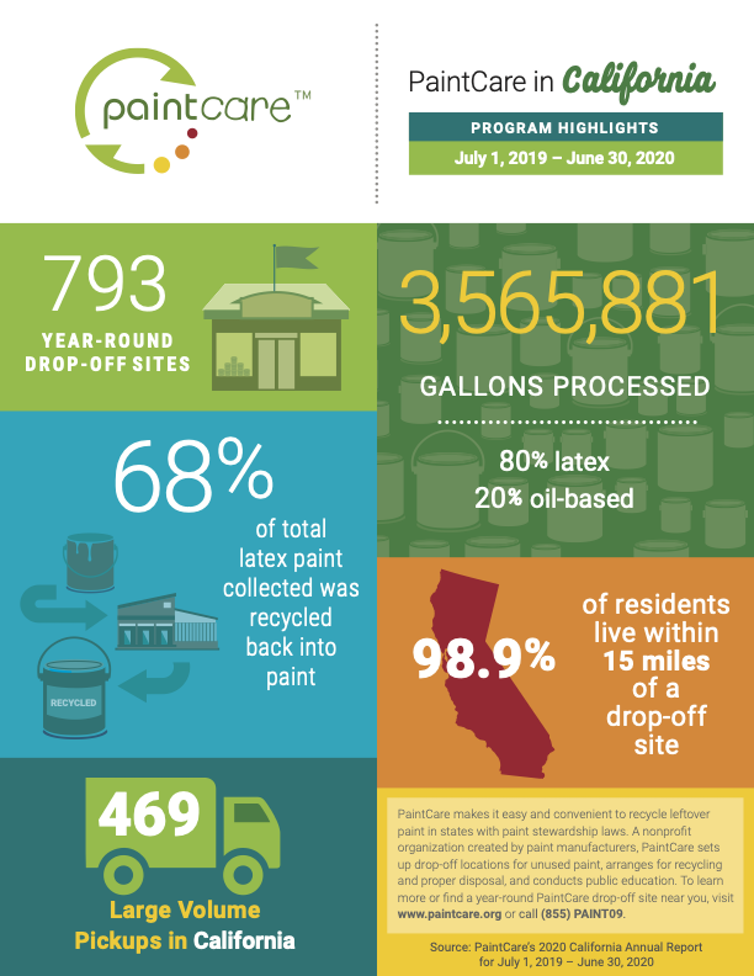

California paint recycling data from PaintCare, a nonprofit stewardship organization that runs paint recycling programs across the U.S.

PaintCare

Some extended producer responsibility systems, such as those for paint and mattresses, are funded by consumers, who pay an added fee at the point of sale that is itemized on their receipt. The fee supports the products’ eventual recycling or disposal.

In contrast, the Maine and Oregon laws require producers to pay fees to the states, based on how much packaging material they sell in those states. Both laws also include rules designed to limit producers’ influence over how the states use these funds.

Will these laws reduce waste?

There’s no clear consensus yet on the effectiveness of EPR. In some cases it has produced results: For instance, Connecticut’s mattress recycling rate rose from 8.7% to 63.5% after the state instituted a takeback law funded by fees paid at the point of sale. On a national scale, the Product Stewardship Institute estimates that since 2007 U.S. paint EPR programs have reused and recycled almost 24 million gallons of paint, created 200 jobs and saved governments and taxpayers over $240 million.

Critics argue that these programs need strong regulation and monitoring to ensure that corporations take their responsibilities seriously – and especially to prevent them from passing costs on to consumers, which requires enforceable accountability measures. Observers also argue that producers can have too much influence within stewardship organizations, which they warn may undermine enforcement or the credibility of the law.

Few studies have been done so far to assess the long-term effects of extended producer responsibility programs, and those that exist do not show conclusively whether these initiatives actually lead to more sustainable products. Maine and Oregon are small progressive states and are not major centers for the packaging industry, so the impact of their new laws remains to be seen.

However, these measures are promising models. As Martin Bourque, executive director of Berkeley’s Ecology Center and an internationally known expert on plastics and recycling, told us, “Maine’s approach of charging brands and manufacturers to pay cities for recycling services is an improvement over programs that give all of the operational and material control to producers, where the fox is directly in charge of the hen house.”

We believe the Maine and Oregon laws could inspire jurisdictions like California that are considering similar measures or drowning under waste plastic to adopt EPR themselves. Waste reduction efforts across the U.S. took hits from foreign scrap bans and then from the COVID-19 pandemic, which spurred greater use of disposable products and packaging. We see producer-pay schemes like the Maine and Oregon laws as a promising response that could help catalyze broader progress toward a less wasteful economy.

[Understand new developments in science, health and technology, each week. Subscribe to The Conversation’s science newsletter.]