This guide was developed to help provide an overview of chemicals and toxins used in food containers, as well as the related negative health impacts. We provide context and background information to help you understand which chemicals are used, why they are of concern, and how regulations aim to reduce the toxicity of food containers.

See the table of contents below for quick navigation.

Summary of Key Takeaways

- Food containers include anything that comes into contact with food, such as containers, packaging, and dishes.

- Food containers are often made of plastic, which is produced using thousands of chemicals.

- Chemicals used in food containers can “migrate” from the plastic into the food.

- Chemicals used in food containers such as BPA, phthalates and PFAS can cause negative health impacts. More research is needed to study the toxicity of these chemicals and the thousands of other chemicals used in food containers.

- Some countries and states have implemented regulations to try and combat the use of unsafe chemicals in materials that touch food.

Table of Contents

What are Food Containers?

The definition of food containers is quite broad, and includes anything that comes into contact with food, including containers, packaging, utensils, kitchen equipment and dishes. These materials are known to regulators as food contact materials (FCMs) or food contact substances (FCSs). Food containers may be made of a variety of materials including plastics, rubber, paper and metal.

The majority of food containers use plastics, as they are resistant to water and grease. Plastic is a popular choice for food storage or transport as plastic containers are hygienic, easy to clean (and keep sterile), convenient, and help maintain a food’s shelf life.

Despite the material’s popularity, there is little information on the long-term effects of plastics, plastic coatings, and plasticizers when it comes to our health. Food contact materials, including plastic ones, are made up of thousands of chemicals, although not all of these are toxic. However, greater than 60 percent of the chemicals used in food containers have an unknown toxicity.

Which Chemicals Are Used in Food Containers?

There are thousands of chemicals used in food containers, but there is little information on each substance. Health experts have identified three substances of high concern: bisphenol A (BPA), phthalates, and per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS).

Visit this database for a more complete list of Food Contact Chemicals (Groh et al. 2020). The database now includes ~12,000 distinct chemicals used in the manufacture of food contact materials and articles worldwide.

Bisphenol A (BPA) – Bisphenol is a chemical substance that is industrially produced. In fact, BPA is one of the most highly produced chemicals in the world, with over 2 million tonnes being produced worldwide per year.

BPA substance is colorless, and is used primarily to harden plastics. A derivative of BPA is used in epoxy resins. BPA is used in food storage containers such as the inner coatings of food cans, baby bottles, pitchers, tableware, and water bottles. These hard plastics may be identified by the recycling number 7 on the bottom of the product.

Despite BPA’s usefulness, many manufacturers are phasing it out due to health concerns. Most baby bottles made in the United States have not used BPA since 2009.

Phthalates – Phthalates are a class of chemicals known as plasticizers. Phthalates are most commonly added to PVC (polyvinyl chloride) to soften the plastic and increase its flexibility and durability. PVC is the third-most widely produced plastic polymer, with about 40 million tonnes produced per year.

Phthalates are used as plasticizers in PVC food packaging such as clear vinyl packaging or shrink wrap. PVC may also be used to create “blister packaging,” individual plastic pockets, for gum. The use of phthalates is decreasing in food packaging due to health concerns and safety regulations.

Plastics that may contain phthalates may be identified by the recycling number 3 on the bottom of the product.

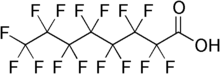

Per/Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) – Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, also known as PFAS or “forever chemicals”, are a manmade class of chemicals widely used in a number of applications. After their invention in the 1930s, PFAS became extremely popular due to their ability to repel oil, water, and grease.

PFAS contain bonds between carbon and fluorine atoms, which is an extremely strong chemical bond that is difficult to break down. Thus, PFAS are often referred to as “forever chemicals” due to their extreme environmental persistence.

PFAS are often used as a treatment to make food containers resistant to grease or water. This includes fiber-based packaging, such as pizza boxes or fast-food containers, as well as nonstick cookware.

The most common PFAS chemicals are perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS), which are no longer produced in the U.S. Many manufacturers have replaced these chemicals with other PFAS or other chemicals.

Exposure to Chemicals in Food Containers

The main method by which humans are exposed to chemicals in food containers is through migration of the chemicals into food. Laboratory and real-world studies show that chemicals in packaging materials almost always leach into food, even if it is only small quantities.

