Bob Powell had spent more than a decade in the energy industry when he turned his attention to the problem of plastic waste. “I’m very passionate about the environment,” he says. To him, the accumulating scourge of irresponsibly discarded plastic ranks high on the list of environmental issues, “right behind global warming and drought.” In 2014, he found what he considers a solution: a suite of technologies that uses chemicals and heat to turn plastic into oil to manufacture more plastic.

In the years since, Powell founded a “plastics renewal” company, Brightmark, Inc., whose first plant, currently in its start-up phase, has processed 2,000 tons of waste plastic at its Circularity Center in Ashley, Indiana. Using an “advanced plastics recycling” technique called pyrolysis, post-consumer plastics delivered to the Brightmark plant are subjected to intense heat in an oxygen-starved environment until their molecules shake apart, yielding a type of oil similar to plastic’s petroleum feedstock, along with some waste byproducts. Ideally, Powell says, Brightmark will sell the oil to produce new plastic, promoting true circularity in the manufacturing supply chain.

Around the world, companies are drawing up plans for pyrolysis plants, promising relief from the crushing problem of plastic pollution. Small startups and demonstration projects are joining with larger companies, including petroleum and chemical giants. Chevron Phillips was recently awarded a patent for its proprietary pyrolysis process, and ExxonMobil announced in March it was considering opening pyrolysis plants in Baton Rouge, Louisiana; Beaumont, Texas; and Joliet, Illinois. ExxonMobil already operates a pyrolysis facility in Baytown, Texas, which the company claims will recycle 500,000 tons of plastic waste annually by 2026.

“There’s a lack of transparency about how much plastic they’re recycling” and what the end product will be used for, a critic says.

Globally, the market for advanced recycling technologies is projected to exceed $9 billion by 2031, up from $270 million in 2022, according to a report from Research and Markets, an industry analysis firm. That’s a 32 percent increase every one of those nine years.

Proponents of pyrolysis say it will keep plastic out of landfills, incinerators, and waterways, prevent it from choking marine life, and keep its toxic components from leaching into soil and contaminating water and air. The American Chemistry Council says that “advanced recycling reduces greenhouse gas emissions 43 percent relative to waste-to-energy incineration of plastic films made from virgin resources.”

The technology can handle the plastics that can’t be mechanically melted and remolded — those stamped with the numbers three through seven, including certain plastic films, juice pouches, and polystyrene foam take-out boxes. The pyrolysis vessel itself emits nothing — there’s no oxygen, so no combustion — although heating it with fossil fuel releases the usual greenhouse gases and other pollutants.

Opponents argue, however, that pyrolysis practitioners aren’t being entirely honest about their manufacturing outcomes. “There’s a real lack of transparency about how much plastic they’re recycling” and what their end product — pyrolysis oil — will actually be used for, says Veena Singla, a senior scientist at the Natural Resources Defense Council.

Some companies, such as LG Chem in South Korea, do have verifiable plans to process plastic items into useful hard goods. The company has partnered with the marine-waste disposal company NETSPA to turn fishnets and buoys into a substance called “aerogel,” a superlight insulation; its pyrolysis plant is scheduled to be up and running near Seoul by 2024.

But what pyrolysis mostly does, says Singla, is make oil to be refined and then sold as fuel. An analysis by the Minderoo Foundation, an Australia-based philanthropic organization focused on the environment, calculated that of the roughly 2 million tons of advanced recycling capacity scheduled to come online over the next five years, less than half a million tons of this material will actually be recycled back into plastic goods. The rest of the output is destined to power airplanes, trucks, and other heavy transportation.

Depending on the type of plastic that enters a pyrolysis vessel and the current price of oil, turning plastics into fuel might be profitable. What it’s not, says Singla, is recycling. “The benefit of recycling comes when you return materials into the production cycle, which reduces the demand for virgin resources.” That’s what the traditional, mechanical recycling of simple polyethylene terephthalate (PETE) and high-density polyethylene (HDPE) plastic does. Making plastic goods with recycled content generates 30 to 40 percent fewer greenhouse gas emissions than making plastics from virgin resources. “Now if you’re taking plastic and burning it as fuel,” Singla says, “it’s not feeding back into plastic production. And so to keep making [new] plastic, you have to keep extracting fossil fuel.”

The data from one study suggests creating pyrolysis oil from used plastic is worse for the climate than extracting crude from the ground.

Powell says his aim is 100 percent circularity, plastic to plastic, “and we’re going to be relentless in that pursuit.” But while the market matures and prices for recycled plastic drop, he admits that as “an interim step” some pyrolysis oil could be sold as fuel. “In some emerging economy nations, there may not be a viable way to use the liquids as a feedstock to make plastics,” he says. They may be too far from manufacturing facilities for plastic manufacturing to make sense, for instance. But Powell insists even this outcome is better than leaving the 90 percent of post-consumer plastic that isn’t recycled to accumulate in the environment. “I’m sure you’ve seen the videos of places where there are just rivers of plastics flowing. If we were to pull those plastics out and turn them into fuel, is that a better environmental outcome?”

“Yes it is,” he answers himself. “You’d better believe it.”

