Hundreds of pints of spoiled Ben & Jerry’s ice cream awaited their fate in a Williston warehouse this month.

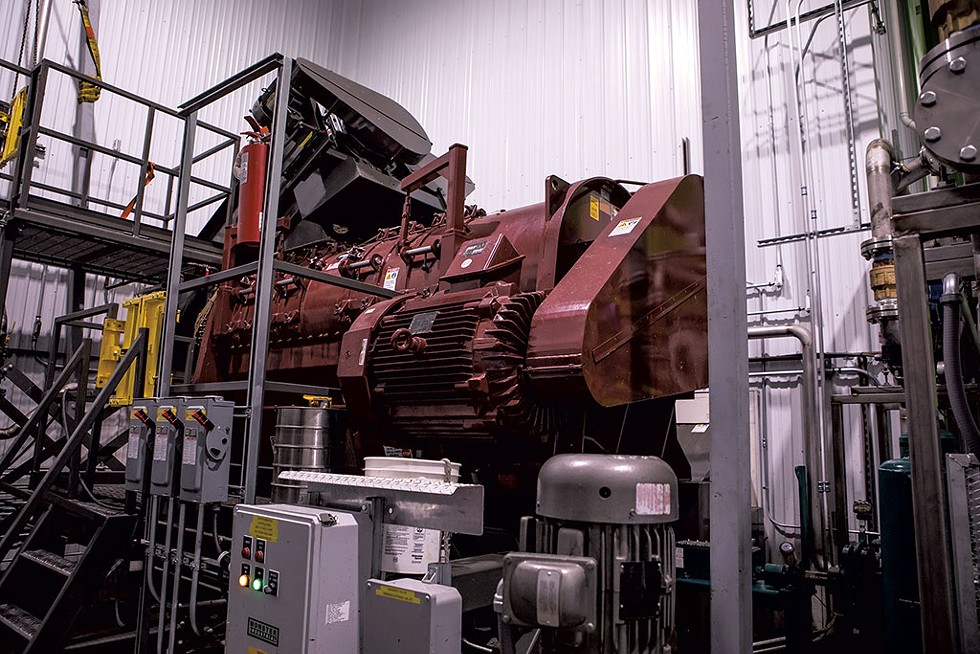

Unfit for sale, the sweet rejects from the company’s factories would be scooped up by a worker driving a payloader and tipped with a crash into a filthy metal hopper. Augers would funnel the mess to a monstrous red machine with powerful spinning paddles that would pummel the pints, breaking down the cardboard and plastic packaging and separating most of it from the sugary slop.

Welcome to Vermont’s first waste depackaging facility, where Americone Dreams go to die.

Casella Waste Systems fired up the $3 million waste-processing plant in January and, with it, a controversy about the new type of food waste it generates.

The facility is designed to tackle the problem of what to do with food waste that is banned from Vermont’s only landfill, in Coventry, but still encased in boxes, plastic bottles and plastic bags.

The new machinery can process thousands of tons a year of food that is thrown away by manufacturers and grocery stores while still in its plastic, metal or paper packaging. Manufacturers such as Ben & Jerry’s often need to discard batches of food and beverages that don’t meet their strict quality-control standards or are past their shelf life. The Williston facility also handles food waste from homes, restaurants, apartment complexes and institutions.

While the process separates out most contaminants, it does not capture them all. That melted Ben & Jerry’s ice cream and other food slop will still contain tiny bits of plastic when it leaves Casella’s separator and is shipped to biogas plants. There, when mixed with other food or farm waste, it will decompose in huge digesters, generating methane that is turned into energy. Some of the plastic — the crucial question is how much — will still be present when the depleted material is spread on Vermont farm fields.

The state’s nearly decade-long drive to steer all organic material — whether leaves raked off lawns, vegetables scraped off dinner plates or stale bread tossed from supermarket shelves — out of the landfill and into animal feed, healthy soil and green energy has made Vermont a leader in food waste recovery. But the solution to one problem — wasting valuable landfill space with food that simply rots — has unintentionally caused another, say critics of the new process.

So far this year, more than 500 tons of material from digesters that accept this depackaged waste have likely been applied to farmland in Vermont, according to data from the state Department of Environmental Conservation.