A 2020 meta analysis notes that around 1200 peer-reviewed studies demonstrate migration of chemicals from food contact materials into food (Muncke et al., 2020). Thus, food contact materials are a clear pathway for human exposure to chemicals.

The extent of how much migration occurs depends on various factors, including:

- Characteristics of the packaging (such as thickness and chemistry)

- Food temperature

- Storage time

- Size of the packaging surface in contact with food

Studies do not exist for many of the thousands of chemicals used in food contact materials. Not only is it difficult to obtain information about chemicals used in food contact materials, including the amounts used, but there is also very little information about these chemicals’ ability to migrate into food and expose humans. This lack of information extends to the impacts on human health, as many of these chemicals also have little to no hazard testing performed.

BPA, Phthalates, and PFAS Leaching

BPA, Phthalates and PFAS are among the most researched food contact chemicals as they are both widely used and they are of health concern.

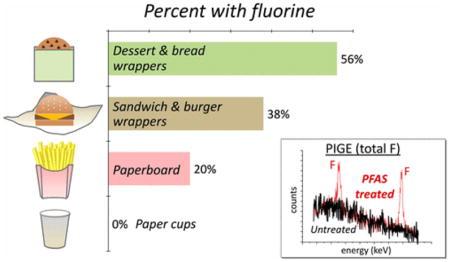

A 2017 study showed that PFAS in grease-resistant food packaging can leach into food and increase dietary exposure. This conclusion was reached after studying around 400 samples of food contact papers, cardboard containers, and beverage containers from fast-food restaurants (Schaider et al., 2017).

Source: Schaider et al. 2017

Multiple studies show the presence of BPA, phthalates or PFAS chemicals in the human body as a result of exposure through food contact materials. A 2011 study from the Silent Spring Institute showed that BPA and bis(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (also known as DEHP) can be detected in people, but that the levels of these chemicals in the human body are significantly reduced when diets are restricted to limited packaging (i.e. when exposure to food contact materials is decreased) (Rudel et al., 2011). Exposure to BPA is heightened when packaging containing BPA is heated.

It has also been shown that PFAS levels are higher in people who have recently eaten food from a fast food, pizza or other restaurant, or who have eaten popcorn from microwaveable bags (Susmann et al., 2019).

Exposure to these chemicals is widespread; a 2003-2004 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey conducted by the CDC found detectable levels of BPA in 93% of over 2500 urine samples from people ages six and up. The same study found that measurable levels of phthalate metabolites are common in the general U.S. population.

Health Impacts of Chemicals in Food Containers

Chemicals from food containers can have serious impacts on human health. In addition to being known hormone disruptors, BPA, phthalates, and PFAS may cause disease and other health issues.

Source: NIEHS

BPA – The toxicity of BPA remains controversial, as some studies show negative health impacts while others do not. To date, the US FDA considers bisphenol A (BPA) to be safe as a food contact material.

However, some research shows that BPA is an endocrine-disrupting chemical (EDC), and toxic for reproduction. It causes developmental effects in laboratory animals. Some human studies indicate BPA exposure is related to health effects like diabetes or heart disease.

Phthalates – The human health effects of phthalates are also subject to some debate. Some studies show that phthalates act as endocrine disruptors and affect reproduction. However, more research is needed on the effects of phthalates on humans.

One study estimated phthalate exposures are associated with around 100,000 American deaths per year, but a direct causal link is not yet proven (Trasande et al., 2021).

PFAS – PFAS are particularly dangerous because they are very slow to break down and can bioaccumulate in the environment or the human body over time. Peer-reviewed studies have shown that exposure to PFAS (particularly at high levels) can cause serious health effects.

PFOA and PFOS in particular are known to cause reproductive and developmental, liver and kidney, and immunological effects in lab animals, as well as tumors. In humans, they cause increased cholesterol levels, low infant birth weights, effects on the immune system, cancer (PFOA), and thyroid hormone disruption (PFOS).

Part of the difficulty of determining the health impacts of PFAS is that there are thousands of different PFAS chemicals that may have varying uses, exposure pathways, and toxicities. Additionally, people may be affected by PFAS differently at different times in their lives.

Learn more about ongoing PFAS research and get other government resources from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency website.