Turning plastic into fuel would obviously help keep the petroleum-based polymer industry afloat: To some observers, that’s the point of advanced chemical recycling. “The fossil gas industry is seeking to use plastics as a way to expand their production, even as they are contributing enormously to climate chaos,” says Senator Jeff Merkley of Oregon, one of 47 U.S. Senators, all Democrats, who signed a letter objecting to the EPA’s 2021 proposal to regulate pyrolysis and gasification as manufacturing instead of incineration, which is more tightly regulated. Merkley has also questioned the EPA’s inclusion of plastic-based fuel as a “waste-based” fuel under the Renewable Fuel Standard, a federal program that requires transportation fuel sold in the U.S. to contain a varying percentage of renewable fuels to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

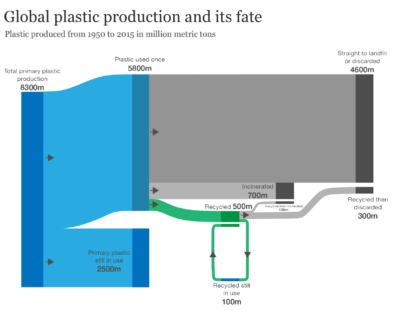

The fate of plastic produced globally from 1950 to 2015 in million metric tons.

Our World in Data / adapted by Yale Environment 360

Fuel made from plastic does not meet the basic criteria for biofuels or renewable fuels, says Taylor Uekert, a researcher at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL), in Golden, Colorado, and lead author of a study on plastics recycling methods. “Plastic is not an infinitely renewable resource,” Uekert says. Nor is plastic-based fuel a win for the climate. “If you’re turning plastic back into oil for fuel,” she says, “you need to be comparing it to the environmental impacts of creating that fuel from fossil sources.”

NREL researchers have begun collecting data from patent applications that compare the energy it takes to produce pyrolysis oil with the energy that burning that oil can generate. So far, the data suggests that creating pyrolysis oil from used plastic, including the energy required to superheat the vessel, is worse for the climate than extracting new crude from the ground.

“In general, you’re getting higher greenhouse gas emissions from pyrolysis than you would from conventional drilling,” Uekert says. And you can’t just turn around and add pure pyrolysis oil to your gas tank. It needs to be refined. That refining process is where the most serious consequence of plastic-to-fuel comes in, impacting the people who live near refineries — most of them Black, Brown, or low-income — with another set of toxic emissions.

A Mississippi citizens’ group is suing the EPA for approving plastic-based fuel production at a Chevron refinery.

Reporting in ProPublica uncovered data from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency that showed long-term exposure to emissions associated with the production of jet fuel from plastic-based oil carries a one-in-four lifetime cancer risk. “That kind of risk is obscene,” Linda Birnbaum, former head of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, told ProPublica. Nevertheless, the EPA has authorized production of this “new chemical” at a Chevron refinery in Pascagoula, Mississippi, without revealing the proprietary substance’s name.

Chevron’s refinery isn’t the only facility turning pyrolysis oil into transportation fuels, notes Kathleen O’Brien, a senior attorney with the Toxic Exposure and Health Program at the environmental law firm Earthjustice. “We’re aware of other facilities in other parts of the country that have also indicated that they’re refining or producing fuel products from pyrolysis oils,” she says. But it’s difficult to understand the scope of the problem, or even which particular communities are at risk, “because of the profound lack of transparency from the EPA in the process for approving these new chemicals.” Earthjustice is currently representing a Mississippi citizens’ group suing the EPA for approving, under the Toxic Substances Control Act, the Chevron refinery’s plastic-based fuel production. Says O’Brien, “We intend to challenge the EPA’s lack of transparency as a legal violation in that case.”

Plastic waste in Ballona Creek in Culver City, California.

Citizen of the Planet / UIG via Getty Images

Alexis Goldsmith, an organizer with the nonprofit Beyond Plastics, says that pyrolysis and its analogs, which she calls “false recycling,” have another drawback: “They take away political will from waste reduction,” she says, potentially dissuading lawmakers from passing plastic bag bans and other legislation that might reduce the amount of plastic in circulation. Instead, some state governments are welcoming pyrolysis and gasification of plastic as a solution to plastic waste, obviating the need to reduce polymer use in the consumer and business sectors. As of this April, 24 states, including Indiana, where Brightmark’s Circularity Center is located, have passed laws classifying pyrolysis and gasification as manufacturing instead of incineration or solid waste disposal, clearing the way for the plants to operate under lighter regulation and sometimes with government incentives for job creation.

Goldsmith thinks it’s the wrong idea altogether. “We can’t recycle our way out of the plastic-waste crisis,” she says, either by mechanical or chemical means. “We need to require the world’s biggest plastic polluters to reduce the amount of plastic that they’re pumping into the market in the first place.”

So what to do with the hundreds of millions of tons of polymers already circulating in the environment, consumer sector, and waste stream? “Contain it,” she says, “just like we do with nuclear waste. Better to contain it in a landfill than burn it.”

Walking along the Allegheny River with scenic views of the city’s iconic yellow bridges, the group learned about how pollution from the steel industry was once so bad that Pittsburgh was nicknamed “hell with the lid off.”Credit: Kristina Marusic for Environmental Health News

Walking along the Allegheny River with scenic views of the city’s iconic yellow bridges, the group learned about how pollution from the steel industry was once so bad that Pittsburgh was nicknamed “hell with the lid off.”Credit: Kristina Marusic for Environmental Health News