“It’s foolish to think that we can lace our precious agricultural lands with countless bits of indestructible microplastic and not suffer the health and environmental consequences,” said Paul Burns, executive director of the Vermont Public Interest Research Group.

The impact of plastic in soils is not well understood, but studies show that it can affect soil health, reduce plant vigor, and, if the particles are small enough, be absorbed by plants and end up in food for animals and people.

So far, all that tonnage has gone to just three farms. But state regulators are concerned enough that they’ve instituted what amounts to a moratorium on more farms spreading the waste on fields until they learn more about what’s in it.

Supporters say the Casella depackaging plant is a vital tool in the campaign to recycle more food waste and conserve landfill space. A 2018 study of Vermont’s waste stream estimated that 24 percent of all landfilled waste, or 80,000 tons a year, was organic material that could be put to better use. Of that, 38 percent was discarded still in its packaging.

Surrounding states are adding depackaging capacity, supporters note. Without similar equipment, Vermont’s food and beverage businesses may be forced to haul its packaged waste out of state. Hannaford, for example, trucks expired food from its 15 Vermont supermarkets to a depackaging and biogas power plant outside Bangor, Maine, a six-hour drive from Burlington.

Depackaging food waste can also help extend the life of the Coventry landfill, boost green-energy production and provide farmers with an alternative to synthetic fertilizers.

In April, Cathy Jamieson, manager of the state’s solid waste program, told lawmakers the plain truth: “We need to deal with food waste in packaging if we want to divert these materials.”

Guessing Game

-

Luke Awtry

- From left: Mike Casella, Steven Collier and Anson Tebbetts examining food slurry

When Casella started to search for a depackaging machine several years ago, the company sought the best technology on the market, according to the Williston facility’s general manager, Mike Casella.

The firm certainly has the resources to get the best. Started by two brothers in Rutland, Casella is now a publicly traded company that operates massive waste operations from Maine to Pennsylvania. It dominates waste hauling in Vermont and owns the landfill in Coventry.

Casella ultimately chose the Thor Turbo Separator, which manufacturer Scott Equipment touts as capable of processing 40 tons of organic material per hour and rendering it “99 percent clean.”

“There will always be pieces of plastic, glass, or metal that scoots through our screens,” the company says on its website. “All we can share is that our system is good at keeping it to a bare minimum.”

But 10 months into the new operation, Mike Casella acknowledged that the amount of nonorganic material departing the depackaging operation is little more than guesswork. “It’s definitely less than 5 percent,” he said. He later amended that to 1 percent and then “less than half a percent, or even less.”

“To be honest, we don’t know,” he said finally.

The more the company can learn about what contaminants get through the process, he said, the more work it can do with customers to keep them out of the food waste.

One reason for the uncertainty is the great variability in the material being run through the Thor, so named to highlight the power of its spinning hammers.

Discarded cans of beer from local brewers such as Frost Beer Works, Zero Gravity Craft Brewery and Fiddlehead Brewing pose virtually no risk of contamination. Workers presort the material to remove and recycle any plastic carriers and cardboard packaging, leaving just the aluminum cans to be smashed open. The cans themselves are compacted into bales and recycled.

Other items aren’t quite so simple. In the case of single-serve coffee K-Cups, the Thor’s smashing action must separate the coffee grounds from the cardboard boxes they come in, the white plastic container cups, small plastic internal filters and foil tops.

Most problematic are the tons of food scraps from green bins picked up from restaurants, schools, hospitals, hotels, apartment buildings and homes. On a recent visit to the Williston facility, Mike Casella waded into a concrete bunker full of stinking waste on its way to the Thor to find it polluted with non-compostable drink cups, straws, plastic bags and ketchup packets. He tugged on a bit of fabric and pulled out a slimy shirt.

The volume of these postconsumer food scraps — and the non-compostable waste in the mix — has increased dramatically since last year. That’s because on July 1, 2020, the state law that bans food waste from being discarded as trash took full effect.

The largest compost operation in the state, the Chittenden Solid Waste District‘s Green Mountain Compost, is having such difficulty keeping its compost clean that it is instituting new rules on January 1. Compostable foodware such as plates and utensils will no longer be accepted, because sorting out what is actually compostable and what is plastic has become too labor-intensive, CSWD officials say.