Toxicity of Food Contact Chemicals: An Ongoing Question

The true extent of health impacts caused by food contact materials are still unknown. While many nations regulate food contact materials because the risk of migration of chemicals into food is recognized, the vast majority of approved food contact materials have been inadequately studied or have unknown toxicities.

Additionally, many studies showing negative impacts of food contact chemicals have been performed only on laboratory animals, and must be confirmed in humans.

Environmental Impacts of Chemicals in Food Containers

While chemical leaching through food containers is one of the most direct exposure routes for humans, BPA, phthalates, PFAS and other chemicals typically used in food containers are found in the environment as well.

Chemicals in containers can enter the environment:

- Directly through manufacturing of plastics

- Indirectly through disposal of chemical-containing materials

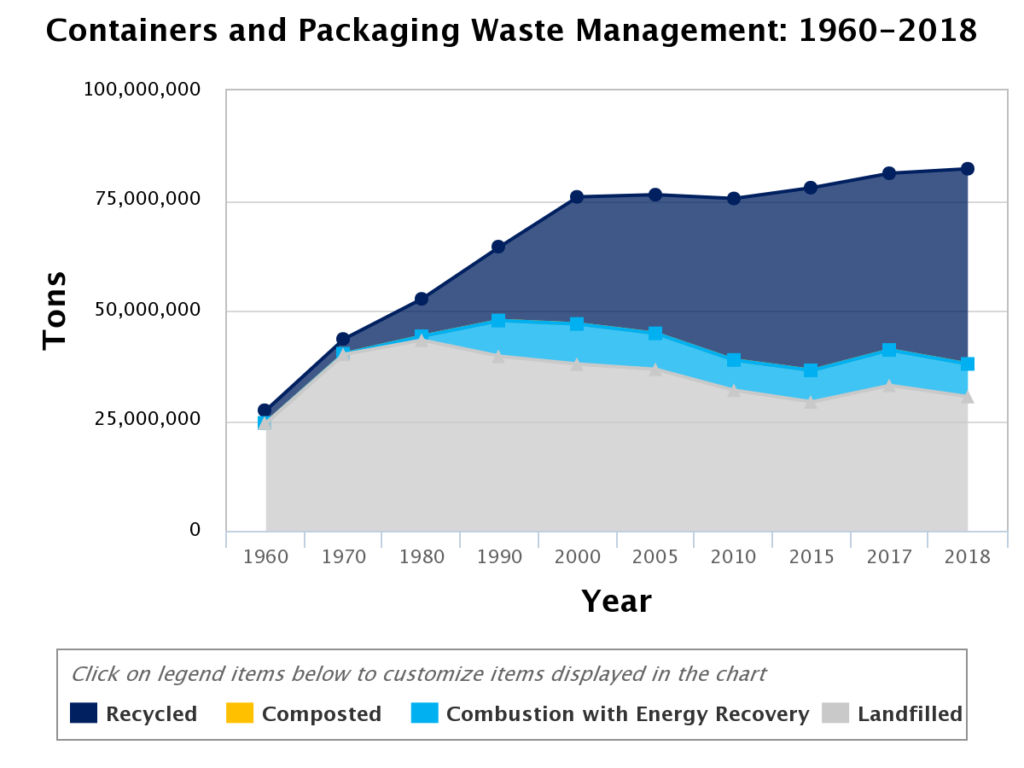

While containers and packaging make up a large percentage of waste produced in the U.S., very little is recycled (EPA Report about Materials, Waste, and Recycling). For example, in 2018, over 14,000 tons of plastic packaging were produced, and 10,090 of those tons went to landfill. Less than ⅓ was recycled.

When plastics are put into landfill rather than properly recycled, BPA and other chemicals can leach out into the environment over time. Chemical leaching into water or soil can have severe impacts on the environment as well as on humans. Drinking chemical-contaminated water can introduce chemicals into the human body, as can eating food grown in contaminated soil. Industrial chemicals in water also impact wildlife, causing developmental and reproductive problems.

Food Contact Materials Regulations

In the U.S., chemicals must prove toxicity above certain thresholds to be disapproved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Most PFAS, BPA, and phthalates remain legally approved for use in food contact materials, as the FDA does not have sufficient evidence of their toxicity.

The FDA’s Food Contact Notification (FCN) Program allows for industry registration of new food contact materials, with a defined package of supporting safety information (toxicological, chemical, and environmental). After a 120-day time period to raise objections, the packaging materials are automatically legally approved.

However, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has announced a comprehensive national strategy to confront PFAS pollution, and some US States have their own stricter regulations. For example, Washington has banned PFAS in food packaging and California’s Proposition 65 requires warning labels on containers containing BPA due to the chemical’s harm to the female reproductive system.

Some countries are choosing to exercise caution and seek alternatives to these chemicals in food contact materials. BPA is banned in France and PFAS is banned in food packaging in Denmark. Canada is taking steps to ban BPA in baby bottles, although they acknowledge this is a precautionary level, as studies do not indicate exposure levels that cause health effects.

The European Union has no specific legislation and instead, has general legislation that leaves it up to manufacturers to ensure that food contact materials “do not transfer their constituents to food in quantities which could endanger human health” (EU Framework Regulation).

Why is Regulation Difficult?

Lack of Information – Part of the difficulty in banning these substances is that extensive research is required to assess the health and environmental impacts of large numbers of individual chemicals; the chemical class of PFAS alone comprises thousands of chemicals. Therefore, only a few PFAS are banned.

Controversy Over Toxicity Levels – Additionally, U.S. regulations are based on the amount of chemical believed to be ingested as a result of different food packaging, and how toxic this amount is believed to be. However, there is controversy about how much chemical is 1) dangerous to ingest and 2) is ingested by the average American, and some scientists believe the U.S. determinations of toxicity are too narrow.

Scientists propose that PFAS be managed as a chemical class to move towards eliminating their non-essential uses, developing safer alternatives, and developing methods to remove existing PFAS from the environment. (Kwiatkowski et al., 2020).

The EU and other countries are currently compiling research on chemicals in food contact materials intended to support legislation protecting public health. Read more about the European Food Safety Authority’s research efforts.

More Resources

Podcasts

- You Make Me Sick – This episode of the Environmental Defense Fund’s Health podcast talks with Dr. Ami Zota about the presence of food packaging chemicals in people’s urine after eating fast food.

- The Joe Rogan Experience Episode #1638 – This episode with Dr. Shanna Swan discusses research showing declining fertility rates in the U.S. due to chemical exposure.

- Health in a Heartbeat – This UFHealth podcast discusses the dangers of phthalates in plastics.

Books

- Our Daily Poison: From Pesticides to Packaging, How Chemicals Have Contaminated the Food Chain and Are Making Us Sick by Marie-Monique Robin (Kirkus Reviews)

- Accompanying documentary of the same name

- Count Down: How Our Modern World Is Altering Male and Female Reproductive Development, Threatening Sperm Counts, and Imperiling the Future of the Human Race by Shanna H. Swan with Stacey Colino (NYTimes Review).

Databases and Other Helpful Information

- NIEHS-supported Bisphenol A Research Articles – A list of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences studies on BPA

- EPA PFAS Explained Site – EPA site includes information about PFAS, exposure to PFAS, and how to minimize risk.

- FDA Overview of Food Ingredients and Packaging – The FDA website contains information and resources on food packaging.

- EPA Facts and Figures about Waste in the US – This site provides information about what types of packaging materials are recycled or end up in landfills in the U.S.

- Model Toxics in Packaging Legislation for U.S. States – The Toxics in Packaging Clearinghouse (TPCH) maintains the Model Toxics in Packaging Legislation that can be picked up by individual states for implementation of state legislation based on the Model. This model has been used by 19 states to create their own legislation.

- Food Packaging Product Stewardship Considerations – The Institute of Packaging Professionals – Food Safety Alliance for Packaging has developed its own voluntary guidance recommending against several chemicals (e.g. phthalates, BPA, and some PFAS).