Casella previously hauled most of its organic material to Green Mountain Compost, but those shipments have dropped off sharply since the depackaging facility came online. The 373 tons or so of food scraps per month that Casella was taking to CSWD started falling in January, decreased steadily to 47 tons by June and eventually flatlined to zero, according to CSWD data.

Now Casella is running those food scraps through the Thor’s screens to sift out contaminants, mixing them into a slurry and sending it off to boost energy production. Tanker trucks haul the nutrient-rich goop to digesters, where microorganisms break it down in oxygen-free environments, releasing methane that’s burned for heat or to generate electricity. Vermont farms have been using digesters to make power from cow manure for several decades, and the practice is growing.

It’s the depleted food waste that emerges from digesters that is the cause of current concern.

PurposeEnergy of Windham, N.H., helped build the nation’s first brewery waste-to-electricity plant at the former Magic Hat Brewing in South Burlington in 2010. The company now uses it to blend the depackaged food from Casella with watery waste from multiple brewers, distillers and food manufacturers. PurposeEnergy has three more digesters in development in Vermont.

Earlier this year, Vanguard Renewables of Wellesley, Mass., opened the largest digester in New England at the Goodrich Family Farm in Salisbury. Much of the gas produced is sold to Middlebury College to reduce its fossil-fuel use.

About 80 percent of the food slurry generated at Casella’s depackaging plant is delivered to digesters in South Burlington and Salisbury, Casella said. It’s also been trucked to a third digester at Gebbie’s Maplehurst Farm in Greensboro.

Tiny Shards

The University of Vermont is studying Casella’s process to determine exactly what contaminants aren’t filtered from the organic waste and their potential impact on the environment. Casella and UVM’s Gund Institute for Environment contributed a combined $260,000 toward the research.

Under the direction of Eric Roy, interim director of the college’s environmental sciences program, two graduate students are tackling the issue from different angles. Sarah Hobson, who is pursuing a master’s degree in environmental science, is reviewing the published literature on depackaged food waste, composting and plastics contamination to understand the impact of plastic in food waste.

Kate Porterfield is a doctoral candidate in the engineering and math department who is studying biogas production rates. She’s also looking at microplastics contamination. “Microplastics” generally refers to tiny fragments of plastic, five millimeters or smaller.

To discover how much biogas different types of food waste produce, Porterfield takes samples from the depackaging equipment, runs them through a mini-digester in the UVM lab and analyzes the gas produced. She then uses a biological process to break down the waste further to help her more easily find, count and categorize the tiny bits of plastic left behind.

On the counter in her lab at UVM, Porterfield showed off dozens of tiny glass vials, each containing bits of what she presumes to be plastic, labeled by their size and the dates they were collected. Additional tests are needed to confirm that the shards are, in fact, plastic, but to the untrained eye the samples look unnatural. One bore a distinct pattern of tiny green dots in neat rows on a yellow background, leaving no doubt that the material was man-made — likely a plastic film used in food packaging.

Preliminary results indicate that the amount of microplastics in the Casella waste is comparable to what’s been found during studies of compost and food waste conducted elsewhere, Roy said. Researchers typically count the number of microplastic particles per kilogram. Existing studies vary widely, and most have found between 20 and 2,800 particles per kilogram, Roy said. Additional testing on a wider variety of samples from Casella is still needed.

“We have more work to do to put this information into a better context,” Roy said. He expects to publish the team’s work in early 2022.

Quantifying the amount of plastic headed to farm fields is one thing; understanding what risks, if any, it poses to human health and the environment is very different, Roy said.

Some studies indicate that microplastics may damage soil and plant health, Roy said during a recent webinar describing the research. They may inhibit plant and root growth and cause lower germination rates in seeds. Some suggest that microplastics could lower soil’s capacity to hold water.

But other studies indicate that microplastics may improve soil aeration and drainage, he said.

Plastic makes its way into agricultural soils from various sources: as mulch used to deter weed growth, irrigation systems, farm equipment and even litter, Roy said.

That may make it challenging for researchers to pinpoint the sources of microplastics already in the landscape, let alone comprehend the impact of new ones.

“We do need some more basic understanding of what’s out there already and how microplastics may be problematic,” Roy said.

Deb Neher, a professor in the UVM Department of Plant and Soil Science, told Seven Days that a growing a body of data suggests that microplastics in soil are an increasing problem. She expects that UVM’s research will provide important data and insight into how big a problem the issue is in Vermont.