Sources

CDC. Phthalates Factsheet. https://www.cdc.gov/biomonitoring/Phthalates_FactSheet.html

ChemTrust. Chemicals in Food Contact Materials. https://chemtrust.org/food-contact-materials/

EPA Press Office. (2021, October 18). Comprehensive National Strategy to Confront PFAS Pollution. https://www.epa.gov/newsreleases/epa-administrator-regan-announces-comprehensive-national-strategy-confront-pfas

Everts, S. (2009, August 31). Chemicals Leach From Packaging. American Chemical Society. https://cen.acs.org/articles/87/i35/Chemicals-Leach-Packaging.html

Groh, K. J., Backhaus, T., Carney-Almroth, B., Geueke, B., Inostroza, P. A., Lennquist, A., … & Muncke, J. (2019). Overview of known plastic packaging-associated chemicals and their hazards. Science of the total environment, 651, 3253-3268. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0048969718338828

Irvine, A. (2018, January 16). A Beginner’s Guide to FDA Food Contact Materials Regulations. FoodSafety Magazine. https://www.food-safety.com/articles/201-a-beginners-guide-to-fda-food-contact-materials-regulations

Kwiatkowski, C. F., Andrews, D. Q., Birnbaum, L. S., Bruton, T. A., DeWitt, J. C., Knappe, D. R., … & Blum, A. (2020). Scientific basis for managing PFAS as a chemical class. Environmental Science & Technology Letters, 7(8), 532-543. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/full/10.1021/acs.estlett.0c00255

Muncke, J. (2013, April 22). Migration. Food Packaging Forum. https://www.foodpackagingforum.org/food-packaging-health/migration

Muncke, J., Andersson, A. M., Backhaus, T., Boucher, J. M., Almroth, B. C., Castillo, A. C., … & Scheringer, M. (2020). Impacts of food contact chemicals on human health: a consensus statement. Environmental Health, 19(1), 1-12. https://ehjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12940-020-0572-5

NIEHS. Bisphenol A (BPA). https://www.niehs.nih.gov/health/topics/agents/sya-bpa/index.cfm

NY State Dept. of Health. Bisphenol A. https://www.health.ny.gov/environmental/chemicals/bisphenol_a/

Rand, A. A., & Mabury, S. A. (2011). Perfluorinated carboxylic acids in directly fluorinated high-density polyethylene material. Environmental science & technology, 45(19), 8053-8059. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/es1043968

Rudel, R. A., Gray, J. M., Engel, C. L., Rawsthorne, T. W., Dodson, R. E., Ackerman, J. M., … & Brody, J. G. (2011). Food packaging and bisphenol A and bis (2-ethyhexyl) phthalate exposure: findings from a dietary intervention. Environmental health perspectives, 119(7), 914-920. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3223004/

Schaider, L. A., Balan, S. A., Blum, A., Andrews, D. Q., Strynar, M. J., Dickinson, M. E., … & Peaslee, G. F. (2017). Fluorinated compounds in US fast-food packaging. Environmental science & technology letters, 4(3), 105-111. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/acs.estlett.6b00435

Silent Spring Institute. Food packaging. https://silentspring.org/project/food-packaging

Susmann, H. P., Schaider, L. A., Rodgers, K. M., & Rudel, R. A. (2019). Dietary habits related to food packaging and population exposure to PFASs. Environmental health perspectives, 127(10), 107003. https://ehp.niehs.nih.gov/doi/10.1289/EHP4092

Toxins in Packaging Clearinghouse. https://toxicsinpackaging.org/

Trasande, L. (2018, July 23). Some food additives raise safety concerns for child health; AAP offers guidance. American Academic of Pediatrics. https://www.aappublications.org/news/2018/07/23/additives072318

Trasande, L., Liu, B., & Bao, W. (2021). Phthalates and attributable mortality: A population-based longitudinal cohort study and cost analysis. Environmental Pollution, 118021. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0269749121016031

US Dept. of Labor. Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Styrene. https://www.osha.gov/styrene

US EPA. Basic Information on PFAS. https://www.epa.gov/pfas/basic-information-pfas

US EPA. Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) in Pesticide Packaging. https://www.epa.gov/pesticides/pfas-packaging

US FDA. Bisphenol A (BPA). https://www.fda.gov/food/food-additives-petitions/bisphenol-bpa

US FDA. Packaging & Food Contact Substances (FCS). https://www.fda.gov/food/food-ingredients-packaging/packaging-food-contact-substances-fcs

US FDA. Phthalates. https://www.fda.gov/cosmetics/cosmetic-ingredients/phthalates

Zimmermann, L., Dierkes, G., Ternes, T. A., Völker, C., & Wagner, M. (2019). Benchmarking the in vitro toxicity and chemical composition of plastic consumer products. Environmental science & technology, 53(19), 11467-11477. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.est.9b02293