Because plastics don’t break down easily, they accumulate in the soil and the organisms that live there.

Just like aquatic creatures are harmed when they mistake microplastics for food, creatures such as earthworms ingest them and effectively starve because they’re eating material with no nutritional value, she said, noting: “The empirical evidence is mounting of detrimental impacts of microplastics to soil food webs.”

Urging Caution

The depackaging process “has the capacity, if not well implemented, to cause immense harm,” Sen. Chris Bray (D-Addison), chair of the Natural Resources and Energy Committee, told Seven Days. Lawmakers are considering whether additional regulation is necessary.

The state failed to protect residents for years from the health threats posed by per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS, Bray said, and Vermonters deserve better. The so-called “forever chemicals” contaminated the groundwater at the Vermont Air National Guard base, as well as hundreds of private wells near a former Teflon coating plant in the Bennington area.

“Let’s not shoot ourselves in the foot again,” Bray said. “Let’s not poison ourselves and then be stuck dealing with the damage.”

That message appears to be getting through to regulators. Agency of Agriculture, Food and Markets officials have informed Casella that it can continue current operations, but the agency will not approve spreading food waste on additional farms until the issue has been further studied.

Cary Giguere, director of public health and resource management for the agriculture agency, said the pause was needed to give the state time to better understand what is effectively a new, unregulated waste stream.

“This is one of the unintended consequences of the Universal Recycling Law that warrants further examination,” Giguere said, referring to the 2012 legislation that phased out dumping food waste in landfills over several years.

If tiny bits of plastic are seeding farmers’ fields and running off into surrounding waterways, the public is likely to blame farmers, Giguere said. As a result, the agency has informed farmers who have been accepting Casella’s material that more study is needed.

“This falls along the lines of: What we don’t know is of more concern at this point than what we do know,” Giguere said.

Officials from the Department of Environmental Conservation and Agency of Agriculture are developing a sampling program to help determine the extent of the problem.

If the state opts to undertake an extensive soil testing program, it may look for more than microplastics, DEC Commissioner Peter Walke said. Heavy metals and PFAS, which have been linked to the land application of biosolids from wastewater treatment plants, may also merit a closer look.

“If we’re going to do the work, it probably behooves us to take as broad a look as we can,” Walke said.

Before touring the depackaging plant, Walke said, he had assumed that the machinery was “shredding” the pints. But he learned that the hammering process causes the same result as, say, what happens when an ice cream tub is dropped and spills its contents.

“If I scooped that up, I would not have any problem putting that down the drain or in my compost,” he said.

Agriculture Secretary Anson Tebbetts also toured the depackaging plant earlier this month and came away sounding impressed.

“It’s amazing technology, what is occurring here,” he said. “We have this tremendous amount of waste, and we can somehow convert it into something that could be useful, as opposed to throwing it into a landfill.”

He pointed to a ketchup packet caught in the Thor’s screens as evidence that waste is captured, but he acknowledged that proved little when it comes to microplastics.

“I think people are trying to figure out how much of it is making its way into the slurry,” Tebbetts said. “That’s what we’re trying to figure out. Is it 1 percent? Two percent? Ten percent?” He echoed Mike Casella: “I don’t know.”

Farmers Fret

The agriculture agency’s decision to put farmers on notice has some of them worried.

Laura DiPietro, the agency’s deputy director of agricultural resource management, said she called the three farmers involved to provide them with information. Farmers have taken clean bulk food waste from manufacturers for years, but ag officials wanted to make certain they understood that the depackaged material is different, DiPietro said.

Peter Gebbie in Greensboro started receiving shipments of waste from the depackaging operation over the summer. It went into a digester and was mixed with manure from his 250 beef cattle; the food waste, particularly when nutrient rich, increased the production of gas. That, in turn, generated electricity that he sold to utilities. The spent material flowed to his manure pit and was spread on his fields.

The news that he might have inadvertently distributed plastics on his land was troubling, he said. “I wouldn’t want that any more than most people would,” Gebbie said.

If Casella can show that it can keep plastic out of the waste, Gebbie said, he’d probably take the material again, although he might not get the chance. A fire destroyed his digester in September, and he doesn’t know whether he’ll be able to rebuild.

St. Albans dairy farmer Jeff Boissoneault also accepted some of Casella’s organic waste: 86 tons of leftovers from the digester that PurposeEnergy built for Magic Hat. He is waiting for additional information before deciding whether to take more material, said his son Cody.

Eric Fitch, founder and CEO of PurposeEnergy, said the information that the agriculture agency gave Boissoneault was “inaccurate and completely unrelated to our process or the materials we receive.”

“It is a very unfortunate situation,” he wrote in an email. He did not elaborate.

But in an email to DiPietro, he wrote that the amount of potential contamination was minuscule, given how light the packaging was compared to the food waste and the screens designed to remove it. He estimated that, even if packaging evaded all screens, it might represent 0.001 percent contamination.

“Researchers at UVM are studying these materials, and it may be prudent to wait for their results so that accurate information can be shared with the farming community,” he wrote.

All In on Biogas

Vanguard Renewables, the developer of the huge digester in Salisbury that is fueling Middlebury College, has made a big bet on biogas not only in Vermont but also around the nation. It has six facilities in operation, five in Massachusetts and one in Vermont, and 10 others in development, Ray Duer, vice president of sales, said in a recent webinar. Biogas is crucial to addressing climate change, he said, and Vanguard’s “aggressive” growth strategy envisions installing 60 digesters across the country in four years.

While few farms have spread material from Casella’s depackaging facility so far, industrial depackaging is in its infancy. More and more food manufacturers are committing to zero-waste goals, Mike Casella said. The Williston facility could handle much more material than it currently does, he added.

In April, Vanguard’s founder, John Hanselman, told lawmakers that Vermont should eventually have multiple depackaging operations. CSWD leaders considered partnering with Vanguard on a depackaging operation of its own, but Casella beat the waste district to the punch.

Asked about microplastic contamination, Hanselman offered general reassurances to lawmakers that plastics were screened out before being spread on Goodrich Family Farm’s fields, which are located along Otter Creek.

“I was less than satisfied with that response,” Rep. Kari Dolan (D-Waitsfield) told Seven Days.

Dolan said the issue is similar to the environmental risk once posed by microbeads, tiny plastic particles used as abrasives in skin care products, soaps and toothpastes. When flushed down the drain, the beads are so small that they pass through wastewater treatment system filters and into waterways, where they can accumulate in aquatic organisms. Vermont began the process of barring microbeads in 2015, before the federal government passed a national ban.

Just as they do in oceans, plastics break down in soil into smaller and smaller pieces. That’s why having additional details about the type of waste screening being used is so important, Dolan said.

Hanselman declined to be interviewed by Seven Days but offered a written statement.

“We recognize that plastic contamination is endemic in all forms of food recycling and utilization, whether composting or animal feed,” he wrote. “We have gone to extra lengths at our anaerobic digester facilities by adding a secondary screening process to remove as much of the residual plastic as possible prior to any land application.”

UVM’s Roy said researchers have not yet been able to test the spent material going onto the Goodrich farmland.

The danger of microplastic contamination is one that composters and others envisioned when the Universal Recycling Law was written, said Tom Gilbert, co-owner of Black Dirt Farm, a compost operation in Stannard.

For that reason, the law contained unambiguous requirements that organic material be separated from contaminants such as plastic “at the point of generation,” which Gilbert has argued is the supermarket. When that requirement became inconvenient, state waste regulators did “an end run” around the law to permit the depackaging facility, he said.

Jamieson, the state’s solid waste manager, responded to this charge in April, telling lawmakers that the language in the law was more of a guide and that mandating businesses to separate food waste from packaging in all situations was impractical and unenforceable.

The legal debate aside, Gilbert said unregulated use of depackaging facilities certainly violates the spirit of the recycling law. The law identifies compost as a higher and better use for organic waste than energy production. While there may be a role for depackaging facilities, the scale of Casella’s diversion of food scraps from compost to biogas shows that “the state is backsliding” on its commitment to those priorities, he said.

It also sends mixed messages. As Gilbert put it, why should Vermonters be told that they have to separate their food waste from packaging, but supermarkets can toss stale cookies still in their plastic containers into a bin and ship it to Maine or Williston for a big machine to sort out?

And if that separation process leads to polluted farmland, “that would be criminal,” Gilbert said.

“Local food is a major solution to climate change,” he said. “You fuck up our soil, you fuck up our ability to pull on that lever.”